Capsule summary:

The majority of children with sustained unresponsiveness after extended egg OIT are able to successfully introduce dietary egg. OIT outcome may be predictive of frequency, type (concentrated, baked), and quantity of egg ingested in the long term.

Keywords: Egg allergy, Oral Immunotherapy, Baked egg, Sustained unresponsiveness

To the Editor:

Egg allergy is one of the most common food allergies in childhood and while the majority of egg-allergic children are expected to outgrow their allergy, it can often last into the second decade of life1. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) may represent a potential treatment option for these patients. The ability to introduce egg into the diet after OIT could provide significant benefits to safety, nutrition and quality of life. However, data on the long-term effects of OIT and the subsequent introduction of dietary egg has been limited.

The Consortium for Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) conducted a study of egg powder oral immunotherapy (eOIT) in egg-allergic children ages 5–18 years. Fifty-five subjects were enrolled across the 5 sites of CoFAR with 40 subjects randomized to 2000 mg of eOIT daily and 15 randomized to placebo2. As previously described, 75% of eOIT subjects were desensitized after 22 months of treatment, as defined by passing a 10 gram oral food challenge (OFC) without dose-limiting symptoms while still receiving eOIT 2. 28% of subjects achieved “sustained unresponsiveness” (SU), as defined by passing a 10 gram OFC without dose-limiting symptoms 4–6 weeks after discontinuing eOIT2. Subjects not achieving SU continued on eOIT dosing up to a maximum of 4 years with annual assessments for desensitization and SU. At the conclusion of the eOIT protocol, 20 of 40 subjects (50%) achieved SU, 11 of 40 subjects (28%) were desensitized but failed the SU challenge, and 9 of 40 subjects (23%) were non-desensitized having failed the desensitization challenge3 (Supplemental Figure 1).

After completing eOIT, SU subjects were instructed to introduce dietary egg ad libitum. Non-SU subjects introduced dietary egg on a case by case basis with their local allergists. Based on evidence suggesting a difference in egg allergenicity after extensive heating4, 5, dietary egg was categorized into less allergenic baked egg products such as cakes, cookies and waffles versus lightly cooked concentrated egg products such as scrambled, fried or boiled eggs, French toast, or custards. A 25-question long-term follow-up questionnaire (LFQ) was administered annually for 5 years after completion of the original clinical trial. Questions focused on the consumption of concentrated egg and baked egg products, quantity and frequency of egg ingestion, and safety parameters.

Of the 55 subjects in the original clinical trial, 49 completed at least one LFQ. Participation in the LFQ was strong with a response rate ranging from 76–82% over each of the 5 years, and 43 of 55 subjects (78%) responding at the 5 year time point. There was a differential response rate by study outcome for the 32 of 40 eOIT subjects participating with 19 of 20 SU subjects (95%), 7 of 11 desensitized subjects (64%), and 6 of 9 non-desensitized subjects (67%) responding at Year 5. Eleven of 15 placebo subjects (73%) also participated. The median age of subjects at the initiation of long-term follow-up was 12.7 years.

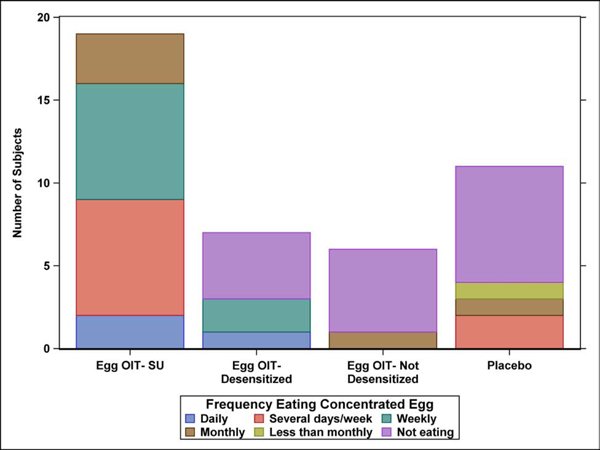

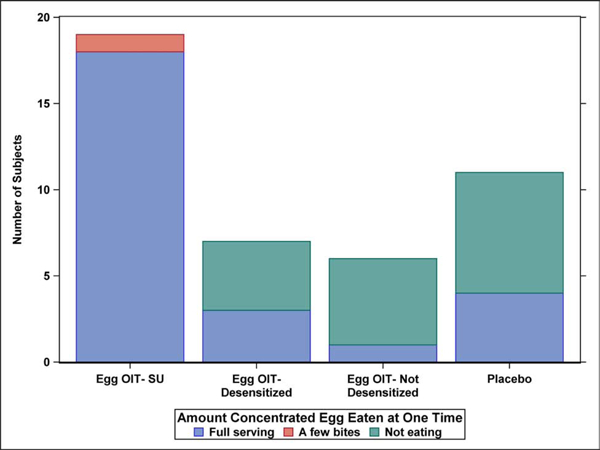

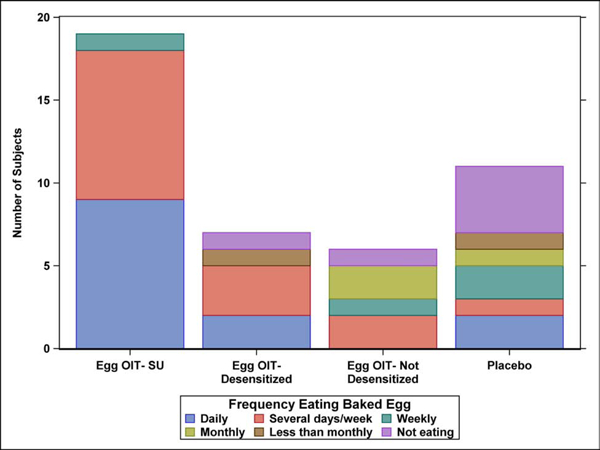

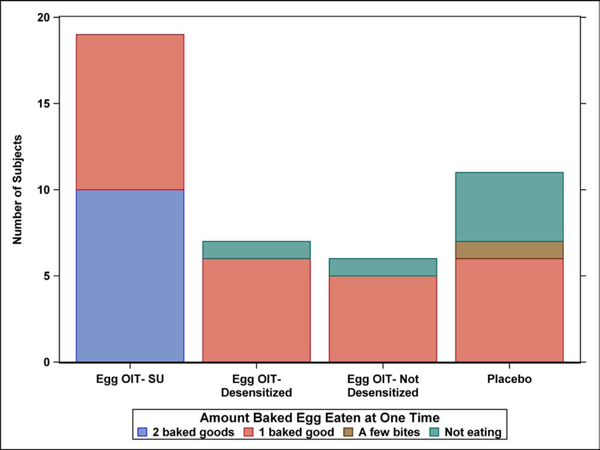

The frequency and amount of concentrated and baked egg regular dietary ingestion at the final Year 5 follow-up is shown by egg consumption outcome after 4 years in the original clinical trial (Figure 1A–D). All 19 SU subjects completing the LFQ reported regular dietary ingestion of both concentrated and baked forms of egg 5 years after completing eOIT. This is compared to 43% of eOIT-desensitized and 17% of eOIT-non-desensitized subjects. Four of 11 placebo subjects reported regular dietary ingestion of all forms of egg. Two of these subjects had participated in separate egg OIT protocols subsequent to the eOIT study, whereas the other 2 subjects may have represented natural resolution. Baked egg only ingestion was reported by 43% of eOIT-desensitized, 67% of eOIT-non-desensitized and 27% of placebo subjects. Only 1 out of 7 eOIT-desensitized and 1 out of 6 eOIT-non-desensitized subjects were fully restricting egg compared to 4 of 11 placebo subjects at the end of follow-up. SU subjects ingested egg products more frequently than eOIT-desensitized and eOIT-non-desensitized subjects with daily or multiple times weekly ingestion reported by 47% for concentrated egg and 95% for baked egg products. SU subjects also ate larger amounts of egg with 95% reporting unlimited ingestion of concentrated and baked egg products. EOIT-desensitized and eOIT-non-desensitized subjects reported smaller quantities of ingestion and the frequency of ingestion in particular for the eOIT-non-sensitized group was less routine.

Figure 1:

Dietary egg consumption at the Year 5 LFQ by egg consumption outcome after 4 years in the original clinical trial. A) Frequency ingesting concentrated egg; B) Amount of concentrated egg ingested per sitting; C) Frequency ingesting baked egg; D) Amount of baked egg ingested per sitting

Symptoms with dietary and accidental concentrated egg ingestion at final follow-up are shown in Table 1. Three of 19 (16%) SU subjects reported symptoms with concentrated egg ingestion. These symptoms were reported to be primarily oral, occurring with <10% of ingestions, and not requiring treatment. One of 4 eOIT-desensitized subjects reported symptoms with most ingestions and the one eOIT-non-desensitized subject ingesting concentrated egg reported rare symptoms. There were 3 subjects who reported epinephrine use [2 eOIT-desensitized (1 at year 2, 1 at year 5), 1 eOIT-non-desensitized at year 1] over the 5 years of followup all occurring after concentrated egg ingestion. At Year 5, no eOIT subjects reported symptoms with any baked egg ingestion.

Table 1.

Symptoms with egg ingestion at year 5 LFQ

| eOIT- SU | eOIT- Desensitized | eOIT- Non-desensitized | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total subjects completing questionnaire – n(%) | 19 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) |

| Ingested any concentrated egg– n(%) | 19 (100.0) | 41 (57.1) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (36.4) |

| Frequency of symptoms– n(%) | ||||

| None | 16 (84.2) | 3 (42.9) | 0 | 3 (27.3) |

| Rarely (<10%) | 3 (15.8) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| Occasionally (10–45%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequently/Regularly (45–80%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most/all (>80%) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

| Treatment– n(%) | ||||

| Epinephrine | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Antihistamines | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Ingested any baked egg– n(%) | 19 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (83.3) | 82 (72.2) |

| Frequency of symptoms– n(%) | ||||

| None | 19 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (63.6) |

| Rarely (<10%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Occasionally (10–45%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequently/Regularly (45–80%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most/all (>80%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

| Treatment– n(%) | ||||

| Epinephrine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antihistamines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

One eOIT-Desensitized subject reported accidental concentrated egg ingestion who did not have it in their diet.

One Placebo subject reported accidental baked egg ingestion who did not have it in their diet.

With growing acceptance of OIT as a future treatment for food allergies, there has been increasing attention on the long-term effects of therapy. Although there have been reports of SU after OIT2, 6, definitive evidence of tolerance induction has been lacking. In lieu of this, the ability to introduce the allergenic food into the diet after OIT would have meaningful nutritional and quality of life effects while also providing regular exposure to the antigen to potentially maintain the desensitized state. Furthermore, recent data has suggested that regular ingestion of baked egg products may possibly hasten the natural resolution of egg allergy7. In this long-term observational follow-up after eOIT, 30 of the 32 eOIT subjects completing the LFQ 5 years after eOIT completion were able to introduce baked egg and 23 eOIT subjects were further able to introduce concentrated egg into the diet. Only 2 eOIT subjects were fully restricting egg 5 years after completion of eOIT compared to 4 of 11 placebo subjects. Although 4–6 weeks of SU would not be adequate to define tolerance, subjects achieving SU after eOIT seemed to represent a different phenotype as these subjects were ingesting both concentrated and baked egg in larger quantities and more frequently than those not achieving SU. It would be important to investigate whether this effect is also seen with other allergens such as milk and peanut. A limitation of these results is that the eOIT protocol lacked an entry food challenge to egg powder or baked egg. In addition, the differential response rates across eOIT outcomes could have had an effect on the end results. Finally, 4 of 11 placebo subjects were ingesting dietary egg at the end of the study. The 2 subjects who participated in additional clinical trials completed their individual egg OIT protocols and safely ingested 7444 mg and 4000 mg of egg protein respectively. While these 2 subjects clearly did not represent the pure placebo effect, their data were included as part of a conservative intent-to-treat analysis and were not thought to alter the comparison between the SU, desensitized and non-desensitized groups. The other 2 placebo subjects likely represented natural resolution which could have occurred in some eOIT subjects as well. In summary, treatment with a 4 year eOIT protocol results in successful introduction of egg in the majority of egg-allergic children lasting up to 5 years after completion of therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: NIH-NIAID U19AI066738 and U01AI066560. The project was also supported by Grant Numbers UL1 RR-025780 (National Jewish), UL1 TR-000067 (Mount Sinai), UL1 TR-000039 (Arkansas), UL1 TR-000083 (U North Carolina) and UL1 TR-000424 (Johns Hopkins) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Disclosure statement:

EH Kim reports consultancy with Aimmune therapeutics, DBV technologies, AllerGenis and Allakos; clinical medical advisory board membership with DBV technologies. Grant funding has been received from the NIH-NIAID, NIH-NCCIH, FARE and the Wallace Research Foundation. SM Jones is on the research advisory board for FARE; has consultant arrangements with Aimmune Therapeutics and Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.; has received grants from Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Astellas, Regeneron, Genentech, FARE, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Immune Tolerance Network and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Consortium for Food Allergy Research; and has performed CSR review/preparation for DBV Technologies on behalf of EMMES Corporation, LLC. AW Burks reports minority stock holder in Allertein, Mastcell pharmaceuticals; advisory board membership with Aimmune therapeutics, Consortia TX Inc, Prota therapeutics; consultancy for DBV technologies, N-fold; royalties with UpToDate; speaking fees with Gordon Research Conferences, Pediatric Allergy and Asthma Meetings; sponsored research with FARE, NIH. RA Wood reports royalty payments from UpToDate and grants to his institution from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV, Astellas, Sanofi and from HAL Allergy.

SH Sicherer reports grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, personal fees from UpToDate, personal fees from Johns Hopkins University Press, outside the submitted work.

DYM Leung receives grant support to his institution from NIAID, NIAMS and is Chairman of the DSMC for Aimmune.

AK Henning is employed by Emmes which received support for this work via grant from DAIT/NIAID/NIH through Johns Hopkins University.

RW Lindblad is employed by Emmes which received support for this work via grant from DAIT/NIAID/NIH through Johns Hopkins University.

P Dawson is employed by Emmes which received support for this work via grant from DAIT/NIAID/NIH through Johns Hopkins University.

C Keet reports grant funding from the NIH, royalties from Up-To-Date, and membership on the Board of the American Board of Allergy and Immunology.

AM Scurlock reports membership on the DBV Clinical Medical Advisory Board and FARE Clinical Network and has received NIH-NIAID funding, as well as clinical trials funding from Aimmune, Astellas, DBV, Regeneron.

HA Sampson reports being a part-time employee of DBV Technologies; receiving consultant fees from N-Fold LLC, and royalties for various textbooks; holding stock options in DBV Technologies and N-FOLD; and receiving grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Savage JH, Matsui EC, Skripak JM, Wood RA. The natural history of egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, Fleischer DM, Sicherer SH, Lindblad RW, et al. Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones SM, Burks AW, Keet C, Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Wood RA, et al. Long-term treatment with egg oral immunotherapy enhances sustained unresponsiveness that persists after cessation of therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1117–27 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemon-Mule H, Sampson HA, Sicherer SH, Shreffler WG, Noone S, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Immunologic changes in children with egg allergy ingesting extensively heated egg. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(5):977–83 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miceli Sopo S, Greco M, Cuomo B, Bianchi A, Liotti L, Monaco S, et al. Matrix effect on baked egg tolerance in children with IgE-mediated hen’s egg allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(5):465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, Steele PH, Kamilaris J, Berglund JP, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard SA, Sampson HA, Sicherer SH, Noone S, Moshier EL, Godbold J, et al. Dietary baked egg accelerates resolution of egg allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):473–80 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.