The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the U.S. health care system. To preserve resources, including personal protective equipment and hospital beds to care for COVID-19 patients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended deferral of elective cardiac procedures (1), including coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary artery disease.

Timely reperfusion by means of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the standard of care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients (2). The Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions and American College of Cardiology continue to recommend PPCI as the standard treatment of STEMI patients during the current pandemic (3). However, anecdotal reports suggest a decline in PPCI volumes in the United States and around the world (4).

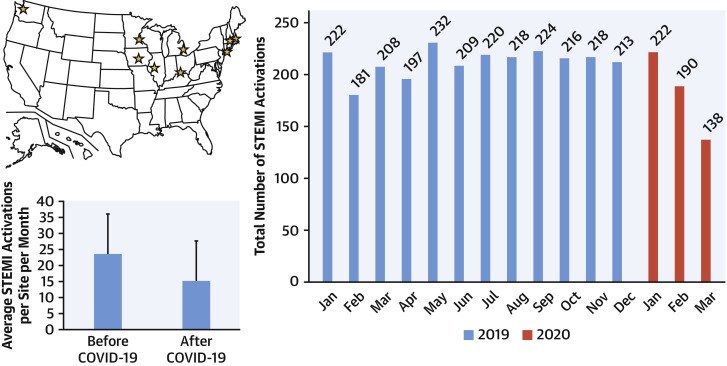

To determine whether a decrease in PPCI is occurring in the United States in the COVID-19 era, we analyzed and quantified STEMI activations for 9 high-volume (>100 PPCIs/year) cardiac catheterization laboratories in the United States from January 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020. Participating hospital systems included: 1) Minneapolis Heart Institute, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 2) Beaumont Hospital Royal Oak, Royal Oak, Michigan; 3) The Christ Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio; 4) Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; 5) UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts; 6) Iowa Heart, Des Moines, Iowa; 7) Northwell Health Hospital, Manhasset, New York; 8) Prairie Cardiovascular, Springfield, Illinois; and 9) Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, Washington.

In this study, March 1, 2020, was identified as the beginning of the “after COVID-19” (AC) period when U.S. social life and medical operations were significantly affected (March 1, 2020, was also the day that New York City, the epicenter of U.S. COVID-19 cases, reported its first COVID-19 case). Social distancing was recommended by the federal government on March 15, 2020. The “before COVID-19” (BC) period comprised the 14 months leading up to the epidemic in the United States (January 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020). We now compared the BC and AC monthly total and average number of STEMI activations for each hospital.

A mixed model with random intercepts corrected for time as a continuous variable was used to estimate the percent change in STEMI activations in the BC versus AC period. The model estimate showed a decrease in STEMI activations of 38% (95% confidence interval: 26% to 49%; p < 0.001). All sites combined reported >180 STEMI activations every month (mean 23.6 activations/month) in the BC period. In contrast, all sites combined reported only 138 activations (mean 15.3 activations/month) in the AC period (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

STEMI Activations During the COVID-19 Pandemic

(Top left) Map of the United States showing the 9 high-volume ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) centers participating in this registry (yellow stars). (Lower left) Bar chart displaying average number of STEMI activations per site per month before and after the COVID-19 pandemic affected the U.S. health care system. (Right panel) Bar chart displaying total number of STEMI activations per month (blue: 2019; red: 2020).

Our preliminary analysis during the early phase of the COVID pandemic shows an estimated 38% reduction in U.S. cardiac catheterization laboratory STEMI activations, similar to the 40% reduction noticed in Spain (4). A priori, given the potential heightened environmental and psychosocial stressors and a higher case of STEMI induced by viral illness (e.g., similar to influenza) (5) or mimickers such as COVID-19 myopericarditis, an increase in STEMI activations would have been expected. Potential etiologies for the decrease in STEMI PPCI activations include avoidance of medical care due to social distancing or concerns of contracting COVID-19 in the hospital, STEMI misdiagnosis, and increased use of pharmacological reperfusion due to COVID-19. As the pandemic continues, we plan to continue to follow this early signal and investigate its causes. It is particularly crucial to understand if patient-based anxiety is decreasing presentation of STEMI patients to the U.S. hospital system.

Footnotes

Please note: The regional STEMI program at Abbott Northwestern Hospital is supported by the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation and Allina Health. All authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACCauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhealthcare-facilities%2Fguidance-hcf.html Available at:

- 2.O'Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welt FGP, Shah P.B., Aronow H.D. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Leor O., Cid-Álvarez B., Ojeda S. Impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 sobre la actividad asistencial en cardiología ntervencionista en España. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020 Feb 4 [E-pub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong J.C., Schwartz K.L., Campitelli M.A. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:345–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]