Abstract

As outsourcing ventures become more complex, opportunities for synergies and efficiencies increase, but also create longer and more fragmented supply chains which could have disastrous consequences, particularly in a healthcare context. This study investigates the implications of outsourcing on healthcare supply chains by comparing two alternatives: outsourcing from public-to-private and outsourcing from public-to-public. A conceptual framework, adapted from previous literature, has been employed to provide a comprehensive overview of the phenomenon and consider the implications of logistics and procurement outsourcing on the healthcare supply chain structure and performance. The study presents a European cross-country comparison, analysing both the National Health Service (NHS) outsourcing in England (public-to-private outsourcing) and the Regional Health Service (RHS) outsourcing in the Tuscany region (Italy) (public-to-public outsourcing). Specificities and commonalities of the two outsourcing experiences provide suggestions for managers and policy-makers and enhance the current knowledge of outsourcing in the public healthcare sector.

Keywords: Logistics, Procurement, Outsourcing, Public sector, NHS England, RHS Tuscany

1. Introduction

The use of outsourcing by the public sector has increased dramatically in recent times (Beaulieu, Roy, & Landry, 2018; Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013; Kakabadse & Kakabadse, 2002; Lin, Pervan, & McDermid, 2007; Mori, 2017; Narayanan, Schoch, & Harrison, 2007) and the reasons for this are varied (Kremic et al., 2006; Leslie & Canwell, 2010). Outsourcing in the public sector can be defined as the act of a public organisation transferring internal activities/services and decision-making to external suppliers through long-term contracts or agreements (Rajabzadeh et al., 2008). While the immediate impetus for outsourcing reform in the public sector is the need to reduce government spending, there has also been a drive to model government on private business to achieve greater efficiency (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011; Van de Walle & Hammerschmid, 2011).

Public healthcare organisations in different countries have increasingly come to view outsourcing as critical to successfully provide quality care within the confines of an era of fiscal constraint (Beaulieu et al., 2018; De Vries & Huijsman, 2011; Jarrett, 1998; Nicholson, Vakharia, & Erenguc, 2004). Given the increasing health costs facing all industrialised countries, the search for possible savings has been a driver of strategic and organisational changes that increase efficiency and wellbeing without undermining the quality of and access to care. However, outsourcing in the public sector has often been plagued with failures and problems (Sullivan & Ngwenyama, 2005) such as impossible tendering timetables, dubious savings claims, deep dissatisfaction, non-delivery of service levels, and failure to properly monitor the contracts (Amirkhanyan et al., 2007; Marco-Simó & Pastor-Collado, 2020; Martin, 2001). Similar issues in public sector outsourcing have been reported in different countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Sweden (Peled, 2001; Sullivan & Ngwenyama, 2005).

The complexity of the outsourcing decision, coupled with the traditional rigidity of publicly founded organisations, calls for a deep analysis of the context, process and results of such a decision (Bustinza et al., 2010; Jiang, Frazier, & Prater, 2006). This analysis is even more necessary with regard to the healthcare sector, where little research has been conducted to investigate the large-scale implications of outsourcing (Beaulieu et al., 2018).

This study is positioned within the literature on outsourcing in public sector contexts. Specifically, the research aims to investigate the complexity of a specific type of outsourcing: the joint outsourcing of logistics and procurement functions in the healthcare public sector. Since the middle 1990s, supply chain management has been considered a possible source of savings for healthcare systems (De Vries & Huijsman, 2011). More recently, the grip on public expenditure has highlighted how much value is scattered in inefficient and redundant public procurement activities of healthcare organisations in most of the OECD countries (Lega et al., 2013). Although the adoption of an integrated supply chain management approach is becoming more common in the healthcare sector (Villa et al., 2009), the process of outsourcing has rarely been designed with the intention of investing in an end-to-end supply chain. Most outsourcing experiences in the healthcare sector concern only one of the two processes – either logistics (e.g., Beaulieu et al., 2018) or procurement (e.g., Lega et al., 2013) – and focus on specific issues such as the outsourcing of inventory management (Moschuri & Kondylis, 2006; Nicholson et al., 2004).

As outsourcing ventures become more complex, opportunities for synergies and efficiency increase, but also create longer and more fragmented supply chains which could have disastrous consequences, particularly in a healthcare context (Kremic, Tukel, & Rom, 2006; Lee, 2017; Sullivan & Ngwenyama, 2005; Yigit, Tengilimoglu, Kisa, & Younis, 2007). As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to unfold, the capabilities of supply chains are coming into sharp focus, not so much in terms of cost efficiency, but on their ability to be resilient and effective in delivery (Alicke, Azcue, & Barriball, 2020). This is why understanding the potential implications of complex outsourcing in the healthcare sector is of paramount importance.

This study is designed to fill the gap in our understanding of the implications of outsourcing on healthcare supply chains by comparing two outsourcing alternatives: outsourcing from public-to-private and outsourcing from public-to-public to address the research question: What are the critical aspects of the joint outsourcing of logistics and procurement in the healthcare public sector?

A conceptual framework, adapted from previous literature (Marasco, 2008), has been employed to provide a comparative investigation of the phenomenon and consider the implications of logistics and procurement outsourcing on the healthcare supply chain structure and performance. The study presents a European cross-country comparison by analysing both the National Health Service (NHS) outsourcing in England (public-to-private outsourcing) and the Regional Health Service (RHS) outsourcing in the Tuscany region (Italy) (public-to-public outsourcing).

The NHS is both the oldest and largest single-payer1 health system in Europe. In October 2006 procurement and logistics were jointly outsourced to a private sector logistics specialist in order to increase efficiency with an end-to-end supply chain control. The Tuscany region case shows a different pattern to outsourcing in the healthcare sector. Here, the search for efficiency led, in 2005, to the creation of a centralised publicly founded agency to which procurement and logistics have been outsourced from the healthcare organisations.

Beyond the fact that the two cases share the same rationale (to build, through outsourcing, a centralised end-to-end supply chain management structure for the health system) and were developed in the same time period, they are different by nature: in the NHS case a private sector service provider was involved, while in the RHS a public organisation was established as the outsourcee. Such differences are likely to shed light on issues overlooked in previous studies and contribute to the development of more exhaustive recommendations for managers.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, a literature review is presented and the theoretical framework justified for the study. Second, a description of the study methodology is provided. Third, the case studies are presented and discussed, then conclusions and recommendation are drawn. Finally, limitations and areas for future work are identified.

2. Literature review and theoretical framework

Two important contextual aspects are discussed in this section, which are then later analysed within the cases: first, the specificities of the public sector in relation to outsourcing and second the specificities of the healthcare sector, which are both relevant to logistics and procurement. The final sub-section introduces the theoretical framework used to analyse the two case studies.

2.1. The public sector and outsourcing

Despite its growing popularity, outsourcing to the private sector has been a relatively recent phenomenon in the public sector, emerging in the early 1990s and increasingly employed as part of broader privatisation movements (Augurzky & Scheuer, 2007; Beaulieu et al., 2018; Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013; Mori, 2017; Young, 2007). The trend towards outsourcing from the public to the private sector indicates that they are distinct and fundamentally different. Supporters of the view that public management is different (Boyne, 2002; Lukrafka et al., 2020) have identified a number of characteristics that are distinct between the public and private sector.

First, public organisations have a wide variety of stakeholders who exert demands and constraints on managers. The presence of different stakeholders (e.g. suppliers, service users and taxpayers) requires public organisations to pursue a range of, and sometimes conflicting, objectives (Arlbjørn & Freytag, 2012; Burnes & Anastasiadis, 2003). Moreover, it has been argued that public organisations have different goals from those of the private sector, such as ethics, equity or accountability (Arlbjørn & Freytag, 2012; Flynn, 2007), although the institutional mission of public organisations is to meet stakeholder expectations (Moore, 2000). These broader objectives have a significant impact on the way in which specific functions (e.g., logistics and procurement) are developed within public sector organisations and often require the evaluation of these operations in terms of much broader parameters that are related to the achievement of public interest. For instance, often public logistics is outsourced to improve efficiency, but equally it creates issues of equity and ethics when employees are no longer civil servants and become employees of a private contractor (Moschuri & Kondylis, 2006).

Second, public sector organisations have more formal, less flexible and more risk-averse decision-making procedures than do their counterparts in the private sector (Bozeman & Kingsley, 1998; Farnham and Horton 1996; Vyas, Hayllar, & Wu, 2018) because they tend to be designed around the principles of the bureaucratic model. For example, public contracts are often awarded on the basis of rules and principles that are designed to ensure equal supplier treatment, non-discrimination, and transparency, to reduce the risk of corruption (European Parliament, 2014). As described by Moore (1995), typically in the case of public organisations the value added is not the actual result accomplished but instead it is derived from how the procurement process itself is designed and executed. The respect of laws and regulations, in the execution of the procurement process, is necessary in order to meet public goals such as equity, accountability and no corruption (European Parliament, 2014; Sargiacomo, Ianni, D’Andreamatteo, & Servalli, 2015). However, this more bureaucratic model could reduce efficiencies and increase overall advertising and tendering costs (Doerner & Reiman, 2007; Vyas et al., 2018).

Third, public healthcare organisations have some benefits compared to private organisations. For instance, public organisations are often more willing to introduce drastic changes because they do not fear losing their market share and cannot go bankrupt (Arlbjørn & Freytag, 2012; Borgonovi, 2005). Further, public organisations are expected to collaborate and to share their knowledge and practices; therefore, collaborative purchasing and network creation should be stronger for these organisations (Schotanus & Telgen, 2007; Vyas et al., 2018). Finally, public organisations can impose regulations on suppliers that positively influence their willingness to collaborate in a direct (through specific norms) or indirect (through moral persuasion) way (Arlbjørn & Freytag, 2012; Borgonovi, 2005; Dimitri et al., 2006). The increased level of collaboration can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the public supply chain.

2.2. Logistics and procurement in the healthcare sector

Among the different non-clinical activities, logistics and procurement are of great importance as they represent a large portion of healthcare organisations’ expenditure and are essential for their operational performance (Azzi et al., 2013; Beaulieu et al., 2018; Edler & Georghiou, 2007). Procurement and logistics outsourcing have been considered useful to simplify the procedures for finalising contracts, to encourage competition between supplying firms through transparent selection practices, and to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the entire healthcare system by increasing economies of scale and scope (Figueras et al., 2005; Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013).

This highlights the importance of considering logistics and procurement outsourcing in the healthcare sector, but what are the specific challenges faced by these operations in this context? It is said that healthcare processes exhibit high levels of variability due to a number of factors (Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013; Litvak & Long, 2000; Macinati, 2008; Noon et al., 2003): a) clinical variability due to the nature of different diseases, severity levels and the responses to treatment; b) demand variability resulting from the unpredictability of certain patient flows (e.g. accident and emergency); c) care professional variability because of different preferences, approaches and levels of ability. As a consequence of these characteristics, healthcare providers often believe that it is more difficult for them to predict consumption (Azzi et al., 2013; Jarrett, 1998; Vissers et al., 2001). However, while there is some evidence to support this notion, many scholars argue otherwise (e.g. Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013; Haraden & Resar, 2004; Vissers, 1998; Walley & Steyn, 2006) claiming that a significant proportion of this variability can be reduced through the use of organisational strategies such as using standardised clinical pathways for homogeneous groups of patients or better capacity management, lean thinking, and scheduling systems. The accompanying reductions in variability and increased standardisation in processes would create increases in efficiencies and reductions in costs in the healthcare supply chains.

Another specific challenge for the healthcare sector is that many supplies, such as medicines, require special precautions; for instance, they require storage within certain temperature ranges and have short shelf lives (Azzi et al., 2013). Further, there is a propensity to stockpile supplies, because in the past they have been affected by supply disruptions (Mazzocato, 2007; Saccomano, 1996).

It is also widely reported that clinicians are resistant to following organisational rules and procedures, claiming that they are devoted to good patient outcomes, rather than organisational performance. Often they cite product standardisation and supply base reduction as factors that undermine the quality and personalisation of treatment (Cox et al., 2005).

Finally, although cost savings and service quality improvement appear to be the overriding motivations for outsourcing from public to private sector (Amirkhanyan et al., 2007; Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013; Macinati, 2008), the success of outsourcing also depends on a number of different factors (Ellram & Edis, 1996; Guimarães & de Carvalho, 2013). In fact, hidden costs of outsourcing occur in selection, managing the relationship between supplier and outsourcer, and making changes to the service contract, all of which can offset any cost savings and quality improvements identified at the start of the outsourcing contract (Johansson & Siverbo, 2018; Young, 2007). We assess this through the use of a theoretical model, as described in Section 2.3.

2.3. The conceptual framework

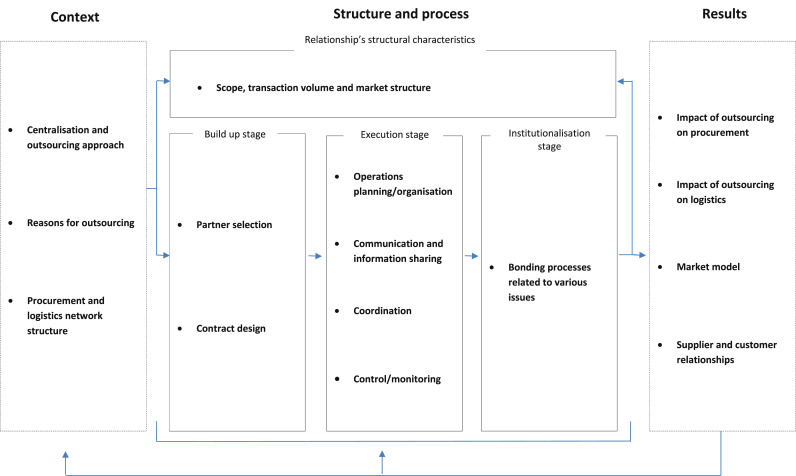

Based on a literature review, Marasco (2008), and later Beaulieu et al., 2018, presented a comprehensive conceptual framework that can be adapted to investigate the entirety of an outsourcing process, including background, implementation steps, governance structure and results. This conceptual framework provides a comprehensive overview of outsourcing as it includes all the aspects mentioned by previous literature on the topic (Leuschner et al., 2014). Since the Marasco (2008) framework was constructed based on a review of inter-organisational relationships literature, in this study it is applied to the inter-organisational relationship between the outsourcer and the logistics and procurement provider in the healthcare sector. According to the framework, the outsourcing process can be investigated across three different dimensions: context; structure and process; results.

Context dimension includes both external and internal factors. Major components of the external context include characteristics of the general macro environment (e.g. economic trends, regulatory framework, technological developments) as well as the supply chain, or network, within which the outsourcing relationship exists (e.g. structure, processes, types of business links among actors in the chain) (Marasco, 2008). Internal contextual factors include organisational size, structure and strategies of the parties involved (i.e. outsourcer and provider). The two sets of contextual factors combine to influence the ways in which outsourcer and provider structure and manage their relationship, affecting, among others, those factors that determine the outsourcer’s logistics needs and motivation to outsource, and the interaction processes between the parties.

Structure and process have different components. The structure of the outsourcing relationship can vary widely depending on several attributes, such as scope of the activities involved, continuity, complexity, symmetry and degree of formalisation, which are some of the structural characteristics of business relationships (Håkansson & Snehota, 1995). Along with these, other behavioural attributes are covered here that contribute to shaping the climate of the outsourcing relationship (e.g., trust, commitment and conflict).

The developmental process of the relationship constitutes the third dimension of the framework. Consistent with the approach taken in many studies of developmental processes of inter-organisational relationships (e.g. Dwyer et al., 1987; Frazier, 1983; Ring & Van de Ven, 1994), the outsourcing process has been conceived as consisting of a sequence of stages, summarised as follows:

-

(a)

The early build-up stage, in which potential providers are selected by the outsourcer to negotiate and develop a (formal or informal) contract for the provision of logistics and procurement services.

-

(b)

The execution stage, in which the commitments and rules of action agreed upon by the parties in the previous stage are carried into effect; in this phase, operations are organised, executed, co-ordinated and monitored, entailing adaptations and increased experience between the companies of the respective activities.

-

(c)

A long-term stage, in which routine approaches tend to become institutionalised and several kinds of bonds between the parties arise or strengthen as a consequence of extensive formal and informal adaptations. These bonds have an important function in favouring the creation of long-term relationships and can relate to the technologies used and shared by the parties, personal knowledge and trust, administrative routines, procedures and legal contracts.

The final dimension of the framework reflects the outcomes that result from the outsourcing relationship. As inter-organisational relationships are connected, what is produced in a dyad has effects, not only for the parties directly involved, but also for other relationships and organisations of the overall network in which the relationship is embedded (Burnes & Anastasiadis, 2003). Accordingly, outsourcing outcomes have been divided into internal outcomes perceived by the parties directly involved (outsourcer and provider) and external outcomes experienced at the supply chain level.

3. Methodology

The overall aim of this study is to investigate the critical aspects of the joint outsourcing of logistics and procurement in the healthcare public sector. An exploratory case study approach was chosen because it allows the outsourcing phenomenon to be studied within its real-life context, since it is not possible to isolate this complex phenomenon from the context in which it exists (Yin, 2018). Consequently, an inductive research strategy was used in conjunction with the comparative case method (Ragin, 1987). This allows two cases of joint logistics and procurement outsourcing in the healthcare sector to be compared, using the dimensions of Marasco’s (2008) conceptual framework for outsourcing. The unit of analysis was the outsourcing process itself and, in both cases, data was collected, enabling differences in outcome to be evaluated against differences in the context, structure and process. Both quantitative and qualitative data was collected and analysed for both cases, such that the qualitative data provides an explanation for the quantitative measures, consistent with Eisenhardt’s (1989) inductive case study approach.

Marasco’s (2008) framework required minor adaptations to fit with the nature and scope of the two healthcare case studies, as shown in Fig. 1 . First, the context and outcome dimensions are split into internal and external aspects (Marasco, 2008); however, this categorisation is not useful for this research, as all contextual and outcome aspects are related to the internal supply network, therefore a more relevant categorisation of aspects was used, as shown in Fig. 1. Second, partner search and negotiation processes, under the build-up stage, are outside the scope of these case studies, which focus more on partner selection and contract design.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual outsourcing framework (adapted from Marasco, 2008).

The two healthcare cases were selected to provide diversity and thus improve the external validity of the findings (Yin, 2018), and enhance the potential for comparative case analysis (Ragin, 1987) as they are representative of two different outsourcing typologies:

-

•

First, the National Health Service (NHS) outsourcing experience in England, which is an outsourcing from the public to the private sector, employing a competitive free market model where the client organisations are not mandated to use the private provider.

-

•

Second, the Regional Health Service (RHS) outsourcing experience in the Tuscany region (Italy), which is an outsourcing from public to public sector where the client organisations are mandated to use the public provider.

These two cases were contrasting in terms of scale – national versus regional – and also scope – NHS England outsourced logistics and procurement for consumables, whereas RHS Tuscany included consumables and pharmaceuticals. However, the timing of the outsourcing was very similar. The NHS England outsourcing was implemented in October 2006 and the RHS Tuscany outsourcing was completed between 2005 and 2007, where procurement was outsourced in 2005 and logistics over the following two years. Qualitative and quantitative data was collected since 2005 (one year before the outsourcing) and for four years after the outsourcing process began, to show the trends in the measures and the outcome.

For the NHS England case, historic records of quantitative measures were sourced from NHS SC (the private provider) between January and March 2013. The majority of quantitative measures were provided for each contract year, October to September from 2006 (one year before the contract started) to 2010 (four years after outsourcing). In total, about 47 h of in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted (using an interview protocol covering the scope of Marasco’s framework), with 16 senior managers from NHS procurement and logistics organisations, between June and November 2008, July 2010 and April 2011, and January and March 2013. All interviewees were selected for their knowledge of both the outsourcing and logistics and procurement activities, and included personnel at multiple levels of the organisation. For the outsourcer, interviewees included the director of services, the head of research, the managing director of the supply chain management division, the commercial director and two purchasing managers. For the outsourcee, interviews included the chief executive officer, the chief finance officer, the finance director, the supply chain director and the procurement director.

Interviews were transcribed and then validated by each respondent. The quantitative data and information gained from interviews was compiled in a case study database and triangulated with NHS publicly available secondary sources to improve validity and reliability, such as official reports by NHS bodies (e.g., Department of Health, 2010; NHS, 2018) and the National Audit Office Report (NAO, 2011).

For the RHS Tuscany case, publicly available secondary sources were used to provide data for the quantitative measures for each calendar year from the beginning of 2003 (two years before the outsourcing to the ESTAVs2 ) to June 2009 (four years after the outsourcing began). These sources included: ESTAVs’ performance annual reports (2003–09), Lega, Marsilio, and Villa (2013), Panero, Calabrese, Campanale, Vainieri, and Nuti (2010) and Rapporto Oasi (2011). For the qualitative data it was not possible to gain access for interviews; however, the aforementioned publicly available secondary sources provided a rich source of information on the outsourcing, as demonstrated by the case analysis in Section 4. All the data from the public domain was cross-checked in order to assure its reliability and validity.

It is important to note that because some data was not available for both cases, certain comparative analyses were not possible. In particular, an in-depth comparison between the quantitative measures (in the procurement and logistics outsourcing results) was negated due to the absence of both a standard protocol for gathering information and a perfect match between the adopted metrics in the two cases.

4. Case studies analysis

In the next section the two case studies are analysed following the theoretical framework.

4.1. The NHS England outsourcing: from public to private sector

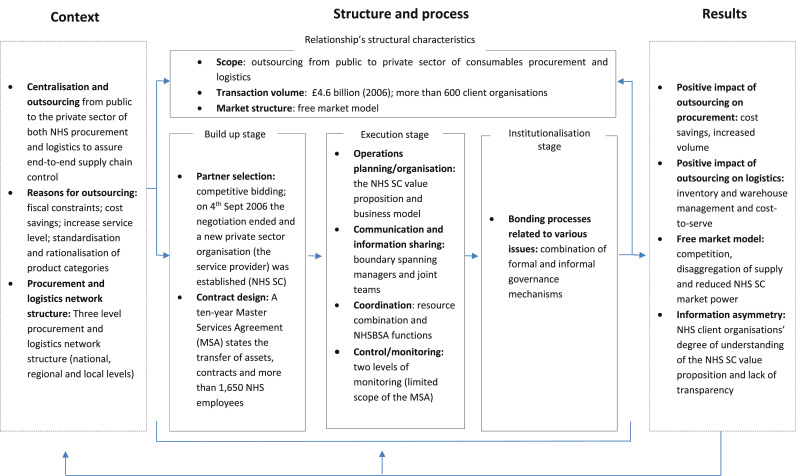

Fig. 2 summarises the main features of the NHS England outsourcing.

Fig. 2.

Logistics and procurement outsourcing process in the healthcare sector: the NHS England experience.

4.2. NHS outsourcing context

In 2006 the England NHS was experiencing three problems: first, the NHS organisations must keep a wide range of product in their inventories that are provided by a number of different suppliers; second, a proliferation of the product ranges often occurs because healthcare professionals may prefer using products that meet their own specification rather than using generic items; third, the NHS organisations’ internal procurement and logistics procedures are largely manual and scarcely developed (De Vries & Huijsman, 2011).

In addition, the NHS logistics and procurement landscape was a result of a series of government decisions, which resulted in a complex structure developed at three different levels (i.e., national, regional and local). At the national level, the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency (NHSPASA) – an executive agency of the Department of Health (DH) – aimed to negotiate national contracts covering everything from consumables to major pieces of scientific equipment, and provide supply guidance and support for NHS organisations’ procurement departments. A separate logistics organisation – the NHS Logistics Authority (NHSLA) – provided logistics services and supply chain management to the existing supply channels into the NHS on a non-profit making basis. At the regional level Collaborative Procurement Organisations (CPOs) were created, on a voluntary basis, as procurement organisations that accelerate savings through collaborative purchasing on behalf of their NHS member. At the local level, NHS client organisations operate within a free market framework according to which they are free to choose among different supply channels at national and regional levels as well as to source from direct suppliers or healthcare distributors autonomously.

In 2004, the DH decided to set up competitive tendering for the outsourcing of procurement and logistics to ensure end-to-end supply chain control, increase sales and thus assure financial benefits for the NHS. The outsourcing included the transfer of resources from public to private sector according to a ten-year Master Services Agreement (MSA) with a specialised logistics provider (Exel). The MSA was signed in the name of NHSBSA (acting as outsourcer) on September 4, 2006. A new organisation was established: NHS SC, a private organisation totally owned and operated by Exel, which was invested with the procurement and logistics responsibilities previously managed by NHSPASA and NHSLA respectively.

4.2.1. NHS England outsourcing structure and process

The DH made the selection of the service provider through competitive bidding. Both the NHS logistics and procurement, for consumable and clinical products, were jointly outsourced and the MSA was developed to govern the outsourcing relationship. The MSA specified the respective service performance targets with an overall objective of £1 billion savings in ten years. The outsourcing included the transfer of NHS assets and contracts, the granting of the right to use certain intellectual property, and the transferring of nearly 1650 NHS employees (procurement and logistics staff).

NHS SC provided a dedicated supply chain to the English NHS by operating a logistics infrastructure, including seven large distribution centres. They provide end-to-end supply chain services for the in-scope product categories incorporating procurement, logistics, e-commerce, and customer and supplier support. Procurement responsibilities include putting tenders out to the marketplace, evaluating suppliers, negotiating and managing the contracts, and managing the NHS online catalogue.

The MSA only partially governs the outsourcing relationship. Its scope is particularly limited, and therefore it is referred to as an agreement, as opposed to a contract. The MSA service performance targets are limited to:

-

-

Delivery on time of 98.75% (and for 5 h emergency response service 99.5%);

-

-

Delivery in full of 98.20% (and for 5 h emergency response service 99.5%);

-

-

On-time in full at order level of 82%;

-

-

Creditor/debtor payment days of 28–33 days.

The value proposition of NHS SC is to deliver price reductions and internal operating efficiency improvements derived from procurement and contracting, electronic ordering, consolidated invoicing and integrated Pay (P2P) systems, and consolidated deliveries.

The outsourcing arrangement seeks to benefit from the combination of complementary resources retained by the outsourcer (NHS) and the specialised logistics provider (NHS SC). The resource alignment has been realised through a process of transferring specific resources from the public sector – such as delivery vehicles, distribution centres and employees – to the specialised service provider. These NHS resources have been combined with the service provider’s resource endowment – i.e., logistics, IT infrastructure and technical expertise – to obtain synergies from complementary assets and competences.

Furthermore, NHS SC has made additional investments in physical assets and specialised staff to accomplish outsourcing goals. Specifically, the procurement team competence was developed through the recruitment of procurement professionals from the private medical retail sector to complement existing public sector expertise inherited by the NHS. The Original Business Case provides a capital investment plan, which details annual investments over the 10 year contract across a number of assets: the vehicle fleet, distribution centres and information technology. NHS SC also provided supply chain innovation as evidenced, for example, by the rapidly expanded product range and the supplier innovation scorecard. However, the NHS SC also benefitted from the consolidated competence of employees coming from the public sector procurement area in which the service provider has limited experience.

The outsourcing relationship management required a combination of formal and informal governance mechanisms to be effectively managed. In fact, much more than conventional contract management is required for the outsourcing to succeed under an agreement (MSA) which is not a conventional contractual arrangement or business model. While providing control and guidance, the public sector outsourcer must maintain a balance to allow NHS SC the freedom to operate, innovate and be accountable for its actions, decisions and business performance. According to the NHSBSA Director of Services, “this is a fine balance which needs to be continually reviewed, setting it against greater need for transparency and collaboration, to improve efficiency and drive out short term operating costs, whilst meeting the needs for government spending targets with no loss of quality”.

The MSA established a joint working Committee (the “Joint Board”) for managing the outsourcing relationships and assure collaboration and information sharing. The Joint Board makes decisions regarding: changes to the MSA provisions; distribution of surplus to the client organisations; and monitoring of the performance measuring system. The Joint Board is appointed to review and discuss NHS SC business strategy and operations but cannot approve or dictate strategy as this would transfer risk back to the public sector. To manage the outsourcing agreement, boundary-spanning managers operating both in NHSBSA and NHS SC have daily contact at an operational level, supported by periodic meetings established by the service contract. They are grouped into three distinct teams (“Joint Teams”), respectively focusing on operations, strategy and finance. The boundary spanning managers have experience in both public and private sector logistics and procurement, and are primarily accountable for the review of the outsourcing relationship to maintain it as flexible and collaborative. They work closely to provide guidance and compensate for contractual gaps, and evaluate outsourcing contract criticalities and extensions.

Beyond formal control, NHSBSA also performs three important functions to assure coordination between the service provider and the NHS client organisations. First, NHSBSA carries out ad hoc interventions to solve exceptional issues or problems. Second, NHSBSA performs the translation of government policy into the context of the outsourcing business model, which requires an in-depth understanding of the NHS SC legacy business, best practice supply chain and procurement solutions. Third, NHSBSA also manages “many-to-many” relationships with multiple stakeholders.

In the NHS, the performance evaluation system is not only designed to ensure that NHSBSA monitors NHS SC’s performance against the MSA targets, but it also includes a complex set of procurement and logistics measures which are assessed on a daily or weekly basis and reviewed at the monthly Operations Joint Team meeting and quarterly Joint Board meeting. Of these measures, only the quality of the NHS SC delivery service to the NHS client organisations and the creditor and debtor purchase to pay times are monitored against targets in the MSA, and the sales and price savings targets are monitored on a non-contractual basis. Other financial targets are monitored periodically, including the planned capital investment and an annual profit cap. Qualitative information, concerning for example procurement’s tender pipeline, customer satisfaction, and the service provider’s competitive position, are also monitored on a continual basis. These monitoring systems help resolve the trade-off between the importance of governmental control over the outsourcing, and the autonomy of the service provider’s strategic orientation.

4.2.2. NHS outsourcing results

The outsourcing from public to private in the NHS case was considered successful. NHS SC transacted sales have grown significantly since 2006 and, by March 2010, cumulative sales (including capital sales) were £1.5 billion, just £100 million short of the target in the original business case. Most importantly, from the NHS perspective, the cumulative price savings delivered to the NHS were above target up to October 2009, in excess of £70 million.

In aggregate terms, the most relevant improvements from 2005 to 2010 are the following:

-

⁃

an increase in purchasing volumes (+37%) with a cumulative price saving (−88%)

-

⁃

an increase in NHS client organisations’ price savings (from 1.4% to 7.4%)

-

⁃

an increase in the number of product lines available (+91%)

-

⁃

an increase in sales per NHS client organisation (+52%)

-

⁃

a reduction in DC stock cover (average per year) (from 3.18 to 2.62 weeks)

-

⁃

an improvement in logistics metrics (+35% fleet utilisation; −26% cost-to-serve)

-

⁃

an increase in procurement staff (191 in 2010, almost quadrupled in size since 2006).

Table 1 shows the trend of the procurement and logistics data from 2005 (before the outsourcing) to 2010.

Table 1.

Logistics and procurement improvements in the NHS experience (2005–2010).

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumable and clinical sales to the NHS (£million) | n.a | £ 829 | £ 936 | £ 1092 | £ 1206 | £ 1317 |

| NHS Trusts price savings from NHS SC (% of sales) a | n.a. | 1.40% | 4.20% | 6.90% | 4.70% | 7.40% |

| NHs prices savings cumulative | n.a. | £ 12.00 | £ 39.00 | £ 75.00 | £ 57.00 | £ 97.00 |

| On-line catalogue listing (No. Of lines available) | 50,345 | 58,220 | 68,006 | 542,858 | 640,425 | 654,775 |

| Delivery on time (%) | n.a | 99.49 | 99.11 | 99.31 | 99.14 | 98.36 |

| Product availability (%) | 98.23 | 98.3 | 98.34 | 98.67 | 98.67 | 98.72 |

| On time in full (%) b | n.a | 86.64 | 88.3 | 88.94 | 89.08 | 88.77 |

| DC stock cover in weeks (average per year) | 3.18 | 2.65 | 2.92 | 2.85 | 2.69 | 2.62 |

NHS Trust price savings from NHS SC = {base line selling price (adjusted for inflation using the ONS quarterly indices) – today’s selling price} x volume sold by NHS SC. The base line for prices was established from a snapshot of prices on October 1, 2006. For new products no base line exists so it is created with the initial prices. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) quarterly indices is an aggregate indices.

The OTIF measure = % orders delivered in full x % orders delivered on time x % Customer Management System issues.

NHS SC is also providing savings for the NHS on logistics and transaction costs. Its management of the procurement process negates a client organisation’s need to tender through the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU).

Despite such positive outcomes, the NHS outsourcing presents a number of challenges. Firstly, one of the most evident effects of the outsourcing has been an increase in competition, promoted by the free-market model where the NHS client organisations are free to choose from all available sourcing options. This leads to disaggregation of supply where all the procurement entities – healthcare organisations, NHS SC and collaborative procurement organisations (CPOs) – are frequently sourcing from the same suppliers. This disaggregates the volumes, reducing the buying power of the NHS, and could thus allow the suppliers to sell at a higher price. The estimation of the NHS SC market share at the end of 2010 reflects the high level of competition (Table 2 ), and shows NHS SC has not reached 50% market share.

Table 2.

NHS SC estimated market share for the year April 2009 to March 2010 for in-scope consumables categorised according to NHS SC organisation structure (Source: NHS SC).

| NHS SC Sales (£million) | Mkt sales (£million) | NHS SC Share |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Care – Medical and clinical markets | 610 | 2613 | 23% |

| Patient Care – Foods and facilities (non medical) | 340 | 736 | 46% |

| Theatres | 225 | 515 | 44% |

| Diagnostics (mainly capital medical equipment) | 338 | 736 | 46% |

| Total | 1513 | 4600 | 33% |

Note: The total in-scope consumables spend in NHS England of £4.6 billion is sourced from the NAO report (2011), while the market breakdown is estimated by the NHS SC based on market intelligence.

The challenge for NHS SC to continually increase its market share is hindered by its unique position in the marketplace. Unlike its competitors, the NHS SC competes in all product categories, but was constrained to supplying NHS organisations only, as specified in the MSA. In contrast, NHS SC’s competitors can focus efforts on specific categories to optimise their revenue and profit margins. Further, all organisations procuring for the NHS are required to advertise tenders in the OJEU; however, unlike NHS SC, other organisations are not procuring at a national level, therefore their tenders may not exceed the OJEU thresholds and not require the resource-intensive process of tendering through the OJEU.

The increase in competition has also led to an overwhelming supply choice for the NHS client organisations, which also found difficulties in distinguishing between the supply offers due to a lack of cost transparency. Besides, NHS SC has radically expanded their catalogue – also proposing a reduction in the number of product variants available – in order to increase aggregation of volumes and their ability to negotiate reduced supplier prices. In many cases, this rationalisation of product categories was perceived by the NHS client organisations as limiting the flexibility necessary to address the patient care objectives and was counterbalanced by an increase of direct suppliers’ procurement practices, mostly for specialist products and equipment. A lack of support and guidance by the NHS governance exacerbated the situation and contributed to the increase in differentiated procurement practices within the NHS client organisations (NAO report, 2011). The cumulative effects of the above factors can be recognised as an information asymmetry problem between all the actors involved.

4.3. The RHS Tuscany outsourcing: from public to public sector

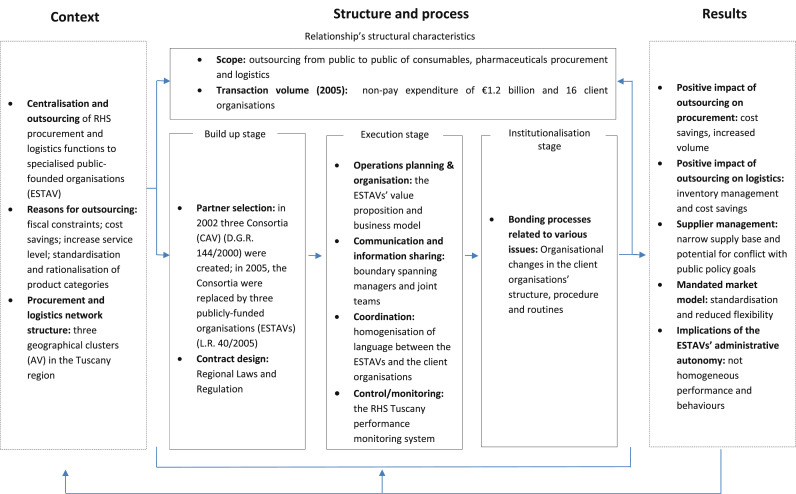

Fig. 3 summarises the main features of the RHS Tuscany outsourcing.

Fig. 3.

Logistics and procurement outsourcing process in the healthcare sector: the RHS Tuscany experience.

4.3.1. RHS Tuscany outsourcing context

Similarly to other European countries, the Italian national healthcare system has undergone major reforms in the last two decades, including managerialism and decentralisation of health policy responsibilities to the intermediate level of government (21 Regions, with an average population of three million people and a healthcare expenditure of €5200 million). The Central Government has exclusive power to set system-wide rules, while Regions have responsibility for the organisation and administration of their healthcare system and, partially, for funding the healthcare expenditure.

In recent years, many Italian RHS have reorganised non-clinical processes through the centralisation and outsourcing of several services, with particular attention given to procurement and logistics (Lega et al., 2013). The model adopted in the Tuscany region was the first launched across Italy and is viewed as a benchmark for integrated supply chain management initiatives in the Italian healthcare sector (Brusoni & Marsilio, 2007; Del Vecchio & Rossi, 2004). The Tuscany region’s experience of centralisation and outsourcing (from public to public) is also representative of the current trend in Europe towards the creation of platform (publicly founded organisations3 ) offering integrated procurement and logistics services to a network of healthcare client organisations (De Vries & Huijsman, 2011).

The RHS Tuscany includes several entities, specifically: 12 Local Health Authorities4 and four (independent) University Clinical Centres – Teaching Hospitals. The average annual non-pay expenditure of Tuscany RHS from 2005 to 2009 varied from €650 million (2005) to €1.4 billion (2009) for a population of about three million (Rapporto Oasi, 2011).

4.3.2. RHS Tuscany outsourcing structure and process

In 20005 the RHS Tuscany started a process of centralisation of consumables and pharmaceutical procurement with the following aims: a) reduce and rationalise the supply base; b) standardise the product categories; c) increase efficiency and reduce supply and administrative costs. The centralisation became operative in 2002 with the creation of three different geographical clusters (named “Area Vasta”, AV) into the Tuscany region, each of them governed by three Consortia. The Consortia retained a certain degree of autonomy for contract negotiation and purchasing aggregation on behalf of the RHS client organisations. They also employed half of the procurement staff transferred from the RHS organisations (more than 150 employees).

The rationale behind the creation of the AVs is to incentivise a collaborative approach6 in an era of fiscal constraints. However, after two years of trial, the nature of the Consortia – which were regulated by private sector rules – was under discussion by the regional government. The major issue was the status of the public employees transferred from the RHS organisations (public sector) to the Consortia (a private sector-assimilated organisation). Such imbalance of employee status raised a number of legal issues and organisational implications. To solve the question, in 2005 the Consortia were replaced by three publicly founded organisations named ESTAVs (“Enti per i Servizi Tecnico Amministrativi di Area Vasta”) (L.R. 40/2005). The three ESTAVs7 were part of the regional healthcare system with a specialised service role. The main responsibilities of each ESTAV were the centralisation and rationalisation of procurement and other functions on behalf of the LHAs localised respectively in each of the three AVs.

A regional law (L.R. 40/2005) detailed the main responsibilities of each ESTAV as follows: procurement of good and services; logistics and warehouse management; management of IT infrastructure; facilities and real estate management; human resource management (payments and careers development); and management of bidding and auctions.

Since 2005 (the establishment of the three ESTAVs) the Tuscany healthcare system started a progressive outsourcing of all the functions mentioned in the L.R. 40/2005 from the LHAs and independent Hospitals to the ESTAVs. Part of procurement outsourcing was already started with the creation of the Consortia but the establishment of the ESTAVs (in place of the Consortia) revised the process. The outsourcing took several years to be completed (in fact, in 2005 only procurement activities were outsourced to the three ESTAVs) and a series of additional regulations were needed in order to activate the actual transfer of each specific function. Specifically, two regional law were promulgated to transfer logistics (D.G.R., 617/2006) and IT infrastructure (D.G.R., 317/2007). The process was complicated by the public nature of all the actors involved, whose rigidity and inertia slowed down the reorganisation process.

Contrary to the NHS experience, the RHS client organisations were mandated to delegate procurement and logistics activities to the service provider (ESTAVs). Two regional laws (L.R. 40/2005 and D.G.R. 1021/2005) govern the outsourcing relationships and provide indications regarding the transfer of assets, contracts and employees. The value proposition of each ESTAV recognised that they aim to deliver price reductions and internal operating efficiency improvements derived from EU-compliant procurement and contracting, electronic ordering or online catalogue, and consolidated invoicing and delivery (Panero et al., 2010). The ESTAVs were organised with departments specialised in specific product categories: in-scope product categories, pharmaceuticals, capital equipment, vehicles, hardware/software, and other services. This departmentalisation has the objective to increase specialisation and operational efficiency through economies of scale.

The governance of the outsourcing process remained entirely within the ESTAVs, with a specific Committee in which representatives of the client organisations take part. The Committee had responsibilities for planning, demand forecasting and control of the centralisation and outsourcing results. The way in which the process has been developed has impacted significantly on the client organisations’ freedom to operate. In fact, the business strategy and the operations are developed at the ESTAV level, with reduced possibilities for each client organisations to contribute with specific requests and dedicated arrangements. At the same time, the process of centralisation of requests requires the client organisations to equate their internal processes to the timing and procedures developed by the service provider. This requires a fine balance between freedom to operate and adherence to a centralised system with some degree of standardisation (Brusoni & Marsilio, 2007). One of the most critical issues of the outsourcing process was the homogenization of the procurement (and consequently logistics) language: each client organisation needed to update and standardise their database in order to interface with the ESTAVs.

To increase the communication and translate the public policy into the context of the outsourcing business model, the Committee’s representatives act as boundary spanning managers: they work closely and extensively to provide guidance and compensate for bureaucratic rigidity, and to evaluate centralisation and outsourcing criticalities and extensions (Del Vecchio & Rossi, 2004). Furthermore, representatives from the client organisations are included in Joint Teams built to activate each procurement process (bidding and supplier evaluation activities); this increases process transparency and contributes to the realisation of economies of scale in logistics and procurement. The Joint Teams were developed with a certain degree of heterogeneity (for example, procurement experts work with doctors and financial deputies) to reduce the disaggregation of supplies and increase the buying power of the ESTAVs.

A performance evaluation system was developed and implemented starting in 2005. The system was intended to measures the quality of services provided and the capacity to meet citizens’ needs to achieve better health and quality of life standards on the one side and, on the other, to preserve financial equilibrium. The number of indicators and metrics adopted is wide, spanning from customer satisfaction to demand management8 . The evaluation system includes a set of procurement and financial measures which are assessed on a periodic basis and reviewed at the ESTAVs’ Board meetings. Qualitative information, concerning, for example, procurement’s tender pipeline, customer satisfaction and the service provider’s catalogue expansion, are also monitored on a continual basis (Cinquini et al., 2015). Moreover, healthcare top management and professionals are also actively involved in the performance evaluation process. On the one side, they are involved in the indicator definition and refinement process; on the other side, they are called to participate in the organisational climate survey, which is carried out about once a year within all Tuscan health organisations (Nuti et al., 2013).

In the institutionalisation stage, the main challenges were the requalification of the ESTAVs’ employees and the reorganisation of the healthcare organisations’ structure. Contrary to what happened in the NHS, in Tuscany the resource endowment of the service provider come entirely from the public sector, although it has been slightly enriched with investments in assets and staff starting from 2006. The majority of the ESTAVs’ staff were previously employed within the client organisations. Only some of them had experience and competences in specific areas such as purchasing, and logistics departments of healthcare organisations are typically functional units staffed by generalists who lack specific education and training (Callender & McGuire, 2007). Consequently, in 2005 each ESTAV started a massive process of requalification and specialisation of procurement and logistics staff (Dominijanni & Nante, 2007; Rapporto Oasi, 2011).

Within the healthcare organisations, the loss of some of the transferred employees stimulated a process of reorganisation to reduce the overlaps and relocate staff to other value-adding activities. For example, as suggested by Lega et al. (2013), the centralisation of logistic activities within the ESTAVs’ warehouses had been seen as a unique opportunity to relieve hospital pharmacists from operational responsibilities and increase their involvement in clinical activities. However, this process was neither easy nor immediate, as they feared losing power and control over drugs management or other previously controlled activities.

4.3.3. Tuscany case outsourcing results

The outsourcing from the RHS organisations to the three ESTAVs was considered successful. The data and information in the public domain show, in aggregate terms, the following improvements for the entire RHS from 2003 to 20099 :

-

⁃

an increase in purchasing volumes (+56%) with consequent cost savings (7.8%);

-

⁃

an increase in the number of auctions (+12%);

-

⁃

a reduction in procurement administrative costs (−50%);

-

⁃

a reduction in logistics costs (for warehouse management10 ) (about €1.5 million);

-

⁃

a reduction in Full-Time Equivalents for about €12 million;

-

⁃

a reduction in inventories (−50% for a value of more than €60 million/year);

-

⁃

improvements in logistics metrics (+57% turnover ratio);

-

⁃

a reduction in procurement staff (−48%) and logistics staff (−60%).

Because of the economies of scale and scope, and the elimination of duplications and redundancies, the ESTAVs’ centralised model allowed operational cost savings and improvements in both procurement and logistics performance. Despite the differences in dimensions and procurement volumes,11 the three ESTAVs show similar positive trends for all the measures considered. Table 3 illustrates the changes in volume, value and cost savings for procurement of the Central ESTAV (Rapporto Oasi, 2011).

Table 3.

Central ESTAV procurement savings.

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 (until 30th June) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of auctions | 677 | 386 | 201 | 293 | 171 |

| Value of contracts (€Million) | 187 | 492 | 913 | 519 | 245 |

| Cost Savings (€Million) | 5.31 | 41.25 | 34.75 | 30.42 | 17.10 |

| Cost Savings (%) | 2.8% | 8.4% | 3.8% | 5.9% | 7% |

Source: Elaboration from Rapporto Oasi (2011).

The results provided by the performance monitoring system also confirm that the centralisation of procurement and logistics activities has guaranteed quality service improvements in different areas. The short length of the ESTAV model (with deliveries directly to hospital floors without a transit point) and the ability to share resources and technologies allow high levels of flexibility in terms of both capacity to meet demand variability and responsiveness (Lega et al., 2013).

Despite the improvements, the process of centralisation and outsourcing in Tuscany has presented a number of criticalities (Brusoni & Marsilio, 2007). Firstly, the performance and degree of maturity of the three ESTAVs is not homogeneous, with non-trivial implications for supplier relationship management. For example, Panero et al. (2010) show that in more than 37% of tenders activated in 2007 there was only one supplier involved, while 40% of the tenders involved two to five suppliers. Data suggests that the ESTAVs’ ability to involve multiple suppliers to tender was limited and the benefits for increased bargaining power not maximised. Besides, at the time of this study, payment days were increasing. Two possible explanations can be suggested: a) the potential for rationalisation in the number of suppliers has conflicted with the goal of supporting small and local suppliers; and b) delayed supplier payment could have been adopted as an explicit political strategy for sustaining cash-based accounting systems for public hospitals (Lega et al., 2013).

Secondly, the centralisation of functions and subsequent standardisation of processes have significantly reduced the freedom of operation for the healthcare organisations. They might suffer due to a reduction of the number of product categories available, which conflicts with the flexibility needed for such organisations to meet urgent or specific requests and unexpected changes (Noon et al., 2003). The mandated market model sharpened the effect of standardisation and made difficult for the healthcare organisations to address both the clinical variability and the care professional variability typical of such an industry (Walley & Steyn, 2006).

5. Discussion and contribution

The two outsourcing cases have commonalities and differences across the dimensions of Marasco’s conceptual framework. A comparative synthesis of the two cases is presented across three tables: Table 4 compares the ‘context’, Table 5 focuses on ‘structure and process’, and Table 6 contrasts the ‘results’ obtained in both cases.

Table 4.

Cross case comparison of NHS England and RHS Tuscany cases – Context.

| NHS England | RHS Tuscany cases | Comparison (commonalities and differences) | Explanation for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centralisation and outsourcing | Outsourcing from public to private sector organisation to assure end-to-end supply chain control | Centralisation and outsourcing to specialised public-founded organisations to assure end-to-end supply chain control | Tuscany operations required centralising before they could be outsource. Here, the decision to outsource to a public body was developed partially to solve legal and bureaucratic issues arisen after the procurement centralisation within the Consortia. | The decision to outsource to the private or public sector contemplates a number of political implications. The search for efficiency needs to be balanced with the objectives of equity, accountability and ethics, typical of public organisations |

| Reasons for outsourcing | Fiscal constraints; cost savings; increase service level; standardisation and rationalisation of product categories | Fiscal constraints; cost savings; increase service level; standardisation and rationalisation of product categories | The rationale behind the centralisation and outsourcing are similar for the NHS England and RHS Tuscany | |

| Procurement and logistics network structure | Three level procurement and logistics network structure (national, regional and local level) | Three geographical clusters (AV) in the Tuscany region | The Tuscany established three different public providers (one for each AV) with identical structure and functions, whereas the England private provider is a single organisation at a national level | The England case seeks to aggregate volumes and standardise products at a national level for economies of scale, whereas Tuscany is at a regional level. The presence of three ESTAVs generated non homogeneous outcomes |

Table 5.

Cross case comparison of NHS England and RHS Tuscany cases – Structure and Process.

| NHS England | RHS Tuscany cases | Comparison (commonalities and differences) | Explanation for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Outsourcing from public to private sector both the logistics and procurement of consumables | Outsourcing from public to public both the logistics and procurement of consumables and pharmaceuticals | In both case logistics and procurement were jointly outsourced, but the Tuscany outsource includes pharmaceuticals whereas the England outsource excludes them. | Pharmaceuticals are a large part of public expenditure. Due to the importance of such products, the Government maintains control over such category for ethical, equity and accountability reasons. |

| Transaction volume | £4.6 billion (2006) across more than 600 client organisations | Non-pay expenditure of €650 million∗ (2005) across 16 client organisations ∗includes consumables and pharmaceuticals |

Transacted volume and the number of client organisations are is far higher for the England case, however the expenditure for the Tuscany case is still sizeable | There is a significand difference in scale of the population served. In England the NHS serves over 50 million people, while in Tuscany the system covers under 4 million. |

| Market Structure | Free market model where client organisations are free to choose supply | Mandated market model where client organisations are mandated to buy from the ESTAVs | The England case is a free market model whereas Tuscany is a mandated model | The England case had previously operated on a free market model, and could not mandate public NHS organisations to buy privately |

| Build up stage | ||||

| Partner selection | Competitive bidding; on 4th Sept 2006 the negotiation ended and a new private sector organisation (the service provider) was established (NHS SC) | In 2002 three Consortia (CAV) (D.G.R. 144/2000) were created; in 2005, the Consortia were replaced by three public-funded organisations (ESTAVs) (L.R. 40/2005) | Competitive bidding was used to select the private provider in the England case whereas the Tuscany public providers were established by (regional) law | In the Tuscany case no alternative were available, with implications on the governance of the outsourcing relationship |

| Contract design | A ten-year Master Services Agreement (MSA) states the transfer of assets, contracts and more than 1650 NHS employees | Regional Laws and Regulation | A contract was established for the England case whereas the outsource could be governed by regional law for the Tuscany case | Outsourcing to the private sector required contractual assurances around asset transferred and scope of the activities such as the product categories, and service levels |

| Execution stage | ||||

| Operations planning/organisation | The NHS SC value proposition and business model aims to deliver price reductions and improvements to NHS client organisations. | The ESTAV’s value proposition of recognised that they aim to deliver price reductions and improvements to client organisations’ internal operating efficiency | Similar | |

| Communication and information sharing | Boundary spanning managers and joint Board and teams | Boundary spanning managers and joint teams | Similar | |

| Coordination | Resource combination and alignment between the outsourcer NHSBSA and the provider, NHS SC. | Homogenization of language between the ESTAVs and the client organisations | In the NHS case, public and private sector complementary resources were combined to create synergies. In Tuscany, the competences and resources were from public sector. | NHS SC capitalized on private sector experience during the outsourcing. This was not the case in Tuscany, where a massive process of requalification of ESTAVs’ employees was needed |

| Control/monitoring | Monitoring against limited MSA target plus complex set of measures | The RHS Tuscany performance monitoring system involved a wide range of measures | In both cases, a complex system of performance monitoring was developed. This demonstrate awareness about the risk of a lack of monitoring and the need to control the outcomes of such important decision | |

| Institutionalisation stage | ||||

| Bonding processes | Combination of formal and informal governance mechanisms | Organisational changes in the client organisations’ structure, procedure and routines | In both case, the outsourcing relationship governance required interventions that went beyond the formal mechanisms established by MSA and regional law. Such interventions were finalized to solve legal and organisational implementation issues (e.g. misalignment of resources, information asymmetry, homogenization of language and information) | |

Table 6.

Cross case comparison of NHS England and RHS Tuscany cases – Results.

| NHS England | RHS Tuscany cases | Comparison (commonalities and differences) | Explanation for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of outsourcing on procurement | Cost savings; Increased sales volume; rationalisation of product range was the reason for outsource | Cost savings; Increased volume and actions; reduction in administrative costs (staff) | Similar types and levels of impact | |

| Impact of outsourcing on logistics | Reductions in inventory cover and Cost-to-serve; Delivery service improved | Reductions in inventory, warehouse management costs and administrative costs (staff) | ||

| Market model | Free market modelling resulting in competition, disaggregation of supply and reduced NHS SC market power | Mandated market model leading to standardisation and reduced flexibility of supply | Both market model present opportunities and challenges. | Fundamentally different models. Free market model leads to competition and more choice. Mandated model leads to standardisation but reduced flexibility |

| Supplier and customer relationships | NHS client organisations need guidance to improve the understanding of the NHS SC value proposition. Lack of transparency increases the information asymmetry | The three ESTAVs struggle in developing effective supplier management system: narrow supply base and potential for conflict with public policy goals | High competition in the NHS reduces opportunity for volume aggregation and reduce prices. In Tuscany, the ESTAVs have a limited control over the supply base and are influenced by policy goals in developing supply management portfolio | In both cases a problem of information asymmetry affects the effectiveness of the process and impacts negatively on the bargaining power of the service provider. In both cases, more transparency and guidance are needed |

Both these cases can be considered to have positive outcomes (as shown in Table 6), but what are the critical aspects of the outsourcing structure and process that are common to both cases?

First, with regard to the context of outsourcing, in both cases both procurement and logistics were outsourced to enable end-to-end supply chain control and achieve desired cost savings, service levels, and rationalisation of procurement categories. This was aligned with the providers’ value propositions, which were also similar, and aimed to not only deliver price reductions but also improvements to client organisations’ internal operating efficiency. Both cases achieved significant logistics cost reductions, including inventory levels and warehouse management costs. However, the significant price savings of between 7% and 8% for the client organisations, would not have been achievable without the centralising and outsourcing of procurement to reduce supplier prices. This relates to the high levels of variability in healthcare processes due to clinical variability from different diseases, severity levels and the responses to treatment, and care professional variability because of different preferences, approaches and levels of ability (Litvak & Long, 2000; Noon et al., 2003). These variability factors drive increases in product variety, but by centralising procurement this variety can be rationalised across a bigger pool of client organisations and the demand aggregated onto fewer suppliers, thus driving reductions in prices. This contributes an important procurement strategy to the body of work that suggests high levels of variability in healthcare processes can be reduced through the use of organisational strategies (e.g. Haraden & Resar, 2004; Vissers, 1998; Walley & Steyn, 2006). The implications for practice are that centralisation of procurement through outsourcing is crucial for supplier price savings in the healthcare sector, regardless of whether it is a public or private organisation that performs the procurement.

The second critical and common aspect of these cases is grounded in the outsourcing structure and process and refers to the fact that the governance structure is a balance between a formal contract and informal governance mechanisms. Indeed, in both cases, much more than conventional contract management is required for the outsourcing to succeed. In the NHS case the MSA agreement covers limited aspects of the outsourcing, and only high-level performance targets, and in the Tuscany case the outsourcing was formally governed by regional laws and regulations, which were also very limited. Therefore, in both cases, the public sector outsourcers maintain a balance between providing control and guidance, and allowing the provider the contractual freedom to operate and innovate to improve performance. Further, the balance between control, and freedom to operate, ensures that the provider remains accountable for its actions, decisions and business performance, such that risk is not transferred back to the public sector outsourcer. This finding contributes to work by Narayanan et al. (2007) who suggest that for public outsourcing less formal governance mechanism and controls maybe more appropriate. Our work builds on this idea of informal controls by suggesting that the collaboration between the two parties is a fine balance between outsourcer control (and guidance) and allowing the provider freedom to innovate to promote the performance benefits. If the outsourcer exercises too much control then risk is transferred back to them and innovation is stifled, whereas too much provider freedom may lead to opportunistic behaviour as suggested by Kluvers (2003).

Still within the outsourcing structure and process, a third critical aspect can be highlighted. In both cases communication and information sharing between the outsourcer and provider were assured by boundary spanning managers and joint teams. Boundary spanning managers from the outsourcer and provider worked closely and extensively to provide guidance, compensate for bureaucratic rigidity and evaluate operating performance. Further, in both cases Joint Teams were established comprising representatives from outsourcer and provider organisations, in order to enable collaboration, transparency and flexibility across operations (logistics and procurement), finance and strategy for the NHS and procurement for the Tuscany case. This supports the idea that public organisations are expected to collaborate and share their knowledge and practices, and therefore collaborative purchasing and network creation should be stronger (Schotanus & Telgen, 2007). However, these findings go further by building on the work of Cox, Chicksand, and Ireland (2005) who suggest that boundary spanning managers may be necessary to ensure the outsourcing relationship remains flexible to changing needs and to compensate for the contract gaps. This work puts forward that when multiple functions (logistics and procurement) are outsourced Joint Teams, drawing from both outsourcer and provider and spanning functions beyond those outsourced, are necessary in order to enable transparency and flexibility.

With regard to the results, a fourth common aspect refers to the control and monitoring of performance, which in both cases involved a broad range of metrics and their periodic review by the Joint Board. For the NHS, performance evaluation system is not only designed to ensure that NHSBSA monitors the provider’s performance against the few MSA targets, but it includes a complex set of procurement and logistics measures which are assessed on a daily or weekly basis and reviewed at Joint Team and Board meetings. Similarly, in Tuscany, the performance evaluation system measures the quality of services provided, costs and the capacity to meet citizens’ needs across a wide range of metrics, which are assessed on a periodic basis and reviewed at the ESTAVs’ Board meetings. The requirement for a broad range of metrics stems from the wide variety of public organisation stakeholders (e.g. suppliers, service users and taxpayers) who require public organisations to pursue a range of, and sometimes conflicting, objectives (Burnes & Anastasiadis, 2003). This finding contributes to the literature that claims many public outsourcing experiences fail to deliver what is expected of them because organisations focus on the formal provisions (governmental rules and regulations) rather than systematically measuring and monitoring performance (Lin et al., 2007; Young, 2007). It suggests that the providers performance must be controlled and monitored, not just using a broad range of metrics, but by ensuring that these are regularly reviewed by a Joint Board populated by both outsourcer and provider representatives.

Complementary to these four common aspects a further two critical aspects are specific to each case. First, the alignment and combination of complementary resources between the NHS outsourcer and the private provider in the English case. Resource alignment was realised through transferring specific resources from the public sector – such as delivery vehicles, DCs and, most importantly employees – to the specialised service provider such that they can be combined with the service logistics provider’s resource endowment to develop a synergic combination of complementary assets and competences. Furthermore, the private provider made additional investments, including capital investments over the 10 year contract period according to the original business case. This suggests that both the private and public organisations were developing a shared long-term strategic view concerning the outsourcing resource and investment planning, demonstrating a mutual understanding of the need for long-term goals. This finding both confirms and extends research in outsourcing in a private sector context (Hindle, 2005; Webb & Laborde, 2005), recognising resource alignment and a shared strategic long-term view as critical success factors for public to private sector outsourcing.

The critical aspect specific to the Tuscany case relates to the providers (the three ESTAVs) being public organisations, which are consequently influenced by policy goals in developing supply management portfolios. For example, in more than 37% of ESTAV tenders activated in 2007 there was only one supplier involved (Panero et al., 2010) resulting in ESTAVs’ bargaining power not being maximised. Similarly, Lega et al. (2013) report that ESTAVs’ potential rationalisation in the number of suppliers, achievable through network procurement, may have conflicted with the goal of supporting small and local suppliers. The public nature of the ESTAVs implies that wider policy goals, such as supporting local suppliers, which benefit society, may sometimes override the procurement goal of appointing the most efficient and suitable supplier. This highlights the complexity of outsourcing in the public sector and the need to be mindful of the multiple policy goals that the public sector seeks to achieve when devising the structure and performance metrics during an outsourcing initiative.

6. Limitations and future research

This study contributes to the understanding of public sector outsourcing by analysing the critical aspects of the joint outsourcing of logistics and procurement in the healthcare system. The theoretical model – summarised in Fig. 1 – illustrates the overall process and outcomes and includes dimensions that are typically not relevant and/or critical in other contexts. Such specificities, articulated along with two different outsourcing experiences (i.e., outsourcing from public to private and from public to public sectors), provide suggestions for managers and policy-makers and enhance the current knowledge of outsourcing in the public healthcare sector.

As with any research, this study suffers from some limitations and areas that require further development. While the study takes a longitudinal perspective, the specific period of the analysis was constrained in both cases, and after the end of the study period changes have taken place in both NHS England and RHS Tuscany. In NHS England the outsourcing contract was first extended for two years and then indefinitely terminated, while in RHS Tuscany the three ESTAVs were merged into one organisation (named ESTAR) in 2014. Such developments have generated new challenges and opportunities, which deserve specific analysis. Future research could analyse the stages that followed the initial outsourcing to identify the relevant factors and outcomes.

Although NHS England and RHS Tuscany remain important cases, the results of this research cannot be generalised across public sector outsourcing. It would be helpful to replicate the analysis by adopting our adapted framework in other outsourcing experiences within international healthcare contexts. In this way a more consistent contribution to the debate among practitioners and academics regarding the benefits/challenges of joint procurement and logistics outsourcing can be developed. We hope this exploratory study motivates other researchers to pursue these avenues of research, and that it serves as a stepping stone to continue developing our understanding of public sector outsourcing, particularly in the healthcare sector, where performance outcomes can have dramatic effects on people’s lives.

In a healthcare context, the term single-payer refers to a system in which a single entity or public organisation collects funds and pays for health care on behalf of the population of a nation or region (Liu & Brook, 2017).