Abstract

Prepping is a practice of anticipating and adaptating to impending conditions of calamity, ranging from low-level crises to extinction-level events. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which preppers consider a 'mid-level' event, and which many of them were well-prepared for, makes clear that scholarly attention to prepper's motivations and methods is both timely and valuable. Drawing from a three-year ethnographic research project with preppers, this paper traces the activity of a single bunker builder who has constructed a technically sophisticated private underground community. Supplemented by additional fieldwork, the paper argues that the boltholes preppers are building in closed communities built to survive the collapse of society, order, and even the environment itself, refract the seemingly irresolvable problems we are failing to address as a species. In the prepper ideology, faith in adaptation has supplanted hope of mitigation, making contemporary bunkers more speculative than reactionary and more temporal than spatial. The bunkers preppers build are an ark to cross through a likely (but often unspecified) catastrophe; they are a chrysalis from which to be reborn - potentially even into an improved milieu.

Keywords: Preppers, Dread, Bunkers, Survival Condo, Underground, COVID-19

1. The Survival Condo

‘The sharper our consciousness of the world’s infinity, the more acute our awareness of our own finitude.’

Nestled amongst Kansas cornfields in a landscape devoid of any noticeable natural topography, a verdant mound can be seen from a dirt road. It is surrounded by military-grade chain link fence and watched over by a large wind turbine and a camouflaged security guard with an assault rifle. Looking closely, one would notice a semi-subterranean concrete pill box perched atop the mound, flanked by cameras. What lies underneath is a bunker that is both unassuming and unassailable.

One might assume that this is a covert government installation, and indeed at one time this would have been the case. However, is was not a bunker built to house or hide citizens of the state or to protect the politicians who ordered its construction. It was an Atlas F missile silo, built in the early 1960s at a cost of approximately $15 million to United States taxpayers. It was one of 72 ‘hardened’ missile silo structures built from concrete mixed with an epoxy-based resin, protecting a nuclear-tipped Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICMB) one hundred times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The function of this bunker was therefore ‘both defensive and offensive… based on a twofold logic of protected interiors and outward aggressiveness’ (Monteyne, 2011: xix). Although this bunker was out of sight and out of mind to the average US citizen, it played a crucial role in a geopolitical agenda of extinction-level significance. Bunkers like these were, and are, as Ian Klinke has suggested, biopolitical spaces of extermination (Klinke, 2018: Ch 5).

However, that was then; that was the Cold War, and this bunker in Kansas is no longer owned by the government. In 2008, it was purchased by Larry Hall, an ex-government contractor, property developer, and doomsday ‘prepper’. Preppers are people who anticipate and actively attempt to adapt for what they see as probable or inevitable impending conditions of calamity, ranging from low-level crises to extinction-level events, where ‘food and basic utilities may be unavailable, government assistance may be non-existent, and survivors may have to individually sustain their own survival’ (Mills, 2018: 1).

Since purchasing the silo in 2008, Larry Hall has transformed it into a 15-story inverted tower block, a geoscraper. A community of up to 75 individuals can weather a maximum of five years inside this subterranean, sealed, self-sufficient luxury habitation. When the event passes, residents expect to be able emerge into the post-apocalyptic world (PAW, in prepper parlance) to rebuild (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

A cross-section render of the converted Atlas F Silo (image courtesy of Survival Condo).

The temporality of the bunker therefore plays a crucial role in its materiality, since it functions as a ‘vehicle that puts one out of danger by crossing over mortal hazards’ (Virilio, 1994: 46) Some residents look forward to that time because the dreadful anticipation of catastrophe will have finally been ruptured, because time inside the bunker might offer them an opportunity for self-improvement, or because the PAW may prove more fruitful, fecund, and capacious than the world we currently inhabit. The Survival Condo, and hundreds of analogous experiments in communal bunkered living across the world, are thus built to function as a temporal bridge affording re-emergence into a new, and potentially improved, milieu, political situation, or environment after a disaster. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which many preppers were well prepared for, offers a unique opportunity to assess the motivations and methods of preppers. Ethnographic research about prepping dispels some of the unflattering media representations around the global prepper community and suggest many of thier practices may become normalised in the wake of the disaster. Thus, events like the 2020 pandemic offer fresh opportunities for new scholarship on the practice.

This article engages with the subterranean geopolitics of preppers whose goal it is to retain security, sustainability and luxury across times of anthropogenic turmoil. I do so here in the context of a walking interview through Survival Condo with Larry Hall. This single case study has been selected from a three-year ethnographic research project on the culture, politics and practises of so-called ‘doomsday preppers’ where nearly a hundred project participants were met in the course of research across six countries. The results of that project will be published elsewhere (Garrett, 2020). However, relevant anonymised quotes from other field sites have been included in support the argument above.

Prepping takes place at a range of scales (see Peterson, 1984). Most existing ethnographic research into the practice, such as the work of Huddleston (2016), Mills, 2017, Mills, 2018, Mills, 2019, and Barker (2019) engaged with respondents who were prepping for ‘low-level’ events. The focus of this study was on the other end of the scale, whereas Kabel and Chmidling (2014: 258) write, ‘…modern day preppers build or purchase underground bunkers in which they can safely wait out the impending unrest and resurface at an undetermined point in the future’. As a result, this research focuses on the materiality and temporality of space as much as on practices, since it involved working with preppers who are not just stockpiling goods but actively constructing new architectures for disaster. Before delving into these spaces, however, it is important to sketch out a social history of prepping.

2. Prepping as a social practice

The political commentator Lewis Lapham suggests the first nuclear test on 16th July 1945 was the genesis of a new era marked by the novel human ability to destroy not just ourselves but the entire planet; when ‘powers once assigned to God passed into the hands of physicists and politicians, what had been divine became human…’ (Lapham, 2017: 18). For Lapham, the dawn of the nuclear age corresponded to a powerful affective increase in inveterate dread, for not only did atomic weapons seem to embody transcendent power, they were a planetary force, a force that we simultaneously wielded and experienced as beyond our control and understanding. Nuclear dread was predicated on the possibility of extinction and as Thacker (2012: 144) writes, ‘human extinction can never be fully comprehended, since it’s very possibility presupposes the absolute negation of all thought.’ In other words, the possibility triggering our own annihilation contradicted human instincts, causing mass panic and apathy in equal measure (see Bourke, 2006: 191).

Meanwhile, politicians were busy building bunkers to protect themselves from what they had unleashed. In 1956, President Eisenhower hosted the North American Summit Conference at the Greenbrier Resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. Two years later, construction began underneath the hotel on large subterranean government bunker. Project Greek Island – as the 112,000-square-foot facility was code-named – was designed to house as many as 1100 people including 535 members of congress and their aides (Vanderbilt 2002: 135). It featured 18 dormitories, industrial kitchen facilities, a hospital, document vault, power systems, and a television broadcast studio. When President Kennedy took power soon after and became aware of just how proximal the nuclear threat was, he asked Congress to fund the construction of blast-resistant shelters for the general public. This initiative was squarely rejected in favour of a more modest programme focussed on locating and identifying areas that could be used as radiation fallout shelters.

In was against this backdrop that in a nationally televised speech in July 1961, Kennedy told the American people that they had the ‘sobering responsibility to recognize the possibilities of nuclear war’ (Szasz, 2007: 15). Two months later, Life Magazine’s cover story gave instructions on how to survive nuclear fallout. A chilling letter from President Kennedy that ran alongside the article urged Americans to learn how to build fallout shelters in their backyards and millions were built. According to sociologist Andrew Szasz (2007: 17):

Demand for shelters boomed. Local contractors reinvented themselves and miraculously became, overnight, fallout shelter specialists. Sears planned to begin selling a prefab shelter kit that had been featured in the article in Life. Companies rushed to market shelter supplies.

This period, which is sometimes referred to as the 'first doom boom', is of crucial geopolitical significance because it marked an abandonment of the social provision of protection by the US government in the context of potential a potential nuclear genocide. As Ian Klinke and I have written elsewhere, these ‘bunkers were spaces of exception, where democratic states could morph into autocracies in times of war by making the decision to sacrifice the polis from this space of protection’ (Garrett and Klinke, 2018: 1071). This potential for horror was calculated in the totally inhuman term ‘megabodies’: a stand in for one million dead citizens (Situationist International, 2007). Unlike the public shelters of Europe in World War II, or the concealed hardened architectures Switzerland built during the Cold War (Mariani, 2009), which were literally constructed to shelter every citizen, United States bunkers were constructed not for citizens but for government elites.

In the same year that Kennedy gave the speech that triggered the fallout shelter panic, the Minuteman Militia was formed by Robert DePugh. The Minutemen were an anti-Communist organization that promoted preparation for guerrilla warfare inside America by training in survival skills, hunting, marksmanship, and by working towards self-sufficiency from government infrastructure. This was the seed for a related social movement we now call ‘survivalism’ (see Mills, 2017: 38). According to historian Philip Lamy (1996: 14):

Survivalism is a loosely structured yet pervasive belief system and set of practices focusing on disaster preparedness. […] [Survivalists] stockpile water, canned goods, medical supplies, and guns. Still others purchase isolated rural property, enroll in survival training programs, or belong to survival communities or organizations. Survivalists are people who are prepared to survive the devastation…

By the 1980s up to a million Americans were actively serving or sympathetic to survivalist militias and as many as three million Americans were involved in survivalist practices (Hamm, 1997, Mills, 2017). Survivalism also became a billion-dollar industry (Lamy, 1996: 69). For early survivalists, paving a path for escape was central. They would perform evasion until they had perfected it, building up the necessary skills, based around a return to crafting and making, to outlast the collapse of the society of control they had already abandoned.

Since that time, not only has the threat of nuclear annihilation not receded, we are now faced with the even more insurmountable threat of the climate crisis, which, like the possibility of nuclear extinction, we have caused. Additionally, many people fear the pace of technological acceleration, including recent developemnts in artificial intelligence, gene editing, and systems of surveillance (which potentially preclude evasion entirely). The natural disasters and pandemics of our past have only become more threatening as global populations have urbanised and densified. As a result of these, and many other, new sources of angst, prepping for disaster is once again a widespread cultural practice.

This infolding of prepping practices into everyday life has also been concurrent with the aging of infrastructural systems, the privatisation of public services, and cuts to social ‘safety nets’ under neoliberal ideologies in much of the western world (Garrett et al., 2020). Much prepping, unlike survivalism, is not based on conspiracy but experience, and there is a ‘distinct difference between such fringe elements of the past and the average prepper of today’ (Huddleston, 2016: 241). As Mills writes, contemporary preppers include a wider demographic spectrum of society, and many preppers are not prepping for an apocalyptic event, they are simply interested in securing ‘nutrition, hydration, shelter, security, hygiene and medicine’ during medium- to long-term periods of infrastructural breakdown (Mills, 2019: 1). The collapse of supply lines, international travel and trade routes, economic systems, and social order during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic was a prime example of the kind of breakdown preppers were anticipating and had prepared for. The majority of contemporary prepping is not predicated on fringe ideologies, it is built around ‘precautionary fears of disaster… aligned with areas of relatively popular political sentiments’ (Mills, 2019: 2).

Right-wing media shock-jocks in the United States, including ‘Alex Jones, Glenn Beck and Sean Hannity all advocate doomsday prepping to their audience’ (Kelly, 2016: 98). On the other side of the political spectrum, a Southern California National Public Radio station started airing a show called ‘The Big One’, which mixed dramatic performances and ominous music to instil listeners with fear about the next big quake before turning to a word from the podcast’s sponsor – a company that sells three-day emergency bug out bags for $495. Preppers activities are therefore partly inspired by interpretations of disaster risks shaped by the content of mainstream news media. This has worked to ‘normalise’ prepping, since the media itself is propagating constant ‘fear laden assessments of economic policy, health care reform, and security risks to a wide a receptive audience’ (Mills, 2019, Mills, 2018). A global disaster having finally arrived, it is likely that prepping will become even more widepread and socially acceptable.

Kelly (2016: 98) estimates contemporary prepping to be a $500-million-a-year industry, following estimates from a 2013 New York Times article (Feuer, 2013). More recent estimates suggest that 3.7 million Americans actively identify as preppers (Stec, 2016). It is a practice that has expanded well beyond the United States. Campbell et al. (2019: 799) write that prepping is ‘an increasingly mainstream phenomenon, driven not by delusional certainty, but a precautionary response to a generalised anxiety people have around permanent crisis.’ Klein (2017: 351) suggests that even ‘in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street… high-end survivalists are hedging against climate disruption and social collapse by buying space in custom-built underground bunkers…’ Indeed, prepping is an even bigger business than its survivalist forbearer. We are in the midst of a second billion-dollar -a-year ‘doom boom’, with sales of preserved food alone surging over 700% since 2008 (Mills 2018: 2). In the United States, preserved ‘survival food’ is even being been stocked by major retailers such as Costco, Kmart and Bed, Bath & Beyond (Mills 2019: 2).

Scholarly research has yet to catch up with this ‘second doom boom’. Despite the fact that a full 1.13% of the United States population, and millions more beyond those borders, are prepping, academic research around the topic is scant. What does exist is often superficial and naïve, being based wholly on analysis of popular representations.

Foster’s (2014) book Hoarders, Doomsday Preppers, and the Culture of Apocalypse, for instance, was based on watching the Doomsday Preppers ‘reality’ TV show on the National Geographic Channel. What Foster ultimately offers is a shallow and ambiguous caricature of the community that bears little reality of the everyday lives of preppers and conflates their activities with hoarding, which makes little sense, given how much time preppers spend carefully organizing and streamlining life-saving stockpiles. In another paper devoted to what was termed the ‘man-poclypse’, Kelly writes that that prepper culture is infused with ‘…feelings of male alienation [that] translate into preparations for an uncertain future’ (Kelly, 2016: 96), another assumption based on watching television which is quickly undermined by fieldwork, where it becomes clear women are often the driving force behind preparations. Finally, Kabel and Chmiding (2014) conducted what they called a ‘netnography’ – a portmanteau for ‘Internet ethnography’ – on prepper web forums. Though their study relied on first-person accounts rather than third-person representations, ethnographic research undertaken into internet posturing, particularly when posted anonymously, is no substitute for on-the-ground fieldwork.

The most robust research on contemporary prepping to date has been undertaken by Chad Huddleston, Michael Mills, and Kezia Barker. Huddleston conducted ethnographic research with a small group of socially-minded preppers in Missouri called the ‘Zombie Squad’. This public-facing grassroots organisation focusses on ‘self-organising in order to support established systems in order to withstand disturbances’ (Huddleston, 2016: 240). The research undertaken by Mills was larger in scope, spanning eighteen US states and including thirty-nine people. Mills found that partisan politics play a key role in the ideologies undergirding prepping practices and provided grounded evidence regarding prepper's anxieties about the unknown (Mills, 2018, Mills, 2019). Most recently, Barker's extensive research, which involved in-depth interviews, participant observation of prepper meetups, and online analysis, provocatively suggests that in becoming resilient citizens, preppers are 'recuperating the agency of future temporalities, by finding empowerment, pleasure and vitality in moving closer to their metabolic vulnerability' (Barker, 2019: 11). All three researchers lament the lack of scholarly engagement with prepper communities, but Mills in particular calls for further research ‘focussed on the movement’s broad political character or guiding ideologies’ (Mills, 2019: 6). This paper is an answer to that call.

During an interview with Larry Hall inside the Survival Condo, he explained that, ‘The whole idea was that we could build a green doomsday structure that someone can use as a second home that also happens to be a nuclear hardened bunker’ (Fig. 1). He continued:

This is a safe, self-contained, sustainable experiment in architecture – it’s a subterranean equivalent of the ASU (Arizona State University) Biosphere 2 project. This is a completely closed system. People try to build systems like this on their farms and they get infiltrated by bugs, they get crop burn from solar radiation and they get rain and wind damage. We’ve removed all those factors. We need to think about space travel and things like that. This bunker is good practice for living in those closed systems.

Fig. 1.

The entrance to the Survival Condo (photo by author).

Bunkers like Survival Condo may occupy the same physical and material space as earlier government installations, but their geopolitical framing differs drastically, reflecting contemporary social and political anxieties which are increasingly unmoored from particulars. They are also, of course, distinctly private endeavours that seek to use renewable technologies to decrease dependance on state infrastructure. These bunkers are examples of private actors seizing and controlling volumetric territory (Adey, 2013, Bridge, 2013, Elden, 2013, Graham, 2016, Graham and Hewitt, 2012). Survival Condo is part of a growing desire to ‘prep’ in the most sustainable way possible without necessarily forgoing the comforts of late capitalism. Each of these developments challenges our notions of what constitutes a bunker (see Garrett and Klinke, 2018), but more importantly provide a baseline for understanding the ideologies driving their construction. This is a worldview, I argue in the following section, steeped in dread.

3. An accident brewing

‘We are reaching the limits of our ecosystem, and we are therefore reaching a phase of permanent catastrophe.’

The ‘objectless anxiety’ (Mills, 2018: 7) at the core of contemporary prepping, in contrast to the specific nuclear anxieties driving survivalism, is a ‘sense of existential dread we experience on many fronts’ (Campbell et al., 2019: 798), without ‘much specification of particular risks’ (p. 801). The inability to know which disaster is being prepared for, or at what scale, coupled with the perceived inevitability of catastrophe, has created the palpable affect of dread that preppers are acting on. Dread differs from anxiety in that it is about the future rather than the present and differs from fear because it stems from a danger not immediately present or even discernible. It is an anthropogenic practice refracting ‘the limits of explanation’ (Miéville, 2014: 58).

Sigmund Freud circled around this problem in A General Instruction to Psychoanalysis, where he suggested cleaving real fear from neurotic fear, with neurotic fear being,

…a general condition of anxiety, a condition of free-floating fear as it were, which is ready to attach itself to any appropriate idea, to influence judgment, to give rise to expectations, in fact to seize any opportunity to make itself felt. We call this condition “expectant fear” or “anxious expectation.” Persons who suffer from this sort of fear always prophesy the most terrible of all possibilities, interpret every coincidence as an evil omen, and ascribe a dreadful meaning to all uncertainty. Many persons who cannot be termed ill show this tendency to anticipate disaster. We blame them for being over-anxious or pessimistic (Freud, 1920: 689–690).

What Freud is suggesting here, in a passage that almost sounds like it was written about preppers – and society’s response to them – is that it makes far more sense to see the ‘neurotic’ or delirious individual as a person rationally responding to an uncertain situation. Their tendency to ‘ascribe a dreadful meaning to events’ may be triggered external situations as much as internal psychological makeup. These feelings are vocalised by preppers. As one bunker builder interviewed for this project explained:

‘For me, keeping my family safe and secure each and every day is what I focus on… For the most part, safety is an illusion. Your best chance at actually being safe however is when you take control of the parameters.’

Rather than becoming paralysed by dread, preppers act, even if those actions do not always look wholly comprehensible to others. As Adey and Anderson (2012: 101) write, ‘preparedness is… a series of discourses, practices and technologies’ [in which] ‘uncertainties over threat are made legible by transforming those threats into calculable risk…’. The incalculable dread outside the blast door can be rendered calculable inside the bunker through careful preparation and planning.

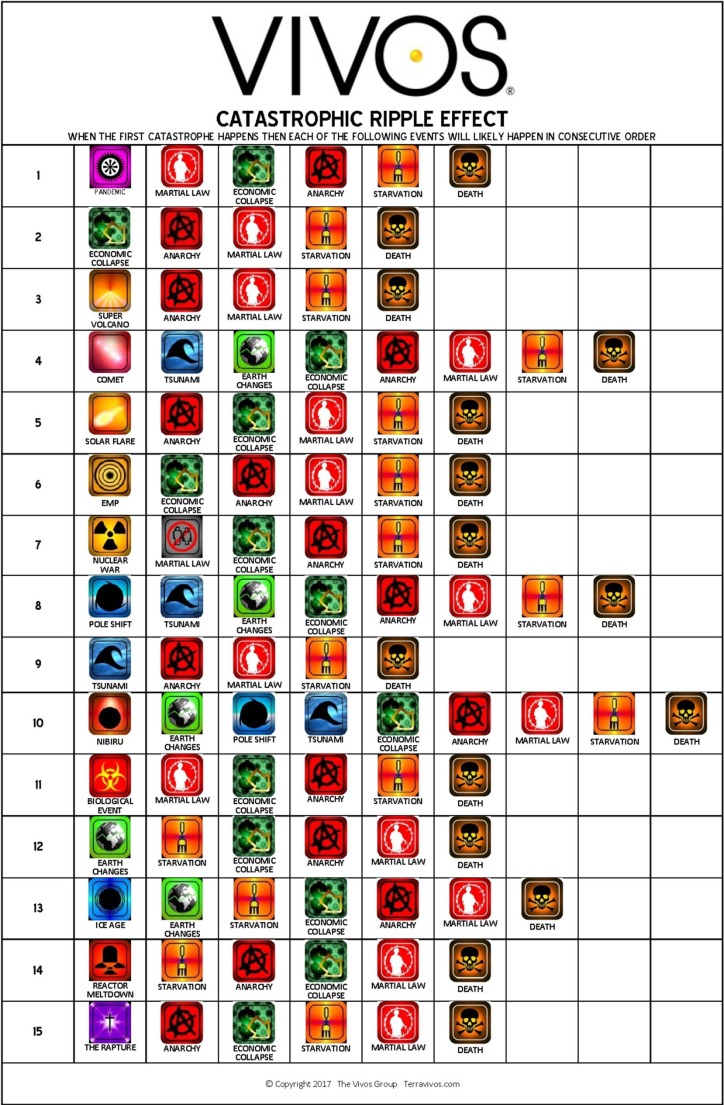

The material qualities of the bunker have morphed to keep pace with external threats. In the past, bunkers were built by governments for specific situations, be they aerial bombing or nuclear attack. In contrast, contemporary preppers are also organising for a wider range of threats than during the hot and cold wars of the 20th-century. People are now preparing a ‘catastrophic ripple effect’ – a cascade of existential horror brought on by connectivity, speed, hyperbolic partisan media, resource depletion and, ultimately, fragility brought on by overpopulation, globalisation, and technological advancement (see Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

The catastrophic ripple effect (image courtesy of the Vivos Group).

This sentiment echoes the work Paul Virilio, who has suggested that ‘all technical objects brought about accidents that were specific, local, and situated in time and space. The Titanic leaked in one place, while the train derailed in in another. [Now] we have created the possibility of an accident that is no longer particular but general’ (Virilio, 1999: 92–93). Preppers follow Virilio in thinking that ‘there is an accident brewing that would occur everywhere at the same time’ (Virilio, 1999: 37–38). This unspecified but terrible disaster is what they are building for, or hedging against, to follow Naomi Klein. In this light, the decision to ‘prep’ against seemingly boundless and uncontrollable global forces is an existential concern with material manifestations. What is harder to explain is the desire some preppers exhibit to ‘just hit the reset button now’, as one interviewee put it.

Søren Kierkegaard’s 1844 The Concept of Dread serves as a crucial reference in mapping existential dread as an inchoate ‘sweet feeling of apprehension’ about the future, an anticipatory state that stems from ‘freedom’s reality as possibility for possibility’ (Kierkegaard, 1968: 38). Dread is a dialectical sense of foreboding about an ambiguous object (p. 39) that we wish to see manifest because the possibility of its consequence is the possibility of freedom (p. 40–41). Whereas we are anxious about people, objects, events and things, dread is an ontological orientation we find ourselves in which cannot be attached to an object. The abyss that opens with dreadful awareness is alluring in promise. Trying to synthesise the affect creates a ‘debility in which freedom swoons’ (p. 55). According to Kierkegaard, dread does not ‘tempt as a definite choice, but alarms and fascinates with its sweet anxiety. Thus, dread is the dizziness of freedom which occurs when… freedom then gazes down into its own possibility, grasping at finiteness to sustain itself’ (p. 55).

More recently, Zygmunt Bauman has described the state of ‘liquid fear’ enveloping contemporary society as a state of ‘unpredictable, unpreventable, incomprehensible [events] immune to human reason and wishes’ (Bauman, 2006: 149), words which were written almost 15 years prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, but which resonate powerfully now. This state of fear is founded on an acknowledgment of the limits of human knowledge and impossibility of achieving mastery over our environment, but also stem from a sense that our creations have exceeded us and that we lack the political will to reign them back in. In the context of climate change, species-jumping viruses, biological engineering, or the disposal of nuclear waste, for instance, the environment itself has become a technical problem constantly in need of upgrade and repair, so that we will forevermore live in a state of permanent catastrophe to be managed rather than avoided (De Cauter, 2004: 100). Every day, we are surrounded by a multitude of choices that seem inconsequential on a personal level and catastrophic at the level of the species.

Reflecting on the ‘dizziness of freedom’ the dread inspires, China Miéville argues that ‘dread is a sense of plenitude. A plenitude of whatever’ (Miéville, 2014: 55). In the same edited collection, Juha Van ’t Zelfde evocatively suggests that through the ‘dialectical coupling of caution and transgression, of paralysis and overdrive, dread allows us to imagine the world differently’ (Zelfde, 2014: back cover), offering us an alternative framing for seeing dread as a productive force. In this framing, dread is linked with millenarian apocalyptic ideologies of death and rebirth, where the frustration of choice results in a decision to fold to cosmic pressure and start again. The architecture of dread is thus also dialectical, in the sense that it promises both disaster and salvation. The bunker is built because ‘it is only at the instant when salvation is actually posited that this dread is overcome’ (Kierkegaard, 1968: 48). In the next section, I turn to a house that dread built: Survival Condo.

4. The architecture of dread

‘The problems with which my mind and body confronted are among those posed by life in a hermitically sealed capsule.’

Back in Kansas, I followed Larry Hall through one of the 16,000lbs blast doors nestled under the pillbox on the verdant hill into his 15-story geoscraper that can be 'locked down' at a moment's notice. He waved me over to the nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC) air filtration unit for the condo and explained that they had three military-grade filters each providing 2000-cubic feet per minute of filtration. He told me they ‘were $30,000 a pop. I put $20 million into this place and when you start buying military-grade equipment from the government you wouldn’t believe how quickly you get to that number.’

Hall’s team had drilled forty-five 300-foot deep subterranean geothermal wells and installed a reverse osmosis water system that uses hydrogen peroxide and colloidal silver to purify water before pumping it through UV sterilization and carbon paper filters. The system can filter 10,000 gallons of water a day into three electronically-monitored 25,000-gallon tanks. Power to the bunker is supplied by five different redundant systems. This is crucial, since as a life-support system, losing power would kill everyone in the facility. Hall elaborated,

‘We’ve got a bank of 386 submarine batteries with a life of 15 or 16 years. We’re currently running at 50–60 kW, 16–18 of which are coming from the wind turbine… However, we can’t do solar here… because the panels are fragile, and this is, after all, tornado alley. At some point we know that wind turbine is going to go too, I mean it won’t make it through five years of ice storms and hail, so we’ve also got two 100 kW diesel generators, each of which could run the facility for 2 ½ years.’

The Survival Condo has both private and communal areas, as you might find in any ‘mixed-use’ high-rise development. However, in this tower block, during full ‘lock down’ mode there can be no external support. It must function as a closed system, where people are kept both healthy and busy until they are able to emerge. Experiments in enclosed life-support systems conducted by the military (for submarines) and scientists (for spacecraft) have often neglected consideration of the sustainability of social systems after lockdown (Marvin and Hodson, 2016). Hall recognized that sustainability in the facility could not simply be about technical functionality. He opened another door to a 50,000-gallon indoor swimming pool verged by a rock waterfall, lounge chairs and a picnic table. It was like a scene from a resort, but without the sun (see Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

The pool inside the Survival Condo (image by author).

At the theatre and lounge level, we sat in leather recliners and watched a 4k screening of a 007 film. The cinema was connected to the bar, which was intended to act as ‘neutral ground’ for future residents. They had a beer keg system and one of the residents had provided 2600 bottles of wine from her restaurant to stock the wine rack. As he showed me this, Hall insisted that recreation, sharing, and community amongst the residents was as important to the facility’s design and management as the technical systems.

In this, the Survival Condo is a thoroughly modernist architectural project. Le Corbusier (1986 [1931]: 95, 240), who thought of buildings as machines for living in, wrote that ‘we must use the results of modern technical triumphs to set man (sic) free’. Though Le Corbuiser would have appreciated seeing people live above multi-story shopping malls connected by aerial skyways, creating what he called in The City of Tomorrow a ‘theoretically water-tight formula’ for urban planning, he would have been equally interested in the theoretically air-tight bunker, where waste has no place (see Pinder, 2006 for more on Le Corbusier’s architectural and geographic imagination). Given the severe limitations of underground living, anything extraneous must be eliminated. The entire building must be thought of as a single unit, where the actions of each resident inevitably effects all other residents. This of course is what makes the bunker more like a submarine journey than a tower block: the elimination of external infrastructural support. In the event of a major incident, the umbilical cord to the world on the other side of the blast doors would be snipped and the clock would start ticking to a resupply.

Private burrowing is not, of course, limited to bunkers. Journalists and academics have critically examined the ‘elite urban burrowing phenomenon’ (Graham, 2016: 313) taking place in global cities, where subterranean mega-basements, or what Wainwright (2012) calls ‘iceberg architecture’, cloak secure space behind banal façades. Atkinson and Blandy (2017: 109) suggest that the fortified architecture of contemporary ultra-secure homes tends toward two types: ‘spiky’ and ‘stealthy’, different architectural approaches ‘based respectively on fantasies of impenetrable castellation or the concealed or discreet presence of refuge…’ Burrowing is also not limited to the vertical. Stealthy additions can also be masked in more covert ways, as criminologist Kindynis (2020: 6) describes, where property owners have,

…hermetically sealed cells installed behind false walls or bookcases, complete with ballistic wall panels, backup power supplies, air filtration systems and satellite phones; designed to withstand threats ranging from sustained attacks from armed intruders to nuclear disaster (Kindynis, 2020: 6).

These forms of volumetric segregation purportedly create atomic social relations. Excavation is creating, according to Kindynis (2020: 4), ‘a fragmented archipelago of fortified and bunkerised residences.’ This archipelago is meant to result in the creation of ‘a capsular society… the phantasmagoric space of consumption and the fortress: the armoured enclave against the hostile world outside in a global capitalist society increasingly characterised by duality of rich and poor, inside and outside’ (De Cauter, 2004: 69, also see Minton, 2012).

On the other hand, in an era of surveillance dominated by a concerted push by Silicon Valley elites to eviscerate all forms of privacy, subterranea may be humanity’s last refuge against total transparency, at least for now (see Bishop, 2011 and Chambliss, 2020 on rendering the underground visible from space). One prepper interviewed suggested that the bunker he was building was the best escape plan possible within the confines of the geo. He told me, ‘we can’t build a celestial ark like Elon Musk, we can’t leave the earth, so we’re going to go into the earth. I’m building a spaceship in the earth.’

If the factory was the defining private architectural form of the early 20th century, and the fallout shelter the most iconic of the Cold War years, the skyscraper was the defining architecture of late neoliberalism. In the 21st century however, the private bunker has emerged as an unmistakable architectural form for our new dark age, ‘securing the futures of humanity under turbulent conditions in enclosed systems that have given up on fixing the world and insists on building a new one inside their confines within a permanent state of emergency’ (Marvin and Rutherford, 2018: 1145; Shapiro and David-Bird, 2017). As sustainable technologies and the collapse of the age of globalisation intertwine with unprecedented private abilities to excavate, a new subterranean politics of temporal resurrection is developing that is central to the ideology driving prepping acivities. Is it to this we turn in the final section.

5. Building for resurrection

‘Death, in this view, was no longer a philosophical problem; it was a technical problem.’

The word Apocalypse, from the Greek apokalyptein, is a crisis which brings about disclosure and thus is often a point for renewal. Apocalypse is not the end of the world but The End of the World as We Know It, or TEOTWAWKI, according to preppers. Apocalyptic thinking disrupts our sense that what we know and understand as immutable and timeless and often manifests when a culture and/or society become deeply entrenched in a particular way of life (Hall, 2009: 2–3). Apocalyptic thinking also, as its roots suggest, puts forth a temporal philosophy where if one can cross, through faith or preparedness, one can find renewal.

Throughout history, when humans have reached what seems to be a terminal phase, apocalyptic thinking surfaces, offering hope of survival. In the face of rapid and widespread change ‘…we live through the death of others, and their death gives meaning to our success: we are still alive’ (Bauman, 1992:10, emphasis in original). As Thacker (2012: 142) suggests, death and survival are what matters, because extinction is a meaningless tautology. A world without us in it does not include us considering the consequences of survival. The possibility of salvation, the freedom in making the choice to survive, and the potential satisfaction reaped from taking that leap of faith, is what prompted Keirkegaard to write in his journals that ‘dread is a desire for what one dreads, a sympathetic antipathy’ (Dru, 1938). This double-edge desire is the kernel of the resurrection temporality that drives contemporary millenarian ideologies.

One prepper building a large-scale bunker told me that ‘I imagine walking through the doors of [the bunker] when it’s finally finished and feeling the anxiety drop out of my body. I imagine spending time in there with my family, safe and secure, becoming my best version of myself.’ Another, when questioned about what they might do in their bunker, responded, ‘Well, you could do anything, you could learn how to meditate, you could learn how to levitate, you could walk learn how to walk through walls. When you get rid of all the distractions and crap around us keeping us from doing these things, who knows what you can accomplish?’ Such suggestions undermine the assertion that ‘the desire to remain corporeally unchanged or unaffected emerges as a foundation for survivalism’ (Rahm, 2013: 3). Preppers desire what they dread precely due to the hope that change offers.

The bunker is imagined by some as a chrysalis for transformation into a model self, where preparations lead to a perfectly routine existence, where individuals can emerge as a superior version of themselves (Nietzsche, 1978 [1883]). Many of us experienced this fantasy playing out during the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, which for some brought relief from unwanted travel obligations and for others provided a productive period of isolation and privacy. A utopia for some was a disaster for others, who were without the resources to hunker down were left jobless, sick, and dead. The bunker fantasy is based on a return to phenomenology, where materials, bodies and matter take precedence over connection and speed. The rational, orderly, planned space of the bunker is the antithesis of pointless acceleration and accumulation. These narratives contrast media driven and research-based-on-representation accounts of prepping and bunker building as a gloomy, dystopian practice. Prepping is ultimately hopeful, if selfish.

Subterranean space has always been populated by dark threats and utopian promises (Macfarlane, 2019). In Tarde’s (1905) utopian treatise The Underground Man, a ‘fortunate disaster’ pushes humankind to burrow, where people not only survive but thrive, after being forced to create a more sustainable and egalitarian society in the confined spaces they inhabit. The imaginations of present-day preppers in many ways echo this century-old utopian dream in their reconceptualization of underground space as a laboratory to build a better body and mind.

Despite the dreadful allure of ‘bunker time’, one bunker resident explained to me that that ‘no one wants to go into the bunker as much as they want to come out of the bunker.’ As such, the bunker is a transportation architecture, but rather than transport bodies and material through space, it transports them through time.

The bunker facilitates not only time travel but the slowing of time, making it not only an architectural form but a way of ordering material in relation to time. There is an anticipated temporality in each case, an expectation of how long shelter must be sought before the danger has passed and re-emergence is possible. Though the temporal boundaries of the crisis may be unknown at the outset (as with COVID-19) the temporality of the space is always pre-calculated. The period assigned, be it a week, month, a year or five, is both speculative and crucial. A crisis chronopolitics arises when the expected time through which the bunker is built to transport bodies is interrupted and the contents emerge too soon or too late (see Fish and Garrett, 2019).

As Rosalind Williams (2008: 21) has written, ‘the subterranean environment is a technological one – but it is also a mental landscape, a social terrain, and an ideological map.’ These developments, then, are a spatial manifestation of a social consciousness saturated with dread about tenuous futurities. The privatisation of subterranean hardened architecture constitutes a reconfiguration of volumetric territory based on prediction and speculation, a worldview committed to adaptation rather than mitigation, a move from geopolitics towards chronopolitics (Virilio, 1999).

Our present crisis is not one of space but time. The bunker is defined not by its form but by its function, which is resurrection. Making the trip though the subterranean ark possible is a community of people with complementary skills required for the crossing. What is meant to emerge from the private chrysalis is a community who hold a body of knowledge and the materials to rebuild (Dartnell, 2015). In this way, the personal/family backyard shelters of the first doom boom contrast modern bunkers, just as survivalists of the past are a markedly different community than the preppers of today. Contemporary bunker communities are a ‘…a diverse kinship of chthonic earthly forces that travel richly in space and time’ (Haraway, 2016: 121).

In Larry Hall’s imagination of the crossing, psychological and social factors play a crucial role, since ‘one can imagine a future environment that adequately provides the material basis for human life but is psychologically and socially intolerable’ (Williams, 2008: 2). The temporality of the bunker is embodied in the material substance of the space, the hardened architecture and stores and stocks, but is equally about cultivating a socially copacetic environment in the bunker . Hall explained that,

In sociology there’s a structure defined as an extended family – it’s a group of more than 20 people but less than 120 that share close proximity and a common goal. With fewer than 20, you don’t get your societal needs met and you really don’t want those people to be family members, because you also need to interact with strangers in order to have your societal needs met. And if you got over 120 cliques started to form. This is a 54,000 ft.2 facility with a common goal of survival. In terms of sociability and productivity we got the optimal setup. Even though we can support 75 in this facility the current owners are only 55 or 56 people, which is great.

There would also be a system of rotating jobs for the five years, both so that people would be occupied (‘People on vacation constantly get destructive tendencies’, he said) and so that they would individually learn the different critical operations in the bunker. This was a lesson learned from the ASU’s Biosphere 2 project, where scientists were locked into a closed ecosystem for two years as an experiment in self-contained sustainability. During that experiment, Larry explained ‘they almost got into a serious situation because somebody got sick and had to be taken out and no one else knew how to run the pumps’ (see Alling et al., 1993). Thus, it was crucial that everyone share information about jobs and roles. In fact, Larry explained, they had hired a consultant who had worked on Biosphere 2 to assist in the planning of the Survival Condo:

She went over everything in meticulous detail, from the frequency to the textures to the colours on the walls. All the LED lights in the bunker are set to 3000° Kelvin to prevent depression. People come in here and they want to know why people need all this ‘luxury’ – the cinema, rock climbing wall, table tennis, video games. shooting range, sauna, library and everything, but what they don’t get is that this isn’t about luxury, this stuff is key to survival.

If you don’t have all this built in, your brain keeps subconscious score of abnormal things and you start to get varying degrees of depression or cabin fever. Whether you’re woodworking or just taking the dog for a walk, it’s crucial to people feeling that living in relatively normal life, even if the world is burning outside. You want good quality food and water and for everyone to feel safe and to feel they’re working together towards a common purpose. This thing’s got to function like a miniature cruise ship.

'Doomsday' bunkers pose fascinating and important questions about materiality, as sites of geological-geopolitics and harbour a unique spatiality, in that they are a volumetric extension of atomised life in late capitalism – a kind of uber-gated community – but the primary attribute of these bunkers is in the way they temporalize space. Beck (2011: 82) rightly notes that ‘the bunker promises security and control in the form of refuge… both womb- and tomb-like.’ A bunker built with no resurrection temporality is a sepulchre rather than a bunker, and resurrection is crucial to capitalism, since as Bauman explains, capitalism prefigures the,

…the certainty that tomorrow can’t be, shouldn’t be, won’t be like it is today [and so called for] a daily rehearsal of disappearance, vanishing, effacement and dying; and so, obliquely, a rehearsal of the non-finality of death, of recurrent resurrections and perpetual reincarnations (Bauman, 2006: 13).

Over 60 m below the surface of the earth, we looked over racks filled with 25-year shelf life food stored in racks on the Grocery Store level in the silo, a convincing simulacrum of a supermarket, complete with shopping baskets, cold cases, an espresso machine behind the counter, and a middle-class-America-aesthetic (Fig. 5 ). Hall told me that,

We needed low black ceilings, beige walls, a tile floor, and nicely presented cases, because if people are locked in this building and they have to come down here and rifle through cardboard boxes to get their food, you will have depressed people everywhere.

Fig. 5.

The ‘General Store’ in the Survival Condo (image by author).

He went on to explain that although long-term food storage was paid as part of the dues, it could not be used in a non-emergency situation. ‘If we’re planning for five years and then find half the cans have walked out of here when we need them, we’re going to have strained relationships.’ It was also necessary to implement a rule that no one could take more than three days-worth of groceries, because shopping is a social event. He elaborated that ‘since everything in here is already paid for, you need to encourage people to come down here to smell bread and make a coffee and to chat or barter supplies and services.’

We visited one of the completed 1800-square-foot condos, which felt like a clean, predictable hotel room. I looked out of one of the windows and was shocked to see that it was night outside. I guessed we must have been underground for more than a few hours at this point.

I had completely forgotten we were underground. Larry picked up a remote control and flicked on a video feed being piped into the ‘window’: a vertically-installed LED screen. Oak leaves suddenly shuddered in the foreground just in front of our cars, parked outside the blast door. In the distance, the camouflaged sentry posted at the chain link fence was standing in the same place as when we arrived.

‘The screens can be loaded up with material or have a live feed piped in, but most people prefer to know what time of day it is than to see a beach in San Francisco or whatever,’ Larry explained. ‘The thing the consultant drilled in again and again was that my job as the developer was to make this place is as normal as possible. All that security infrastructure, you want people to know how it works and how to fix it, but we don’t want to be reminded all the time that you are basically living in a spaceship or a submarine.’

As in those spatial transport systems, simply building the bunker, and knowing how to operate it, does not guarantee a safe crossing, you must have a destination plotted. The point of emergence here is a time in the future, and the hope is that the resurrection destination is an inhabitable earth. Arrival is not guaranteed, but the bunkers are built and the bet taken, because as Mark O’Connell (2017: 36) writes – in relation to transhumanist cryogenics – it’s a secular variation on Pascal’s Wager: ‘…although you may not be guaranteed resurrection if you sign up, you’re seriously diminishing your chances if you don’t.’ If the point of the bunker is to emerge under the agency of your anticipatory temporality, these bunkers reflect current socio/political anxieties about future uncertainty, and ‘by resurrecting the dead we solve the problem of alienation from time’ (Paglen, 2018: np).

Should our species survive in the spaces dread wrought, spaces like Survival Condo, future archaeologists might read the subterranean sanctuaries in a sanguine light, ‘where the advanced model [of humanity] realises itself’ (Delillo, 2016: 258). This possibility is what many preppers put their belief in. The bunker is, for them, both a controlled laboratory in which to build better selves, reasserting lost agency, and a chrysalis from which to be reborn after a necessary ‘reset’ of a messy, complicated, and fragile world.

The bunkers being built by preppers might reflect atomisation but they are not a terminal architecture, they are a social prism through which to understand dialectical hope in dread. As sociologist Richard J. Mitchell writes in his study of late 20th-century survivalists, they were ‘not just a consequence, a dependent variable, a result of the conditions of contemporary social life, but… an indicator, a lens for perceiving and understanding those conditions’ (Mitchell, 2002: 146). Equally, by expanding optics on the materiality of the bunker to give serious consideration to the social forces behind contemporary underground construction, and the completely rational retreat into them during the COVID-19 pandemic, it becomes clear that the preppers are not social anomalies, but gatekeepers to understanding the contemporary human condition (Garrett, 2020). Spaces like the Survival Condo seem improbable, if not impossible, and yet as Kierkegaard writes, dread spawns from the possible and ‘possibility means I can’ (Dru, 1938, p. 44). It’s the choice to act that matters; in action hope can spawn from dread, as Larry Hall suggested at the end of our tour when he told me:

This was not a space of hope. The defensive capability of this structure only existed to the extent needed to protect a weapon, a missile – this bunker was a weapon system. So, we converted a weapon of mass destruction into the complete opposite…

Ethnographic research makes evident that the subterranean state geopolitics of the past, whilst still in play, have become interleaved into defensive architecture through new works of ‘culture crafting’ (Mitchell, 2002: 9) that reflect our collective neuroses in the midst of an Anthropocene that is ‘neither sacred nor secular; this earthly worlding is thoroughly terran, muddled, and mortal – and at stake now’ (Haraway, 2016: 152). The world we knew has collapsed and the world of the future, failing a flight from earth, may well be underground. Coming to know the players in subterannea, including the preppers constructing spaceships for a ride through time, will (re)frame the geo as the bunker shifts out of it's role as a defensive redoubt for temporary or speculative war and becomes and space of forceful and active epistemology of private chthonic cronopolitics in an age of dread.

Acknowledgement

The research was funded by a three-year Sydney Fellowship at the University of Sydney. The IRMA Project ID is 192231.

References

- Adey Peter. Securing the volume/volumen: comments on Stuart Elden’s Plenary paper ‘Secure the volume’. Polit. Geogr. 2013;34:52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Adey Peter, Anderson Ben. Anticipating emergencies: technologies of preparedness and the matter of security. Security Dialog. 2012;43(2):99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alling Abigail, Nelson Mark, Silverstone Sally. Synergetic Press; New Mexico: 1993. Life Under Glass: The Inside Story of Biosphere 2. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson Rowland, Blandy Sarah. Manchester University Press; Manchester: 2017. Domestic Fortress: Fear and the New Home Front. [Google Scholar]

- Barker Kezia. How to survive the end of the future: Preppers, pathology, and the everyday crisis of insecurity. Trans. Inst. Brit. Geogr. 2019;(Online First):1–14. doi: 10.1111/tran.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Zygmunt. Survival as a social construct. Theory, Cult. Soc. 1992;9:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Zygmunt. Polity Press; London: 2006. Liquid Fear. [Google Scholar]

- Beck John. Concrete ambivalence: Inside the bunker complex. Cult. Polit. 2011;7:79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop Ryan. Project ‘Transparent Earth’ and the autoscopy of aerial targeting: the visual geopolitics of the underground. Theory, Cult. Soc. 2011;28(7–8):270–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke Joanna. Counterpoint Press; Berkeley: 2006. Fear: A Cultural History. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge Gavin. Territory, now in 3D! Polit. Geogr. 2013;34:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Norah, Sinclair Gary, Browne Sarah. Preparing for a world without markets: legitimising strategies of preppers. J. Market. Manage. 2019;35(9–10):798–817. [Google Scholar]

- China, Miéville, 2014. ‘Dread: the Surplus Value of Fear’. In: Zelfde, Juha Van ’t. 2014. Dread: the Dizziness of Freedom. Amsterdam: Valiz.

- Cioran, Emil, 1992 (1934). On the Heights of Despair, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Chambliss Wayne. In: Voluminous States: Sovereignty, Materiality, and the Territorial Imagination. Billé Franck., editor. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 2020. Spoofing: The Geophysics of Not Being Governed. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Dartnell Lewis. Vintage; London: 2015. The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Our World After an Apocalypse. [Google Scholar]

- De Cauter, Lieven, 2004. The Capsular Civilization: On the City in the Age of Fear, Amsterdam: NAi.

- DeLillio Don. Picador; London: 2016. Zero K. [Google Scholar]

- Dru Alexander. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1938. The Journals of Kierkegaard. [Google Scholar]

- Elden Stuart. Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Polit. Geogr. 2013;34:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer, Alan., 2013. The Preppers Next Door. New York Times, 26 Jan (accessed 21 November 2019).

- Fish Adam, Garrett Bradley. Resurrection from bunkers and data centres. Cult. Mach. 2019;18:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Foster Dawn. Palgrave; London: 2014. Hoarders, Doomsday Preppers, and the Culture of Apocalypse. [Google Scholar]

- Freud Sigmund. Dodo Collections; London: 1920. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett Bradley. Bunker: Building for the End Times. Scribner; New York, NY: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett Bradley, Klinke Ian. Opening the bunker: function, materiality, temporality. Environ. Plann. A: Econ. Space. 2018;29:421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett Bradley, Melo Zurita Maria de Lourdes, Iveson Kurt. Boring cities: The privatisation of subterranea. City: Anal. Urban Trends, Cult., Theory, Policy, Action. 2020;(Online First) [Google Scholar]

- Graham Stephen. Verso; London: 2016. Vertical: The City from Satellites to Tunnels. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Stephen, Hewitt Lucy. Getting off the ground: On the politics of urban verticality. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012;37(1):72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hall John R. Polity; London: 2009. Apocalypse: From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm Mark. Northeastern University Press; New England: 1997. Apocalypse in Oklahoma: Waco and Ruby Ridge Revenged. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway Donna. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston Chad. In: Responses to Disasters and Climate Change. Companion Michele, Chaiken Miriam., editors. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2016. ‘Prepper’ as resilient citizen: understanding vulnerability and fostering resilience; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kabel Allison, Chmidling Catherine. Disaster prepper: health, identity, and American Survivalist Culture. Hum. Organ. 2014;73(3):258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly Casey Ryan. The man-pocalypse: doomsday preppers and the rituals of apocalyptic manhood. Text Perform. Quart. 2016;36(2–3):95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kierkegaard, Søren, 1968. [1844]. The Concept of Dread New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Kindynis Theo. Subterranean (In)Securities: Inequality, crime, deviance and social control underground. City: Anal. Urban Trends, Cult., Theory, Policy, Action. 2020 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Klein Naomi. Allen Lane; New York: 2017. No is Not Enough. [Google Scholar]

- Klinke Ian. Cryptic Concrete: a Subterranean Journey Into Cold War. Wiley-Blackwell; London: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy Philip. Springer; New York: 1996. Millennium Rage: Survivalists, White Supremacists, and the Doomsday Prophecy. [Google Scholar]

- Lapham Lewis. Harper’s Quarterly; Fear: 2017. Petrified Forest; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corbusier, 1986 (1931). Towards a New Architecture. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications.

- Macfarlane Robert. W. W. Norton & Company; London: 2019. Underland: A Journey Into Deep Time. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, Daniele, 2009. Bunkers for all. Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, July 3. Available at: https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/prepared-for-anything_bunkers-for-all/995134 (accessed 17 October 2017).

- Marvin, Simon, Hodson, 2016. Cabin ecologies: the technoscience of integrated urban infrastructure. In: Evans, J., Karvonen, A. & Raven, A. (Eds.), The Experimental City, Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 88-106.

- Marvin Simon, Rutherford Jonathan. Controlled environments: An urban research agenda on microclimatic enclosure. Urban Stud. 2018;55(6):1143–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Mills Michael. University of Kent; UK: 2017. Witness to the American Apocalypse? A Study of 21st-Century Doomsday Prepping. (unpublished PhD thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Mills Michael. Preparing for the unknown unknowns: ‘Doomsday” prepping and disaster risk anxiety in the United States. J. Risk Res. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Mills Michael. Obamageddon: fear, the right, and the rise of ‘Doomsday’ prepping in Obama’s America. J. Am. Stud. 2019:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Minton Anna. Penguin; London: 2012. Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Richard. Chicago University Press; Chicago: 2002. Dancing at Armageddon: Survivalism and Chaos in Modern Times. [Google Scholar]

- Monteyne David. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 2011. Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defence in the Cold War. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Fredrich, 1978 [1883]. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. London: Penguin.

- O’Connell Mark. Doubleday; New York: 2017. To be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death. [Google Scholar]

- Paglen, Trevor, 2018. Fedorov’s Geographies of Time. E-flux #88.

- Peterson Richard G. Preparing for apocalypse: survivalist strategies. Free Inquiry Creative Sociol. 1984;12(1):44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pinder David. Routledge; New York: 2006. Visions of the City: Utopianism, Power and Politics in Twentieth Century Urbanism. [Google Scholar]

- Rahm Lina. Who will survive? On bodies and boundaries after the apocalypse. Gender Forum: Internet J. Gender Stud. 2013;(45) [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro Matan, David-Bird Nurit. Routinergency: Domestic securitization in contemporary Israel. Environ. Plann. D: Soc. Space. 2017;35(4):637–655. [Google Scholar]

- Siffre Michael. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1964. Beyond Time. [Google Scholar]

- Situationist International . In: Situationist International Anthology. Knabb Ken., editor. Bureau of Public Secrets; Berkeley: 2007. The Geopolitics of Hibernation; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Stec, Carly, 2016. The Doom Boom: Inside the Survival Industry’s Explosive Growth. HubSpot. Available at: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/survival-industry-growth (accessed 9th November 2018).

- Szasz Andrew. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 2007. Shopping Our Way to Safety How We Changed from Protecting the Environment to Protecting Ourselves. [Google Scholar]

- Tarde G. Dover Publishing; Mineola: 1905. The Underground Man. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker Eugene. Notes on extinction and existence. Configurations. 2012;20(1–2):137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbilt Tom. Princeton Architectural Press; New York: 2002. Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America. [Google Scholar]

- Virilio Paul. Princeton Architectural Press; New Jersey: 1994. Bunker Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Virilio Paul. Semiotext(e)/Foreign Agents; Los Angeles: 1999. Politics of the Very Worst. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, O., 2012. Billionaires’ basements: the luxury bunkers making holes in London streets, Guardian Cities. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/nov/09/billionaires-basements-london-houses-architecture (accessed 17 October 2018).

- Williams Rosalind. MIT Press; Cambridge: 2008. Notes on the Underground. [Google Scholar]

- Zelfde, Juha Van ’t, 2014. Dread: the Dizziness of Freedom. Amsterdam: Valiz.