Dear editor,

We read with great interest the recent studies by Xu et al. and Yang et al. in this journal,1 , 2 both depicting the computed tomographic (CT) imaging features of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). In consideration of this pandemic, declared by WHO in 9 March 2020, threatening the public health worldwide, these results provided detailed imaging information of COVID-19 and favored the effective diagnosis.

Xu et al. reported 50 patients with confirmed COVID-19 and found that the CT imaging on admission mainly presented patchy ground glass opacities in the peripheral areas under the pleura and infiltration of bilateral lower lobes.1 Besides, severe and critically ill patients were significantly older than either mild or common patients, and had significantly more infected lobes. It was consistent with the previous study that severe and critically ill cases were older,3 , 4 and also suggested that older patients could have more abnormality in CT imaging. Yang et al. reported the CT imaging of 149 confirmed patients with mild infection from the perspective of pulmonary segments.2 The main pattern of CT abnormality was multifocal peripheral ground glass or mixed opacity with predominance in the lower lung, among which lung segments 6 and 10 were mostly involved.

A series of studies on COVID-19 CT imaging, with difference in sampling scale, study design and description perspective, were also reported. Earlier, two articles from Wang et al. and Guo et al. reporting all-round clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients distributed short context on the CT presentation.3 , 4 Among them, Wang et al. enrolled 138 patients infected during hospitalization including 36 critically ill cases and 102 non-critically ill cases. Bilateral distribution of patchy shadows and ground glass opacity, as the hallmark of CT scan, were seen in all patients.4 The study of Guo et al. involved a nationwide sampling of 1099 COVID-19 patients. 167 severe cases and 808 non-severe cases received CT scan and the main abnormality was also ground-glass opacity and bilateral patchy shadowing.3 No further in-depth description was depicted. However, Chung et al., specialized in imaging, reported 21 cases and pointed that 57% patients were manifested with ground glass opacities and 33% presented peripheral distribution. But no difference was seen regarding the lesion distribution on lobes, perhaps due to the limited number of patients. Lung cavitation, discrete pulmonary nodules, pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy were absent.5 Song et al. enrolled 51 patients and pinpointed on different forms of lung lesion that pure ground grass opacity (pGGO) in 77% patients, GGO with reticular and/or interlobular septal thickening in 75% patients, GGO with consolidation in 59% patients and pure consolidation in 55% patients. Furthermore, there were 90% patients with lesions distributed in the lower lobes, 86% patients with lesions distributed in the lung periphery and 80% patients with lesions distributed in the posterior part of the lung.6 Shi et al. focused on temporal changes throughout the disease course and stratified 81 patients on the interval from symptom onset to first CT scan. They indicated the rapid evolution within 1–3 weeks from focal unilateral to diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities that progressed to or co-existed with consolidations.7

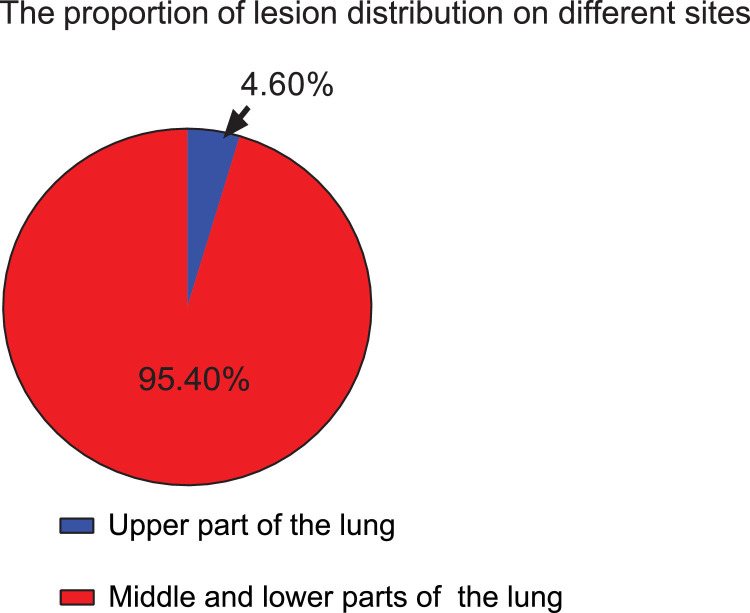

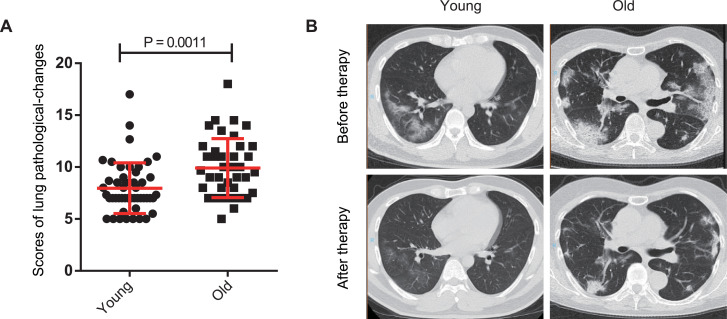

These findings concurred with our retrospective study. We enrolled 165 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (confirmed by RT-PCR) from January 2 to February 5, 2020 in 5 different hospitals. All these 5 hospitals were designated hospitals for treating COVID-19, including one outside Wuhan city and one outside Hubei province. All patients received chest CT scan on admission. For all lung lesion, we found that 95.4% was located in the middle and lower parts of lung while only 4.6% in the upper part (Fig. 1 ). We then introduced a CT imaging score system to quantify the pathological changes of COVID-19 patients (Table 1 ). To reveal the relationship between age and CT imaging abnormality, we classified these patients into 3 groups and compared the young group (with age ≤40 years) with the old (with age ≥60 years). Of note, the patients in the old group had significantly more severe CT imaging (Fig. 2 A). The representative CT imaging of the young and the old on admission were listed in Fig. 2B. Radiographic improvement was obviously seen after effective therapy.

Fig. 1.

The lesion distribution on different sites was calculated based on all lung lesions. The result showed the proportion in the upper part of the lung and the middle and lower parts of the lung.

Table 1.

CT imaging score system to quantify the severity of COVID-19 patients.

| No. | Performance | Score |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | Unbilateral patchy shadow or ground glass opacity | 5 |

| (2) | Bilateral patchy shadow or ground glass opacity | 7 |

| (3) | Diffuse changes for (1) or (2) | 2 |

| (4) | Unbilateral solid shadow, striped shadow | 2 |

| (5) | Bilateral solid shadow, striped shadow | 4 |

| (6) | Unbilateral pleural effusion | 2 |

| (7) | Bilateral pleural effusion | 4 |

| (8) | Increased or enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes | 1 |

Fig. 2.

A. The scores of the young (≤40 years) and the old (≥60 years) were evaluated by analyzing the images of the chest CT scan. B. The representative CT images of the young and the old patients. These CT images were taken before or after therapy, respectively.

The number of COVID-19 patients is still surging in multiple areas around the world. By 22 March 2020, a total of 222,707 cases were diagnosed outside China. Given the relative scarcity and false negative result of nucleic acid testing, the data may be far from the true reality. Currently the detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid serves as the basis for diagnosis. It was reported that the sensitivity of RT-PCR was lower than that of CT because it can be influenced by the accuracy of test kit, the viral load, and the quality of specimen sampling.8 COVID-19 features attacking on the respiratory system, where CT imaging enjoys its accuracy and convenience in real-timely reflecting the lung condition. Shi et al. also confirmed the CT manifestations in asymptomatic patients preceded the symptom onset. Thus, CT could greatly compensate RT-PCR in diagnosis, especially for patients with false-negative RT-PCR results.

In conclusion, a cluster of studies suggest the primary pattern on CT imaging of COVID-19 pnuemonia is GGO of different subtypes, with the distribution prominence in lower, posterior and peripheral lung, which can quickly change during hospitalization. Old patients have severe presentation of CT imaging. Therefore, CT scan as an important tool deserves attention in disease diagnosis, which will facilitate the patients sorting on severity and the early intervention of quarantine or treatment, dependent on the clinical manifestation. Given the improved efficiency of CT imaging evaluation with artificial intelligence and big data, it is imperative to collect CT imaging as comprehensive as possible enabling the in-depth learning. Evaluation of CT imaging through telemedicine could probably relief the imbalance of medical resources to some extent. Despite the available information, more extended detailed studies on CT imaging is still needed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

All the authors participated in generating the idea. Zili Zhang and Yin Shen wrote the initial version of the letter. Desheng Hu, Haijun Wang and Lei Zhao critically reviewed and edited it with their comments.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31770983 and 81974249 to DH)

References

- 1.Xu Y.H., Dong J.H., An W.M., Lv X.Y., Yin X.P., Zhang J.Z. Clinical and computed tomographic imaging features of novel coronavirus pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020 Feb 25 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.017. PubMed PMID: 32109443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang W., Cao Q., Qin L., Wang X., Cheng Z., Pan A. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, china. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016. PubMed PMID: 32112884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. PubMed PMID: 32109013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. PubMed PMID: 32031570Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC7042881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295(1):202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. PubMed PMID: 32017661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song F., Shi N., Shan F., Zhang Z., Shen J., Lu H. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. PubMed PMID: 32027573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., Cao Y., Alwalid O., Gu J. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Y., Zhang H., Xie J., Lin M., Ying L., Pang P. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. PubMed PMID: 32073353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]