Supraglottic infections comprise peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, parapharyngeal abscess and epiglottitis. Infections of the middle airways include croup (laryngotracheitis) and bacterial tracheitis. All these conditions share the potential for respiratory compromise and airway obstruction. Table 28-1 summarizes the typically affected age groups, common clinical features at presentation, and the most commonly implicated organisms. Differentiation from other airway infections is discussed in Chapter 21, Respiratory Tract Symptom Complexes (see Table 21-4).

TABLE 28-1.

Clinical Features of Infections of the Upper and Middle Airways

| Disease | Typical Age Group | Potential Initial Infection | Key Clinical Findings | Typical Organism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peritonsillar abscess | Adolescents | Pharyngotonsillitis | Sore throat, odynophagia, dysphagia, peritonsillar swelling, uvular deviation to contralateral side, muffled voice | Streptococcus pyogenes |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | <5 years of age | Pharyngitis, tonsillitis, adenitis | Sore throat, odynophagia, dysphagia, neck pain and swelling, limited neck mobility, torticollis | Streptococcus pyogenes, viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus and Neisseria species, anaerobic bacteria; often polymicrobial |

| Parapharyngeal abscess | All age groups | Pharyngitis, tonsillitis, adenitis, otitis media | Sore throat, odynophagia, dysphagia, neck pain and swelling, torticollis, deviation of the lateral wall of the oropharynx to the midline | As for retropharyngeal abscess |

| Lemierre disease (primary oropharyngeal infection; septicemia; thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein; metastatic infection at distant site(s)) | Adolescents | Pharyngitis, tonsillitis, adenitis, otitis media, mastoiditis | High-grade fever, neck pain and swelling, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, hypotension; pulmonary involvement: dyspnea, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain | Fusobacterium necrophorum |

| Epiglottitis | In Hib-unimmunized populations: children <4 years of age; in Hib-immunized populations: school age children | – | Unwell-looking, high-grade fever, stridor, drooling, muffled voice, tripod position with neck extension | Haemophilus influenzae type b |

| Croup (laryngotracheitis) | 6 months to 2 years of age | – | Inspiratory stridor, barking cough, hoarseness; symptoms typically worsen during nighttime | Parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus |

| Bacterial tracheitis | 2 to 10 years of age | – | Moderate- to high-grade fever, cough, stridor, dyspnea, retractions; rapid deterioration is common | Staphylococcus aureus |

Peritonsillar Abscess (Quinsy)

Peritonsillar abscess is the most common deep oropharyngeal infection,1 and albeit rare, usually is a complication of pharyngotonsillitis. The infection primarily affects adolescents and young adults, but can occur at any age.

Etiologic Agents

Streptococcus pyogenes is the most commonly isolated aerobic bacterium in cases with peritonsillar abscess.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Other streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae are less frequently implicated. Anaerobic bacteria, including Prevotella, Bacteroides, and Peptostreptococcus species, also are common isolates. Polymicrobial infection is not uncommon.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

The peak incidence of peritonsillar abscess is in adolescence and early adult life.1, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, although uncommon, peritonsillar abscess can occur in very young children, including infants.14, 15, 16 There is no clear gender predilection in most reports.

Peritonsillar abscess traditionally has been regarded invariably to be the result of extension of acute exudative pharyngotonsillitis. However, there is some evidence to suggest that this condition also can result from abscess formation within Weber salivary glands located in the supratonsillar fossa.17

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The patient almost invariably presents with severe sore throat and odynophagia.7, 10, 12 Difficulty with swallowing often leads to decreased oral intake, potentially resulting in dehydration.12 Symptoms may worsen and the patient may become unable to swallow saliva, leading to drooling. Fever is reported in the majority of cases but is not universal.12 Common clinical signs at initial presentation include peritonsillar swelling, muffling of the voice, cervical lymphadenopathy, trismus, and uvular deviation towards the contralateral tonsil.10, 12 Bilateral disease is very rare.11, 18

Inflammatory markers, including white blood cell (WBC) count and C-reactive protein, frequently are elevated.10, 12 In cases where there is doubt about the diagnosis, transcutaneous or intraoral ultrasound, or computed tomography (CT), can be useful for confirmation.19, 20, 21

Management

Peritonsillar abscess requires drainage, which can be achieved by needle aspiration, incision and drainage, or (quinsy) tonsillectomy.12, 13 Pus obtained during the procedure should be sent for Gram stain and routine and anaerobic culture. The choice of the intervention partly depends on the extent of patient cooperation and locally available expertise. Local practices vary widely,22 and currently there are no convincing data to suggest that one approach is superior to another.23, 24, 25, 26

There is no general consensus regarding the optimal choice of antibiotics for empiric antibiotic treatment. However, empiric therapy should provide sufficient coverage for anaerobic and β-lactamase-producing bacteria. Regimens that have been suggested include penicillin combined with metronidazole, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam, ticarcillin-clavulanate, cefoxitin, and clindamycin.7, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31

The role of adjuvant corticosteroid treatment remains controversial.10, 23, 32 Data from one randomized controlled trial in adults suggest that corticosteroids may expedite symptomatic improvement.33

The choice whether to manage a case of peritonsillar abscess as an outpatient or inpatient is made on an individual basis, taking into account the patient's age, coexisting morbidities, and the need for intravenous hydration, pain control, and airway monitoring.12

Complications and Prognosis

Only a relatively small proportion of patients require intensive care support, usually for management of airway compromise.10 The course of the illness can be complicated by contiguous invasive spread of the infection with extension to the retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal space.10, 11 Other potential complications include aspiration pneumonia and mediastinitis.

The prognosis of appropriately managed peritonsillar abscess is good. Fatal outcome is rare. Relapse or recurrence occurs in approximately 5% to 10% of cases.10, 11, 12, 18

Retropharyngeal Abscess

The retropharyngeal space extends from the base of the skull to the upper thoracic spine. The anterior border of this space is formed by the constrictor muscles of the pharynx, the lateral borders by the carotid sheaths and the posterior border by the prevertebral fascia.

Etiologic Agents

Polymicrobial infection is common; mixed aerobic and anaerobic infection occurs frequently.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 Commonly implicated aerobic bacteria include: S. pyogenes, viridans streptococci, S. aureus, as well as Haemophilus and Neisseria species. 7, 27, 34, 36, 37, 40, 41, 42, 43 Although relatively uncommon, cases due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus have been described.37, 38 Common anaerobic isolates include Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Bacteroides, and Fusobacterium species.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Retropharyngeal abscess can occur at any age, but most commonly affects children younger than 5 years of age.7, 34, 41, 44, 45, 46 In the majority of reports there is male predominance.34, 37, 38, 41, 44, 46, 47, 48 In the United States the incidence peaks during the winter and spring months.41, 42, 47 Some data suggest that the incidence of retropharyngeal abscess has increased in the U.S. over the last decade.34, 37, 39

Retropharyngeal abscess in children predominately results from infection and suppuration of the retropharyngeal chains of lymph nodes, which drain the nasopharynx, the paranasal sinuses, and the adenoids.34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42 Common primary infectious foci include pharyngitis, tonsillitis, adenitis, and less frequently sinusitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, and dental infections. Unlike in adults, local trauma and foreign body ingestion play a relatively minor role.7, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

Common presenting features include fever, sore throat, dysphagia, odynophagia, neck pain, neck swelling, limited neck mobility (particularly on extension), and torticollis.7, 34, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 45, 46, 48 Trismus and drooling are less common. The majority of patients have evidence of pharyngitis or tonsillitis and cervical lymphadenitis on examination.40, 46 In most reports the proportion of cases with symptoms indicative of airway obstruction, such as difficulty in breathing and stridor, is relatively small.37, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 46 Airway obstruction in the context of retropharyngeal abscess predominately occurs in infants and very young children.37, 38, 39

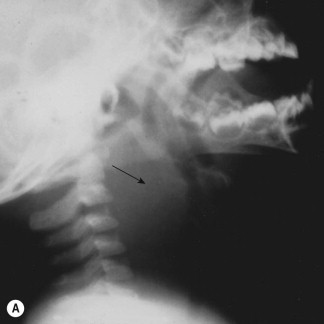

Peripheral blood leukocytosis is common.7, 34, 37, 42, 44, 46 C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) generally are elevated.46 In the majority of cases an enlargement of the retropharyngeal space/prevertebral tissue can be seen on plain lateral neck radiographs (Figure 28-1 ).34, 39, 40, 49 However, CT imaging has been shown to be the most sensitive imaging technique in cases with suspected retropharyngeal abscess, and therefore is considered the investigation of choice.39, 41, 44, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55

Figure 28-1.

(A) Lateral neck radiograph of an 18-month-old toddler with retropharyngeal abscess due to Staphylococcus aureus infection. Note marked retropharyngeal soft-tissue density (arrow) with anterior displacement of the hypopharynx and the laryngotracheal airway. Note the normal appearance of the epiglottis, glottis, and subglottic airway. (B) Chest radiograph. Note extension of the infection into the mediastinum (arrow). (C) Computed tomography scan without contrast of the upper cervical region. Note abscess in the retropharyngeal space (arrow) with anterior displacement and compression of the airway and lateral displacement of the great vessels. Bony structures are the mandible (top), hyoid bone, and the cervical vertebrae.

Management

There is no consensus regarding the optimal empiric antibiotic treatment. Penicillin or ampicillin alone provide insufficient coverage, as S. aureus and mixed infections are common, and β-lactamase-producing organisms are isolated in a significant proportion of cases. Empiric antibiotic regimens include: a combination of a second- or third-generation cephalosporin and clindamycin; a combination of a second- or third-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole, amoxicillin-clavulanate; ampicillin-sulbactam, or piperacillin-tazobactam.34, 41, 42, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59 Some authors have suggested that clindamycin alone may be sufficient.36, 48 Local patterns of susceptibility of S. aureus as well as clinical state of the patient should be taken into account. (A combination of antibiotics that includes clindamycin or vancomycin may need to be considered.)

The role of surgical drainage remains controversial.34, 37, 42, 44, 46, 54, 60 Patients with significant respiratory distress require urgent airway management and surgical drainage. However, there is debate whether a trial of conservative management with intravenous antibiotics for a 24- to 48-hour period in conjunction with close monitoring is appropriate for patients who are stable and have no respiratory distress.34, 40, 41, 42, 44 The reported success rates with conservative management alone vary considerably between different studies, and there are no data from randomized trials.34, 40, 41, 42, 44, 46, 48 Surgical drainage usually is performed via the transoral approach, and less commonly via the transcervical route.37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 48, 53, 54

Complications and Prognosis

Potential complications include internal jugular vein thrombosis, mycotic aneurysm of the carotid artery, aspiration pneumonia, mediastinitis, and sepsis, although these are rare overall.37, 38, 39, 41, 44, 45 Only a small proportion of patients require repeated surgical intervention.39, 41 The vast majority of patients have an uncomplicated course and can be discharged on oral antibiotics within a few days.37, 38 Fatal outcomes are rare in recent studies.

Parapharyngeal Abscess

The lateral pharyngeal space (or parapharyngeal space) is shaped like an inverted cone extending from the base of the skull to the hyoid bone, bounded medially by the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and laterally by the internal pterygoid muscle.61 The lateral pharyngeal space contains the following anatomical structures: the internal carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, the cranial nerves IX–XII, the sympathetic chain, and lymph nodes. This space is separated from the retropharyngeal space only by the alar fascia, which provides little barrier against the spread of infection.61 Consequently, simultaneous infection of both compartments is common, and some authors believe that a distinction between parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscess is clinically not meaningful.42, 58, 61, 62, 63

Etiologic Agents, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis

The spectrum and frequency of causative organisms are similar to those reported in retropharyngeal abscess.27, 64 Studies on deep neck space infections in children suggest that parapharyngeal abscesses are less common than retropharyngeal abscesses.7, 28, 41, 46 In contrast to retropharyngeal abscess, parapharyngeal abscess occurs in all age groups without predilection for younger children.45, 65 Parapharyngeal abscess is thought primarily to result from infection and subsequent suppuration of lymph nodes in the lateral pharyngeal space, which are part of the lymphatic drainage of the nasopharynx and the middle ear.65, 66, 67, 68 In a large proportion of cases there is a history of preceding pharyngitis or tonsillitis.

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

The clinical features of parapharyngeal abscess closely resemble those associated with retropharyngeal abscess.61 Fever and neck swelling are common features; dysphagia, odynophagia, torticollis, or trismus also can be present.45, 58, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 67, 68, 69, 70 A key distinguishing feature from retropharyngeal abscess is the frequent finding on oral inspection of deviation of the lateral wall of the oropharynx to the midline.65, 69, 70, 71

Peripheral blood leukocytosis and CRP elevation are common.59, 66 Contrast-enhanced CT is considered to be the imaging modality of choice in cases with suspected parapharyngeal abscess.41, 45, 46, 58, 61, 62, 69, 72 Unlike in retrophayngeal abscess, plain lateral neck radiographs are not useful.41

Management, Complications, and Prognosis

The management of parapharyngeal abscess is similar to that of retropharyngeal abscess. There is ongoing controversy among experts about whether surgery is mandatory in all patients.42, 46, 58, 59, 62, 63, 65, 67, 68, 70 Traditionally, an external cervical approach has been used for the drainage of parapharyngeal abscesses.7, 53, 73 More recently, transoral drainage has been reported to be safe and effective in selected cases with abscess location medial to the great vessels.61, 63, 68, 69, 73 The transoral approach has cosmetic advantages, and the intraoperative time generally is shorter.73

Potential complications comprise internal jugular vein thrombosis, erosion of the carotid artery, airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, pleural empyema, mediastinitis, pericarditis, and septic shock.7, 45, 62, 64, 65, 68, 74, 75 Fatal outcome and long-term sequelae are rare.28, 62, 65

Lemierre disease

The first description of this clinical syndrome was published in 1900 by Courmont and Cade,76 followed by a report by Schottmuller in 1918.77 However, the syndrome, also referred to as “necrobacillosis,” is named in honor of André Lemierre, who described a series of 20 cases of “postanginal septicemia” in 1920.78 Classically, Lemierre disease is characterized by the following features: (1) primary infection of the oropharynx; (2) blood-culture confirmed septicemia; (3) evidence of thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein; and (4) metastatic infection at one or more distant sites.79

Etiologic Agents

Fusobacterium necrophorum is by far the most commonly implicated etiologic agent.79, 80, 81, 82 F. necrophorum is an obligate anaerobic gram-negative bacillus that is part of the normal flora of the oral cavity and the gastrointestinal and female genital tract. Most strains are susceptible to second- and third-generation cephalosporins, clindamycin, and metronidazole; a significant proportion of clinical isolates produce β-lactamase.83, 84, 85 Other causative bacteria described in association with Lemierre syndrome include other Fusobacterium species, Bacteroides and Prevotella species, streptococci (mainly non-group A), and infrequently staphylococci.79, 80, 82, 86, 87 Mixed infections are not uncommon.81, 87

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Despite the absence of solid epidemiologic data, most experts agree that the incidence of the disease has declined considerably during the antibiotic era. Lemierre syndrome currently is an uncommon disease, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 per million persons per year.88 However, there are some data suggesting that the incidence may have increased in recent years, potentially as a result of more judicious antibiotic prescribing practices for cases of upper respiratory tract infection.89 The disease typically affects teenagers and young adults,79, 80, 86, 87, 89, 90 although a few cases in infancy have also been described.83, 91 There appears to be some male predominance.79, 92 The vast majority of cases have no predisposing illness.

In the majority of cases the disease process begins with a primary focus of infection in the oropharynx (e.g., palatine tonsils or peritonsillar tissue). Other infections in the head and neck area, including sinusitis, otitis, mastoiditis, parotitis, and odontogenic infections, are less common sources.79, 83, 86, 87, 88, 91, 92, 93 The infection subsequently spreads to the lateral pharyngeal space (or parapharyngeal space). Further progression results in infectious thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, which in turn results in septic pulmonary emboli and metastatic infection at other distant sites. The lungs are by far the most commonly involved secondary site, followed by joint and soft-tissue infections.79, 80, 87, 92 Other manifestations, such as skin infection, osteomyelitis, liver abscess, splenic abscess, and meningitis, are relatively rare.79, 83, 92, 94, 95, 96, 97

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

The presenting features depend partly on the primary site of infection. Most cases come to medical attention within 7 days of onset of the primary infection.79 In patients with an oropharyngeal source, inspection may reveal exudative tonsillitis, hyperemia, or greyish pseudomembranes. Importantly, an unremarkable oropharyngeal appearance at the time of septicemia does not rule out Lemierre syndrome.79, 98 Patients with otitis media or mastoiditis as the primary focus can present with otorrhea or postauricular fluctuation.83, 99 The majority of patients have high fever (>39.5°C), although fever can be absent. Neck swelling and tenderness is present in the majority of cases. Other symptoms and signs that may be present include trismus, dysphagia, dyspnea, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, nausea and vomiting, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and hypotension. Severe shock and renal failure are relatively uncommon, despite the septicemic state.79, 86 Auscultation and percussion of the chest may reveal crepitus and evidence of pleural effusions in cases with pulmonary involvement.

Inflammatory markers, including WBC count, CRP, and ESR, often are markedly elevated.80, 87, 89, 91, 92, 100, 101, 102, 103 Thrombocytopenia occurs in approximately a quarter of patients.100 Serum-hepatic enzymes and bilirubin are not infrequently elevated.79, 87 Blood cultures typically are positive, but can be sterile in patients who have taken antibiotics prior to presentation. Contrast-enhanced CT of the neck is considered to be the most useful investigation. Possible CT findings include distended neck veins, intraluminal filling defects, and soft tissue swelling.87, 91, 101, 103, 104 Doppler ultrasonography or MRI are further useful imaging modalities in this setting. Chest radiographs and chest CT may reveal pulmonary infiltrates, pulmonary cavitation, or pleural effusions (Figure 28-2 ).

Figure 28-2.

(A) Chest computed tomography scan of a 16-year-old patient with Lemierre syndrome with marked pulmonary involvement showing a large left sided pneumothorax (arrow) and adjacent empyema. (B) Chest computed tomography scan of the same patient showing widespread bilateral pulmonary consolidation and nodular foci. Note the central cavitation in the lesion marked by the arrow. (C) Coronal magnetic resonance image of the hip region in the same patient, who also developed septic arthritis of the left hip joint and abscess formation in the adjacent muscles. Note the synovial enhancement and joint effusion (small arrow) and the adjacent fluid collection (large arrow), which extends anteriorly between the iliopsoas, the rectus femoris medially, and the gluteus muscles laterally.

Management

Antibiotic treatment is the mainstay of therapy. Empiric regimens commonly suggested by experts include: high-dose penicillin in combination with metronidazole; clindamycin; ticarcillin-clavulanate, and ampicillin-sulbactam.82, 87, 89, 98, 100, 101, 102, 105 Due to the endovascular nature of the infection, prolonged intravenous therapy for several weeks is required. Surgical debridement of necrotic tissues, and drainage of abscesses or empyemas often is required in conjunction with medical therapy. Ligation or resection of the internal jugular vein was a common therapeutic intervention in the pre-antibiotic era. However, this is rarely necessary now, and should be restricted to unstable patients who fail to respond to conservative therapy.89, 100, 101, 106 The role of routine anticoagulation therapy in Lemierre syndrome continues to be controversial.81, 86, 87, 89, 99, 100, 106

Complications and Prognosis

Metastatic infections can cause complications depending on their location. Pleural effusions, empyema, lung abscesses, and pulmonary cavitation are not uncommon manifestations. Pneumatocele and pneumothorax also have been described. Pyogenic arthritis typically affects larger joints, such as the shoulder, elbow, and hip joints (Figure 28-2).79, 92 Renal involvement can be associated with proteinuria or hematuria.

In the pre-antibiotic era the prognosis was poor, with fatality rates as high as 90% in some historical reports.78, 93 Recent reviews of the literature suggest that fatal outcome is now uncommon, and likely to be between 5% and 10%.79, 80

Acute Epiglottitis (Supraglottitis)

Since introduction of effective vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), and their inclusion in routine childhood immunization programs in many countries, the incidence of invasive Hib disease has decreased dramatically, and epiglottitis has become a rare disease.107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 Necrotizing epiglottitis is an extremely rare variant, which has predominately been reported in immunocompromised patients.119

Etiologic Agents

Haemophilus influenzae type b accounted for approximately 75% to 90% of epiglottitis cases in the pre-Hib vaccination era.108, 115, 120 Since the introduction of Hib conjugate vaccines, the proportion of cases caused by Hib has declined considerably, although cases related to vaccination failure have continued to be reported.108, 111, 115, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124 Other organisms implicated in epiglottitis are S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, nontypable Haemophilus influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, Pseudomonas species, Klebsiella species, and Moraxella catarrhalis.108, 115, 120, 125, 126, 127, 128

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

In the pre-Hib vaccination era the incidence of epiglottitis peaked in early childhood, typically affecting children younger than 4 years of age.120, 125 Since the introduction of universal Hib vaccination, the peak incidence has shifted towards an older age group, with a simultaneous increase in the proportion of adult cases.108, 114, 118, 124, 125, 128, 129, 130 Many studies show no gender predominance, while others report some male predominance.111, 120, 130, 131, 132 In temperate climates, there is little seasonal variation in the incidence.118, 130, 131, 132, 133

Acute epiglottitis is a localized, invasive bacterial infection of the supraglottic area, comprising the epiglottis, the arytenoid cartilages, aryepiglottic folds, and false vocal cords. Inflammation results in airway edema and narrowing, which leads to airway obstruction manifesting as stridor and respiratory distress. The localized infection can evolve into phlegmon and abscess formation. Bacteremia is common in cases caused by Hib, but dissemination to distant sites (e.g., causing arthritis or meningitis) is rare.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Children with epiglottitis typically look systemically unwell, and have high fever and stridor.111, 125, 132 Aphonia and a muffled (“hot potato”) voice are common features.118, 125 Odynophagia is very common, and drooling frequently is observed. The majority of patients assume an upright position (e.g., “tripod position”) with extension of the neck.134 Cervical lymphadenopathy is also a common feature.125

Peripheral blood leukocytosis is present in the majority of cases.118, 125, 128, 133 Lateral neck radiographs, demonstrating epiglottic enlargement or a classic “thumb sign,” have relatively high sensitivity, but should only be attempted in stable patients in a safe environment (Figure 28-3 ).121, 125

Figure 28-3.

Lateral neck radiograph of a 4-year-old child with acute epiglottitis. Note characteristically distended hypopharynx and “thumbprint” edematous epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds (arrow).

Management

Effective airway management is the most critical component of management of epiglottitis. Causing upset to the child and attempts at oral/pharyngeal inspection can potentially result in complete airway obstruction. Nebulized epinephrine (adrenaline) may provide some transient improvement in patients with respiratory distress, but also can cause agitation and precipitate respiratory obstruction. Unstable patients should be urgently intubated via direct laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy in a controlled setting (i.e., operating room or intensive care unit). Although rarely required, facilities to perform a tracheostomy must be available in case intubation attempts fail.111, 118, 125, 130 There continues to be controversy about whether cases at the mild end of the disease spectrum without significant respiratory distress can be managed safely without intubation while being closely monitored.118, 125, 135

Blood cultures and throat/epiglottic swabs (in intubated cases) should be obtained for culture and susceptibility testing. Empiric antibiotic therapy, such as a third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin-sulbactam, should be commenced promptly.108, 111, 120, 123, 135, 136 The routine use of corticosteroids, intended to reduce airway edema, remains controversial; there are no randomized controlled trial data available at present;118, 128, 135 however, uncontrolled studies have not shown a clear benefit regarding the need for intubation, duration of ventilation, or duration of hospital stay.125, 128, 133 In cases with confirmed Hib epiglottitis, prophylaxis with rifampin should be considered for household contacts according to American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations.137

Complications and Prognosis

Potential complications include complete airway obstruction and cardiac arrest, epiglottic abscess, deep neck infection, pneumonia, and seizures.111, 118, 120, 125

Most patients require only a short period of intubation and ventilation, and can be extubated within 24 to 72 hours.111, 118, 120, 132 Fatal outcome is relatively rare (less than 5%) in settings where good intensive care support is available.118, 120, 125, 130

Croup (Laryngotracheitis)

Viral croup is the commonest cause of infectious upper-airway obstruction in young children. Some authors prefer to divide croup into spasmodic croup and laryngotracheitis (also commonly referred to as laryngotracheobronchitis).138 However, in a clinical setting this distinction is not particularly meaningful, and croup is therefore used as a summative term in this chapter.

Etiologic Agents and Epidemiology

Parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3 are the most common causative agents of croup, accounting for 50% to 80% of cases, followed by influenza A, influenza B, and respiratory syncytial virus.139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144 Other, less common etiologic agents include adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, coxsackieviruses, and echoviruses.139, 140, 144, 145 More recent studies have documented human metapneumovirus, human bocavirus, and human coronavirus NL63 as further causative agents of croup.145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152 There are some data suggesting that the clinical course of croup caused by influenza virus is more severe than croup caused by parainfluenza virus.139

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Croup is a very common disease; one study from Seattle estimated the annual incidence in children under the age of 6 years to be as high as 7 per 1000 children.144 The incidence of croup is highest in children aged 6 months to 2 years.140, 142, 143, 144 Typical croup symptoms are rarely observed in children older than 6 years of age, likely owing to the increase in airway diameter.143 The incidence is higher in boys.138, 139, 140, 142, 153 In temperate climates the incidence typically peaks in late autumn and winter.140, 142, 144, 153

Inflammatory edema and mucus production result in airway narrowing in the subglottic region, resulting in stridor.134, 138, 154, 155 Inflammation of the vocal cords results in hoarseness, and sometimes aphonia.

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

The typical features of croup are inspiratory stridor, a barking cough, and hoarseness. The symptoms often start abruptly, and typically worsen during the nighttime.156 Nonspecific coryzal symptoms frequently precede the illness. The majority of patients have low-grade or moderate fever.141, 142 Less than 3% of cases presenting in a primary care setting require hospitalization.141, 142 (Infectious and noninfectious causes and clinical features of upper-airway obstruction, including croup, are delineated in Chapter 21, Respiratory Tract Symptom Complexes, and highlighted in Tables 21-3, 21-4, and 21-5Table 21-3Table 21-4Table 21-5.) Noninfectious differential diagnosis includes foreign body aspiration, vocal cord dysfunction, laryngeal web, allergic or hypocalcemic laryngospasm, subglottic stenosis (e.g., after prolonged intubation), tracheomalacia, H-type tracheoesophageal fistula, gastroesophageal reflux, and vascular ring.138, 156, 157, 158, 159 Laryngeal diphtheria, now a very rare but potentially life-threatening infection, can present as severe croup.156, 160, 161

The diagnosis of croup primarily is made on clinical grounds. Airway or chest radiographs are not indicated in cases with uncomplicated croup.156, 162, 163 However, radiologic investigation can be useful if an alternative diagnosis is suspected. Similarly, laboratory tests, including rapid antigen tests and viral cultures, are not indicated routinely as they rarely help in case management.156

Management

Treatment with mist or humidified air has been a key component of croup management for much of the twentieth century.138 However, there are few published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effectiveness of humidified air.164, 165, 166, 167 All of these studies have been conducted in a hospital environment, and there are no published data on the effectiveness of warm humidified air in the home environment – a measure frequently recommended to parents.168 A recent Cochrane review that included pooled data from three RCTs found that there was some, but statistically nonsignificant, improvement in the croup severity score of patients receiving humidified air compared with patients remaining in room air during the first hour of treatment; there was no difference between treatment groups for other outcome measures.168

Treatment with corticosteroids is indicated routinely.138 A recent Cochrane review, which included 31 RCTs, showed that corticosteroid treatment was associated with significant improvement in croup severity score at 6 and 12 hours compared with placebo.169 In addition, corticosteroid treatment was associated with a shorter duration of stay in the emergency department or hospital, fewer admissions, and fewer return visits. However, a variety of corticosteroids (dexamethasone, budesonide, methyl-prednisolone, and fluticasone), different routes of administration (orally, intramuscular, inhaled) and doses were used in the trials included. Most experts currently recommend the use of either oral or intramuscular dexamethasone (at a dose of 0.6 mg/kg) or nebulized budesonide (at a dose of 2 mg).138, 162, 170, 171, 172 It currently remains unclear whether repeated doses over the first 48 hours improve outcome.

Multiple studies have shown that nebulized epinephrine (adrenaline) is effective for achieving symptomatic improvement in children with moderate to severe croup.173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178 In addition, there are data to suggest that the use of nebulized epinephrine has resulted in a considerable reduction in the need for intubation or tracheostomy.179 The drug can be administered as racemic epinephrine (2.25%; 0.5 mL in 2.5 mL of saline) or L-epinephrine (1 : 1000 solution; 5 mL). The treatment is safe and side effects, such as pallor and tachycardia, generally are mild and transient.180

In children with moderate croup (i.e., with stridor and chest wall indrawing at rest) who fail to improve sufficiently within 4 to 6 hours of administration of a corticosteroid, hospitalization should be considered. Children with severe croup should receive a dose of a corticosteroid and be treated with nebulized epinephrine; repeated administration of nebulized epinephrine may be necessary. Intensive care support should be considered if there is insufficient response. It is important to remember that the effect of nebulized epinephrine only lasts for 1 to 2 hours.173 Once the drug effect wears off clinical symptoms can return to baseline, or even become more severe (so-called “rebound effect”).170

Children with oxygen saturation below 92% in room air should be given supplemental oxygen. Several reports have described the use of heliox in croup, with some promising results.181, 182, 183 However, a recent Cochrane review concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence to support its use in this setting.184 The use of antitussive and decongestant agents is not recommended.138, 170 Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated, unless clinical features or laboratory results indicate secondary bacterial infection.138, 157, 170 In cases of severe croup caused by influenza A or B virus, treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor should be considered, although currently there are insufficient efficacy data in this setting.138, 185, 186, 187

Complications and Prognosis

Only a small proportion of cases with croup require intubation and ventilation.139, 140 Contiguous spread of the viral infection is not uncommon, which can result in otitis media, bronchiolitis, or pneumonia. Bacterial superinfection can lead to bacterial tracheitis (see below) or bronchopneumonia.

The prognosis of uncomplicated croup is very good. Symptoms largely resolve within 48 to 72 hours in the majority of patients.156 Fatal outcome is very rare.

Acute Laryngitis

Isolated, acute laryngitis is primarily a disease described in adolescents and adults.

Etiologic Agents

Acute laryngitis is most commonly caused by viral infections; the spectrum of causative viral agents is very similar to that described in croup.188, 189, 190, 191, 192 Bacterial organisms that have been implicated in acute laryngitis include S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis.193, 194, 195

Clinical Manifestations and Management

The key features of acute laryngitis are a change in the normal pitch of the voice and hoarseness, which typically lasts for 3 to 7 days. Coexistence of nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection symptoms, such as coryza, sore throat, and cough, is common.

Acute laryngitis in previously healthy individuals is a self-limiting disease. Given that the majority of cases are due to viral infection, treatment with antibiotics is not routinely indicated. Notably, a recent Cochrane review on this topic, which included two RCTs evaluating penicillin V and erythromycin versus placebo, concluded that routine antibiotic treatment is of no proven benefit.196

Bacterial Tracheitis

The term “bacterial tracheitis” was first used in a publication by Jones et al. in 1979.197 However, earlier reports describe cases of “laryngotracheobronchitis” that closely resemble descriptions of bacterial tracheitis, suggesting that this entity existed previously.198, 199

Etiologic Agents

S. aureus is by far the most common causative organism.114, 200, 201, 202 Other bacteria commonly implicated in bacterial tracheitis are S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis. Cases attributed to a variety of other bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Prevotella, and Bacteroides species, also have been reported in the literature, although these appear to be uncommon.200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Bacterial tracheitis is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence below 0.1/100,000 children per year in the United Kingdom and in Australia.201 No incidence data have been published for other countries. Some data suggest that the incidence peaks during autumn and winter.201 Bacterial tracheitis predominately affects young children, although a few adult cases have been described.208, 209, 210

The pathogenesis of bacterial tracheitis remains unclear. It has been postulated that viral infection of the upper respiratory tract may facilitate secondary bacterial infection and invasion of the airways, resulting in inflammation and edema, which ultimately leads to narrowing of the trachea.200 This concept is supported by the fact that the peak incidence of bacterial tracheitis coincides with the peak season for viral respiratory pathogens. In one large case series, coinfection with influenza virus was identified in almost one-third of cases.202 Coinfection with parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenovirus has been described in other reports.114, 201, 204, 211

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

The majority of patients with bacterial tracheitis report prodromal symptoms suggestive of a minor upper respiratory tract infection, which typically are present for 2 to 5 days prior to the onset of stridor. Once stridor and dyspnea develop, patients often deteriorate rapidly, frequently requiring intubation to overcome increasing upper-airway obstruction within the first 24 hours.197, 201, 212, 213 Other common features at presentation include fever (often moderate to high grade), hoarse voice or aphonia, cough, as well as intercostal and subcostal retractions. Drooling is uncommon. Most cases show little or no response to nebulized epinephrine.214

The main differential diagnoses are epiglottis and viral croup. Unlike cases of bacterial tracheitis, children with epiglottitis typically refuse to speak, have drooling, and adopt an upright position with extension of the neck. Cases with croup typically have only low-grade fever, do not appear toxic, and generally respond to nebulized epinephrine.

Inflammatory markers, such as CRP and WBC count, are elevated in the majority of cases at presentation.201, 214 Radiographs may demonstrate narrowing of the tracheal air shadow and tracheal membranes, although these are not universal findings (Figure 28-4 ).204, 211 Coexisting pulmonary changes, including infiltrates and atelectases, are relatively common.201, 214, 215, 216, 217 Direct visualization of the airways reveals an unremarkable or only mildly inflamed epiglottis, but marked subglottic inflammation, edema of the tracheal mucosa, and copious purulent endotracheal secretions.197, 214 Endotracheal aspirates should be obtained and sent for bacterial culture and susceptibility testing. Blood cultures are positive infrequently.

Figure 28-4.

(A) Lateral neck radiograph of a 22-month-old boy with bacterial tracheitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus showing subglottic haziness (similar to croup). (B) Endoscopic view of the trachea shows mucosal denudation, intraluminal debris, and purulent laryngotracheal secretions.

Management

Proactive airway management is critical in bacterial tracheitis, in order to prevent complete airway obstruction and consequent respiratory arrest. In most larger published case series, 80% to 100% of the cases required intubation or tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation.200 Intubation of these cases generally is challenging, and usually requires the use of an endotracheal tube of considerably smaller diameter than would be expected based on the patient's age. It is important that the capability to conduct a tracheostomy is available, in case conventional intubation attempts fail.

There is no consensus among experts regarding the most appropriate empiric antibiotic treatment, although there is agreement that this must include effective anti-staphylococcal coverage. Based on published data on the frequency and range of causative organisms, a combination of a third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., cefotaxime) and a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (e.g., cloxacillin or nafcillin) intravenously is a suitable choice. In areas where community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections are common, vancomycin should replace the latter. Although good quality evidence is lacking, many centers use systemic corticosteroids in the first few days of the illness with the intention to reduce airway edema.

The majority of patients require ventilatory support for a relatively short period of time, typically for 2 to 5 days, unless complications occur. The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment is unknown, but it generally is recommended for a minimum of 10 days.

Complications and Prognosis

Complications of bacterial tracheitis include pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, hypotension, and cardiorespiratory arrest.204, 211, 214, 218 In addition, a few cases with toxic shock syndrome have been described.211, 213, 219 Neurologic sequelae are common in patients who experience cardiorespiratory arrest. Subglottic stenosis and subglottic polyps are further potential long-term sequelae, albeit rare.211, 220

Bacterial tracheitis is a potentially life-threatening condition, with some of the earlier publications reporting case fatalities in excess of 20%.211, 218 However, fatal outcomes are uncommon in reports published during the last decade, likely reflecting improvements in recognition and intensive care support.114, 201, 202

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis predominately occurs in adolescents and adults. Data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey suggest that approximately 5% of all adults experience one or more episodes of bronchitis per year.221 The incidence peaks in autumn and winter.222

Etiologic Agents

Most cases of bronchitis are nonbacterial in nature. However, in a large proportion of patients no causative organism can be identified. Viral infections appear to account for the majority of cases.223, 224 Viruses commonly implicated in acute bronchitis include influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, and human metapneumovirus.223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228 Infection due to bacterial organisms, including Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, is less common.223, 224, 225

Clinical Manifestations and Management

The illness typically begins with nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection symptoms, which usually last for a few days. This is followed by a second phase characterized by persistent cough, frequently with sputum production or wheezing, which typically lasts for 1 to 3 weeks.222, 223

Antibiotic therapy is not routinely indicated in previously healthy individuals with acute bronchitis.222, 229 A recent Cochrane review that included nine RCTs showed that antibiotic treatment on average reduces the duration of cough only by less than one day compared with placebo; simultaneously adverse effects were significantly more common in the antibiotic-treated patients.230 Recent guidelines for management of acute bronchitis by the American College of Physicians and the American College of Chest Physicians have discouraged the routine use of antibiotics, inhaled bronchodilators, and mucolytic agents.231, 232 Nevertheless, patients diagnosed with pertussis should receive antibiotics, primarily to limit transmission.222

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the use of figures and legends (Figure 28-1, Figure 28-3, Figure 28-4) contributed by Richard H. Schwartz from the 3rd edition.

References

- 1.Schweinfurth JM. Demographics of pediatric head and neck infections in a tertiary care hospital. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:887–889. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000217526.19167.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brook I, Frazier EH, Thompson DH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:289–292. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavriel H, Lazarovitch T, Pomortsev A, Eviatar E. Variations in the microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:27–31. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jousimies-Somer H, Savolainen S, Makitie A, Ylikoski J. Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl 4):S292–S298. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_4.s292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snow DG, Campbell JB, Morgan DW. The microbiology of peritonsillar sepsis. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:553–555. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100116585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchelmore IJ, Prior AJ, Montgomery PQ, Tabaqchali S. Microbiological features and pathogenesis of peritonsillar abscesses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:870–877. doi: 10.1007/BF01691493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodds B, Maniglia AJ. Peritonsillar and neck abscesses in the pediatric age group. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:956–959. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segal N, El-Saied S, Puterman M. Peritonsillar abscess in children in the southern district of Israel. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1148–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunnergren O, Swanberg J, Molstad S. Incidence, microbiology and clinical history of peritonsillar abscesses. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:752–755. doi: 10.1080/00365540802040562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millar KR, Johnson DW, Drummond D, Kellner JD. Suspected peritonsillar abscess in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:431–438. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000280525.44515.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marom T, Cinamon U, Itskoviz D, Roth Y. Changing trends of peritonsillar abscess. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schraff S, McGinn JD, Derkay CS. Peritonsillar abscess in children: a 10-year review of diagnosis and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinberg E, Brodsky L, Stanievich J, Volk M. Needle aspiration of peritonsillar abscess in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:169–172. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140051009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhtar MJ, Shinefield HR. Staphylococcus aureus peritonsillar abscess in an 11-week old infant. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:78–80. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100132785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brondbo K, Hoie T, Aalokken M. Peritonsillar abscess in a 2 1/2-month-old infant. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zohar S, Golz A, Abraham S. Peritonsillar abscess in an infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;15:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(88)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passy V. Pathogenesis of peritonsillar abscess. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:185–190. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong YK, Goh YH, Lee YL. Peritonsillar infections: local experience. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott PM, Loftus WK, Kew J. Diagnosis of peritonsillar infections: a prospective study of ultrasound, computerized tomography and clinical diagnosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:229–232. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyon M, Blaivas M. Intraoral ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of suspected peritonsillar abscess in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:85–88. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miziara ID, Koishi HU, Zonato AI. The use of ultrasound evaluation in the diagnosis of peritonsillar abscess. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2001;122:201–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehanna HM, Al-Bahnasawi L, White A. National audit of the management of peritonsillar abscess. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:545–548. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.923.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson RF, Stewart MG, Wright CC. An evidence-based review of the treatment of peritonsillar abscess. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:332–343. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spires JR, Owens JJ, Woodson GE, Miller RH. Treatment of peritonsillar abscess. A prospective study of aspiration vs incision and drainage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:984–986. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860090082025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stringer SP, Schaefer SD, Close LG. A randomized trial for outpatient management of peritonsillar abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:296–298. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860150078019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maharaj D, Rajah V, Hemsley S. Management of peritonsillar abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:743–745. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100117189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brook I. Microbiology and management of peritonsillar, retropharyngeal, and parapharyngeal abscesses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:1545–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungkanont K, Yellon RF, Weissman JL. Head and neck space infections in infants and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:375–382. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galioto NJ. Peritonsillar abscess. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prior A, Montgomery P, Mitchelmore I, Tabaqchali S. The microbiology and antibiotic treatment of peritonsillar abscesses. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:219–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Yaghchi C, Cruise A, Kapoor K. Out-patient management of patients with a peritonsillar abscess. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:52–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2007.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herzon FS, Martin AD. Medical and surgical treatment of peritonsillar, retropharyngeal, and parapharyngeal abscesses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2006;8:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozbek C, Aygenc E, Tuna EU. Use of steroids in the treatment of peritonsillar abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:439–442. doi: 10.1258/002221504323219563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdel-Haq NM, Harahsheh A, Asmar BL. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: the emerging role of group A beta hemolytic streptococcus. South Med J. 2006;99:927–931. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000224746.39728.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brook I. Microbiology of retropharyngeal abscesses in children. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:202–204. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460020092034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asmar BI. Bacteriology of retropharyngeal abscess in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page NC, Bauer EM, Lieu JE. Clinical features and treatment of retropharyngeal abscess in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elsherif AM, Park AH, Alder SC. Indicators of a more complicated clinical course for pediatric patients with retropharyngeal abscess. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirse DJ, Roberson DW. Surgical management of retropharyngeal space infections in children. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1413–1422. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig FW, Schunk JE. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: clinical presentation, utility of imaging, and current management. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1394–1398. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daya H, Lo S, Papsin BC. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal infections in children: the Toronto experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnston D, Schmidt R, Barth P. Parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal infections in children: argument for a trial of medical therapy and intraoral drainage for medical treatment failures. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:761–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coticchia JM, Getnick GS, Yun RD, Arnold JE. Age-, site-, and time-specific differences in pediatric deep neck abscesses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:201–207. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SS, Schwartz RH, Bahadori RS. Retropharyngeal abscess: epiglottitis of the new millennium. J Pediatr. 2001;138:435–437. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang L, Chi H, Chiu NC. Deep neck infections in different age groups of children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43:47–52. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grisaru-Soen G, Komisar O, Aizenstein O. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess in children: epidemiology, clinical features and treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1016–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lander L, Lu S, Shah RK. Pediatric retropharyngeal abscesses: a national perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:1837–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Sabah B, Bin Salleen H, Hagr A. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: 10-year study. J Otolaryngol. 2004;33:352–355. doi: 10.2310/7070.2004.03077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boucher C, Dorion D, Fisch C. Retropharyngeal abscesses: a clinical and radiologic correlation. J Otolaryngol. 1999;28:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Endicott JN, Nelson RJ, Saraceno CA. Diagnosis and management decisions in infections of the deep fascial spaces of the head and neck utilizing computerized tomography. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:630–633. doi: 10.1002/lary.1982.92.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holt GR, McManus K, Newman RK. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of deep-neck infections. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:693–696. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790590015005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stone ME, Walner DL, Koch BL. Correlation between computed tomography and surgical findings in retropharyngeal inflammatory processes in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(99)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osborn TM, Assael LA, Bell RB. Deep space neck infection: principles of surgical management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lalakea M, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal abscess management in children: current practices. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:398–405. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freling N, Roele E, Schaefer-Prokop C, Fokkens W. Prediction of deep neck abscesses by contrast-enhanced computerized tomography in 76 clinically suspect consecutive patients. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1745–1752. doi: 10.1002/lary.20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gorbach SL. Piperacillin/tazobactam in the treatment of polymicrobial infections. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20(Suppl 3):S27–S34. doi: 10.1007/BF01745248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Philpott CM, Selvadurai D, Banerjee AR. Paediatric retropharyngeal abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:919–926. doi: 10.1258/0022215042790538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Broughton RA. Nonsurgical management of deep neck infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:14–18. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelaz AC, Allende AV, Llorente Pendas JL, Nieto CS. Conservative treatment of retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess in children. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:1178–1181. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181acdc45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plaza Mayor G, Martinez-San Millan J, Martinez-Vidal A. Is conservative treatment of deep neck space infections appropriate? Head Neck. 2001;23:126–133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<126::aid-hed1007>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagy M, Pizzuto M, Backstrom J, Brodsky L. Deep neck infections in children: a new approach to diagnosis and treatment. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1627–1634. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199712000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang LF, Kuo WR, Tsai SM, Huang KJ. Characterizations of life-threatening deep cervical space infections: a review of one hundred ninety-six cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:111–117. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Page C, Biet A, Zaatar R, Strunski V. Parapharyngeal abscess: diagnosis and treatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:681–686. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Marie S, Tjon ATRT, van der Mey AG. Clinical infections and nonsurgical treatment of parapharyngeal space infections complicating throat infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:975–982. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sichel JY, Attal P, Hocwald E, Eliashar R. Redefining parapharyngeal space infections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:117–123. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marques PM, Spratley JE, Leal LM. Parapharyngeal abscess in children: five year retrospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:826–830. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30544-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sichel JY, Dano I, Hocwald E. Nonsurgical management of parapharyngeal space infections: a prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:906–910. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oh JH, Kim Y, Kim CH. Parapharyngeal abscess: comprehensive management protocol. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007;69:37–42. doi: 10.1159/000096715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sichel JY, Gomori JM, Saah D, Elidan J. Parapharyngeal abscess in children: the role of CT for diagnosis and treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;35:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alaani A, Griffiths H, Minhas SS. Parapharyngeal abscess: diagnosis, complications and management in adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0800-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Parapharyngeal abscesses. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:1025–1030. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100118122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duque CS, Guerra L, Roy S. Use of intraoperative ultrasound for localizing difficult parapharyngeal space abscesses in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amar YG, Manoukian JJ. Intraoral drainage: recommended as the initial approach for the treatment of parapharyngeal abscesses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Langenbrunner DJ, Dajani S. Pharyngomaxillary space abscess with carotid artery erosion. Arch Otolaryngol. 1971;94:447–457. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1971.00770070693011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eliachar I, Peleg H, Joachims HZ. Mediastinitis and bilateral pyopneumothorax complicating a parapharyngeal abscess. Head Neck Surg. 1981;3:438–442. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890030513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Courmont P, Cade A. Sur une septico-pyohemie de l’homme simulant la peste et causee par un streptobacille anaerobie. Arch Med Exp Anat Pathol. 1900;12:393–418. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schottmuller H. Über die Pathogenität anaerober Bazillen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1918;44:1440. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;227:701–703. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sinave CP, Hardy GJ, Fardy PW. The Lemierre syndrome: suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 1989;68:85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:458–465. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ridgway JM, Parikh DA, Wright R. Lemierre syndrome: a pediatric case series and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brook I. Microbiology and management of deep facial infections and Lemierre syndrome. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65:117–120. doi: 10.1159/000070776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Le Monnier A, Jamet A, Carbonnelle E. Fusobacterium necrophorum middle ear infections in children and related complications: report of 25 cases and literature review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:613–617. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318169035e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Appelbaum PC, Spangler SK, Jacobs MR. Beta-lactamase production and susceptibilities to amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanate, cefoxitin, imipenem, and metronidazole of 320 non-Bacteroides fragilis Bacteroides isolates and 129 fusobacteria from 28 U.S. centers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1546–1550. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brazier JS, Hall V, Yusuf E, Duerden BI. Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in England and Wales 1990–2000. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:269–272. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-3-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldenberg NA, Knapp-Clevenger R, Hays T, Manco-Johnson MJ. Lemierre's and Lemierre's-like syndromes in children: survival and thromboembolic outcomes. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e543–548. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alvarez A, Schreiber JR. Lemierre's syndrome in adolescent children: anaerobic sepsis with internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis following pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 1995;96:354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hagelskjaer LH, Prag J, Malczynski J, Kristensen JH. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre's syndrome, in Denmark 1990–1995. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:561–565. doi: 10.1007/BF01708619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ramirez S, Hild TG, Rudolph CN. Increased diagnosis of Lemierre syndrome and other Fusobacterium necrophorum infections at a Children's Hospital. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e380. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Duong M, Wenger J. Lemierre syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:589–593. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000177198.91278.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aspesberro F, Siebler T, Van Nieuwenhuyse JP. Lemierre syndrome in a 5-month-old male infant: case report and review of the pediatric literature. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:e35–37. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31817319fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eykyn SJ. Necrobacillosis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1989;62:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alston JM. Necrobacillosis in Great Britain. Br Med J. 1955;2:1524–1528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4955.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moore-Gillon J, Lee TH, Eykyn SJ, Phillips I. Necrobacillosis: a forgotten disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1526–1527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6429.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanders RV, Kirkpatrick MB, Dacso CC, Bass JB., Jr Suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. Report of a case and review of the literature. Ala J Med Sci. 1986;23:92–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seidenfeld SM, Sutker WL, Luby JP. Fusobacterium necrophorum septicemia following oropharyngeal infection. JAMA. 1982;248:1348–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vincent QB, Labedan I, Madhi F. Lemierre syndrome with meningo-encephalitis, severe cerebral artery stenosis, and focal neurological symptoms. J Pediatr. 2010;157:345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.041. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rathore MH, Barton LL, Dunkle LM. The spectrum of fusobacterial infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:505–508. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hile LM, Gibbons MD, Hile DC. Lemierre syndrome complicating otitis externa: case report and literature review. J Emerg Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.02.014. Mar 25 epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:524–532. doi: 10.1086/313970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dool H, Soetekouw R, van Zanten M, Grooters E. Lemierre's syndrome: three cases and a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:651–654. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0880-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Venglarcik J. Lemierre's syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:921–923. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000091374.54304.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct – report of four cases. Radiology. 1999;213:369–374. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv09369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nguyen-Dinh KV, Marsot-Dupuch K, Portier F. Lemierre syndrome: usefulness of CT in detection of extensive occult thrombophlebitis. J Neuroradiol. 2002;29:132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brook I. Current management of upper respiratory tract and head and neck infections. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:315–323. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Charles K, Flinn WR, Neschis DG. Lemierre's syndrome: a potentially fatal complication that may require vascular surgical intervention. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:1023–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wenger JD. Epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease and impact of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines in the United States and Canada. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:S132–S136. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199809001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shah RK, Roberson DW, Jones DT. Epiglottitis in the Hemophilus influenzae type B vaccine era: changing trends. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:557–560. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200403000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Heath PT, Booy R, Azzopardi HJ. Antibody concentration and clinical protection after Hib conjugate vaccination in the United Kingdom. JAMA. 2000;284:2334–2340. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hargreaves RM, Slack MP, Howard AJ. Changing patterns of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease in England and Wales after introduction of the Hib vaccination programme. BMJ. 1996;312:160–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7024.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McEwan J, Giridharan W, Clarke RW, Shears P. Paediatric acute epiglottitis: not a disappearing entity. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:317–321. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Broadhurst LE, Erickson RL, Kelley PW. Decreases in invasive Haemophilus influenzae diseases in US Army children, 1984 through 1991. JAMA. 1993;269:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Garpenholt O, Hugosson S, Fredlund H. Epiglottitis in Sweden before and after introduction of vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:490–493. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hopkins A, Lahiri T, Salerno R, Heath B. Changing epidemiology of life-threatening upper airway infections: the reemergence of bacterial tracheitis. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1418–1421. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Faden H. The dramatic change in the epidemiology of pediatric epiglottitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:443–444. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000221347.42120.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Devlin B, Golchin K, Adair R. Paediatric airway emergencies in Northern Ireland, 1990–2003. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:659–663. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McConnell A, Tan B, Scheifele D. Invasive infections caused by haemophilus influenzae serotypes in twelve Canadian IMPACT centers, 1996–2001. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31812f4f5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Guldfred LA, Lyhne D, Becker BC. Acute epiglottitis: epidemiology, clinical presentation, management and outcome. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:818–823. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tebruegge M, Connell T, Kong K. Necrotizing epiglottitis in an infant: an unusual first presentation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:164–166. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318187a869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Faden HS. Treatment of Haemophilus influenzae type B epiglottitis. Pediatrics. 1979;63:402–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tanner K, Fitzsimmons G, Carrol ED. Haemophilus influenzae type b epiglottitis as a cause of acute upper airways obstruction in children. BMJ. 2002;325:1099–1100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7372.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wagle A, Jones RM. Acute epiglottitis despite vaccination with Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine. Paediatr Anaesth. 1999;9:549–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1999.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Marsh MJ, Murdoch IA. Acute epiglottitis after Hib vaccination. Lancet. 1994;344:829. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Heath PT, Booy R, Griffiths H. Clinical and immunological risk factors associated with Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine failure in childhood. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:973–980. doi: 10.1086/318132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mayo-Smith MF, Spinale JW, Donskey CJ. Acute epiglottitis: an 18-year experience in Rhode Island. Chest. 1995;108:1640–1647. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.6.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lacroix J, Ahronheim G, Arcand P. Group A streptococcal supraglottitis. J Pediatr. 1986;109:20–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Glenn GM, Schofield T, Krober M. Group A streptococcal supraglottitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:674–676. doi: 10.1177/000992289002901113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Berger G, Landau T, Berger S. The rising incidence of adult acute epiglottitis and epiglottic abscess. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:374–383. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.McVernon J, Slack MP, Ramsay ME. Changes in the epidemiology of epiglottitis following introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccines in England: a comparison of two data sources. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:570–572. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Shah RK, Stocks C. Epiglottitis in the United States: national trends, variances, prognosis, and management. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1256–1262. doi: 10.1002/lary.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Acevedo JL, Lander L, Choi S, Shah RK. Airway management in pediatric epiglottitis: a national perspective. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:548–551. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gonzalez Valdepena H, Wald ER, Rose E. Epiglottitis and Haemophilus influenzae immunization: the Pittsburgh experience – a five-year review. Pediatrics. 1995;96:424–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hebert PC, Ducic Y, Boisvert D, Lamothe A. Adult epiglottitis in a Canadian setting. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:64–69. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cressman WR, Myer CM., 3rd Diagnosis and management of croup and epiglottitis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1994;41:265–276. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sobol SE, Zapata S. Epiglottitis and croup. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41:551–566. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.012. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Alcaide ML, Bisno AL. Pharyngitis and epiglottitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:449–469. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.001. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.American Academy of Pediatrics . Haemophilus influenzae infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2009. pp. 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cherry JD. Clinical practice. Croup. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:384–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp072022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Peltola V, Heikkinen T, Ruuskanen O. Clinical courses of croup caused by influenza and parainfluenza viruses. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:76–78. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Buchan KA, Marten KW, Kennedy DH. Aetiology and epidemiology of viral croup in Glasgow, 1966–72. J Hyg (Lond) 1974;73:143–150. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.McConnochie KM, Hall CB, Barker WH. Lower respiratory tract illness in the first two years of life: epidemiologic patterns and costs in a suburban pediatric practice. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:34–39. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Denny FW, Murphy TF, Clyde WA., Jr Croup: an 11-year study in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1983;71:871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yun BY, Kim MR, Park JY. Viral etiology and epidemiology of acute lower respiratory tract infections in Korean children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:1054–1059. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Foy HM, Cooney MK, Maletzky AJ, Grayston JT. Incidence and etiology of pneumonia, croup and bronchiolitis in preschool children belonging to a prepaid medical care group over a four-year period. Am J Epidemiol. 1973;97:80–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sung JY, Lee HJ, Eun BW. Role of human coronavirus NL63 in hospitalized children with croup. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:822–826. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e7c18d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Choi EH, Lee HJ, Kim SJ. The association of newly identified respiratory viruses with lower respiratory tract infections in Korean children, 2000–2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:585–592. doi: 10.1086/506350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Bastien N, Chui N, Robinson JL. Detection of human bocavirus in Canadian children in a 1-year study. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:610–613. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Volz S, Schildgen O, Klinkenberg D. Prospective study of human bocavirus (HBoV) infection in a pediatric university hospital in Germany 2005/2006. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.van der Hoek L, Sure K, Ihorst G. Croup is associated with the novel coronavirus NL63. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]