Dear editors,

Previous reports revealed that the emergence of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) had raised global concern.1 Several studies discussing the clinical pictures of COVID-19 and specific antibody responding to SARS-CoV-2 have been published.2, 3, 4 However, the time sequences of clinical manifestations, virus shedding kinetics, contagiousness, and specific antibody reaction, which are essential for understanding pathophysiology and infection control strategy, have less been discussed. Here we present a COVID-19 patient with prolonged viral shedding and detailed time sequence of these parameters mentioned above.

A 50-year-old woman, who suffered from acute-onset fever up to 38.6 °C four hours ago, visited the emergency department of a medical center in Taipei City, Taiwan. She denied of cough or other subjective discomforts, and disclosed that she lived in Wuhan, China and just traveled to Taiwan two days prior to hospital visit. Given the patient's travel history, she was transferred to a negative-pressure isolation room for suspecting COVID-19.

Chest radiography was normal. Hemogram revealed only mild thrombocytopenia (143 K/μL), while other blood tests were within normal limits. Sputum and throat swab specimens yielded positive results for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Fever subsided rapidly after admission. However, elevated temperature up to 38.2 °C was noted four days later. She did not have obvious respiratory symptoms and remained good spirit. All blood tests, except mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (1.47 mg/dL) and mild thrombocytopenia, were normal. A once-daily low-grade fever persisted until ninth day after symptom onset. The CRP level reached to the peak on the tenth day after symptom onset and then normalized gradually.

Clinical specimens for SARS-CoV-2 testing were obtained in accordance with guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.5 During hospitalization, sputum and throat swab specimens were collected for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and virus culture every other day. Throat wash by gargling using 10 mL normal saline were collected when sputum specimens were not available.6 Stool was collected for RT-PCR on the third, 14th and 20th day after symptom onset, and plasma was also sent within the first four days of hospitalization. Serum was sent for SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection every or every other day within the first 21 days of hospitalization.

Plasmid DNA containing the SARS-CoV-2 target sequences, including the envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) genes, was used to construct the standard curve to estimate the SARS-CoV-2 viral load by real-time RT-PCR. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 isolation was performed via Vero E6 and LLC-MK2 cell cultures. The full-length viral sequence was determined using SARS-CoV-2 amplified from the sputum specimen collected on the ninth day after symptom onset, and was submitted to the GISAID (accession number is EPI_ISL_408,489). Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 viral N proteins was determined by western blotting using infected cell lysates.

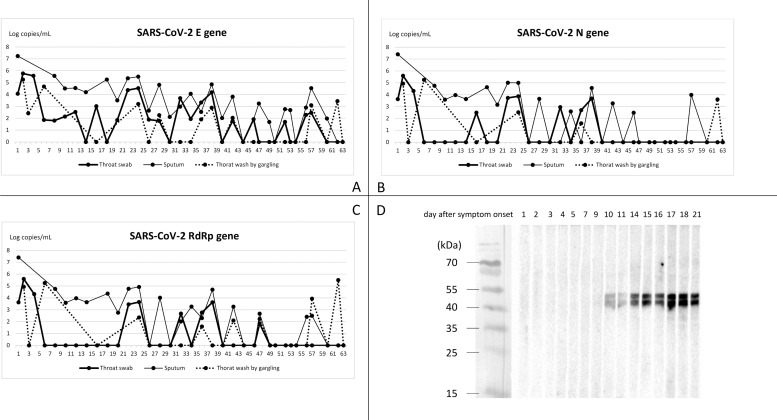

The sequential changes of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in throat swab, sputum, and gargling water are presented in Figure. A drop of three logs of viral loads was observed among all specimens within one week after admission. However, SARS-CoV-2 persisted to be detectable till 63th day after symptom onset. Among respiratory specimens from different sites, specimen from sputum showed superior sensitivity to samples from throat swab and gargling wash. Initially, specimen from gargling wash showed considerable results compared with specimens from sputum or throat swab. Nevertheless, RT-PCR examinations from sputum still outweighed samples from gargling and throat swab after fever subsided. Among three target genes of the RT-PCR examinations, E gene of SARS-CoV-2 showed superior sensitivity to N and RdRp gene after clinical symptoms resolved. The stool specimen collected on the third day after symptom onset yielded positive results, but turned negative in the following specimens. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 could not be detected in the plasma samples while the SARS-CoV-2 titers in the respiratory specimen remained high.

SARS-CoV-2 could be isolated from cell cultures in throat swab collected upon admission, and all sputum specimens collected within 18 days after symptoms onset. RT-PCR continued to detect virus till the 63th day after symptom onset regardless virus could only be isolated from respiratory specimens collected within the first 18 days. Antibody to SARS-CoV-2 was firstly identified on the tenth day after symptom onset. In the meanwhile, no more fever above 37.5 °C was noted, and CRP began to decline. Recovery of platelet count took place two days earlier than the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 antibody.

This case demonstrated that the virus shedding might continue even after clinical resolution and seroconversion. In addition, although SARS-CoV-2 virus could not be isolated after the 18th day of symptom onset, the positive RT-PCR results continued for more than 60 days. Because of the long interval between these two time points, it might be reasonable to infer that a small amount of viable virus, yet could not be detected by virus culture, remained present after the 18th day of disease course and last for more days. This implies the contagious period of COVID-19 might last more than one week after “clinical recovery”. Many of COVID-19 patients in Taiwan also had similar findings (unpublished data). Such prolonged virus shedding was also observed among asymptomatic pediatric patients in fecal specimen.7 However, this needs more studies to clarify since it would be a major issue in realizing and controlling the COVID-19 epidemics.

Serial RT-PCR results in our case highlighted the importance of the clinical specimens sampled from lower respiratory tract for detecting SARS-CoV-2 virus,8 which is different from the report from Zou L, et al.9 Additionally, our case demonstrated that throat wash by gargling could be an alternative method for COVID-19 diagnosis, since specimen from lower respiratory tract was barely available at the early stage of infection. Nevertheless, when the patient became afebrile, sputum still outweighed specimens from throat swab or gargling wash.

Our case highlighted the prolonged virus shedding course of COVID-19 even after the clinical symptoms resolved and seroconversion developed. It implies the possibility of a prolonged contagious period and should be investigated further to better control the epidemics. Our study also demonstrated viral detection from throat gargling sample could be an alternative diagnostic method for patients without sputum. Fig. 1

Fig. 1.

Profile of viral load and antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 in the case patient. (A)(B)(C) Sequential changes of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the throat swab, sputum, and throat wash by gargling. The SARS-CoV-2 viral load was determined using the protocol provided by the WHO (https://virologie-ccm.charite.de/en). Plasmids containing partial E, N, and RdRp fragments were used respectively as the standards to calculate the amount of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the specimens. (D) Antibody responses of the present case. Antibody responses of the present case to viral proteins extracted from SARS-CoV-2 infected Vero-E6 cells were determined by the western blot.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None to declare.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

References

- 1.Tang J.W., Tambyah P.A., Hui D.S.C. Emergence of a novel coronavirus causing respiratory illness from Wuhan, China. J Infect. 2020;80(3):350–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao D.A.T., Gao D.C., Zhang D.S. Profile of specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2: the first report. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.012. pii: S0163-4453(20)30138-9[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W., Cao Q., Qin L., Wang X., Cheng Z., Pan A. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016. pii: S0163-4453(20)30099-2[Epub ahead of print]<. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from persons under investigation (PUIs) for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.htmlAccessed 7 Mar 2020.

- 6.Wang W.K., Chen S.Y., Liu I.J., Chen Y.C., Chen H.L., Yang C.F. Detection of SARS-associated coronavirus in throat wash and saliva in early diagnosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1213–1219. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.031113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [Epub ahead of print]<. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]