Abstract

Bioinoculants are eco-friendly microorganisms having a variety of products commonly utilized for improving the potential of soil and providing the nutrient requirements to the host plant. The usage of chemical fertilizers is not beneficial because it affects the soil microbial communities on large scale. The toxicity of chemical fertilizer decreases the fertility of soil and causes microbial disruption. Bioinoculants that are used as PGPR play an important role in the enhancement of crop production and beneficial for both producers and consumers economically by protecting the soil during unfavourable conditions. The utilization of PGPR in the bioinoculant form imparts successfully sustain agricultural yield production and such formulated products contain living microbial cells of bioinoculants that also helps in seed treatment and enhances the mobilization process of nutrients by the low-cost process. This review mainly focuses on different bioinoculant formulations related to its recent approaches such as metabolite formulations, liquid formulations, solid carrier-based formulations and synthetic polymer-based formulations. This review also gives an overview of some aspects of the bioinoculant efficiency and their appropriate formulation, production and storage condition of microbial cells.

Keywords: Bioinoculants, Bioencapsulation, Metabolite, Soil microbial communities, Polymeric substance

Introduction

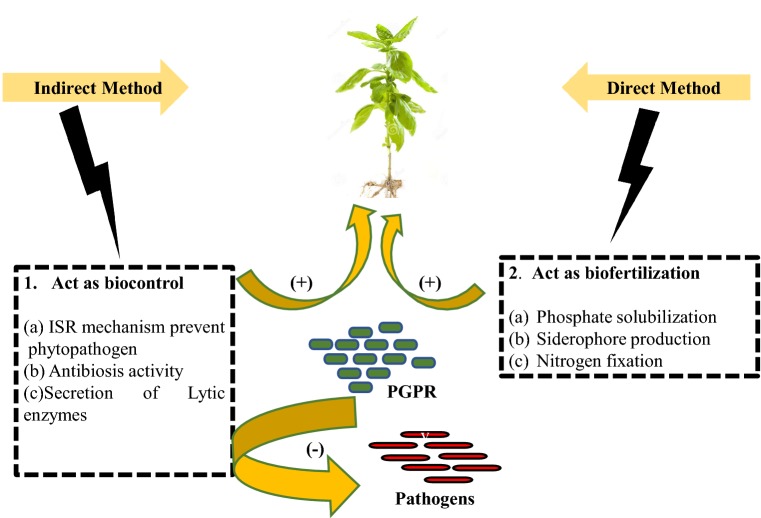

Bioinoculants are the beneficial soil amendments that use microbes for promoting plant growth and development. They contain dormant or live cells of the efficient strain of nitrogen-fixing, Hydrogen cyanide and siderophore producing microorganisms (Puri and Padda 2017; Lalitha 2017). The interactions between soil-borne microbes and the roots of higher plants play a significant role in plant development and growth by converting unavailable nutritional elements into available form (Imam et al. 2017). Bioinoculants also help in seed treatment by forming a uniform coating of inoculant over seeds, bioremediation and induce systemic acquired resistance (Dangi et al. 2019; Ma 2019). Several plant growth-promoting microbial strains such as Azospirillum, Rhizobium, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, mycorrhiza, Trichoderma and yeast have been identified that are used as bioinoculants (Aremu et al. 2017; Tahir et al. 2017). Plants take benefit from microbes in various ways 1. By PGPR (Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria) that act as bioinoculants 2. By phytostimulation (phytohormones expressed by microbes like Azospirillum) that directly promote the growth of plants. 3 By act as biological control agents and also in phytoremediation process (like Bacillus cereus, Trichoderma and Pseudomonas) that protect plants against harmful organisms and heavy metals (Meena et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2020). Schematic descriptive mechanism of several traits shown by PGPR depicted in Fig. 1. For their formulation, many recent approaches such as metabolite formulations, liquid formulations, solid carrier-based formulations, and synthetic polymer-based formulations are used (Arora et al. 2017; Gopi et al. 2019). Many research studies have reported that the formation of flocks and aggregates can be efficiently utilized for the development of formulations for various agricultural practices. Aggregation of microbial cells is induced by nutrient-limited conditions and by various physical and chemical factors. For bioinoculant preparation, mainly Fed-Batch cultivation technique is used, and in this cultivation, mostly high-density culture is used like Pseudomonas spp. (Mutturi et al. 2017). Microbial inoculants can also be applied as biofertilizers such as Frankia, Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, Dyadobacter etc. using liquid or solid base nutrient medium (Suyal et al. 2016). In the bioformulation process, harmful components are destroyed by the activity of microbial community.

Fig. 1.

Schematic descriptive mechanism of several traits shown by PGPR that acts as bioinoculants. Various mechanisms can be studied by (1) Bio control of various pathogens (2) Act as Biofertilization. As a Biocontrol process: (a) Induction of Systemic Resistance (ISR) mechanism by PGPR, (b) Antibiosis activity and (c) Secretion of lytic enzymes. Biofertilization involves (a) Phosphate solubilization, (b) Siderophore production and (c) Nitrogen Fixation

Contemporary techniques for improving formulations of bioinoculants

The bioinoculant formulation is the uniform mixture of selected beneficial strain with a suitable carrier that can provide stabilization and protection of strain during transport and storage. The carrier is the vehicle of living latent microbes that provides protection and supportive niche to the microbial community. A good bioformulation should be effective, non-polluting, readily biodegradable with high water retention capacity and sufficient shelf life (Malusa et al. 2012; Sahu et al. 2018). The formulation process improves the efficiency and shelf life of biofertilizers. Sometimes, the formulation contains some cell protectants with desired microorganisms that increase the shelf life of spores during adverse conditions (Bhattacharyya et al. 2020). Different types of formulation are formed on the basis of their efficiency and survival rate.

Solid formulation

In this preparation, the beneficial strain is mixed with a solid carrier. It is used for transporting strain from the laboratory to fields. Mainly peat, powder and granules are used for this formulation. It provides a protective and nutritive environment to those microbes that form micro-colonies. Peat should be adaptive, easily sterilized, nontoxic with high water holding capacity (Ceglie et al. 2015). After the process of peat drying, it is passed through 250 µm sieves and mix with proper strain. For bacterial multiplication, peat is incubated at a specific temperature and this step is called curing. For ectomycorrhizal and AMF (arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi) inoculants, mainly peat is used (Aini et al. 2019; Pathak et al. 2017). On glucose medium, ectomycorrhiza can quickly grow and can produce sporophore that is used for inoculation in the field. To prevent the growth of contaminants and pathogens, pure mycelia culture is used as formulation using 10–15% peat and vermiculite as a carrier with glucose and salt medium. This type of formulation increases the chelating process through the production of fulvic acid. Before sowing, inoculated peat is applied on the surface of seeds and this process is done with the help of machines viz. cement mixers, large dough, and mechanical tumbling machines, etc. The main drawback of using peat is its variability in its composition and quality. Sometimes toxic compounds are also released from peat during the process of sterilization that can affect the survival rate and growth of microbes (Malusa et al. 2012). Recently, granules have been used instead of peat since granules have some advantages over peat. Like peat, granules are coated by the living cells of microbes and they are made of calcite, marble and silica grains. The granules are much better and have many advantages over peat. Granules are easier to handle, less dusty, easy transport and for storage. During granule formulation, inoculants are placed on the furrow nearby seed surface to ease the lateral-root interactions. Some experimental study showed that the application of granular inoculants does not exhibit better nitrogen fixation. In contrast, some research showed that formulation by granules is superior to liquid and peat inoculants in terms of total biomass, nitrogen fixation, nitrogen accumulation and in nodule number (Zaidi et al. 2017). The major advantage of granular inoculants is notable under stress conditions such as moisture stress, soil acidity and wet soil due to its high nitrogen fixation and nodule formation capability in stress conditions. The techniques and materials used for the carrier formulation are described in Table 1. Other than peat, charcoal-based carrier, i.e., biochar can also apply as a reliable carrier for bioinoculant formulation. Biochar helps in the survival rate of bioinoculant and it is eco-friendly and free from toxic elements. The main beneficial effect of using charcoal is that it can be stored without sterilization due to its low water content. It is free from waxy materials without any blending problem that provides an efficient plant health assurance for crop field.

Table 1.

Carrier formulation materials and techniques for microbial inoculant

| Microbe | Plant | Formulation material | Technique | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | Lettuce | Alginate | Cross-linking | Young et al. (2006) |

| Pseudomonas putida | Lettuce | Humic acid | Cross-linking | Rekha et al. (2007) |

| Pseudomonas corrugate | Triticum aestivum | Alginate | Cross-linking | Trivedi and Pandey (2008) |

| A. brasilense | Legume trees | Alginate | Cross-linking | Bashan et al. (2014) |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | Alfalfa | Canola oil | Emulsion | John et al. (2013) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Cotton seeds | Alginate | Cross-linking | Wu et al. (2014) |

| A. brasilense | Sorghum bicolour | Alginate | Cross-linking | Trejo et al. (2012) |

Liquid formulation

The liquid formulation is the microbial preparation that contains those beneficial microbes, which have the capability of solubilizing, fixing or mobilizing essential plant nutrients by biological activities (Bahadur et al. 2016). Potash mobilizing microbes, phosphate mobilizing microbes, nitrogen-fixing microbes (NFM) and many other groups of microbes are used in the liquid formulation (Surendra and Baby 2016). Recently, researchers concentrate on mobilization and solubilization of micronutrients by the activity of microbes such as manganese, sulfur and zinc solubilizing bacteria. The liquid formulation is the latest and promising technology over conventional carrier-based formulation due to its beneficial effects. The carrier-based formulation has a short shelf life, i.e., 2–3 months, and it cannot retain throughout the crop cycle. To overcome this problem, the liquid formulation is used that provides the facility with prolonging survival rate of the selected strain throughout the crop cycle. Another advantage of using this formulation is the temperature and stress tolerance that is not tolerated by carrier-based bioinoculants. During this formulation, proper sterilization can be done by which contamination can be controlled, but in carrier-based formulation, bulk sterilization is impossible. It enhances the viability and survival of the strain by retaining high moisture capacity for more extended periods. It contains a desirable strain with some protectants for improving the shelf life up to 19–25 months during the stressful condition (Chandra et al. 2018). Azospirillum is a plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, free-living and microaerophilic which is mainly used for the formation of the liquid formulation. Along with Azospirillum other phosphate mobilizing strains belonging to genera Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Penicillium and Aspergillus are also used. It is reported that the storage of 108 cells/ml up to 8–10 months can be done by modifying Azospirillum with Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), glycerol and trehalose in nitrogen-free bromothymol blue meat broth. It has been reported that due to high water-retaining capacity, PVP protect microbes during the toxic and stressed condition. The storage of endospores (log10 8.21), CFU/ml) up to 4–6 months using B. megaterium with glucose, PVP and glycerol can be used as a liquid formulation process. Formulation of Azospirillum with PVP had a longer shelf life when compared it without PVP amendment. PVP supplementation reported greater microbial population i.e. (10 8 CFU/ml). A population of Azospirillum (1.66 × 108 CFU/ml) in trehalose (16 mM) and phosphate solubilizing strain (3.66 × 108 CFU/ml) in the PVP (3%) is used for this formulation (Surendra and Baby 2016). Therefore, it was concluded that both PVP (3%) and trihalose (16 mM) are highly suitable bioinoculants that enhance the shelf life of PSB (Phosphate solubilizing bacteria) and Azospirillum sp., respectively, up to 10 months with a highest microbial population (108 CFU/ml) at room temperature.

Metabolite formulation

Metabolite formulation contains those microbial metabolites that help in providing bioregulators, essential nutrients and fighting against phytopathogens. For metabolite formulation strains belonging to genera Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma and some mycorrhizal fungi strains are used. To overcome the drawbacks of cell-based formulation, metabolite bioformulation has been recently developed (Tewari and Arora 2016). It is reported that flavonoids biomolecules with the rhizobial strain increase nitrogen fixation and nodulation under stress condition. Rhizobial species that are associated with leguminous host plants secrete lipochitooligosachharide biomolecules. It was reported that lipochitooligosachharide help in symbiosis in rhizobial deficient fields. For both non-leguminous and leguminous crop yield Novozymes has been significantly increased through lipochitooligosachharide promoter and flavonoids. Like nod factors, Myc factors are also released by mycorrhizal fungi that help in symbiosis and activate the pathway of signal transduction (Maillet et al. 2011). Recently, it has been developed that exopolysaccharide (EPS) released by plant growth-promoting bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Rhizobia enhances root colonization, biofilm formation and nodulation under toxic and stress condition (Wang et al. 2019). Exopolysaccharide released by Rhizobium played a crucial role in microbial protection. Bioformulation supplement with EPS help in protecting strains from osmotic shock, extreme pH, radiations, desiccation, predator and toxic substances. It has been studied that supplementation of the precursor, such as tryptophan, enhanced IAA production and increases grain yield, plant biomass, and root hair formation. PGPR amended with l-methionine (precursor of ethylene) that acts as chief metabolite resulted in increased growth. It has been reported that nutrients such as starch wastewater, amino acids and molasses were used as useful amendments. These amendments can enhance the shelf life and survivability of beneficial strain in the harsh soil environment (Timmusk et al. 2014). It has been reported that PSB (Phosphate solubilizing bacteria) also releases biosurfactants such as antimicrobial, emulsifiers, wetting agents, antiviral and anti-insecticidal activities (Arora and Mishra 2016). Biosurfactants in liquid bioinoculants mainly used for the spraying process in the aerial parts of the plant. Attractants and phagostimulatory like pheromones, glutamate, sucrose and molasses secreted by liquid bioinoculants and attract phytopathogens and kill them. Strains like fluorescent Pseudomonas produce antimicrobials such as pyrrolnitrin, fanzines, omission A and diacetylphloroglucinol. In a similar way Bacillus spp. also studied for the production of antibiotics. It is also reported that many anti-phytopathogenic activities shown by secondary metabolites that are produced by Bacillus and Pseudomonas (Perez-Garcia et al. 2011) The major drawback of using this formulation is its high cost and its production on a large scale. The future metabolite formulation also used as a combination of the plant growth-promoting strain with additives and carrier that enhances the microbial activity. Primary and secondary metabolites are also present in the form of attractants, adjuvants and stimulants in this formulation.

Polymeric formulation

For polymeric formulation, mainly alginate is beads used. It is a natural polymeric substance which is made up of l-glucuronic acid and d-mannuronic acid which are derived from Macrocystis pyrifera (brown algae). It has been studied that it is also produced from Sargassum sinicola (macroalga) (Yabur et al. 2007). Recently, it has been considered that various bacterial strains like Azotobacter and Pseudomonas are used for this type of formulation. Alginate beads are of two types i.e., microbeads and macrobeads with diameter 2–3 mm and 50–200 µm which can trap 109–110 CFUg−1 (colony forming unit per gram). This formulation increases the stability of mushroom cultivation, bacterial chemotaxis and also plasmid in the host cell. For alginate matrixes, AMF is used for trapping procedure. Recently, many techniques developed for polymeric formulation using encapsulation of latent cell in the gel matrix for various applications. Gel matrix has the capability for prolonging the shelf life of usable strain under biotic and abiotic stressful conditions. Nowadays, during the encapsulation process, nutritional additives are also used that provides favorable growth under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions (Schoebitz and Belchi 2016). First of all, this technique was used for Pseudomonas fluorescens, A.brasilense and Aspergillus (filamentous fungi) strains during formulation (Singh et al. 2011). It was reported that addition of useful nutrients such as skimmed milk can enhance the viability of the strain in the presence of glycerol. It was evaluated that chitin filled beads have the capability of porosity than starch filled encapsulated cells. Recently, it was proved that glycerol-alginate beads have much better survival rate under UV radiation (Zohar-Perez et al. 2002). It has been proposed that the growth and cell viability of Sinorhizobium meliloti can be increased using soy oil and alginate to108 CFU/ml after 10 weeks of storage (Malusa et al. 2012). At room temperature, the formation of alginate beads is a multi-step and complicated procedure (de-Bashan et al. 2012). It was reported that alginate is non toxic in nature, biodegradable and releases gradually in the field.

Potential of macro and micro alginate beads

In the earlier techniques, mainly mycorrhiza fungi (Streptomycetes sp.) and bacterial strain were used in the macro-alginate beads (2–5 mm) using kaolin–alginate formulation. Therefore, for increases the survival rate of Streptomycetes sp. talcum and starch powder was added and formulated for 15 weeks (Sabaratnam and Traquair, 2002). It was reported that survival and storage rate of Bacillus subtilis were increased for six months by adding it with humic acid (Young et al. 2006). Encapsulation feasibility improved by the addition of humic acid to alginate. Encapsulated strain such as Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas putida both help in increasing the survival rate in beads during storage (Rekha et al. 2007). Trivedi reported that various alginate formulations using Pseudomonas corrugate and Bacillus subtilis were found better and superior results over charcoal-based and liquid bioinoculants (Trivedi et al. 2005). A combination of C. sorokiniana, Chlorella vulgaris (microalgae) and Azospirillum brasilense were developed to remove the nitrogen and phosphorus from municipal wastewater (de-Bashan et al. 2012). It was reported that co-immobilization of the two microbes could provide better results than a single microalga (Covarrubias et al. 2012). It improves the growth of sorghum by immobilization in eroded soil (Lopez et al. 2013; Trejo et al. 2012). To overcome the difficulties of the macro alginate beads concept of micro alginate beads developed (60–200 µm in diameter). The formation of alginate microbeads is an easy and straight forward process by adding bacterial rich medium (Bashan et al. 2002). During spraying, droplets mixed with CaCl2 to solidify the microbeads up to 150 to 200 µm. Other benefits of using micro alginate beads were included as (1) use for various transplanted desert during reforestation (de-Bashan et al. 2012). (2) Encapsulated Pseudomonas fluorescens enhances the survival of microbes by the colonization of Beta vulgaris and production of antifungal metabolite 2,4-diacetyl phloroglucinol after prolonged storage of 14 months. (3) Used also for biological control against Solenopsis invicta (red fire ant) using micro alginate beads that contain (Beauveria bassiana) entomopathogenic fungus coated with peanut oil (Bextine and Thorvilson 2002). In formulation process, Biological control microbial species act differently according to their mode of action. In most of cases they produce different types of metabolites that are pathogen specific and non toxic to the environment. It is reported that various type of compounds released by biological control microbial species, but they show inactive signaling mechanism with the environment. These types of species release some specific type of inducers that are recognized by specific receptors of plant which are irrelevant to the environment. Such kind of metabolites is natural in behavior and play like a symbiotic type role between plants and microbial cells. The majoring potential of alginate beads is to encapsulate the microbes, exogenous genes, seeds and agricultural chemicals. These immobilized alginate beads are easy to produce and handle during agricultural practices. Yet these beads are small in size but a large number of bacteria are encapsulated in these beads. They show a positive effect on the growth of host plant by slow release of microbes in the soil with a desired period of time (Zago et al. 2019). It was reported that the storage and viability process of alginate beads increases up to 90 days when developed by 3% sodium alginate with Azospirillum brasilense.

They provide a suitable micro environment for the microbial cells and the host plant.

Bioencapsulation and co-inoculation

In the capsulation process, living microbial cells entrapped in polymeric matrix substances for enhancing the survival of microbes. Bioencapsulation of usable strain in a polymeric matrix is called immobilization. During the co-immobilization process, more than one type of microbe is used and applied in the field of environmental and agricultural technology. Various techniques for encapsulation and their significance are described in Table 2. It is widely used in pharmaceutical, food, agriculture and other industries for various purposes to attain a protective structure. Bioencapsulation of microbial inoculants involves three steps: The first step comprises with the absorption of usable ingredients into a matrix (solid or liquid), the second step consists in spraying a solution on solid particles and making dispersion, and the third and last step comprises stabilization by chemical-physical processes (conservation and gelatin) and chemical process of polymerization. Bioencapsulation tends to stabilize the viability and stability of microbial cells for storage, protection during dehydration and handling of cultures (Kim et al. 2012). Bioencapsulation also protects microbes under biotic and abiotic stress conditions (Kim et al. 2012). Biological activities of soil microflora have a direct relationship with the degradation rate of the encapsulated matrix. Microbial agents are encapsulated for their use as plant growth-promoting agents or biocontrol agents. Encapsulated cells are dried capsules and stored at room temperature for a prolonged period that provides a favorable environment for microbial cells. Fermentation produces an immobilized microbe-synthetic matrix and this formulation used for various purposes like the formation of amino acids, organic acids, enzymes, vitamins and in bioremediation (Imam et al. 2013; Bashan et al. 2014). The principal role of the encapsulated formulation of the microbial cell is to provide short-term shelter in the soil environment under stressful condition during rhizospheric colonization. The primary disadvantage of the encapsulation process is due to its high cost and hard practices during bead formation. The use of Co-inoculation or multistrain inoculation technique proved a benefit over single strain due to increased yield production and decreased its dependency on the exogenous nitrogen supply (Bashan et al. 2014). Over three years use of multi-strain bioinoculant has extensively increased rice yield in field trials. Co-inoculation act as synergistically for another bacterium to enhance their performance by removing inhibitory products and by stimulating a physical or biochemical reaction. The absorption process of nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients is improved by co-inoculation (Bashan et al. 2014). The major side effect of co-inoculation is the different food requirement in in-vitro condition of different microorganisms (Reddy and Saravanan 2013). It has been shown that coinoculation of rhizobium with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria help in preventing pathogenic disease and increases nodulation capability (Chaudhary and Shukla 2019; Frederix et al. 2014).

Table 2.

Techniques for bioencapsulation and their significance

| Techniques | Core | Water soluble | Processing time | Applications | Advantage | Disadvantage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spray drying | Beads | Yes | 10–30 s | Thermal resistance cells | Fast and inexpensive | Dust and high temperature | Schoebitz et al. (2016) |

| Fluidized bed | Capsules | Yes | 10 min–1 h | Irregular particles | Flexible and inexpensive | Coating fine particles | Zhang et al. (2002) |

| Extrusion | Either beads or capsule | Yes | 10 min–1 h | Vitamins and enzymes | Biocompatible | Diffusion | Li et al. (2017) |

| Molecular inclusion | Beads | Poorly | 5–10 min | Flavor | Selective trapping | Low loading | Lakey et al. (2017) |

| Interfacial polymerization | Capsules | No | 10 min–2 h | Hydrophobic Drops | Large batches well-developed process | Core wetability | Singh (2018) |

| Conservation | Capsules | No | 12–16 min | Hydrophobic drops | Impermeable to hydrophobic molecules | Aggregation and core wet ability | Berninger et al. (2018) |

| Liposomes | Capsules | No | 5–10 min | Capsules | Biocompatible and tiny particles | Thin walls and low loading | Kim et al. (2012) |

Understanding the impact of all formulation techniques and its challenges

As discussed above, the liquid bioformulation technique is the most promising and recent technology over conventional based formulation due to its more valuable and beneficial effects. The other type of formulation has a very short shelf life, i.e., 4–5 months. To overcome this vital problem, the liquid formulation technique is the best bioformulation method because it provides the facility with prolonging the survival rate of the selected strain during the crop cycle. Another advantage of using this formulation is the temperature and stress tolerance that is not tolerated by carrier-based bioinoculants. Apart from this, there are a lot of challenges that are faced during the usage of bioformulation. In developing countries, a large number of bioinoculants effectively used for agricultural purposes. All through, the chemical fertilizers are not expensive in developed countries so the use of bioinoculants is negligible for organic agriculture (Timmusk et al. 2017). Due to eco-friendly nature, microbial niche increases soil fertility, lightens the abiotic stress and has various advantages as compare to synthetic fertilizers (Bharti et al. 2016). On the other hand, more usage of bioinoculants will require a large number of problems that should be addressed. The main critical problem with the prevalent use of bioinoculants is the commercialization of their products (Warra and Prasad 2020). Chemical fertilizers are used as a widespread spectrum that greatly affects the microflora. Additionally, there is a big challenge in the registration process of microbial products. In the European countries, there are several restrictions regarding bioinoculants or biofertilizers (Rani and Kumar 2019). The flourishing commercialization of bioinoculants mainly depends upon various factors like a good research (using the best strain for the formulation), the performance of farmers (with reference to bioinoculants) and the private market sector (sustainable and economically market and large scale-up production) (Mahanty et al. 2017). A well demonstrative trial for the farmers can give them better confidence for the efficient use of biofertilizers.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Bioinoculants are much effective and eco-friendly microorganisms that help in the improvement of soil under adverse conditions. By the formulation techniques, the indigenous microbial community can change the structure and composition of the soil. As a result of formulation, a positive and synergistic effect enhances the shoot and root growth. They help in the retention of soil fertility and protect the environment during adverse conditions. The techniques that are used to build up the soil microbial communities affect the interactions of microbes. Use of bioinoculant is sustainable because it benefits the producers and consumers economically by protecting the soil during unfavorable conditions (Singh et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2016). By the advancement of DNA sequencing techniques, more emphasize will be shed on the metabolic capabilities of soil microbial communities and their significance in the soil ecosystem (Kumar et al. 2017). The central perspective is focused on how to isolate, their colonization ability, formulation and know their mechanism of interaction of the domestic growth-promoting bacteria from an undesirable stress condition that could be used as bioinoculants (Kaushal and Wani 2015). Microbes that are used as bioinoculants promote not only growth but also enhance resistance to biotic and abiotic stress and pathogens (Dangi et al. 2018; Imam et al. 2016). There are still lots of potential of using innovative technologies towards improving the capability of bioinoculant but it needs better integration of ideas and utilizing them for sustainable agriculture, nevertheless, the present review can guide towards utilizing these innovative steps in the bioinoculant formulation.

Acknowledgements

The author, TC acknowledges Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak, India for University Research Scholarship (URS). PS acknowledges Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, Govt. of India, FIST grant (Grant no. 1196 SR/FST/LS-I/ 2017/4) and Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (Grant no. BT/PR27437/BCE/8/1433/2018).

Author contributions

TC wrote the manuscript with contributions from MD, AKS and GG. The manuscript was edited by PS, RG, AP.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The Authors don’t have any conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This review article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Aini N, Yamika WSD, Ulum B. Effect of nutrient concentration, PGPR and AMF on plant growth, yield, and nutrient uptake of hydroponic lettuce. Int J Agric Biol. 2019;21(1):175–183. doi: 10.17957/IJAB/15.0879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z, Abul-Faraj A, Li L, Ghosh N, Piatek M, Mahjoub A, et al. Efficient virus-mediated genome editing in plants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1288–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MM, Landes X, Xiang W, Anyshchenko A, Falhof J, Østerberg JT, et al. Feasibility of new breeding techniques for organic farming. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aremu BR, Alori ET, Kutu RF, Babalola OO. Potentials of microbial inoculants in soil productivity: an outlook on African legumes. In: Panpatte DG, Jhala YK, Vyas RVS, editors. Microorganisms for green revolution HN. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Arora NK, Mishra J. Prospecting the roles of metabolites and additives in future bioformulations for sustainable agriculture. Appl Soil Ecol. 2016;107:405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arora NK, Verma M, Mishra J. Rhizobial bioformulations: past, present and future. In: Mehnaz S, editor. Rhizotrophs: plant growth promotion to bioremediation. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur I, Maurya BR, Kumar A, Meena VS, Raghuwanshi R. Towards the soil sustainability and potassium-solubilizing microorganisms. In: Meena VS, Maurya BR, Verma JP, Meena RS, editors. Potassium solubilizing microorganisms for sustainable agriculture. New Delhi: Springer; 2016. pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu MC, Kavas M, Gürel S, Gurel E. The use of microorganisms for gene transfer and crop improvement. In: Prasad R, Gill SS, Tuteja N, editors. Crop improvement through microbial biotechnology pp 1–25. Berlin: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y, de-Bashan LE, Prabhu SR, Hernandez JP. Advances in plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculant technology: formulations and practical perspectives (1998–2013) Plant Soil. 2014;378(1–2):1–33. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1956-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bashan Y, Hernandez JP, Leyva LA, Bacilio M. Alginate microbeads as inoculant carriers for plant growth-promoting bacteria. Biol Fert Soils. 2002;35(5):359–368. doi: 10.1007/s00374-002-0481-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger T, Gonzalez Lopez O, Bejarano A, Preininger C, Sessitsch A. Maintenance and assessment of cell viability in formulation of non-sporulating bacterial inoculants. Microb biotechnol. 2018;11(2):277–301. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bextine BR, Thorvilson HG. Field applications of bait-formulated Beauveria bassiana alginate pellets for biological control of the red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Environ entomol. 2002;31(4):746–752. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-31.4.746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti N, Pandey SS, Barnawal D, Patel VK, Kalra A. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Dietzia natronolimnaea modulates the expression of stress responsive genes providing protection of wheat from salinity stress. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/srep34768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya C, Roy R, Tribedi P, Ghosh A, Ghosh A (2020) Biofer-tilizers as substitute to commercial agrochemicals. In: Majeti N, Vara P (eds) Agrochemicals detection, treatment and remediation butterworth-heinemann, pp 263–290. 10.1016/B978-0-08-103017-2.00011-8

- Ceglie FG, Bustamante MA, Amara MB, Tittarelli F. The challenge of peat substitution in organic seedling production: optimization of growing media formulation through mixture design and response surface analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Barh A, Sharma IP. Plant growth promoting bacteria: a gateway to sustainable agriculture. Microbial Biotechnol Environ Monitor Cleanup. 2018;2018:318–338. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-3126-5.ch020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary T, Shukla P. Bioinoculants for bioremediation applications and disease resistance: innovative perspectives. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59(2):129–136. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00783-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias SA, Bashan LE, Moreno M, Bashan Y. Alginate beads provide a beneficial physical barrier against native microorganisms in wastewater treated with immobilized bacteria and microalgae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(6):2669–2680. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangi AK, Sharma B, Hill RT, Shukla P. Bioremediation through microbes: systems biology and metabolic engineering approach. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2019;39(1):79–98. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2018.1500997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangi AK, Sharma B, Khangwal I, Shukla P. Combinatorial interactions of biotic and abiotic stresses in plants and their molecular mechanisms: systems biology approach. Mol Biotechnol. 2018;60(8):636–650. doi: 10.1007/s12033-018-0100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de-Bashan LE, Hernandez JP, Bashan Y. The potential contribution of plant growth-promoting bacteria to reduce environmental degradation—a comprehensive evaluation. Appl Soil Ecol. 2012;61:171–189. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frederix M, Edwards A, Swiderska A. Mutation of praR in Rhizobium leguminosarum enhances root biofilms, improving nodulation competitiveness by increased expression of attachment proteins. Mol microbial. 2014;93(3):464–478. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopi GK, Meenakumari KS, Nysanth NS, Subha P. An optimized standard liquid carrier formulation for extended shelf-life of plant growth promoting bacteria. Rhizosphere. 2019;11:100160. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2019.100160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imam J, Shukla P, Prasad Mandal N, Variar M. Microbial interactions in plants: perspectives and applications of proteomics. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(9):956–965. doi: 10.2174/1389203718666161122103731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imam J, Singh PK, Shukla P. Plant microbe interactions in post genomic era: perspectives and applications. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1488. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imam J, Variar M, Shukla P. Role of enzymes and proteins in plant-microbe interaction: a study of M oryzae versus rice. In: Shukla P, Pletschke BI, editors. Advances in enzyme biotechnology pp 137–145. New Delhi: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- John RP, Tyagi RD, Brar SK, Prevost D, Surampalli RY. Effect of emulsion formulation of Sinorhizobium meliloti and pre-inoculated seeds on alfalfa nodulation and growth: a pouch study. J Plant Nutr. 2013;36(2):231–242. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2012.739243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal M, Wani SP. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria: drought stress alleviators to ameliorate crop production in drylands. Ann Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13213-015-1112-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Glick BR, Bashan Y, Ryu CM. Enhancement of plant drought tolerance by microbes. In: Aroca R, editor. Plant responses to drought stress. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. pp. 383–413. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar BK, Ismail S, Patil VD. Role of microbial solubilisers on major nutrient uptake—a review. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(5):641–644. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Baweja M, Singh PK, Shukla P. Recent developments in systems biology and metabolic engineering of plant–microbe interactions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1421. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano T, Berberich T, Tateda C, Takahashi Y. Polyamines: essential factors for growth and survival. Planta. 2008;228(3):367–381. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey JR, Krishnan R, Botvinick EL (2017) Methods of manipulating alginate microcapsule size and permeability. US Patent Application 15(204), 916

- Lalitha S. Plant growth-promoting microbes: a boon for sustainable agriculture. In: Dhanarajan A, editor. Sustainable agriculture towards food security. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Muuller M, Chang MW, Frettlooh M, Schoonherr H. Encapsulation of autoinducer sensing reporter bacteria in reinforced alginate-based microbeads. ACS App Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(27):22321–22331. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez BR, Bashan Y, Trejo A, de Bashan LE. Amendment of degraded desert soil with wastewater debris containing immobilized Chlorella sorokiniana and Azospirillum brasilense significantly modifies soil bacterial community structure, diversity, and richness. Biol fertil soil. 2013;49(8):1053–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00374-013-0799-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. Seed coating with beneficial microorganisms for precision agriculture. Biotechnol Adv. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty T, Bhattacharjee S, Goswami M, Bhattacharyya P, Das B, Ghosh A, Tribedi P. Biofertilizers: a potential approach for sustainable agriculture development. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(4):3315–3335. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet F, Poinsot V, André O, et al. Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature. 2011;469(7328):58. doi: 10.1038/nature09622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malusa E, Sas-Paszt L, Ciesielska J. Technologies for beneficial microorganisms inocula used as biofertilizers. Sci World J. 2012 doi: 10.1100/2012/491206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena VS, Meena SK, Verma JP. Plant beneficial rhizospheric microorganism (PBRM) strategies to improve nutrients use efficiency: a review. Ecol eng. 2017;107:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.06.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutturi S, Sahai V, Bisaria VS. Fed-batch cultivation for high density culture of Pseudomonas spp. for bioinoculant preparation. In: Varma A, Sharma AK, editors. Modern tools and techniques to understand microbes. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak D, Lone R, Koul KK. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (amf) and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (pgpr) association in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.): a brief review. In: Kumar V, Kumar M, Sharma S, Prasad R, editors. Probiotics and plant health. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia A, Romero D, De Vicente A. Plant protection and growth stimulation by microorganisms: biotechnological applications of Bacilli in agriculture. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22(2):187–193. doi: 10.1021/bp025532t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri A, Padda KP, Chanway CP. Beneficial effects of bacterial endophytes on forest tree species. In: Maheshwari D, Annapurna K, editors. Endophytes: crop productivity and protection. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Egidi E, Liu H. New frontiers in agriculture productivity: optimised microbial inoculants and in situ microbiome engineering. Biotechnol Adv. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani U, Kumar V. Microbial bioformulations: present and future aspects. In: Prasad R, Kumar V, Kumar M, Choudhary D, editors. Nanobiotechnology in bioformulations. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy CA, Saravanan RS. Polymicrobial multi-functional approach for enhancement of crop productivity. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2013;82:53–113. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407679-2.00003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha PD, Lai WA, Arun AB, Young CC. Effect of free and encapsulated Pseudomonas putida CC-FR2-4 and Bacillus subtilis CC-pg104 on plant growth under gnotobiotic conditions. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98(2):447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaratnam S, Traquair JA. Formulation of a Streptomyces biocontrol agent for the suppression of Rhizoctonia damping-off in tomato transplants. Biol Control. 2002;23(3):245–253. doi: 10.1006/bcon.2001.1014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu PK, Gupta A, Singh M. Bioformulation and fluid bed drying. A new approach towards an improved biofertilizer formulation. In: Sengar RS, Singh A, editors. Eco-friendly agro-biological techniques for enhancing crop productivity. Singapore: Springer; 2018. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schoebitz M, Belchi MDL. Encapsulation techniques for plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. In: Arora NK, Mehnaz S, Balestrini R, editors. Bioformulations for sustainable agriculture. India: Springer; 2016. pp. 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Singh JS, Pandey VC, Singh DP. Efficient soil microorganisms: a new dimension for sustainable agriculture and environmental development. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2011;140(3–4):339–353. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2011.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P (2018) Development and characterization of cellulose based systems for the entrapment and delivery of probiotic bacteria (Doctoral dissertation, 00500: Universidade de Coimbra)

- Surendra KA, Baby A. Enhanced shelf life of Azospirillum and PSB (Phosphate solubilizing Bacteria) through addition of chemical additives in liquid formulations. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 2016;5(4):2023–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Suyal DC, Soni R, Sai S, Goel R. Microbial inoculants as biofertilizer. In: Singh DP, Singh HB, Prabha R, editors. Microbial inoculants in sustainable agricultural productivity. New Delhi: Springer; 2016. pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir HAS, Gu Q, Wu H, Niu Y, Huo R, Gao X. Bacillus volatiles adversely affect the physiology and ultra-structure of Ralstonia solanacearum and induce systemic resistance in tobacco against bacterial wilt. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40481. doi: 10.1038/srep40481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Kang H, Qin Z, Zhang K, Zhong Y, Li H, Mo L. Significance of manganese resistant Bacillus cereus strain WSE01 as a bioinoculant for promotion of plant growth and manganese accumulation in Myriophyllum verticillatum. Sci Total Environ. 2020;707:135867. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari S, Arora NK. Exopolysaccharides based bioformulation from Pseudomonas aeruginosa combating saline stress. Recent Trends PGPR Res Sustain Crop Product. 2016;2016:93. [Google Scholar]

- Timmusk S, Behers L, Muthoni J, Muraya A, Aronsson AC. Perspectives and challenges of microbial application for crop improvement. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:49. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmusk S, El-Daim IAA, Copolovici L, et al. Drought-tolerance of wheat improved by rhizosphere bacteria from harsh environments: enhanced biomass production and reduced emissions of stress volatiles. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo A, De-Bashan LE, Hartmann A, et al. Recycling waste debris of immobilized microalgae and plant growth-promoting bacteria from wastewater treatment as a resource to improve fertility of eroded desert soil. Environ Exper Bot. 2012;75:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P, Pandey A. Recovery of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria from sodium alginate beads after 3 years following storage at 4 C. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;35(3):205–209. doi: 10.1007/s10295-007-0284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P, Pandey A, Palni LMS. Carrier-based preparations of plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculants suitable for use in cooler regions. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;21(6–7):941–945. doi: 10.1007/s11274-004-6820-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ren W, Li Y, et al. Nontargeted metabolomic analysis to unravel the impact of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate stress on root exudates of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) Sci Total Environ. 2019;646:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warra AA, Prasad MNV (2020) African perspective of chemical usage in agriculture and horticulture—their impact on human health and environment. In: Majeti N, Vara P (eds) Agrochemicals detection, treatment and remediation butterworth-heinemann, pp 401–436. 10.1016/B978-0-08-103017-2.00016-7

- Wu Z, He Y, Chen L, et al. Characterization of Raoultella planticola Rs-2 microcapsule prepared with a blend of alginate and starch and its release behavior. Carbohyd Polym. 2014;110:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabur R, Bashan Y, Hernández-Carmona G. Alginate from the macroalgae Sargassum sinicola as a novel source for microbial immobilization material in wastewater treatment and plant growth promotion. J Appl Phycol. 2007;19(1):43–53. doi: 10.1007/s10811-006-9109-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young CC, Rekha PD, Lai WA, Arun AB. Encapsulation of plant growth-promoting bacteria in alginate beads enriched with humic acid. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95(1):76–83. doi: 10.1002/bit.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zago SL, dos Santos MF, Konrad D, Fiorini A, Rosado FR, Missio RF, Vendruscolo ECG. Shelf life of Azospirillum brasilense in alginate beads enriched with trehalose and humic acid. J Agric Sci. 2019;11:6. doi: 10.5539/jas.v11n6p269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A, Khan MS, Saif S, et al. Role of nitrogen-fixing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in sustainable production of vegetables. Current perspective. In: Zaidi A, Khan MS, et al., editors. Microbial strategies for vegetable production. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Moyne AL, Reddy MS, Kloepper JW. The role of salicylic acid in induced systemic resistance elicited by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria against blue mold of tobacco. Biol Control. 2002;25(3):288–296. doi: 10.1016/S1049-9644(02)00108-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar-Perez C, Ritte E, Chernin L. Preservation of chitinolytic Pantoaeag glomerans in a viable form by cellular dried alginate-based carriers. Biotechnol Progress. 2002;18(6):1133–1140. doi: 10.1021/bp025532t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]