Abstract

Background

Treatment burden is an emerging concept in health care literature. It can complicate the patients’ condition and perhaps result in poor adherence to treatment, which is linked to worse clinical outcomes. However, until now there is no definition for treatment burden recognized by all stakeholders. This review was prepared in order to find what available definitions for treatment burden are present in the literature.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was prepared looking for definitions of treatment burden in adult patients. Articles about adults aged 18 years or older from both genders with one or more medical conditions that contained a (new) definition of treatment burden were included. The search approach consisted of conventional systematic review database searching of multiple resources including Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts, and full papers.

Results

The searches resulted in 8045 records, of which 16 articles were included. Based on quality appraisal criteria, we decided that two definitions had better evaluations than the rest of the definitions, the first one defining it as the impact of the ‘work of being a patient’ on functioning and well-being, the second as the actions and resources they devote to their healthcare.

Conclusion

We consider the definition concentrating on actions and resources patients devote to their healthcare, including difficulty, time, and out-of-pocket costs dedicated to the healthcare tasks such as adhering to medications, dietary recommendations, and self-monitoring as the one probably comprising most domains of Treatment Burden that we have found in our search in the existing literature. However, adding even more domains to this definition and differentiating explicitly between patient's perception and caregiver's perception in the definition could in our opinion result in an improved definition. Also patients' evaluation of this definition is commendable.

Keywords: Health sciences, Quality of life, Disability, Decision sciences, Well-being, Aging and life course

Health Sciences; Quality of Life; Disability; Decision Sciences; Well-Being; Aging and Life Course.

Contribution of the Paper.

Already known about the topic:

-

•

Treatment burden, already known in single chronic conditions, is an emerging concept also in the scientific literature about multimorbidity. It includes not only the burden of medication but that of all types of health care interventions and actions.

-

•

Treatment Burden can complicate the patients' condition and result in poor adherence to prescribed treatments and self-care, which could be linked to worse clinical outcomes, such as more hospitalizations, higher mortality, and poor health-related quality of life.

-

•

A definition for treatment burden recognized by all stakeholders, is to this day not in use.

This paper adds:

-

•

The results of a search for all the available definitions of treatment burden present in the existing literature.

-

•

Discussions on the (missing of) domains of Treatment Burden.

1. Introduction

Chronic diseases affect 38 million people worldwide, with nearly three quarters (28 million) occurring in low and middle income countries (Mendis, 2014). There are various definitions (van den Akker et al., 1996), and an association with aging, and multi-morbidity (Marengoni et al., 2011; Barnett et al., 2012). Elderly populations usually have a higher prevalence of chronic diseases, often leading to polypharmacy. According to a medical literature review by Bushardt et al. (2008) polypharmacy is defined as the use of more than five medications, or the use of at least one potentially inappropriate drug. As polypharmacy continues to rise, it poses a significant burden to patients: non-adherence to treatment was most often linked to the burden of treatment, resulting from medication characteristics, including the number of medications, and is thus associated with treatment burden (Sav et al., 2013b).

Treatment burden is a concept that has been getting more exclusive interest in the literature recently; it includes not only the burden of medication but all types of health care interventions, and also the patients' perspective (Eton et al., 2012). Thus it can complicate the patients’ condition and result in poor adherence to prescribed treatments and self-care, which is linked to worse clinical outcomes, such as more hospitalizations, higher mortality, and poor health-related quality of life (Ridgeway et al., 2014). However, a definition for treatment burden recognized by all stakeholders, is to this day not in use.

In the present study, we performed a systematic literature review to search for all the available definitions of treatment burden in order to find a definition, that is applicable for multiple diseases, is well-articulated, includes the main themes that are related to treatment burden such as work patients must do and factors that exacerbate the burden (Eton et al., 2015), is applicable in clinical practice, and differs from other types of burden for example caregiver burden or disease burden. Also, the experiences of patients themselves should be taken into account by patient participation in forming a treatment burden concept, and preferably patients should have a say about the definition of treatment burden as well.

This might also be the first step toward finding a measurement tool for treatment burden. We believe that finding a well-articulated definition for treatment burden will help health-care professionals to identify the patients who are at risk and try to find ways to minimize this burden. However, as we could not find any criteria to evaluate the definitions of treatment burden, we constructed criteria based on the previously stated main points in order to evaluate the definitions found.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This research is a systematic review of the literature on treatment burden definition. The aim was to find definitions of treatment burden in adult patients (above 18 years of age). The search was performed with help from a search expert (Ms. Kate Misso), and two reviewers (AA &TvM) have assessed the literature independently and discussed the findings together.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were any studies that defined treatment burden, including both qualitative and quantitative studies. There were no geographical restrictions or language limitations in our search. Moreover, there were no period restrictions. We excluded articles that discussed a young population below 18 years of age, because we assessed that the treatment burden in pediatric patients will be also be strongly associated with caregiver burden due to family involvement. Also any definition that was solely copied from another article's definition was excluded.

2.3. Literature searchs

Identification of information from qualitative reviews presents a challenge which cannot be met solely by ‘classic’ systematic reviews searching (Nicola et al., 2010). The well-established methods employed to identify quantitative evidence (Higgins and Green, 2011; Systematic Reviews, 2009) do not always translate well into effective searching for qualitative literature (Nicola et al., 2010). Gallacher (2013a, b) (Gallacher et al., 2013a) recommended undertaking several inter-locking search steps iteratively, to maximize sensitivity and recall. The search method for this project was guided by Gallacher (2013a, b) (Gallacher et al., 2013a) and incorporated the following search steps: firstly, rapid appraisal to identify existing systematic reviews and key citations on treatment burden to identify additional primary studies, experts, and relevant organizations and websites. Secondly, generation and exploration of a test set of core references throughout the planning, scoping, rapid appraisal and reference list checking processes. The details of the literature search for step 1 and 2 are attached in Appendix 1. Thirdly, iterative structured searches were performed to identify relevant qualitative studies and qualitative components in quantitative studies investigating treatment burden with three search facets: qualitative methods, treatment burden, and age. The following databases were searched for relevant studies: Embase and Medline (via OvidSP), CINAHL and PsycINFO (via EBSCO), and Science Citation Index (SCI) (via Web of Science). Performance and recall of these searches were determined by checking how many of the core reference set were retrieved.

Any core references which were 'missed' were investigated to determine whether the strategy should be revised, or whether a further complementary search should be conducted. The details of databases search are attached in Appendix 2.

2.4. Quality appraisal

As we did not find any criteria to evaluate the definition of treatment burden, we constructed own criteria, and decided that the following are important points to judge a definition: a definition that is usable in multiple diseases (M), is well-articulated and concise (W), includes main domains of treatment burden (D), is applicable in clinical practice (C), differs from other types of burden (T), and is based on patients’ participation in the research (P). As the origin of the definitions in the articles were not always mentioned, we did not take their construction into account.

The evaluation of the definitions was done by two reviewers (AA & TvM) independently. Each reviewer gave a rating out of six based on how many criteria the definition did meet. If a discrepancy existed, a third party was involved. The details of the quality appraisal can be seen in Appendix 3.

2.5. Data extraction

An Excel file with all the information that needed to be extracted from the articles was constructed. The file is composed of three sheets: articles’ details (location, center, setting and funding details), study design (study aim, population sampling, source of data and comments), definitions (treatment burden definition, type of disease, rating, criteria, and other definitions).

Two reviewers (AA & TvM) discussed the contents of the sheets. The table of data extraction is attached in Appendix 3.

3. Results

3.1. Searching and screening

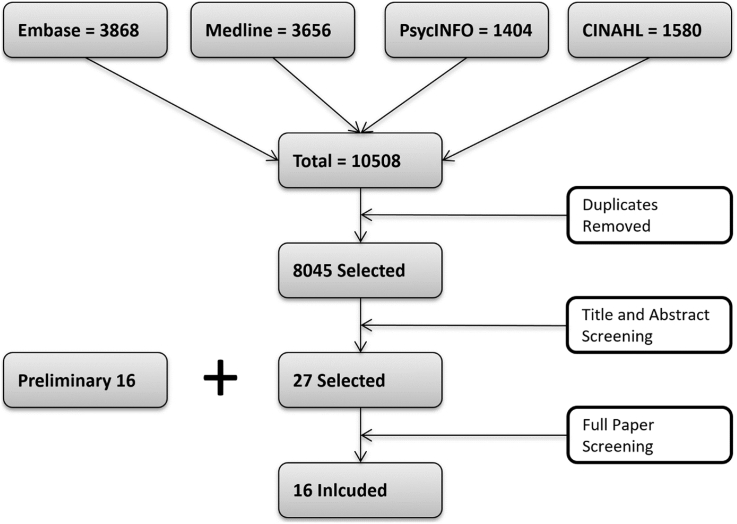

Our rapid appraisal in multiple sources and focused exploratory Internet searches using Google search engine resulted in 16 included articles that we set as a core reference. Our structured search from the databases Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL resulted in 10508 articles in total. Each database had the following results: Embase 3868, Medline 3656, PsycINFO 1404, CINAHL 1580. Details of preliminary search can be found in Appendix 1, details of search terms and the results of search strategy in each database are in Appendix 2.

After removing the duplicated results via EndNote X6, there were 8045 included articles, then 380 duplications were removed manually. Two reviewers (AA & RA screened the title and abstracts independently, and ended with 27 articles, with 16 of them already in the core references. After reading the full papers, the articles that met the inclusion criteria were included. We ended up with 16 included articles, all of them from the preliminary search (see Figure 1). The articles that were excluded did not contain a definition for treatment burden. Therefore, no new articles were found in the structured search, though the structured search found all the core articles we had in the preliminary search.

Figure 1.

Flow chart demonstrating papers included in the definition of treatment burden review.

3.2. Definitions assessment

Based on our quality appraisal criteria, two definitions had a better evaluation than the rest. The list of definitions can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data extraction of the definitions.

| ID | Treatment Burden Definition | Rating (out of 6) | Criteria∗ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abu Dabrh et al. (2015) | The burden of treatment: multi-dimensional phenomenon describes the added and ongoing workload (i.e. requirements and demands) for patients in order for them to adhere to recommendations made by their clinicians to manage their morbidity and wellbeing. It also reflects the barriers patients face as they navigate through this journey of healthcare. Treatment workload encompasses the tasks carried out by patients to manage their illness (e.g. taking medications, reading information leaflets, arranging transportation to appointments, making lifestyle changes). | 3 | M, D, T |

| Boehmer et al. (2016) | Treatment burden can be defined as treatment work, delegated by health care systems to patients and its impact on their functioning and well-being; there are growing demands on patients to organize their own care and self-manage to comply with complex regimens. | 2 | M, T |

| Bohlen et al. (2012) | We defined BOT as treatment related effects that limit the patient's ability to participate in activities and tasks that are crucial to his or her quality of life and that are not attributable to underlying disease. | 3 | M, W, T |

| Boyd et al. (2014) | Treatment burden is defined here as a patient's perception of the aggregate weight of the actions and resources they devote to their healthcare, including difficulty, time, and out-of-pocket costs dedicated to the healthcare tasks such as adhering to medications, dietary recommendations, and self-monitoring. | 5 | M, W, D, C, T |

| Demain et al. (2015) | “the self-care practices that patients with chronic disease must perform to enact management strategies and respond to the demands of healthcare providers and systems”. | 2 | W, T |

| Eton et al. (2012) | The workload of health care and its impact on patient functioning and well-being. "Workload'' includes the demands made on a patient's time and energy due to treatment for a condition(s) as well as other aspects of self-care (eg, health monitoring, diet, exercise). “Impact” includes the effect of the workload on the patient's behavioral, cognitive, physical, and psychosocial well-being. | 2 | M, T |

| Eton et al. (2016) | Treatment burden refers to the personal workload of healthcare, including treatment and self-management of chronic health conditions, and the impact of this workload on patient functioning and well-being. Workload identifies the activities that patients are asked or required to do in order to care for their health (e.g., taking medications, maintaining medical appointments, monitoring health status, engaging in physical therapy). Impact refers to a patient's perception of the effect of the workload on role, social, physical, and psychological functioning. Financial challenges, confusion about medical information, and challenges with the healthcare system may add to the weight of the burden that is felt by the patient. | 3 | M, D, T |

| Fraser and Taal (2016) | Treatment burden comprises objective treatment related tasks (e.g. attending appointments, taking multiple medications, dose-adjustment, tests, interventions, including attending dialysis) and perceived treatment burden (patients' experience of the demands placed on them by clinicians and the health system). | 3 | M, D, T |

| Gallacher et al. (2013a) | Treatment burden can be defined as the “workload” of health care that patients must perform in response to the requirements of their healthcare providers as well as the “impact” that these practices have on patient functioning and well being. “Workload” includes the demands made on a patient's time and energy due to treatment for a condition (s) (e.g. attending appointments, undergoing investigations, taking medications) as well as other aspects of selfcare (e.g. health monitoring, diet, exercise). “Impact” includes the effect of the workload on the patient's behavioural, cognitive, physical, and psychosocial well-being. | 3 | M, D, T |

| Gallacher et al. (2013b) | ‘Treatment burden’ is a novel concept describing the self-care practices that patients with chronic disease must perform to enact management strategies and respond to the demands of health care providers and systems. Individuals will vary in their capacity to accommodate and enact such practices, which may have a marked impact on patient functioning and well-being, and on adherence to management plans. | 1 | M |

| Heckman et al. (2015) | Demands associated with disease management represent treatment burden. | 1 | M |

| Sav et al. (2013a) | Treatment burden refers to the consequences they experience as a result of undertaking or engaging in treatment, such as medications, therapies, medical interventions etc. | 2 | M, W |

| Sav et al. (2013b) | Treatment burden: a person's subjective and objective overall estimation of the dynamic and multidimensional burden that their treatment regimen for chronic illness has imposed on them and on their family members. | 1 | W |

| Tran et al. (2012) | Treatment burden can be defined as the impact of health care on patients' functioning and well-being, apart from specific treatment side effects. It takes into account everything patients do to take care of their health: visits to the doctor, medical tests, treatment management, and lifestyle changes. | 3 | M, W, C |

| Tran et al. (2014) | Treatment burden is defined as the ‘work’ of being a patient and its effect on the quality of life (QOL) of patients. It represents the challenges associated with everything patients have to do to take care of themselves (e.g. medication intake, drug management, self-monitoring, visits to the physician, laboratory tests, lifestyle changes, administrative tasks to access and coordinate care). | 3 | M, D, T |

| Tran et al. (2015) | Treatment Burden Defined as the impact of the ‘work of being a patient’ on functioning and well-being. This work includes drug management, self-monitoring, visits to the doctor, laboratory tests, lifestyle changes, and other actions that take place in addition to the other work patients and their caregivers must do as part of life. | 4 | M, W, D, C |

∗ The criteria are based on the quality appraisal mentioned in the Methods: M: usable in multiple diseases; W: well-articulated and concise; D: includes main domains of treatment burden; C: applicable in clinical practice; T: differs from other types of burden; P: based on patients' participation.

The first one is by Tran, V., et al. (2015) (Tran et al., 2015). They defined treatment burden as “the impact of the ‘work of being a patient’ on functioning and well-being. This work includes drug management, self-monitoring, visits to the doctor, laboratory tests, lifestyle changes, and other actions that take place in addition to the other work patients and their caregivers must do as part of life.” The definition is usable for multiple diseases, is well-articulated, based on factor analysis to verify the domains in the created scale, mentions a couple of treatment burden domains such as drug management and self-monitoring, and it is applicable in the clinic. However, the drawbacks of Tran's definition are including the caregiver burden into the definition of treatment burden (and not differentiating it from the patients' burden), and not mentioning patients' participation in formulating the definition. The second definition is by Boyd, C. M., et al. (2014) (Boyd et al., 2014). They defined treatment burden as “a patient's perception of the aggregate weight of the actions and resources they devote to their healthcare, including difficulty, time, and out-of-pocket costs dedicated to the healthcare tasks such as adhering to medications, dietary recommendations, and self-monitoring.” The definition is usable in more diseases, more concise than Tran's, is well-articulated, and contains main domains of the treatment burden framework constructed by Eton et al. (2015) such as difficulty, out-of-pocket costs, and time spent on the health-care tasks. It is also applicable in the clinical practice. However, Boyd's definition could be improved by stating the separation of treatment burden from caregiver burden clearly, and be based on patients' participation and evaluation in the research project.

Regarding the other definitions, five of them (Abu Dabrh et al., 2015; Eton et al., 2016; Fraser and Taal, 2016; Gallacher et al., 2013a; Tran et al., 2014) were not very concisely articulated and/or not applicable in clinical practice. Two (Boehmer et al., 2016; Eton et al., 2012) fulfilled two criteria of the quality appraisal (usable in multiple diseases, and different from other types of burden). Two (Gallacher et al., 2013b; Heckman et al., 2015) were usable in multiple diseases only. One (Sav et al., 2013b) was only well articulated. The rest either did not include the main domains of treatment burden (Bohlen et al., 2012; Demain et al., 2015; Sav et al., 2013a; Tran et al., 2012), lacked differentiation from other types of burden (Sav et al., 2013a; Tran et al., 2012), were not usable in multiple diseases (Demain et al., 2015) or not applicable in the clinic (Bohlen et al., 2012; Demain et al., 2015; Sav et al., 2013a). None of the definitions were formed based on patients’ participations and evaluation of the definition.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this review was to find available definitions in the present scientific literature of treatment burden in adult patients. Next, we tried to evaluate these according to our appraisal criteria mentioned in the methods. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review regarding the definition of treatment burden. In this review, we identified 16 definitions of treatment burden, 4 of them on specific diseases but with a possibility to contain different diseases.

Treatment burden is a broad concept and involves many domains (Eton et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2015). Until now no definition from the studies we have found is flexible to invoke all these domains. The importance of each domain also might depend on the culture and/or country in which treatment burden is used (Tran et al., 2015), and different domains might arise in the future. The majority of the definitions consisted of workloads/tasks and their impact on the patients' well-being. This overlap between them reflected the consistency in defining treatment burden in these studies. However, none of the definitions included patients’ opinions regarding treatment burden by patient participation in the phrasing of the definition. We still lack their input on and evaluation of the definition itself. In the light of the recognized importance of patient-centeredness and shared decision making, the exclusion of any patient input in such a definition of the treatment burden of these patients, is remarkable and should probably be addressed.

However, we think that Boyd's definition is the one in the presently existing literature that covers most of our quality indicators. Though Boyd's definition is not evaluated by patients' participation, we think adding several domains to the definition (such as explicitly naming side effects of medications, and differentiating explicitly between patient's perception and caregiver's perception in the definition) would probably improve it.Tran's definition has also much quality, but misses the differentiation between patient burden and caregiver burden, and also has no input from patient participation.

We think a strength of this study is the thoroughness of the review, with a search expert assisting in assessing and constructing the search strategy. In addition, two independent reviewers screened all the articles in the structured search.

One of the study limitations is the subjectivity of the critical appraisal criteria. As there were no standard, universally accepted criteria available to evaluate the definition of treatment burden. However, we decided that giving insight into the possible lack of domains in the existing definitions, was important, so created our own. This inevitably caused subjectivity, and was also not the main goal of this study.

5. Conclusion

We found that Boyd's definition is the one in the existing literature that covers most of the formulated quality indicators. However, adding some domains to Boyd's definition and differentiating explicitly between patient's perception and caregiver's perception in the definition would in our opinion result in an improved definition for use in the relevant literature. This also should give more proper emphasis to the input of patients' perception and participation into the definition of a burden that should be centered around the patients' experiences.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ahmed Alsadah, Tiny van Merode, Jos Kleijnen: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Riyadh Alshammari: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abu Dabrh A.M., Gallacher K., Boehmer K.R., Hargraves I.G., Mair F.S. Minimally disruptive medicine: the evidence and conceptual progress supporting a new era of healthcare. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2015;45(2):114–117. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2015.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett K., Mercer W., Norbury M., Watt G., Wyke S., Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer K.R., Shippee N.D., Beebe T.J., Montori V.M. Pursuing minimally disruptive medicine: disruption from illness and health care-related demands is correlated with patient capacity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;74:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen K., Scoville E., Shippee N.D., May C.R., Montori V.M. Overwhelmed patients: a videographic analysis of how patients with type 2 diabetes and clinicians articulate and address treatment burden during clinical encounters. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):47–49. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C.M., Wolff J.L., Giovannetti E., Reider L., Weiss C., Xue Q.L., Leff B., Boult C., Hughes T., Rand C. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med. Care. 2014;52(Suppl 3):S118–S125. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a977da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushardt L., Massey B., Simpson W., Ariail C., Simpson N. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2008;3(2):383–389. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demain S., Goncalves A.C., Areia C., Oliveira R., Marcos A.J., Marques A., Parmar R., Hunt K. Living with, managing and minimising treatment burden in long term conditions: a systematic review of qualitative research. PloS One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eton D.T., Ramalho de Oliveira D., Egginton J.S., Ridgeway J.L., Odell L., May C.R., Montori V.M. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2012;3:39–49. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S34681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eton D.T., Ridgeway J.L., Egginton J.S., Tiedje K., Linzer M., Boehm D.H., Poplau S., Ramalho de Oliveira D., Odell L., Montori V.M., May C.R., Anderson R.T. Finalizing a measurement framework for the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2015;6:117–126. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S78955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eton D.T., Yost K.J., Lai J.S., Ridgeway J.L., Egginton J.S., Rosedahl J.K., Linzer M., Boehm D.H., Thakur A., Poplau S., Odell L., Montori V.M., May C.R., Anderson R.T. Development and validation of the Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-management (PETS): a patient-reported measure of treatment burden. Qual. Life Res. 2016;26:489–503. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S.D., Taal M.W. Multimorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease: implications for outcomes and treatment. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016;25(6):465–472. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher K., Jani B., Morrison D., Macdonald S., Blane D., Erwin P., May C.R., Montori V.M., Eton D.T., Smith F., Batty G.D., Mair F.S. Qualitative systematic reviews of treatment burden in stroke, heart failure and diabetes - methodological challenges and solutions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013;13:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher K., Morrison D., Jani B., Macdonald S., May C.R., Montori V.M., Erwin P.J., Batty G.D., Eton D.T., Langhorne P., Mair F.S. Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman W., Mathew R., Carpenter J. Treatment burden and treatment fatigue as barriers to health. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Green S. Wiley-Blackwell; Internet: 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Book Series. [Google Scholar]

- Marengoni A., Angelman S., Melis R., Mangialasche F., Karp A., Garmen A. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011;10:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis S. World Health; 2014. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola R., Karen R., Lakshmi M., Ruth J. University of Stirling; 2010. A Guide to Synthesising Qualitative Research for Researchers Undertaking Health Technology Assessments and Systematic Reviews; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway J.L., Egginton J.S., Tiedje K., Linzer M., Boehm D., Poplau S., de Oliveira D.R., Odell L., Montori V.M., Eton D.T. Factors that lessen the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2014;8:339–351. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S58014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sav A., Kendall E., McMillan S.S., Kelly F., Whitty J.A., King M.A., Wheeler A.J. 'You say treatment, I say hard work': treatment burden among people with chronic illness and their carers in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community. 2013;21(6):665–674. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sav A., King M.A., Whitty J.A., Kendall E., McMillan S.S., Kelly F., Hunter B., Wheeler A.J. Burden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literature. Health Expect. 2013;18(3):312–324. doi: 10.1111/hex.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic Reviews . Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009. CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Tran V., Montori M., Eton T., Baruch D., Falissard B., Ravaud P. Development and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):68. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V., Harrington M., Montori V.M., Barnes C., Wicks P., Ravaud P. Adaptation and validation of the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ) in English using an internet platform. BMC Med. 2014;12:109. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V., Barnes C., Montori V.M., Falissard B., Ravaud P. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2015;13:115. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Akker M., Buntinx F., Knottnerus J.A. Comorbidity or multimorbidity:what’s in a name? Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 1996;2(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.