Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. As the pandemic evolves rapidly, there are data emerging to suggest that pregnant women diagnosed as having coronavirus disease 2019 can have severe morbidities (up to 9%). This is in contrast to earlier data that showed good maternal and neonatal outcomes. Clinical manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 include features of acute respiratory illnesses. Typical radiologic findings consists of patchy infiltrates on chest radiograph and ground glass opacities on computed tomography scan of the chest. Patients who are pregnant may present with atypical features such as the absence of fever as well as leukocytosis. Confirmation of coronavirus disease 2019 is by reverse transcriptase-polymerized chain reaction from upper airway swabs. When the reverse transcriptase-polymerized chain reaction test result is negative in suspect cases, chest imaging should be considered. A pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 is at the greatest risk when she is in labor, especially if she is acutely ill. We present an algorithm of care for the acutely ill parturient and guidelines for the protection of the healthcare team who is caring for the patient. Key decisions are made based on the presence of maternal and/or fetal compromise, adequacy of maternal oxygenation (SpO2 >93%) and stability of maternal blood pressure. Although vertical transmission is unlikely, there must be measures in place to prevent neonatal infections. Routine birth processes such as delayed cord clamping and skin-to-skin bonding between mother and newborn need to be revised. Considerations can be made to allow the use of screened donated breast milk from mothers who are free of coronavirus disease 2019. We present management strategies derived from best available evidence to provide guidance in caring for the high-risk and acutely ill parturient. These include protection of the healthcare workers caring for the coronavirus disease 2019 gravida, establishing a diagnosis in symptomatic cases, deciding between reverse transcriptase-polymerized chain reaction and chest imaging, and management of the unwell parturient.

Key words: ACE2, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acutely ill, ARDS, coronavirus, coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, maternal morbidity, MERS, obstetric management, pandemic, pregnancy, SARS-CoV-2, SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome, vertical transmission, virus

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 are the largest group of RNA viruses.1 COVID-19 has now been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The elderly are at greatest risk.2 Current evidence suggests that neither are pregnant women at a greater risk of COVID-19 than other adults,3 nor is the condition thought to be more severe in them.4 A case series of 9 pregnant women at term and late preterm (36 weeks and above) reported good maternal and fetal outcomes.5 However, all these cases had short time intervals between the diagnosis of COVID-19 and cesarean deliveries, and the true impact of the disease on pregnant women should not be extrapolated from this descriptive study. Moreover, when a larger cohort of 147 pregnant patients was evaluated (WHO-China joint mission report),6 up to 8% of the cohort were either severely ill (respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min, oxygen saturation ≤93% at rest, or PaO2/FiO2 <300 mm Hg) or 1% critically ill (respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, shock, or other organ failure that requires intensive care). This rate of severe illness in pregnancy was less than that observed during the influenza (H1N1) pandemic.6 These statistics came from a country that is now recognized globally to be dealing admirably with the COVID-19 outbreak, having gained experience from the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. It is uncertain whether other health systems would experience severe maternal morbidity below 10% or instead severe illnesses in pregnant women closer to 25% as observed in other coronavirus infections such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and SARS.1 , 7

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to have 85% similarity with SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Both the SARS and MERS epidemics had significant adverse effects on pregnant women including preterm deliveries, stillbirths, respiratory complications, and maternal mortality.1 Preexisting physiological factors such as basal atelectasis from gravid uterus, lower lung reserves (reduced functional residual capacity), and increased oxygen consumption (30%)8 predispose the parturient to poor outcomes during respiratory illnesses, such as coronavirus pneumonia. However, there is reasonably good evidence to suggest that vertical transmission from the pregnant patient to the fetus is unlikely.2 , 9 Recommendations are in place for managing suspected or confirmed pregnant patients with COVID-19, ensuring the safety of their neonates, other parturients in the delivery suite, and healthcare workers caring for them.3 , 10 , 11

Disease transmission and case fatality rate (2.3%)12 are known to be lower in health systems with better systematic pandemic preparedness strategies13 and experience in managing coronavirus outbreaks. As of March 25, 2020, Singapore has hospitalized 631 COVID-19 cases confirmed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), 3 of which were pregnant. Of these 631 patients, 160 fully recovered from the infection and were discharged from hospital. There were 2 mortalities from complications owing to COVID-19, 1 of which was an imported patient who was ill before coming to Singapore and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) upon arrival.14 Singapore was taken by surprise during the 2003 SARS epidemic, but it has since built capacity and capability within the country to manage global infectious disease emergencies with standard protocols for nongravid and pregnant patients.

Clinical presentation

COVID-19 can present with a spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from mild signs and symptoms,15 such as fever, cough, sore throat, myalgia, and malaise, to severe illness, such as pneumonia with or without acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),2 renal failure, and multiorgan dysfunction that may require immediate advanced critical care support. Clinical presentations in pregnant patients with COVID-19 could be atypical with normal temperature (56%) and leukocytosis.16

Clinical virology

The largest report to date on COVID-19 from China revealed 1% asymptomatic of 72,134 cases. Of the 44,672 cases confirmed by RT-PCR, 8% were aged between 20 and 29 years whereas 87% between 30 and 79 years. There was no further stratification in the 30 to 79 years age group to represent the reproductive age group 30 to 45 years. Of the 44,415 cases with data on clinical severity, 81% were classified as mild, 14% severe (dyspnea, tachypnea, or oxygen saturation ≤93%), and 5% critical (respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiorgan failure).12 Overall, case fatality was 2.3%, with 8% of patients in the age group of 70 to 79 years, 14.8% in 80 years and older, and 49% among critically ill.12 More detailed clinical information from 1099 patients revealed that fever was present in 43.8% on admission but developed in 88.7% during hospitalization. Cough was present in 67.8%, but sputum production was observed only in 33.7%, nasal congestion 4.8%, sore throat 13.9%, and diarrhea 3.8%.17 The median time from illness onset to dyspnea was 8 days, to ARDS 9 days, and ICU admission 10.5 days.15 Compared with non-ICU patients, ICU patients with COVID-19 were older with comorbidities and had higher temperature; more dyspnea and tachypnea; more leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and lymphopenia; and higher alanine and aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, creatinine, procalcitonin, troponin, D-dimer, and lactate dehydrogenase.15 , 16 , 18

Diagnosing coronavirus disease 2019

Confirmation of the disease is done using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as real-time RT-PCR.13 Average RT-PCR testing needs up to 2 hours, but it takes between 6 and 10 hours for completion, or even longer when batch testing is done by laboratories.19

Chest imaging

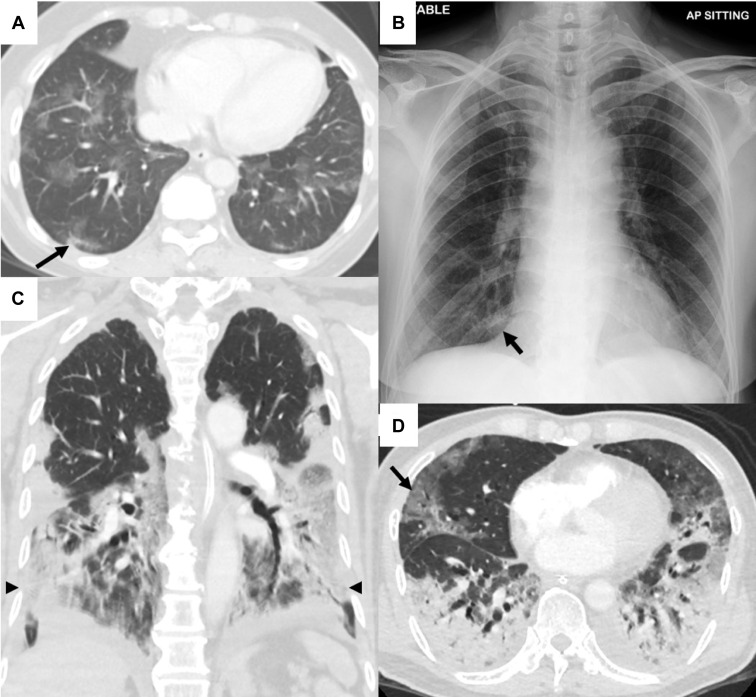

Imaging of the lungs is important in assessing the extent of COVID-19 pneumonia and in follow-up. Evidence on ultrasonographic imaging of the lung in patients with COVID-19 is evolving. In up to 85% of patients, abnormalities are found on imaging during the acute phase.20 Radiologic features of COVID-19 include patchy infiltrates on chest x-ray (CXR) and ground glass opacities (GGOs) on chest computed tomography (CT) scan.21 CXRs can be rapidly performed at bedside but may have reduced sensitivity in the early stages of infection. Chest CT scan is more sensitive than CXR (Figure 1A and 1B), but its widespread use is limited by availability, the practical but no less important consideration of the need for terminal cleaning to prevent nosocomial transmission, and acceptance by pregnant women. On chest CT, multilobar GGOs are most commonly seen, whereas lower lobe consolidation is more frequently observed in patients with severe and prolonged disease (Figure 1C and 1D).20 Given its relatively untested specificity, its use as a first-line diagnostic tool has been discouraged by the American College of Radiology.22

Figure 1.

Chest imaging in patients with COVID-19

Imaging of 2 patients with COVID-19. A, Contrast-enhanced CT of 1 patient in the axial plane across the lower lobes of the lungs shows patchy GGO in a lobular distribution. Early changes of consolidation are present in the posterior segment of the right lower lobe (arrow). B, Corresponding chest radiograph does not reveal significant abnormality other than a small focus of consolidation in the medial right lower zone (arrow), which would have been easily missed owing to projection adjacent to the right cardiophrenic angle and overlapping rib shadow. C and D, CT pulmonary angiogram of a different patient with severe pneumonia in the axial and coronal planes showing extensive multilobar GGO (arrows) with areas of confluent consolidation (arrowheads) mostly distributed in the posterior and basal regions of the lower lobes. No pulmonary embolism was detected. These findings are not specific to COVID-19 and may be seen in other viral and atypical pneumonias.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; GGO, ground glass opacity.

Ashokka. Care of the pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020.

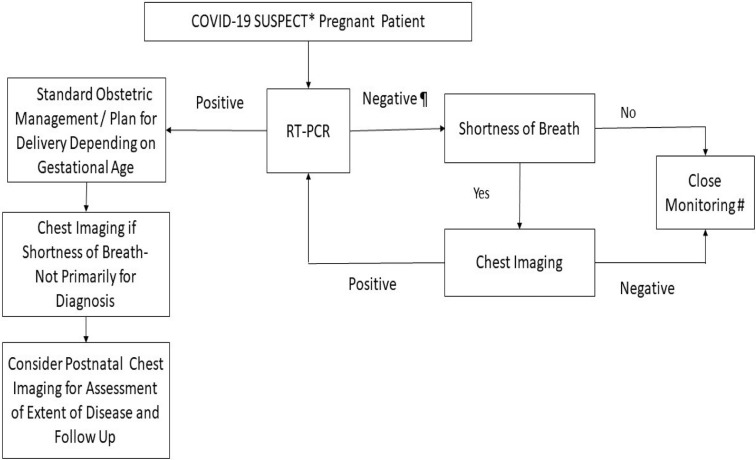

In an epidemic setting where there is very high pretest probability of COVID-19 infection, a positive result on chest CT scan may precede RT-PCR and chest CT may have higher sensitivity for diagnosis.23 In a case series of 15 pregnant patients with COVID-19 who were exposed to ionizing radiation between 2.3 and 5.8 mGy, all were found to have CT findings of mild disease, which did not worsen with pregnancy.22 In some circumstances when an earlier diagnosis of COVID-19 would alter the management of an obstetric patient, particularly if the patient is in respiratory distress raising concerns about significant pneumonia or concomitant pathology (eg, pulmonary embolism), CXR, and thereafter chest CT if needed, could be considered. A diagnostic workflow detailing the application of RT-PCR and chest imaging in the assessment of suspected patients with COVID-19 is described (Figure 2 ). In such instances, abdominal lead shielding may be applied to reassure patients of the minute risks of scatter radiation to the fetus.24 , 25

Figure 2.

Suspected pregnant patient with COVID-19 diagnostic workflow

∗A suspected case of COVID-19 is one who presents with an acute respiratory illness of any degree of severity who, within 14 days before onset of illness, had traveled to any listed countries requiring heightened vigilance or had prolonged close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient. ¶ Negative RT-PCR tested in 2 consecutive days, at least 24 hours apart. ∗∗Close monitoring includes social and physical distancing, body temperature monitoring, and assessment of symptoms of acute respiratory illness. Chest imaging includes chest x-ray, chest CT, and lung ultrasound.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerized chain reaction.

Ashokka. Care of the pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020.

Differential diagnosis

COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory illness. As our understanding of the diagnostic imaging features of COVID-19 evolves, significant overlap with other viral and atypical pneumonias has been increasingly reported. On CXR, COVID-19 pneumonia often presents with multifocal, bilateral airspace opacification.2 This distinguishes it from the more common unifocal involvement noted in SARS,26 but not in MERS.27 When imaged by CT, the distribution seen in COVID-19 is similar to that noted in other viral and coronaviral20 pneumonias, such as influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus.28 , 29 Even the multifocal GGOs, described in more than 80% of COVID-19 pneumonias,30 are common features of atypical (eg, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and opportunistic (eg, Pneumocystis jirovecii) pneumonias.31 , 32 As with other viral pneumonias, lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions are uncommon associated findings.30 In the later stages of COVID-19, confluent consolidation and interstitial thickening become more pronounced, with up to 20% patients developing features of ARDS.18 , 21 Given the significant overlap of imaging findings with other acute viral respiratory infections, imaging alone is unlikely to supplant the role of RT-PCR for the primary diagnosis of COVID-19.

Minimizing disease transmission

Person-to-person transmission is now known to occur via fomites, droplets through close proximity aerosols,33 , 34 and prolonged close contact within a 2-m perimeter.13A study revealed that patients can continue to shed the virus as evidenced by positive RT-PCR results for up to 13 days after disease resolution. Stool sample remained positive in 50% of recovered patients.35 Coronavirus epidemics in the past are known to have occurred with aerosolization from flushing of toilets.1

The spread of infection has been reported from asymptomatic patients, thereby rendering early detection and disease containment difficult.36 There is a possibility of viral dissemination when a patient is forcefully exhaling when in pain during active labor.25 Hence it is prudent to consider early epidural analgesia for optimal pain control, and unmedicated natural labor should be discouraged. In addition, all healthcare staff attending to women in active labor need to don full personal protective equipment (PPE).

Infection control

In a simulated experiment where aerosols were generated using a 3-jet Collison nebulizer and fed into a Goldberg drum, SARS-CoV-2 could survive on plastic and stainless steel surfaces for 72 hours, cardboard 24 hours, and copper 4 hours. The median half-life of the virus in this simulated aerosol was 2.7 hours (95% confidence interval, 1.65–7.24 hours).34 In contrast, in a real-world experiment conducted in Singapore, 3 patients in different rooms had surface environmental samples taken at multiple sites, which revealed that bleach disinfection was highly effective in 2 rooms and fomite contamination was common in the third room. Notably, air, PPE, anteroom, and corridor samples were negative.35 In addition, a case report of emergency intubation in an unsuspected patient subsequently found to have a positive test result for COVID-19 showed that no healthcare workers wearing surgical or N95 masks were infected.36 In summary, current recommendations for hand hygiene, eye protection, N95 mask, splash-resistant gown, and gloves should be sufficient.

Managing patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor

A pregnant woman presenting to the delivery suite or emergency department needs to be triaged based on the presence of maternal and/or fetal compromise (Figure 2). When there is imminent risk, emergency cesarean delivery must be performed. When there are other maternal and fetal conditions requiring early operative delivery, a coordinated team response is initiated for assessment and optimization of maternal oxygenation and infection control measures. Cesarean delivery is advised for maternal indications, such as worsening condition of the mother related to COVID-19 and fulminant preeclampsia, or fetal indications, such as nonreassuring fetal status. When an operative delivery is not planned, pregnant mothers need to be admitted into the delivery suite for detailed assessment, labor pain management, stratification of infection control precautions, and plans for safe delivery of the fetus. In the presence of COVID-19, the threshold for cesarean delivery should be lower than usual so that infection control procedures can be more readily adhered to and disease transmission minimized.

Safe and optimal care of the parturient in the peripartum period requires a multidisciplinary team approach.37 The healthcare professionals who provide this coordinated care include obstetricians, neonatologists, anesthesiologists, midwives, and support services at the delivery suite. Here, we highlight the acute care perspectives of the parturient, summarize existing evidence, and propose an algorithmic approach for the management of the acutely ill parturient.

Anesthesia in emergency cesareans for pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019

An emergency cesarean delivery (30-min decision-to-incision interval) mandates a systematic plan and preparedness for minimizing cross-contaminations.38 Although emergency cesarean delivery needs to be performed as soon as possible, there are instances where the decision to go for urgent cesarean delivery has some lead time. The possibilities of suspected patients with COVID-19 requiring imminent operative deliveries have to be communicated to the operating room team so that they could be conducted in negative-pressure operating rooms.38

When a COVID-19 parturient with desaturation (oxygen saturation decreases to ≤93%) presents for emergency cesarean delivery, general anesthesia needs to be administered, which is done with rapid sequence induction (RSI) and tracheal intubation with a cuffed tube. The airway team should don full PPE and powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). The presence of systemic complications of COVID-19 such as renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation might warrant the use of invasive monitoring (intra-arterial blood pressure and central venous pressure).

When the parturient’s oxygen saturation is adequate (94% and above), 6 , 10 regional anesthesia with epidural top-up or single-shot subarachnoid blockade needs to be actively considered instead of general anesthesia10 to minimize aerosolization and cross-infection during airway management. Where there is a working epidural catheter in place for continuous labor analgesia, administering a top-up with potent local anesthetics (eg, 10–15 mL of 1.5% lignocaine, alkalinized with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate) achieves surgical anesthetic plane with a rapid onset of 3.5 minutes. Rapid sequence spinal anesthesia39 is described for emergency cesarean deliveries, wherein patients are placed in a left lateral position with supplemental oxygen, and a single-shot subarachnoid blockade is administered by the most experienced prescrubbed anesthetist. The time required for surgical readiness is comparable with that for general anesthesia, and neonatal outcomes are better.40

Extubation after general anesthesia should be performed with the same precautions as with intubation.41 Patients tend be more agitated during emergence from anesthesia and extubation, which could result in increased likelihood of viral dissemination from coughing as compared with the intubation process.42 During RSI and intubation, patients are anesthetized, hence paralyzed and unable to cough. It is imperative that all operating room personnel wear full PPE until patients are safely extubated and transferred out of the operating room.38 , 41

The disposition for patients with COVID-19 after unplanned cesarean delivery should be decided at the earliest instance. Transferring these patients to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) might compromise and cross-contaminate other postoperative patients. Provisions should be made for suspected and confirmed patients to recover in the operating rooms where cesarean deliveries were performed. Patients should subsequently be transferred directly to isolation wards after recovery.

The acutely ill parturient

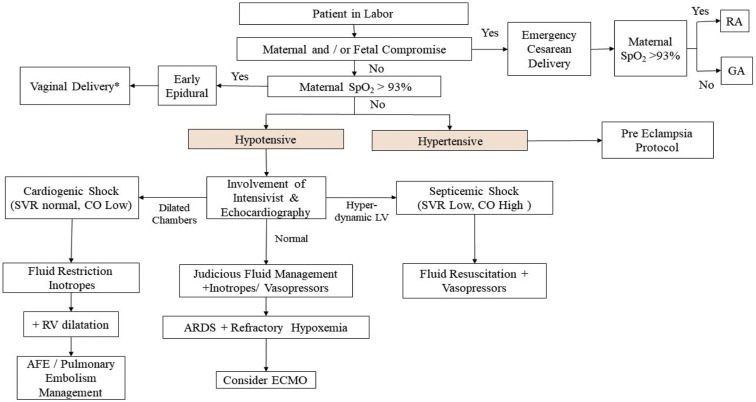

When a parturient desaturates, there are multiple etiopathologies: infective (pneumonia with or without COVID-19), inflammatory (systemic inflammatory response syndrome), cardiogenic (peripartum cardiomyopathy, viral myocarditis), and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema (hypertensive and nonhypertensive pulmonary edema).43 A stepwise approach for systematic management of the acutely ill parturient is detailed (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Stepwise approach for the care of acutely ill parturient

At all times, maternal and fetal compromise has to be assessed and acted upon as per standard intrapartum obstetric management. ∗Exclude obstetric contraindication to vaginal delivery.

AFE, amniotic fluid embolism; ARDS, adult respiratory distress syndrome; CO, cardiac output measured by noninvasive pulse contour methodology from intra-arterial waveform analysis; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GA, general anesthesia; LV, left ventricle; RA, regional anesthesia; RV, right ventricle; SpO2, percentage saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

Ashokka. Care of the pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020.

If there is absence of maternal and/or fetal compromise, and emergency cesarean delivery is not indicated, further plans for management of patients are then made (Figure 3). When parturients are acutely ill, it may be challenging to differentiate etiologies based on the presence of tachypnea and tachycardia. The percentage saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen (SpO2) is a noninvasive continuous monitoring that provides real-time information on peripheral oxygen saturation. It also provides indirect information on adequacy of pulmonary gas exchange, cardiac function, and intravascular volume status. There is a correlation between oxygenation measured by SpO2 and invasive arterial blood gas. An arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) of less than 60 mm Hg corresponds to SpO2 of less than 90%.44 Delivery units need to be equipped with and use continuous SpO2 monitoring. Disposable low-cost SpO2 finger probes are commercially available and need to be considered when multiparameter monitoring is not available. Moreover, knowing the PaO2/FiO2 ratio is useful in predicting the degree of lung compromise.6

When SpO2 has decreased to less than 94%, rapid clinical decisions must be made in the context of COVID-19. Hypotensive patients with low SpO2 must be prioritized and systematically managed at the earliest, taking into consideration cardiac, noncardiac, and septic causes.

Bedside transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is a practical and swift method for the assessment of hypotension.45 A poorly contractile left ventricle signifies cardiac pump failure. In this case, fluids should be restricted and the use of inotropes should be considered. Hyperdynamic cardiac activity as evidenced by “kissing” ventricular walls is suggestive of distributive shock such as in sepsis. This requires fluid resuscitation and the use of vasopressors. To assess the patient’s intravascular volume status, TTE probe can also be used to image the inferior vena cava (IVC). Avoidance of fluid mismanagement is crucial; fluid loading in cardiomyopathy can precipitate congestive cardiac failure that worsens lung oxygenation.

Cardiovascular causes of desaturation in COVID-19 include systolic failure from viral myocarditis, congestive cardiac failure, and pulmonary edema. The SARS-CoV-2 surface glycoprotein interacts with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) of the respiratory epithelial cells of the host. The predominant pulmonary features are from the ACE2 expression in type 2 alveolar cells. Elevated blood pressure is known to occur from interaction between the virus and ACE2.46 This might result in misdirected management toward preeclampsia, whereas hypertension is a cardiovascular manifestation of COVID-19. Myocardial injury as evidenced by raised troponin levels is a feature of cytokine storms,47 that is, high concentrations of granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (GCSFs), interferon gamma–induced protein 10 (IP10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP1α), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).15 Cytokine storms are known to be associated with disease severity and ICU admissions.17 , 47

Morbid manifestations of COVID-19 such as severe pneumonia, ARDS, and multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) require advanced ventilatory and circulatory support.12 When patients present with hypoxemia, it is important to differentiate between failure of gas exchange in the lungs and cardiogenic causes of pump failure.43 Pulmonary causes of desaturation from pneumonia, acute lung injury, and ARDS are more difficult to manage because they may require prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Pressurized air enriched with oxygen is needed for improving oxygenation in acutely ill patients with respiratory compromise. It can be administered via nasal masks, full face masks, and helmets. Simulation-based experiments have shown the effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with tight fitting oronasal mask and noninvasive ventilation with well-sealed helmets, posing negligible risk of exhaled air dispersion.48 Similar studies have shown that exhaled air dispersion distance during application of high-flow nasal cannula is shorter than CPAP that tends to be applied less tightly.49 Hence, centers that are experienced and equipped with negative-pressure rooms could consider noninvasive ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula, and CPAP, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when facilities with full mechanical ventilatory support are overwhelmed.

Where the patient’s oxygen saturation is refractory to mechanical ventilatory support, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)50 should be considered. Initiating ECMO in a pregnant patient needs special considerations. Although anticoagulation is needed to prevent clotting in the extracorporeal circulation, this complicates hemostasis at the placental site if ECMO is used in the peripartum period. ECMO setup requires multidisciplinary planning and is best done in tertiary institutions. Maternal and child health facilities without cardiac surgical ICUs might not be able to acquire this service. The transfer of critically ill patients to tertiary institutions needs meticulous planning.

Drugs and evolving therapy for coronavirus disease 2019

Antiviral treatment

Much of the early information on COVID-19 treatment was derived from experience in SARS. Data on the use of antiviral therapy for COVID-19 in pregnancy are limited.51 In SARS, ribavirin and corticosteroid showed possible harm with inconclusive clinical data, whereas studies on convalescent plasma, interferon, and lopinavir were inconclusive.51 In the first randomized controlled trial on COVID-19 treatment, 400-mg/100-mg lopinavir-ritonavir twice daily was found to be similar to the standard of care in time to clinical improvement, mortality, and viral shedding.52 This may be due to differences in viral proteases between HIV and coronavirus.53 An in vitro study on repurposed drugs for COVID-19 reported effective concentration 50 (EC50) of 0.77 for remdesivir, 1.13 for chloroquine, 61.88 for favipiravir, and 109.50 for ribavirin.54 EC50 for hydroxychloroquine was significantly higher than chloroquine.55 In a French nonrandomized study,56 26 patients received 200-mg hydroxychloroquine thrice daily for 10 days, 6 of whom also received azithromycin 500 mg on day 1 and 250 mg daily for the next 4 days. Compared with 16 untreated patients, there was significant reduction in viral load at day 6 and shorter duration of viral shedding, with additive effect from azithromycin. In a Chinese nonrandomized study,57 35 patients were treated with favipiravir 1600 mg twice daily on day 1 and 600 mg twice daily from days 2 to 14 and 45 patients were treated with lopinavir-ritonavir; patients in both arms received aerosolized interferon alfa (IFN-α) 5 million units twice daily. Compared with control, favipiravir was associated with shorter viral shedding and faster radiologic improvement.

The delivery suite and considerations for minimizing cross-contamination

Enhanced infection control precautions include restrictions on the number of personnel in the delivery suite to minimize cross-contaminations, movements between care locations, and the number of external visitors and care providers.58 The care for the parturient should be specialist led. When there is a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19, delivery processes such as water birth need to be revised to limit the potential spread of infection. In addition, strict adherence to policies for segregations of teams deployed in delivery suite, general ward, procedure rooms, and outpatient units is recommended.59 The workflow on peripartum management of COVID-19 women is detailed in the Appendix.

Labor analgesia can be planned well in advance such that when patients are in early labor, they receive good pain control through initiation of epidural analgesia.10 This reduces chances of viral disseminations during hyperventilation when the parturient is in pain, thereby reducing the risk of cross-contamination between staff and patients.25 Inhaled entonox is not recommended10 because it could increase the risk of viral dissemination through aerosols, especially when the parturient is not able to achieve tight uninterrupted mask seal throughout the duration of labor.42 , 48 , 49

Care of newborn of COVID-19 mothers

Current evidence shows that there is no vertical transmission during pregnancy.2 , 9 However, babies born to mothers with COVID-19 can acquire the infection after delivery. Practices such as delayed cord clamping and skin-to-skin bonding between mothers and newborns are not recommended. The evidence regarding the safety of breastfeeding is still limited.2 , 25 , 59 Considerations can be made to allow the use of screened donated breast milk from COVID-19–free mothers.

The process of segregation is simple when the newborn is healthy. However, the process becomes more complicated when there is perinatal asphyxia or need for ventilatory support. Finding an isolation unit for the newborn who requires continuous monitoring is a challenge. Specific care locations for newborns of mothers with COVID-19 have to be designated in advance; care teams need to be trained on workflow and infection control measures.

Maternal collapse and perimortem delivery

In the unfortunate event of maternal collapse, it can be challenging to regulate and adapt all aspects of infection prevention. The delivery suite is overwhelmed when many personnel simultaneously attempt to resuscitate the collapsed patient, perform a perimortem cesarean delivery, and resuscitate the newborn. The resuscitation team should don full PPE. The most common occurrence of serious cross-infections to healthcare workers during outbreaks was in crisis situations when first responders were not wearing the recommended PPE.1

Summary

The number of cases of COVID-19 continues to rise exponentially in many parts of the world. Pregnant women at all gestational ages are counted among this increase, and the gravida in labor and the acutely ill parturient are at the greatest risk. When the woman in labor needs an emergency cesarean delivery or the plan is to achieve a vaginal birth, she and the health support team face many unique challenges. We present here the best evidence available to address many of these challenges, from making the diagnosis in symptomatic cases to the debate between nucleic acid testing and chest imaging and to the management of ill patients in labor. There is reasonably good evidence that vertical transmission is unlikely, and efforts must be taken to prevent infection of the neonate. Given the limited knowledge about this novel coronavirus, which has both similarities and differences to SARS and MERS, the management strategies provided here are a general guide based upon current available evidence and may change as we continue to learn more about the effect of COVID-19 in pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the pediatric infectious diseases inputs from Dr Chan Si Min, Pediatrics, National University Hospital Singapore. The authors thank Dr Pradip Dashraath and Dr Wong Jing Lin Jeslyn, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National University Hospital Singapore, for their inputs during the initial discussion about the direction of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Peripartum management of women with COVID-19

Glossary.

ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (the functional receptor of SARS-CoV-2)

AFE: amniotic fluid embolism

ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome

CO: cardiac output measured by noninvasive pulse contour methodology from intra-arterial waveform analysis

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019 (previously called 2019 novel coronavirus [2019-nCoV])

CT: computed tomography

CXR: chest X-ray

ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

EC50: effective concentration 50 (concentration of a drug that gives half maximal response)

Emergency cesarean delivery: operative delivery that is to be conducted within 30 minutes after the decision is made for the surgery

FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen

Functional residual capacity: volume of air in the lungs at the end of expiration; it is the sum of residual volume and end expiratory volume

GA: general anesthesia

GCSF: granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

GGO: ground glass opacity

ICU: intensive care unit

IFN-α: interferon alfa

IP10: interferon gamma–induced protein 10

IVC: inferior vena cava

LV: left ventricle

MCP1: monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

MIP1α: macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alfa

MERS: Middle East respiratory syndrome

MERS-CoV: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

MODS: multiorgan dysfunction syndrome

NAAT: nucleic acid amplification test

Negative-pressure room: room that maintains a lower air pressure inside the treatment area than that of the surrounding environment

NIV: noninvasive ventilation

N95 mask: respiratory protective device that removes at least 95% of very small (0.3 micron) test particles; the American equivalent of an FFP2 respirator

PACU: postanesthesia care unit

PaO2: arterial partial pressure of oxygen

PAPR: powered air-purifying respirator

PaO2/FiO2 ratio: ratio between arterial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)

PPE: personal protective equipment

RA: regional anesthesia

RSI: rapid sequence induction

RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

RV: right ventricle

SARS: severe acute respiratory syndrome

SARS-CoV: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus—virus that causes SARS

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 virus—virus that causes COVID-19

SpO2: percentage saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen

Suspect case of COVID-19: a patient who presents with an acute respiratory illness of any degree of severity who, within 14 days before onset of illness had traveled to any listed countries requiring heightened vigilance, or had prolonged close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient

SVR: systemic vascular resistance

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha

TTE: transthoracic echocardiography

WHO: World Health Organization

| Antenatal management |

|

Patient will be admitted to isolation ward with negative-pressure room. Teams to be activated upon admission to isolation ward

|

| If steroids administration is considered, the decision will be made following joint discussion by obstetrics, neonatology, and infectious disease teams. |

Items to be discussed and completed in the antenatal ward:

|

| Intrapartum management |

|

Once labor starts, patient is to be transferred from the isolation ward to the isolation room in the delivery suite. If the isolation room in the delivery suite is not available, the patient will be transferred to the medical intensive care unit for delivery. Teams to activate once patient arrives in delivery suite:

|

Clinical samples to be collected at the time of delivery (perinatal) – full PPE for sample collection. This may vary depending on clinical needs and facilities available at each center.

|

| Postpartum management |

After delivery:

|

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EDTA, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; ICU, intensive care unit; PAPR, powered air-purifying respirator; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Ashokka. Care of the pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020.

References

- 1.Schwartz D.A., Graham A.L. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses. 2020;12:194. doi: 10.3390/v12020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen S.A., Smulian J.C., Lednicky J.A., Wen T.S., Jamieson D.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao J. What are the risks of COVID-19 infection in pregnant women? Lancet. 2020;395:760–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf Available at:

- 7.Wong S.F., Chow K.M., Leung T.N., et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan E.K., Tan E.L. Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27:791–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H., Wang L., Fang C., et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:51–60. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/coronavirus-pregnancy/covid-19-virus-infection-and-pregnancy/ Available at:

- 11.Poon L.C., Yang H., Lee J.C.S., et al. ISUOG interim guidance on 2019 novel coronavirus infection during pregnancy and puerperium: information for healthcare professionals. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/uog.22013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong J.E.L., Leo Y.S., Tan C.C. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health Singapore. Passing of two patients with COVID-19 infection. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/passing-of-two-patients-with-covid-19-infection Available at:

- 15.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Liu F., Li J., Zhang T., Wang D., Lan W. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: focus on pregnant women and children. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National University of Singapore, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health SSHSPH COVID-19 science reports: diagnostics. https://sph.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/COVID-19-Science-Report-Diagnostics-23-Mar.pdf Available at:

- 20.Hosseiny M., Kooraki S., Gholamrezanezhad A., Reddy S., Myers L. Radiology perspective of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): lessons from severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020 doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22969. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu D., Li L., Wu X., et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a preliminary analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020 doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23072. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Radiology . American College of Radiology; Reston, VA: 2013. American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation. ACR-SPR practice parameter for imaging pregnant or potentially pregnant adolescents and women with ionizing radiation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H., Wang C., Poon L.C. Novel coronavirus infection and pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55:435–437. doi: 10.1002/uog.22006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong K.T., Antonio G.E., Hui D.S., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic appearances and pattern of progression in 138 patients. Radiology. 2003;228:401–406. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282030593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das K.M., Lee E.Y., Al Jawder S.E., et al. Acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: temporal lung changes observed on the chest radiographs of 55 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W267–W274. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller W.T., Jr., Mickus T.J., Barbosa E., Jr., Mullin C., Van Deerlin V.M., Shiley K.T. CT of viral lower respiratory tract infections in adults: comparison among viral organisms and between viral and bacterial infections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1088–1095. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchiori E., Zanetti G., D’Ippolito G., et al. Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viral infection: thoracic findings on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W723–W728. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salehi S., Abedi A., Balakrishnan S., Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020 doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koo H.J., Lim S., Choe J., Choi S.H., Sung H., Do K.H. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics. 2018;38:719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franquet T. Imaging of pulmonary viral pneumonia. Radiology. 2011;260:18–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11092149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., et al. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng K., Poon B.H., Kiat Puar T.H., et al. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. Kilpatrick S.J., Papile L.A., Macones G.A. 8th edition. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove, IL: 2017. Guidelines for perinatal care. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ti L.K., Ang L.S., Foong T.W., Ng B.S.W. What we do when a COVID-19 patient needs an operation: operating room preparation and guidance. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01617-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinsella S.M., Girgirah K., Scrutton M.J. Rapid sequence spinal anaesthesia for category-1 urgency caesarean section: a case series. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:664–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim G., Facco F.L., Nathan N., Waters J.H., Wong C.A., Eltzschig H.K. A review of the impact of obstetric anesthesia on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:192–215. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wax R.S., Christian M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan M.T.V., Chow B.K., Lo T., et al. Exhaled air dispersion during bag-mask ventilation and sputum suctioning - implications for infection control. Sci Rep. 2018;8:198. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennis A.T., Solnordal C.B. Acute pulmonary oedema in pregnant women. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:646–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeserson E., Goodgame B., Hess J.D., et al. Correlation of venous blood gas and pulse oximetry with arterial blood gas in the undifferentiated critically ill patient. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33:176–181. doi: 10.1177/0885066616652597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dennis A.T. Transthoracic echocardiography in obstetric anaesthesia and obstetric critical illness. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2011;20:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong C.K., Lam C.W., Wu A.K., et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui D.S., Chow B.K., Lo T., et al. Exhaled air dispersion during noninvasive ventilation via helmets and a total facemask. Chest. 2015;147:1336–1343. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hui D.S., Chow B.K., Lo T., et al. Exhaled air dispersion during high-flow nasal cannula therapy versus CPAP via different masks. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1802339. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02339-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLaren G., Fisher D., Brodie D. Preparing for the most critically ill patients with COVID-19: the potential role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2342. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dashraath P., Jing Lin Jeslyn W., Mei Xian Karen L., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li G., De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 58.Cai Q., Yang M., Liu D., et al. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chua M.S.Q., Lee J.C.S., Sulaiman S., Tan H.K. From the frontlines of COVID-19—how prepared are we as obstetricians: a commentary. BJOG. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16192. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]