Abstract

This chapter describes the properties of paramyxoviruses and pneumoviruses, and features of the diseases they cause in animals.

Keywords: Paramyxovirus, pneumovirus, morbillivirus, henipavirus, avulavirus, Paramyxoviridae

The families Paramyxoviridae and Pneumoviridae are included in the order Mononegavirales, along with the families Rhabdoviridae, Filoviridae, Nyamiviridae, and Bornaviridae. This order was established to bring together viruses with distant, ancient phylogenetic relationships (Fig. 17.1 ) that are also reflected in similarities in their gene order and strategies of gene expression and replication. All these viruses are enveloped, have prominent envelope glycoprotein spikes, and have genomes consisting of a single molecule of negative-sense, single-stranded RNA. The features that differentiate the individual families of the order include genome size, nucleocapsid structure, site of genome replication and transcription, manner and extent of messenger RNA (mRNA) processing, virion size and morphology, tissue specificity, host range, and pathogenic potential in their respective hosts (Table 17.1 ).

Figure 17.1.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of members of the order Mononegavirales. The tree was constructed using the sequences of the conserved domain III of the RNA polymerase. ABV, avian borna virus; AMPV, avian metapneumovirus; APMV2, avian paramyxovirus 2; APMV3, avian paramyxovirus 3; APMV4, avian paramyxovirus 4; APMV6, avian paramyxovirus 6; AsaPV, atlantic salmon paramyxovirus; BDV, Borna disease virus; BEFV, bovine ephemeral fever virus; BeiPV, Beilong paramyxovirus; CDV, canine distemper virus; FdlPV, Fer-de-Lance virus; HeV, Hendra virus; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; hRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; IHNV, infectious hemorrhagic necrosis virus; JPV, J virus; LNYV, lettuce necrotic yellows virus; MARV, Marburg virus; MenPV, Menangle virus; MeV, measles virus; MMV, maize mosaic virus; MuV, mumps virus; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NiV, Nipah virus; PIV3, parainfluenza virus 3; PtldV, Portland virus; PVM, pneumonia virus of mice; RabV, rabies virus; SeV, Sendai virus; SV5, simian virus 5; SYNV, Sonchus yellow net virus; TioPV, Tioman virus; TlmPV, Tailam virus; TupPV, Tupaia paramyxovirus; VHSV, viral hemorrhagic septicaemia virus; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; ZEBOV, Zaire ebolavirus.

Adapted by V. von Messling from King, A.M.Q., Lefkowitz, E., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B. (Eds.), 2011. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 657. © Elsevier (2012), with permission.

Table 17.1.

Distinguishing Characteristics of Four Families of the Order Mononegavirales

| Characteristic | Family Paramyxoviridae | Family Rhabdoviridaea | Family Filoviridae | Family Bornaviridae |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (kb) | 15–19 | 11–15 | 19 | 9 |

| Virion morphology | Pleomorphic | Bullet-shaped | Filamentous | Spherical |

| Site of replication | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Nucleus |

| Mode of transcription | Polar with nonoverlapping signals (except pneumoviruses) and stepwise attenuation | Polar with nonoverlapping signals and stepwise attenuation | Polar with nonoverlapping signals and stepwise attenuation | Complex with mRNA splicing and overlapping start/stop signals |

| Host range | Vertebrates | Vertebrates, insects, and plants | Humans, nonhuman primates, pigs, and bats | Horses, sheep, cats, birds, (humans?) shrews and possibly other small mammals |

| Pathogenic potential | Mainly respiratory disease | Mild febrile to fatal neurological disease | Hemorrhagic fever | Immune-mediated neurological disease in mammals |

| Proventricular dilation syndrome in birds |

Vertebrate virus members.

The family Paramyxoviridae includes pathogens that cause some of the most devastating human and veterinary diseases. In particular, rinderpest, canine distemper, Newcastle disease, measles, and mumps viruses have arguably resulted in more morbidity and mortality than any other single group of related viruses. The use of vaccines in both humans and, often in combination with depopulation and movement restrictions, in animals, has dramatically reduced the impact of these diseases, and even resulted in the eradication of rinderpest virus in 2011. Other viruses in this family also cause disease in a wide variety of mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles—including, amongst many examples: respiratory syncytial viruses in cattle, sheep, goats, and wildlife; Sendai virus (murine parainfluenza virus 1) in rodents; avian rhinotracheitis virus (avian metapneumovirus) in turkeys and chickens; phocine morbillivirus in seals; ophidian paramyxoviruses, including Fer-de-Lance virus in snakes; and aquatic paramyxoviruses in salmonid fish. In addition, paramyxoviruses of the genus Henipavirus, which naturally infect various species of bats but cause high mortality rates in infected humans and animals, are emerging pathogens of great public health concern. As wildlife species come more in contact with humans and domesticated animals through changes in habitat, the opportunities increase for cross-species infections by these and additional, as yet unidentified, paramyxoviruses.

The history of paramyxoviruses includes multiple incorrect reports that complicate their taxonomic classification, and confuses assessment of their true ability to cause interspecies infections. Specifically, interpretation of the results of previous sero-surveys was frequently complicated by the considerable cross-reactivity that occurred as a result of inapparent contamination of the test antigens, as well as the stimulation of heterotypic antibodies after infection of animals with individual viruses. Failure to recognize these limitations led to erroneous conclusions, such as a putative link between parainfluenza virus 3 infection and abortion in cattle or respiratory disease in horses.

Properties of PARAMYXOVIRUSES AND PNEUMOVIRUSES

Classification

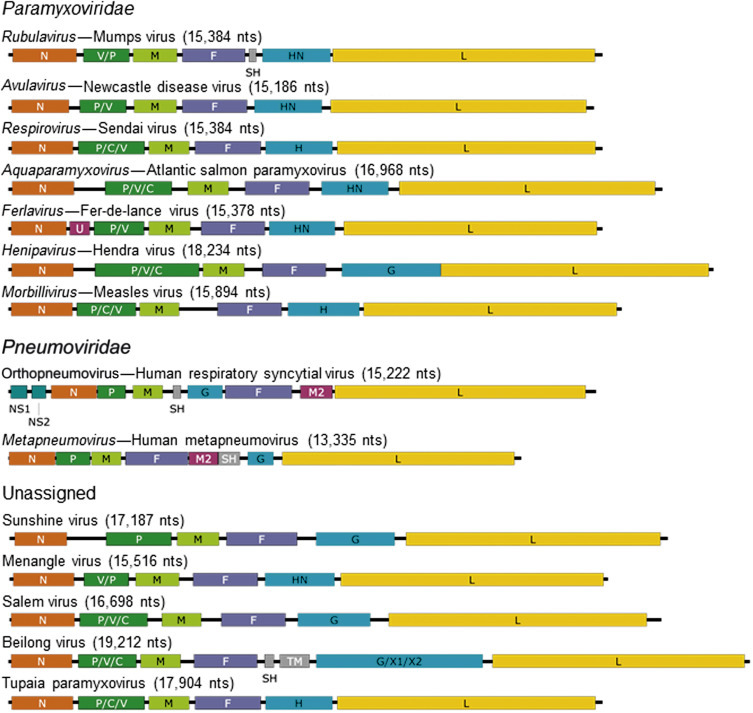

The family Paramyxoviridae contains the genera Aquaparamyxovirus, Avulavirus, Ferlavirus, Heniparvirus, Morbillivirus, Respirovirus and Rubulavirus; the family Pneumoviridae contains the genera Orthopneumovirus and Metapneumovirus (Fig. 17.2 ). The families continues to expand rapidly as new viruses are discovered in wild animal populations, with a growing list of relatively uncharacterized (and currently unclassified) paramyxoviruses from rodents, bats, reptiles, and fish. The list of members and number of genera in the family Paramyxoviridae is certain to grow as the “virome” of more wildlife species is analyzed.

Figure 17.2.

Phylogenetic relationships among the L protein sequences of member viruses of the families Paramyxoviridae and Pneumoviridae.

Adapted by V. von Messling from King, A.M.Q., Lefkowitz, E., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B. (Eds.), 2011. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 684. Copyright © Elsevier (2012), with permission.

The nomenclature of viruses within the family Paramyxoviridae is confusing and fraught with inconsistencies, as individual viruses have been named according to their species of origin (eg, porcine rubulavirus, avian paramyxoviruses 2–12), geographic sites of discovery (eg, Sendai, Hendra, and Newcastle disease viruses), antigenic relationships (eg, human parainfluenza viruses 1–5), or given names related to the diseases that they produce in affected animals or humans (eg, canine distemper, rinderpest, measles, and mumps viruses). Indeed, it appears that many members of this family represent related lineages of viruses that are enzootic in one principal host species but carry the inherent potential to cross over to another species (so-called “species-jumping”). Notably, some of the “chiropteran paramyxoviruses” detected in different bat species are closely related to recognized members of the families Paramyxoviridae and Pneumoviridae, including viruses in the genera Henipavirus, Morbillivirus, Metapnemovirus, Orthopneumovirus, Respirovirus, and Rubulavirus, suggesting that bats may be ancestral hosts of several pathogenic paramyxoviruses of humans and other animals. The identification of a morbillivirus in vampire bats lends credence to the speculation that canine distemper virus was brought to Europe in the 1700s from South America. Rodents may serve a similar role as reservoirs of paramyxoviruses.

The organization of member viruses of the families into genera based on their genome sequence and organization is reflected typically by biological properties that are common to member viruses of each genus, thus taxonomic organization will be retained in this chapter.

Virion Properties

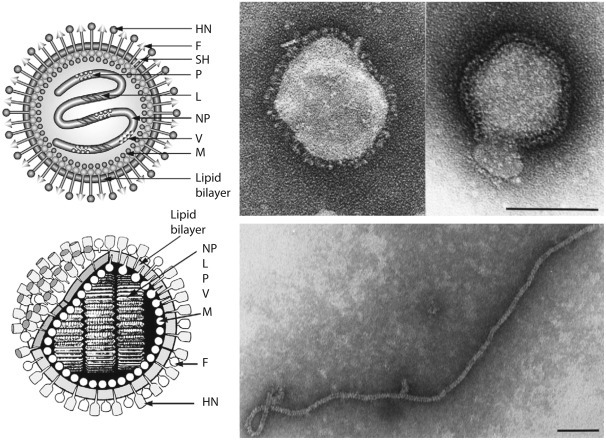

Paramyxovirus virions are pleomorphic, 150–350 nm in diameter (Fig. 17.3 ), and can present as spherical or filamentous particles. Virions are enveloped, covered with large glycoprotein spikes (8–14 nm in length), and contain a “herringbone-shaped” helically symmetrical nucleocapsid, approximately 1 μm in length and 18 nm (Paramyxoviridae) or 13–14 nm (Pneumoviridae) in diameter. The genome consists of a single linear molecule of negative-sense, single-stranded RNA, 13–19 kb in size. The RNA does not contain a 5′ cap and is not polyadenylated at the 3′ end, but does have functional 5′ and 3′ noncoding elements. With the exception of members of the Pneumoviridae, the genomic size follows the “rule of six”—that is, the number of nucleotides is a multiple of six, which appears to be a function of the binding properties of the nucleocapsid (N) protein to the RNA molecule. There are 6–10 genes separated by conserved noncoding sequences that contain termination, polyadenylation, and initiation signals for the transcribed mRNAs (Fig. 17.4 ). The genomes of viruses in the family Paramyxoviridae encode 9–12 proteins through the presence of overlapping reading frames within the phosphoprotein (P) locus, whereas those in the family Pneumoviridae encode only 8–10 proteins. Most of the gene products are present in virions either associated with the lipid envelope or complexed with the virion RNA. The P and polymerase (L) proteins, which form the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, are associated with the N protein-encapsidated viral RNA. This ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is surrounded by the viral envelope consisting of an unglycosylated matrix protein (M), and two glycosylated envelope proteins—a fusion protein (F) and an attachment protein, the latter being a hemagglutinin (H), a hemagglutinin–neuraminidase (HN), or a glycoprotein G that has neither hemagglutinating nor neuraminidase activities. Variably conserved proteins include nonstructural proteins (C, NS1, NS2), a cysteine-rich protein (V) that binds zinc, a small integral membrane protein (SH), and transcription factors M2–1 and M2–2.

Figure 17.3.

(Right) Negative contrast electron micrographs of intact simian virus-5 (SV-5) particles (genus Rubulavirus) (Top) and the SV-5 nucleocapsid after detergent lysis of virions (Bottom) Courtesy of G.P. Leser and R.A. Lamb. The bars represent 100 nm. (Left top and bottom) Schematic diagrams of SV-5 particles in cross section (N) (formerly NP), nucleocapsid; P, phosphoprotein; L, large polymerase protein; V, cysteine-rich protein that shares its N-terminus with P sequence and for SV-5 is found in virions; M, matrix or membrane protein; F, fusion protein; NH, hemagglutinin–neuraminidase; SH, small hydrophobic protein.

Adapted from Kingsbury, D.W., 1990. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields, B.N., Knipe, D.M. (Eds.), Virology, second ed. Raven Press, New York, NY; Scheid, H., 1987. Animal Virus Structure (M.V. Nermut, A.C. Steven, Eds.). Elsevier, Amsterdam with permission. From King, A.M.Q., Lefkowitz, E., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B. (Eds.), 2011. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 655. Copyright © Elsevier (2012), with permission.

Figure 17.4.

Maps of genomic RNAs (3′–5′) of viruses belonging to the family Paramyxoviridae and Pnuemoviridae along with a group of five unassigned viruses. Each box represents a separately encoded mRNA; multiple distinct ORFs within a single mRNA are indicated by slashes. Numbers indicate nucleotide length of the genomic RNA. Protein letter codes are as in Fig. 17.3.

Adapted from King, A.M.Q., Lefkowitz, E., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B. (Eds.), 2011. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA, p. 675. Copyright © Elsevier (2012), with permission.

The envelope spikes of paramyxoviruses are composed of two glycoproteins: the fusion protein (F) and HN (Aquaparamyxovirus, Avulavirus, Ferlavirus, Respirovirus, Rubulavirus), H (Morbillivirus), or G (Henipavirus, Orthopneumovirus, Metapneumovirus) (Table 17.2 ). Both envelope proteins have key roles in the pathogenesis of all paramyxovirus infections: The HN, H, or G proteins, respectively, are responsible for attachment to the cellular receptor(s), whereas the F protein mediates the fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane of the host cell. Unlike virus entry through the endosomal pathway, membrane fusion initiated by the paramyxovirus F protein is not dependent upon a low pH environment. Neutralizing antibodies specific for the attachment glycoprotein (HN, H, or G) inhibit adsorption of virus to cellular receptors, but antibodies specific to F can also neutralize viral infectivity.

Table 17.2.

Functions and Terminology of Virion Proteins in the Families Paramyxoviridae and Pneumoviridae

| Function | Virion Protein |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genera Aquaparamyxovirus, Avulavirus, Ferlavirus, Respirovirus, and Rubulavirus | Genus Morbillivirus | Genus Henipavirus, Orthopneumovirus, and Metapneumovirus | |

| Attachment protein: hemagglutinin, induction of productive immunity | HN | H | Ga |

| Neuraminidase: virion release, destruction of mucin inhibitors | HN | None | None |

| Fusion protein: cell fusion, virus penetration, cell–cell spread, contribution to induction of protective immunity | F | F | F |

| Nucleoprotein: protection of genome RNA | N | N | N |

| Transcriptase: RNA genome transcription | L and P/C/V | L and P/C/V | L and P |

| Matrix protein: virion stability | M | M | M |

| Other | (SH) | – | SH, M2 |

No hemagglutinating activity.

The fusion protein is synthesized as an inactive precursor (F0) that has to be activated by proteolytic cleavage. The cleaved peptides remain in close proximity by virtue of linking disulfide bonds. The specific nature of the cleavage process and the characteristics of the F0 protein differ among viruses in the different genera. However, the paramyxoviruses can be crudely divided into two groups: those with a single basic amino acid at the cleavage site and those with multiple basic amino acids at the cleavage site. The cleavage of F0 is essential for infectivity, and is an important virulence determinant for certain viruses; for example, virulent strains of avian paramyxovirus 1 (Newcastle disease virus) have multiple basic residues at the cleavage site, which means that the F protein can be cleaved by furin, an endopeptidase present in the trans-Golgi network (Table 17.3 ). The ubiquitous expression of this enzyme facilitates the production of infectious virus in all Newcastle disease virus-susceptible cells. In contrast, avirulent strains of avian paramyxovirus 1 have a single basic residue at the cleavage site, and are thus only activated by extracellular proteases with appropriate substrate specificity or trypsin-like enzymes in epithelial cells of, principally, the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. This limited “cleavability” restricts infectivity of the virus to fewer species of birds and significantly reduces their pathogenic potential. After cleavage, the newly generated amino-terminal sequence of the F1 protein has a hydrophobic domain. This fusion peptide is inserted in the membrane of the target cell to initiate fusion pore formation after the fusion process has been initiated. Depending on the genus or even the strain, the F protein can trigger fusion independently or in concert with the attachment protein.

Table 17.3.

Amino Acid Sequences at the F0 Cleavage Site of Strains of Avian Paramyxovirus 1

| Virus Strain | Virulence for Chickens | Cleavage Site Amino Acids 111–117 |

|---|---|---|

| Herts 33 | High | -G-R-R-Q-R-RaF- |

| Essex ’70 | High | -G-R-R-Q-K-RaF- |

| 135/93 | High | -V-R-R-K-K-RaF- |

| 617/83 | High | -G-G-R-Q-K-RaF- |

| 34/90 | High | -G-K-R-Q-K-RaF- |

| Beaudette C | High | -G-R-R-Q-K-RaF- |

| La Sota | Low | -G-G-R-Q-G-RaL- |

| D26 | Low | -G-G-K-Q-G-RaL- |

| MC110 | Low | -G-E-R-Q-E-RaL- |

| 1154/98 | Low | -G-R-R-Q-G-RaL- |

| Australian Isolates | ||

| Peats Ridge | Low | -G-R-R-Q-G-RaL- |

| QV4 | Low | -G-K-R-Q-G-RaL- |

| Somersby 98 | Low | -G-R-R-Q-R-RaL- |

| Dean Park | High | -G-R-R-Q-R-RaF |

| PR-32 | Low | -G-R-R-Q-G-RaF- |

| African Isolates | ||

| Chicken/MG/92 | High | -G-R-R-R-R-RaF- |

| Chicken/Mali/07 | High | -G-R-R-R-K-RaF- |

Cleavage point. Basic amino acids are shown in bold. Note that all virulent viruses have phenylalanine (F) at position 117, the F1 N-terminus.

From Swayne, D.E., Glisson, J.R., McDougald, L.R., Nolan, L.K., Suarez, D.L., Nair, V. (Eds.), 2013. Diseases of Poultry, thirteenth ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 96. Copyright © 2013 Wiley-Blackwell, with permission.

The M protein is the most abundant protein in the virion. As with other viruses with similar proteins, M interacts with the lipid envelope, the cytoplasmic “tails” of the F and attachment proteins, and the RNP. These interactions are consistent with M having a central role in the assembly of mature virions, by providing the structural link between the envelope glycoproteins and the RNP. Furthermore, M proteins are implicated in controlling the levels of RNA synthesis.

Virus Replication

Paramyxoviruses usually cause lytic infection in cell cultures, but adaptation of the virus (selection for mutants more readily able to replicate in the in vitro system) is usually necessary to achieve high-titer yields. Formation of syncytia is a characteristic feature of many paramyxovirus infections in nonpolarized cell cultures, but less so in polarized cell culture systems; similarly, syncytia are characteristic of some, but certainly not all, paramyxovirus infections in animals (see Fig. 2.2B). Acidophilic cytoplasmic inclusions composed of RNP structures are characteristic of paramyxovirus infections and, although their replication is entirely cytoplasmic, morbilliviruses also produce characteristic acidophilic intranuclear inclusions that are complexes of nuclear elements and N protein. Hemadsorption is a distinctive feature of paramyxoviruses that carry an HN protein (See Fig. 2.1D and Fig. 3.11) as well as some morbilliviruses.

Paramyxoviruses replicate in the cytoplasm of infected cells, and replication continues in the presence of actinomycin D and in enucleated cells, confirming that there is no requirement for nuclear functions. The respective attachment proteins (HN, H, G) recognize compatible ligands on the surface of target cells. For the aquaparamyxo-, avula-, ferla-, rubula-, and respiroviruses, HN binds to sialic acid residues attached to glycolipids or glycoproteins at the cellular membrane. The neuraminidase activity of these proteins is assumed to assist release of the nascent viral particles from infected cells, similar to the influenza virus neuraminiase protein. For morbilliviruses, two cellular receptors have been identified: the immune cell receptor CD150 (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM)), which is expressed on lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and the epithelial cell receptor nectin-4 explaining the strong tropism of these viruses for these cell types. For henipaviruses, ephrin B2 and B3 have been identified as cellular receptors, with single amino acid differences in the G protein determining which receptor is preferentially used. The distribution of these proteins may explain in part the systemic dissemination of henipaviruses, as these receptors are expressed on the surface of endothelial cells and brain stem neurons. For human respiratory syncytial virus (genus Orthopneumovirus), heparan sulphate and nucleolin have been identified as putative receptors, and the analogous molecules may be used by related respiratory syncytial viruses of other animals. However, the cellular receptors for many other paramyxoviruses remain to be identified, and it is highly likely that additional molecules are found to be involved in virus entry even for those with known receptors.

Following attachment, the mature F protein mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane at physiologic pH. The RNP is then released into the cytoplasm, where the N, P, and L proteins initiate transcription of mRNAs encoding the viral proteins from the genomic viral RNA, enabling the initiation of mRNA synthesis prior to de novo protein synthesis. The polymerase complex consisting of the P and L proteins initiates RNA synthesis at a single site on the 3′ end of the genomic RNA, and the genome is transcribed progressively into 6–10 discrete capped and polyadenylated mRNAs by a sequential interrupted-synthesis mechanism. This termination–reinitiation process controls the synthesis of mRNA such that the quantity of the individual mRNAs decreases with increasing distance from the 3′ end of the genome.

When the concentration of the N protein reaches a critical level, a promoter sequence at the 3′ end of the genomic RNA is transcribed and N protein binds to the nascent RNA chain. This leads the polymerase to ignore the message-termination signals resulting in the synthesis of a complete positive-sense antigenome. The N protein-encapsidated antigenome then serves as a template for the production of negative-sense genomic RNA. A second phase of mRNA synthesis then begins from the newly made genomic RNA, thus amplifying dramatically the synthesis of viral proteins.

Whereas most genes encode a single protein, the P gene of the member viruses of the family Paramyxoviridae encodes three to seven P/V/C proteins (Fig. 17.4; Table 17.2). Remarkably different strategies for maximizing the coding potential of this gene complex have evolved in the different genera. For example, the gene complex of the member viruses of the genera Morbillivirus, Henipavirus, Aquaparamyxovirus, and Respirovirus encodes 4–7 proteins, the production of which involves two distinct transcription mechanisms: (1) internal initiation of translation from different start codons; (2) insertion of nontemplated G residues into the mRNA to shift the original reading frame to that of an otherwise inaccessible one. Whereas the P protein itself is translated from a faithful mRNA copy of the complete gene, the smaller C and Y proteins are read in a different reading frame. Quite separately, the transcription of the V gene involves the insertion of an extra G nucleotide into its mRNA by polymerase site-specific stuttering (“editing”), which results in the production of a protein that displays N-terminal homology with the P protein, but with a different amino acid sequence downstream of the G insertion. Because the reading frame used to transcribe the V gene is also distinct, all three reading frames are utilized in the transcription of the P/C/V gene complex. In the case of parainfluenza virus 3, a fourth protein, D, is translated by insertion of two nontemplated G residues, and aquaparamyxo- and henipaviruses generate a W protein by the same mechanism. Members of the genera Avulavirus and Ferlavirus only produce V proteins, and in the genus Rubulavirus there are additional variations in the transcription of the P/C/V gene complex and the products formed. In contrast, in the Pneumoviridae family, each of the 10 genes encodes just a single protein, with none of the genomic coding economy and strategies utilized by members of the Paramyxoviridae family.

The P gene is essential for virus replication but the function(s) of the proteins produced by the alternative transcription/translation of the gene are yet to be completely defined. The C-terminal of the protein binds to the L protein and the N protein:RNA complex to form a unit that is essential for mRNA transcription. The N-terminal portion of the P protein is also proposed to bind to the newly synthesized N protein to permit synthesis of genomic RNA from the plus-strand template. Protein products of the P open reading frame of several paramyxoviruses, including the henipaviruses and morbilliviruses, disrupt innate host defenses (Fig. 17.5 ); specifically, mutations affecting these accessory proteins generally do not affect growth of the viruses in cell culture, but, in vivo, the mutants are attenuated. Available data suggest that the accessory proteins, especially V, compromise the interferon response network, possibly through inhibition of the signal transducers and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), and other interferon response genes. Other activities ascribed to the accessory proteins involve regulation of levels of viral RNA synthesis and assembly.

Figure 17.5.

Paramyxovirus accessory proteins target the intracellular viral pattern recognition receptors (PRR). The signaling pathways leading from the RNA helicases mda-5 and RIG-1 to induction of interferon-β (IFN-β) are shown. Paramyxovirus V proteins interact with mda-5 and prevent its activation. Sendai virus (SeV) C protein targets RIG-1, although a specific molecular interaction has yet to be shown, The NS2 (nonstructural) protein of human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) directly binds to RIG-1 and inhibits its activity. The V proteins of human parainfluenza virus 2 (HPIV2), simian virus 5 (PIV5, formerly SV5), and mumps virus (MuV) interact with and inhibit TBK1 and IKKε, and the V protein of Nipah virus (NiV) inhibits IKKε (although not TBK1). The C protein of rinderpest virus (RPV) and the W protein of NiV have uncharacterized nuclear targets that act downstream of transcription factors. CBP; IKK, inhibitory protein kappa B (IĸB) kinase; IRF3, IFN regulatory factor 3; NEMO, NFĸB essential modulator; NFĸB, nuclear factor ĸB; PRD; RIP1, receptor-interacting protein 1; TAB2/3; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1; TANK, TRAF family member-associated NFβB activator; TBK1, TANK binding kinase-1; TRAF, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor, VISA.

From Goodbourn, S., Randall, R.E., 2009. The regulation of type I interferon production by paramyxoviruses. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29, 539–548, with permission.

Virion maturation involves: (1) the incorporation of viral glycoproteins into patches on the host-cell plasma membrane; (2) the association of matrix protein (M) and other nonglycosylated proteins with this altered host-cell membrane; (3) the alignment of the RNP beneath the M protein; (4) the formation and release via budding of mature virions (Table 17.4 ).

Table 17.4.

Properties of Members of the Family Paramyxoviridae and Pneumoviridae

| The family Paramyxoviridae, containing the genera Aquaparamyxovirus, Avulavirus, Ferlavirus, Henipavirus, Morbillivirus, Respirovirus, and Rubulavirus; and the family Pneumoviridae, containing the genera Orthopneumovirus and Metapneumovirus |

| Virions are enveloped, pleomorphic (spherical and filamentous forms occur), and 150–300 nm in diameter. They are covered with large spikes (8–14 nm in length) |

| Virions contain a “herringbone-shaped” helically symmetrical nucleocapsid, 600–800 nm in length, and 18 nm (family Paramyxoviridae) or 13 nm (family Pneumoviridae) in diameter |

| Virion envelope contains two or three viral glycoproteins and one or two nonglycosylated proteins |

| Genome consists of a single linear molecule of negative-sense, single-stranded RNA, 13–19 kb in size, with seven to eight open reading frames encoding 10–12 proteins, including NP (or N), P, M, F, L, and HN (or H or G), which are common to all genera |

| Cytoplasmic replication, budding from the plasma membrane |

| Syncytium formation, intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusion bodies (genus Morbillivirus) |

Family Paramyxoviridae

Members of the Genus Aquaparamyxovirus

Salmon Paramyxoviruses

The Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus is associated with proliferative gill inflammation, a disease syndrome affecting postsmolt Atlantic salmon during their first months following transfer to seawater. The disease is characterized by pallor of the gills with inflammation and proliferation of gill epithelia resulting in significant losses to the aquaculture industry, especially in Norway. The role of Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus in proliferative gill inflammation syndrome remains uncertain as the disease appears to be of multifactorial etiology, perhaps involving several infectious agents and adverse environmental conditions. The Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus grows slowly in a rainbow trout gill cell line producing syncytia, and the virus has both hemagglutination and neuraminidase activities. The full genome of Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus has been determined showing the virus is most similar to members of the genus Respirovirus, but sufficiently distinct to be designated as the type species of the genus Aquaparamyxovirus. A similar, but apparently apathogenic Pacific salmon paramyxovirus has been isolated in a Chinook salmon cell line from returning adult Chinook salmon in rivers along the Pacific coast of North America. Partial sequence analysis of the Pacific salmon paramyxovirus confirms that this virus represents a second species of the genus Aquaparamyxovirus. Both the Atlantic and Pacific salmon paramyxoviruses can be detected using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays specific for each virus.

Members of the Genus Avulavirus

All viruses in the genus Avulavirus exhibit both hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activity. These viruses are most closely related to those in the genus Rubulavirus, but there are essential differences in the coding assignments of their respective genomes. The genus includes significant pathogens of birds, in particular virulent avian paramyxovirus 1 (Newcastle disease virus).

Newcastle Disease and Other Avian PARAMYXOVIRUS Type 1 Viruses

Newcastle disease has become one of the most important diseases of poultry worldwide, negatively affecting trade and poultry production in both developing and developed countries. The disease was first observed in Java, Indonesia, in 1926, and spread to England in the same year, where it was first recognized in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, hence the name. The disease is one of the most contagious of all viral diseases, spreading rapidly among susceptible birds. Newcastle disease virus is by definition a virulent virus, classified in the genus Avulavirus in the avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 group, but some virus strains in this group are no longer referred to as Newcastle disease virus, as they are either avirulent or of low virulence. The genus Avulavirus also contains other species of low-virulent avian paramyxoviruses, designated as avian paramyxoviruses 2–12 (see below). Natural and experimental avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 group infections have been described in more than 241 bird species from 27 of the 50 orders of birds, but this virus group may have the potential to infect most, if not all, bird species. The signs of the infection vary greatly depending on the species of bird and the strain of virus.

Because of the severe economic consequences of an outbreak of Newcastle disease in commercial poultry, the disease is reportable to the World Organization for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties (OIE)). However, in view of the wide variation in disease caused by avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strains, very specific criteria were established for defining an outbreak as Newcastle disease because of the trade implications The disease is defined as an infection of birds caused by an avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strain that meets one of the following criteria for virulence: (1) the virus has an intracerebral pathogenicity index in day-old chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) of 0.7 or greater; or (2) multiple basic amino acids have been demonstrated in the virus (either directly or deduced) at the C-terminus of the F2 protein and phenylalanine at residue 117, which is the N-terminus of the F1 protein (Table 17.4). The term “multiple basic amino acids” refers to at least three arginine or lysine residues between residues 113 and 116. Failure to demonstrate the characteristic pattern of amino acid residues as described above would require characterization of the isolated virus by an intracerebral pathogenicity index test. As a corollary, Newcastle disease can only be caused by a virulent avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strain.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Chickens, turkeys (Meleagridis gallapavo), pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), Muscovy (Cairina moschata) and domestic (Anas platyrhynchos) ducks, geese (Anser anser), pigeons (Columba livia), and a wide range of captive and free-ranging semidomestic and free-living birds, including migratory waterfowl, are susceptible to avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 infections, including virulent strains—that is, Newcastle disease virus. Most low-virulent or avirulent avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strains are maintained in migratory waterfowl and other feral birds, whereas others are maintained in domestic poultry. Newcastle disease virus strains are primarily maintained in and spread between domestic poultry, but cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) were identified as reservoir hosts in North America involved in the spread to domestic turkeys. Introduction of Newcastle disease virus into a country has been the result of smuggling of exotic birds and illegal trade in poultry and poultry products. Recent outbreaks of Newcastle disease in Australia and the United Kingdom were the result of specific mutations within the F protein gene, changing an enzootic, avirulent avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 to a virulent Newcastle disease virus.

The clinical signs associated with avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 infections in chickens are highly variable and dependent on the virus strain, thus virus strains have been grouped into five pathotypes: (1) viscerotropic velogenic; (2) neurotropic velogenic; (3) mesogenic; (4) lentogenic; (5) asymptomatic enteric. The viscerotropic, neurotropic, and mesogenic strains are those that produce moderate to high mortality rates and are officially designated as Newcastle disease. Whereas velogenic strains kill virtually 100% of infected fowl, naturally avirulent strains of avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 virus (lentogenic and enteric strains) have even been used as vaccines against Newcastle disease because they induce cross-protective antibodies.

Virus is shed for up to 4 weeks in all secretions and excretions of birds that survive the infection. Transmission occurs by direct contact between birds via inhalation of aerosols and dust particles, or via ingestion of contaminated feed and water, because respiratory secretions and feces contain high concentrations of virus. Mechanical spread between flocks is facilitated by the relative stability of the virus and its wide host range. On rare occasions, vertical transmission has been documented for lentogenic virus strains, and virus-infected chicks have hatched from virus-containing eggs. It remains uncertain whether there is vertical transmission of more pathogenic viruses, although, in one experimental study, very low doses of virulent Newcastle disease virus inoculated into eggs resulted in isolation of the virus from a few hatched chicks. Thus, vertical transmission is a rare occurrence at best.

Legal trade of caged and aviary birds and poultry and their products has played a key role in the spread of Newcastle disease virus from infected to noninfected countries, but with implementation of stringent quarantine and testing procedures such introductions are now uncommon. However, smuggling of birds and products remains a high risk factor in Newcastle disease virus epidemiology, as illustrated by introduction of the virus through fighting cocks in Southern California in 2002–2003, and by an outbreak in parts of the United States in 1991 due to smuggling of psittacine birds. Some psittacine species may become persistently infected with virulent Newcastle disease virus and excrete virus intermittently for more than a year without showing clinical signs. Virus may also be disseminated in frozen chickens, uncooked kitchen refuse, foodstuffs, bedding, manure, and transport containers. The greatest risk for spread, however, is via human activity, through mechanical transfer of infective material on equipment, supplies, clothing, shoes, and other fomites. In contrast, wind-borne transmission and movement by wild birds are much less common modes of transfer.

Respiratory, circulatory, gastrointestinal, and nervous signs are all characteristic of avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 infections in chicken. The particular set of clinical manifestations depends on the age and immune status of the host and on the virulence and tropism of the infecting virus strain. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 15 days, with an average of 5–6 days. Velogenic strains may cause high mortality—close to 100%—without clinical signs. Other velogenic strains may cause increased respiration rate, loss of appetite, listlessness, occasionally edema around the eyes and head, typically ending in a few hours with prostration and death. Respiratory signs may be absent to severe, again depending on respective strain. Some birds will have neurological signs including muscle tremors, torticollis, paralysis of legs and wings, and opisthotonos. Neurotropic strains produce severe respiratory disease followed 1–2 days later by neurological signs and near cessation of egg production. The infection produces 100% morbidity, but only 50% mortality, in adult chickens with higher mortality in young birds. Mesogenic strains produce respiratory disease, reduced egg production and, uncommonly, neurological signs, and low mortality. Lentogenic strains usually cause no disease unless accompanied by secondary bacterial infections that result in respiratory signs.

The disease in turkeys is similar but usually less severe than that in chickens with signs of respiratory and nervous system involvement. Airsacculitis, rather than tracheitis, is the most common lesion. Most infections in ducks and geese are inapparent, although a few cases of severe disease have been reported in domestic ducks. Game birds of most species have experienced outbreaks of Newcastle disease. In pigeons, avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 infections cause diarrhea and neurological signs, and the pigeon virus produces signs similar to velogenic or neurotropic virus strains in chickens.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

As noted previously, avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strains differ widely in virulence, depending on the cleavability and activation of the F protein. Avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 strains initially replicate in the mucosal epithelium of the upper respiratory and intestinal tracts, which for lentogenic and enteric strains means that disease is limited to these two systems, with airsacculitis being most prominent. For Newcastle disease strains, the virus quickly spreads hematogenously to the spleen and bone marrow, producing a secondary viremia that leads to infection of other target organs: lung, intestine, and central nervous system. Respiratory distress and dyspnea result from congestion of the lungs as well as damage to the respiratory center in the brain. Gross lesions include ecchymotic hemorrhages in the larynx, trachea, esophagus, and throughout the intestine. The most prominent histologic lesions are foci of necrosis in the intestinal mucosa, especially associated with Peyer’s patches and the cecal tonsil, submucosal lymphoid tissues, and the primary and secondary lymphoid tissues, and generalized vascular congestion in most organs, including the brain.

Virulent velogenic strains cause marked hemorrhage, in particular at the junctions of the esophagus and proventriculus, and proventriculus and gizzard, and in the posterior half of the small intestine. In severe cases, hemorrhages are also present in subcutaneous tissues, muscles, larynx, trachea, esophagus, lungs, airsacs, pericardium, and myocardium, as well as ovarian follicles of adult hens. In the central nervous system, lesions are characteristic of encephalomyelitis with neuronal necrosis.

Diagnosis

Because clinical signs are relatively nonspecific, and because the disease is such a threat, the diagnosis of Newcastle disease must be confirmed by virus isolation, virus detection by RT-PCR or immunohistochemical staining assays, and serology. The highly virulent virus may be isolated by allantoic sac inoculation of 9–10-day-old embryonating eggs from tissues (spleen, brain, or lungs) of dead birds, and both low and highly virulent virus from tracheal and cloacal swabs from either dead or live birds. Any hemagglutinating agents detected can be identified by avian paramyxovirus serotype 1-specific hemagglutination-inhibition or RT-PCR assays and subsequent sequence analysis. Determination of the virulence of each virus isolate is essential. Immunofluorescence staining of tracheal sections or smears is rapid, although somewhat less sensitive. Demonstration of specific antibodies is diagnostic only in unvaccinated flocks; the hemagglutination-inhibition assay is the test of choice because of its rapidity. Commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits provide a convenient alternative, but most ELISA tests are only applicable to chickens and turkeys. These serological tests can also be used for surveillance of avian paramyxovirus serotype 1 infections in countries where the virus is enzootic, or to monitor vaccine-induced immunity. Knowing the flock vaccination history is critical in interpreting virological and serological results, because live-attenuated virus vaccines complicate the interpretation of positive RT-PCR or virus isolation results in vaccinated flocks.

Immunity, Prevention, and Control

Hemagglutination-inhibiting and virus-neutralizing antibodies can be detected within 6–10 days of infection, and the response peaks at 3–4 weeks, and persists for over a year. While the level of hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies is an indirect correlate of immunity, neutralizing antibody titers directed against both the HN and F proteins provide a functional measure of protection. Maternal antibodies transferred via the egg yolk protect chicks for 3–4 weeks after hatching as they have a half-life of approximately 4.5 days. Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) is confined to the circulation and does not prevent respiratory infection, but it does block viremia; locally produced IgA antibodies play an important role in protection in both the respiratory tract and the intestine, although IgY secreted in the respiratory tract contributes as well.

Because Newcastle disease is a notifiable disease in most developed countries, legislative measures constitute the basis for control. Where the disease is enzootic, control can be achieved by good hygiene combined with immunization, using either live-attenuated virus vaccines containing naturally occurring lentogenic virus strains, recombinant (vectored) vaccines based on turkey herpesvirus or fowl poxvirus with avian paramyxovirus 1 F and/or HN gene inserts, or inactivated virus. These vaccines are effective and safe, even in chicks. Whereas live virus-based vaccines may be administered via drinking water or by aerosol, eye or nostril droplets, or beak dipping, the inactivated vaccines are formulated as oil emulsions and have to be injected. Recombinant vaccines are given by injection of birds in the hatchery at 1 day of age. Broiler chickens are vaccinated at least twice, whereas long-lived birds, such as laying hens, are revaccinated several times throughout their lives with inactivated vaccines. Protection against disease can be expected approximately one week after vaccination. Birds vaccinated with live virus-based vaccines will excrete the vaccine virus for up to 15 days, leading to movement restriction of these birds for 21 days after vaccination. Subcutaneously administered inactivated vaccines are usually given to pigeons. The vectored vaccines have several advantages including lacking vaccine-induced respiratory disease as can occur with live avian paramyxovirus 1 vaccines, and recombinant vaccines allow detection of field virus infections in the vaccinated population through detection of antibodies to nucleoprotein which are lacking in the recombinant vaccines alone.

Human Disease

Newcastle disease virus can produce a transitory conjunctivitis in humans. The condition has primarily been reported in laboratory workers and in members of vaccination teams exposed to large quantities of virus. Before vaccination was widely practiced, infections were also reported in workers eviscerating poultry infected with Newcastle disease virus. In developed countries, birds infected with Newcastle disease virus are not processed, but in village poultry and live markets of developing countries, Newcastle disease is common and may not preclude slaughter of infected birds. The disease has not been reported in individuals who raise poultry or consume poultry products.

Other Avian AVULAVIRUSES (Avian PARAMYXOVIRUSES 2–12)

Serologically distinct avulaviruses (avian paramyxoviruses 2–12) have been isolated from numerous species of birds, including turkeys with respiratory disease or subclinically-infected wild waterfowl, domestic ducks and geese, passerines, ostriches and psittacines, and new subtypes (10–12) have been recently discovered in rock hopper and magellanic penguins (family Spheniscidae), common snipe (Gallinago gallinago) and Eurasian widgeon (Anas penelope). However, the pathogenic significance of many of these viruses is uncertain. These viruses are commonly found in passerine and psittacine birds in import quarantine facilities, and in subclinically-infected wild waterfowl during surveillance for avian influenza viruses. An increasing number of unclassified paramyxoviruses have also been identified in these surveillance programs, that is, viruses that are not included in the avian paramyxoviruses 1–12 groupings.

Members of the Genus Ferlavirus

Fer-de-Lance and Other Ophidian PARAMYXOVIRUSES

An apparently new respiratory disease of snakes was first reported in 1976 from a serpentarium in Switzerland and a paramyxovirus-like agent was isolated (Fer-de-Lance virus). Subsequently, similar viruses have been isolated from outbreaks among several (mainly captive) species of snakes, lizards, and turtles in various areas of the world. Sequence analysis of the genome of the Fer-de-Lance virus demonstrated the virus was a member of a new genus of reptile paramyxoviruses or ophidian paramyxoviruses. Viruses in this group have been recently included in a new genus, Ferlavirus, with Fer-de-Lance virus as the type species.

Snakes infected with these viruses can develop abnormal posturing, regurgitation, anorexia, mucoid feces, head tremors, terminal convulsions, and high mortality. The lungs of affected snakes were congested, and histologic lesions included proliferative interstitial pneumonia with variable degrees of infiltration of mononuclear cells. Intracytoplasmic inclusions were present within epithelial cells of the airways. In the pancreas of several snakes, there were multifocal areas of necrosis. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the presence of viral antigen at the luminal surfaces of pulmonary epithelium, and multinucleated cells within the pancreas. A virus isolated from juvenile green anacondas was associated with a more generalized distribution and severe dermatitis and nephritis. Virus can be isolated using viper heart cells or Vero cells, but at reduced incubation temperatures (25–30°C). The ophidian paramyxoviruses hemagglutinate chicken red blood cells, which permitted the development of a serological test for screening of exposed animals. Virus can be detected by immunohistochemical staining of tissues from affected snakes, and by RT-PCR assays.

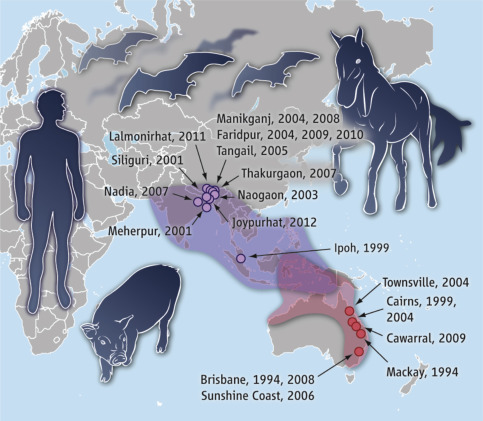

Members of the Genus Henipavirus

Zoonotic henipaviruses have caused human deaths in Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, India, and Bangladesh. Pteropus species of fruit bats that are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region from Madagascar to the South Pacific islands are the known reservoir host of henipaviruses (Fig. 17.6 ).

Figure 17.6.

Geographic distribution of Henipavirus outbreaks and fruit bats of Pteropodidae family.

Hendra Virus

In 1994, an outbreak of severe respiratory disease with high mortality occurred in thoroughbred horses stabled in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Two persons at the stable developed a severe influenza-like disease and one died. A new virus (Hendra virus) was isolated from both affected horses and a human patient, and the syndrome was reproduced experimentally in horses. There have since been sporadic but continuing cases of this devastating disease in both horses and humans, including veterinarians who performed necropsies on affected horses. Serological surveillance confirmed that a similar or identical virus infects four species of fruit bats (flying foxes, suborder Megachiroptera) on the east coast of Australia, and Hendra virus ultimately was isolated from two of these species. Molecular analyses of the viruses isolated from horses, humans, and bats indicated a close relationship with viruses in the genus Morbillivirus, thus the initial designation of the virus as “equine morbillivirus.” To avoid confusion with possible future isolates and not link the virus to a nonnatural host, the virus designation was changed to Hendra virus to reflect the location of the first isolation, and Hendra virus has now been placed in a new genus, Henipavirus, of the subfamily Paramyxovirinae.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Hendra virus is maintained by enzootic, subclinical infection in certain species of fruit bat. The precise mechanism of virus transmission from bats to nonnatural hosts such as horses and humans is uncertain, but probably involves environmental contamination by secretions or excretions from the bats (saliva, feces, urine, placental fluids). The sporadic nature of the outbreaks is likely the result of changes in the feeding behavior of the bats due to changes in food supplies or habitat incursions that facilitate close interaction of horses and bats.

Clinical signs exhibited by horses infected with Hendra virus include any combination of initial anorexia, depression, fever, and increased respiratory and heart rates, followed by respiratory or neurological signs. The clinical course is generally short, with infected horses dying quickly after the onset of clinical signs. The incubation period in experimentally infected horses was from 6 to 10 days. Cats, ferrets, hamsters, and guinea pigs, but not rabbits or mice, are susceptible to experimental infection, and cats and ferrets develop a fatal pneumonia identical to that in horses.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

Affected horses often exhibit severe pulmonary edema, with copious thick, foamy, and hemorrhagic fluid in the airways. Pericardial effusion is also characteristic. Histologically, there is severe interstitial pneumonia, with protein-rich fluid and hemorrhage in the airspaces, dilated lymphatics, vascular thrombosis, and necrosis of the walls of small blood vessels. Vasculitis is limited to small arteries, arterioles, and capillaries, with viral antigen within endothelial cells and the tunica media of affected vessels. Syncytia are present in the endothelium of lung capillaries and arterioles. Cytoplasmic inclusion bodies within these syncytia were shown by electron microscopy to consist of massed viral nucleocapsids.

The finding that ephrin-B2, a transmembrane protein that is abundantly expressed on endothelial cells, is the functional receptor for the henipaviruses potentially explains the distribution of virus in the infected host. Like those of morbilliviruses, the Hendra virus P gene encodes proteins that interfere with interferon induction and signaling. This strategy of selective interference with host innate defenses very likely enhances the severity of the infection.

Diagnosis

The epidemiology, clinical signs, and florid lesions of Hendra virus infection in horses are all distinctive, but the macroscopic lesions must be distinguished from those of African horse sickness in particular. Rapid diagnosis can be achieved using RT-PCR tests, and the virus can also be identified in tissues by immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical staining. Virus isolation can be accomplished in a variety of cell types, but Vero cells are preferred. Specimens should only be handled in high-containment facilities, and any work involving live virus must be undertaken in a Bio Safety Level 4 facility because of the devastating potential consequences of human exposure. Serological testing can be done by virus neutralization, but ELISA is much preferred because of safety issues pertaining to the requirement to use live virus in the neutralization assay.

Immunity, Prevention, and Control

Horses that survive Hendra virus infection develop very high titers of neutralizing antibodies to the virus, and a G protein-based vaccine has recently received marketing authorization in Australia. Hendra virus is a highly dangerous zoonotic pathogen that requires appropriate caution when its presence is suspected, and the availability of adequate biocontainment laboratory facilities for its diagnosis.

Nipah Virus

In 1998–99, there was an outbreak of acute encephalitis with high mortality in workers handling pigs in Malaysia. A concurrent disease in the pigs was characterized as a febrile respiratory illness, with epistaxis, dyspnea, and distinctive coughing in young pigs. Some older animals showed neurological signs such as ataxia, paresis, seizures, and muscle tremors. While the mortality in humans was around 40%, the disease severity in pigs was moderate, suggesting Japanese encephalitis virus as a causative agent. However, a morbillivirus was isolated from human cases and then from the affected pigs. The virus was antigenically related to Hendra virus, but subsequent sequence analysis identified a new species in the genus Henipavirus, now designated as Nipah virus.

Epidemiological investigations identified fruit bats as the source of the virus, analogous to the epidemiology of Hendra virus. Nipah virus occurs in several species of fruit bat in Southeast Asia, with infections being reported as far west as India. In experimentally infected fruit bats, virus can be detected by virus isolation or by RT-PCR in urine samples. As with Hendra virus, transmission from the fruit bats to animals likely occurs in agricultural facilities in close proximity to the bat feeding areas. The virus can easily be spread among the exposed pigs through the respiratory route. Workers handling the pigs or pig carcasses also became infected, and there was evidence of human-to-human spread. In Malaysia, the infection in pigs was known as “barking pig syndrome” because of the characteristic cough. Virus can consistently be isolated from pharyngeal swabs of experimentally infected pigs starting at day 4 postinfection, and the virus spreads horizontally to control pigs. Cats can also be infected with Nipah virus and can transmit the virus to contacts.

The pathology of Nipah virus disease in pigs and humans is similar to that caused by Hendra virus. A prominent feature in the human cases was a vasculitis with endothelial cell damage, necrosis, and syncytial giant cells in the affected vessels. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed that abundant viral antigen was present in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the small blood vessels. Severe dysfunction of brain stem neurons occurs in humans with Nipah virus encephalitis, probably as a result of the strong tropism of the attachment G protein of Nipah virus for the ephrin-B3 receptor that is abundantly expressed on these cells. Naturally infected pigs developed tracheitis and bronchointerstitial pneumonia with hyperplasia of the airway epithelium. Sero-surveys indicate that many pigs have subclinical infections.

Nipah virus appears to be a more substantial threat to agriculture and humans than Hendra virus, in part because of the role of swine as amplifying hosts. Experimental vaccines have been developed that are efficacious in different animal models, but there are no licensed products for animal or human use at this time. Rapid and sensitive diagnostic tests are available, including RT-PCR assays, and immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining assays to detect viral antigen. As with Hendra virus, immunoassays are routinely used for serological diagnosis because of the biosecurity issues associated with handling live Nipah virus. As with Hendra virus, work with Nipah virus must be confined to a Bio Safety 4 Laboratory.

Other HENIPAVIRUSES

Henipavirus infection of multiple species of African bats, including West African fruit bats (Eidolon helvum), confirms that viruses identical or related to Nipah and Hendra viruses circulate in other regions of the world but in different bat reservoir hosts. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses indicate that these chiropteran African henipaviruses may be the ancestors of those that occur in Australia and Asia.

Members of the Genus Morbillivirus

Members of the genus Morbillivirus all employ the same replication strategy and all lack neuraminidase activity. They cause mild to severe disease syndromes in their respective hosts that share a similar pathogenesis.

Rinderpest Virus

Since 2011, rinderpest has become only the second infectious disease, after smallpox, to be officially eradicated globally. Eradication of rinderpest was the result of an intensive and coordinated effort that involved active surveillance, animal culling, movement restrictions, and an intense vaccination program.

Rinderpest is one of the oldest recorded plagues of livestock. The causative agent, rinderpest virus, was first shown to be a filterable virus in 1902. On the basis of phylogenetic analysis, it has been suggested that rinderpest virus is the archetype morbillivirus, speculated to have given rise to canine distemper and human measles viruses some 5000–10,000 years ago. Rinderpest most probably arose in Asia, and was described in the 4th century. Devastating epizootics of rinderpest occurred across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, and a massive epizootic spread throughout sub-Saharan Africa in the late 19th century (1887–97), decimating populations of cattle and certain wildlife. The 1920 outbreak in Europe led to the founding of the OIE—the World Organization for Animal Health—that today coordinates animal infectious disease authorities globally to regulate animal diseases and to facilitate science-based international trade. The historical impact of rinderpest was most eloquently summarized in 1992 by Drs. Gordon Scott and Alain Provost when they described the disease as “the most dreaded bovine plague known, belongs to a select group of notorious infectious diseases that have changed the course of history. From its homeland around the Caspian Basin rinderpest, century after century, swept west over and around Europe and east over and around Asia with every marauding army causing the disaster, death and devastation that preceded the fall of the Roman Empire, the conquest of Christian Europe by Charlemagne, the French Revolution, the impoverishment of Russia and the colonization of Africa.”

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Rinderpest is a highly contagious disease of cattle and other artiodactyls. The host range includes domestic cattle, water buffalo, yak, sheep, and goats. Domestic pigs can develop clinical signs and were regarded as an important virus reservoir in Asia. Among wild animals, wildebeest, waterbuck, warthog, eland, kudu, giraffe, deer, various species of antelope, hippopotami, and African buffalo are all susceptible, although there is a wide spectrum of clinical disease that is most severe in African buffalo, wildebeest, and giraffe, and invariably mild or subclinical in several species of antelope and hippopotamus. It may well be that all artiodactyls are susceptible to infection, but not all will exhibit obvious clinical signs. Other species, including rodents, rabbits, and ferrets, are susceptible to experimental infection, but are unlikely to have contributed to the epidemiology of the disease.

The clinical features of individual outbreaks of rinderpest reflected the virulence of the respective virus strain and the susceptibility of the individual animal host. In its typical manifestation in cattle and other susceptible wild or domestic ruminant species, rinderpest was an acute febrile disease with morbidity in susceptible populations approaching 100% and a mortality of 25–90%. Some of the indigenous cattle breeds in Africa are highly susceptible, whereas other breeds experienced lower mortality (less than 30%). After an incubation period of 3–5 days, there is a prodromal phase with rapid increase in temperature, decrease in milk production, labored breathing, and cessation of feeding. This is followed by congestion of the mucous membranes of the conjunctiva and oral and nasal cavities, and an abundant serous or mucoid oculonasal discharge. Severe cases are characterized by extensive, typically coalescing, erosion and ulceration of the epithelial lining of the entire oral cavity; plaques of caseous necrotic debris overlie foci of epithelial necrosis and inflammation, and affected animals typically drool saliva because of the discomfort associated with swallowing. This is followed by a phase of severe bloody diarrhea and prostration caused by involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. Finally there is a precipitous drop in temperature, at which time affected animals may die from dehydration and shock. Young animals are predisposed to severe disease. A milder course of disease is characteristic of infection of susceptible animals with less virulent virus strains, and inapparent infection invariably occurs within certain host species such as impala and hippopotamus. Disease also is often less severe in sheep and goats. These mild infections are characterized by reduced clinical signs and mucosal injury, little or no diarrhea, and considerably lower mortality.

Once established in a population, rinderpest virus caused a considerably milder disease. The attenuation of rinderpest in enzootic areas probably reflected both the selection of less virulent virus strains with the highest potential for transmission, and immunity within populations of susceptible animals. The infection was maintained in enzootic areas in younger animals that became infected as their maternal immunity waned. Rinderpest virus also was maintained for long periods through subclinical infections in wildlife, which then served as a reservoir for infection of cattle. The virus rapidly regained its virulence when spreading from enzootic foci to cause epizootics in susceptible populations.

Rinderpest virus is spread in all the secretions and excretions of affected animals, in greatest quantities during the acute febrile stages of the disease. The virus is relatively fragile in the environment, so transmission in enzootic areas predominantly occurred by direct contact between infected and susceptible animals. However, aerosol and fomite transmission are also possible. The virus can persist for several days in infected carcasses. Because infected cattle excrete large amounts of virus during the incubation period before the appearance of clinical signs, acutely infected but still asymptomatic animals often introduced rinderpest virus into disease-free areas. Similarly the disease was also brought into new areas by importation of subclinically infected sheep, goats, and possibly other ruminants and wildlife. Subclinically infected swine of any species may act as a source of infection for cattle, but only Asian breeds of swine and warthogs show clinical signs of rinderpest virus infection.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

After oronasal infection via aerosols or direct contact, rinderpest virus first replicates within mononuclear leukocytes in the tonsils and mandibular and pharyngeal lymph nodes. Within 2–3 days, virus is transported during leukocyte-associated viremia to lymphoid tissues throughout the body, and to the epithelium lining the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. The virus utilizes the bovine equivalent of the human CD150 (SLAM) as an immune cell receptor, which is consistent with the cellular and tissue tropism of rinderpest virus, as this molecule is present on immature thymocytes, activated lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. The virus also infects and replicates in endothelial cells and some epithelial cells, presumably using the bovine nectin-4 molecule, causing multifocal necrosis and inflammation in a variety of mucous membranes.

Profound lymphopenia characteristically occurs in infected animals, probably as a consequence of virus-mediated destruction of lymphocytes in all lymphoid tissues, including the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (Peyer’s patches). Like all morbilliviruses, rinderpest virus infection quickly results in the rapid onset of severe immunosuppression, but induces a robust immune response in survivors that confers lifelong protection from reinfection. Although the underlying mechanisms have yet to be characterized for rinderpest virus, like other morbillivirus infections of animals, it is likely that a lethal course of disease is associated with a weak and transient, or even absent, activation of the innate immune response (see Chapter 4: Antiviral Immunity and Virus Vaccines) and lack of any sustained adaptive immune response. In contrast, animals that manifest sublethal disease typically exhibit vigorous induction of interferons and other innate cytokines and sustained and broad B and T cell responses.

In severely affected animals, profuse diarrhea rapidly leads to dehydration and fatal hypovolemic shock. The lesions present in infected animals reflect the virulence of the infecting virus strain, and in severe, acute cases include: marked dehydration (eg, sunken eyes); disseminated erosions and ulcers throughout the mucosal lining of the oral cavity, esophagus, and forestomachs; diffuse hemorrhage and necrosis of the mucosa of the abomasum; focal congestion and hemorrhage in the mucosa of the intestinal tract, with hemorrhagic necrosis of Peyer’s patches. Segmental vascular congestion within the mucosa of the large intestine can produce characteristic “zebra stripes.” Hemorrhage and congestion can also occur in the mucosal lining of the urinary bladder and upper respiratory tract and trachea. Secondary bacterial pneumonias are common because of the severe immunosuppression. Histologic lesions include widespread necrosis of lymphocytes and multifocal epithelial necrosis. In addition, epithelial syncytia and intracytoplasmic and, less often, intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies are characteristically present in affected tissues.

Diagnosis

In countries where rinderpest was previously endemic, clinical diagnosis was usually considered sufficient. Rinderpest historically could be confused with other diseases causing mucosal congestion, erosions or ulcers, such as bovine viral diarrhea, malignant catarrhal fever, and, in the early stages, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and foot-and-mouth disease. These diagnostic problems have largely been resolved with the development of specific PCR tests for all of these “look-alike” diseases. Quantitative (real-time) RT-PCR assays are now available for rinderpest virus that allow its rapid distinction from the related peste des petits ruminants virus. Historically, different cell lines and primary cultures were used for virus isolation, especially primary bovine kidney cells. Virus neutralization and, more recently, ELISA have been used to assess the prevalence of rinderpest virus infection in a given region.

Immunity, Prevention, and Control

Cattle that survive rinderpest virus infection have lifelong immunity. Neutralizing antibodies appear 6–7 days after the onset of clinical signs, and maximum titers are reached during the 3rd and 4th weeks after infection. With the advent of molecular typing, three distinct genetic lineages of rinderpest virus were defined; two from Africa and one from Asia. All strains belong to the same serotype, which permitted the use of a vaccine that contained a single virus strain. Prior to eradication, lineage 3 was restricted to Asia, lineage 2 to East and West Africa, and lineage 1 to Ethiopia and Sudan. As of April 2007, there were no reports of rinderpest virus infection in any countries reporting to OIE, which includes all of Asia and Africa. Kenya became the last African country to report a self-declared free status. The virus was declared eradicated globally by the OIE in May 2011. Strict restriction on possession and work with the virus is necessary to ensure that the virus never reemerges.

The rinderpest eradication campaign was based on veterinary public health measures designed to prevent introduction of the virus in virus-free areas. Importation of uncooked meat and meat products from infected countries was forbidden, and zoo animals were quarantined before being transported to such countries. In countries with enzootic rinderpest and where the disease had a high probability of being introduced, live-attenuated virus vaccines were used. Early rinderpest vaccine strains were produced by virus passage in rabbits (lapinized vaccine), embryonated eggs (avianized vaccine), or goats (caprinized vaccine). In the 1960s, a live-attenuated vaccine produced in cell culture (the so-called Plowright vaccine (after its inventor, Walter Plowright) or tissue culture rinderpest vaccine) was developed that was instrumental in eliminating the disease because it induced lifelong immunity and was inexpensive to produce. In fact, it was one of the best vaccines available for any animal disease, even though it was thermolabile initially and required a well-maintained “cold chain”—a difficult practical problem in many areas where rinderpest previously occurred. A thermostable version of the Plowright vaccine was developed in the 1990s and used extensively for the eventual global eradication of rinderpest. As the number of infected animals decreased, vaccination was suspended in order to facilitate serological surveillance, since the vaccine-induced immune response was indistinguishable from that of wild-type virus infections. Although marker vaccines have been developed to circumvent this problem, they were never widely used.

Peste des Petits Ruminants Virus

Peste des petits ruminants is a highly contagious, systemic disease of goats and sheep that is similar to rinderpest and caused by a closely related morbillivirus, peste des petits ruminants virus. The infection was first described in West Africa, but now occurs in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and the Asian subcontinent, including Nepal, Bangladesh, and Tibet. There are suggestions that this virus has recently moved into areas from which rinderpest virus was previously eradicated. Peste des petits ruminants virus is grouped into four distinct lineages based on the sequence of the F protein, but there is only one serotype. Lineages 1 and 2 occur in West Africa, lineage 3 in East Africa, the Middle East, and southern India, and lineage 4 extends from the Middle East to Tibet. There is some correlation between virulence and lineage; for example, lineage 1 strains in West Africa are more virulent than lineage 2 strains from the same area.

Transmission of the virus is similar to that of rinderpest, and generally requires close contact with infected animals. Virus is excreted for several days before the onset of significant clinical signs, such that spread of the virus is enhanced with the comingling of animals. Wild animals are not believed to play a major role in the epidemiology of peste des petits ruminants virus infection. The natural infection occurs in sheep and goats, with goats being more severely affected. Different breeds of goat show different morbidity rates, and the course of disease is generally more severe in young animals. Case fatality rates can be as high as 85% in goats, but rarely above 10% in sheep. Peste des petits ruminants virus is similar to rinderpest virus, and cattle can be experimentally infected with both viruses; some putative cases of rinderpest may in fact have been peste des petits ruminants virus instead. In goats, a febrile response occurs at 2–8 days after infection. Clinical signs include fever, anorexia, nasal and ocular discharges, necrotic stomatitis and gingivitis, and diarrhea. Bronchopneumonia is a frequent complication. The course of the disease may be peracute, acute, or chronic, depending on strain of virus, age, immune status, and breed of host. The pathogenesis of the infection is probably similar or identical to that of other morbilliviruses, beginning with an infection of immune cells and subsequent viremia, leukopenia, and systemic infection, principally involving lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and the epithelial cells lining the alimentary tract. At necropsy, there are extensive erosions and necrosis in the mucosal lining of the oral cavity, esophagus, abomasum, and small intestine. Regional lymph nodes are enlarged and there typically is an interstitial pneumonia.

Diagnosis of the disease, aside from clinical signs, has shifted from virus isolation to quantitative RT-PCR assays. These tests can distinguish between peste des petits ruminants and rinderpest viruses, which has been critical in the rinderpest eradication program. Virus isolation in primary lamb kidney cells was used to obtain isolates for further characterization and comparison. Virus neutralization tests can be used to distinguish between antibodies induced in animals by peste des petits ruminants and rinderpest virus infections. While effective, the rinderpest vaccine is no longer used to prevent peste des petits ruminants. Instead, a live-attenuated vaccine based on a lineage 2 virus isolate (Nigeria 75/1) is now most commonly used. With the successful eradication of rinderpest, proposals are being considered for an eradication of peste des petits ruminants virus.

Canine Distemper Virus

Canine distemper is a highly contagious acute febrile disease of dogs that has been known since at least 1760. Edward Jenner first described the course and clinical features of the disease in 1809; its viral etiology was demonstrated in 1906 by Carré. Since introduction of a vaccine in the 1960s, canine distemper virus infections have become increasingly rare in domestic dogs in industrialized countries. Clinical cases that do occur invariably are in unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated dogs, especially in rescue shelters or adoption centers. The continued presence of canine distemper virus in countries with high vaccine coverage is most likely due to its circulation in wildlife reservoirs such as raccoons, foxes, and wild canids. Canine distemper virus has also emerged as a significant pathogen of the large species in the family Felidae. Beginning in 1994, thousands of African lions died in a succession of epizootics, with free-roaming canids (hyenas, feral dogs) being the most likely source of the virus.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

The host range of canine distemper virus encompasses all species of the families Canidae (dog, dingo, fox, coyote, jackal, wolf), Procyonidae (raccoon, coatimundi, panda), Mustelidae (weasel, ferret, fishers, mink, skunk, badger, marten, otter), the large members of the family Felidae (lions, leopards, cheetahs, tigers), and the collared peccary (Tayassu tajacu). The highly publicized outbreaks of distemper in lions (Panthera leo) in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and cases in the Chinese leopard (Panthera pardus japonensis) and other large cats in zoos, have graphically confirmed the capacity of the virus to invade new host species. In addition to the large cats, canine distemper virus also causes high mortality in black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes), the bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis), red pandas (Ailurus fulgus), hyenas (genus Hyaena), African wild dogs (genus Lycaon), raccoons (genus Procyon), palm civets (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), Caspian (Pusa caspica) and Baikal (Pusa sibirica) seals, and different species of macaque. The high morbidity and mortality rates in rhesus monkey colonies in Asia has raised concerns of the zoonotic potential of canine distemper virus should measles vaccine rates fall in humans. The threat of this virus to susceptible and potentially endangered wildlife species is expected to increase with the relentless human encroachment into historically undeveloped areas of the world. Furthermore, carnivores other than domestic dogs can serve as major reservoir hosts of the virus in rural Africa, notably hyena, fox, and jackals. Similarly, raccoons disseminate the virus to other susceptible species in North America.