Abstract

Hand washing and maintaining social distance are the main measures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to avoid contracting COVID-19. Unfortunately, these measured do not prevent infection by inhalation of small droplets exhaled by an infected person that can travel distance of meters or tens of meters in the air and carry their viral content. Science explains the mechanisms of such transport and there is evidence that this is a significant route of infection in indoor environments. Despite this, no countries or authorities consider airborne spread of COVID-19 in their regulations to prevent infections transmission indoors. It is therefore extremely important, that the national authorities acknowledge the reality that the virus spreads through air, and recommend that adequate control measures be implemented to prevent further spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in particularly removal of the virus-laden droplets from indoor air by ventilation.

Keywords: Airborne transmission, Airborne infection spread, Infections transmission, Coronavirus, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 virus

The entire world is anxiously watching as COVID-19, a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, spreads from country to country, following modern travel routes. It was first reported to the WHO Country Office in China on 31 December 2019 (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen). After that, it inevitably crossed the country’s boundaries, and has become a global pandemic (WHO 2020b).

It could be said that compared with previous global epidemics or pandemics, humanity is much better equipped to control the new epidemic. The virus’s gene sequence was identified and made public and a testing method was developed within two weeks after its existence was announced (Zhu et al. 2020), launching the race to develop a protective vaccine (Yan et al. 2020). In addition, testing methods measuring the infection (using RT-PCR) and measuring the antibodies formed after being infected (using immunoassays) (Elfaitouri et al., 2005, Souf, 2016;9.). Real-time statistics on all aspects of the virus’s transmission are available online (Worldometers 2020). Countries have enacted emergency response procedures, and travel bans have been put in place (Tian et al. 2020), and lockdown procedures which limit the movement of people inside the administrative zones.

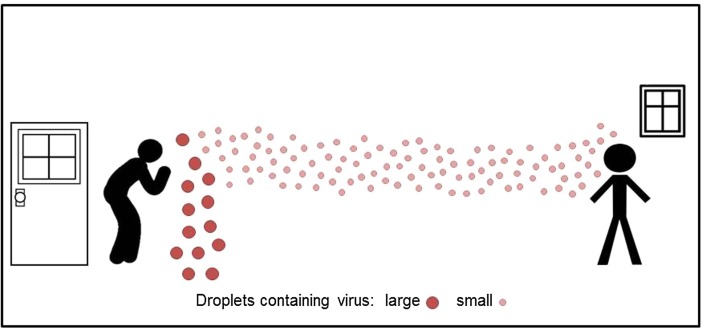

Unfortunately, the truth is that we have only a rudimentary knowledge of several aspects of infection spread, including on one critical aspect of the SARS-CoV-2 virus: how THIS virus transmits (Bourouiba, 2020, Brosseau, 2020). In general it is considered that viral respiratory infections spread by direct contact, such as touching an infected person or the surfaces and fomites that the person has either touched, or on which large virus-containing droplets expired by the person have landed (Morawska 2006), and there the virus can remain stable for days (van Doremalen et al. 2020). The droplets can also be deposited directly on a person in close proximity to the infected person. Therefore, frequent hand-washing and maintaining a distance of at least one meter (arm’s length) are considered the main precautions against contracting the infection (WHO 2020a). One transmission route that is mentioned only in passing, or not at all, is the transport of virus-laden particles in the air. Immediately after droplets are expired, the liquid content starts to evaporate, and some droplets become so small that transport by air current affects them more than gravitation. Such small droplets are free to travel in the air and carry their viral content meters and tens of meters from where they originated (e.g. Morawska et al. 2009), as graphically presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Larger droplets with viral content deposit close to the emission point (droplet transmission), while smaller can travel meters or tens of meters long distances in the air indoors (aerosol transmission).

Is it likely that the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads by air? Its predecessor, SARS-CoV-1, did spread in the air. This was reported in several studies and retrospectively explained the pathway of transmission in Hong Kong’s Prince of Wales Hospital (Li et al., 2005, Xiao et al., 2017;12., Yu et al., 2005), as well as in health care facilities in Toronto, Canada (Booth et al. 2005), and in aircraft (Olsen et al. 2003). These studies concluded that airborne transmission was the main transmission route in the indoor cases studied. Other examples of airborne transmission of viral infections include the spread of Norwalk-like virus between school children (Marks et al. 2003), and the transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets (Herfst et al. 2012). A World Health Organization (WHO 2009) review of the evidence stated that viral infectious diseases can be transmitted across distances relevant to indoor environments by aerosols (e.g. airborne infections), and can result in large clusters of infection in a short period. Considering the many similarities between the two SARS viruses and the evidence on virus transport in general, it is highly likely that the SARS-CoV-2 virus also spreads by air (Fineberg 2020). Experts in droplet dynamics and airflow in buildings agree on this (Lewis 2020). Therefore, all possible precautions against airborne transmission in indoor scenarios should be taken. Precautions include increased ventilation rate, using natural ventilation, avoiding air recirculation, avoiding staying in another person’s direct air flow, and minimizing the number of people sharing the same environment (Qian et al. 2018). Of significance is maximizing natural ventilation in buildings that are, or can be naturally ventilation and ensuring that the ventilation rate is sufficiently high. These precautions focus on indoor environment of public places, where the risk of infection is greatest, due to the possible buildup of the airborne virus-carrying droplets, the virus likely higher stability in indoor air, and a larger density of people. Public places include in the first instance heath care facilities: while in many hospitals care to provide adequate ventilation is a routine measure, this is not the case in all hospital; often not where new patients are admitted; nursing homes, etc. Shops, offices, schools, restaurants, cruise ships, and of course public transport, is where ventilation practices should reviewed, and ventilation maximized. Also, personal protective equipment (PPE), in particular masks and respirators should be recommended, to be used in public places where density of people is high and ventilation potentially inadequate, as they can protect against infection others (by infected individuals) and being infected (Huang and Morawska, 2019, Leung et al., 2020).

Precautions can be taken only when the national bodies responsible for the control of the outbreak acknowledge the significance of this route of transmission and recommend appropriate actions. Currently, this is not the case anywhere in the world. In China, where the outbreak started, the body overseeing the prevention and control of the epidemic (the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China) has issued a series of prevention and control guidelines. As of 12 March 2020, the guidelines have been updated six times (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202003/4856d5b0458141fa9f376853224d41d7.shtml), reflecting some change in the Commission’s perception of the mechanisms of the viral infection spread: from no mention of airborne transmission at all to an admission of the possibility of this route of transmission. However, the guidelines stopped short of accepting that this is in fact happening, and instead stated in the latest version (7 March 2020) that airborne transmission “has not been determined”. In Italy, which has emerged as one of the main hot spots in the world, the distance of 1 m between people is recommended in indoor “red zones”, but there is no mention of longer distance transport (Gazzetta Ufficiale 2020). The list of examples could go on. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Page last reviewed: October 30, 2018) takes a broader view of viral infection spread, stating that: “Airborne transmission over longer distances, such as from one patient room to another has not been documented and is thought not to occur”. At the time of writing, the daily increase in the number of cases of COVID-19 in the USA is fast (WHO et al., 2020).

It is difficult to explain why public health authorities marginalize the significance of airborne transmission of influenza or coronaviruses, but a possible reason is that it is difficult to directly detect the viruses traveling in the air. Immediately after expiration, the plume carrying the expired viral content is diluted, and as it travels in the air carried by the air flow. In the process, the concentration of the virus does not increase uniformly in the interior environment of the enclosed space, but it is elevated only in the flow (if there is adequate ventilation, which is normally the case in medical facilities or on aircraft) (Morawska 2006). Therefore, sampling for the presence of the virus requires knowledge of the air flow from the infected person, and a sufficiently long sampling period to collect enough copies of the viruses. Both these requirements present major challenges: microbiologists collecting viral samples are not normally experts in building flow dynamics, and practicality prevents long sampling times that would be adequate for the sensitivity of existing viral detection methods (Booth et al. 2005).

The fact that there are no simple methods for detecting the virus in the air does not mean that the viruses do not travel in the air. The above-mentioned retrospective modeling studies explained the transmission of SARS-CoV-1 in 2003 (Booth et al., 2005, Li et al., 2005, Olsen et al., 2003, Xiao et al., 2017;12., Yu et al., 2005). While we do not yet have all the required data in hand, including for example data on the patterns of infections, or specific indoor characteristics where the infections occurred, analysis of the initial pattern of COVID-19 spread in China reveals multiple cases of non-contact transmission, especially in areas outside Wuhan, such as those in Hunan and Tianjin. On numerous cruise ships where thousands of people onboard were infected, many of the infections occurred after the imposition of isolation that confined passengers for the majority of time to their cabins, and limited direct contact, and with hand hygiene carefully obeyed. Was it therefore the ventilation system that spread the airborne virus between the cabins one of the reasons for the infections? There are also hypothesis, that airborne transmission was at least partially responsible for a larger number of infections during a choir, where 45 out of 60 choir members were infected (Read 2020).

Despite the evidence and strong hypotheses, the world appears to be locked in the old way of thinking that only direct contact matters in viral infection spread. It is disconcerting that with all the experience and evidence currently available, when faced with a new viral outbreak of COVID-19, the authorities still fail to acknowledge the airborne pathway of transmission, although many experts in China and other countries have had experience in dealing with SARS.

We predict that this failure to immediately recognize and acknowledge the importance of airborne transmission and to take adequate actions against it will result in additional cases of infection in the coming weeks and months, which would not occur if these actions were taken. The air transmission issue should be taken seriously now, during the course of the epidemic. When the epidemic is over and retrospective data demonstrates the importance of airborne transmission it will be too late. Further, the lessons learnt now will prepare us better for when the next epidemic strikes.

To summarize, based on the trend in the increase of infections, and understanding the basic science of viral infection spread, we strongly believe that the virus is likely to be spreading through the air. If this is the case, it will take at least several months for this to be confirmed by science. This is valuable time lost that could be used to properly control the epidemic by the measures outlined above and prevent more infections and loss of life. Therefore, we plead that the international and national authorities acknowledge the reality that the virus spreads through air, and recommend that adequate control measures, as discussed above be implemented to prevent further spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Chantal Labbe for her assistance in literature search, drawing the figure and formatting the text. This work was supported by the Australia-China China for Air Quality Science and Management (ACC-AQSM). The authors confirm that no funding was received for this work and that Prof Morawska and Prof Cao both contributed equality to the paper. The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Handling Editor: Adrian Covaci

References

- Booth T.F., Kournikakis B., Bastien N., Ho J., Kobasa D., Stadnyk L. Detection of airborne severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus and environmental contamination in SARS outbreak units. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191:1472–1477. doi: 10.1086/429634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourouiba L. Turbulent Gas Clouds and Respiratory Pathogen Emissions: Potential Implications for Reducing Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosseau L. Commentary: COVID-19 transmission messages should hinge on science (16 March 2020) (http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/03/commentary-covid-19-transmission-messages-should-hinge-science). Center for Infectious Disease. Research and Policy (CIDRAP) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Prevention Strategies for Seasonal Influenza in Healthcare Settings, Guidelines and Recommendations. In: Prevention C.f.D.C.a., ed. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD); Page last reviewed: October 30, 2018.

- Elfaitouri A., Mohamed N., Fohlman J., Aspholm R., Frisk G., Friman G. Quantitative PCR-enhanced immunoassay for measurement of enteroviral immunoglobulin M antibody and diagnosis of aseptic meningitis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12:235–241. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.2.235-241.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg, H.V. Rapid Expert Consultation on the Possibility of Bioaerosol Spread of SARS-CoV-2 for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 1, 2020). In: The National Academies Press N.R.C., ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, National Research Council 2020; 2020.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale, D.R.I. IL PRESIDENTE DEL CONSIGLIO DEI MINISTRI. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana; 2020.

- Herfst S., Schrauwen E.J., Linster M., Chutinimitkul S., de Wit E., Munster V.J. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Wei, Morawska Lidia. Face masks could raise pollution risks. Nature. 2019;574(7776):29–30. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung N.H., Chu D.K., Shiu E.Y., Chan K.-H., McDevitt J.J., Hau B.J. Brief Communication: Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. Is the coronavirus airborne? Experts can’t agree (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00974-w) (Retrieved 6 April 2020) Nature News. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00974-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Huang X., Yu I., Wong T., Qian H. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Indoor Air. 2005;15:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P., Vipond I., Regan F., Wedgwood K., Fey R., Caul E. A school outbreak of Norwalk-like virus: evidence for airborne transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 2003;131:727–736. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803008689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L. Droplet fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air. 2006;16:335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L., Johnson G., Ristovski Z., Hargreaves M., Mengersen K., Corbett S. Size distribution and sites of origin of droplets expelled from the human respiratory tract during expiratory activities. J. Aerosol Sci. 2009;40:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen S.J., Chang H.-L., Cheung T.Y.-Y., Tang A.F.-Y., Fisk T.L., Ooi S.P.-L. Transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome on aircraft. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:2416–2422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Zheng X. Ventilation control for airborne transmission of human exhaled bio-aerosols in buildings. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018;10:S2295. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read R. A choir decided to go ahead with rehearsal. Now dozens of members have COVID-19 and two are dead. Los Angeles Times. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Souf S. Recent advances in diagnostic testing for viral infections. Bioscience Horizons: The International Journal of Student Research. 2016;9. [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Liu Y., Li Y., Wu C.-H., Chen B., Kraemer M.U. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Natural ventilation for infection control in health-care settings (https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/natural_ventilation/en/) ed^eds: World Health. Organization. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public). 2020a.

- WHO WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic (http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic) World Health Organisation. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- WHO; University, J.H. COVID19 Live Interactive Dashboard (https://datastudio.google.com/embed/reporting/f56febd8-5c42-4191-bcea-87a3396f4508/page/GQFJB?fbclid=IwAR0UiGnyFnjrrXwnj7Z7berl1EWWDTmivmDubq7NV8zSmXiyadk5gyM2drE). 2020.

- Worldometers. Coronavirus statistics (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/). 2020.

- Xiao S., Li Y., Wong T.-W., Hui D.S. Role of fomites in SARS transmission during the largest hospital outbreak in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE. 2017;12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xia, L.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of the 2019-nCoV by human ACE2. bioRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yu I.T., Wong T.W., Chiu Y.L., Lee N., Li Y. Temporal-spatial analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome among hospital inpatients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:1237–1243. doi: 10.1086/428735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]