INTRODUCTION

Infectious diseases vary by geographic region and population, and they change over time. Increasingly, humans are moving from one region to another, thereby becoming exposed to a variety of potential pathogens and also serving as part of the global dispersal process.1 Microbes picked up at one time and in one place may manifest in disease far away in time and place. Because many microbes have the capacity of persisting in the human host for months, years or even decades, the relevant time frame for study of exposures becomes a lifetime. Furthermore, microbes also move and change and reach humans via multiple channels.

Caring for patients in today's world requires an understanding of the basic factors that underlie the geography of human diseases and events that cause shifts in the distribution and burden of specific diseases. Current technology contributes to massive population movements and rapid shifts in diseases and their distributions, but it also provides communication channels that can aid clinicians who care for patients with unfamiliar medical problems. This chapter reviews the factors that shape the global distribution of infectious diseases and the forces that are expected to shift distributions in the future. Several examples are used to illustrate the broad range of factors that affect the distribution and expression of infectious diseases.2

Many authors have traced the origins and spread of specific infectious diseases through human history. A century and a half ago, John Snow noted that epidemics of cholera followed major routes of commerce and appeared first at seaports when entering a new region. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, accompanied trade caravans and moved across oceans with rats on ships. Exploration of the New World by Europeans introduced a range of human pathogens that killed one-third or more of the local populations in some areas of the Americas. The plants and animals introduced as a result of this exploration have also had profound and long-lasting consequences for the ecology and economics of the new environment.3 The speed, reach and volume of today's travel are unprecedented in human history and offer multiple potential routes to move biologic species around the globe. Pathogens of animals and plants are being transported as well, and this can affect global food security.4 Establishment of arthopod vectors, such as mosquitoes that are competent to transmit human pathogens, in new geographic areas can expand the regions that are vulnerable to outbreaks of some vector-borne infections. This chapter focuses only on pathogens that directly affect human health and on their sources (Table 101.1 ). When thinking about geography of human infections, it is useful to consider both the origin of the organism and the conveyor or immediate source for the human (Fig. 101.1 ).

Table 101.1.

Origins and conveyors of human pathogens*

| Origin or carrier | Conveyor or immediate source | Examples of disease |

|---|---|---|

| Humans | Humans | HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B |

| Humans | Humans (air-borne pathogen) | Measles, tuberculosis |

| Soil | Soil, air-borne | Coccidioidomycosis |

| Soil | Food | Botulism |

| Animals | Water | Leptospirosis |

| Humans | Mosquitoes | Malaria, dengue |

| Humans | Soil | Hookworm, strongyloidiasis |

| Animals | Ticks | Lyme disease |

| Animals, humans | Sand flies | Leishmaniasis |

| Animals | Animals | Rabies |

| Rodents | Rodent excreta | Hantaviruses |

| Humans | Water, marine life | Cholera |

| Humans or animals (with snails as essential intermediate host) | Water | Schistosomiasis |

| Humans | Food, water | Typhoid fever |

| Animals | Water | Cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis |

Some pathogens have multiple potential sources.

Fig. 101.1.

Life cycles of some important pathogens.

This chapter addresses three key issues:

-

•

factors influencing geographic distribution: why are some infectious diseases found only in focal geographic regions or in isolated populations?

-

•

factors influencing the burden of disease: why does the impact from widely distributed infections vary markedly from one region or one population to another? and

-

•

factors influencing emergence of disease: what allows or facilitates the introduction, persistence and spread of an infection in a new region and what makes a region or population resistant to the introduction of an infection?

FACTORS INFLUENCING GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION

In past centuries, lack of interaction with the outside world could allow an infection to remain geographically isolated. Today, most infections that are found only in focal areas have biologic or geoclimatic constraints that prevent them from being introduced into other geographic regions. For example, the fungus Coccidioides immitis, which causes coccidioidomycosis, thrives in surface soil in arid and semiarid areas with alkaline soil, hot summers and short, moist winters; it is endemic in parts of south-western USA, Mexico and Central and South America. People become infected when they inhale arthroconidia from soil. An unusual wind storm in 1977 lifted soil from the endemic region and deposited it in northern California, outside the usual endemic region.5 In general, infection is associated with residence in or travel through the endemic region. However, because the fungus can persist in the human host for years, even decades, after initial infection (which may be mild and unrecognized), disease may be diagnosed far from the endemic regions. Although it is a ‘place’ disease, coccidioidomycosis has increased in the southwestern USA in recent years, in part attributable to a large influx of susceptible humans into the endemic zone and construction and other activities that disturb the soil. Outbreaks are also linked to climatic and environmental changes.6

Vectors

Many microbes require a specific arthropod vector for transmission or an animal reservoir host and hence inhabit circumscribed regions and may be unable to survive in other habitats. Malaria is a vector-borne infection that cannot become established in a region unless a competent vector is present. The presence of a competent vector is a necessary but not sufficient condition for human infection. The mosquito must have a source of malarial parasites (gametocytemic human or rarely other species), appropriate bioclimatic conditions and access to other humans. The ambient temperature influences the human biting rate of the mosquito, the incubation period for the parasite in the mosquito and the daily survival rate of the mosquito. Prevailing temperature and humidity must allow the mosquito to survive long enough for the malarial parasite to undergo maturation to reach an infective state for humans. Competent vectors exist in many areas without malaria transmission, because the other conditions are not met. These areas are at risk of the introduction of malaria, as illustrated by several recent examples in the USA and elsewhere.7, 8

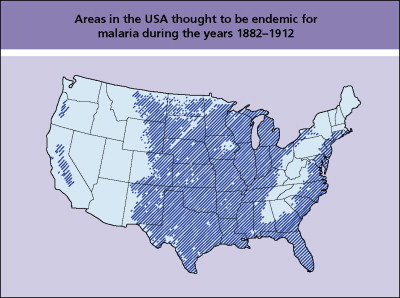

An estimated 77% of the world population lived in areas with malaria transmission in 1900. Today about 48% live in at-risk areas, but because of population growth and migration the total global population exposed to malaria today has increased by 2 billion since 1900.9 Malaria was endemic in many parts of the USA into the 20th century (Fig. 101.2 ), with estimates of more than 600 000 cases in 1914. Even before extensive mosquito control programs were instituted, transmission declined. Demographic factors (population shifts from rural to urban areas), improved housing with screened doors and windows, and the availability of treatment were among the factors that contributed to this decrease.

Fig. 101.2.

Areas of the USA thought to be endemic for malaria during the years 1882–1912.

The distribution of onchocerciasis in Africa is notable for its association with rivers.10 The reason becomes clear by understanding that the vector of this filarial parasite, the black fly (genus Simulium), lays her eggs on vegetation and rocks of rapidly flowing rivers and usually inhabits a region within 5–10 km on either side of a river. Another name for onchocerciasis, river blindness, describes the epidemiology as well as one consequence of infection.

Some pathogens have a complex cycle of development that requires one or more intermediate hosts. Distribution may remain relatively fixed, even when infected humans travel widely, if other regions do not supply the right combination and geographic proximity of hosts (Fig. 101.3 ). Although persons with schistosomiasis visit many regions of the world, the parasite cannot be introduced into a new region unless an appropriate snail host is present, excreted eggs (in urine or feces) are released into water where they reach the snail hosts and humans subsequently have contact with the untreated water.11 Local ecologic changes and climate change, however, can be associated with expansion of transmission in endemic areas or increased intensity of transmission, as has been projected as a possible consequence of warming temperatures in China.12

Fig. 101.3.

Worldwide distribution of schistosomiasis.

Many hantaviruses exist worldwide with distributions that are still being defined. Each hantavirus seems to have its specific rodent reservoir with which it has evolved. As with many zoonoses, humans are incidental to the survival of the virus in rodents, yet humans can develop severe and sometimes fatal disease if they enter an environment where they are exposed to the virus. Undoubtedly, other rodent-associated viruses and other pathogens (as well as pathogens associated with other animals or insects) with the capacity to infect humans will be identified as humans enter unexplored environments in the future.

Ebola and Marburg viruses are other viruses that have focal distributions but have caused dramatic human outbreaks with high mortality. They also infect nonhuman primates and threaten the survival of great apes.13 Recent studies suggest that bats may be the reservoir hosts.14, 15 Because these infections can be spread from person to person, secondary household and nosocomial spread in several instances has amplified what began as an isolated event. Lack of adequate resources in hospitals in many developing regions contributes to the spread of infections within hospitals and to persons receiving outpatient care, such as those receiving injections.

Cultural practices can lead to unusual infections in isolated areas. Residents of the highlands of Papua New Guinea developed kuru after ingestion (or percutaneous inoculation) of human tissue during the preparation of the tissues of dead relatives.

Thus, the presence of a pathogen in a region may reflect the biologic properties of the organism, its need for a certain physicochemical environment or its dependence on specific arthropods, plants or animals to provide the milieu where it can sustain its life cycle (Table 101.2 ). The presence of a pathogen in a region does not necessarily equate with human disease, because mechanisms must exist for the pathogen to reach a susceptible human host for human disease to occur. Sometimes it is only with exploration of new regions or changes in land use that humans place themselves in an environment where they come into contact with microbes that were previously unidentified or unrecognized as human pathogens. Preferences for specific foods, certain preparation techniques or cultural traditions may place one population at a unique risk for infection.

Table 101.2.

Biologic attributes of organisms that influence their epidemiology

|

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE BURDEN OF DISEASE

Among the infectious diseases that impose the greatest burden of death globally, most are widely distributed: respiratory tract infections (e.g. influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae and others), diarrheal infections, tuberculosis, measles, AIDS and hepatitis B.16 Most of these infections are spread from person to person. The World Health Organization estimated that about 65% of infectious diseases deaths globally in 1995 were due to infections transmitted from person to person (Table 101.3 ).16

Table 101.3.

Modes of transmission for major global infectious diseases

| Mode of transmission | % of total* |

|---|---|

| Person-to-person | 65 |

| Food-borne, water-borne or soil-borne | 22 |

| Insect-borne | 13 |

| Animal-borne | 0.3 |

The figures are based on an estimated 17.3 million deaths due to infectious diseases in 1995, as reported by the World Health Organization.16

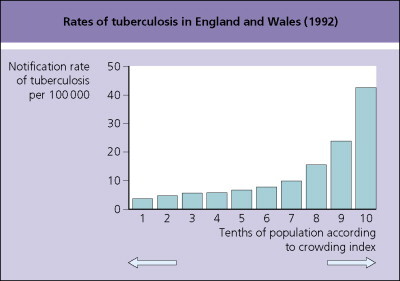

Burden from these diseases is unevenly distributed across populations and among different countries. Poor sanitation, lack of clean water, crowded living conditions and lack of vaccination contribute to the disproportionate burden from many of these infections in developing regions of the world. In industrialized countries, pockets of high risk persist. Disadvantaged populations have higher rates of tuberculosis, HIV and many other infectious and noninfectious diseases. Rates of reported cases of tuberculosis vary widely by region (Table 101.4 ).17 Variation also exists within countries. Figure 101.4 shows the effect of crowded living conditions on rates of tuberculosis in England and Wales in 1992.18 Among welfare applicants and recipients addicted to drugs or alcohol in New York City, the rate of tuberculosis was 744 per 100 000 person years or more than 70 times the overall rate for the USA.19 The impact of an infection derives not only from the risk of exposure but also from the access to effective therapy. For example, treatment of a patient with active tuberculosis can cure the individual and eliminate a source of infection for others in the community.

Table 101.4.

Rates of reported cases of tuberculosis worldwide by region, 1990 and 2006

| Region | Incidence Per 100 000 Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2006 | |

| Africa | 162 | 363 |

| Americas | 65 | 37 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 111 | 105 |

| Europe | 37 | 49 |

| South East Asia | 200 | 180 |

| Western Pacific | 127 | 109 |

Data from World Health Organization.17

Fig. 101.4.

Rates of tuberculosis in England and Wales by crowding index (1992).

Adapted from Bhatti et al.18

Diphtheria, controlled in many parts of the world through the use of immunization, resurged in new independent states of the former Soviet Union in the 1990s, a reminder of the tenuous control over many infectious diseases. Populations in other countries also felt the impact as cases related to exposures in the Russian Federation were reported in Poland, Finland, Germany and the USA. Serologic studies in America and Europe suggest that up to 60% of adults may be susceptible to diphtheria.

Travelers to tropical and developing regions of the world can pick up geographically focal, often vector- or animal-associated infections (such as malaria and dengue),20 but travelers most often acquire infections with a worldwide distribution that are especially common in areas lacking good sanitation.21 Food- and water-borne infections are common and lead to travelers’ diarrhea, which is caused by multiple agents (including Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter spp., and others), typhoid fever and hepatitis A. Respiratory tract infections may be acquired from other travelers from all over the globe during the crowding that occurs in travel (e.g. in buses, airplanes, terminals and on cruise ships) as well as from persons in the local environment. Tables 101.5 and 101.6 note factors that influence the types and abundance of microbes in a community and the probability of exposure to pathogens.

Table 101.5.

Factors that influence the types and abundance of microbes in a community

|

Table 101.6.

Factors that influence the probability of exposure to pathogens

|

Hepatitis A virus remains a common cause of infection in developing regions of the world although it is not considered a major cause of morbidity or mortality in those regions where most persons are infected at a young age and become immune for life. The presence and severity of symptoms are related to the age at which a person becomes infected. Infection in young children is typically mild or inapparent. Persons living in areas of high transmission may be unaware of the presence of high levels of transmission, although nonimmune, older people (such as travelers) who enter the environment may develop severe, and occasionally fatal, infection. Some countries with an improving standard of living have noted a paradoxic increase in the incidence of disease from hepatitis A virus as the likelihood of exposure at a young age decreases, shifting upward the age of infection to a time when jaundice and other symptoms are more likely to occur.

Travelers may also contribute to the spread of infectious diseases and influence the global burden of these diseases.22, 23 Neisseria meningitidis, a global pathogen, occurs in seasonal epidemics in parts of Africa – the so-called meningitis belt (Fig. 101.5 ).24 Irritation of the throat by the dry, dusty air probably contributes to invasion by colonizing bacteria. Pilgrims carried an epidemic strain of group A N. meningitidis from southern Asia to Mecca in 1987. Other pilgrims who became colonized with the epidemic strain introduced it into sub-Saharan Africa, where it caused a wave of epidemics in 1988 and 1989. Using molecular markers, investigators were able to trace the spread of the epidemic clone to several other countries.25 In 1996 in Africa, major outbreaks of meningococcal meningitis occurred(>185 000 reported cases with a case fatality rate of ∼10%) caused by N. meningitidis serogroup A, clone III-1.26 A virulent group C, ET-15 strain of N. meningitidis spread in Canada and was associated with an increased case fatality rate and a higher proportion of cases in persons over the age of 5 years.27 In these examples, the virulence of the microbe and travel and trade acted synergistically to change the epidemiology and burden of disease. In the spring of 2000 serogroup W135 N. meningitidis caused an outbreak of infection in pilgrims to the Hajj and subsequently spread to their contacts and others around the world. Studies using serotyping, multilocus sequence typing, multilocus DNA fingerprints and other techniques found identical W135 isolates in multiple countries. Pilgrims are required to receive a meningococcal vaccine but before this outbreak, pilgrims from many countries received a vaccine that protected against serotype A but not W135. The vaccine reduces risk of disease but does not prevent oropharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis.28

Fig. 101.5.

Meningitis belt in Africa.

FACTORS INFLUENCING EMERGENCE OF DISEASE

Regular, rapid movement of persons from tropical regions to major urban areas throughout the world raises concerns that unusual infections could be introduced into an environment where they could spread to large populations. In order to assess the potential for a pathogen to be introduced into a new population, information is required about the biologic properties of the organism, the region and population being considered and the mechanisms of transmission (see Table 101.1). A key factor that determines whether a pathogen can persist and spread in a new population is its basic reproductive rate, which is the number of secondary infections produced in a susceptible population by a typical infectious individual. To become established in a new host population, a pathogen must have a basic reproductive rate that exceeds one. The concept is simple but invasion and persistence are affected by a range of biologic, social and environmental factors. Also critical in determining how easily an infection can be controlled is the proportion of transmission that occurs before onset of symptoms or during asymptomatic infection.29

Certain factors restrict the introduction and spread or persistence of infection in a region (Table 101.7 ); many of these are discussed above. Nutrition is also important in determining susceptibility to and severity of many infections. A substantial proportion of disease burden in developing countries can be attributed to childhood and maternal underweight and micronutrient deficiences.30 Before measles vaccine was introduced, the epidemiology of measles exhibited marked periodicity in large populations, with peaks typically occurring every 2–3 years.31 In general, a community size of about 250 000 is necessary to provide a sufficient number of susceptible people to sustain the virus. In small island communities (or other isolated populations), outbreaks typically occur only after periodic introductions from outside. Size and density of a population thus influence the epidemiology of some infections. It has been suggested that measles as it has been known in the 20th century could not have established itself much before 3000 bc because before that time human populations had not achieved sufficient size to sustain the virus. Measles could not have persisted in nomadic, hunting communities.

Table 101.7.

Factors that restrict the introduction and spread of infections

|

Examples of emerging pathogens

It is instructive to look at examples of infections that have recently undergone major shifts in distribution and to review the key factors that have influenced their geographic spread. They are a reminder of the complexity of the interactions among host, microbe and environment. A recurring theme is the movement of humans who introduce pathogens into a new region (see also Chapter 4) and human alteration of the landscape or ecology that permits contact with previously unrecognized microbes, often through interaction with animals or animal products. Many infections in humans, in the past and in recent years, have domestic or wild animals as their sources.32

Human immunodeficiency virus and other pathogens carried by humans

Organisms that survive primarily or entirely in the human host and are spread from person to person (e.g. by sexual or other close contact or by droplet nuclei) can be carried to any part of the world. The spread of HIV in the past three decades to all parts of the world is a reminder of the rapid and broad reach of travel networks. Although the infection has also spread via blood and shared needles, it has been the human host engaging in sex and reproduction who has been the origin for the majority of the infections worldwide. Person-to-person spread accounted for the rapid worldwide distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a coronavirus infection, in the spring of 2003, after the virus emerged from an animal reservoir, most likely bats.33

Drugs or vaccines injected by reused inadequately sterilized needles and syringes have been and continue to be an important means of spread of blood-borne infections, such as hepatitis C, hepatitis B and HIV, in some parts of the world.34

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis has continued to increase, with World Health Organization estimates of 500 000 new cases of MDR annually (now about 5% of all new TB cases each year).35 Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, which is virtually untreatable, had been reported in 45 countries by 2007. It is not only the pathogens carried by humans that are relevant. Humans also carry resistance and virulence factors that can be transferred to and exchanged with other microbes.36

Dengue fever

(See healthmap.org for outbreaks of Dengue fever)

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne viral infection that has now spread to most tropical and subtropical regions of the world and continues to increase in incidence and severity. Viremic humans regularly enter regions infested with Aedes aegypti, the principal vector of dengue, transporting the virus for new outbreaks. Infection can spread rapidly and outbreaks are sometimes massive, involving >30% of the population. Because four serotypes of dengue virus exist and infection with one serotype does not confer lasting immunity against other serotypes, a person can be infected more than once. The risk of developing severe dengue (e.g. dengue shock syndrome or dengue hemorrhagic fever, DSS or DHF) after repeat infection is 82–103 times greater than after primary infection.37 In an outbreak in Cuba, 98.5% of cases of DSS or DHF were in persons with a prior dengue infection. The rate of DSS or DHF was 4.2% in persons with prior dengue infection who became infected with a new serotype.38

Geographic regions where multiple serotypes are circulating have continued to expand, setting the stage for more severe consequences of infection. Factors that have aided the spread of dengue include increasing (and rapid) travel to and from tropical regions; expansion of the regions infested with Aedes aegypti; increasing urbanization, especially in tropical areas, which has provided large, dense populations; the use of nonbiodegradable and other containers that make ideal breeding sites for the mosquito; and lack of support for vector control programs.

Most of the world population growth globally is in urban/periurban areas in tropical and developing regions. The expectation is that more urban areas in tropical regions will reach the critical population size, perhaps somewhere between 150 000 and 1 million people, to permit sustained transmission of dengue, and to increase the risk of the severe forms of infection, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.

In 2001 the vector that was implicated in an outbreak of dengue in Hawaii39 was Aedes albopictus, a mosquito species that has been newly introduced into many new regions in recent decades, probably primarily by shipping.40 On phylogenic analysis the virus responsible for the Hawaii outbreak was similar to dengue, isolates from Tahiti, suggesting that viremic travelers introduced the virus from the South Pacific.

It is instructive to ask not only where dengue occurs but also where it does not. Although large dengue epidemics occurred in the USA in the 20th century, only a handful of cases have been acquired in the USA in recent years, despite the presence of epidemic disease in adjacent areas of Mexico and the presence of a competent vector (Aedes aegypti) in south-eastern USA (Fig. 101.6 ).24 It is possible that the presence of screened dwellings and air conditioning may make an area relatively resistant to the introduction of infection, even if a competent vector infests a region, though serologic studies have also documented that unrecognized dengue infections are occurring in Texas.41

Fig. 101.6.

(a, b) Areas reporting dengue fever, 2005. Many areas with a competent vector do not report dengue epidemic activity.

Copyright World Health Organization 2008.

Chikungunya virus

(See healthmap.org for outbreaks of Chikungunya)

Chikungunya, a mosquito-borne alphavirus originally isolated in Tanzania in 1953, has spread from Africa, causing massive outbreaks in the Indian Ocean islands and India since 2005. Although it has typically been considered an infection of tropical regions, in the summer of 2007 an outbreak caused hundreds of cases (175 laboratory confirmed) in north-eastern Italy. The index case was a visitor from India. Of note, the vector implicated was Aedes albopictus, which had been first documented in Italy in 1990 and was postulated to have been introduced via used tires.42 Mutations in the virus may have enabled it to replicate more efficiently in the mosquito vector. Chikungunya virus can be transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which are now both widely distributed, so many regions of the world are vulnerable to introduction of this virus by viremic travelers.

Cholera

(See healthmap.org for outbreaks of Cholera)

Cholera illustrates the complex interactions between microbe, environment and host.43 Epidemics are seasonal in endemic regions. Vibrio cholerae lives in close association with marine life, binding to chitin in crustacean shells and colonizing surfaces of algae, phytoplankton, zooplankton and water plants. V. cholerae can persist within the aquatic environment for months or years, often in a viable but dormant state, nonculturable by usual techniques. Environmental factors, including temperature, salinity, pH and sea-water nutrients, affect the persistence, abundance and viability of the organisms, and hence have a striking influence on human epidemics.

Under conditions of population crowding, poor sanitation and lack of clean water, cholera can have a devastating impact, as was shown by the massive outbreak of El Tor cholera in Rwandan refugees in Goma, Zaire, which caused 12 000 deaths in July 1994.44

The organism can be carried by humans, who sometimes have few or no symptoms, and introduced into new regions. Trade probably also plays a critical role. Ballast water, picked up by boats in multiple locations and discharged at another time and place, carries a wide range of species, including many that have no direct impact on human health.45, 46 In studies of the ballast and bilge of cargo ships in the USA Gulf of Mexico, researchers were able to identify V. cholerae identical to the strains causing epidemic disease in Latin America.47

Food-borne disease

(See healthmap.org for outbreaks of Food-borne disease)

The globalization of the food market means pathogens from one region can appear in another; some are common pathogens with a worldwide distribution but others are not. An outbreak of cholera in Maryland, USA, was traced to imported, contaminated commercial frozen coconut milk.48 Alfalfa sprouts grown from contaminated seed sent to a Dutch shipper caused outbreaks of infections with Salmonella spp. on two continents, in at least Arizona and Michigan in the USA and in Finland.49 Commercial movement of fruits and vegetables redistributes resistance factors along with the microbes. Tracing the source after an infection has been diagnosed can be convoluted and often is not carried out unless disease is severe, lethal or epidemic or involves a highly visible person or population.

Travel and trade are key features in the epidemiology of the infection Cyclospora, a cause of gastroenteritis. Recognized for many years in multiple regions of the world, cases were often associated with living in or travel to areas where sanitary facilities were poor. In the summer of 1996, a large US outbreak occurred in persons who had not traveled. Over a period of a few months, 1465 cases of cyclosporiasis were reported from 20 states. The outbreak was linked to eating raspberries imported from Guatemala.50 During some seasons of the year up to 70% of selected fruits and vegetables sold in the USA come from developing countries.

Visceral leishmaniasis

In the past, visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil was primarily a rural disease. Recently, however, several cities have reported large outbreaks of visceral leishmaniasis.51 Reasons for the change in epidemiology include geoclimatic and economic factors (drought, lack of farm land, famine), leading to migration of large numbers of persons, who settle in periurban areas where they live in densely crowded shanties, lacking basic sanitation. The presence of domestic animals, such as dogs, chickens and horses, in and adjacent to human dwellings provides ample sources of blood meals for the sand fly, the vector of leishmaniasis. Outbreaks have occurred in many cities in Brazil, including Teresina, São Luis and Natal. Children and young people have been most affected. Malnutrition can also contribute to the severity of the disease.

Disease–disease interactions can also alter the epidemiology of infections. Visceral leishmaniasis has become an important infection in HIV-infected people in Spain and other areas where the two infections coexist.52 The presence of HIV leads to increased risk of progression of infection; late appearance of disease can occur years to decades after exposure in an endemic region, leading to the appearance of cases of leishmaniasis in regions distant from endemic areas. A common consequence is missed or delayed diagnosis.

Movement of vectors and other species

Movement today involves all forms of life and the movement of nonhuman species can affect infections in humans. Importation of wild animals from Ghana into the United States led to an outbreak of monkeypox, an infection previously known to exist in Africa. Humans became infected by handling prairie dogs (sold as pets) that had been housed with the imported wild animals from Africa.53 Aedes albopictus introduced into the USA via used tires shipped from Asia54 has since become established in at least 21 contiguous states of the USA and in Hawaii. Aedes albopictus can transmit dengue and chikungunya viruses, as described above, and is a competent laboratory vector of La Crosse, yellow fever and other viruses. It is also hardier than many other mosquito species and therefore may spread widely and be extremely difficult to eradicate. Multiple strains of eastern equine encephalitis virus have been isolated from Aedes albopictus in Florida.

An example from the past illustrates the potential consequences of the introduction of a mosquito vector into a new region. In March 1930, an entomologist in Natal, Brazil, came upon Anopheles gambiae larvae in a small, wet, grassy field between a railway and a river.55 He was surprised, because the usual habitat for this mosquito was Africa. Investigation revealed that the probable route of entry into South America was via boats that made mail runs between Dakar in Senegal and Natal in Brazil, covering the 3300 km in less than 100 hours. In Dakar the boats were anchored a distance from the shore within easy flight range of A. gambiae. In Brazil, over the ensuing years, the mosquito spread along the coastal region and inland. Natal, as an ocean port, terminus of two railway lines and the hub of truck, car and river transportation, was well suited for dissemination of A. gambiae into the region. Although malaria already existed in the region, the local mosquitoes were not efficient vectors. Anopheles gambiae, in contrast, lived in close proximity to humans, entered houses, sought human blood and was an efficient biter. In 1938 and 1939, devastating outbreaks of malaria killed more than 20 000 persons. In this instance, the simple introduction of a new vector into a region led to severe problems. Fortunately, an intensive (and expensive) eradication campaign was effective.

Current transportation systems regularly carry all forms of life, including potential vectors, along with people and cargo. In an experiment carried out several years ago, mosquitoes, house flies and beetles in special cages were placed in wheel bays of 747 aircraft and carried on flights lasting up to 7 hours. Temperatures were as low as –62°F (–52°C) outside and ranged from 46°F to 77°F (8–25°C) in the wheel bays. Survival rates were greater than 99% for the beetles, 84% for the mosquitoes and 93% for the flies.56 Occasional cases of so-called airport malaria – cases of malaria near airports in temperate regions – attest to the occasional transport and survival of a commuter mosquito long enough to take at least one blood meal in the new environment.

In the USA, transportation of raccoons in the late 1970s from Florida to the area between Virginia and West Virginia (in order to stock hunting clubs) unintentionally introduced a rabies virus variant into the animals of the region. From there, the rabies enzootic spread for hundreds of miles, reaching raccoons in suburban and densely populated regions of the north-east USA. Spill-over of the rabies virus variant into cats, dogs and other animal populations and direct raccoon–human interactions have had extremely costly and unpleasant consequences.57

Today highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) is a global concern.58 It is entrenched in poultry populations in Asia and Africa and has caused outbreaks in Europe and the Middle East. Although the virus causes high mortality in infected humans, thus far H5N1 has not been able to establish sustained transmission from person to person. Most humans appear to have been infected via close contact with poultry or their products. Although the virus can be carried by migratory birds,59 most introductions appear to have been related to movement of poultry and poultry products. A model designed to map risk in South East Asia found risk was associated with duck abundance, human population and rice cropping intensity.60

GEOGRAPHIC INFLUENCES ON DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Geographic exposures influence how one thinks about probable diagnoses in a given patient. In Mexico, for example, more than 50% of patients with late-onset seizures have CT evidence of the parasitic infection, neurocysticercosis.61 In Peru, 29% of persons born outside Lima who had onset of seizures after 20 years of age had serologic evidence of cysticercosis.62 In northern Thailand, melioidosis is a common cause of sepsis, accounting for 40% of all deaths from community-acquired sepsis.63

In considering the consequences of exposures in other geographic regions, relevant data in assessing the probability of various infections include the duration of visit, activities and living conditions during the stay and the time lapsed since the visit. Among British travelers to West Africa, the relative risk of malaria was 80.3 times higher for persons staying for 6–12 months than among those staying 1 week.64 In Malawi, the risk of schistosome infection increased directly with duration of stay. Seroprevalence was 11% for those present for 1 year or less, but this increased to 48% among those present for 4 years or longer.65 In a study of persons with cysticercosis, the average time between acquisition of infection and onset of symptoms was about 7 years.66

For malaria, it is necessary to know not only whether infection can be acquired in a specific location but also the specie of parasite present and the patterns of resistance to antimalarial agents. As chloroquine resistance has spread, maps now typically highlight the few remaining areas of chloroquine sensitivity. Because the resistance to antimalarial agents is a dynamic process, with levels of resistance generally increasing over time (involving Plasmodium vivax in some areas as well as P. falciparum), it is essential to base decisions about chemoprophylaxis and treatment on up-to-date information. Figure 101.7 shows the distribution of malaria and resistance patterns globally as of 2005. Recent analysis of data from a network that uses travelers as a sentinel population found marked differences in the spectrum of disease in relation to the place of exposure.20

Fig. 101.7.

(a, b) Worldwide distribution of malaria (updated CDC map).

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.24

Expression of disease may vary depending on age of first exposure, immunologic status of the host, genetic factors and the number and timing of subsequent exposures. Temporary residents of endemic regions have different patterns of response to a number of helminths from those of long-term residents. In cases of loiasis, temporary residents have immunologic hyperresponsiveness, high-grade eosinophilia and severe symptoms that are not seen in long-term residents of the same area.67 Genetic factors can affect susceptibility to infection or expression of disease. Some persons, for example, are genetically resistant to infection with parvovirus because they lack appropriate receptors on their erythrocytes.68 Persons lacking Duffy factor cannot be infected with the malarial parasite, P. vivax.

CONCLUSION

Knowledge about the geographic distribution of diseases is essential for informed evaluation and care of patients, who increasingly have had exposures in multiple geographic regions. Recent travel and trade patterns have led to more frequent contact with populations (human and nonhuman species) from low latitude areas, regions with greater species richness.69 Infectious diseases are dynamic and will continue to change in distribution. Changes in virulence and shifts in resistance patterns will also require ongoing surveillance and communication to health-care providers. Multiple factors favor even more rapid change, perhaps in unexpected ways, in the future: rapidity and volume of travel, increasing urbanization (especially in developing regions), the globalization of trade, multiple technologic changes that favor mass processing and broad dispersal, and the backdrop of ongoing microbial adaptation and change, which may be hastened by alterations in the physicochemical environment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson M.E. Travel and emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:39–46. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.950201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson M.E. Infectious diseases: an ecological perspective. BMJ. 1995;311:1681–1684. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7021.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby A.W., Jr . The Columbian exchange. Greenwood Press; Westport, Connecticut: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson M.E., Levins R., Spielman A., editors. Disease in evolution: global changes and emergence of infectious diseases. New York Academy of Sciences; New York: 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn N.M., Hoeprich P.D., Kawachi M.M. An unusual outbreak of windborne coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:358–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908163010705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park B.J., Sigel K., Vaz V. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis in Arizona associated with climatic changes, 1998–2001. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1981–1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maldonado Y.A., Nahlen B.L., Roberto R.R. Transmission of Plasmodium vivax malaria in San Diego County, California, 1986. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:3–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson M.E. Changing geography of malaria. In: Schlagenhauf P., editor. Travelers’ malaria. BC Decker; Hamilton, Canada: 2008. pp. 352–362. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay S.I., Guerra C.A., Tatem A.J. The global distribution and population at risk of malaria: past, present, and future. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(6):327–336. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO expert committee on onchocerciasis control. 1995. Geneva World Health Organization Technical Report Series No. 852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO expert committee. 2002. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Geneva World Health Organization Technical Report Series No. 912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X.-N., Yang G.-J., Yang K. Potential impact of climate change on schistosomiasis transmission in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78(2):188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leroy E.M., Rouquet P., Formenty P. Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife. Science. 2004;303:387–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1092528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leroy E.M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438:575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Towner J.S., Pourrut X., Albariño C.G. Marburg virus infection detected in a common African bat. PLoS ONE. 2007;8:e764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . Fighting disease, fostering development. WHO; Geneva: 1996. The world health report 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . WHO Report 2008: global tuberculosis control. WHO; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatti N., Law M.R., Morris J.K., Halliday R., Moore-Gillon J. Increasing incidence of tuberculosis in England and Wales: a study of the likely causes. BMJ. 1995;310:967–969. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6985.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fineberg H.V., Wilson M.E. Social vulnerability and death by infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:859–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman D.O., Weld L.H., Kozarsky P.E. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):119–130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan E.T., Wilson M.W., Kain K. Illness after international travel. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:505–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson M.E. The traveller and emerging infections: sentinel, courier, transmitter. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:1S–11S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson M.E., Chen L.H. Travel. In: Mayer K., Pizer H.F., editors. Social ecology of infectious diseases. Academic Press; London: 2007. pp. 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Health information for international travel 2008. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services; Atlanta: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore P.S., Reeves M.W., Schwartz B., Gellin B.G., Broome C.V. Intercontinental spread of an epidemic group A Neisseria meningitidis strain. Lancet. 1989;2:260–263. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization Meningitis in Chad. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 1998;73:126. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whalen C.M., Hockin J.C., Ryan A., Ashton F. The changing epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in Canada, 1985 through 1992. Emergence of a virulent clone of Neisseria meningitidis. JAMA. 1995;273:390–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taba M.K., Achtman M., Alouso J.M. Serogroup W135 meningococcal disease in Hajj pilgrims. Lancet. 2000;356:2159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser C., Riley S., Anderson R.M., Ferguson N.M. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. PNAS. 2004;101:6146–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ezzati M., Lopez A.D., Rogers A. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cliff A., Haggett P., Smallman-Raynor M. An historical geography of a major human viral disease from global expansion to local retreat, 1940–1990. Blackwell Publishers; Oxford: 1993. Measles. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe N.D., Dunavan C.P., Diamond J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature. 2007;447:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature05775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau S.K.P., Woo P.C.Y., Li K.S.M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. PNAS. 2005;102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drucker E., Alcabes P.G., Marx P.A. The injection century: massive unsterile injections and the emergence of human pathogens. Lancet. 2001;358:1989–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06967-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world: Report No. 4. WHO; Geneva: 2008. WHO/IUATLD global project on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance surveillance. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okeke I.N., Edelruan R. Dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria across geographic borders. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:364–369. doi: 10.1086/321877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thein S., Aung M.M., Shwe T.H. Risk factors in dengue shock syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:566–572. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guzman M.G., Kouri G., Valdes L. Epidemiologic studies on dengue in Santiago de Cuba, 1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:793–799. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Effler P.V., Pang L., Kitsutani P. Dengue fever, Hawaii 2001–2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(5):742–749. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.041063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tatem A.J., Hay S.L., Rogers R.J. Global traffic and disease vector dispersal. PNAS. 2006;103(16):6242–6247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508391103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunkard J.M., Lopez J.L.R., Ramirez J. Dengue fever seroprevalence and risk factors, Texas–Mexico border, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(10):1477–1482. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.061586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezza G., Nicoletti L., Angelini R. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colwell R.R. Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science. 1996;274:2025–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goma Epidemiology Group Public health impact of Rwandan refugee crisis: what happened in Goma, Zaire, in July, 1994. Lancet. 1995;345:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlton J.T., Geller J.B. Ecological roulette: the global transport of non-indigenous marine organisms. Science. 1993;261:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5117.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Committee on Ship's Ballast Operations Marine Board Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems, National Research Council . Stemming the tide. Controlling introductions of nonindigenous species by ships’ ballast water. National Academy Press; Washington DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy S.A., McPhearson R.M., Guarino A.M. Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 and cargo ships entering the Gulf of Mexico. Lancet. 1992;339:624–625. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90918-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor J.T., Tuttle J., Pramukul T. An outbreak of cholera in Maryland associated with imported commercial frozen fresh coconut milk. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1330–1335. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahon B.E., Ponka A., Hall W.N. An international outbreak of Salmonella infections caused by alfalfa sprouts grown from contaminated seeds. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:876–882. doi: 10.1086/513985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herwaldt B.L., Ackers M.-L. Cyclospora Working Group. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1548–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705293362202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeronimo S.M.B., Oliveira R.M., Mackay S. An urban outbreak of visceral leishmaniasis in Natal, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:386–388. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canto-Lara S.B., Perez-Molina J.A., Guerrero A. Clinicoepidemiologic characteristics, prognostic factors, and survival analysis of patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus and Leishmania in an area of Madrid, Spain. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:436–443. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed K.D., Melski J.W., Braham M.B. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiter P., Sprenger D. The used tire trade: a mechanism for the worldwide dispersal of container-breeding mosquitoes. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1987;3:494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soper F.L., Wilson D.B. Anopheles gambiae in Brazil, 1930–1940. The Rockefeller Foundation; New York City: 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russell R.C. Survival of insects in the wheel bays of a Boeing 747B aircraft on flights between tropical and temperate airports. Bull WHO. 1987;65:659–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fishbein D.B., Robinson L.E. Rabies. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1632–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311253292208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Writing Committee of the Second World Health Organization Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Human Infection with Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus. Update on avian influenza (H5N1) virus infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:261–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keawcharoen J., van Riel D., van Amerongen G. Wild ducks as long-distance vectors of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(4):600–607. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.071016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilbert M., Xiao X., Pfeiffer D.U. Mapping H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza risk in Southeast Asia. PNAS. 2008;105(12):4769–4774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710581105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medina M., Roasa E., Rubio F., Sotelo J. Neurocysticercosis as the main cause of late-onset epilepsy in Mexico. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcia H.H., Gilman R., Martinez M. Cysticercosis as a major cause of epilepsy in Peru. Lancet. 1993;341:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90064-n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaowagul W., White H.J., Dance D.A.B. Melioidosis: a major cause of community-acquired septicemia in northeastern Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:890–899. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips-Howard P.A., Radalowicz A., Mitchell J., Bradley D.J. Risk of malaria in British residents returning from malarious areas. BMJ. 1990;300:499–503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6723.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cetron M., Chitsulo L., Sullivan J.J. Schistosomiasis in Lake Malawi. Lancet. 1996;348:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)01511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dixon H.B.F., Harvreaves W.H. Cysticercosis (T. solium): a further ten years’ clinical study, covering 284 cases. Q J Med. 1944;13:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klion A.D., Massoughbodji A., Sadeler B.C., Ottesen E.A., Nutman T.B. Loiasis in endemic and nonendemic populations: immunologically mediated differences in clinical presentation. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1318–1325. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown K.E., Hibbs J.R., Gallinella G. Resistance to parvovirus B19 infection due to lack of virus receptor (erythrocyte P antigen) N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1192–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guernier V., Hochberg M.E., Guegan J.-F. Ecology drives the worldwide distribution of human diseases. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(6):740–746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]