Abstract

Textile materials, including natural and synthetic fibers, are good media for growth of microorganisms, particularly the drug-resistant bacteria, which have caused great concern to public health. Biocidal properties should be a necessary feature for medical-use textiles. Biocidal functions, different from biostatic functions, include sterilization, disinfection, and sanitization in an order of the strength. According to guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), medical use biocidal functions should be at least at the disinfection level, which can inactivate most infectious microorganisms. In addition, biocidal functions on textile materials should survive repeated laundering if used as uniforms, linens and even reusable surgical scraps and gowns. Among the currently investigated antimicrobial materials, only N-halamines have shown the capability of providing fast and total kill against a wide range of microorganisms without causing resistance from microorganisms. Furthermore, halamine structures can be recharged by chlorine bleaching, a process recommended by CD as well. Thus, biocidal textiles containing the halamine structures have been developed. Recent studies in biocidal polymers have resulted interesting progresses in incorporating halamines to all synthetic fabrics that are widely used as medical and other professional clothing materials. Chemistry and properties of the new processes have been discussed in this presentation.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years protection of healthcare workers from cross-transmission of infectious diseases, particularly blood borne viruses such as HIV and Hepatitis B, has become extremely urgent and important to medical professionals l-2. Medical protective gear for doctors and nurses including gowns, masks, and gloves are currently serving as barriers to the diseases and are insufficient in preventing the transmissions of the diseases. Recent outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) have further indicated that the barrier materials may not be able to provide sufficient protections against this disease since a large number of SARS patients are healthcare workers. In addition, researchers have revealed that textiles are good media for hosting microorganisms and therefore, are potentially responsible for the disease transmission 3. Moreover, spreading of multidrug-resistant bacteria in healthcare facilities is threatening not only safety of healthcare workers but also publics. One drug-resistant microorganism, mecicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was found not only existing but also surviving for a long period of time on all of textile materials in hospital environment 3–5. No doubts, textile materials are responsible for disease transmission and spreading of the new strains of the diseases from the main sources to elsewhere 3. On the other side, textile materials, as necessary materials for clothing and daily life, are possible means for prevention of infectious diseases and pathogens, if they become antimicrobial. Thus, the research and development of antimicrobial textiles, particularly the medical textiles for healthcare providers and patients are important and necessary.

MEDICAL USE TEXTILES

What are the ideal protective textiles for medical workers? A quick and brief answer is antimicrobial textiles, or more specifically the biocidal textiles. The biocidal materials are able to kill and eliminate the growth of microorganisms, and can therefore protect wearers of the textiles from biological attacks. Biocidal functions are completely different from biostatic functions that only inhibit the growth of microorganisms on textiles. Biostatic functions are usually employed in preservation of textile arts in museum or odor-control of the materials, but cannot prevent transmission of diseases due to the limitation of functions.

It is commonly believed that the ideal biocidal textile materials for medical use should posses the following features: 1) rapid inactivation of a broad spectrum of microorganisms; 2) non-selective and non-immutable to pathogens; 3) non-toxic and environmentally friendly; 4) durable to repeated washes; and 5) easy to be recharged in laundering or disinfection processes. In addition, the recharging agents should be non-toxic, available at home, and compatible with our laundering chemicals such as detergents or bleaching agents. Antimicrobial textile material was first developed in 1867 by Lister who demonstrated the relationship between fibrous materials and diseases 6. Since then, many innovative antimicrobial materials have been developed 7–10.

Rechargeable biocidal functions

In 1962 Gagliardi proposed a model in making antimicrobial textiles, named regeneration principle11. Although the model was presented over thirty years ago, there has been little reported success in textiles until recently. However, this principle has provided an important approach in the design of this innovative functional finishing. Antimicrobial functions on textiles, different from other functional finishes on textiles, normally consume biocidal agents incorporated into fibres. Therefore, to achieve durable and rechargeable antimicrobial functions reversible reactions and house-hold recharging agents were considered in this research.

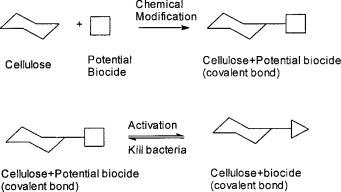

Chlorine bleach is a registered biocide and has been used as a disinfectant for decades without any reported resistance generated from any microorganisms. But, it is quite corrosive and toxic, particularly with concerns of producing carcinogens (such as HCCl3) in water. However, some of chlorine derivatives, i.e. halamine compounds, though possessing similar biocidal properties as chlorine, are more environmentally friendly and thus widely used in swimming pools and even drinking water disinfection 12–13. Halamines inactivate microorganisms by oxidation mechanisms rather than biological functions, and wide usage of them could result in less concern on drug-resistance of diseases. If the halamine compounds can be covalently connected to polymers, a reversible redox reaction can then be implemented on solid materials. The design of modification of textiles, activation or regeneration of halamine structures, and inactivation of microorganisms is expressed by a regeneration principle (Fig. 1 )14–15.

Figure 1.

Regeneration principle14

(Reproduced from reference 14, copyright American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists)

According to the mechanism of the biocidal function and regeneration process, diluted chlorine bleach solutions serve as both activation and regeneration agents of the biocidal functions. By using the chlorine bleaching process, the potential biocidal groups grafted on cellulose, i.e. amide or imide N-H bonds in hydantoin rings, will be converted to biocidal halamine structures, meanwhile the textiles materials are sterilised. It provides a convenient way for activation and regeneration of biocidal functions, and is the best fit for medical use textiles since they are commercially laundered with chlorine bleach. Many of these halamine structures have been reviewed and investigated for water disinfection purposes 12. Recent development of halamine polymers has brought in many applications of the chemical equations 13.

Monomethylol or dimethylol derivatives of 5,5-dimethyl hydantoin were first employed in grafting the heterocyclic ring to cellulose 14–15. When chlorine atom replaces hydrogen on N-H bond, the N-Cl bond is formed and stabilised by the vicinal carbonyl groups on the grafted dimethyl hydantoin ring (Fig. 2 ). The stability of N-Cl bonds on halamines contributes to the durability and stability of antimicrobial properties on chlorinated fabrics, with evidence that the bleached fabrics could retain the antimicrobial properties for more than six months in conditioning room (at 21'C and 65% relative humidity). After each laundering, the fabrics treated with dimethylo 1-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (DMDMH) or monomethylo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (MDMH) could be recharged by chlorine bleaching because of presence of predominant imide N-Cl bonds that can be washed off by detergents (reverse reaction in Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial finishing on cellulose 14–15Rechargeable biocidal finishing of cellulosic fabrics

The antibacterial properties of the finished fabrics were evaluated with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungus, yeasts, and viruses following AATCC standard test method 100. These microorganisms represent a whole spectrum of pathogens that healthcare providers are encountering every day. Based on characteristics of medical protection requirements, contact time of microorganisms on surfaces of fabrics was chosen at two minutes, which was the shortest interval when a microbiological test can be managed properly. Two commonly used fabrics, pure cotton and polyester/cotton sheets, were treated by finishing solutions containing 2% and 6% of dimethylol dimethylhydantoin (DMDMH), respectively, and bleached subsequently in a diluted chlorine solution. The results, listed in Table 1 , are reported in log reductions of microorganisms, with one log reduction referring to 90% kill and three log reduction meaning 99.9% kill. Comparing to other antimicrobial textiles, the new biocidal fabrics exhibited superior properties as textile materials for medical workers and patients, owing to their rapid and effective inactivation of a broad range of microorganisms. In addition, the outstanding biocidal properties of the fabrics are durable and regenerable by chlorine bleaching, a process commonly used in commercial laundering of institutional textiles. The antimicrobial properties of the fabrics could be recharged after repeated laundering by the bleaching. Apparently, active chlorine in halamines could be affected by laundering detergents. Thus, after each laundry the fabrics are recommended be bleached to refresh the lost antimicrobial functions. Chlorine bleaching is a required process for used medical textiles, and using it in medical textiles is compatible with the existing operation. More recently, durable and regenerable

Table 1.

Biocidal results of fabrics treated by 2% and 6% of DMDMH 15

| Fabric* | Microorganism | Log Reduction of Bacterial Challenge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2% DMDMH | 6% DMDMH | ||

| Cotton | E. coli | 6 | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | 6 | 6 | |

| Cotton | Staph. aureus | 6 | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | 6 | 6 | |

| Cotton | Salmonell | 6 | 7 |

| Cotton/PET | choleraesuis | 7 | 6 |

| Cotton | Shigella | 6 | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | 6 | 7 | |

| Cotton | Candida albicans | 2 | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | 6 | 6 | |

| Cotton | Brevibacterium | 8 | 8 |

| Cotton/PET | 8 | 8 | |

| Cotton | Pseudomonas | 6 | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | aeruginosa | 6 | 6 |

| Cotton | Methicillin-resis. | / | 3 |

| Cotton/PET | Staph. aureus | / | 6 |

| Cotton | Vancomycin resis. | / | 6 |

| Cotton/PET | Enterococcus | / | 6 |

AATCC test method 100. contact time: 2 minutes.

plain woven pure cotton fabric and polyester/cotton (65/35) plain woven fabric. (Reproduced from reference 15, copyright American Chemical Society)

antimicrobial fabrics that can survive more than 50 machine washes without recharging have been developed by using the same chemistry.

Rechargeable biocidal finishing of textiles

N-halamine structures have been incorporated into cellulose-containing and nylon fabrics by a conventional finishing method in the presence of formaldehyde16–19.

Recently, a hydantoin-containing monomer, 3-allyl- 5,5-dimethylhydantoin (ADMH, as shown in Fig. 3 ) was prepared to incorporate the same hydantoin rings into textiles16–17. Due to the allyl structure, ADMH forms its own homopolymer with difficulty, making it a good choice in grafting polymerisation, where the formation of homopolymers, which could consume as much as 80% of the monomers added, should be minimised 16–19. By using radical initiators such benzoyl peroxide (BPO) and potassium persulphate (PPS), macroradicals could be generated on most synthetic and natural fibres. The macroradicals can then undergo radical addition reactions with ADMH. As a result, ADMH could be grafted onto cotton, cotton/polyester, nylon, polypropylene, and even high performance fabrics such as Nomex and Kevlar.

Figure 3.

Controlled radical grafting reaction on fibres 19

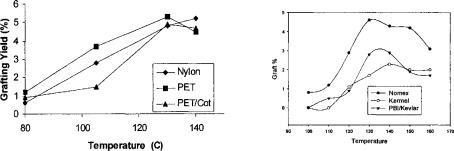

Most of the radical grafting reactions also need triallyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione (TATAT) or poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylates (PEG-DIA) to increase grafting yields16. These are polyallyl or polyvinyl compounds, which can introduce crosslinking effect to the fabrics. The overall grafting reaction is controlled by carefully managing a combination of radical initiation on polymers over monomers, addition of macroradicals to monomers, and crosslinking effects from the additives. Fig 4 (a) and (b) show grafting add-on of monomers under different temperature on several fabrics.

Figure 4.

18–19 Grafting add-ons on Nylon, PET, and PET/Cotton (a) and Nomex, Kermel, and PBI/Kevlar (b). (a) ADMH 4%, TATAT 1.5%, softener 1.5%, and BPO 0.2% at 100% wet pick-up and dried at 50 C for 5 minutes, then cured for 5 minutes; (b) ADMH 3 %, PEG-DIA 2 %, softener 1.5%, and initiator 0.5%. 100% wet pick-up, dried at 50 0C for 5 min., cured at varied temperatures for 5 min.

ADMH grafted fabrics could provide similar halamine structures to the grafted fabrics, and result in desired antimicrobial functions (Tables 2 and 3 ). The functions can be recharged in chlorine bleaching. In fact, after 50 washes all fabrics could still regain their biocidal properties easily. Due to hydrophobicity of several polymers, the active halamine structures could not be washed off easily. Table 4 shows antimicrobial results of Nomex fabrics after repeated washing and recharge. The antimicrobial properties on the Nomex fabric survived fifteen times laundry with minimal reduction of efficacy. After 50 washes, a chlorine recharge can almost completely restore the lost chlorine on the fabric.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial properties of nylon, polyester and polyester/cotton18

| Fabric |

Add-on % |

Percentage Reduction of E. Coli at different Contact Time (min) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5* | 10 | 20 | 30 | ||

| Nylon | 4.8 | 99.9 | 99.999 | 99.9999 | 99.9999 |

| Polyester | 5.3 | No kill | 90 | 99.9 | 99.999 |

| Polyester/cotton | 4.9 | 99.99 | 99.999 | 99.999 | 99.999 |

AATCC test method 100. E. Coli concentration: 105 CFU /mL

Table 3.

Antimicrobial properties of Nomex, Kermel, and PBI/Kevlar19

| Fabric |

Add-on % |

Percentage Reduction of E. Coli at different Contact Time (min) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 30 | 60 | 120 | ||

| Nomex | 4.6 | UD | 99.9 | 99.9999 | 99.9999 |

| Kermel | 2.3 | UD | 90 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| PBI/Kevlar | 2.8 | UD | UD | 99.9 | 99.9* |

AATCC test method 100. E. Coli concentration: 106 CFU /mL

Table 4.

Washing durability and rechargeability of grafted Nomex fabric 19

| Washing time | Mei X 105 (Mol/g) | Bacterial Reduction of Nomex (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. aureus | ||

| 0 | 1.22 | 99.9999 | 99.9999 |

| 5 | 1.20 | 99.9999 | 99.9999 |

| 15 | 0.63 | 99.9999 | 99.999 |

| 30 | 0.27 | 99.9 | 99.99 |

| 50 | UD | 90 | 90 |

| 50 | 1.14 | 99.9999 | 99.9999 |

CONCLUSIONS

Durable and rechargeable antimicrobial textiles could be prepared with hydantoin derivatives by using two novel chemical treatments. The antimicrobial textiles produced with these technologies are biocidal materials that can provide rapid kill to a broad spectrum of pathogens, and the biocidal functions can be repeatedly recharged by chlorine bleaching. The chlorine bleaching is a required process for disinfection of medical use textiles. Therefore, this rechargeable biocidal textiles can be employed as medical textiles such as uniforms, patient dresses, bedding sheets and linens.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a CAREER award from the US National Science Foundation (DMI 9733981) and financially sponsored by HaloSource Corporation, Redmond, WA. US National Textile Center has provided partial financial support. The author acknowledges valuable supports from Drs. S.D. Worley, R. Broughton Jr., and Jeff Williams, and is in debt to Drs. Yuyu Sun, Xiangjing Xu, Louise K. Huang, and Lei Qian for their experimental work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binder S., Levitt A.M., Sacks J.J., Hughes J.M. Emerging infectious diseases: Public health issues for the 21 st century. Science. 1999;284:1311–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morse S.S. Factors in the Emergence of Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1995;1:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid0101.950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neely A.N., Maley M.P. Survival of enterococci and staphylococci on hospital fabrics and plastic. J of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38:724–726. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.724-726.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scudeller L., Leoncini O, Boni S., Navarra A., Rezzani A., Verdirosi S., Maserati R. MRSA carriage: the relationship between community and healthcare setting. A study in an Italian hospital. J of Hospital Infection. 2000;46:222–229. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackinnon M.M., Allen K.D. Long-term MRSA carriage in hospital patients. J of Hospital Infection. 2000;46:216–221. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lister J. On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery. Lancet. 1867;2(353):668. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigo T.L., Danna G.F., Goynes W.R. Affinity and Durability of Magnesium Peroxide-based Antibacterial Agents to Cellulosic Substrates. Textile Chemist and Colorist. 1999;31(1):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne J.D., Kudner D.W. A Durable Antiodor Finish for Cotton Textiles. Textile Chemist and Colorist. 1996;28(5):28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tweden K.S., Cameron J.D., Razzouk A.J., Bianco R.W., Holmberg W.R., Bricault R.J., Barry J.E., Tobin E. Silver Modification of Polyethylene Terephthalate Textiles for Antimicrobial Protection. ASAIO Journal. 1997;43:M475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutter C.N. The effectiveness of triclosan-incorporated plastic against bacteria on beef surfaces. J of Food Protection. 1999;62(5):474–479. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.5.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagliardi D.D. Antibacterial finishes. American Dyestuff Reporter. 1962 Jan. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worley, Williams S.D., Halamine D.E. Water disinfectants. CRC Critical Reviews in Environmental Control. 1988;18:133–175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Worley S.D., Sun G. Biocidal Polymers. Trends in Polymer Science. 1996;4:364–370. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun G., Xu X. Durable and regenerable antibacterial finishing offabrics. Biocidal properties. Textile Chemist and Colorist. 1998;30(6):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun G., Xu X., Bickett J.R., Williams J.F. Durable and Regenerab1e Antimicrobial Finishing of Fabrics with a New Hydantoin Derivative. Industrial Engineering Chemistry Research. 2001;41:1016–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y., Sun G. Novel Regenerable N-halamine polymeric biocides I: Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of hydantoin-containing polymers. J of Applied Polymer Sci. 2001;80:2460. 2457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y., Sun G. Novel Regenerable N-halamine polymeric biocides II: Grafting hydantoin-containing monomers onto cotton cellulose. J of Applied Polymer Sci. 2001;81:617–624. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y., Sun G. Durable and Regenerable Antimicrobial Textile Materials Prepared by A Continuous Grafting Process. J of Applied Polymer Sci. 2002;84:1592–1599. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y., Sun G. Novel Refreshable N-Halamine Polymeric Biocides: Grafting Hydantoin-Containing Monomers onto High-Performance Fibers by a Continuous Process. J of Applied Polymer Sci. 2003;88:1032–1039. [Google Scholar]