Dear editor,

We read with great interest the recent manuscript published by Zhou et al. describing the clinical characteristics of myocardial injury in severe and very Severe patients with Coronavirus 2019 disease.1 Also other recent investigations have reported a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and a direct association between the severity of COVID-19 infection.2 However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous meta-analyses have globally estimated the risk of death in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 infection. We therefore perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the risk of death in COVID-19 infection patients with and without HT.

The analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Supplementary file 1).3 An electronic search, based on Medline (Pubmed interface), Scopus and Web of Science, was performed to locate articles any time up to March 23, 2020 comparing the survival between HT and no-HT patients with COVID-19 infection. Three reviewers (G.R., M.Z. and L.R.) independently screened and selected the studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following MeSH terms were used for the search: “Arterial hypertension” AND “ coronavirus 2019 mortality” OR “COVID-19 mortality” OR “Coronavirus 2019 survivors” OR “ COVID-19 survivors” and “Coronavirus 2019” OR “COVID-19” AND “mortality”. Case reports, review articles, abstracts, editorials/letters, and case series with less than 10 participants were excluded. Extracted data included: number of patients enrolled, mean age, male gender, prevalence of HT, diabetes mellitus and other cardiac comorbidities.

The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) investigations comparing the survival between HT and no-HT (control group) COVID-19 patients; (2) patients must have a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and (3) articles published in English language. Conversely, exclusion criteria were studies without a comparison arm (survivors versus not survivors) in COVID-19 patients and absence of data regarding the prevalence of HT.

The study selection and quality of the included studies was independently performed by two reviewers (G.R. and M.Z.). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third independent reviewer (L.R.). Specifically, quality assessment was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS).4 In this regard, investigations were classified as having low (< 5 stars), moderate (5–7 stars) and high quality (> 7 stars). Publication bias was evaluated according to the funnel plot asymmetry.5

The primary outcome was the overall prevalence of HT obtained by the reviewed cohorts of patients with COVID-19. The secondary outcome was the risk of death in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 infection.

Continues variables were expressed as mean while categorical variables, were presented as proportions. Data were pooled using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects models with odds ratio (OR) as the effect measure with the related 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical heterogeneity between groups was measured using the Higgins I2 statistic. Specifically, a I2 = 0 indicated no heterogeneity while we considered low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity based on the values of I2 as <25%, 25–75% and above 75%, respectively. All analyses were carried out using Review Manager 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England).

A total of 213 articles were retrieved after excluding duplicates. After the initial screening, 197 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 16 articles to assess for eligibility. After a comprehensive and careful evaluation of the full-text articles, 13 articles including editorial/letter, reviews, case reports, and investigations not in English language were excluded. Finally, 3 articles were included into the analysis6, 7, 8 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of selected studies for the meta-analysis according to the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Among 419 patients (259 males (61.8%), mean age 55.6 years), HT resulted the most frequent CV comorbidities (24.3%), followed by diabetes mellitus (15.2%) and cardiac disease (6.2%). However, for the last comorbidity, minor variations were used in the definitions in the studies reviewed. According to the NOS, two studies resulted of high-quality and one of moderate quality (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the patients enrolled.

| Authors | Number of patients | Mean age (years) | Males N, (%) | HT N, (%) | Diabetes N, (%) | CVD N, (%) | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al.6 | 201 | 51 | 128 (63.7) | 39 (19.4) | 22 (10.9) | 8 (4.0) a | High quality |

| Yuan et al.7 | 27 | 60 | 12 (44.4) | 5 (18.5) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (11.1) b | Moderate quality |

| Zhou et al.8 | 191 | 56 | 119 (62.3) | 58 (30.3) | 36 (18.8) | 15 (7.8) c | High quality |

Defined as cardiovascular disease

Defined ad cardiac disease

Defined as Coronary artery disease.

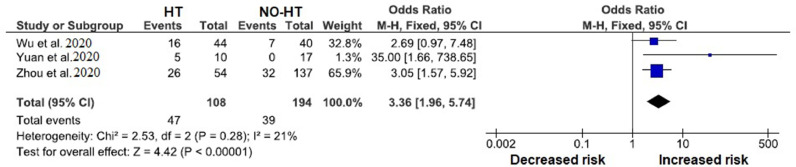

As showed Fig. 2 , hypertensive patients with COVID-19 infections had a significant higher mortality risk compared with normotensive patients (OR 3.36, 95% CI 1.96- 5.74, p <0.0001, I2 = 21%).

Fig. 2.

Forrest plots of primary outcome: all‐cause mortality among COVID-19 patients with and without arterial hypertension. HT: Arterial hypertension

Our brief meta-analysis demonstrated that patients with COVID-19 infection and HT have a significant high mortality risk. The association between the presence of HT and a poor outcome in COVID-19 patients was partially demonstrated in single analysis, but never into a meta-analysis.6 , 9 Doubtless, considering that the data used for our investigation derive only from Chinese cohorts, other analysis based on different cohorts should be performed to validate our observations because the prevalence of HT, as well as for others CV risk, can have different results across different regions and races. However, despite our findings should be considered as prelaminar results, we believe that remains fundamental to preliminary identify the “phenotype” of those patients which could be at higher risk of death during the COVID-19 infection.10 The preliminary knowledge of those comorbidities incrementing the risk of death of COVID-19 patients results fundamental both for outpatients and hospitalized subjects to maintain a high degree of surveillance until the resolution of the disease, since COVID-19 infection could rapidly turn into an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) up to a multiorgan failure (MOF). In our analysis we included only those studies which stratified the cohorts into survivors and not survivors because the mortality represents an undeniable result. In fact, many other investigations used more “uncertain” outcome as the severity of the disease which was often defined using different criteria.

Our study has several limitations related to the observational nature of the studied reviewed with all inherited biases. Secondly, very few investigations on the COVID-19 infection have stratified the cohort into survivors and non survivors, limiting the number of investigations included into the meta-analysis. Thirdly, in the analysis, the degree of increased risk of mortality in HT patients was largely due to two studies having 65.9& and 32.8% of weight. Moreover, the high heterogeneity observed, which depends from the participants’ inclusion criteria as well as by the studies design, may have resulted in relatively weak conclusions.

In conclusion, HT is the most common CV comorbidity which seems to significantly increase the mortality risk in COVID-19 patients. Further studies are needed to explain the underline pathophysiological mechanisms linking HT and COVID-19 infection.

Declaration of Competing of Interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhou B., She J., Wang Y., Ma X. The clinical characteristics of myocardial injury 1 in severe and very severe patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.021. S0163-4453(20)30149-3Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., Ji R., Wang H., Wang Y., Zhou Y. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. S1201-9712(20)30136-3Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. Group Altman DG PRISMA. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses, 2012. Available from: http://www.ohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp.

- 5.Sterne J.A., Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X., Du C., Zhang Y., Song J., Wang S., Chao Y., Yang Z., Xu J., Zhou X., Chen D., Xiong W., Xu L., Zhou F., Jiang J., Bai C., Zheng J., Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan M., Yin W., Tao Z., Tan W., Hu Y. Association of radiologic findings with mortality of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss P., Murdoch D.R. Clinical Course and Mortality Risk of Severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4. [ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.