Ferrets are commonly seen in many small animal veterinary practices. Special equipment needs are minimal, and the approach to handling ferrets is similar in many ways to that for dogs and cats. Ferret owners regularly seek veterinary care for a variety of reasons: ferrets need preventive vaccinations for canine distemper and rabies; ferrets have a relatively short life span compared with that of cats and dogs; ferrets in the United States and in some European countries have a high incidence of endocrine, gastrointestinal, and neoplastic diseases; and many of the diseases common to ferrets are not easily ignored by the pet owner (e.g., alopecia resulting from adrenal disease and hypoglycemic episodes caused by insulinoma).

Restraint and Physical Examination

Restraint

Most ferrets are docile and can be easily examined without assistance. However, an assistant is usually needed when taking the rectal temperature, when administering injections or oral medications, or if an animal has a tendency to bite. Young ferrets often nip, and nursing females and ferrets that are handled infrequently may bite. Unlike dogs and cats, which growl, ferrets will bite without warning. Therefore always ask the owner if the ferret will bite before handling it and take precautions accordingly. Make sure to obtain the rabies vaccination history before physical examination, as reporting and rabies protocols for animal bites from vaccinated and unvaccinated ferrets differ (see below). Ferrets that are prone to bite and are not currently vaccinated for rabies may need tranquilization for procedures that require restraint.

Depending on the ferret’s disposition, several basic manual restraint methods can be used for physical examination. For tractable animals, lightly restrain the ferret on the examination table. Examine the mucous membranes, oral cavity, head, and integument. Then pick the ferret up and use one hand for support under its body while using the second hand to auscultate the thorax and palpate the abdomen. The ferret can be scruffed at any time for vaccination, ear cleaning, or other procedures that may elicit an attempt to escape or bite. For a very active animal or one that bites, scruff the ferret at the back of its neck and suspend it with all four legs off the table (Fig. 2-1 ). Most ferrets become very relaxed with this hold, and the veterinarian is able to examine the oral cavity, head, and body; auscultate the chest; and palpate the abdomen easily. However, this method may not work for very fractious animals.

Fig. 2-1.

Restrain an active ferret by scruffing the loose skin on the back of the neck. The ferret will relax and allow you to palpate the abdomen or administer a vaccine.

To manually restrain a ferret for procedures such as venipuncture or ultrasound, hold it firmly by the scruff of its neck and around the hips without pulling the legs back. Most ferrets struggle if their legs are extended by pulling on the feet. Some animals can be distracted during a procedure by feeding a meat-based canned food (a/d Prescription Diet, Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Topeka, KS; Eukanuba Maximum-Calorie, The Iams Company, Dayton, OH) or a small amount of a supplement such as FerreTone (8-in-1 Pet Products, Islandia, NY) by syringe. Avoid products containing sugar, which can affect blood glucose values, particularly in ferrets with insulinoma.

For very fractious or anxious animals or for procedures requiring lengthy restraint, light tranquilization or sedation may be indicated (see Chapter 31).

Physical Examination

Most ferrets strenuously object to having their temperature taken with a rectal thermometer. If a ferret struggles during the examination, the temperature taken at the end of the examination may be artificially high. Therefore measure the rectal temperature early in the physical examination with a flexible digital thermometer that is well lubricated. The normal range of rectal temperature of a ferret is 100.5°F to 102.5°F (38.0°C to 39.2°C); a mean of 102°F (38.8°C), with a wider range of 100°F to 104°F (37.8°C to 40.0°C), is also reported.21 Interestingly, in normal ferrets housed outdoors at a fur farm in very cold ambient temperatures (21°F [−6.1°C]), the mean 24-hour mean core body temperature measured by sterile thermosensitive data loggers implanted in their abdomens was 99.3°F (37.4°C), with a range of 97.3°F to 101.1°F (36.3°C to 38.4°C).41

The physical examination of a ferret is basically the same as that of any small mammal and can be performed quickly and efficiently if a few simple guidelines are followed. Observe the attitude and alertness of the animal. Ferrets may sleep in the carrier in the veterinary office; however, once awakened for the examination, a ferret should be alert and responsive. Assess hydration by observing the skin turgor of the eyelids, tenting of the skin at the back of the neck, and moistness of the oral mucous membranes. However, skin turgor can be difficult to evaluate in a cachectic animal. Estimate the capillary refill time by digitally pressing on the gingiva.

Examine the eyes, nose, ears, and facial symmetry. Cataracts can develop in both juvenile and adult animals. Retinal degeneration is another ophthalmic disorder seen in ferrets and may be indicated by abnormal pupil dilation. Inspect for nasal discharge and ask the owner about any history of sneezing or coughing. The ears may have a brown waxy discharge, but the presence of excessive brown exudate may indicate infestation with ear mites (Otodectes cynotis). Bruxism often indicates gastrointestinal discomfort.

The teeth of ferrets should be clean and the gingiva pink. Dental tartar is commonly present in pet ferrets. The amount of plaque may be exacerbated by the feeding of soft foods or sugary treats, such as raisins, and is possibly related to a dry kibble diet.14 Tartar most commonly accumulates on the first and second maxillary premolars. Excessive dental tartar should be removed by dental techniques used in dogs and cats, and measures to prevent tartar buildup should be implemented. As a preventive, a pet dentifrice or tartar control toothpaste25., 32. can be applied to the teeth to decrease formation of calculus. Gingivitis, which manifests as erythematous gingival tissue that sometimes bleeds, is a common sequela of excessive dental tartar.

Ferrets often break off the tip of one or both canine teeth; however, they rarely exhibit clinical signs of sensitivity or pain associated with a fractured canine. If the tooth turns dark or the ferret exhibits sensitivity when eating, recommend a root canal or extraction, depending on the degree of damage to the tooth (see Chapter 32). Rarely, an infected root of a fractured canine can cause swelling of the ipsilateral submandibular lymph node. If swelling is present, dental radiographs, canine tooth extraction, and possibly lymph node biopsy are indicated.

Observe the symmetry of the face. Although uncommon, salivary mucoceles occur in ferrets and are noticeable as a unilateral swelling on the side of the face, usually in the cheek or temporal area (see Chapter 3).

Palpate the regional lymph nodes of the neck and axillary, popliteal, and inguinal areas. Nodes should be soft and may sometimes feel enlarged in large or overweight animals because of surrounding fat. Any degree of firmness or asymmetry in one or more nodes is suspicious and warrants a fine-needle aspirate or a biopsy. If two or more nodes are enlarged and firm, a full diagnostic workup is indicated.

Auscultate the heart and lungs in a quiet room. Ferrets have a rapid heart rate (180 to 250 beats/min) and often a pronounced sinus arrhythmia. If a ferret is excited and has a very rapid heart rate, subtle murmurs may be missed. Valvular disease, cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure are seen in ferrets, and any murmur or abnormal heart rhythm should be investigated further (see Chapter 5).

Palpate the abdomen while holding the ferret off the table, either by scruffing the neck or supporting the ferret with one hand. This allows the abdominal organs to displace downward, facilitating palpation. If the history is consistent with an intestinal foreign body or urinary blockage, palpate gently to avoid causing iatrogenic injury, such as a ruptured stomach or bladder. Palpate the cranial abdomen, paying particular attention to the presence of gas or any irregularly shaped mass in the stomach area, especially in ferrets with a history of vomiting, melena, or chronic weight loss. The spleen is commonly enlarged in ferrets; this may or may not be significant, depending on other clinical findings (see Chapter 5). Palpate a large spleen gently to avoid iatrogenic damage. A very enlarged spleen may indicate systemic disease or, very rarely, idiopathic hypersplenism, and further diagnostic workup is warranted. Always note any degree of splenic enlargement in the medical record so that this finding can be rechecked at future examinations.

Examine the genital area, observing the size of the vulva in females. Vulvar enlargement in a spayed female is consistent with either adrenal disease or an ovarian remnant; the latter is rare. If the vulva is of normal size, show this to the owner so that any vulvar enlargement in the future will be noticed. Examine the preputial area and size of the testicles of male ferrets; preputial and testicular tumors are sometimes seen.

Check the fur coat for evidence of alopecia. Alopecia of the tail tip is common in ferrets and may be incidental and transient or an early sign of adrenal disease. Symmetric, bilateral alopecia or thinning of the hair coat that begins at the tail base and progresses cranially is a common clinical finding in ferrets with adrenal disease. Examine the skin on the back and neck for evidence of scratching or alopecia. Pruritus may be present with adrenal disease (common) or with ectoparasites (fleas, Sarcoptes scabiei). Check closely visually and by searching through the hair coat with your fingers for evidence of skin masses. Mast cell tumors are common and can range in diameter from a few millimeters to over a centimeter. Often, the fur around a mast cell tumor is parted and matted with dark blood from the animal’s scratching. Other types of skin tumors, such as sebaceous adenomas and basal cell tumors, are also common (see Chapter 9). Perform an excisional biopsy of any lump found on the skin.

Preventive Medicine

Young, recently purchased ferrets need serial distemper vaccinations until they are 13 to 14 weeks of age.2 Rabies vaccines should be given annually beginning at 3 months of age.15 Ferrets should be examined annually until they are 4 or 5 years of age; middle-aged and older animals should be examined twice yearly because of the high incidence of metabolic disease and neoplasia. Annual blood tests (consisting of a complete blood count and plasma or serum biochemical analysis) are recommended for older animals. Measure the blood glucose concentration twice yearly in healthy middle-aged and older ferrets; more frequent monitoring is needed in ferrets with insulinoma. An endocrine panel is indicated in ferrets with hair loss on the tail or other clinical signs suggestive of early adrenal disease (see Chapter 7). Testing for infectious diseases may be warranted, especially in new ferrets that will be introduced into a multi-ferret household or those that are taken to ferret shows. Currently, ferrets can be tested for Aleutian disease virus and ferret enteric coronavirus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing (Michigan State University, Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health, www.animalhealth.msu.edu; Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics, www.vmdlabs.com). Serologic tests for Aleutian disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and counterimmunoelectrophoresis (CIEP) are also available (see Chapter 5).

Vaccinations

Canine Distemper

Ferrets must be vaccinated against canine distemper virus. Currently, one vaccine is approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for use in ferrets: PureVax (Merial, Athens, GA). Because PureVax is a canarypox-vectored recombinant vaccine it does not contain adjuvants or the complete distemper virus; thus many of the postvaccination risks have been reduced. This product has a wide safety margin and has proved effective in protecting ferrets against canine distemper infection.58 Another distemper vaccine that was widely used previously (Fervac-D, United Vaccines, Inc., Madison, WI) is no longer available. Fervac-D was a modified live virus vaccine propagated in avian cell lines. Another modified live canine distemper vaccine (Galaxy D, Merck/Schering-Plough Animal Health, Whitehouse Station, NJ) has been studied for safety and efficacy in ferrets. This product, derived from the Onderstepoort distemper strain and attenuated in a primate cell line, proved effective in preventing canine distemper in young ferrets challenged after serial vaccination.64 However, duration of immunity with this product is not known, and its use in clinical animals is extralabel, requiring informed owner consent. Although no vaccine reactions were reported in the study, the incidence of vaccine reactions with Galaxy D is unknown because experience with repeated long-term use in ferrets has been limited.64 Because of the possibility of vaccine-induced disease, especially in immunosuppressed or sick ferrets, do not use combination canine vaccines or vaccines of ferret cell or low-passage canine cell origin.

In young ferrets, the half-life of maternal antibody to canine distemper virus is 9.43 days.2 Vaccinate young ferrets for distemper at 8 weeks of age, then give two additional boosters at 3-week intervals for a total of three vaccinations. Give booster vaccines annually.

Rabies

All ferrets should be vaccinated against rabies.15 A killed rabies vaccine is approved for use in ferrets (Imrab-3 or Imrab-3 TF, Merial, Duluth, GA) and is effective in producing immunity for at least 1 year.55 Current recommendations are to vaccinate healthy ferrets at 3 months of age at a dose of 1 mL administered subcutaneously. Give booster vaccinations annually. Titers develop within 30 days of rabies vaccination.55

In ferrets that were experimentally inoculated intramuscularly with skunk-origin rabies virus, the mean incubation period was 33 days and the mean morbidity period was 4 to 5 days.42 Clinical signs were ascending paralysis, ataxia, cachexia, bladder atony, fever, hyperactivity, tremors, and paresthesia. Virus antigen was present in the brain tissue of all ferrets with clinical signs of rabies, and virus was isolated from the salivary gland of one ferret. In a similar study of ferrets inoculated with a raccoon rabies isolate, the mean incubation period was 28 days. Virus was isolated from the salivary glands of 63% of rabid ferrets, and 47% shed virus in saliva. Virus excretion began from 2 days before until 6 days after the onset of illness.43 In an earlier study of ferrets with experimentally induced rabies, only mild clinical signs were observed before death.7 Infected ferrets exhibited restlessness and apathy, and some showed paresis. Sick animals did not attempt to bite when threatened, and virus was not excreted in the submaxillary salivary glands of animals that died. In this study, the authors concluded that ferrets are 50,000 times less susceptible to rabies than fox and 300 times less susceptible than hares. In another study, ferrets that were fed up to 25 carcasses of mice infected with rabies did not develop the disease; in contrast, skunks become fatally infected after the consumption of only one carcass.4

Ferrets are considered currently immunized 28 days after the initial rabies vaccination and immediately after a booster vaccination.15 If a healthy pet ferret bites a person, current recommendations of the Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control are to confine and observe the animal for 10 days; the ferret should not be vaccinated during this period.15 If signs of illness develop, this should be reported to the local health department and a veterinarian should evaluate the animal. If signs suggest rabies, the ferret must be euthanized and protocols for rabies evaluation should be followed. If a stray ferret bites a person, the ferret must be euthanized and submitted immediately for rabies testing. For a vaccinated ferret exposed to a possible rabid animal, recommendations are to revaccinate the ferret immediately and quarantine for 45 days. An unvaccinated animal that is exposed to a rabid animal should be euthanized immediately and submitted for rabies testing. See the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5702a1.htm) or the National Association of Public Health Veterinarians (www.nasphv.org/) for specific guidelines.

Vaccine-Associated Adverse Events

In ferrets, adverse events associated with vaccination are primarily type I hypersensitivity reactions or anaphylaxis.37 Type I hypersensitivity reactions involve lymphoid tissue associated with mucosal surfaces (skin, intestines, and lungs) and result from the interaction of antigen and immunoglobulin E in mast cells or basophils. Ferrets with mild reactions may exhibit pruritus and skin erythema. More severe reactions are typified by vomiting, diarrhea, piloerection, hyperthermia, cardiovascular collapse, or death.

Vaccine reactions are most common after distemper vaccination but may also occur after rabies vaccination. In a study of vaccine reactions in 3,857 ferrets, the incidence of adverse events associated with rabies vaccine alone, distemper vaccine alone, and rabies and distemper vaccines together were 0.51%, 1.0%, and 0.85%, respectively. The incidence of adverse events did not differ significantly among these three groups; however, the cumulative number of distemper vaccinations received was significantly associated with the occurrence of an adverse event. The distemper vaccines used in this population of ferrets were PureVax and Fervac D; however, the two distemper vaccines were grouped collectively in the analysis, and the incidence of adverse events associated with the individual distemper vaccines was not reported. Sex, age, and body weight were not associated with occurrence of an adverse event. All reactions occurred immediately after vaccination and most commonly consisted of vomiting and diarrhea. In another study of 143 ferrets, the incidence of adverse events after administering distemper (5.9%) (Fervac D), rabies (5.6%) (Imrab-3), or both vaccines (5.6%) was not significantly different. In a 2001 report of vaccine reactions in ferrets reported to the United States Pharmacopeia Veterinary Practitioners’ Reporting Program, 65% (54 of 83) of reports involved administration of FerVac D; 24% (20 of 83) involved concomitant administration of FerVac D and Imrab; and 11% (9 of 83) involved administration of Imrab alone (PureVax was not approved for use at the time these data were collected).37 According to Merial’s product information, the incidence of vaccine reactions with PureVax is 0.3%. No data are available for products not licensed for use in ferrets. Veterinarians are not required to report vaccine-associated adverse events, and surveillance of these events is passive, relying on voluntary reporting by practitioners.37 Vaccine-associated adverse events can be reported to the Center for Biologics, U.S. Department of Agriculture (1-800-752-6255; www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/vet_biologics/vb_adverse_event.shtml).

Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for vaccine administration and inform the owner of the possibility of a reaction before vaccinating. Have the owner monitor the ferret in the waiting area for 30 minutes or more after vaccination with any product. As stated, most reactions occur almost immediately after vaccination.

If a ferret has an adverse reaction, administer an antihistamine (e.g., diphenhydramine hydrochloride [Benadryl, Parke-Davis, Morris Plains, NJ], 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg intravenously [IV] or intramuscularly [IM]), epinephrine (20 μg/kg IV, IM, subcutaneously [SC], or intratracheally), or a short-acting corticosteroid (e.g., dexamethasone sodium phosphate, 1 to 2 mg/kg IV or IM), and give supportive care.

For any biologic product, veterinarians must assess risk versus benefit of vaccination. The treatment options for ferrets that have had a vaccine reaction include not vaccinating if the risk of exposure is minimal; administering diphenhydramine (2 mg/kg orally [PO] or SC) at least 15 minutes before vaccination; or, for distemper, administering a different product.

Vaccine injection-site sarcomas have been described in ferrets.39., 40. In one report, 7 of 10 fibrosarcomas in ferrets were from locations used for vaccination.39 Fibrosarcomas from injection sites had a high degree of cellular pleomorphism and similar histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features as those reported for feline vaccine-associated sarcomas. In the reported cases in ferrets, no definitive association could be made between the fibrosarcoma and the type of vaccine. In cats, adjuvanted vaccines are most likely to be involved in tumor development. However, although injection-site sarcomas may occur in ferrets, ferrets appear less prone than cats to tumor development. In a study of vaccine reactions in ferrets, mink, and cats, cats had more lymphocytes at the injection site than either ferrets or mink after vaccination with three different rabies vaccines.11 Results of this study suggest a lower species susceptibility to vaccine-associated sarcomas in ferrets than in cats.

Parasites

Endoparasites

Gastrointestinal parasitism is uncommon in domestic ferrets. Rarely, pet ferrets may become infected with parasites from other natural hosts through intermediate hosts or vectors. Protozoan parasites are occasionally seen. Therefore perform routine fecal flotations and direct fecal smears for all young ferrets at the initial examination.

Coccidiosis (Isospora species) is seen infrequently, usually in young ferrets, which shed oocysts between 6 and 16 weeks of age.3 The infection is usually subclinical; occasionally, however, ferrets may have loose stool or bloody diarrhea. Treatment of ferrets with coccidiosis is similar to that of other small animals and should be continued for at least 2 weeks. Coccidiostats, such as sulfadimethoxine and amprolium, are effective and safe. The Isospora species that infect ferrets may cross-infect dogs and cats; therefore other pets in the household should be checked for coccidia and treated as needed.

Giardiasis is occasionally seen in ferrets. Results of a recent study on molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis isolates from pet ferrets show that genetic sequences from isolates in ferrets differ from isolates of humans and other animals, suggesting that Giardia isolates from ferrets may be host specific.1 Giardia species can be detected by identifying cysts or trophozoites in a fresh fecal smear or zinc sulfate flotation, or by fecal ELISA. Treat ferrets with giardiasis with metronidazole (20 mg/kg PO q12h) for 5 to 10 days. Fenbendazole (50 mg/kg PO q24h for 3 to 5 days) is used in dogs and cats, but safety and efficacy in ferrets are unknown.

Cryptosporidiosis can occur in a high percentage of young ferrets.53 Infection is usually subclinical in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed animals. Although most immunocompetent animals recover from infection within 2 to 3 weeks, infection can persist for months in immunosuppressed animals. Oocysts of Cryptosporidium are small (3 to 5 μm) and difficult to detect but can be found in samples of fresh feces examined immediately after acid-fast staining.3., 53. No treatments exist for Cryptosporidium infection. Because of the zoonotic potential, ferrets may be a source of infection for human beings, especially immunocompromised individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).53

Heartworms (Dirofilaria immitis) can cause disease in ferrets. Ferrets that are housed outdoors in heartworm-endemic areas are most susceptible to infection; however, all ferrets in endemic areas should be given preventive medicine. Oral administration of ivermectin is currently the most practical preventive measure because it is administered once per month (see Chapter 5 and AppendixChapter 5Appendix).

Ectoparasites

Ear mites (Otodectes cynotis) are common in ferrets, but affected animals rarely exhibit pruritus or irritation. This mite species also infects dogs and cats, and animals in households with multiple pets can transmit mites to other animals. A red-brown, thick, waxy discharge in the ear canal and pinna characterizes infection. A direct smear of the exudate reveals adult mites or eggs. Because ferrets normally have brown ear wax, the color or appearance of debris in the ear canal is not pathognomonic for mites. At the initial examination, check all ferrets for ear mites and do follow-up checks at the annual examination in ferrets kept in multiple-pet households. Several products, including selamectin, are effective in treatment (see Chapter 9).

Flea infestation (Ctenocephalides species) is most common in ferrets kept in households with dogs or cats. Ferrets with chronic infestation can become severely anemic. Check all ferrets during the physical examination for signs of fleas or flea dirt. Treat infested animals with products safe for use in cats and institute flea control measures (see Chapter 9).

Ticks are rarely seen in domestic ferrets, and Lyme disease in ferrets has not been reported.

Hospitalization

Ferrets can be hospitalized in standard stainless steel hospital cages with some adaptations. Ferrets are agile escape artists and can squeeze through even very small openings. In many standard cages designed for veterinary hospitals, the bar spacing is too wide, allowing an easy avenue of escape. For housing ferrets, use only cages with small spacing between vertical bars or use cages with small crossbars. Alternatively, adapt standard cages for use by attaching a Plexiglas plate to the front of the cage at least half the height of the cage door or higher. The plate will prevent escape through the bars yet can be easily detached and cleaned.

Commercial hospital cages with Plexiglas fronts and access ports can be used for ferrets. There is no avenue of escape, and ferrets are visible at all times. Acrylic or laminate animal intensive care cages or incubators also can be used to house ferrets and are especially useful for animals that need supplemental heat or oxygen. The cage should be large enough to accommodate a sleeping area or box and an area for defecation and urination. Ferrets are very careful about not soiling their sleeping area, even when very sick.

All ferrets like to burrow and should be given opportunity to do so while hospitalized. Clean towels make excellent burrowing material. Alternatively, a mound of shredded paper provides much satisfaction to hospitalized animals. If not provided with burrowing material, many ferrets will burrow underneath the cage paper. Extra-small padded pet beds and fleece pet “pockets” work well as sleeping areas.

An oxygen cage should be available for use with dyspneic animals. Monitor the temperature in commercial oxygen cages closely, because ferrets can become hypothermic quickly at cool cage temperatures that are used for dogs and cats. Conversely, ferrets can overheat at temperatures used for avian patients.

Provide water for hospitalized ferrets in either water bottles or small weighted bowls. Ask the owner which type of watering system the ferret is accustomed to before hospitalization. Ferrets can be finicky eaters and should be fed their regular diet while hospitalized, if possible. Otherwise, feed a very palatable ferret food or a premium-quality, high-protein cat or kitten chow. If dietary changes are needed in the regular diet, recommend that changes be made gradually after the ferret has been released from the hospital. For animals that are anorexic, force-feed a high-calorie semisolid food or supplement until the animal is eating on its own (see later discussion).

Clinical and Treatment Techniques

Venipuncture

Obtaining a blood sample from a ferret is relatively easy and usually does not require anesthesia. Several venipuncture sites are readily accessible; the technique and site chosen depend on how much blood is needed and the availability of assistants for restraint. Anesthesia or tranquilization can be used if assistants are unavailable, but anesthesia may affect hematologic values (see later discussion).35 Ferrets often can be distracted during restraint for venipuncture by offering semi-solid food or a product such as FerreTone (8-in-1 Pet Products) by syringe. Avoid using supplements with corn syrup or other sugars, as this will affect blood glucose levels, and collect blood for glucose determination or other fasting samples before offering food.

Most veterinary laboratories offer small mammal hematologic and biochemical panels that can be done with 1.0 mL or less of blood. In-clinic point-of-care analyzers require very small sample sizes (usually 100 μL). The blood volume of healthy ferrets is approximately 40 mL in average-sized females weighing 750 g and 60 mL in males weighing 1 kg.21 Up to 10% of the blood volume can be safely withdrawn at one time in a normal ferret, but collect only the minimum amount needed for analysis. Repeated blood drawing can contribute to anemia in sick animals hospitalized for long periods.

Two sites are commonly accessed to obtain large blood volumes in ferrets. The jugular vein can be approached in the neck by using the conventional technique used in cats, with the forelegs extended over the edge of a table and the neck extended up (Fig. 2-2 ). Use a 25-gauge needle with a 1- to 3-mL syringe for venipuncture in most ferrets; a 22-gauge needle can be used in large males. Shave the neck at the venipuncture site to enhance visibility of the jugular vein. The vein is relatively superficial and is located more lateral in the neck than it is in dogs or cats, and it is sometimes difficult to locate in heavy males. Once the needle is inserted, the blood should flow easily into the syringe; if the neck is overextended and the head is arched back, the blood may not flow readily from the vein. Relax the hold on the head or gently “pump” the vein by moving the head slowly up and down to enhance blood flow into the syringe. With ferrets that resist limb extension, a towel-wrap technique can be used.9 Scruff the ferret with its front legs extended caudally against the ventral thorax, and wrap the animal’s body firmly with a towel from the base of the neck down. An assistant is needed to restrain the toweled ferret in dorsal recumbency while scruffing the cranial neck. Apply pressure lateral to the thoracic inlet to visualize or palpate the jugular vein lying between the thoracic inlet and the base of the ear. However, with very fractious animals, even this technique may be difficult without tranquilization.

Fig. 2-2.

Restraint for jugular venipuncture in a ferret. Restrain the ferret similar to a cat, with the legs pulled down and the head back. Shave the neck to improve visibility of the jugular vein in the lateral neck. After the vein is punctured, the head can be “pumped” up and down slowly to facilitate blood flow.

The second venipuncture site to obtain large blood samples is the cranial vena cava. The actual site of venipuncture has been called the thoracic portion of the jugular vein12., 60.; however, anatomically it is more likely the right or left brachiocephalic trunk or the anterior vena cava itself, depending on the point of entry and the depth of needle penetration (Fig. 2-3 , A). This technique is safe in ferrets because of the long anterior vena cava and the caudal location of the heart in the thoracic cavity, which is approximately 3 cm from the thoracic inlet. However, rare instances of hemorrhage into the anterior thoracic cavity can occur. Restrain the ferret on its back with the forelegs pulled caudally and the head and neck extended (Fig. 2-3, B). In an unanesthetized ferret, two assistants are usually needed, one for restraint of the forelegs and head and the other for restraint of the rear just cranial to the pelvis. Insert a 25-gauge needle with an attached 1-mL or 3-mL syringe into the thoracic cavity between the first rib and the manubrium at an angle 30 to 45 degrees to the body. Direct the needle toward the opposite rear leg or most caudal rib and insert it almost to the hub. Pull back on the plunger as the needle is slowly withdrawn until blood begins to fill the syringe. If the ferret struggles, quickly withdraw the needle and wait until the ferret is quiet before making a second attempt. In very fractious or active ferrets, jugular venipuncture or use of tranquilization are safer choices to avoid lacerating the vessels.

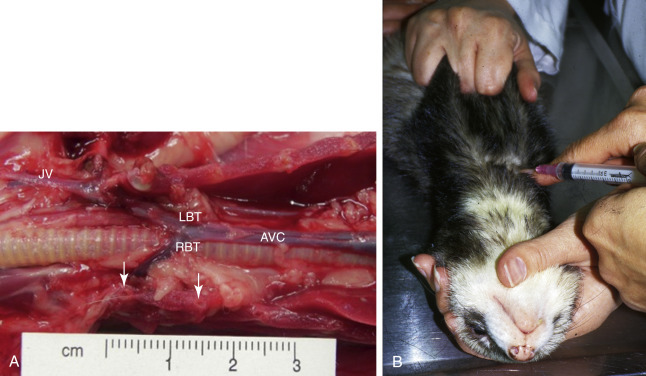

Fig. 2-3.

A, Dissection of the thoracic cavity of a ferret illustrating the site for blood collection using the anterior vena cava technique. The sternum and ventral ribs are removed. The site of venipuncture is either the right brachiocephalic trunk (RBT) or left brachiocephalic trunk (LBT) or the anterior vena cava (AVC), depending on the point of entry and depth of penetration (see marker). The jugular vein (JV) is usually lateral and cranial to the venipuncture site. The base of the first two ribs are shown by arrows.B, A ferret is restrained for venipuncture of the anterior vena cava. Both forelegs are pulled back, hindlegs are restrained, and the neck is extended.

The lateral saphenous or cephalic vein can be used if only a small amount of blood is needed to measure a packed cell volume or blood glucose level. To prevent collapse of the vein during venipuncture, use an insulin syringe with an attached 27- or 28-gauge needle. The saphenous vein lies just proximal to the hock joint on the lateral surface of the leg; the cephalic vein is in the same anatomic location as in a dog. Before venipuncture, shave the fur from the area to enhance visibility of the vein.

Although rarely used in pet ferrets, venipuncture of the tail artery is described to obtain blood samples.8 Venipuncture at this site can be painful; anesthetize the ferret for this technique. The artery is located 2 to 3 mm deep to the skin. Insert a syringe with a 21-gauge needle into the ventral midline of the tail directed toward the body. Once the artery is entered, slowly withdraw the plunger until blood fills the syringe. Apply pressure to the venipuncture site for 2 to 3 minutes after the needle has been withdrawn.

Reference Ranges

Published reference intervals for hematologic, biochemical, and plasma electrophoresis values in ferrets are listed in Table 2-1, Table 2-2, Table 2-3 . Other published sources of reference intervals for ferrets are available.21., 22. Additionally, most clinical veterinary laboratories routinely provide reference intervals for ferret hematologic and biochemical values.

Table 2-1.

Reference Intervals for Hematologic Values in Ferrets

| Value | Combined Sexa | ALBINO37 |

FITCH16 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maleb | Female | Malec | Female | ||

| Hematocrit (%) | 36-48 | 44-61 | 42-55 | 46-57 | 47-51 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2-16.5 | 16.3-18.2 | 14.8-17.4 | 15.2-17.7 | 15.2-17.4 |

| Red blood cells (×106/μL) | 7.01-9.65 | 7.30-12.18 | 6.77-9.76 | - | - |

| Reticulocytes (%) | - | 1-12 | 2-14 | - | - |

| White blood cells (×103/μL) | 4.3-10.7 | 4.4-19.1 | 4.0-18.2 | 5.6-10.8 | 2.5-8.6 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 18-47 | 11-82 | 43-84 | - | - |

| (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 616-7020 | 725-2409 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 41-73 | 12-54 | 12-50 | - | - |

| (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 1728-4704 | 1475-5590 |

| Monocytes (%) | 0-4 | 0-9 | 2-8 | - | - |

| (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 0-432 | 100-372 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0-4 | 0-7 | 0-5 | - | - |

| (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 112-768 | 50-516 |

| Basophils (%) | 0-2 | 0-2 | 0-1 | - | - |

| (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 0-112 | 0-172 |

| Bands (cells/μL) | - | - | - | 0-972 | 0-248 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 200-459 | 297-730 | 310-910 | - | - |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 50-54 | - | - | - | - |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15-18 | - | - | - | - |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (g/dL) | 32-35 | - | - | - | - |

Combined male and female pet ferrets (n = 60). From Cray C, Avian and Wildlife Laboratory, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL.

Intact males.

Castrated males.

Table 2-2.

Reference Intervals for Biochemical Values in Ferrets

| Analyte | Plasmaa | SERUM |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Albinob | Fitchc | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 65-128 | - | 82-289 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.5-4.0 | 2.6-3.8 | 3.3-4.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 25-60 | 9-84 | 25-60 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 26-36 | - | - |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 70-100 | 28-120 | |

| Bilirubin, total (mg/dL) | 0.2-0.5 | <1.0 | - |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 18-32 | 10-45 | 12-43 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.1-9.5 | 9.0-11.8 | 8.6-10.5 |

| Carbon dioxide (mmol/L) | 22-29 | 16-25 | - |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 119-163 | 64-296 | - |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | - | 106-125 | 102-121 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.2-0.5 | 0.4-0.9 | 0.2-0.6 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (U/L) | 55-93 | - | - |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 80-117 | 94-207 | 62-134 |

| Gamma glutamine transferase (U/L) | 8-34 | - | - |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 200-1400 | - | - |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.1-6.5 | 4.0-9.1 | 5.6-8.7 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.5-6.1 | 4.5-7.7 | 4.3-5.3 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142-148 | 137-162 | 146-160 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 4.5-6.2 | 5.1-7.4 | 5.3-7.2 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 30-140 | - | - |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 1.3-1.9 | - | - |

Combined male and female pet ferrets (n = 60). From Cray C, Avian and Wildlife Laboratory, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL.

Combined values of male (n = 40) and female (n = 24) ferrets.37

Combined values of intact male, female, and castrated male ferrets (n = 13), age 4-8 months.16

Table 2-3.

Reference Intervals for Plasma Protein Electrophoresis in Ferrets

| Analyte | Combined Sexa |

|---|---|

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.50-3.31 |

| Alpha-1 globulin (g/dL) | 0.33-0.56 |

| Alpha-2 globulin (g/dL) | 0.36-0.60 |

| Beta globulin (g/dL) | 0.83-1.20 |

| Gamma globulin (g/dL) | 0.31-0.81 |

| Albumin/globulin ratio | 1.05-1.33 |

Combined male and female ferrets, n = 60. From Cray C, Avian and Wildlife Laboratory, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL.

Published reference intervals for white blood cell (WBC) counts in ferrets vary from 2.5 to 19.1 × 103 cells/μL21., 27., 61.; however, WBC counts generally tend to be low in ferrets. In one study, mean WBC values were 5.7 and 5.6 × 103 cells/μL in male and female ferrets, respectively.22 High WBC counts are not seen as commonly in ferrets as in dogs and cats, perhaps in part because infectious bacterial diseases are comparatively uncommon in ferrets.

Isoflurane anesthesia can cause decreases in all hematologic values beginning at induction of anesthesia and reaching maximal effects at 15 minutes after induction.35 Therefore the complete blood count values of blood samples collected while a ferret is anesthetized must be carefully interpreted.

Reference intervals for blood coagulation times in ferrets have been published. In a recent study, blood samples were collected into sodium citrate in a ratio of 9:1 from 18 clinically healthy ferrets (12 males, 6 females, all neutered).6 Results showed some variation in values obtained by the method used for measurement. Mean prothombin time (PT) was 12.3 seconds (range, 11.6 to 12.7 seconds) measured by fibrometer and 10.9 seconds (range, 10.6 to 11.6 seconds) measured by an automated coagulation analyzer. Mean activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was 18.7 seconds (range, 17.5 to 21.1 seconds) by fibrometer and 18.1 seconds (range, 16.5 to 20.5 seconds) by automated coagulation analyzer. Mean fibrinogen concentration was 107.4 mg/dL (range, 90.0 to 163.5 mg/dL), and mean antithrombin activity (AT) was 96% (range, 69.3% to 115.3%).6 In another study, the mean PT was 15.7 seconds (range, 14.4 to 16.5 seconds) in male ferrets.61 In a study of 6 ferrets, values of clotting time of whole blood were 2.0 ± 0.5 minutes in glass tubes and 3.0 ± 0.9 minutes in siliconized tubes; mean PT was 10.3 ± 0.1 seconds; aPPT was 18.4 ± 1.4 seconds; and thrombin time was 28.8 ± 8.7 seconds.31 In the same study, mean values for individual coagulation factors were also determined31 and have been reported elsewhere.17 In a study of 30 intact ferrets (15 male, 15 female), mean bleeding time was less than 2 minutes; PT was 8 to 11 seconds for females and 9 to 10.6 seconds for males; and aPPT was 16 to 21 seconds for females and 17 to 25 seconds for males (E. Ivey, DVM, unpublished data, 2000). In this study, PT and aPPT were measured with the ACT II (Medtronic, Parker, CO).

Intravenous Catheters

Indwelling intravenous catheters are routinely used in ferrets. Catheters can be placed in the lateral saphenous or cephalic vein (Fig. 2-4 ). Jugular vein catheters are difficult to place and are rarely used. Except in very depressed animals, catheters are placed with the ferret tranquilized or anesthetized. Applying a topical anesthetic containing lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5% (EMLA cream, AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, DE) on the venipuncture site approximately 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure may facilitate catheterization in the unanesthetized ferret. Shave and sterilely prepare the skin over the vein. Puncture the skin over the vein with a 20- or 22-gauge needle, taking care to avoid the vein; then introduce a short 22-, 24-, or 26-gauge over-the-needle catheter into the vein. Secure the catheter hub or a tape butterfly wrapped around the hub directly to the skin with suture, tape, or tissue adhesive. Attach a T-connector and wrap the leg with a soft padded bandage. Closely monitor ferrets with indwelling catheters to prevent the fluid line from entangling, and frequently check the leg distal and proximal to the catheter for soft tissue swelling. Most ferrets do not chew a catheter once it is placed and do not require an Elizabethan collar.

Fig. 2-4.

Placing an indwelling catheter in the cephalic vein of a ferret. The hair over the vein is shaved and the vein held off. A 24-gauge, three-quarter–inch intravenous catheter is introduced into the cephalic vein and taped in place.

In ferrets that are collapsed with poor blood pressure or in young or very small ferrets, attempts to place an intravenous catheter may be unsuccessful. An intraosseous catheter can be placed in these animals. Contraindications to intraosseous catheterization include local infection or burns, fracture of the ipsilateral extremity, osteopenia, or osteopetrosis.59 The proximal tibia is the most common site for intraosseous catheter placement in small mammals,28 but the proximal femur can also be used; the latter site allows the patient more range of movement. Unless the ferret is very depressed, anesthesia is required to place the catheter. Sterilely prepare the insertion site, and in the conscious patient, infiltrate the area with 1% to 2% lidocaine (maximum dose 1 mg/kg).28 Insert a 20- or 22-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle into the marrow cavity. Alternatively, use a 20- or 22-gauge hypodermic needle with a surgical steel wire inserted into the lumen to prevent the needle from occluding during insertion.46 The intraosseous catheter should occupy approximately 33% to 67% of the marrow cavity at the narrowest portion.28 In humans, medications and blood products intended for intravenous administration are considered safe to administer via an intraosseous catheter.59 Therapeutic agents should be administered in small volumes while applying minimal pressure to prevent leakage from the insertion site.59 If possible, change to an intravenous catheter as soon as the animal is rehydrated or blood pressure improves. Intraosseous catheters should not be left in place for more than 72 hours.28

Vascular access ports, consisting of an indwelling intravenous catheter attached to an injection port placed in subcutaneous tissue, have been used in ferrets for repeated administration of chemotherapeutic medications. These ports can be used when repeated vascular access is required for any reason.52 The technique used to place the catheter and port has been described and illustrated.47

Fluid Therapy

Hospitalized ferrets usually require fluid therapy to maintain hydration and correct dehydration. Daily fluid requirements of ferrets have not been determined; however, calculating fluid requirements based on rates used in cats (60 to 70 mL/kg per day) appears to be adequate for maintenance. One source estimates daily water consumption of adult ferrets as 75 to 100 mL/day.38 Provide additional fluids to compensate for ongoing fluid loss and to correct dehydration calculated as a percentage of the body weight.

Give fluids subcutaneously or intravenously; intravenous fluids are preferred in ill animals. Administer subcutaneous fluids in the loose skin along the back and dorsal cervical area, dividing the calculated daily fluid volume into doses given two or three times daily. Ferrets often react painfully to subcutaneous fluid administration, and good restraint is needed to prevent a ferret from biting its handler.

If possible, administer intravenous fluids by continuous rate infusion. Alternatively, administer fluids by dividing the calculated daily fluid volume into two or three doses administered by a Buretrol (Baxter Healthcare, Glendale, CA) or syringe pump. Depending on the clinical condition of the ferret, supplements and drugs can be added to fluids by using the same criteria and calculations as for dogs and cats.

Colloids are effective in improving intravascular fluid volume and oncotic pressure in ferrets that are hypoproteinemic or in shock. Dosage and administration are similar to those in small animals (see Chapter 38). Most commonly, hydroxyethyl starch (hetastarch) is given at a dosage of 10 to 20 mL/kg per day. When hetastarch is coadministered with crystalloids, reduce the crystalloid fluid volume by 33% to 50%. In ferrets in shock, hetastarch can be given as a bolus at 5 mL/kg over a 15- to 30-minute period; this can be repeated to a total dose not exceeding 20 mL/kg per day.

Antibiotic and Drug Therapy

Ferrets are given antibiotics and other drugs at dosages similar to those used in cats (see Appendix). Intravenous antibiotics are preferred in sick animals if an indwelling catheter is in place, but the catheterized extremity should be monitored carefully for phlebitis and cellulitis, particularly when caustic medications are administered. Intramuscular antibiotics can be given, but subcutaneous administration is preferred because of the limited muscle mass in cachectic animals if therapy continues over several days. Because pills are very difficult to administer, oral medications are most easily given in a liquid form. Most compounding pharmacists can prepare suspensions of drugs that are not commercially available as liquids. Ferrets generally accept chicken and beef flavors; avoid fish flavors in compounded formulas, as ferrets do not generally like this taste.

Pain Management

Pain management is important in the postoperative period, with diseases that create significant discomfort (such as gastrointestinal ulceration), and for traumatic injuries (see Chapter 31). Ferrets in pain may exhibit tachypnea, a stiff gait, a strained facial expression, teeth grinding, shivering, half-closed eyelids, aggression, focal muscle fasciculations, hiding, general malaise, bristling of tail fur, and being “tucked” in the abdomen.36., 62. Many analgesic agents are used effectively in ferrets, including opioids, alpha-2 agonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics.26 Clinically, buprenorphine, butorphanol, and meloxicam are most commonly used for hospitalized animals and outpatients (see Chapter 31 and AppendixChapter 31Appendix). For severe pain, combination therapy, such as with an opioid and an NSAID, may be most effective.26

Epidural administration of analgesics preoperatively appears to be effective in helping to control postoperative pain in ferrets (see Chapter 31). Epidural anesthesia and analgesia is most effective in procedures involving the abdomen, spine, pelvis, hind legs, tail, and perineum.18 In a study of ferrets undergoing ovariohysterectomy and bilateral anal sacculectomy, both physiologic and behavioral manifestations of pain were attenuated in ferrets that received epidural morphine preoperatively compared with control ferrets, and beneficial effects were seen for at least 24 hours.57 The technique has been well described and illustrated.18., 23. Place the anesthetized ferret in sternal recumbency with the legs flexed to open the lumbosacral space. Clip a large rectangle of hair over the injection site (so that anatomic landmarks can easily be identified) and aseptically prepare the area. The injection site is at the intersection of a line drawn between the cranial aspect of the wings of the ilea and a line drawn between the dorsal spinous processes of the last lumber and first sacral (S1) vertebrae; the dorsal spinous process of S1 is easily palpable. Either a 22-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle or a 25-gauge hypodermic needle can be used, although a spinal needle will prevent creation of a skin plug that can obstruct the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or set up a nidus for infection and inflammation.18 Insert the needle on the midline perpendicular to the skin and with the bevel facing cranially. A correctly placed needle will drop through the lumbosacral space until it encounters bone on the ventral floor of the spinal canal. If using a spinal needle, remove the stylet and observe the needle hub for blood or CSF. Confirm correct epidural placement by attaching a 1-mL syringe containing 0.2 mL of sterile saline and 0.2 mL of air and applying gentle suction; no CSF or blood should be seen in the needle hub. No resistance should be encountered when the fluid is injected, and the air space above the fluid should not be compressed. Once correct epidural placement is confirmed, inject analgesic or anesthetic fluids slowly to avoid an increase in intracranial pressures or extended cranial infiltration of the anesthetic block. Morphine is often used for epidural analgesia at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg.23 Epidural injection is contraindicated in cases of coagulopathy, sepsis, hypovolemia, skin infection, and local fractures.18

Be careful in the immediate postoperative period when using drugs such as butorphanol, which can cause a pronounced sedative effect. Ferrets can remain very lethargic and immobile for long periods and can overheat quickly if a heating lamp or other strong heat source is used. Therefore closely monitor the body temperature of any immobile or lethargic ferret given pain medication to prevent overheating when using heat lamps or forced air warming devices. The frequent temperature spike described in ferrets 30 minutes or longer after surgery or sedation may be related to administration of various analgesics, similar to a syndrome seen in cats; however, responses in ferrets are inconsistent.29

Like cats, ferrets are sensitive to acetaminophen toxicity.16 The activity of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase in their livers is similar to that of cats. Therefore acetaminophen glucuronidation is slower in ferrets than in other non-felid species. Unlike cats, however, no genetic mutations are associated with this slow metabolism, and the exact cause is not known. When dosed inappropriately, ibuprofen can also be toxic in ferrets.13 Therefore use any NSAIDs with caution. Do not use NSAIDs in ferrets already being treated with a corticosteroid for insulinoma or other disease.

Nutritional Support

Many sick ferrets are either cachectic or have minimal body fat and require nutritional support. Force-feeding is also important to prevent hypoglycemia in anoretic ferrets with insulinomas. Ferrets can be syringe fed meat-based soft foods marketed for hospitalized dogs and cats such as Maximum-Calorie (The Iams Company) or Canine a/d (Hill’s Pet Nutrition). Alternatively, products formulated as recovery diets for carnivores are available and readily accepted by most ferrets (Carnivore Care, Oxbow Animal Health, Murdock, NE; Emeraid Carnivore, LafeberVet.com, Cornell, IL). Although readily accepted, commercial supplement gels based on corn syrup should be offered cautiously or not at all because of the high sugar content.

Force-feed anorectic ferrets as much as they will accept comfortably, usually 8 to 12 mL fed three or four times daily. Use a syringe to administer food. Once a ferret develops a taste for the food, it may eat it directly from a bowl.

Although rarely used clinically, esophagostomy feeding tubes can be placed in ferrets to manage debilitated animals over the long term. The technique is similar to that used in cats.20 Gastric feeding tubes have been placed in ferrets both experimentally and clinically.5., 10. In a study of 14 ferrets, gastrostomy tubes were placed percutaneously by a nonendoscopic technique. A gastrostomy tube was placed in a ferret after surgical repair of an esophageal perforation caused by an esophageal foreign body.10 The tube was maintained successfully throughout the postoperative healing period.

Total nutrient admixtures have been formulated to provide partial parenteral nutrition to ferrets.46., 54. Parenteral nutrition should be considered if an esophageal, gastric, or intestinal disorder precludes the use of enteral formulations, for example, in cases of malabsorptive diarrhea. The total nutrient mixture is formulated from a mixture of lipid and dextrose supplemented with amino acids, electrolytes, water-soluble vitamins, minerals, and enough fluids to meet daily fluid volume requirements. Depending on the osmolarity of the solution, parenteral nutrition solutions can be delivered via a central, peripheral, intraosseous, or intraperitoneal catheter; however, the relatively high protein requirements of ferrets usually result in a solution of 600 to 800 mOsm/L, which should be administered into a large (central) vein.54

Ferret owners often prepare homemade diets of “duck soup” or “chicken gravy” to nurse their pets at home. Many different recipe variations are available online. These recipes are usually based on canned dog food, kibble, or whole chicken with additives ranging from beef fat, nutritional supplement gels, or brewer’s yeast to Echinacea capsules. The “duck soup” variations all provide a soft, porridge-consistency food that is usually readily eaten by sick and convalescing ferrets. Although many of these recipes appear to be acceptable, some are very high in fat and carbohydrates. Unless the homemade diets are based on or used with a commercial ferret diet, they should not be used long term because of possible nutritional imbalances and deficiencies. Discuss any particular recipe that a ferret owner is using before endorsing it for long-term use.

Urine Collection and Urinalysis

Urine samples can be collected by cystocentesis or by free catch after natural voiding or gentle manual expression of the bladder. The techniques for manually expressing the bladder and cystocentesis are the same as those used in dogs and cats. Anesthetize fractious ferrets to avoid trauma to the thin bladder wall. Use a 25-gauge needle for cystocentesis.

Reference values for urinalysis are listed in Table 2-4 . In one study, the reference range for urine pH in ferrets was reported as 6.5 to 7.5; however, urine pH can vary according to the diet, and the normal urine pH in ferrets fed a high-quality, meat-based diet is approximately 6.0.

Table 2-4.

Reference Values for Urinalysis in Ferrets

| Value | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL/24 hr) | 24.9 ± 14.319 | |

| Males | 2637 | 8-4837 |

| Females | 2837 | 8-14037 |

| pH | 6.5-7.537 | |

| Urine protein (mg/dL) | ||

| Males | 7-3337 | |

| Females | 0-3237 | |

| Exogenous creatinine clearance (mL/min/kg) | 3.3 ± 2.219 | |

| Insulin clearance (mL/min/kg) | 3.0 ± 1.819 | |

| Endogenous creatinine clearance (mL/min/kg) | 2.5 ± 0.919 |

Urinary Catheterization

Urinary catheterization is commonly indicated in male ferrets, but the procedure can be challenging. Although techniques have been described for both sexes,34 clinical indications to place a urinary catheter in females are rare. For females, tranquilize or anesthetize the ferret, then position it in ventral recumbency with the rear quarters elevated with a rolled towel. With a vaginal speculum, locate the urethral opening in the floor of the urethral vestibule, approximately 1 cm cranial to the clitoral fossa. Introduce a 3.5-French, red rubber urethral catheter fitted with a wire stylet into the urethral orifice.

In male ferrets, urethral blockage is a common sequela of adrenal disease. Androgens produced by the adrenal gland stimulate the prostate gland to enlarge, which subsequently constricts the urethra. Placing a urinary catheter is difficult because the urethral opening is very small and located on the ventral surface of the penis, below the J-hook in the end of the os penis. Also, in ferrets with urethral blockage, the tip of the penis and the preputial area are often very swollen, and introducing a catheter can be challenging. If needed, a small incision can be made in the prepuce to facilitate exteriorizing the penis. Surgical magnifying loupes may be helpful in locating the urethral orifice.

To place a catheter, use a 3.0-French polytetrafluroethylene urinary catheter (Slippery Sam Tomcat Urethral Catheters, Surgivet, Smiths Medical, Norwell, MA; Ferret Urinary Catheter, Mila International, Erlanger, KY) or a 3.5-French rubber feeding catheter (see also Chapter 4). If using a long rubber catheter, estimate the length of the catheter that must be inserted to reach the bladder before placing it. Use a stylet or flexible KE wire to stiffen the catheter while passing. Another option is to use a 20- or 22-gauge, 8-inch jugular catheter with the stylet removed.46 If needed, the stylet can be left in but retracted slightly to provide stiffness, but be very careful when rounding the pelvic flexure to avoid perforating the urethra. Use sterile technique to prepare the urethral and preputial area and pass the catheter. If the urethral opening is difficult to see, dilate the opening by passing a 24-gauge intravenous catheter just inside the tip of the urethra and flushing gently with saline. Then slip the tip of the lubricated urinary catheter gently into the dilated opening alongside the intravenous catheter and, while gently flushing with saline solution, pass the catheter into the bladder. Often resistance is met at the pelvic flexure; if this occurs, try repeated gentle flushing and relubricating the catheter until it passes. Once in place, secure the catheter by suturing the hub to the prepuce if using a Slippery Sam catheter. If using a rubber catheter, place butterfly tape strips around the catheter just as it enters the urethra and at another point 3 to 5 cm distal and suture these to the skin. Attach a sterile urinary collection device, and tape the tubing to the tail to further prevent tension. If needed, bandage the ferret’s abdomen to minimize rotation of the catheter and to restrict the ferret from traumatizing it. Soft Elizabethan collars are needed in some ferrets to prevent chewing at the catheter. Maintain sterility of the collection system, and drain the bag by needle and syringe rather than opening the system (see also Chapter 4).

Temporary tube cystostomy has been used successfully to manage male ferrets with urinary obstruction caused by adrenal disease. In four ferrets treated surgically, a 5- or 8-French Foley catheter was placed in the bladder at the time of adrenalectomy and left in place for 5 to 14 days.44 In these ferrets, immediate treatment of urinary blockage was by cystocentesis. A cystostomy catheter also can be placed by interventional radiographic techniques. This is an important option in obstructed ferrets in which a urethral catheter cannot be passed and surgery is considered high risk because of the poor condition of the patient. A cystostomy catheter allows azotemic ferrets to be managed with diuresis before surgery; alternatively, in cases in which surgery is not an option, the catheter can remain in place until response to medical management with leuprolide acetate occurs.

Splenic Aspiration

Splenic aspiration is a common diagnostic technique that is used in ferrets with enlarged spleens (see Chapters 5 and 36Chapter 5Chapter 36). The technique is simple and usually can be done in unanesthetized ferrets. However, if a ferret is fractious, use an injectable sedative or inhalant anesthesia administered by face mask. Restrain the ferret on its back or in lateral recumbency, and shave and prepare the abdominal skin in the area over the spleen. Palpate and immobilize the spleen directly under the prepped area with one hand while inserting a 25-gauge needle into the spleen several times with the other hand. Then attach an air-filled syringe to express the contents of the needle onto slides. This technique will minimize blood contamination. Alternatively, attach a 25-gauge needle to a 3-mL syringe and aspirate quickly after directing the needle into the spleen. A positive aspirate appears bloody. Detach the needle, fill the syringe with air, and express the samples onto slides. Obtain samples from two sites and prepare several slides for cytologic staining. If an abnormal mass is found on ultrasound examination, perform an ultrasound-guided aspirate to improve chances of a positive result. The two most common findings on cytologic examination of a splenic aspirate are extramedullary hematopoiesis and lymphoma.

Bone Marrow Collection

Evaluating a bone marrow sample is a valuable diagnostic tool for many disease conditions, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, proliferative abnormalities, and suspected hematopoietic malignancies. Anesthesia is necessary to aspirate the bone marrow or perform a core biopsy.

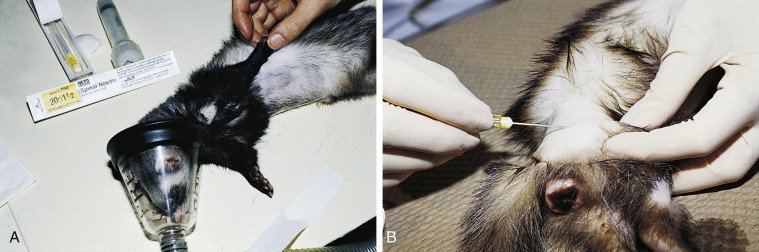

Although the proximal femur is usually the most readily accessible site, the iliac crest, tibial crest, and humerus can also be used to collect bone marrow samples (Fig. 2-5 ). After the ferret is anesthetized, place it in lateral recumbency and shave and aseptically prepare the area around the collection site. For the proximal femur,50 make a small incision through the skin over the greater trochanter with a no. 15 scalpel blade. Hold and stabilize the femur with one hand while inserting a 20-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle into the bone medial to the greater trochanter. Use steady pressure and an alternating rotating motion to advance the needle into the marrow cavity. Withdraw the stylet, and attach a 6- to 12-mL syringe to the needle. Aspirate the marrow sample into the syringe, stopping suction as soon as the sample is visible (to prevent blood contamination). To collect a core biopsy sample, use the same technique, but use a 1.5-inch, 18-gauge needle in place of the spinal needle.63 Collect samples from alternate sites by using the same basic technique.

Fig. 2-5.

A, Preparing to collect a bone marrow sample from the humerus of a ferret. The site over the proximal humerus is shaved and aseptically prepared. B, Collection of a bone marrow sample from the femur of a ferret with an enlarged vulva. The femur is stabilized while inserting a 20-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle medial to the greater trochanter.

Try to prepare at least four to eight slides for cytologic evaluation. To do this, forcibly expel the bone marrow sample from the syringe onto glass slides. The slide can be held vertically to allow contaminating blood to drain, leaving only bony spicules. Place a clean slide on top of the slide with the sample and allow the marrow to spread between the slides, then draw the two slides apart in a horizontal plane.63

Tracheal Wash

Ferrets will occasionally have clinical and radiographic evidence of respiratory disease. In these animals, a tracheal wash may be indicated to obtain samples for cytologic examination and bacterial culture and sensitivity testing. The procedure is similar to that used in a cat. Anesthetize the ferret and intubate with a sterile endotracheal tube. An 8-French pediatric suction catheter (Safe-T-Vac Suction, Kendall Healthcare Products, Mansfield, MA) connected to a specimen container (Argyle Lukens Specimen Container, Sherwood Medical, St. Louis, MO) and attached to a wall suction outlet will maximize the volume of sample collected. Pass the tip of the suction catheter through the endotracheal tube, preferably to the level of tracheal bifurcation. Inject up to 2 mL of warm, sterile saline solution, then aspirate the fluid into the specimen container.

Blood Transfusion

Blood transfusions may be needed in ferrets that are anemic from chronic disease, blood loss, or estrogen toxicosis or in ferrets that are thrombocytopenic. As in other species, evaluate the need for a transfusion based on the packed cell volume or platelet count and clinical status of the ferret. Consider a transfusion if the packed cell volume is 25% or less in a ferret that exhibits clinical signs of anemia or requires surgery or if a ferret is thrombocytopenic and exhibits ecchymosis, petechiation, or bleeding.

Ferrets lack detectable blood groups and there is little risk of transfusion reaction, even without cross-matching.33 Because they have a larger blood volume, large male ferrets are preferred over females as blood donors. Depending on the size of the donor ferret, 6 to 12 mL of blood can be safely collected for transfusion. Collect blood into an anticoagulant such as acid-citrate-dextrose at a ratio of 1 mL of anticoagulant to 6 mL of donor blood.24 Always use a filter when transfusing whole blood, and use at least a 22-gauge catheter (to prevent cell lysis). Intraosseous blood transfusions can be given to ferrets if an intravenous catheter cannot be placed.

Use of a hemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solution obviates the need for a donor ferret and a filter for administration, and the solution can be administered through a catheter of any size. A hemoglobin-based oxygen-carrying solution (Oxyglobin, Biopure Corp., Cambridge, MA) has been used in anemic ferrets at a dose of 11 to 15 mg/kg infused over a 4-hour period and administered once or twice during a 24-hour period.48., 49. However, this product is currently unavailable.

Blood Pressure Monitoring

Indirect blood pressure monitoring techniques in ferrets, using both Doppler ultrasound and oscillometric methods, have been described.30., 45., 56. However, both methods have shown poor correspondence with direct arterial blood pressure measurements. In one study using 10 healthy adult female ferrets to compare direct blood pressure measurement from the carotid artery to indirect blood pressure measurement from the tail and limbs using both Doppler and oscillometric methods, the indirect systolic blood pressure measurements were approximately 28 to 30 mm Hg less than the direct systolic blood pressures. Accurate indirect blood pressure readings were deemed very difficult to obtain because the neonatal blood pressure cuff did not fit securely on the short limbs of the ferrets (Doppler method) and the tail artery did not produce sufficiently high pressure changes to be detected by the oscillometric system. The authors concluded that indirect blood pressure assessment, using a sphygmomanometer and Doppler probe, could still be considered useful for evaluating changes in blood pressure from a known baseline or for surgical monitoring of general trends.45 In another study using 14 male ferrets, indirect blood pressure measurements using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer and a veterinary high definition oscillometry monitor on the tail, forelimb, and hindlimb were compared with direct arterial blood pressure measurements. Measurements using the tail were considered most reliable; however, the oscillometric sphygmomanometer consistently overestimated the systolic arterial pressure. In addition, the indirect measurements of systolic, mean, and diastolic arterial pressures obtained with the high-definition oscillometry monitor were consistently higher than the corresponding direct blood pressure measurements during hypotensive states but were substantially lower than the corresponding direct blood pressure measurements in hypertensive states.56 Therefore, be aware of the above described inconsistencies of indirect methods when compared with results of direct blood pressure measurement, and interpret clinical results to measure trends more than for accurate measurements.

In clinical practice, the Doppler method of indirect blood pressure measurement is most commonly used in ferrets and other small mammals. Shave the hair on the ventral carpus or tarsus (overlying the radial artery on the front leg or the digital branch of the tibial artery on the rear leg), and place the ferret in lateral or sternal recumbency. Place a pneumatic cuff (infant or number 1) above the carpus or tarsus or on the distal humerus, and attach it to a sphygmomanometer. Place the Doppler transducer probe crystal on the shaved skin in a bed of ultrasonic gel and tape or hold in place. Inflate the cuff bladder to a pressure exceeding the systolic blood pressure, which will diminish the Doppler signal of blood flow. Deflate the blood pressure cuff gradually; the first sound heard denotes the systolic pressure.30 Normal systolic blood pressure in ferrets is similar to that of other small mammals (80 to 120 mm Hg).

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

Ferrets are commonly presented for disease involving the abdominal cavity. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage has been widely used in human and veterinary medicine for assessment of abdominal fluid accumulation secondary to organ rupture, hemorrhage, and neoplasia. In humans, diagnostic peritoneal lavage is a more sensitive diagnostic test than abdominocentesis, and less fluid is required for diagnosis. In dogs and cats, accuracy of diagnosis is higher with diagnostic peritoneal lavage than with abdominocentesis.51

The technique described in ferrets is similar to that used in dogs and cats.51 Anesthetize or sedate the ferret, depending on the stability of the patient. Place the ferret in dorsal recumbency to facilitate identification and retraction of the spleen, and, if possible, empty the urinary bladder. Shave and aseptically prepare the skin caudal to the umbilicus, retracting the spleen as necessary. Infuse the skin and body wall at the entry site with 2% lidocaine, and make a small stab incision through the skin. Elevate the body wall with sterile forceps, and inset an 18- to 20-gauge over-the-needle catheter through the body wall, being cautious to avoid the spleen. The catheter can be sterilely fenestrated before insertion to optimize fluid recovery; however, take care to remove all cut pieces. Advance the catheter caudodorsally, and remove the stylette. Aspirate the catheter; if no fluid appears, instill 20 to 22 mL/kg of warm sterile isotonic saline. Rock the ferret gently or massage the abdomen for 1 to 2 minutes. Aspirate the fluid and place into sterile containers for evaluation. If necessary, repeat fluid instillation at up to half the initial volume used. Remove the catheter, and suture or glue the incision. Treat with a systemic analgesic subsequent to the procedure.

References

- 1.Abe N., Tanoue T., Noguchi E. Molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis isolates from domestic ferrets. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:733–736. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appel M.J., Harris W.V. Antibody titers in domestic ferret jills and their kits to canine distemper virus vaccine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;193:332–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell J.A. Parasites of domesticated pet ferrets. Compend Cont Educ Pract Vet. 1994;16:617–620. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell J.F., Moore G.J. Susceptibility of carnivore to rabies virus administered orally. Am J Epidemiol. 1971;93:176–182. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson K.G., Paul-Murphy J., Carr A. Percutaneous placement of a gastric feeding tube in the ferret. Lab Anim. 2000;29:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson K.G., Paul-Murphy J., Hart A.P. Coagulation values in normal ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) using selected methods and reagents. Vet Clin Pathol. 2008;37:286–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2008.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blancou J., Aubert M.F.A., Artois M. Experimental rabies in the ferret (Mustela [putorius] furo): susceptibility—symptoms—excretion of the virus. Rev Med Vet. 1982;133:553–557. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleakley S.P. Simple technique for bleeding ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) Lab Anim. 1980;14:59–60. doi: 10.1258/002367780780943123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown S.A. Clinical techniques in domestic ferrets. Sem Avian Exot Pet Med. 1997;6:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caligiuri R., Bellah J.R., Collins B.R. Medical and surgical management of esophageal foreign body in a ferret. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;195:969–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll E.E., Dubielzig R.R., Schultz R.D. Cats differ from mink and ferrets in their response to commercial vaccines: a histologic comparison of early vaccine reactions. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:216–227. doi: 10.1354/vp.39-2-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castanheira de Matos R.E., Morrisey J.K. Common procedures in the pet ferret. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2006;9:347–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cathers T.E., Isaza R., Oehme F. Acute ibuprofen toxicosis in a ferret. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216:1426–1428. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.1426. 1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Church R.R. Impact of diet on the dentition of the domesticated ferret. Exot DVM. 2007;9:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control, 2008 National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians. www.nasphv.org/documentsCompendia.html Available at. Accessed January 31, 2011. [PubMed]

- 16.Court M.H. Acetaminophen UDP-glucuronosyltransferase in ferrets: species and gender differences, and sequence analysis of ferret UGT1A6. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2001;24:415–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2885.2001.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodds W.J. Rabbit and ferret hemostasis. In: Fudge A.M., editor. Laboratory medicine: avian and exotic pets. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eshar D., Wilson J. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in ferrets. Lab Anim. 2010;39:339–340. doi: 10.1038/laban1110-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteves M.I., Marini R.P., Ryden E.B. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate and evaluation of renal function in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher P.G. Esophagotomy feeding tube placement in the ferret. Exot DVM. 2001;2:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox J.G. Normal clinical and biologic parameters. In: Fox J.G., editor. Biology and diseases of the ferret. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1998. pp. 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fudge A.M. Ferret hematology. In: Fudge A.M., editor. Laboratory medicine: avian and exotic pets. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harms C.A., Sladky K.K., Horne W.A., Stoskopf M.K. Epidural analgesia in ferrets. Exot DVM. 2002;4.3:40–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoefer H.L. Transfusions in exotic species. In: Hohenhaus A.E., editor. Transfusion medicine. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1992. pp. 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson-Delaney C.A. Diagnosis and treatment of dental disease in ferrets. J Exot Pet Med. 2008;17:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko J., Marini R.P. Anesthesia and analgesia in ferrets. In: Fish R.E., Danneman P.J., Brown M., editors. Anesthesia and analgesia in laboratory animals. 2nd ed. Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier; San Diego: 2008. pp. 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee E.J., Moore W.E., Fryer H.C. Haematological and serum chemistry profiles of ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) Lab Anim. 1982;16:133–137. doi: 10.1258/002367782781110241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lennox A.M. Intraosseous catheterization of exotic animals. J Exot Pet Med. 2008;17:300–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennox A.M. Post-surgical hyperthermia in ferrets. Proc Assoc Exot Mam Vet. 2009:9–10. www.aemv.org/documents/AEMV2009ScientificSession.pdf Available at. Accessed March 5, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichtenberger M., Ko J. Critical care monitoring. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2007;10:317–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis J.H. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. Comparative hemostasis in vertebrates. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann P.H., Harper D.S., Regnier S. Reduction of calculus accumulation in domestic ferrets with two dentifrices containing pyrophosphate. J Dent Res. 1990;69:451–453. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning D.D., Bell J.A. Lack of detectable blood groups in domestic ferrets: implications for transfusion. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;197:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marini R.P., Esteves M.I., Fox J.G. A technique for catheterization of the urinary bladder in the ferret. Lab Anim. 1994;28:155–157. doi: 10.1258/002367794780745191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marini R.P., Jackson L.R., Esteves M.I. Effect of isoflurane on hematologic variables in ferrets. Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:1479–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayer J. Use of behavior analysis to recognize pain in small mammals. Lab Anim. 2007;36:43–48. doi: 10.1038/laban0607-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer E.K. Vaccine-associated adverse events. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2001;31:493–514. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(01)50604-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]