Abstract

Worldwide hypertension (HT) guidelines recommend use of home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) in patients with persistent suboptimal blood pressure (BP) readings. It is not clear how patients with limited health literacy could perform HBPM to assist BP control. This study aimed at finding the association between HBPM and patients from lower socioeconomic classes, particularly on the effect of health literacy or educational level. Three electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PubMed) were searched for primary studies with keywords including educational level, health literacy, numeracy, home blood pressure monitoring, accuracy, and quality. The PRISMA guideline was followed. The quality of the literature was assessed by the Cochrane tool and modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Nineteen interventional studies and 29 cross-sectional studies were included. Different populations used different cutoffs to report patients' educational level, whereas health literacy was rarely measured. Three studies used psychometric validated tools to assess health literacy. The quality of HBPM could be assessed by the completion of the procedures' checklist or the number of HBPM readings recorded. The association between subjects' health literacy or educational level and the quality of HBPM was variable. The interventional studies showed that increasing professional-patient contact time could improve patients' knowledge, efficacy, and quality of HBPM. Conclusion. Patients' educational level and literacy were not the limiting factors to acquire high-quality HBPM. High-quality HBPM could be achieved by the structured educational intervention. The quality and amount of evidence on this topic are limited. Therefore, further studies are warranted.

1. Background

Among hypertensive patients, 10% to 50% of their office blood pressure (BP) readings are higher than the home blood pressure readings [1]. In patients presented with uncontrolled hypertension in our daily practice, home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) (also known as self-blood pressure monitoring (SBPM)) is an essential monitoring option especially for patients with a suspected white coat effect or masked hypertension. It has become an important recommendation in most international hypertension management guidelines [2–4]. HBPM was also shown to improve office BP readings, increase BP control rate, and enhance the quality of life at low patient risk [5]. The beneficial effect could be reassured when HBPM is delivered with other forms of interventions, such as patient education or drug titration [5, 6]. Therefore, health care professionals routinely recommend HBPM to patients with high office BP.

Compared with standard ambulatory BP measurement, HBPM had mean sensitivity of 85.7% (78.0% to 91.0%) and specificity of 62.4% (48.0% to 75.0%) in diagnosing hypertension [7]. The relatively large range of sensitivity and specificity highlighted various factors affecting the accuracy of HBPM. The HBPM readings may be inaccurate due to patients' inappropriate operation, withholding undesirable readings, or inaccurate automated devices. Parker et al. indicated that there was an end-digit preference for zero numbers and specific-value preference for readings just below the alert threshold among patients in self-reporting their BP [8]. In addition, as there were large varieties of home blood pressure monitors available in the market, their accuracy could be questionable. An assessment done by Ringrose et al. revealed that most home BP devices were not accurate to within 5 mmHg [9].

As a result, health care professionals could prescribe inappropriate management according to inaccurate HBPM records.

From a patient's perspective, performing HBPM is not always an easy task. Patients with lower self-efficacy, lower educational levels, or lower health literacy may need special interventions to assist home monitoring. Fletcher et al. illustrated patients' and health care professionals' concerns of HBPM in a qualitative review, as HBPM involved interpretation, attribution, and action [10]. The quality of HBPM could be highly operator-dependent. Any inaccurate readings or wrong interpretation may lead to patient anxiety, overdiagnosis, or overtreatment due to falsely high home BP readings. On the other hand, falsely low home BP may lead to false reassurance, underdiagnosis, or poor drug compliance.

Different elements are required to perform high-quality HBPM as described in clinical guidelines. They include access to accurate BP monitors, skills, and knowledge to perform HBPM, motivation to perform HBPM regularly, and accurate reflection of HBPM readings to their health care providers. Patients may not have the hardware, skill, and knowledge to implement successful HBPM. They need health care providers' instruction and feedback to practice HBPM independently. Their skills and BP records should be reviewed regularly in order to ensure their compliance with HBPM protocol, such as measurement preparation, procedure, and how to record BP readings. In a busy primary care practice, time constraints may preclude physicians from taking time to educate HBPM and review patients' home BP records.

Conventionally, many studies assessed patients' educational level as part of the sociodemographic background instead of assessing patients' health literacy specifically. “Health Literacy” (HL) is the patient's ability to read, interpret, and respond to the information during health care activities. It was defined by the American Medical Association in 1999 as “the constellation of skills, including the ability to perform basic reading and numeral tasks required to function in the healthcare environment” [11]. Underprivileged patients, such as those from lower socioeconomic class, those with lower educational levels, or those with limited health literacy or numeracy, were found to have a poorer outcome in overall noncommunicable diseases [12]. In addition, patients with inadequate health literacy were more likely to have poorer disease knowledge, poorer self-efficacy, and misconception in cardiovascular disease [13]. They may also encounter greater barriers in performing accurate HBPM. Few studies have focused on whether the underprivileged patients were able to perform HBPM as good as middle or above socioeconomic class patients.

Given the large and increasing global disparities of BP control in hypertensive patients from the low-income population, there is a clinical urge to formulate suitable interventions which could help patients achieve desirable BP targets [14]. Most of the existing review papers focused on the BP outcomes of the global hypertensive population after different HBPM interventions [5–7, 10]. So far, there is a limited understanding of how the socially disadvantaged population could successfully perform high-quality HBPM that could subsequently improve their BP control. This study aimed to find out the association between patient health literacy (including educational level and other related socioeconomic factors) and HBPM, which may or may not lead to improvement of BP control. The finding will be particularly useful to the low-income hypertensive populations.

2. Methods

We performed a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline to investigate the association between HBPM and patients' health literacy or educational level [15].

2.1. Selection of Studies

We included all original research articles evaluating adult practice or attitude towards HBPM or SBPM, which include knowledge, skills, and practice towards HBPM or SBPM. The articles should contain an association of subjects' ability to read, understand, and follow instructions, such as educational level, health literacy, and numeracy with either HBPM or overall BP control. The articles could include processes of HBPM or SBPM, practices such as the prevalence of HBPM or SBPM, and skills or knowledge of HBPM or SBPM. There was a preferable analysis of the association between study subjects' ability and quality of HBPM or SBPM.

We excluded studies with neither analysis of HBPM or SBPM practice nor subjects' educational level or health literacy.

2.2. Search Strategy

We performed a web-based search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PubMed databases. We also screened the reference list of all relevant studies (snowball search). Studies published in English from 1910 to present were included.

We defined two main search concepts (“self-blood pressure monitoring” and “appropriateness of self-care activities”) and combined the search by “AND.” We used the MeSH term “blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory” or the term “self-blood pressure monitoring” or “self-blood pressure measurement,” “home blood pressure monitoring,” “self-measurement,” and “blood pressure.” We then used the term “health literacy,” “mathematics,” “numeracy,” “educational level,” “educational status” or “health knowledge, attitude, practice.” We limited searching by studies for adults (age > 18) The whole syntax is shown in Table 1. The date of the last search was on 27 November 2019.

Table 1.

Searching strategies.

| PubMed | MEDLINE | EMBASE |

|---|---|---|

| (1) (“Health literacy” [MeSH] OR (2) “Patient education” as Topic [MeSH] OR (3) “Health status disparities” [MeSH] OR (4) “Educational status” [MeSH] OR (5) “Health education” [MeSH]) AND (6) Blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory [MeSH major topic] (7) Limited to English language |

(1) Home monitoring/or home care/ (2) Reading/or health education/or health literacy/ (3) Patient compliance/ (4) Education program/or interdisciplinary education/or education/or health education/or patient education (5) Blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory (6) Self-care/ (7) Educational status/ (8) Patient education as topic/ (9) “Reproducibility of results”/ (10) Essential hypertension/or White coat hypertension/or masked hypertension/or MEDLINE / (11) 1 or 5 or 6 (12) 2 or 4 or 7 or 8 (13) 3 or 9 (14) 10 and 11 and 12 and 13 (15) Limit 14 to (English language and (MEDLINE or “PubMed not MEDLINE”)) |

(1) Blood pressure monitoring/ (2) Home monitoring/or home care/ (3) Self-monitoring/ (4) Reading/or health education/or health literacy/5. Health disparity/6. Patient compliance/ (7) Reproducibility/ (8) Essential hypertension/ (9) White coat hypertension/ (10) 1 or 2 or 3 (11) 8 or 9 (12) Education program/or interdisciplinary education/or health education/or patient education/ (13) 4 or 5 or 12 (14) 10 and 11 and 13 (15) Limit 14 to (English language and (EMBASE or MEDLINE)) |

| 70 items found | 63 items found | 62 items found |

2.3. Selection of Publications

We went through a two-step selection process. We first read the titles and abstracts. Studies meeting all inclusion criteria above were identified as potentially appropriate. We then analyzed the full texts of the selected articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion were documented.

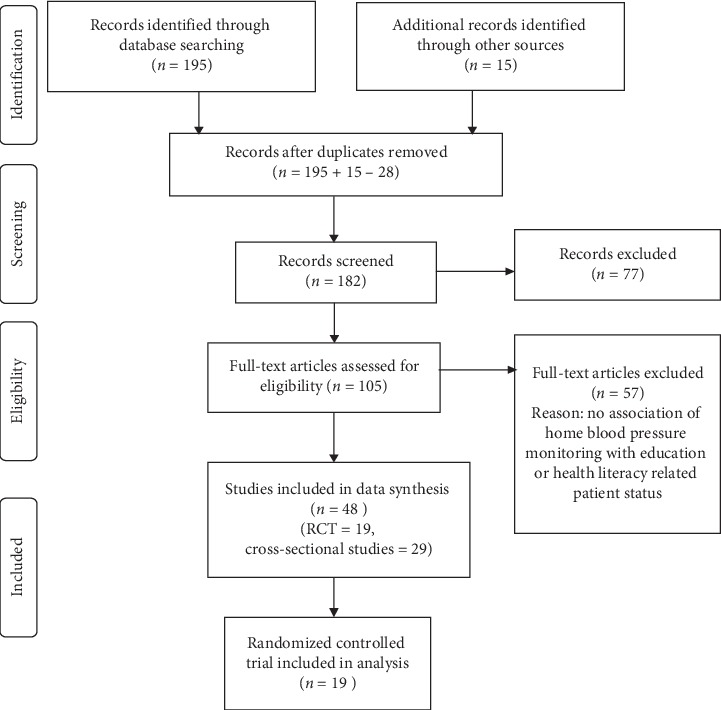

Two independent review authors (SF and MD) did the whole selection process. Disagreements between us were resolved by consensus. A review author (either CW or BC) was consulted if disagreement persisted. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 1 [16].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The selection of the studies is based on the following criteria:

The article is an original study, which includes a detailed study method for the assessment of the risk of bias.

The quantitative studies included assess the association between health literacy or numeracy or educational status of patients and their practice or knowledge on SBPM or HBPM or evaluate the interventions to enhance HBPM practice by enhancing the efficacy of HT patients.

The patient outcomes of studies involved HBPM attitude, knowledge, and practice; or the outcome involved hypertension BP control.

The studies centered on adult patients with an established diagnosis of hypertension. The studies that focused on diagnostic tests, screening of hypertension, and hypertension in pregnancy were excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction

We extracted bibliographic data (author, publication year, title, and journal), study design, setting, country, inclusion and exclusion criteria, subject recruitment, study population characteristic (age and gender), and date and duration of the study. We registered the tools used for assessing the outcome measurement and if there is an association between the subjects' health literacy and the appropriateness of HBPM. We retrieved all outcome categories. Finally, we extracted the HBPM-related interventions and patient outcome particularly for subjects with relatively low health literacy or educational level.

2.5. Quality Assessment

Critical appraisal was independently recorded by reviewers to allow comparison. Risk of bias was assessed by considering relevant domains to interventional studies, including participant selection, measurements of variables, and controlling for confounding, in line with the Cochrane Collaboration's Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tool for assessing the risk of bias [17, 18]. Each domain was rated with “high,” “low,” or “unclear” according to the risk of bias, with free text explanations. In order to maximize relevance to nonrandomized studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional studies was used [19]. Two authors (SF and MD) assessed the individual study by three domains which are selection (maximum 5 stars), comparability (maximum 2 stars), and outcome (maximum 3 stars) resulting in total NOS grade. The summation of the 3 domains' number of stars resulted in the total NOS score. Very good studies scored 9-10 stars, good studies scored 7-8 stars, satisfactory studies scored 5-6 stars, and unsatisfactory studies scored 0–4 stars.

2.6. Data Synthesis

We separately collected the cross-sectional studies and the interventional studies data for narrative synthesis. Different assessments of educational level and/or health literacy, HBPM device, technique, and quality of HBPM were recorded.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the systematic search and selection of relevant studies adopting the PRISMA guideline 2009 [16]. 195 studies were identified from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PubMed. Bibliographies of primary studies and review articles meeting the inclusion criteria were searched manually to identify 15 further eligible studies. 182 unique studies in total were included for the screening of abstracts. After reviewing the abstracts, 77 studies were excluded because the studies did not assess HBPM or self-BP monitoring, or the research subjects were not hypertensive patients, nor was there any association between HBPM and patients' educational status or health literacy. 105 studies were included for full-text assessment of eligibility. Finally, 48 studies (19 randomized controlled trials and 29 cross-sectional studies) were included in the data synthesis.

The results of cross-sectional studies are shown in Table 2. The included studies were performed in North America, Europe, and Asia from 2003 to 2019. Most of the participants were patients with hypertension. Two of the studies surveyed pharmacists and primary care providers such as nurses and physicians about their clinical practice of HBPM. Study sites included a populational survey, recruited in community organizations, primary care clinics, or outpatient clinics in the hospital. Most studies demonstrated a positive relationship between subjects' educational level or health literacy is associated with owning BP monitors at home, performing it regularly or recording the measurements accurately. Five out of twenty-nine studies reported a negative association between patient educational level or other social factors and practice of HBPM. The BP outcomes of patients were included in 5 studies: 2 studies showed a positive association of HBPM and BP control, while 3 studies did not demonstrate any better BP control.

Table 2.

Summary of the selected cross-sectional studies.

| Lead author [Ref], country, year | N | Level of education, health literacy, or other social factors | Any association between educational level and HBPM? | Any association between educational level and better BP control? | NOS grading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allibe et al. [20], France, 2016 | 380 | Education level <A-level, A-level, >A-level hypertension knowledge |

NA | Yes, knowing the correct BP target is significantly associated with normal BP | S∗C O∗ 2/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Ayala et al. [13], USA, 2017 | 559 | ≤High school graduate, some college graduate, or more | Yes, older age, and those who believe lower BP can reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke had higher % of HBPM Educational level is not associated with HBPM use | NA | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 6/10 = Satisfactory |

| Ayala et al. [21], USA, 2008 | 3739 | <High school graduate high School graduate Some college College graduate or more |

neutral, regular HBPM users had an insignificantly higher educational level Subjects who perceived HBPM helped control their BP Measured BP more frequently |

NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Bancej et al. [22], Canada, 2010 | 6142 | Educational attainment Less than secondary school Secondary school graduate Some after secondary Postsecondary graduate |

Yes, regular HBPM was more likely among older adults; those who believed to control BP; and those who had been shown how to perform HBPM by a health professional No, HBPM practice was not related to the level of education |

NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Breaux-Shropshire et al. [23], USA, 2012 | 149 | NA | NA | No, HBPM was not a predictor of blood pressure control | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗ 6/10 Satisfactory |

| Cacciolati et al. [24], France, 2012 | 1,814 | High: ≥12 years formal education Low: <12 years of formal education Cognitive level: MMSE autonomy: Lawton scale Five basic daily activities |

Yes, less HBPM in subjects age >80, with lower educational level and those had no autonomy | NA | S∗∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 8/10 = Good |

| Cai et al. [25], China, 2017 | 1878 | Illiterate/primary or above | Yes, those with higher education were more likely to perform HBPM | NA | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Cuspidi et al. [26], Italy, 2005 | 855 | Primary/secondary/tertiary year of education | Yes, those with higher educational level used HBPM more frequently | NA | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Dymek et al. [27], Poland, 2015 | 14 | 10 items patients' knowledge score Primary, secondary, university, or above | Yes, overall subjects had fair compliance to HBPM Results showed deficiency in both knowledge and skills |

NA | S∗C O∗∗ 3/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Flacco et al. [28], Italy, 2015 | 725 | None/elementary Middle/high school Bachelor/higher |

No, high-quality HBPM is not related to the educational level Yes, better quality if subjects received HBPM instructions from doctors or pharmacists |

NA | S∗C∗∗O∗∗ 5/10 Satisfactory |

| Gohar et al. [29], UK, 2008 | 153 | Mean years in education = 12.25 years | No, it was not associated with gender, alternative or complementary medicine use, or adherence to medication | NA | S∗CO∗ 2/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Hu et al. [30], China, 2013 | 318 | Years of education ≤6 years; >6 years |

Yes, older participants (>or = 65) were more likely to perform HBPM No, educational level is not related to the practice of HBPM |

NA | S∗∗C O∗∗ 4/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Kim et al. [31], USA, 2010 | 377 | Scoring of high BP knowledge Cut-off at <90th percentile or ≥90th percentile |

No, compliance with HBPM is not associated with HT knowledge or educational level | NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 8/10 = Good |

| Melnikov [32], Israel, 2019 | 430 | Years of education Total hypertension knowledge score |

Yes, more years of education and those who performed HBPM had better knowledge of hypertension | NA | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 6/10 = Satisfactory |

| Merrick et al. [33], USA, 1997 | 91 | Years of education Cutoff <12 years & ≥12 years |

No, the accuracy of BP measurement is not related to the factors assessed | NA | S∗C O∗∗ 3/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Milot et al. [34], Canada, 2015 | 1010 (2010) 1005 (2014) |

Received HBPM recommendations from their doctors | Only 15% of patients in 2010 and 18% in 2014 were defined as sufficiently compliant with all HBPM procedures | NA | S∗∗C∗O∗ 4/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Mitchell et al. [35], USA, 2015 | 193 | College graduate/some college/< high school | No, HBPM is not associated with BP levels, age, sex, race, or education level | NA | S∗∗C O∗ 3/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Naik et al. [36], USA, 2008 | 212 | Older adults, some college education Self-management behaviors Communication factors |

Yes, patients' endorsement of a shared decision-making style is associated with more HBPM | Yes, proactive communication with one's clinician about abnormal HBPM is associated with better BP control | S∗∗∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 9/10 = very good |

| Ragot et al. [37], France, 2005 | 104 pharmacists 1015 patients |

Patients' knowledge for lifestyle change for HT, equipped with an automatic HBPM device, knew the name of drugs, treatment-related side effects, and drug compliance | Yes, 90% reported using the device without any rule. In all, 10% of the patients followed doctor's or pharmacist's recommendations | No, those had higher educational level had better hypertension knowledge, but were not better BP controlled | S∗C∗∗O∗ 4/10 = unsatisfactory |

| Rao et al. [38], USA, 2015 | 409 | Some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine-short form (REALM-SF) numeracy: 3-item numeracy measure |

Yes, adequate numeracy, but not high literacy is associated with more complete reporting of HBPM | NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 8/10 = Good |

| Seidlerová et al. [39], Czech, 2014 | 449 | Primary, secondary, university | Yes, older age, university education, married, and longer duration of HT were more likely to have HBPM device Regular HBPM is associated with the no. of HT drugs |

No, BP control is not associated with frequency of HBPM | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 6/10 = Satisfactory |

| Shi et al. [40], China, 2017 | 523 | Primary, middle, high school, higher education Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Hypertension |

Yes, higher HL was more compliant with HBPM | NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗ = 6/10 Satisfactory |

| Tan et al. [41], Singapore, 2005 | 224 | None and primary Secondary Tertiary/poly/graduate |

Yes, HBPM use was associated with higher-income status Nonusers were associated with failure to recognize benefits, HBPM awareness, understanding of device operation, and perception of HBPM inaccuracy |

NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Tirabassi et al. [42], USA, 2013 | 1254 | Different primary care providers (PCPs) | Yes, PCPs were less likely to recommend HBPM to their patients if they were from poor to the lower middle class than those PCPs with most patients from higher economic classes | NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 7/10 = Good |

| Tekin et al. [43], Turkey, 2012 | 2747 | Illiterate Literate/primary school Graduate Middle school graduate High school graduate University graduate |

Yes, higher educational level and higher-income level are associated with possession of HBPM | NA | S∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 8/10 = Good |

| Tyson and Mcelduff [44], UK, 2003 | 222 | College or university | Yes, subjects who had further education were more likely to own HBPM and participate in monitoring | NA | S∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 6/10 = Satisfactory |

| Uzun et al. [45], Turkey, 2009 | 150 | Illiterate Literate but no graduation Graduated from elementary school Junior high school High school License program |

Yes, informed about HT & CVD risk factors informed is better and education level (higher is better) | NA | S∗C∗∗O∗∗∗ 6/10 Satisfactory |

| Viera et al. [46], USA, 2008 | 530 | <High school graduate High school graduate Some college or more |

Yes, 35.2% of patients report that their physicians had recommended HBPM to them | NA | S∗∗∗∗∗C∗∗O∗∗ 9/10 = very good |

| Wang et al. [47], China, 2014 | 1915 | Junior high school Senior high school College |

Yes, subjects with college education used HBPM more frequently than those with middle school education | NA | S∗C∗∗O∗∗ 5/10 Satisfactory |

CSS = cross-sectional study, CVD = cardiovascular disease, Ref = reference number, N = number of hypertensive subject, NA = not available, HBPM = home blood pressure monitoring, HT = hypertension, BP = blood pressure, HL = health literacy, NOS = Newcastle-Ottawa score for cross-sectional studies, S = selection, C = comparability, O = outcome, OR = odds ratio.

The quality assessment by Newcastle-Ottawa Score for cross-sectional studies found the studies ranged from very good (grade 9/10) to unsatisfactory (grade 2/10). Most unsatisfactory studies got low sampling scores.

Table 3 shows the results of the 19 interventional studies. Most studies were performed in North America, while 2 of them were performed in Europe and one of them was performed in Hong Kong. There were different modes of HBPM interventions, such as providing home BP monitors, patient education, and training intervention, record and feedback system to HBPM measurements, training, and updating knowledge to health care providers.

Table 3.

Summary of a selected randomized controlled trial.

| Author | N | Level of education/Health literacy/Social factors | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Any association between educational level and home BP monitoring? | Do the interventions result in better BP control? | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachmann et al. [48], Switzerland, 2002 | 48 | NA | Subjects received information about the storage capabilities of HBPM | Subjects did not receive information about the storage capabilities of HBPM | Manipulation of HBPM values for the first time. Accuracy and interpretation of HBPM may be increased by using devices with a memory | Y | NA | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Binstock and Franklin [49], USA, 1988 | 120 | NA | HBPM or a combination of techniques | Education alone, contract, or pill packs alone | SBP and DBP | NA | Y | ⊕ low |

| Brenna et al. [50]. USA, 2010 | 485 | 94% ≥graduated high school | Telephonic nurse DM: educational materials, lifestyle, and diet counselling HBPM versus HBPM alone |

Light support educational program | Increase proportion with BP < 120/80 mmHg, mean systolic BP, mean diastolic BP, and frequency of HBPM after the intervention | Y | Y | ⊕⊕ low to moderate |

| DeJesus et al. [51], USA, 2009 | 54 | NA | (1) Nurse educator conducted class + HBPM (2) Nurse educator class |

Usual care | Only 20% achieved the target BP of 130/80 mmHg and there was no statistical difference in mean systolic and diastolic BP among the three groups | NA | N | ⊕ low |

| Figar et al. [52], Argentina, 2006 | 60 | Year of education | Compliance-based model includes HBPM | Patient empowerment model of education | Change in systolic BP by 24 h ABPM | NA | N | ⊕⊕ low to moderate |

| Fung et al. [53], Hong Kong, 2003 | 240 | NA | Individual education by research assistance of HBPM device operation Self-practice under supervision Checkpoints are correct |

Usual care | No significant difference in BP changes between the two groups |

Y | N | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ moderate to high |

| Green et al. [54], USA, 2008 | 778 | <12 years Some after high school 4-year college After 4-year college |

HBPM and secure patient web services training + pharmacist care management delivered through web communications | Usual care | BP level | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Haynes et al. [55], Canada, 1976 | 38 | Steelworkers | Taught how to measure their own BP, chart their pill-taking, taught how to tailor pill-taking to their daily habits and rituals, FU by nonprofessionals | Usual care | Improvement in drugs compliance and BP | NA | Y | ⊕⊕ low to moderate |

| Kauric-Klein and Artinian [56], USA, 2007 | 34 | Year of education | HBPM | Usual care | Improvement in SBP but not DBP | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ moderate to high |

| Kim et al. [57], USA, 2014 | 369 | HT knowledge self-efficacy: HT belief scale; HT health literacy scale ≤ middle school graduate; high school graduate; ≥some college | 2-hour weekly educational sessions × 6 on HBP management skill building, including health literacy training, followed by telephone counselling and HBPM for 12 months | Intervention delay | Intervention group showed improvement in mean SBP & DBP Improvement in health literacy in 12 and 18 months adherence to HT medication, self-efficacy, and HBP knowledge and less depression |

NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Maciejewski et al. [58], USA, 2014 | 591 | Completed <12 years of education | 3 telephone-based interventions: nurse administered health behavior promotion Provider-administered medication adjustments based on HT treatment guideline Combination of both |

Usual care | Patients randomized to the combined arm had greater improvement in the proportion of BP control during and after the 18-month trial | Y | Y | Unclear |

| Magid et al. [59], USA, 2011 | 338 | High school education | Patient education including remote HBPM, reporting to an interactive voice response IVR phone system Pharmacists follow-up |

Usual care | No difference in proportion of achieving BP goal at 6 months Reduction of mean SBP and DBP |

NA | N | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Morgado et al. [60], Portugal, 2011 | 197 | Illiterate, elementary schooling, high schooling, university education | Quarter FU by a hospital pharmacist Provided patient education goal BP to achieve, medication education and recommendations to the physician regarding changes in drug therapy |

No pharmacist care | Better medication adherence, significant lower SBP and DBP were observed in the intervention group | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

| Nessman et al. [61], USA, 1980 | 52 | Noncompliance patient | HBPM education patients select BP drugs emphasizing self-help informed program | Listened to audiotape on hypertension knowledge and management nurse adjusted the drug regimens | Lower DBP better pill counts better attendance |

NA | Y | Unclear |

| Ogedegbe et al. [62], USA, 2014 | 1059 | ≤High school Some college Some graduate school |

4 modules of interactive computerized patient education HBPM Monthly lifestyle counselling clinicians CME based training, HT case round, clinical audits of patient office BP readings |

Patients and physicians received printed patient education material and hypertension treatment | Marginal significantly greater BP control in patients with moderate to good health literacy | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Victor et al. [63], USA, 2011 | 1022 | Black-owned barbershops </=high school college postgraduate |

10 weeks of baseline BP screening offer BP checks with haircuts promote physician check-up Sex-specific peer-based health messaging |

Received standard BP pamphlets | Improvement in hypertension control rate | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Yi et al. [64], USA, 2015 | 900 | Hispanic urban population Uninsured |

Received a home blood pressure monitor and training on use | Usual care | No significant difference in BP changes | NA | N | ⊕⊕ low to moderate |

| Yoo et al. [65], Korea, 2009 | 123 | NA | Ubiquitous chronic disease care system using the cellular phone Internet for overweight patients |

Usual care | Significant reduction of BP in the intervention group | NA | Y | ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Zillich et al. [66], USA, 2005 | 125 | Pharmacists provided patient-specific education | Control group care + patient and physician educational program about hypertension treatment and monitoring | Provided with an HBPM device, instructed to measure BP > once daily for 1 month | More reduction of BP in the intervention group | NA | Y | ⊕⊕ low to moderate |

BP = blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; FU = follow up; HBPM = home blood pressure monitoring; N = No; NA = not available/applicable; SBP = systolic blood pressure; Y = Yes.

3.1. HBPM in the Included Studies

There were various types of home BP monitors involved in selected studies. They included automatic electronic branchial devices, electronic semi-automated branchial devices, manual mercurial sphygmomanometer, and electronic wrist devices. The possession of home BP monitors was related to higher educational level and/or income status [20, 25, 41, 44], while the frequency of HBPM as clinician recommended was not necessarily related to the educational level. Ragot et al. found that 90% of HBPM users did not receive information about HBPM use [37]. Other studies demonstrated that the HBPM quality might not be related to the educational level. When patients were instructed to use HBPM by health care providers, there was consistent reporting of regular HBPM use [22, 28, 36, 46].

There was no psychometrically validated tool to assess the quality of HBPM. The quality of HBPM was assessed by different tools defined by authors in different studies. Some used the number of successfully documented or transmitted BP readings over the number of expected BP readings as high-quality HBPM. Flacco et al., Dymek et al., and Fung et al. used procedure checklists developed according to HBPM guidelines to get the total quality scores [27, 28, 53]. Either a video recording of the HBPM procedure or a direct-observation method could be used to assess the HBPM procedure. Dymek et al. demonstrated a deficiency in both knowledge and skills in HBPM in 14 hypertensive patients, while Flacco et al. showed adequate HBPM quality in more than 80% of the subjects. Merrick et al. assessed HBPM quality by comparing the BP readings by a trained volunteer with that by research subjects [33].

3.2. Educational Status

Most studies assessed the subjects' educational status. The educational level was usually self-reported as part of personal characteristics. The assessment method could be highly heterogeneous. Most studies categorized educational attainment into different levels of schools: primary schools, middle schools, high schools, and colleges, but the cutoff level and the number of categories highly varied. Three studies included “illiterate” as one of the educational status categories [25, 43, 45]. Other studies also included years of education for data synthesis. If the number of years was defined as binary categories, their cutoff years could vary from 5 years to 12 years.

3.3. Health Literacy

HL was not commonly assessed in studies of HBPM. Only 3 studies used 4 different validated health literacy (or numeracy) scales for assessment. Kim et al. used the High Blood Pressure Health Literacy Scale [57]. They did not categorize the subjects as high or low HL. They measured the change in HL before and after the intervention. Shi et al. used the Chinese Health Literacy Scale for Hypertension [40]. More than half of their study subjects (55.3%) had low health literacy. Rao et al. used the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form (REALM-SF) and the 3-item numeracy measure [38]. Less than one-third of the subjects (31%) had low numeracy. These three studies found a strong association between health literacy or numeracy with educational status.

3.4. Other Assessments of Patients' Ability

Apart from educational status and health literacy, six studies quantified the subjects' ability by different knowledge scores. The scoring items included knowledge about hypertension, hypertension complications, hypertension comorbidity, and HBPM [20, 27, 31, 32, 37, 57].

3.5. Association between HBPM and Educational Status or Health Literacy

In some studies, subjects with higher educational levels were not found to use more HBPM [21, 28, 29, 31, 35, 64]. However, in one study, a larger proportion of subjects with higher educational levels used HBPM [25]. Subjects who believed HBPM could help BP control performed more regular HBPM [21, 36, 41]. Some studies showed that patients with higher educational levels, higher HL, or higher numeracy could perform higher quality of HBPM, such as better compliance with HBPM procedure and more complete or accurate HBPM record [26, 38, 45, 47]. Flacco et al. did not find such an association. Instead, they found that patients performed higher quality of HBPM if they received HBPM instructions from pharmacists or doctors than if they received them from nonprofessionals [28].

3.6. Interventions to Improve HBPM for Patients with Different HLs

The interventional studies described different complex interventions that targeted patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Some of them targeted socially disadvantaged subjects, i.e., Korean American older patients and African Americans [57, 62]. Kim et al. used multiple patient educational sessions to focus on hypertension management skill building, HL training, followed by telephone counselling and HBPM. It is reflected that patients had improvement in HL, self-efficacy, and BP control after the intervention. In another study, Ogedegbe et al. used computerized interactive patient education modules, lifestyle counselling, HBPM, clinicians' continuous medical education training, clinicians' case round, and audit of patients' BP reading. They demonstrated that patients with moderate to good HL had marginal significant improvement in BP control [62]. Most interventions resulted in improvement in BP readings or BP control rate, while some reported no significant difference in BP outcomes. Few studies analyzed the elements that resulted in better BP control. Morgado et al. showed improvement in both patient drug adherence and BP control [60, 61].

4. Discussion

In this review, the educational status might or might not be associated with HBPM practice, quality, and compliance. The finding was particularly significant for patients with lower socioeconomic status. It was known that patients with lower educational status and lower income had a higher risk of hypertension and more nonadherence to antihypertensive treatment, subsequently leading to poorer clinical outcomes [67]. Health care providers could consider HBPM as an intervention which could improve drug adherence and BP control. Important elements included coaching patients on proper selection of HBPM devices and correct HBPM techniques (e.g., accurate recording of home BP readings). It could be done by providing home devices that store multiple BP readings, or uploading readings to smartphones or computers, or transmitting them directly to electronic health records.

Although various hypertension guidelines recommended the use of HBPM in diagnosis, the overall possession and compliance to HBPM were suboptimal.

We also identified that after structured training, socially disadvantaged patients could have significant improvement in HL, self-efficacy, and BP control. We suggested a structured intervention for identifying patients with low HL and offering training of hypertension self-care including HBPM, with the effect of improving BP control and increasing patients' HL. In view of the fact that less than 40% of the hypertensive patients had optimal BP control in different populations, the promotion of high-quality HBPM in patients with uncontrolled hypertension should be a clinical priority.

There was no structural or validated tool for assessing the quality of HBPM. The quality of HBPM depends on a validated BP device, competence of patients to perform HBPM on their own with a correct method and frequency, a record of accurate HBPM reading, and sharing of that record with health care professionals. Studies in this review modified recommendations of HBPM procedures from various international guidelines. Some studies also adopted the teletransmission of BP readings via the electronic system. We, therefore, suggest future research to develop a patient-friendly protocol to assess high-quality HBPM.

We also found that only a small proportion of studies focused on the assessment of HL and the outcome of hypertension control. The most common assessment is the educational status, which may be unrelated to patients' performance or compliance with antihypertensive treatment. The EHS Guideline proposed that the first step to tackle patients with poorly controlled chronic illness should be patient-centered care: to identify patients' barriers to better control the disease [1]. For instance, health care professionals should be well-equipped with communication techniques with low HL patients. Rajah et al. summarized that healthcare professionals should use everyday language and teach-back method and provide patients with reading materials and aids. However, the most commonly reported barrier regarding patient-centered care is time constraints.

4.1. Strength of the Study

This is the first study focusing on HBPM and its association with patients' education level, including health literacy, numeracy, and other socially related factors. Most studies were performed in community or outpatient settings, where primary care observation or intervention could be applied.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

Heterogeneous assessment of HBPM or SBPM, the prevalence of HBPM, and the educational status of patients are limitations of this study. Validated assessment of health literacy is sparse.

5. Conclusion

Patients' educational or health literacy levels were not limiting factors to acquire skills and knowledge of HBPM. High-quality HBPM could be achieved by structured educational interventions. Complex interventions involving patient education, providing valid home BP monitors, and facilitating patient-clinician communication may improve BP control. Those interventions should be tailor-made to subjects with low educational levels, which could be equally effective in improving the overall BP control.

Abbreviations

- BP:

Blood pressure

- C:

Comparability

- CVD:

Cardiovascular disease

- DBP:

Diastolic blood pressure

- EHS:

European hypertension society

- FU:

Follow-up

- HBPM:

Home blood pressure monitoring

- HL:

Health literacy

- N:

No

- NA:

Not available/applicable

- NOS:

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- O:

Outcome

- OR:

Odds ratio

- RCT:

Randomized controlled trial

- S:

selection

- SBP:

Systolic blood pressure

- SBPM:

Self-blood pressure monitoring

- Y:

Yes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

SF, MD, CW, and BC participated in the study design and data synthesis. SF and MD performed the search, and SF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MD, CW, and BC commented on this draft and performed critical revisions. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Table 3: quality assessment of the selected interventional studies.

References

- 1.Gorostidi M., Vinyoles E., Banegas J. R., de La Sierra A. Prevalence of white-coat and masked hypertension in national and international registries. Hypertension Research. 2015;38(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/hr.2014.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton P. K., Carey R. M., Aronow W. S., et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parati A. G., Stergiou M. G., O’Brien A. E., et al. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Journal of Hypertension. 2014;32(7):1359–1366. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack T., Krause T., O’Flynn N. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2012;62(596):163–164. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12x630232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omboni S., Gazzola T., Carabelli G., Parati G. Clinical usefulness and cost effectiveness of home blood pressure telemonitoring: meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Journal of Hypertension. 2013;31(3):455–468. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e32835ca8dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker K. L., Sheppard J. P., Stevens R., et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002389.e1002389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkinson J., Mant J., Martin U., et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342(7814):p. d3621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker R., Paterson M., Padfield P., et al. Are self-reported telemonitored blood pressure readings affected by end-digit preference: a prospective cohort study in Scotland. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019431.e019431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ringrose J. S., Polley G., McLean D., Thompson A., Morales F., Padwal R. An assessment of the accuracy of home blood pressure monitors when used in device owners. American Journal of Hypertension. 2017;30(7):683–689. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher B. R., Hinton L., Hartmann-Boyce J., Roberts N. W., Bobrovitz N., McManus R. J. Self-monitoring blood pressure in hypertension, patient and provider perspectives: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016;99(2):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs. AMA. Health literacy: report of the council on scientific affairs. JAMA. 1999;281(6):552–557. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisz G., Vignola-Gagné E. The world health organization and the globalization of chronic noncommunicable disease. Population and Development Review. 2015;41(3):507–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayala C., Tong X., Neeley E., Lane R., Robb K., Loustalot F. Home blood pressure monitoring among adults—American Heart Association cardiovascular health consumer survey, 2012. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2017;19(6):584–591. doi: 10.1111/jch.12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills T. K., Bundy D. J., Kelly N. T., et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–450. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panic N., Leoncini E., de Belvis G., Ricciardi W., Boccia S. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. European Journal of Public Health. 2013;23(suppl_1) doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt124.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt G., Oxman A. D., Akl E. A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt G. H., Oxman A. D., Vist G., et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias) Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allibe M., Babici D., Chantrel Y., et al. Appraisal of the knowledge of hypertensive patients regarding blood pressure control and comorbidities: results of a French regional survey. High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention. 2016;23(4):365–372. doi: 10.1007/s40292-016-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala C., Tong X., Keenan N. L. Regular use of a home blood pressure monitor by hypertensive adults—healthstyles, 2005 and 2008. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2012;14(3):172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bancej C. M., Campbell N., McKay D. W., Nichol M., Walker R. L., Kaczorowski J. Home blood pressure monitoring among Canadian adults with hypertension: results from the 2009 survey on living with chronic diseases in Canada. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2010;26(5):e152–e157. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70382-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breaux-Shropshire T. L., Brown K. C., Pryor E. R., Maples E. H. Relationship of blood pressure self-monitoring, medication adherence, self-efficacy, stage of change, and blood pressure control among municipal workers with hypertension. Workplace Health & Safety. 2012;60(7):303–311. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20120625-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cacciolati C., Tzourio C., Dufouil C., Alpérovitch A., Hanon O. Feasibility of home blood pressure measurement in elderly individuals: cross-sectional analysis of a population-based sample. American Journal of Hypertension. 2012;25(12):1279–1285. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai L., Dong J., Cui W. L., You D. Y., Golden A. R. Socioeconomic differences in prevalence, awareness, control and self-management of hypertension among four minority ethnic groups, Na Xi, Li Shu, Dai and Jing Po, in rural southwest China. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2017;31(6):388–394. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuspidi C., Meani S., Lonati L., et al. Prevalence of home blood pressure measurement among selected hypertensive patients: results of a multicenter survey from six hospital outpatient hypertension clinics in Italy. Blood Pressure. 2005;14(4):251–256. doi: 10.1080/08037050500210765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dymek J., Skowron A., Polak W., Golda A. Assessment of knowledge and skills of patients with hypertension related to self-measurement of blood pressure (SBPM) Arterial Hypertension. 2015;19(1):39–44. doi: 10.5603/ah.2015.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flacco M. E., Manzoli L., Bucci M., et al. Uneven accuracy of home blood pressure measurement: a multicentric survey. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2015;17(8):638–643. doi: 10.1111/jch.12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gohar F., Greenfield S. M., Beevers D. G., Lip G. Y. H., Jolly K. Self-care and adherence to medication: a survey in the hypertension outpatient clinic. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008;8(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H., Li G., Arao T. Prevalence rates of self-care behaviors and related factors in a rural hypertension population: a questionnaire survey. International Journal of Hypertension. 2013;2013:8. doi: 10.1155/2013/526949.526949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J., Han H. R., Song H., Lee J., Kim K. B., Kim M. T. Compliance with home blood pressure monitoring among middle‐aged Korean Americans with hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2010;12(4):253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melnikov S. Differences in knowledge of hypertension by age, gender, and blood pressure self-measurement among the Israeli adult population. Heart & Lung. 2019;48(4):339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merrick R. D. O. K., Hamdy R. C., Landy C., Cancellaro V. Factors influencing the accuracy of home blood pressure measurement. Southern Medical Journal. 1997;90(11):1110–1114. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milot J.-P., Birnbaum L., Larochelle P., et al. Unreliability of home blood pressure measurement and the effect of a patient-oriented intervention. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2015;31(5):658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell C. M., Cohen L. W., Viera A. J., Sloane P. D. Hypertensive patients’ use of blood pressure monitors stationed in pharmacies and other locations: a cross-sectional mail survey. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8(1):p. 216. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naik D. A., Kallen A. M., Walder L. A., Street L. R. Improving hypertension control in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communication. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1361–1368. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.724005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ragot S., Sosner P., Bouche G., Guillemain J., Herpin D. Appraisal of the knowledge of hypertensive patients and assessment of the role of the pharmacists in the management of hypertension: results of a regional survey. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2005;19(7):577–584. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao V. N., Sheridan S. L., Tuttle L. A., et al. The effect of numeracy level on completeness of home blood pressure monitoring. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2015;17(1):39–45. doi: 10.1111/jch.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidlerová J., Filipovský J., Wohlfahrt P., Mayer O., Cífková R. Availability and use of home blood pressure measurement in the Czech general population. Cor et Vasa. 2014;56(2):e158–e163. doi: 10.1016/j.crvasa.2014.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi D., Li J., Wang Y., et al. Association between health literacy and hypertension management in a Chinese community: a retrospective cohort study. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2017;12(6):765–776. doi: 10.1007/s11739-017-1651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan N. C., Khin L. W., Pagi R. Home blood-pressure monitoring among hypertensive patients in an Asian population. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2005;19(7):559–564. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tirabassi J., Fang J., Ayala C. Attitudes of primary care providers and recommendations of home blood pressure monitoring—docstyles, 2010. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2013;15(4):224–229. doi: 10.1111/jch.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tekin A., Yunus E., Ulver D., et al. Use of home sphygmomanometers in Turkey: a nation-wide survey. Hypertension Research. 2011;35(3):356–361. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyson M. J., Mcelduff P. Self-blood-pressure monitoring—a questionnaire study: response, requirement, training, support-group popularity and recommendations. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2003;17(1):51–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uzun S., Kara B., Yokuşoğlu M., Arslan F., Yilmaz M. B., Karaeren H. The assessment of adherence of hypertensive individuals to treatment and lifestyle change recommendations. Anadolu Kardiyoloji Dergisi. 2009;9(2):102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viera J. A., Tuttle A. L., Voora A. R., Olsson A. E. Comparison of patients’ confidence in office, ambulatory, and home blood pressure measurements as methods of assessing for hypertension. Blood Pressure Monitoring. 2015;20(6):335–340. doi: 10.1097/mbp.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y., Wang Y., Gu H., et al. Use of home blood pressure monitoring among hypertensive adults in primary care: minhang community survey. Blood Pressure Monitoring. 2014;19(3):140–144. doi: 10.1097/mbp.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bachmann L. M., Steurer J., Holm D., Vetter W. To what extent can we trust home blood pressure measurement? A randomized, controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2002;4(6):405–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.00953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binstock M. L., Franklin K. L. A comparison of compliance techniques on the control of high blood pressure. American Journal of Hypertension. 1988;1(3_Pt_3):192S–194S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.3.192s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brennan T., Spettell C., Villagra V., et al. Disease management to promote blood pressure control among African Americans. Population Health Management. 2010;13(2):65–72. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeJesus R. S., Chaudhry R., Leutink D. J., Hinton M. A., Cha S. S., Stroebel R. J. Effects of efforts to intensify management on blood pressure control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a pilot study. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2009;5:705–711. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Figar S., Galarza C., Petrlik E., et al. Effect of education on blood pressure control in elderly persons. American Journal of Hypertension. 2006;19(7):737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fung C., Wong W., Wong C., Lee A., Lam C. Home blood pressure monitoring: a trial on the effect of a structured education program. Australian Family Physician. 2013;42(4):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green B. B., Cook A. J., Ralston J. D., et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(24):2857–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haynes R. B., Gibson E., Hackett B., et al. Improvement of medication compliance in uncontrolled hypertension. The Lancet. 1976;307(7972):1265–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kauric-Klein Z., Artinian N. Improving blood pressure control in hypertensive hemodialysis patients. CANNT Journal. 2007;17(4):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim K. B., Han H.-R., Huh B., Nguyen T., Lee H., Kim M. T. The effect of a community-based self-help multimodal behavioral intervention in Korean American seniors with high blood pressure. American Journal of Hypertension. 2014;27(9):1199–1208. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maciejewski L. M., Bosworth B. H., Olsen K. M., et al. Do the benefits of participation in a hypertension self-management trial persist after patients resume usual care? Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2014;7(2):269–275. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.113.000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magid D. J., Ho P. M., Olson K. L., et al. A multimodal blood pressure control intervention in 3 healthcare systems. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2011;17(4):e96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morgado M., Rolo S., Castelo-Branco M. Pharmacist intervention program to enhance hypertension control: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2011;33(1):132–140. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9474-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nessman D. G., Carnahan J. E., Nugent C. A. Increasing compliance: patient-operated hypertension groups. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1980;140(11):1427–1430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.140.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ogedegbe N. G., Tobin E. J., Fernandez E. S., et al. Counseling African Americans to control hypertension: cluster-randomized clinical trial main effects. Circulation. 2014;129(20):2044–2051. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.006650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Victor R. G., Ravenell J. E., Freeman A., et al. Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men: the BARBER-1 study: a cluster randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(4):p. 342. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yi S. S., Tabaei P. B., Angell Y. S., et al. Self-blood pressure monitoring in an urban, ethnically diverse population: a randomized clinical trial utilizing the electronic health record. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2015;8(2):138–145. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.114.000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoo H. J., Park M. S., Kim T. N., et al. A ubiquitous chronic disease care system using cellular phones and the internet. Diabetic Medicine. 2009;26(6):628–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zillich A. J., Sutherland J. M., Kumbera P. A., Carter B. L. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study) Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(12):1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nielsen J., Shrestha A., Neupane D., Kallestrup P. Non-adherence to anti-hypertensive medication in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 92443 subjects. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2017;31(1):14–21. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 3: quality assessment of the selected interventional studies.