Abstract

Human waste may contain high numbers of a variety of enteric pathogens. Diseases caused by these microorganisms include gastroenteritis, infectious hepatitis, cholera, typhoid, respiratory illness, myocarditis, encephalitis, and endocarditis. When this waste is treated in an on-site wastewater treatment system, such as a septic tank, the potential for contamination of the underlying groundwater exists. There are numerous factors that affect the potential for groundwater contamination by microorganisms in domestic waste, which are discussed herein.

Keywords: Domestic waste, Groundwater, Health risk, Septic tank, Waterborne disease, Waterborne pathogen

Introduction

On-site wastewater treatment is typically used in locations where housing density is sufficiently low that centralized wastewater treatment is not economically feasible. It is also used in areas where technology and resource limitations do not permit centralized wastewater treatment systems. The purpose of on-site wastewater treatment systems is to reduce the concentrations of contaminants to acceptable levels before the treated waste reaches water supplies or before people come into contact with it. Contaminants in domestic wastewater include organic chemicals (e.g., oil and grease), inorganic chemicals (e.g., heavy metals), nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), and disease-causing microorganisms, hereafter referred to as pathogens. The focus of this article will be on the potential health effects associated with exposure to pathogenic microorganisms that may be present in domestic waste.

On-Site Wastewater Treatment Systems

On-site wastewater treatment systems are those systems in which the wastes are stored (at least temporarily) at the site of disposal. Typically, some degree of decomposition of the waste material occurs on-site. On-site wastewater disposal systems include latrines and septic tanks. The advantages and disadvantages of selected on-site wastewater treatment systems are described in Table 1 . Because the waste materials are stored on-site, these systems can pose a hazard to the underlying groundwater as the liquid portion of the material can leach through the soil, carrying contaminants to the groundwater. A more detailed description of the factors that control the potential for off-site transport of pathogens will be provided later in the text.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of selected on-site wastewater treatment systems

| Sanitation system | Water requirements | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple pit latrine | Dry | Inexpensive, limited expertise needed for construction | Significant fly and odor problems, concerns by users over safety |

| Pour flush latrine | Wet, with low-volume water use | Low-volume water use, fly and odor problem controlled, convenient for users, easily upgraded | Increased cost compared to pit latrine, reliable water supply needed |

| Composting latrine | Dry | Humus produced as fertilizer/soil conditioner | Requires expertise to operate, sludge requires careful handling, some systems require urine separation, ash and vegetable matter must be added regularly |

| Urine separation | Dry, with urine collected separately | Provides humus used for fertilizer, urine can be used as fertilizer, low-cost systems available, reduces hydraulic load | Desludging requires careful handling, pathogens may not be inactivated in sludge pile, user education required, significant time spent in operation and maintenance |

| Septic tank | Wet, with high-volume water use | Convenient, limited fly and odor problems, wastes removed rapidly | High cost; in-house piped water generally required, large space requirement, regular desludging required, permeable soil required |

Source: Franceys R, Pickford J, and Reed R (1992) A Guide to the development of on-site sanitation. Geneva: WHO.

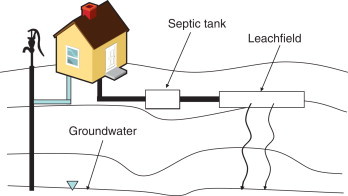

Septic tanks are among the most common types of on-site wastewater disposal systems used in industrialized countries. It is estimated that on-site disposal systems are used to treat the wastewater for up to 20% of the population of the United States, with 20–25 million systems in operation. Septic tanks consist of two components. The first is an underground tank (made of concrete or some other relatively inert material), which receives the wastewater generated in the house (Figure 1 ). The solid portion of the waste settles to the bottom of the tank; decomposition of the material occurs due to the presence of naturally occurring bacteria in the material. The liquid portion passes to the second component of the treatment system, the leach field. This consists of a series of perforated pipes, which are buried below the soil surface, typically in a constructed gravel layer. The liquid material leaches through the gravel and into the underlying soil material.

Figure 1.

Septic tank/leach field system.

The construction and operation of the leach field is critical to the proper functioning of the septic tank. The soil must be sufficiently permeable to allow the waste material to leach through at a rate that is fast enough that the waste does not build up and reach the soil surface. The size of the leach field must be properly determined so that it is large enough to handle the rate at which the liquid enters the leach field so that, again, there is sufficient capacity for leaching through the soil, rather than surfacing of the wastewater. In addition, the leach field must be situated so that there is an adequate separation distance between the leach filed and the groundwater and adequate removal of contaminants before the leachate reaching the groundwater (Figure 1).

Pathogens in Wastewater

There are hundreds of different types of microorganisms that may be present in domestic wastewater. The major groups of pathogenic microorganisms transmitted by fecally contaminated water and food include bacteria, viruses, and parasites. The fecal material of infected individuals is the major source of pathogenic microorganisms in domestic wastewater; however, urine may also be a source of certain pathogenic microorganisms, such as Salmonella enterica. The concentrations and types of pathogens found in domestic wastewater will vary over time, depending on the disease incidence in the population producing the wastewater, season of the year, the amount of water being used, economic status of the population, and quality of the drinking water. If an on-site system serves a very small population (e.g., one family), it may be that no pathogens will be present in the wastewater during a part of the year. This is because, typically, disease-causing microorganisms are only present in the fecal material if an individual is actively infected with one of these microorganisms. There are some exceptions to this, such as Salmonella: approximately 1% of the population is considered to be a healthy carrier of this microorganism, and thus excretes Salmonella in their feces.

Bacteria

Bacterial pathogens have historically been the focus of waterborne disease. This is because they cause a number of diseases, such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery, which have been responsible for large epidemics (and even pandemics, in the case of cholera) all over the world. In general, many of the bacterial pathogens are relatively easy to remove through treatment processes, and, therefore, are of less concern than the other groups of pathogens in many industrialized countries. However, these pathogens are still of great concern in many of the less-industrialized countries due to the lack of adequate sanitary treatment processes in those countries.

The bacteria of most concern with respect to transmission from domestic wastewater are the enteric bacteria, which are those that infect the gastrointestinal tract of man, and are shed in the fecal material. Enteric bacteria are well adapted to the conditions present in the gastrointestinal tract, which include high organic carbon concentrations, an abundance of other essential nutrients, as well as a relatively high temperature (∼37 °C). When these organisms are introduced to the wastewater, water or soil environment, the conditions are generally very different from those in the gastrointestinal tract, in that nutrients tend to be present in low concentrations, or in forms that are difficult to metabolize. As a result, the enteric bacteria typically do not compete well with the indigenous soil or water bacteria for the scarce nutrients available. Therefore, their ability to reproduce, and even survive without reproducing, in the environment is typically limited to a few weeks to months, depending on the environmental conditions.

Typically, human fecal material contains up to 1012 bacteria per gram; the majority of these bacteria are nonpathogenic. There are, however, many different genera of bacterial pathogens that may be found in human waste. Some of the most common bacterial pathogens found in human and animal waste that are transmitted by contaminated water and food are listed in Table 2 . An infected individual may excrete very high numbers of pathogenic bacteria in her/his feces, as shown in Table 2. For example, an individual infected with Salmonella may excrete up to 100 million organisms per gram of feces.

Table 2.

Pathogens in human and animal waste that can be transmitted by water

| Organism | Disease | Numbers in feces (per gram) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria: | |||

| Campylobacter | Gastroenteritis | 10 million | |

| Leptospira | Weil disease | ||

| Pathogenic E. coli | Gastroenteritis | 100 million | |

| Salmonella | Typhoid, paratyphoid, salmonellosis | 100 million | |

| Shigella | Bacillary dysentery | 10 million | |

| Vibrio | Cholera | 10 million | |

| Yersinia | Gastroenteritis | ||

| Protozoa: | |||

| Balantidium coli | Dysentery, colonic ulceration | ||

| Cryptosporidium | Diarrhea | 100 000–1 million | |

| Cyclospora | Watery diarrhea alternating with constipation | ||

| Entamoeba histolytica | Amoebic dysentery | 100 000 | |

| Giardia lamblia | Diarrhea, malabsorption | 100 000–1 million | |

| Microsporidium | Chronic diarrhea, weight loss | ||

| Toxoplasma | Toxoplasmosis | ||

| Helminths: | |||

| Ancylostoma (hookworm) | Anemia | 100 | |

| Ascaris (roundworm) | Ascariasis | 10 000 | |

| Necator (hookworm) | Anemia | ||

| Schistosoma | Schistosomiasis | ||

| Strongyloides (threadworm) | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea | ||

| Taenia (tapeworm) | Teniasis | 10 000 | |

| Toxocara (roundworm) | Fever, abdominal pain | ||

| Trichuris (whipworm) | Diarrhea, abdominal pain | 1000 | |

| Viruses: | |||

| Adenovirus | Respiratory illness, conjuntivitis, vomiting, diarrhea | 100 billion | |

| Astrovirus | Vomiting, diarrhea | ||

| Calicivirus | Vomiting, diarrhea | ||

| Coronavirus | Vomiting, diarrhea | ||

| Enterovirus: | 10 million | ||

| Poliovirus | Paralysis, meningitis, fever | ||

| Coxsackie A | Meningitis, fever, herpangina, respiratory illness, paralysis | ||

| Coxsackie B | Myocarditis, congenital heart anomalies, rash, fever, meningitis, respiratory illness, pleurodynia | ||

| Echovirus | Meningitis, encephalitis, respiratory illness, rash, diarrhea, fever, myocarditis, endocarditis | ||

| Enterovirus 68–71 | Meningitis, encephalitis, respiratory illness, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, fever | ||

| Hepatitis A virus | Infectious hepatitis | 10 million–10 billion | |

| Hepatitis E virus | Hepatitis | ||

| Norovirus | Epidemic vomiting and diarrhea | ||

| Reovirus | Respiratory illness | ||

| Rotavirus | Diarrhea, vomiting | 100 billion | |

Parasites

The parasites constitute another group of pathogenic microorganisms that can be found in domestic wastewater. The fecal parasites that are pathogenic to humans generally can be classified into two groups: the protozoa and the helminths. Protozoans are single-celled microorganisms whose life cycles include at least one vegetative (e.g., living, feeding, and reproducing) as well as at least one resting (e.g., nonmetabolically active) stage. The resting stage of the organism is generally relatively resistant to inactivation during conventional wastewater treatment processes. Most of the intestinal protozoa are transmitted by fecally contaminated water, food, or other materials. The infective stage of the protozoans varies by organism. In the case of Cryptosporidium, the resting (i.e., oocyst) form must be ingested to initiate infection; for other protozoans, the vegetative form must be ingested for infection to occur.

The helminths are a group of multicelled parasitic worms that infect the intestines. Under the right conditions, these organisms can grow to be meters in length. The helminths are composed of several groups of worms, including the nematodes (roundworms), the trematodes (flukes), and the cestodes (tapeworms).

A list of several of the most common parasites that can be found in domestic wastewater and the diseases they cause are shown in Table 2. Similar to the bacteria, the concentrations of parasites in the fecal material of infected individuals can be very high (Table 2). For example, concentrations of Giardia and Cryptosporidium have been reported to range between 1 and 10 million cysts or oocysts per gram of feces. Although most enteric bacteria are typically excreted in the feces for only a few days or weeks, some of the parasites, such as Giardia and Entamoeba histolytica, may be excreted for several months or years.

Viruses

As discussed earlier in the text, feces always contain high concentrations of nonpathogenic bacteria. However, viruses are only present in fecal material if the individual is infected. Infection is typically inadvertent, being the result of contact with an infected individual, or ingestion of contaminated water or food. However, infection also occurs if an individual is vaccinated with the live, attenuated form of the poliovirus vaccine (OPV, oral poliovirus vaccine). Viruses can be excreted in extremely high numbers in feces. For example, the concentration of adenoviruses and rotaviruses may be as high as 100 billion particles per gram of feces. The duration of excretion of viruses varies. Noroviruses may be excreted in feces for only a few days. However, hepatitis A viruses and hepatitis E viruses may be excreted for several months. In the case of hepatitis A virus, peak excretion of virus occurs before the time that the individual exhibits symptoms of infection. Thus, an individual may be infectious and spread the infection to others before s/he even knows that s/he is infected.

There are more than 100 types of enteric viruses that can be present in domestic wastewater. A list of several of the pathogenic human enteric viruses is shown in Table 2. The diseases that can be caused by enteric viruses range widely, from asymptomatic infections to relatively mild, self-limiting diarrhea, to more severe illnesses, including respiratory illness, infectious hepatitis, paralysis, encephalitis, and myocarditis.

Indicator Microorganisms

Because feces, and therefore, domestic wastewater, may contain so many different types of enteric pathogens, it is not technically or economically feasible to test wastewater for all different types of pathogens. Therefore, for almost 100 years, the microbiological quality of water has been assessed by measuring the concentration of indicator bacteria it contains. Indicator bacteria are bacteria that are always present in fecal material. The logic in using fecal indicator bacteria is that, if they are found to be present in water, the water contains fecal material, and therefore may also contain pathogenic microorganisms. In contrast, if fecal indicators are absent, the water is considered not to be contaminated by fecal material, and therefore no fecal pathogens are present. The most common groups of indicator organisms used are the total coliform bacteria, the fecal coliform bacteria, the enterococci, and Escherichia coli.

However, in industrialized countries, many of the bacterial diseases have been controlled through the use of drinking water and wastewater treatment, including disinfection. As this has occurred, more of the focus in drinking water and wastewater treatment has been on controlling the concentrations of parasitic and viral pathogens. Unfortunately, the bacterial indicators mentioned earlier in the text do not always correlate well with the presence or behavior of the nonbacterial pathogens. Efforts are underway to identify more appropriate indicators for these pathogens.

A recent committee of the National Resources Council (NRC) of the National Academies of Science developed a series of criteria that they recommend be used when assessing the appropriateness of any indicator or group of indicators. These criteria are based on criteria developed more than 40 years ago, and separate the biological attributes of the indicators themselves from the attributes of the methods used to detect the indicators. The desirable biological attributes of indicators, as developed by the NRC, are

-

•

Correlated to health risk

-

•

Similar (or greater) survival to pathogens under environmental conditions

-

•

Similar (or greater) transport to pathogens

-

•

Present in greater numbers than pathogens

-

•

Specific to a fecal source or identifiable as to source of origin.

The desirable attributes of the methods to detect the indicators, according to the NRC, are

-

•

Specificity (independent of matrix effects)

-

•

Broad applicability

-

•

Precision

-

•

Adequate sensitivity

-

•

Rapidity of results

-

•

Quantifiable

-

•

Measures viability or infectivity

-

•

Logistical feasibility.

Regardless of the application, the most important characteristic of any indicator or indicator system is its ability to indicate possible health risk to individuals exposed to the water or food.

Pathogen Fate in Soil and Water

In order for the microorganisms in the wastewater to pose a health risk to humans, they must be transported from the on-site wastewater disposal system to a water source. In the case of a septic tank, the microorganisms must be able to survive in the tank itself, and then survive while they are being transported through the subsurface until they reach the underlying groundwater.

If a microorganism can survive in the subsurface, but is not readily transported through the soil, it is not likely that it will pose a large threat. Similarly, if the microorganism is easily transported but does not persist for very long, it may not be of much concern as a health hazard. However, if the microorganism survives in an infective form long enough to be transported through the soil and into the groundwater, this may be cause for concern if the water is used as a source of drinking water or used for irrigation of certain types of crops (e.g., vegetables eaten raw). Owing to their small size (∼25–100 nm) in the environment, enteric viruses may be expected to be transported greater distances through the subsurface than bacteria and protozoa, which are generally much larger in size. Combined with their small size, and relatively long persistence, given the high infectivity of viruses (i.e., low infectious dose, discussed later in the text), viruses are generally regarded as the most critical microorganisms with respect to microbial contamination of groundwater. However, there have been numerous instances of groundwater contamination by both bacteria and parasites as well.

In an on-site wastewater disposal system, such as a septic tank, the liquid waste passes through the soil, and removal of contaminants occurs by a variety of mechanisms. These include die-off or inactivation, adsorption, and filtration. Microorganisms have finite life spans. The length of time that they can survive in the environment varies, based on a number of factors. Viruses in the environment are metabolically inert. In other words, they are incapable of reproducing unless they are contained within an appropriate ‘host’ cell. In the cases of the viruses of concern here (discussed earlier in the text), the appropriate host is a human or primate. Therefore, once released into the environment, the number of viruses will decrease over time. Although that length of time varies from virus to virus, and under different environmental conditions, many enteric viruses can persist for several months, or even up to a year if the conditions are favorable. A list of several of the factors that affect the survival of viruses in the environment can be found in Table 3 . It should be noted that although all of these factors have been found to affect survival to some extent, the single factor that appears to be the most important is temperature. Temperature has consistently been found to be strongly correlated with the length of time that viruses survive in the environment, with longer survival associated with lower temperatures, and shorter survival with warmer temperatures.

Table 3.

Factors influencing microbial fate in the subsurface

| Factor | Influence on |

|

|---|---|---|

| Survival | Transport | |

| Temperature | Longer survival at lower temperatures | Unknown |

| Microbial activity | Variable, depending on microorganism type and environmental conditions | Unknown |

| Dissolved oxygen | Variable results have been reported | Unknown |

| Organic matter | May protect microorganism from inactivation; other studies have shown that it may reversibly retard virus infectivity | Soluble organic matter competes with microorganisms for adsorption sites on soil particles |

| Microorganism type | In general, helminths survive the longest, followed by viruses and parasites, whereas bacterial survival is generally the lowest | Larger microorganisms are removed more easily; thus, viruses have the highest potential for transport, followed by the bacteria; parasites are often too large to be transported great distances |

| Aggregation | Generally enhances survival | Retards movement, due to larger particle size |

| pH | Varies depending on microorganism, but survival tends to be best at near-neutral pH values; many enteric viruses are stable over a pH range of 3–9 | Varies, depending on isoelectric point of the microorganism; generally, low pH favors adsorption, and high pH results in desorption |

| Moisture content | Many microorgansims persist longer in soils with higher moisture content | Transport is greater under saturated than unsaturated conditions |

| Adsorption to soil | Variable results have been reported | Movement is slowed or prevented |

| Soil properties | Effects on survival are likely related to degree of adsorption to soil | Greater migration occurs in coarse-textured soils; retention is created in soils containing clay |

Source: Yates MV and Yates SR (1987) Modeling microbial fate in the subsurface environment. CRC Critical Reviews in Environmental Control 17: 307–344.

Bacteria, in contrast, are metabolically active in the environment. Thus, they are capable of growth and reproduction if the proper conditions are present. In general, enteric bacteria are not well suited to grow and survive in the environment, due to the need to compete for resources, if they are scarce. Therefore, the length of time that bacteria survive in the environment tends to be relatively short, perhaps a few days or weeks. A list of several of the factors that affect the survival of bacteria in the environment can be found in Table 3.

As mentioned earlier in the text, parasites have complex life cycles, consisting of vegetative and resting stages. The resting stages tend to be relatively resistant to environmental pressures. Protozoan parasites have been shown to survive in the environment for weeks to months. However, the ova or other resting stages of some of the helminths have been found to persist for several months to years, depending on the environmental conditions. There have been fewer studies on the factors controlling the persistence of parasites in the subsurface than of viruses, or even bacteria. However, the same general trends that have been noted for the other groups of microorganisms appear to hold true for the parasites as well (Table 3).

The transport of microorganisms through the soil and subsurface materials is dependent on the presence of water or other liquid, as the microorganisms are generally not capable of independent locomotion (or for those that are, the distances involved are much greater than what the organisms would be able to travel by themselves). Therefore, transport through the unsaturated zone can be limited. Indeed, in designing a septic tank leach field, a key consideration is the thickness of the unsaturated zone. Many regulatory authorities have established minimum vertical separation distances between the leach field and the seasonal height of the groundwater table. Once in the saturated zone, transport of microorganisms is much greater, and thus the goal is to limit the number of microorganisms that reach the saturated zone. To protect public health, many regulatory authorities have also established minimum horizontal separation distances between leach fields and drinking water wells.

The factors that reduce the number of microorganism, as they are transported in the subsurface, are filtration and adsorption. Filtration refers to the physical straining of the microorganisms as they move through the soil pores. Microorganisms that are too large to pass through the pores become trapped, and if they are not dislodged from that pore, eventually are inactivated. Therefore, the size of the microorganisms plays a major role in their ability to be transported. Viruses are smaller than the pores sizes of most soils, so they tend to undergo the greatest transport. Bacteria are larger (∼1–5 μ), so their transport is less than that of the viruses. Finally, the relatively large size of the parasites tends to limit their transport in soils. In addition to the size of the microorganism, the soil type is also critical in determining the extent of microbial transport. Soils with coarse textures, such as sands and gravels, have large pore sizes. These soils transmit water rapidly, and generally do not inhibit the transport of the microorganisms. Soils containing clays generally have very small pore openings between the individual soil grains, which limits not only water movement but also the transport of pathogens.

Adsoprtion is a different phenomenon that also controls the extent of microbial transport. Adsorption is the process whereby the microorganisms become attached to the soil particles, thus removing them from the bulk fluid, and at least temporarily, prohibiting their transport to the groundwater. Adsorption can be reversed if there is a change in environmental conditions, such as a rainfall event. There are a number of factors that control the extent of adsorption to the soil, including the pH of the environment and the nature of the subsurface material. Clay particles are especially efficient at adsorbing microorganisms as they contain electrical charges on their surfaces that attract oppositely charged particles. Some microorganisms, especially viruses, have an electrical charge, and thus are readily removed in soils that contain clays. Other factors that affect microbial transport are described in Table 3.

Disease Potential

Transmission Routes

The microorganisms associated with domestic wastewater are typically transmitted by the so-called fecal–oral route of transmission, and are often referred to as enteric pathogens. The process is initiated on ingestion of microbially contaminated water or food; the pathogen infects the intestines. This infection can result in the production of symptoms known collectively as gastroenteritis, which includes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Some pathogens can infect other organs, producing symptoms consistent with the nature of the specific infection (Table 2). For example, poliovirus infects the central nervous system, and can result in paralysis. Hepatitis A virus infects the liver, producing jaundice, fever, etc. Because the microorganisms are reproducing in the gastrointestinal tract, they are shed in the fecal material. If another individual directly ingests the fecal material, or ingests food or water that is fecally contaminated, that individual may also become infected, thereby perpetuating the cycle. Examples of the various routes of transmission of enteric pathogens from human and animal feces to humans are shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Routes of transmission of waterborne pathogens.

Burden of Disease

The World Health Organization estimates that 2.1 million people die every year from diarrheal diseases; almost 2 million of these deaths occur in children in less-industrialized countries. In addition, it is estimated that 10% of the people in less-industrialized countries are infected with parasitic worms as a result of the improper management of waste. Among the most important risk factors for these diseases are access to improved drinking water supplies and access to improved sanitation. In high-income areas, 99–100% of the population has this access, regardless of whether they live in urban or rural areas. In low-income areas, however, the situation is markedly different. It is estimated that 78% (89% urban, 73% rural) of the population has access to improved drinking water sources and 34% (53% urban, 26% rural) has access to improved sanitation.

It has been estimated that diarrhea is responsible for 11% of all deaths in the poorest 20% of all countries. The importance of access to improved drinking water supplies, improved sanitation facilities, and improved hygiene practices is illustrated by estimates of improvement in health that may result form these improvements. Simply washing hands with soap and water may reduce the transmission of Shigella and other causes of diarrhea by as much as 35%. It was estimated that the incidence of diarrhea may be reduced by 26%, and the incidence of deaths due to diarrhea may be reduced by 65% as a result of these improvements.

Although the impacts of diarrhea may be most severe in less-industrialized countries, they have a significant impact in industrialized countries as well. For example, in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that there are 2.1 million cases of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children younger than 5 years of age every year. These cases result in more than 400 000 outpatient or doctors’ office visits, and between 205 000 and 272 000 emergency room visits. Of these children, 55 000–70 000 require hospitalization, and 20–60 children die every year as a result of rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Risk of Disease

As discussed earlier in the text, the concentrations of enteric pathogens in the fecal material of infected individuals can be very high. However, a number of factors contribute to the reduction in pathogen number between the time the waste enters the on-site wastewater treatment system and the time it reaches a potable water supply. The number of microorganisms that an individual must ingest in order for that person to become infected (the ‘infectious dose’) varies greatly, depending on the microorganism. For example, ingestion of a single rotavirus particle may be sufficient to initiate an infection in an exposed individual. In contrast, it may require ingestion of millions of Salmonella bacteria to cause an infection. The minimum infectious doses of several enteric pathogens can be found in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Minimum infectious dose of selected waterborne pathogens

| Organism | Minimum infectious dose |

|---|---|

| Ascaris | 1–10 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | ∼500 |

| Cryptosporidium | 10–100 |

| E. coli O157:H7 | 10–100 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 10–100 |

| E. coli | 1–100 million |

| Giardia | 10–100 |

| Hepatitis A virus | 1–10 |

| Rotavirus | ∼1 |

| Salmonella spp. | 10 000–10 million |

| Salmonella typhi | 10 |

| Shigella spp. | 10–100 |

| Vibrio cholerae | 1000 |

It is important to realize that an infected individual may not show any signs or symptoms of infection as only a fraction of the infected individuals develop clinical illness. In the case of poliovirus infection, for example, perhaps only 1% or fewer of the infected individuals will develop clinical illness. In contrast, up to 75% of adults infected with hepatitis A virus will develop clinical illness. Regardless of whether an individual shows clinical signs and symptoms of illness, any infected individual excreting the pathogens in their feces may serve as a source of infection to others.

In a properly designed and operating system, the potential for human exposure to enteric pathogens in drinking water should be very low. However, there are still instances of waterborne disease in the United States that result from the use of potable water supplies that have been contaminated by septic tank leachate. In many cases, the outbreaks are the results of human error or overloading due to weather events. For example, in 1999, 781 individuals became ill (including 71 hospitalizations and 2 deaths) after consuming iced beverages at a fair in New York. The unchlorinated water was found to contain E. coli O157:H7, although the fecal samples from the infected individuals contained both E. coli O157:H7 and Campylobacter jejuni. It was found that there was a cross-connection between a septic system and the well. In 2001, 33 children in Maine became ill as a result of playing in a puddle that was formed from an overflowing septic tank and a large amount of rainfall. Although the specific cause of the acute gastroenteritis was not identified, high concentrations of the indicator microorganism, E. coli, were found in the water. In another case, 230 visitors to a snowmobile lodge in Wyoming during a 2-month period became ill with norovirus gastroenteritis. It was found that the wells that served the lodge, which were all located in proximity to a septic tank or outhouse, were contaminated with norovirus and fecal coliform bacteria. The wells were drilled in a fractured granite material, which was overlain by a very porous sand material. The loading rate exceeded the septic tank systems’ capacity, and, combined with the extremely porous nature of the soil material, this resulted in rapid percolation of the waste material, allowing little filtering of the contaminants to take place. A final example demonstrates the impacts of human misjudgment. In this case, 10 individuals became ill as a result of consuming water contaminated with Cryptosporidium. The well water was typically purified using a reverse osmosis system; however, when the water supply ran low, the reverse osmosis system was intentionally bypassed. The well that was used as the source of drinking water was in an area of high septic tank density.

Determining the magnitude of disease caused by the consumption of water contaminated by on-site wastewater treatment systems is extremely difficult. One reason for this is that many infected individuals never exhibit signs or symptoms of disease. Another reason is that many of the enteric pathogens cause gastroenteritis. If the illness is mild, as it is in many cases, no medical care is sought, and therefore there is no record of the illness. In the case of most of the enteric pathogens, the disease is not reportable, in any event. Compounding the issue is the fact that many of the enteric pathogens are also transmitted by contaminated foods, making it difficult to determine the source of the infection.

See also

Fate and Transport of Microbial Contaminants in Groundwater, Microbes and Water Quality in Developed Countries, Waterborne Disease Surveillance, Water-Related Diseases in the Developing World, Worldwide Regulatory Strategies and Policies for Drinking Water.

Further Reading

- ARGOSS . British Geological Survey; Wallingford: 2001. Guidelines for Assessing the Risk to Groundwater from On-Site Sanitation. [Google Scholar]

- Bitton G. Wiley; NJ: 2005. Wastewater Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell L., Bartram J., editors. Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards, and Health. IWA Publishing; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marta D., Horan N., editors. The Handbook of Water and Wastewater Microbiology. Academic Press; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. Indicators for Waterborne Pathogens. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoll O., Howard G., Chilton G., Chorus I., editors. Protecting Groundwater for Health: Managing the Quality of Drinking Water Sources. IWA Publishing; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]