Publisher Summary

This chapter provides an overview of the biology and medical care of rabbits. There are about 50 different breeds of domestic rabbits. Rabbits have very thin and delicate skin that is covered with fine fur comprised of both a soft undercoat and stiff guard hairs. Care must be taken when clipping fur because the skin is prone to tearing. A rabbit enclosure should be large enough to provide a sleeping space, eating space, and latrine. Animals housed for long periods of time should also have ample room to exercise. The enclosure should be tall enough to allow the rabbit to sit up and not have its ears touch the top of the cage. Because rabbits are prone to heatstroke, they should be housed in temperatures ranging from 60°F to 75°F. If rabbits are housed outdoors, they must have access to shade and clean water, and the shelter should protect them from the elements as well as from predators. The ideal substrate for rabbits is grass hay; however, for indoor, caged rabbits, a foam rubber pad or a towel covered with newspaper and a thick layer of timothy hay can also be used.

Domestic rabbits, Oryctolagus cuniculus, belong to the order Lagomorpha, and their ancestors are from Western Europe and northwestern Africa.1, 2 Unlike rodents, lagomorphs have a second set of maxillary incisors directly caudal to the first set. Pet rabbits have unique, lively, and affectionate personalities that make them ideal pets for mature children and adults. Handling pet rabbits when they are young will likely make them more comfortable with humans later in life. In contrast, wild rabbits, no matter their age, do not become comfortable with human interaction. Rabbit owners commonly seek medical attention for their rabbits and husbandry guidance from veterinarians.

COMMON BREEDSKEPT IN CAPTIVITY

There are as many as 50 different breeds of domestic rabbits.3 However, many of the rabbits presented to private practice are mix breeds. Breed classification can be divided by size or fur type. The size classification is more helpful to the practicing veterinarian and can be divided into small breeds, less than 2 kg (e.g., Netherland dwarfs, lion head, mini-lop, and Dutch breeds); medium breeds, 2 to 5 kg (e.g., Rex, English, Angora, and Belgium hares), and large to giant breeds, more than 5 kg (e.g., New Zealand whites, English lops, British Giants, and Flemish Giants). The American Rabbit Breeders Association publishes information on the different breeds and various standards, and is an excellent resource for veterinarians (http://www.arba.net/).

Certain breeds are predisposed to health problems. For example, dwarf breeds, such as the Netherland rabbits, have short maxillae that make them more prone to nasolacrimal duct blockage and incisor malocclusion. In addition, dwarf breeds appear more susceptible to Encephalocytozoon cuniculi infections.2 Dutch, Havana, tan, and French silver breeds are more likely to develop uterine neoplasia.4 Because Rex rabbits have thin fur on the plantar surface of their feet, they are more susceptible to developing hock sores. Large and giant breeds are prone to developing arthritis and cardiomyopathies. British Giant and French lops are more likely to develop skin fold pyoderma under their dewlaps and in the perineum area, in addition to developing entropion.2

BIOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY

See Box 14-1 .

BOX 14-1. Physiologic Parameters for Captive Rabbits.

| Life span | 6-13 yr |

| Gestation | 30-32 days |

| Ages of weaning | 4-6 wk |

| Age of puberty | Small breeds 4-5 mo |

| Large breeds 5-8 mo | |

| Age of recommended neutering | Castration >3 mo, spay >5 mo |

| Temperature (rectal) | 37.8°-39.4° F (100°–103° F) |

| Heart rate | 130-325 beats/min |

| Respiratory rate | 32-60 |

Integumentary System

Rabbits have very thin and delicate skin that is covered with fine fur comprised of both a soft undercoat and stiff guard hairs. Care must be taken when clipping fur because the skin is prone to tearing. Unlike dogs and cats, rabbits lack footpads; instead, their feet are covered with thick coarse fur that protects the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet. Because they lack footpads, rabbits should be provided soft padded areas within their enclosures. Rabbits have nonretractable claws, making declawing an inappropriate procedure. Certain breeds of female rabbits have a dewlap, which is analogous to a second chin. Female rabbits may pluck fur from the dewlap during the breeding season to build a nest. Male and female rabbits may have three types of scent glands, including a single chin gland, paired inguinal glands, and paired anal glands. The glands are used to mark the rabbit's territory.

Sense Organs

Rabbits’ ears represent a large amount of the animals’ surface area. Because rabbits are low in the food web, these large ears serve an important function in assisting the animal with identifying potential predators. In addition, rabbits’ ears are highly vascularized and serve an important role in thermoregulation via vasoconstriction and vasodilatation.5 Rabbit ears are very sensitive and delicate and should never be used for restraint.

Rabbits have a wide field of vision, which is ideal for a prey species. With the lateral positioning of their eyes and their large corneas, rabbits have an overlapping field of vision of 190 degrees.3 Although rabbits are visually acute within this region, they cannot visualize items below the horizon, including the area below their nose. Instead, rabbits use their highly sensitive vibrissae and lips as tactile structures to distinguish food items. Rabbits possess good night vision and some color vision. Rabbits have functional third eyelids that partially close with sleep or while under anesthesia.5 A harderian gland is found at the base of the third eyelid. If this gland prolapses, then it may present as a mass under the third eyelid. Surgical intervention is recommended to replace the gland. Tear drainage from the eyes occurs via the nasolacrimal gland. There is a single lacrimal punctum located in the craniomedial aspect of the lower eyelid. The punctum empties into a cuniculus, leading to a lacrimal sac and continuing to the base of the maxillary incisor. At this point, the duct sharply changes direction, runs along the incisor root, and emerges in the nasal cavity in the ventromedial aspect of the alar fold.2 Blockage of this duct is common in captive rabbits. Affected animals may have unilateral or bilateral epiphora. Rabbits have a large retrobulbar orbital venous plexus. When an enucleation is performed, this venous plexus must be ligated to minimize hemorrhage.

Musculoskeletal System

Rabbits have a light skeleton surrounded by a very well-developed muscular system, which makes the vertebrae and long bones susceptible to fractures. To minimize the likelihood of injury, the hindlegs should always be supported when transporting the rabbit. The number of vertebrae varies between breeds, from 12 to 13 thoracic and 6 to 7 lumbar vertebrae.6 The epaxial and large muscles of the hindlimbs can be used for intramuscular injections.

Reproductive System

Female rabbits are classified as does, males as bucks, and neonates as kits. The onset of puberty occurs at approximately 4½ months of age; however, reproductive activity is generally dependent upon animal size, not age. In the dwarf breeds, sexual maturity occurs earlier than in larger breeds. The reproductive life of a rabbit is approximately 4 years.1 Rabbits are induced ovulators. Their receptivity periods last approximately 14 to 16 days, followed by 1 to 2 days of nonreceptivity.2 When females are ready to ovulate, they become restless, rub their chins, and assume a lordosis-like posture. Gestation lasts 31 to 32 days, and litters average 4 to 10 kits. As gestation or pseudopregnancy reaches the last 3 to 4 days, does initiate nesting behavior and line their nests with hair from the hip and dewlap.3 During this period, does consume less food, which can cause an increased risk for pregnancy toxemia. Parturition usually occurs in the early morning and lasts less than 30 minutes. Kits generally only suckle 1 or 2 times a day and are not usually seen with the doe, especially in the wild. Weaning occurs at approximately 4-6 weeks of age.

Does have two separate uterine horns and two cervices. Rabbits do not have a uterine body. The cervices open into the vagina, along with the urethra, to form one common urogenital opening. Bucks have a hairless scrotum. The inguinal rings of the buck are open, which allows the testicles to ascend and descend into and out of the abdomen. Male rabbits do not have an os penis or nipples.

Urinary System

The kidneys of rabbits are located in the retroperitoneal cavity, and their position in the body cavity is similar to that in cats. The kidneys are generally covered in fat and can be palpated on the physical examination. The urinary bladder is located in the ventral body cavity, and it is ventral to the colon. Rabbits, like rodents, have a unique system for calcium metabolism. Serum calcium is reflective of dietary calcium, and the urinary system is the primary site of calcium and magnesium excretion. Rabbits that consume a high calcium diet will often have thick and creamy urine due to the formation of calcium carbonate precipitate. On average, rabbits produce 30 to 35 ml of urine daily. Rabbit urine may be straw-colored, yellow, or red. It is not uncommon for rabbit urine to have a turbid appearance. When a rabbit presents with “red” urine, it is important to differentiate whether the urine has blood or porphyrins. Porphyrins can be produced as a result of the ingestion of various vegetables, such as beet root, cabbage, broccoli, and dandelions, or as a result of stress.2

Gastrointestinal System

Rabbits have open-rooted teeth that grow continuously throughout their lives at a rate of approximately 10 to 12 cm a year.1 The dental formula of the rabbit is 2 × (2/1 I, 0/0 C, 3/2 P, 3/3 M). Directly caudal to the maxillary incisors is a second pair of small incisors called peg teeth, whose function is to protect the palate from injury against the sharp surfaces of the lower incisors. The buccal surface of the upper incisors’ enamel is thicker and wears more slowly than the rest of the tooth, forming a chisel-like appearance. Caudal to the incisors is a space called the diasterna.7 The cheek teeth are located caudal to the diasterna and are responsible for macerating and grinding food.

Rabbits have simple, glandular stomachs. Due to the positioning and well-developed nature of the cardiac sphincter, rabbits are unable to vomit.8 Adult rabbits have a gastric pH of 1.5 to 2.2, whereas suckling rabbits have a higher pH of 5.0 to 6.5. The higher gastric pH in neonates is necessary for bacterial colonization of the intestinal tract. This elevated pH also makes suckling rabbits more susceptible to gastrointestinal disease. Dietary absences, especially during weaning, should be gradual, and foods high in sugars and starch should be avoided. Rabbits have a large cecum that acts as an anaerobic fermentation vat. The cecum has a complex and delicate population of microbes. The most common organisms found in the rabbit cecum are the Gram-positive Bacillus spp. In the cecum, fiber is broken down and separated. Rabbits are highly susceptible to antibiotic-induced enterotoxemia, especially when there is Clostridium spiriforme contamination in the environment. The rabbit's gastrointestinal tract is designed to eliminate fiber from the gut rapidly, in the form of hard feces, and digest the nonfiber portion of the diet, creating caecotrophs, which are reingested at a later time. Cecotrophs are covered with a thin mucus, which protects the volatile fatty acids, vitamins, and amino acids from the low pH of the stomach. Cecotrophs differ from feces in that they are soft, moist, usually stuck together, and are eaten directly from the anus.8 The gastrointestinal transit time in rabbits is approximately 20 hours. Rabbits offered a diet deficient in fiber usually have increased gastrointestinal transit times.

The pancreas is found within the mesentery along the lesser curvature of the stomach and extends to the right side of the abdominal cavity to the level of the duodenum. The rabbit pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions.

The rabbit liver has a caudate lobe with a narrow stalk, which can displace on occasion. Rabbits have a gall bladder, and the primary function of this structure is to store bile. The rabbit liver performs many of the same functions that the liver plays in the dog and cat.

Respiratory System

Rabbits are obligate nasal breathers. A rabbit that presents for open-mouth breathing generally has a guarded prognosis. The respiratory rate of the rabbit is approximately 30 to 60 breaths per minute. In a healthy animal, the nose will move up and down approximately 20 to 120 times a minute. The thoracic cavity of the rabbit is small in comparison to that of nonlagomorph or rodent mammals. Rabbit lungs have four right and two left lung lobes.3 Rabbits have an extremely narrow and long oral cavity. Because of these features, it can be difficult to visualize the glottis for intubation. Endoscopic examination provides the best visualization of the glottis for intubation. Inflammation of the upper respiratory tract increases the risk of anesthetic mortality in nonintubated animals.4

Cardiovascular System

Rabbits have a relatively small heart, and the average heart rate of the rabbit is 130 to 325 beats per minute.9 Systolic blood pressure is approximately 90 to 120 mmHg. The right atrioventricular valve has only two cusps, and the aorta rhythmically contracts.4 Rabbit veins are thin and susceptible to hematomas, so care must be taken with venipuncture.

HUSBANDRY

Environmental Considerations

ENCLOSURE SIZE

A rabbit enclosure should be large enough to provide a sleeping space, eating space, and latrine. Animals housed for long periods of time should also have ample room to exercise. The enclosure should be tall enough to allow the rabbit to sit up and not have its ears touch the top of the cage. In general, 3 square feet (sq ft) should be a minimum cage size for rabbits 2 to 4 kg, 4 sq ft for rabbits 4 to 4.5 kg, and larger rabbits require at least 5 sq ft.5 Rabbits housed in hutches and cages should be allowed a minimum of 4 hours of exercise daily.2 Indoor rabbits should be caged when they cannot be supervised, to decrease the likelihood of inappropriate chewing of carpet, electrical wire, or furniture. Cages should be cleaned daily to remove feces and urine. Gentle soap and hot water or a dilute bleach solution (1 : 32) should be used for cleaning. If bleach is used, then the cage should be cleaned in a well-ventilated area. Organic material should be removed before applying the bleach, to minimize the degradation of the bleach. The bleach or soap should have a minimum of 3 to 5 minutes of contact time on the cage to increase the killing potential of these products. It is important to clean, rinse, and dry off all detergents.

TEMPERATURE/HUMIDITY

Because rabbits are prone to heatstroke, they should be housed in temperatures ranging from 60° F to 75° F.2 If rabbits are housed outdoors, they must have access to shade and clean water, and the shelter should protect them from the elements as well as from predators. Rabbits are prone to developing fur and skin problems when housed in environments with high humidity; therefore, these animals should be provided environments with low to moderate humidity (30%-60%).

LIGHTING

Rabbits show a diurnal rhythm for eating, activity, and even hematologic variation. Most feeding takes place from after noon to evening. During foraging, rabbits commonly produce fecal pellets; in times of decreased intake, rabbits will actually ingest cecotrophs. In addition, hematologic parameters, such as the total white blood cell count, are lowest in the late afternoons and evenings. Although the eosinophils peak in early afternoon, the heterophils are highest in the late afternoon and early evening. Other changes can be seen with diurnal patterns, including changes in blood urea nitrogen, body temperature, and bile acid production.2 Because much of the rabbits’ behavior and physiology is regulated by diurnal patterns, it is important to provide a consistent light cycle. Although there are no specific lighting recommendations for rabbits, nonreproductive rabbits should be provided a 12-hour photoperiod, and breeding females should be provided 14 to 16 hours of light.10

SUBSTRATE

The ideal substrate for rabbits is grass hay; however, for indoor, caged rabbits, a foam rubber pad or a towel covered with newspaper and a thick layer of timothy hay can also be used.2 Avoid wood shavings, which contain oils that can lead to hepatotoxicity.2 Rabbits can easily be trained to use a litter box filled with straw, hay, or newspaper litter. It is important to keep any substrate clean and dry. If a rabbit is housed on a wire mesh floor, it is important that the mesh openings are no larger than 1 × 2.5 inches to prevent the feet from getting trapped and injured. In addition, it is also important to offer a solid, nonslip surface to provide rest off the mesh and prevent pododermatitis.4

ACCESSORIES

Most cat and bird toys can be used for rabbits. Because rabbits can chew these toys, it is important to be sure that they do not contain any toxins or small materials that can be ingested. Sticks or blocks of wood provide an excellent material for rabbits to file their teeth.

HOSPITALIZATION

In the veterinary hospital, rabbits should be housed in a cage with a nonslip surface on the bottom, such as a towel or thick bedding of fresh straw or hay. Rabbits should be hospitalized in a quiet, stress-free area within the practice, and protected from noises associated with dogs, cats, and ferrets. While in the hospital, rabbits should be offered fresh food and water, preferably what is being fed to them in their home environment. It is important to disinfect and dry the cage and accessories in contact with sick rabbits, using a dilute bleach, Roccal (Pfizer Animal Health, Kalamazoo, MI), or other hospital cleaner.

Nutrition

An average adult house rabbit should be offered ad lib grass hay, such as timothy, prairie, or oat brome; approximately 1 cup of leafy green vegetables; and, at most, ¼ cup of high-fiber (18%-22% to prevent obesity), low-protein (<18%) pellets per 2.2 kg (5 lbs) of body weight daily.4, 8 Examples of dark leafy greens include romaine lettuce, dandelion greens, Swiss chard, parsley, endive, kale, mustard greens, and carrot, beet, and turnip tops. Diets low in fiber, such as commercial, pelleted rations, may be associated with hypomotility, changes in the gastrointestinal pH and microflora, wool block from increased hair consumption, and cheek tooth overgrowth.7 Alfalfa hay should be avoided in adult animals, because of its high protein and calcium content, and instead, reserved for animals less than 6 months of age and for pregnant and lactating does with increased nutritional demands. When offering alfalfa hay to lactating does, slowly increase the amount over the first 5 days, as this will reduce the likelihood of milk overproduction and decrease the chance for the development of mastitis.4 Any diet change should be gradual.

Rabbits ingest cecotrophs formed from fermentation of nonfiber ingesta; these cecotrophs contain volatile fatty acids, vitamins, amino acids, and microorganisms. Cecotrophs are ingested straight from the anus; consuming them allows for absorption of these nutrients that would be lost otherwise. They are covered with a mucus that protects them from breakdown from stomach acids.

Chlorinated water should always be in fresh and ample supply. Rabbits are very sensitive to water deprivation and therefore should experience no restriction. Rabbits generally drink 50 to 100 ml/kg/day.2 Water should be offered in a nonleaking sipper bottle or in a heavy crock that cannot be tipped over. Rabbits that drink from crocks may develop “blue fur,” which is a moist dermatitis of the dewlap that is associated with Pseudomonas infections.

PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

There are no U.S.-approved vaccines for domestic rabbits. It is recommended that all house rabbits receive an annual physical examination, and as they become geriatric (>4 years), a biannual examination is recommended. In addition to the annual examination, a serum chemistry panel, complete blood counts (CBCs), and fecal exams for parasites are also recommended annually. Ovariohysterectomy or orchiectomy should also be recommended for all nonbreeding rabbits to decrease aggression, decrease the incidence of scent marking with urine and feces, and avoid unwanted pregnancy, pseudopregnancy, and neoplasia.

When adding new rabbits into an existing population, it is always recommended to quarantine the new additions for a minimum of 90 days. Separating new arrivals can decrease the likelihood of introducing infectious diseases and parasites to a standing population of rabbits. Before the rabbits are released from quarantine, they should have a CBC and chemistry profile done, and have 3 to 5 negative (2 weeks apart) fecal examinations consecutively. The client should be made aware that even a 90-day quarantine may be insufficient to detect some infectious diseases.

Rabbits' enclosures should be cleaned on a daily basis. Organic material should be removed before disinfectant is applied. Fresh substrate should be offered either daily or as it is soiled. The cage may be disinfected with mild soap and water or a dilute bleach solution (1 : 32). The disinfectant should have a minimum of 3 to 5 minutes of contact time to increase the effectiveness of the compound. The solutions should be thoroughly rinsed away, and the surface of the cage dried completely. Roccal D or chlorhexidine (Fort Dodge Inc., Fort Dodge, IA) can also be used to disinfect rabbit enclosures.

RESTRAINT

Manual Restraint

Rabbit physical restraint needs to be carefully performed to avoid injury to the animal. Because rabbits have a well-developed muscular system and thin cortical bone, they are subject to vertebral and long bone fractures if restrained incorrectly. Because most skeletal injuries associated with incorrect restraint occur in the lumbar vertebrae, it is important to firmly restrain the hindlegs. Rabbits should be handled in a manner similar to cats; place one hand on under the forelimbs, and use the other hand to hold the rear legs against the body. Always place the rabbit onto a nonslip surface to ensure that it has good footing. To restrain the animal, lightly scruff the animal and support its dorsum with the same arm. The opposite arm is used to support the body and rear legs (Figure 14-1 ). It can be helpful to tuck the head of the rabbit into the crook of one's elbow to decrease the rabbit's vision, which can decrease the stress on the animal. Placing a rabbit in dorsal recumbency evokes an immobility response, which can be helpful during simple procedures. However, this response is performed by prey species under stressful or threatening conditions and may not be welcomed by all rabbits (Figure 14-2 ). The immobility response is characterized by a lack of spontaneous movement and a failure to respond to external stimuli. This restraint technique should only be used in those cases where chemical sedation is not desired.2 A towel or blanket is usually necessary during the physical examination to cover the stainless steel exam table and to minimize slipping or kicking, which can lead to injury. In addition, a towel may be used to wrap the rabbit into a “bunny burrito” (Figure 14-3 ). The bunny burrito can be used to hold a rabbit for transport or to facilitate the examination of the head. Cat bags can also be used to restrain rabbits. In addition to using these techniques for examination, they can also be used to administer medication, collect blood samples, or perform nail trims.

Figure 14-1.

Proper restraint while transporting a rabbit. Notice the head is tucked in the crook of the elbow and the dorsum and feet are supported.

Figure 14-2.

Rabbits placed in dorsal recumbency will enter a trance-like state that may facilitate simple procedures, such as taking radiographs.

Figure 14-3.

Rabbits can be wrapped firmly in a towel making a “bunny burrito.” This technique can be used to facilitate an examination, nail trim, or other noninvasive procedure.

Chemical Restraint

Chemical restraint in rabbits should be used to decrease anxiety, and to provide sedation or immobilization for surgery. (The most common drugs used for premedication, sedation, and anesthesia are described later, in Anesthesia.) Isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) or sevoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) can be used to anesthetize rabbits; however, in high stress animals, a premedication is usually recommended.

PERFORMING A PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Before beginning the “hands-on” examination, observe the rabbit at rest, paying close attention to the animal's mentation, how the rabbit is holding its body, if it has signs of respiratory distress, its nose movements, its gait, and fecal and urine output. Very relaxed and very ill rabbits’ noses will be still. Note body condition for obesity, as well as signs of weight loss. When placing a rabbit on an exam table, be sure to offer it a nonslip surface such as a rubber mat or a towel. Routine physical exams should follow a thorough and consistent pattern, examining by system or from the head to the toes, being sure to examine everything in a similar manner to avoid overlooking a potential problem.

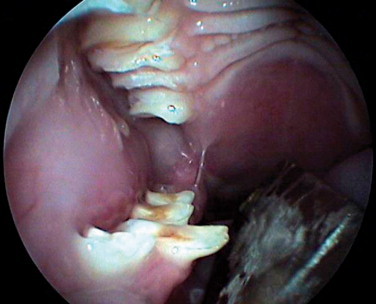

A thorough oral examination is an important component to any rabbit examination. Rabbits commonly present to the veterinarian with malocclusions of both incisors and cheek teeth. To examine the incisors, gently lift the lips for inspection. Be sure buccal surfaces are smooth (no horizontal ridges are present) and proper occlusion is met with mandibular incisors slightly caudal to the maxillary ones. A common noninvasive technique for examining the cheek teeth, which can be performed during every examination, is inserting an otoscope or vaginal speculum gently into the diasterna. Position the instrument caudally to visualize molars and premolars from both buccal and lingual surfaces (Figure 14-4 ). This technique does not provide the most thorough examination; however, it is relatively stress-free to the rabbit. If the rabbit is too stressed or uncooperative or a more thorough examination is necessary, lightly sedate the animal with an injectable sedative, or use isoflurane to get a better view. Once sedated, use a mouth speculum, mouth gag, or an endoscope to examine the molars (Figure 14-5 ). The most common locations for molar lesions are on the lingual surface of the mandibular cheek teeth and the buccal aspect of the maxillary teeth. The gingiva surrounding the molars should be at the level of the crowns except for the first mandibular cheek teeth in which the cranial aspect of the crowns will be more exposed. In addition to examining the teeth for overgrowth and malocclusion, it is important to inspect the oral mucosa and tongue for ulcerations and lacerations that may occur as a result of sharp points on teeth. The cheeks and jaws should be palpated for any swellings (e.g., abscesses) and the chin and dewlap examined for signs of drooling or slobbering. Abnormalities may be indicative of dental disease.

Figure 14-4.

An oral examination can be performed using an otoscope.

Figure 14-5.

An oral examination performed under sedation enables the veterinarian to perform a more thorough exam.

Rabbits should be given a thorough ophthalmic examination. Eyes should be closely examined for evidence of discharge, as ocular discharge is one of the most common ocular problems seen in veterinary practice. Purulent epiphora can be due to a variety of problems, including bacterial infection, corneal ulceration, a blocked nasolacrimal duct, or dental disease. The corneas should be clear and free from ulceration. A fluorescein stain should be done if ulceration is suspected. The anterior chamber should be examined closely. Hypopyon is a common finding in bacterial septicemia. The lens should be examined for clarity. Cataracts can occur as a result of congenital or traumatic causes. A fundic examination should be done to rule out retinal defects. Encephalitozoon cuniculi can cause retinal disease.

In addition to ocular discharge, it is important to evaluate the rabbit patient for nasal discharge. Rabbits are meticulous groomers and routinely use their front legs to clean their faces. Animals with nasal discharge routinely have secretions on their forelimbs. In rabbits, nasal discharge has been associated with upper respiratory infections, hypersensitivity (e.g., allergies), foreign bodies, and neoplasia.

An otoscope should be used to examine the ears on both sides of the tragus. Closely inspect the ears for evidence of pus, ceruminous discharge, and mites. With manipulation of the pinna and otoscope, it is possible to visualize deeper in the canal; however, it can still be difficult to visualize the tympanic membrane.

The legs should be palpated from a proximal to distal position. Limb fractures are common sequelae to inappropriate handling. Rabbits do not have footpads. Closely examine the plantar surface of feet for pododermatitis. Pododermatitis is a common problem in rabbits housed in metal-grate caging.

A rectal temperature should be taken during the examination. The body temperature of rabbits is generally between 100° F and 103° F (37.8° C to 39.4° C). To minimize the likelihood of measuring a falsely elevated temperature associated with stress, the body temperature should be collected early in the examination.

The integument should be thoroughly evaluated. Closely inspect the rabbit for alopecia or dandruff, especially near the shoulder blades. Palpate the mammary glands for abnormal masses. Mammary adenocarcinoma and mastitis are common findings in intact female rabbits. Evaluate the perianal area for urine scalding or fecal staining. This is very common in obese rabbits with redundant perianal tissue.

During the abdominal palpation, pay particular attention to the cranial left quadrant (e.g., stomach) and caudal lower quadrant (e.g., uterus, urinary bladder). A firm mass in the cranial abdomen may indicate a trichobezoar or delayed gastric emptying. A swelling or enlargement in the caudal quadrant of an intact doe may suggest pregnancy, pseudopregnancy, pyometra, or uterine adenocarcinoma. Cystic calculi can also occur and be palpated in the caudal abdominal quadrants.

Rabbits are obligate closed-mouth breathers. Open-mouth breathing in rabbits indicates an emergency situation. The heart and lungs should be ausculted. It is normal to hear the rapid movement of the air during inhalation and exhalation. These are usually referred to as sounds from the upper respiratory tract. An absence of these sounds can be associated with consolidation of the lungs. The respiratory rates of rabbits are generally more than 40 breaths per minute. The heart rate should be more than 180 beats per minute. To auscult the heart, place the stethoscope on the chest wall at the point of the elbow.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Rabbits are prey species and have evolved to mask their illnesses. It is imperative that veterinarians working with these animals develop a thorough diagnostic plan to ensure success with diagnosing and treating a case. The following is a review of common diagnostic tests performed on rabbits.

Clinical Pathology

Venipuncture should be done with care, as rabbit vessels are delicate and prone to hematoma formation. The maximum volume of blood that should be collected at one time is 1 ml/100 g body weight.9 Common sites for venipuncture include the jugular, lateral saphenous, cephalic and marginal ear veins. The jugular vein is the preferred site when a large sample is needed. To collect a jugular sample, the animal needs to be properly restrained. For restraint, a rabbit can be placed into a towel or a cat bag, and the neck gently extended in a manner similar to a cat; however, care should be taken not to extend the head too far. In some female rabbits, a large dewlap can reduce access to the jugular vein. Marginal ear veins can be used to collect blood samples with a 25- or 26-gauge needle. Generally, this site can only be used to collect small blood samples. This vein can also be used to place a catheter; however, catheterization can lead to vascular necrosis, thrombosis, and sloughing of the ear and should be avoided in breeds with small ears (e.g., dwarf breeds). The lateral saphenous vein is suitable for small- to moderate-sized blood samples (Figure 14-6 ). Placing alcohol over the venipuncture site or clipping the fur in that area can facilitate visualization of the vein. The cephalic vein can also be used to collect samples; however, this site is often reserved for intravenous catheter placement.

Figure 14-6.

Shaving the lateral hindlimb will facilitate visualization of, and access to, the lateral saphenous vein.

Hematology/Chemistry Panels

CBCs and serum chemistry panels should be performed in rabbits presenting for any disease process and as part of an annual exam. Rabbits have some unique hematologic differences in their CBC compared to other mammals. Healthy rabbits are primarily lymphocytic. Both small and large lymphocytes can be found in circulation. Rabbit lymphocytes are similar in appearance to this cell type in other vertebrates and are characterized by a deep blue cytoplasm, acentric nucleus, and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The acute inflammatory cell in rabbits is the heterophil. Although the function is similar to the neutrophil of other mammals, the staining characteristic of this cell type is different. Monocytes are the largest circulating white blood cell in rabbits and are characterized by diffuse nuclear chromatin, blue cytoplasm, and large, dark red granules in cytoplasm.9, 11 Eosinophils have large granules and a bilobed or horseshoe-shaped nucleus. Low-grade eosinophilia can be seen with chronic parasitism. Basophils are relatively common in rabbits and can represent up to 30% of the differential in healthy animals. Infections rarely cause elevated white blood cell counts (>15,000 cells/ml) in rabbits; however, several changes may be associated with an acute infection, including a low total number of white blood cells (<5000 cells/ml) with a normal differential or normal cell counts with a shift to heterophilia, thrombocytopenia, and nucleated red blood cells. Other reasons nucleated red blood cells may be found are endothelial changes and regenerative responses.

Rabbits, like rodents, have control over calcium excretion at the level of the kidney. Elevations in serum calcium can be attributed to an increase in dietary intake of the mineral or to renal disease; a reduction in serum calcium may be indicative of hypoalbuminemia, diarrhea, chronic renal failure, or hyperparathyroidism. Phosphorous can also increase with renal disease, but reduced levels can be seen with calcium excretion in the urine.

As with other mammals, creatinine levels can become elevated when reduced blood flow to the kidney occurs accompanied by a 50% to 70% loss of renal function. Blood urea nitrogen may also rise due to renal disease when 50% to 70% of kidney function is lost. There are a number of potential causes of renal failure in rabbits, including neoplasia, glomerular nephritis, and pyelonephritis. Elevations in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine can also occur with postrenal diseases (e.g., urethral calculi) and prerenal diseases (e.g., dehydration).

There are no liver-specific enzymes in rabbits. In many mammals, alanine aminotransferase is liver specific; however, in rabbits, this enzyme is found in both the liver and cardiac muscles. Aspartate aminotransferase is found in a number of tissues, including muscle (cardiac, skeletal, smooth), liver, kidneys, and pancreas. Elevations of both enzymes, however, should be considered suspicious and other testing done to rule out liver disease (e.g., liver biopsy). (See Table 14-1 for rabbit hematologic and serum chemistry reference ranges.)

TABLE 14-1.

Reference Hematologic and Serum Chemistry Values for Rabbits

| Parameter | Range | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Erythrocytes (×106/μl) | 4.9-7.8 | Anisocytosis, polychromasia, low numbers of NRBCs, and Howell-Jolly bodies can be normal on rabbit blood smears for pet rabbits. |

| Hematocrit (%) | 31-50 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 10-17.4 | |

| MCV (fl) | 57.5-75 | |

| MCH (pg) | 17.1-23.9 | |

| MCHC (%) | 28.2-37 | |

| Platelets (×103/μl) | 250-650 | |

| Leukocytes (×103/μl) | 5.2-12.5 | |

| Heterophils (%) | 20-75 | In healthy rabbits, heterophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is usually 1 : 1 or slightly lymphocytic. |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 30-85 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 2-10 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0-5 | |

| Basophils (%) | 0-8 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 4-16 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 14-80 | |

| AST (U/L) | 14-113 | |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 16.2-38 | |

| Bilirubin, total (mg/dl) | 0-0.75 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 13-30 | |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 5.6-14 | |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 92-112 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 10-80 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.5-2.5 | |

| Glucose (g/dl) | 75-155+ | |

| LDH (U/L) | 43-129 | |

| Lipids, total (mg/dl) | 243-390 | |

| Phosphorous (mg/dl) | 2.3-6.9 | |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.6-6.9 | |

| Protein, total (g/dl) | 5.4-8.3 | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.4-4.6 | |

| Globulin (g/dl) | 1.5-2.8 | |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 131-155 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 124-156 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; NRBCs, nucleated red blood cells.

Combined data from Carpenter JW, Mashima TY, Gentz EJ et al: Caring for rabbits: an overview and formulary, Vet Med Rabbit Symposium: Rabbits Are Not Small Cats, pp 348-380, April 1995; Harcourt-Brown F: Textbook of Rabbit Medicine, London, 2002, Elsevier; Mader DR: Basic approach to veterinary care. In Queensberry KE, Carpenter JW, editors: Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, St Louis, 2004, WB Saunders; Fudge AM: Laboratory Medicine: Avian and Exotic Pets, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders.

The electrolytes reference ranges for rabbits are similar to those described for other mammalian vertebrates (see Table 14-1). Elevations in sodium and chloride can occur with dehydration or excess salts in the diet, whereas losses are generally associated with diarrhea or low dietary salt. Potassium levels may be low in animals with diets low in potassium or in animals that are starved. Total protein levels in rabbits can be higher compared to those levels found in other vertebrates.

Urinalysis

A urinalysis can provide a significant amount of information regarding a rabbit's health. Either a free-catch or cystocentesis urine sample can be used, but the cystocentesis sample is preferred. To perform a cystocentesis in a rabbit, a 22- to 25-gauge needle fastened to a 6-ml syringe is needed. The rabbit should be placed in dorsal recumbency. The bladder can be difficult to palpate; however, with care, it can be found cranial to the pelvis. The cystocentesis site should be disinfected with 70% isopropyl alcohol. The rabbit bladder should be stabilized between the index finger and the thumb, and the needle inserted along the ventral midline into the bladder. The consistency of the urine should be noted.

Urinary catheterization can be performed with a well-lubricated 9-French catheter inserted into the urethra.11 Rabbit urine is generally straw-colored and clear to cloudy. If the urine has a red appearance, then it is important to rule out blood in the urine from porphyrins. To differentiate hematuria from porphyrin pigmentation, use a urine dipstick or a woods lamp, as porphyrins will fluoresce. If a urinary tract infection is suspected, obtain a cystocentesis and submit a culture and sensitivity in addition to performing a complete urinalysis. Cloudy urine in rabbits is usually due to calcium excretion and the presence of crystals. The presence of crystals in the urine can make it difficult to identify bacteria on a cytologic test, and a culture should be performed if a bacterial cystitis is suspected. (See Box 14-2 for normal urinalysis values.)

BOX 14-2. Reference Ranges for a Rabbit Urinalysis.

| Specific gravity | 1.003-1.036 |

| pH | 8.2 |

| Crystals | Calcium carbonate monohydrate, anhydrous calcium carbonate, ammonium magnesium phosphate |

| Casts, cells, bacteria | None |

| WBC | Occasional |

| RBC | Occasional |

| Albumin | In young occasionally |

| Average urine production | 130 ml/kg/day |

From Mader DR: Basic approach to veterinary care. In Queensberry KE, Carpenter JW, editors: Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery, St Louis, 2004, WB Saunders.

Fine needle aspirates can be done to ascertain the histologic response of a mass. Although abscesses are a common finding in dermal and subcutaneous masses, neoplasia, granulomas (e.g., fungal), and hematomas can also occur. Rabbit abscesses are generally inspissated, so it is difficult to obtain much of a sample from a fine needle aspirate. The procedure for fine needle aspiration in a rabbit is similar to the technique described for domestic mammals. Using a local anesthetic can minimize the pain associated with the procedure. Applying topical EMLA cream (AstraZeneca LP, Wilmington, DE) over the fine needle aspirate site 20 to 30 minutes before performing the procedure can minimize the discomfort associated with the procedure.

Bone marrow aspirates should be performed when blood cell production problems are suspected. The proximal femur is the preferred site for sample collection. This procedure should be done with general anesthesia. A standard sterile preparation should be done to minimize the likelihood of introducing opportunistic skin pathogens. A spinal needle with a stylet should be used to perform the procedure. The needle should be inserted in the trochanteric ridge.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography is a useful diagnostic test in rabbit medicine. It is important to always take at least two radiographs (e.g., lateral and dorsoventral/ventrodorsal). Many times radiographs of the abdomen or thorax can be taken with little or no sedation if the handlers are patient and careful. If more restraint is necessary, isoflurane or midazolam can be used to sedate or immobilize the patient. Skull radiographs are required to evaluate the roots of molars and incisors and should be taken in cases of suspected or known malocclusions. The most useful radiographic views for examining the teeth are rostrocaudal, dorsoventral, and lateral (Figure 14-7 ). In cases of ocular discharge, contrast media can be injected into the lacrimal duct to determine if any of the molar roots are impinging on the duct (Figure 14-8 ). Chronic cases of otitis or neurologic disease warrant evaluation of the tympanic bullae for radiographic changes. In cases of facial abscess, radiology can be used as a prognostic indicator; periosteal bone reaction decreases the prognosis for full recovery.

Figure 14-7.

Normal lateral skull radiograph of a domestic rabbit.

Figure 14-8.

Contrast media can be instilled into the nasolacrimal duct to determine if the incisors are impinging on the duct.

Abdominal radiographs can be used to assess the gastrointestinal, reproductive, and excretory systems. Survey radio graphs can be useful for diagnosing ileus or gastric foreign bodies. Rabbits with severe generalized ileus carry a grave prognosis. Rabbits with trichobezoars are frequently anorectic. Therefore, the presence of a soft tissue mass in the stomach of an anorectic rabbit is highly suggestive of the presence of a gastric foreign body (e.g., trichobezoar). In cases where a gastrointestinal foreign body is suspected but not conclusive from survey radiographs, the veterinarian should consider doing a contrast study. Uterine adenocarcinoma should be considered in a differential list for any intact doe with a suspicious soft tissue mass in the caudoventral abdomen. Renal, urethral, and cystic calculi can generally be diagnosed from survey radiographs, although contrast studies are also needed in some cases.

Thoracic radiography is an important diagnostic test for ruling out respiratory and cardiac disease. The thoracic field of a rabbit is small in comparison with that of other mammalian vertebrates (Figure 14-9 ). However, radiograph interpretation is similar. Pneumonia, metastatic neoplasia, and trauma are common disease problems that can be diagnosed radiographically.

Figure 14-9.

Normal thoracic radiograph. Note the small size of the thorax.

In addition to radiography, the other commonly used diagnostic imaging techniques can also be useful for assessing the rabbit patient. Ultrasound can provide excellent images of the abdomen and thorax and has been used to diagnose abdominal pathology, uterine disease, foreign bodies, excretory calculi, and cardiac disease. Success with ultrasound is based on the sonographer having a good knowledge of anatomy, so that he or she can interpret an image based on the position of the probe. A 7.5- to 10-mHz transducer is recommended for rabbit ultrasonography. Clipping the fur of the rabbit in the area of interest can also help improve the image by providing the contact between the skin and the probe; however, caution must be used when clipping the fur, as the skin tears easily. Echocardiography is an appropriate diagnostic aid in cases of suspected heart disease or in patients with audible murmurs. Echocardiographs should be conducted using a high-frequency transducer (7.5-12 MHz) and high frame rate ultrasound machine.4 Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) can prove invaluable in diagnosing certain conditions, including diseases associated with the sinuses, inner ear, cranium, and teeth. Although these tests are becoming more available, they still remain cost prohibitive for some clients.

Microbiology

Bacterial and fungal cultures are routinely collected to assist in the diagnosis of specific pathogens. Interpretation of the results, however, can sometimes require more art than science. It is important for veterinarians to recognize that the results they receive from their laboratories are based on what happens at the level of the culture plate. For example, although Pasteurella multocida is often considered a primary differential in many cases based on the animal's presentation, the culture results may suggest otherwise. P. multocida is a fastidious organism and may be outcompeted on a plate by other organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus spp.). Therefore, the interpretation of the results should be reviewed cautiously.

Rabbits can become bacteremic and develop an infection in practically any tissue. The most common sites of infection, however, are the urinary bladder, respiratory system, and integument. Urine cultures obtained from cystocentesis are preferred to those collected via free-catch. Rabbit urine should have a basic pH. If the urine pH becomes acidic, it will promote the growth of potential opportunistic pathogens. Most pathogens of the urinary tract are Gram-negative bacteria. Female rabbits are more susceptible because of their stouter urethras. In addition to urine cultures, deep nasal cultures for chronic respiratory disease and cultures of abscesses are considered routine. Deep nasal cultures usually require sedation, as the microculturette is advanced into the nasal passage up to the level of the medial canthus of the eye. When culturing an abscess, the best results are often obtained from sampling the abscess wall.11 Samples collected from the nasal sinuses and abscesses often have a significant number of inflammatory cells associated with them. These cells can affect the results of a culture by reducing the number of organisms to the point where analytical sensitivity of culture cannot detect the bacteria. In some cases, serial samples may be needed to determine if an organism is a trace pathogen. Culturing microorganisms from rabbits is otherwise routine. If anaerobes are suspected, then the veterinarian should contact the laboratory to obtain the appropriate media for collection and transport.

Parasitology

Although rabbits are captive bred, and the expectation is that parasites would be absent or low in these animals, parasites remain a problem because few preventive health programs are instituted at the breeding population level. Endoparasites can be diagnosed using routine direct saline smears or fecal flotations. Direct saline smears are preferred for identifying protozoa, whereas a fecal flotation is preferred for finding nematodes, trematodes, and cestodes. Annual parasitological examinations include both techniques. Because parasites can be shed transiently, serial samples should be performed. Pooling fecal samples produced over the course of a week may reduce the likelihood of misclassifying a rabbit's parasitic status. For systemic parasitologic disease, serologic testing or histopathology is required. E. cuniculi, a microsporidian, is generally diagnosed antemortem via serology or postmortem via histopathology. E. cuniculi is shed in the urine and may also be diagnosed from direct visualization in a urine sample, but this is not analytically sensitive. Eimeria steidae, a hepatic coccidian, can be diagnosed antemortem via a fecal direct smear or postmortem via histopathology.

Ectoparasites are also common in captive rabbits. If ectoparasites are suspected, a routine dermatologic examination should be performed, including a skin scrape and mineral oil preparation of the fur. Microscopic examination of these samples can provide confirmation of the presence of these parasites. Multiple samples should be collected to prevent misclassification as negative, and samples should be collected along the edge of the lesion. A flea comb can be used to confirm the presence of adult fleas or flea dirt.

Miscellaneous Diagnostics

SEROLOGY

Serologic testing in rabbits is limited. The two most common serologic tests being used today are for E. cuniculi and P. multocida. As with any test, it is important to know the sensitivity and specificity of the assay to be able to be able to determine the value of the result. The interpretation of a single titer should be done cautiously. If a rabbit has a single positive titer, it suggests that the animal has been exposed to the infectious disease. To confirm that the animal has a current infection, a paired sample would need to be collected 2 to 3 weeks later. A two- to fourfold rise in the titer should be observed before concluding an animal is actively infected. However, in cases where the animal's first titer was already significantly elevated, a similarly high second titer may be used to confirm infection. If the titer is negative, then the animal may not have been exposed to the disease, or the result may have been a false negative. False negative results can occur during a peracute disease when a titer has not developed or when the immunoglobulin being measured (e.g., IgM or IgG) either has not been developed or has already passed. Serologic results should always be interpreted in combination with the animal's physical examination findings.

POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays have improved veterinarians’ ability to diagnose diseases. The PCR test provides a more sensitive method of characterizing the presence of an organism than culture. One shortcoming of PCR is that a specific assay needs to be developed for each disease in a species. If there generally is not a high demand for a test, it will not be developed. PCR tests are available for E. cuniculi and P. multocida.

COMMON DISEASE PRESENTATIONS

Infectious Disease

BACTERIAL DISEASE

Pasteurella multocida

Snuffles is a generic term used to describe upper respiratory tract infection in rabbits. Although a variety of opportunistic pathogens can cause this “disease,” it is generally associated with P. multocida. This is unfortunate because it often leads to misdiagnosis. Snuffles is characterized by purulent nasal discharge, sneezing, and coughing or “snuffling.” Affected animals may be weak, lethargic, and anorectic. Ideally, a deep nasal culture should be performed to determine which species of bacteria is responsible for the infection. Primary dental disease must be ruled out as a differential for purulent nasal discharge.

P. multocida is a Gram-negative organism. This bacterium is relatively fastidious and can be difficult to culture. P. multocida has been associated with multiple clinical diseases, including pneumonia, upper respiratory tract disease, abscesses, pleuritis, pericarditis, pyometra, orchitis, otitis media, neurologic disease, and ocular disease.

Both acute and chronic disease states can occur. In cases of acute pneumonia, animals can succumb within hours, whereas in chronic disease states, there may be limited or no overt clinical signs. Transmission of P. multocida can occur through direct contact with acutely infected animals, fomites, and via airborne bacteria. The pathogen generally is thought to enter the rabbit through the respiratory tract. P. multocida can be isolated from a healthy rabbit's respiratory tract; however, when epithelium and local defenses are disrupted, bacterial numbers can increase to levels at which an infection can occur. Conditions that predispose a patient to P. multocida infections include temperature change, presence of carrier rabbits, poor sanitation (causing increased ammonia fumes), reproduction status, and age.13

A thorough diagnostic work-up should be done because rabbits with other bacteria can exhibit the same clinical signs. Preferably, a diagnosis is made using PCR and paired serology; however, a single serologic sample and positive deep nasal culture may suffice.

A CBC may show an inflammatory leukogram, characterized by heterophils/neutrophils and monocytes, or may be within reference levels. Plasma biochemistry panels are generally within acceptable reference limits; however, if the animal is dehydrated, the panels may show electrolyte and protein disturbances. Radiographs often reveal soft tissue changes in the sinuses and lungs. Ideally, treatment should be based upon culture and antibiotic sensitivity results. Most cases of respiratory P. multocida infections can be treated with enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg PO BID × 14 days), ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg PO SID × 10 days), injectable penicillin (24,000 U/kg SC/IM), or chloramphenicol (50 mg/kg PO BID).4 For chronically infected animals, these treatments need to be extended until the clinical signs are no longer present and the serologic titers decrease. Reproductive disease can be managed by performing an orchiectomy or ovariohysterectomy and providing appropriate antibiotics. P. multocida abscesses can occur anywhere on the body and can be difficult to treat. An extensive review of abscess treatment can be found later in this chapter (see Abscesses).

Bacterial dysbiosis

The microflora of rabbits is comprised of a variety of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. This dynamic flora is what enables the rabbit to thrive on an herbivorous diet. Unfortunately, this microflora is extremely sensitive to several groups of orally administered antibiotics, including clindamycin, lincomycin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cephalosporin, penicillin, and erythromycin.2 These antibiotics can lead to alterations in the microflora, resulting in fluctuations in the intestinal pH, an increase in volatile fatty acids, and proliferation of Clostridium spiriforme. The endotoxemia produced by this organism is responsible for the peracute death of rabbits. If there is no environmental exposure to endotoxin-forming bacteria, this condition will not occur. In general, oral antibiotics are also more likely to cause diarrhea than are parenterally administered antibiotics. Trimethoprim sulfa and enrofloxacin are considered two of the safest oral antibiotics and can be administered orally over extended periods of time. In comparison with oral penicillin, injectable penicillin can be used to treat disease with minimal risk of dysbiosis. Many veterinarians prescribe probiotics to minimize the risk for dysbiosis. Probiotics are comprised of bacteria considered to represent indigenous microflora. These anaerobic microbes are thought to compete for colonization sites within the intestines with pathogens, alter the microflora environment (e.g., pH fluctuations), and produce their own natural “antibiotics” to kill pathogenic bacteria. The true value of these products remains controversial; however, they do not appear to cause disease. Treatment for antibiotic dysbiosis is primarily focused on the provision of supportive care. Fluids should be given to correct losses associated with diarrhea. Calories should be provided to ensure gut motility. Offending antibiotics must be discontinued. Additional safe antibiotics (e.g., enrofloxacin) may be considered to minimize the likelihood of other opportunistic pathogens infecting the compromised epithelium.

Clostridium spp.

Clostridium piliforme, the causative agent of Tyzzer's disease, is a motile, Gram-positive, obligate intracellular bacterium. Infections caused by C. piliforme are commonly reported in compromised rabbits. Overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, inappropriate breeding conditions, and high ambient temperatures have all been associated with C. piliforme outbreaks. Transmission is via the ingestion of spores. Clinical signs shown by rabbits with acute disease can include watery diarrhea, depression, and sudden death. Weanlings (6-12 weeks) are most severely affected; however, this pathogen can cause disease in rabbits of any age. Adult rabbits usually develop a chronic disease course, which can lead to intestinal fibrosis, liver necrosis and stenosis, and myocardial disease.2 Tissue culture and serologic testing are available for diagnosis. Treatment is usually not successful but consists of providing supportive care.

Endotoxemia can be caused by C. spiriforme, C. difficile, and C. perfringes. These organisms can cause significant enteric pathology, and are often associated with a hign number of mortalities. Weanling rabbits are most likely to be affected and may be more predisposed to disease development. Adults can develop clostridial enterotoxemia from inappropriate antibiotic administration, which was described previously.2

Escherichia coli

In neonatal rabbits, colibacillosis is associated with high morbidity and mortality. E. coli is a Gram-negative bacterium from the family Enterobacteriaceae. Members of this family are frequently associated with disease in vertebrates. The most severe disease occurs in rabbits that are 1 to 14 days of age. Affected animals show signs of profuse, watery diarrhea and staining of the abdominal and perineal areas. Dehydration is a common sequela. Intestinal coccidiosis may enhance E. coli proliferation by increasing the severity of the clinical signs.2 A diagnosis can be made from a fecal culture of a pure isolate. A CBC and biochemistry panel should be done, and generally support a diagnosis of an inflammatory disease with dehydration. Treatment should be based on an antibiotic sensitivity profile from the culture. Supportive care, including fluids and calories, is required because of the poor reserves of neonatal rabbits. Generally, the goal of therapy is to quell the spread of disease and prevent additional losses, as clinically affected animals often succumb to the disease.

Miscellaneous bacterial diseases

Lawsonia intracellularis, Salmonella spp., and Pseudomonas spp. are also common pathogens in rabbits. Lawsonia intracellularis is a Gram-negative, spiral-shaped, intracellular bacterium that commonly infects weanling rabbits between 2 and 4 months of age. Affected animals present with profuse, watery diarrhea (e.g., wet tail). Salmonella spp. and Pseudomonas spp. can also cause enteritis in rabbits and are usually disseminated through contaminated food or water sources. Affected animals may present with diarrhea, pyrexia, dehydration, and weight loss. Some animals can become asymptomatic reservoirs. With virulent organisms, peracute death is common. Diagnosis is via culture and antibiotic sensitivity profile. A CBC can provide information regarding the animal's response to the infection, and a radiograph can provide information regarding intestinal motility. Ileus is a common sequela. Treatment should include supportive care and antibiotics.

Treponematosis (Treponema cuniculi), otherwise known as rabbit syphilis, is a sexually transmitted disease that is spread during birth from a doe to a kit. Affected animals often present with crusts on the mucocutaneous junction of the nose, lips, eyelids, and/or external genitalia. Does may abort kits, retain placentas, or develop metritis.14 A diagnosis can be made from a scraping or biopsy. Serologic tests are also available to assist with diagnosis. Silver stain or dark field microscopy is necessary to identify the organisms. Injectable penicillin (40,000 U/kg IM SID × 3-5 days;14 40,000 U/kg IM q7days × 3 treatments)15 is the treatment of choice.

Staphylococcus aureus is considered a component of the indigenous microflora of the nasal cavity, conjunctiva, and skin of rabbits; however, when the epithelial barrier of these structures is compromised, the pathogen can invade. Mammary glands, respiratory and ocular tissues, and the integument are common sites for S. aureus infections. S. aureus infections can lead to fatal septicemia. Diagnosis is based on culture and cytologic and histopathologic testing. Treatment should be based on the antibiotic sensitivity profile. Enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg BID) or trimethoprim sulfa (15 mg/kg BID) are both broad-spectrum antibiotics that can be used to manage the case while the sensitivity profile is pending.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a Gram-negative bacterium that generally infects the upper respiratory tract of rodents and lagomorphs. Infection caused by B. bronchiseptica strikes primarily older animals. Clinical signs include sneezing and nasal discharge; rabbits can also serve as asymptomatic carriers. Culture is used to confirm diagnosis. Antibiotics should be given based on antibiotic sensitivity profile, and, again, enrofloxacin can be used for initially treating the animal.

VIRAL DISEASE

Rotavirus is a disease of neonatal rabbits. Affected animals are generally 4 to 6 weeks of age. In populations where this virus is endemic, there is generally a low morbidity in weanlings; however, if naive animals are exposed to the virus, then the disease course can be severe.16 Rotavirus can cause severe changes to the intestinal villi, including blunting and fusing. Severe damage to the villi can result in inability to absorb nutrients and in loss of fluids.17, 18 There is no effective treatment. Affected animals should be given supportive care and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Quarantine is recommended to prevent introduction of the virus.

Enteric coronavirus causes disease in 3- to 10-week-old rabbits; it is characterized by the loss of the brush border of the enterocytes. Clinical signs in affected rabbits include lethargy, watery diarrhea, and abdominal swelling. Morbidity can reach between 40% and 60%. Death usually occurs within 24 hours of the onset of signs. Corona or corona-like virus can lead to pleural effusion disease or infectious cardiomyopathy. Infected rabbits may present for anorexia, weight loss, tachypnea, or sudden death. Mortality can exceed 75% of affected animals. Virus isolation from the feces and histopathology consistent with the disease are the two common methods of diagnosis. Affected animals should be provided supportive care and broad-spectrum antibiotics to combat opportunistic bacterial infections. This virus can be isolated from healthy adult rabbits. Because of this, quarantine and prescreening animals are recommended to prevent introduction of the virus into rabbitry.

Myxoma virus is a member of the poxvirus family. The virus group has two distinct geographic origins: South America and California. Myxoma virus is associated with a benign cutaneous fibroma in its natural hosts: Sylvilagus bachmani (wild brush rabbits in the western United States—the Californian type), and S. brasiliensis (the South American type). Both of the myxoma strains can cause lethal disease in the European rabbit.3, 16 Although rare, this virus has been found to cause high mortality in domestic rabbits from Oregon and California.19 This virus is transmitted via mosquitoes and fleas. The clinical signs associated with myxomatosis in natural hosts include swelling of the eyelids, face, head and testes/scrotum, the production of a milky ocular discharge, 1-cm mucoid cutaneous nodules, pyrexia, lethargy, depression, and anorexia. Infected domestic rabbits may become lethargic, pyrexic, anorectic, and develop skin hemorrhages and seizures.4 Death usually occurs within 14 days of clinical onset. Although the exact mechanism leading to the animal's demise is not well understood, it has been suggested that it is due to the proliferation of Gram-negative bacteria secondary to the immunosuppression caused by the virus. No effective therapy is known, and euthanasia is recommended.15 Cross-immunity can be achieved using a live, attenuated, Shope fibroma virus vaccine. However, the vaccine does not provide full coverage and is safe only in healthy nonpregnant animals. Boosters should be administered at 6- to 12-month intervals in susceptible animals.15

Shope fibroma virus is a Leporipoxvirus and is related to the myxoma virus. Cross-immunity can be inferred between the viruses. Shope fibroma virus can cause localized, benign fibromas and generalized disease in newborn, wild rabbits. Outbreaks have been reported in rabbitries. Clinical signs include subcutaneous, nonattached, wart-like fibromas on the legs or feet and around the muzzle and eyes. In young rabbits, this virus has been associated with lethargy, reduced body condition, skin lesions, and edema.20 Diagnosis is made from histologic samples. No treatment is available.

Shope papillomavirus is the causative agent in papillomatosis. This disease is generally found in wild cottontails from the midwestern United States. Domestic rabbits are susceptible to the disease, and outbreaks have been reported in rabbitries. Horny warts are the most common clinical finding, and they are generally found on the shoulders, abdomen, and neck. Oral papillomavirus can also lead to the development of papillomas on the ventral surface of the tongue; however, cross-immunity develops when the virus causes dermal lesions. Diagnosis is made based on histopathologic findings and viral isolation. There is no treatment for this virus. The virus can induce malignant neoplasia that is similar to squamous cell carcinoma.

Rabbit pox is a rare but highly contagious disease. Clinical signs include lymphadenopathy, fever, and dermatologic changes (e.g., crusts, nodules, papules). Death can occur in severe cases. Edematous changes may also be seen on the face, oral cavity, scrotum, and vulva. Diagnosis is via viral isolation and histopathology.4 There is no treatment for this virus.

Rabbit calicivirus, formerly known as rabbit viral hemorrhagic disease, is a viral-induced hemorrhagic disease. This virus is primarily found in the eastern hemisphere. An outbreak in Mexico occurred in 1988; however, the virus has since been eradicated from that country. A single outbreak has been reported in the United States; the event occurred in Iowa. Morbidity from this disease can be as high as is 70% to 80%, and mortality can approach 100%. The virus is spread directly from infected to noninfected rabbits. Infected rabbits may present for frank hemorrhage around the face and muzzle, tachypnea, cyanosis, abdominal distension, constipation, or diarrhea.20

FUNGAL DISEASE

The most common fungal infections of rabbits are associated with Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Microsporum canis. Clinical signs in infected rabbits are similar to those reported in infected domestic pets and include crusty erythematous alopecia that may or may not be pruritic. Lesions can occur anywhere on the body but are often found on the head, shoulders, and legs. Ringworm is most often diagnosed in young animals that have received inappropriate husbandry. A diagnosis can be made with a KOH preparation from a skin scrape or fungal culture.21 Infected rabbits can be treated with weekly lime-sulfur dips, a topical povidone-iodine cleansing agent, and, in severe cases, griseofulvin (25 mg/kg PO BID × 30 days).21 Because this disease is potentially zoonotic, clients should be advised to minimize handling during treatment. Rabbits can acquire ringworm from humans too, so clients should be advised to consult their clinician if they are the source of infection.

Parasitic Disease

ENDOPARASITES

Coccidial infections are common when rabbits are held at high densities under inappropriate husbandry conditions. Infections are more problematic in weanling rabbits. Eimeria spp. can infect both the intestinal tract and the liver (E. steidae). The transmission of these protozoal parasites is via the fecal-oral route. Sporulated oocysts represent the infectious stage. Clinical signs associated with intestinal coccidiosis include inappetence, weight loss, dehydration, diarrhea (± hemorrhagic), and, in chronic cases, intussusception. Hepatic coccidiosis is considered a more serious disease. Rabbits infected with hepatic coccidiosis may have limited growth, diarrhea, weight loss, dehydration, ascites, hepatomegaly, icterus, and hepatic encephalopathy. Severe cases can result in death. A fecal flotation and direct smear or histopathology can be useful to confirm a diagnosis. Treatment may be accomplished using trimethoprim sulfadiazine (30 mg/kg PS or SC BID × 7-10 days), sulfadimethoxine (50 mg/kg PO once, then 25 mg/kg SID × 21 days), or sulfaquinoxaline (0.025% in feed or pellets).14 Extended treatments may be required for some populations. If routine treatment is practiced, then the anticoccidial drugs should be rotated to minimize the likelihood of inducing resistance.

E. cuniculi is an obligate, intracellular, microsporidian protozoan.22 The parasite is disseminated via contaminated urine. E. cuniculi is shed transiently and can live for 4 weeks at room temperature. Clinical signs can vary depending upon the organ or system affected and the severity and duration of the disease. This protozoan affects primarily the kidneys, eyes, and neurologic system. Most infected rabbits present for vestibular disease. Clinical signs may include head tilt, hemiparesis, an inability to right itself, tumbling/rolling, seizures, ataxia, and paralysis (Figure 14-10 ). When E. cuniculi affects the neurologic system, the prognosis for recovery is grave. In some cases, rabbits show a reduction in vestibular signs but require life-long treatment. Without treatment, the quality of life is usually poor, and euthanasia is recommended. When the kidneys are affected, clinical signs may be absent because renal function is not usually altered. Cataracts and uveitis are common sequelae to ocular infections (Figure 14-11 ). Phacoemulsification is the treatment of choice for E. cuniculi–induced cataracts. Without treatment, the lens can rupture and induce a phacoelastic uveitis. Diagnosing E. cuniculi antemortem is usually done from the physical examination, hematology, and serology. Serology is generally only used to rule out E. cuniculi infection; however, a positive titer does not conclusively rule in disease. Albendazole, fenbendazole, or oxibendazole is generally used to minimize the inflammatory response associated with the infection.4 Antibiotics that penetrate the blood-brain barrier (e.g., chloramphenicol) can be used to combat opportunistic infections. Diazepam can be used to control seizures. Although some corticosteroids have been used for treating E. cuniculi, they can cause immunosuppression and should be used with caution. The steroid's primary benefit is to increase the uptake of the respective antiparasitics. Life-long treatment is required to minimize the clinical signs associated with the disease.23

Figure 14-10.

Head tilt in rabbit caused by E. cuniculi.

Figure 14-11.

Lenticular changes associated with an E. cuniculi infection.

(Courtesy Dr. David Guzman.)

Baylisascaris procyonis, the raccoon roundworm, has been documented in rabbits and can be associated with fatal neurologic disease. Affected animals may present for torticollis, ataxia, and tremors.24 Rabbits become infected from eating food or drinking water contaminated with raccoon feces. A diagnosis can be made from a serologic titer (exposure) or postmortem. Albendazole can be used to minimize the clinical disease associated with the parasites.

ECTOPARASITES

Cuterebra larvae, or bot flies, are common finding in rabbits housed outdoors. The larvae can be diagnosed easily by the presence of a small breathing hole. Infected rabbits generally have 1 to 5 bot larvae. The animal's fur may be matted around the breathing hole as a result of the rabbit licking in reaction to the pain associated with the larvae. Treatment requires surgical removal of the larvae. An incision should be made through the air hole, and the larvae extracted. The larval cyst should be removed to prevent secondary opportunistic infection. Care should be taken not to crush the larvae during extraction, as this can lead to anaphylaxis. Rabbits housed outdoors should be protected against flies by means of appropriate fly traps and cage screening.

Fly strike, or myiasis, is a common presentation for rabbits housed outdoors during the summer. Obesity, underlying dermatitis, and unsanitary conditions can predispose a rabbit to this condition. Aggressive wound debridement and maggot removal are required to treat affected rabbits. Ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg SC once) can be used to kill the maggots. Antibiotics may be used if the wound is large or there is a concern for systemic disease. Analgesics should be used during wound treatment to control pain. The dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (C. felis) are the most common fleas found on rabbits. The fleas are found primarily along the dorsum between the shoulders and pelvis. Flea powder that is safe for kittens can be used for rabbits. Although not labeled for use in rabbits, lufenuron (Program, Novartis Animal Health Canada, Mississauga, Ontario) and Advantage (Bayer Animal Health, Agriculture Division, Shawnee Mission, KS) for cats have been used safely for rabbits. For rabbits that are 10 weeks of age and less than 4 kg, 0.4 ml of topical solution can be applied to the skin at the base of neck, as recommended for dogs and cats. Rabbits that are ≥4 kg can be treated with 0.8 ml.4 When treating the animal's environment, it is important to remove the rabbit and only return it once the chemicals are dry. Frontline (Merial Limited, Duluth, GA) should not be used on rabbits, as it can cause liver impairment.

Cheyletiella parasitovorax, an obligate, nonburrowing mite, is commonly referred to as “walking dandruff” (Figure 14-12 ). Clinical signs associated with an infection include mild pruritus, large flakes of white scales on limbs and neck, alopecia, and oily dermatitis. Infestations occur more commonly in young, obese, or otherwise immunosuppressed animals. A diagnosis can be confirmed from the microscopic examination of a skin scrape or scotch tape prep. Ivermectin (0.2-0.4 mg/kg SC × 3 treatments) is the treatment of choice.4 Lime-sulfur dips and flea powder can also be used to treat affected rabbits. Cleaning the environment and treating other affected animals are also required to eliminate this parasite. This parasite can be zoonotic, so it is important to advise clients to take precautions when handling/treating affected animals.

Figure 14-12.

Cheyletiella parasitovorax is often described as “walking dandruff.”

Psoroptes cuniculi is the common rabbit ear mite. Affected animals can develop severe otitis externa. The external canal and pinnae can also have significant quantities of crusty exudates. The crusty exudate is the result of a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite and can cause a significant discharge and pruritus. One or both ears can be infested. Ear mites are transmitted by direct contact or contact with fomites. Mites can survive off the host for 21 days. Psoroptes’ life cycle is 21 days. Ivermectin (0.4 mg/kg SC, ½ done in each ear) or selamectin (Revolution; Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY) (6 or 18 mg/kg topically 1-2 times) can be used to eliminate mites.25 Do not remove the crusts or clean the ears, as the skin under the crusts is ulcerated and painful. Prednisone (0.5 mg/kg PO BID × 5 days) or meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg PO BID × 5 days) may be used to reduce the otitis and provide pain relief.

Sarcoptes scabiei, the causative agent of scabies, can induce a crusty, pruritic dermatitis of the face, nose, lips, and external genitalia.2 Diagnosis is via a deep skin scrape of the lesion. Ivermectin (0.4 mg/kg SC q14days × 3 treatments) or weekly lime-sulfur dips (1 : 40) and environmental clean-up can be used to eliminate the mites. The mite is zoonotic, so clients should be instructed to wear gloves when handling/treating an infected animal.

Passalurus ambiguous, a pinworm, is considered by some to be commensal. This nematode is thought to play a role in the digestion of plant material. Clinical disease has been attributed to heavy burdens. Affected animals may be anorectic, lose weight, develop impaction, and be in poor condition. A diagnosis can be made from a fecal flotation. Fenbendazole (20 mg/kg PO SID × 5 days), thiabendazole (50 mg/kg PO q2 wk-q3 wk), or Piperazine (200-500 mg/kg/day PO × 2 days) can be used to treat affected animals.3, 5, 15