To the Editor:

Although coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is mainly characterised by respiratory symptoms that can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),1 , 2 abnormalities in liver enzymes have been reported during severe infections.3 Many liver centres worldwide have faced the challenge of managing patients with liver diseases during this pandemic3 and particular concerns have been raised about immunocompromised patients. This is mainly based on previous data on the higher risk of severe respiratory viral infections in patients treated with immunosuppressive medications.4 , 5 However, preliminary experience from Bergamo, Lombardy, suggests that immunosuppressed patients are not at increased risk during COVID-19;6 while Chinese data from the epicentre of the infection show that patients with chronic liver disease were only a minority among those infected with COVID-19.2

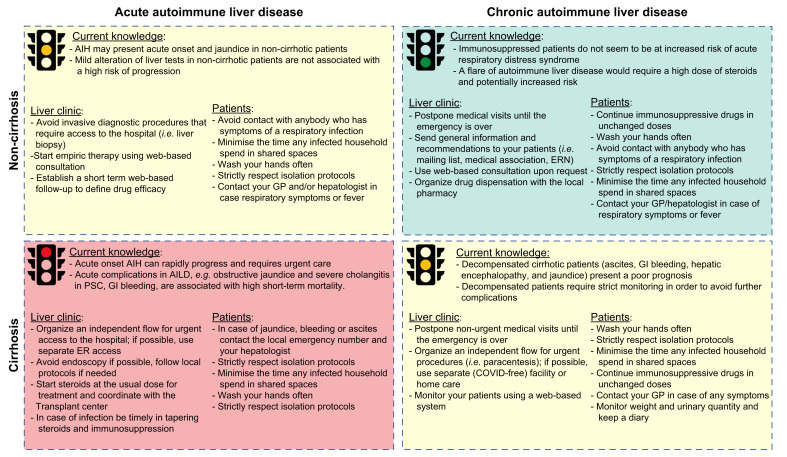

One area of major concern are patients with autoimmune liver diseases (AILDs), particularly those with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) or cirrhosis receiving immunosuppressive therapy, due to the lack of evidence-based treatment recommendations. This may lead to an empirical reduction of immunosuppressive agents, particularly antimetabolites, which is probably not justified. Herein, we present a brief description of the management protocol developed and implemented for patients with AILD in 3 referral centres in Europe during the present pandemic (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Management protocol for patients with autoimmune liver diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic.

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; AILD, autoimmune liver disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ER, emergency room; ERN, European reference network; GI, gastrointestinal; GP, general practitioner; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Patients should be stratified based on risk of complications to avoid unnecessary visits to the hospital. Indeed, patients with stable chronic AILD on long-term therapy are at low risk of complications and/or progression. While available data may suggest that immunosuppressed patients are not at increased risk of ARDS,6 a flare of AIH secondary to unnecessary drug reduction/withdrawal, would require a higher dose of steroids and thus potentially increased risk of infection. In this low-risk scenario, we suggest to: (i) postpone follow-up visits until the emergency is over; (ii) be proactive in sending general information and recommendations to your patients (i.e. mailing list) ahead of time; (iii) use web-based consultation upon request in addition to telephone-based consultations; and, (iv) organise drug dispensation with the local pharmacy for therapy maintenance.

Patients with cirrhosis, of any cause, that present with an acute complication are at high risk of morbidity and mortality independent of the viral epidemic. Indeed, severe flares of AIH, obstructive jaundice in primary sclerosing cholangitis, severe cholangitis, and/or gastrointestinal bleeding are associated with high short-term mortality and thus require urgent care and treatment. Even though the risk of COVID-19 in fragile patients seems to be relatively high, the underlying liver disease in these patients presents such a high-risk condition that hospital care is mandatory. We therefore suggest to: (i) organise an independent flow for urgent access to the hospital in order to avoid any contact with COVID-19 positive patients (e.g. avoid access through the general emergency department); (ii) limit invasive procedures such as endoscopy to emergency interventions avoiding screening, and follow local protocols in case of emergencies (i.e. obstructive jaundice, bleeding);7 (iii) start standard therapy at the usual dose for treatment of acute flare of AIH; (iv) coordinate care in case of hepatic failure with the regional transplant centre; finally, (v) in case of infection reduce immunosuppression – particularly antimetabolites in those with lymphopenia – and be timely in tapering steroids. Careful hospital hygiene procedures should be followed, and outpatient follow-up care organised in order to keep hospitalization as short as possible.

Finally, conditions conferring medium risk, including acute onset of symptoms in non-cirrhotic patients and chronic management of decompensated cirrhotic patients, should be consciously evaluated and managed to avoid unnecessary visits to the hospital.8 Although there is no available data, we indeed work under the assumption that pulmonary infection due to COVID-19 might lead to a worse outcome in these fragile populations. Non-cirrhotic clinically stable patients that present with abnormal liver tests should: (i) defer invasive diagnostic procedures that require hospital visits (i.e. liver biopsy); (ii) start empiric (i.e. steroids in AIH) therapy using web-based consultation; and (iii) establish a short-term web-based follow-up to define drug efficacy and adapt treatment accordingly. Thus, in this particular situation the diagnosis of AIH may be given without histology, if typical biochemical and serological results are followed by a convincing treatment response. Prove of the diagnosis can be undertaken later, either by a relapse upon therapy reduction, or a follow-up liver biopsy when conditions are safer. As already reported in China,8 advanced liver cirrhosis and decompensated patients can be monitored with a web-based system and all non-urgent medical visits should be postponed until the emergency is over. Urgent procedures (i.e. paracentesis) should be organised using a COVID-19-free path in the hospital, another COVID-19-free facility or home care. Finally, we recommend strict adherence to standard social distancing protocols and social isolation and emphasise, in cirrhotic patients, the importance of vaccination for Streptococcus pneumoniae and seasonal flu and of reinforcing social distancing measures. Further data are needed in order to demonstrate the real impact of COVID-19 infection in immunocompromised patients. Until then, and while vaccination is not available, we suggest continuing a cautious approach during low-level seasonal persistence of COVID-19 in the years to come.

Although we cannot currently evaluate the efficacy of our management protocol, we believe this framework might be a useful tool for management of AILD for the time being.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support to produce this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

AL, MC, PI, AL, AG: concept design and writing; all authors revised and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.002.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirchgesner J., Lemaitre M., Carrat F., Zureik M., Carbonnel F., Dray-Spira R. Risk of serious and opportunistic infections associated with treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:337–346.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaltsas A., Sepkowitz K. Community acquired respiratory and gastrointestinal viral infections: challenges in the immunocompromised host. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:423–430. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328355660b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients. The facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transpl. 2020 doi: 10.1002/lt.25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repici A., Maselli R., Colombo M., Gabbiadini R., Spadaccini M., Anderloni A. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao Y., Pan H., She Q., Wang F., Chen M. Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.