Abstract

Objective

The current study compared the amplitude of transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) and thresholds of pure-tone audiometry between asymptomatic COVID-19 PCR-positive cases and normal non-infected subjects.

Methods

Twenty cases who were confirmed positive for COVID-19 and had none of the known symptoms for this viral infection formed the test group. Their age ranged between 20 and 50 years to avoid any age-related hearing affection. Patients who had definite symptoms of COVID-19 infection as well as those who had a history of hearing loss or a history of any known cause of hearing loss were excluded from the examined sample. TEOAEs amplitude was measured for all participants.

Results

The high frequency pure-tone thresholds as well as the TEOAE amplitudes were significantly worse in the test group.

Conclusions

COVID-19 infection could have deleterious effects on cochlear hair cell functions despite being asymptomatic. The mechanism of these effects requires further research.

Keywords: COVID-19, Corona virus, Hearing loss, Cochlear function

1. Introduction

An acute respiratory disease, caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, previously known as 2019-nCoV), the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread throughout China and received worldwide attention. On 30 January 2020, World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the COVID-19 epidemic as a public health emergency of international concern. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus. Most people infected with the COVID-19 virus experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without requiring special treatment [1].

COVID-19 infection symptoms may appear 2–14 days after exposure (based on the incubation period of COVID-19 virus). The clinical symptoms of COVID-19 patients include fever, cough, fatigue and a small population of patients had gastrointestinal infection symptoms. The elderly and people with underlying diseases are susceptible to infection and prone to serious outcomes, which may be associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and cytokine storm [1,2]. Currently, there are few specific antiviral strategies, but several potent candidates of antivirals and repurposed drugs are under urgent investigation. There are multiple scenarios COVID-19 patients may follow: Some get serious respiratory distress, some improve with medical treatment, the rest recover with no intervention [2].

Several viral infections can cause hearing loss. Hearing loss induced by these viruses can be congenital or acquired, unilateral or bilateral. Certain viral infections can directly damage inner ear structures, others can induce inflammatory responses which then cause this damage, and still others can increase susceptibility or bacterial or fungal infection, leading to hearing loss. Typically, virus-induced hearing loss is sensorineural, although conductive and mixed hearing losses can be seen following infection with certain viruses. Occasionally, recovery of hearing after these infections can occur spontaneously [[3], [4], [5], [6]].

Typically, viruses cause sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL); however, a viral etiology has been proposed for otosclerosis. Infection with HIV can lead to conductive hearing loss (CHL) through bacterial and fungal infections, which become more frequent following the immunosuppression caused by that virus [7]. Hearing loss caused by viruses can be mild or severe to profound, unilateral or bilateral. Mechanisms involved in the induction of hearing loss by different viruses vary greatly, ranging from direct damage to inner ear structures, including inner ear hair cells and organ of Corti (as seen in some of the classically described causes of viral hearing loss such as measles), to induction of host immune-mediated damage [[4], [5], [6],8].

Asymptomatic infection at time of laboratory confirmation has been reported from many settings [2]; a large proportion of these cases developed some symptoms at a later stage of infection. There are, however, also reports of cases remaining asymptomatic throughout the whole duration of laboratory and clinical monitoring. Viral RNA and infectious virus particles were detected in throat swabs from some COVID-19 patients, but they developed none of the symptoms listed above [1]. Although several viral infections may lead to hearing loss, it's still unknown whether COVID-19 has effects on the auditory system or not. Therefore, this research was designed to address the impact of this novel viral infection on the auditory system.

2. Materials & method

Twenty cases who were confirmed positive for COVID-19 and had none of the known symptoms for this viral infection formed the test group for 2 full weeks. Their age ranged between 20 and 50 years to avoid any age-related hearing affection. Patients who had definite symptoms of COVID-19 infection as well as those who had a history of hearing loss or a history of any known cause of hearing loss were excluded from the examined sample. Twenty subjects who had normal hearing (All subjects had audiometric thresholds at or better than 15 dB HL) with no history of a known cause of hearing loss were used as a control group.

All the following procedures were conducted for both test group (at the 14th day after being confirmed COVID-19 positive but asymptomatic) and control group:

-

1-

Meticulous history taking and otological examination were carried out on all subjects before audiological testing.

-

2-

Basic Audiological evaluation. Audiometric thresholds were measured using a calibrated Amplaid 309 clinical audiometer [9]. Air conduction thresholds were measured for frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz using Telephonics TDH39 earphones. Bone conduction thresholds were obtained for frequencies from 250 to 4000 Hz using a Radio Ear B71 bone vibrator. The audiometric thresholds were measured using the modified Hughson-Westlake method [10].

-

3-

Immittance evaluation. Tympanometry was carried out using an Amplaid 775 middle ear analyzer to rule out middle ear pathology.

-

4-

Transient evoked otoacoustic emissions. Transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAEs) were recorded in all subjects using the Madsen Capella Analyzer. The eliciting stimuli consisted of a non-linear click delivered at about 80 dB peak SPL in the ear canal. The spectrum analyzer was triggered at 4 ms after presentation of the stimuli to avoid acoustic ringing of the input stimuli, and the temporal window was set at 20 ms. A total of 260 averages were recorded. TEOAEs were considered present when the reproducibility and stability was >80%. All testing was carried out in a double-walled, sound treated booth within permissible noise limits [11].

An informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved from the Egyptian Central Unit of Medical Service (ECUMS). EMMS also helped the research team to connect with the study subjects. EMMS secured a totally aseptic environment for this research including subjects and equipments.

3. Results

3.1. Pure-tone audiometry

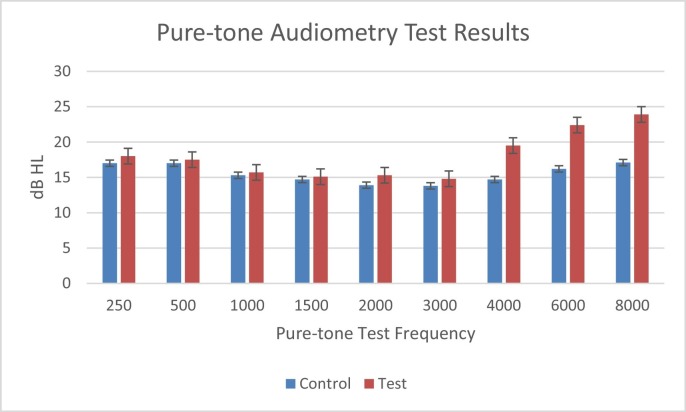

Paired t-test test was used to compare the pure-tone thresholds between the test and the control groups. No significant difference (p > 0.05) was found at all octave and mid-octave frequencies (250, 500, 750, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000), 4000. Significant difference was found (p < 0.05) at 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz between both groups (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Pure-tone audiometric thresholds for both test and control groups.

3.2. TEOAE

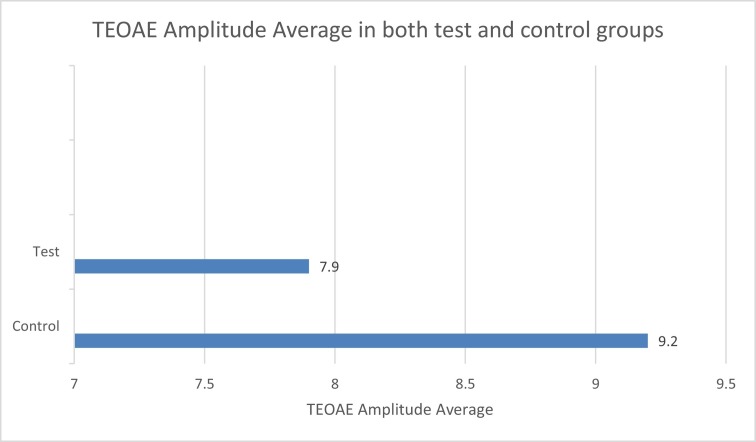

Paired t-test was used to compare the TEOAE amplitude among the control and test groups (p < 0.001). Highly significant difference was found between the control group and the test groups (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

TEOAE amplitude average in both test and control groups.

4. Discussion

The high frequency pure-tone thresholds as well as the TEOAE amplitudes were significantly worse in the test group. The results of the current study showed that COVID-19 infection had deleterious effects on the hair cells in the cochlea. Moreover, the absence of the major symptoms does not guarantee a safe healthy cochlear function. The damage to the outer hair cells was evidenced by the reduced amplitude of the TEOAEs in test group when compared with control group.

Auditory system damage secondary to viral infections is typically intracochlear; however, some viruses can affect the auditory brainstem as well. Mechanisms of injury to the peripheral auditory system can include direct viral damage to the organ of Corti, stria vascularis, or spiral ganglion; damage mediated by the patient's immune system against virally expressed proteins (Cytomegalovirus); and immunocompromise leading to secondary bacterial infection of the ear (Human Immunodeficiency Virus & measles) [3].

Although hearing sensitivity was normal among all participants, TEOAEs could pick up the subtle deterioration in the outer hair cells (OHCs) functions. Additionally, the high frequencies tones were significantly lower in the test group. This deterioration could be attributed to the damaging effects of the viral infection on the outer hair cells but the mechanism is still unknown. The results of the present study also demonstrated that the absence of major symptoms may hide unknown impact on the delicate sensory organs taking the cochlea as an example.

In conclusion, COVID-19 infection could have deleterious effects on cochlear hair cell functions despite being asymptomatic. The mechanism of these effects requires further research.

Acknowledgements

I'm deeply grateful to Egyptian Central Unit of Medical Service (ECUMS). I'm also thankful for the technical support of Sigma incorporation for Audiological Services and the great help and cooperation of Dr. Marwa El Hawary (Alfayoum general hospital) in conducting this research.

References

- 1.Cao Zhong-Si Hong, Tan Yuan-Yang, Chen Shou-Deng, Jin Hong-Jun, Tan Kai-Sen, Wang De-Yun. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak – an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339925460_The_origin_trasmission_and_clinical_therapies_on_coronavirus_disease_2019_COID-19_outbreak_-_an_update_on_the_status available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – seventh update, 25 March 2020. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramovich S., Prasher D.K. Electrocochleography and brain-stem potentials in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112(9):925–928. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780090021002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler S.P. Congenital cytomegalovirus screening. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(12):1105–1106. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200512000-00016. [Aleksic, S. N] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budzilovich G.N., Lieberman A.N. Herpes zoster oticus and facial paralysis (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Clinicopathologic study and review of literature. J Neurol Sci. 1973;20(2):149–159. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Muhaimeed H., Zakzouk S.M. Hearing loss and herpes simplex. J Trop Pediatr. 1997;43(1):20–24. doi: 10.1093/tropej/43.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrasekhar S.S., Connelly P.E., Brahmbhatt S.S., Shah C.S., Kloser P.C., Baredes S. Otologic and audiologic evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)80117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karosi T., Konya J., Petko M., Sziklai I. Histologic otosclerosis is associated with the presence of measles virus in the stapes footplate. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(6):1128–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000169304.72519.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ANSI S3 . American National Standards Institute; New York: 2004. 6-2004 specification for audiometers. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carhart R., Jerger J.F. Preferred method for clinical determination of pure tone thresholds. J Speech Hear Disord. 1959;24:330–345. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ANSI . American National Standards Institute; New York: 1999. Maximum permissible ambient noise levels for audiometric test rooms. [Google Scholar]