Abstract

Objectives:

To test differences in cognitive outcomes among adolescents randomly assigned, as infants, to iron-fortified formula or low-iron formula as part of an iron-deficiency anemia preventive trial.

Study Design:

Infants were recruited from community clinics in low- to middle-income neighborhoods in Santiago, Chile. Entrance criteria included term, singleton infants, birth weight ≥ 3.0 kg, with no major congenital anomalies, perinatal complications, phototherapy, or hospitalization > 5 days, chronic illness, or IDA at 6 months. Six-month-old infants were randomized to iron-fortified (12mg/L) or low-iron (2.3mg/L) formula for six months. At 16 years, cognitive ability, visual perceptual ability, visual memory and achievement in math, vocabulary, and comprehension were assessed, using standardized measures. We compared mean differences in developmental test scores according to randomization group.

Results:

At the follow-up assessment, participants averaged 16.2 years old and 46% were male. Those randomized to iron-fortified formula had lower scores than those randomized to low-iron formula for visual memory, arithmetic achievement, and reading comprehension achievement. For visual motor integration, there was an interaction with baseline infancy hemoglobin, such that the iron-fortified group outperformed the low-iron group when 6-month hemoglobin was low and underperformed when 6-month hemoglobin was high.

Conclusions:

Adolescents, who received iron-fortified formula as infants (from 6 to 12 months) at levels recommended in the US, had poorer cognitive outcomes compared to those who received low-iron formula. Prevention of iron deficiency anemia in infancy is important for brain development. However, the optimal level of infancy iron supplementation is not settled.

Keywords: iron supplementation, cognitive development, infant nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a global public health problem considered to be the “most common and widespread nutritional disorder in the world”.(1) Infancy IDA is associated with negative health outcomes, including poorer cognitive, motor and socio-emotional development.(2, 3) In many countries, it is routine to supplement infant formula and foods with iron in order to prevent IDA.

Despite routine iron fortification of infant formulas, there is limited research assessing the optimal level of iron fortification and long-term effects on the developing brain.(4) Expert organizations worldwide differ on the recommended level. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Nutrition recommends that formula-fed infants receive formula containing 179–214 μmol/L (10 – 12 mg/L) of iron beginning at birth.(5) The European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recommends lower concentrations of iron in infant formula (32.2 – 140.0 μmol/l) (4–7 mg/L),(6) with some countries recommending “follow-on” formulas with higher concentrations of iron after 6 months.

We previously reported lower developmental test scores in 10-year-old children randomized to iron-fortified formula (12 mg/L) in infancy compared to those randomized to low-iron formula (2.3 mg/L). Effects varied by 6-month hemoglobin concentration. Specifically, children with higher 6-month hemoglobin concentrations (>128 g/L) randomized to iron-fortified formula had lower scores compared to those randomized to low-iron formula. Children with lower 6-month hemoglobin concentrations (<105 g/L) who received iron-fortified formula had better performance compared to those supplemented with low-iron formula.(7) The aim of the current study was to assess cognitive outcomes in adolescence comparing youth randomized to iron-fortified formula to those randomized to low-iron formula in infancy, taking into account the role of 6-month hemoglobin status.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

The Santiago Longitudinal Study began as a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) in 1991, designed to evaluate the behavioral and developmental effects of preventing IDA in infancy. Participants were recruited from community clinics in four contiguous working-class neighborhoods on the outskirts of Santiago, Chile. (This study could not have been done in the U.S. in 1991, as use of iron-fortified formula, in the first 6 months, had become almost universal.(8) Infant malnutrition had become uncommon in Chile. However, there was no program of universal infant iron supplementation.) Term, singleton infants, were eligible for the study if delivered vaginally, weighing ≥ 3.0 kg, with no major congenital anomalies, perinatal complications, phototherapy, hospitalization for longer than 5 days, chronic illness.(8) The following exclusion criteria were used: residence outside neighborhoods, another infant <1 year of age in household, illiterate or psychotic caregiver, no stable caregiver, infant in child care, IDA at 6 months or “exclusive” breastfeeding, defined as <250 mL/d cow milk or formula. The rationale for excluding households with more than one infant < 1 year was to ensure that the formula (provided by the study investigators with careful monitoring of volume consumed) was only consumed by the enrolled participant. Enrollment for the randomized controlled trial of iron-fortified formula (12 mg/l) compared to low-iron formula (2.3 mg/l) to prevent IDA occurred between 1991 and 1994. Infants who were already taking at least one bottle of milk or formula per day (≥ 250 ml) were randomly assigned to iron-fortified or low-iron formula from 6–12 months.(8) Infant formula was donated by Abbott-Ross Laboratories. The formula was in powder form and the iron supplement was ferrous sulfate. Identical appearing cans were numbered to identify randomization group. The RCT was double blind; whether the infant was receiving iron-fortified or low-iron formula was not disclosed to the families or project personnel.(7, 9). Continued partial breast feeding was encouraged. At weekly visits from 6 to 12 months, home visitors recorded the volume of formula consumption per day (ml/day).

Fingerstick hemoglobin concentration (HemoCue, Leo Diagnostics, Helsingborg, Sweden) was used to screen for infants with IDA. Infants with a low hemoglobin level (10.3 g/dL) and the next nonanemic infant were assessed by venipuncture. Those with iron-deficiency anemia, confirmed on a venous blood sample, were excluded and treated with iron. Anemia at 6 months of age was defined as a venous hemoglobin level of 10.0 g/dL or less. Iron deficiency was defined as two or more abnormal iron measures (mean corpuscular volume, < 70 µm3; free erythrocyte protoporphyrin, ≤ 100 µg/dL; and serum ferritin < 12 ng/mL). All other infants were randomized to receive the study-provided formula between 6 and 12 months of age; the only measure of iron status available for all infants before randomization was capillary hemoglobin level

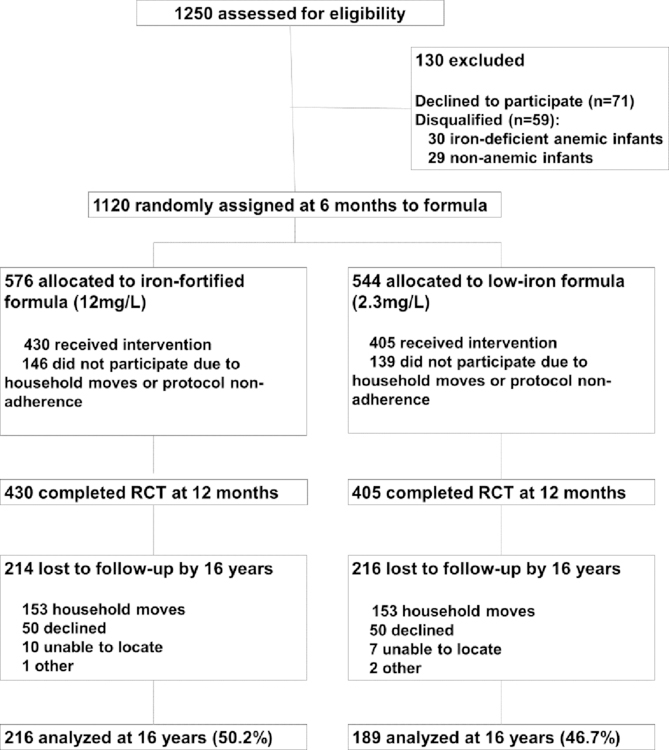

The study was powered to detect 2-point group differences in infancy developmental scores at 12 months. Determination of sample size has been previously described.(8) At 12 months, 835 infants completed the RCT: 430 randomized to iron-fortified formula, and 405 randomized to low-iron formula (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant group differences in attrition, background characteristics, initial hemoglobin concentrations, formula intake, mental and motor scores, or growth before, during, or at the conclusion of the RCT.(7)

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart detailing enrollment, allocation, follow-up and analysis (CONSORT)

At 12 months, infants iron status was determined in venous blood. The criteria for anemia was hemoglobin concentration <11.0 g/dL and for iron deficiency was two or more abnormal iron measures with the same cutoff values as at 6 months.(8) Infants who had ID and anemia were considered to have IDA. At the end of the trial, 19% of infants randomized to iron-fortified formula were iron-deficient, and 2.8% had IDA. Among those randomized to low-iron formula, 35% were iron deficient and 3.8% had IDA. At 18 months, only those randomized to low-iron formula, had venous hemoglobin measured. Infants with IDA at 12 or 18 months were treated with 30 mg/day of oral iron as ferrous sulfate. Venous hemoglobin was reassessed after 6 months of treatment. The article by Walter et al provides a full description of the RCT of high- vs low-iron formula. (10)

At 16 years, 405 of those who completed the infancy RCT (iron-fortified vs. low-iron formula) were reassessed with a psychoeducational test battery and a panel of iron measures. These adolescents form the core analytic sample for the current analyses: 216 had received iron-fortified formula and 189 had received low-iron formula. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and assent from the children. The follow-up study was approved by the relevant university Institutional Review Boards at the Institute for Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) - University of Chile, the University of Michigan and the University of California, San Diego.

Outcome Measure

Outcomes at adolescence included a range of visual-motor, achievement, memory and cognitive functioning tests administered by study psychologists. All measures were administered in Spanish. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV) assesses cognitive ability. (10, 11) For the current study, we administered two subtests of the WISC-IV: Matrix Reasoning and Verbal Similarities.(11) For the Matrix Reasoning test, the adolescents were shown visual patterns with something missing and asked to select the missing piece from five available options, testing visual processing and spatial perception. For the Verbal Similarities test, the adolescents were presented with two objects or concepts and asked to explain how they were alike or dissimilar (i.e., milk-water, butterfly-bee), testing logical thinking and verbal abstract reasoning. The raw scores for each test were standardized to mean (standard deviation (sd)) of 10 (3), as recommended in the WISC-IV manual. The range of standardized WISC-VS and WISC-MR scores was 0–19.(11)

The Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test, a commonly used neuropsychological test, measured visual perceptual ability and visual memory.(12) In this task, the adolescents were asked to copy a complex, two-dimensional geometric figure containing 18 specific elements, while looking at the diagram (visual perceptual ability) and then again from memory, 3 minutes after the stimulus and copy were removed (visual memory).(12) The test was scored on the adolescent’s ability to reproduce each element (0.5–2.0, total score 0–36).(13)

The Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised (WRAT-R) is a measure of academic achievement. (14) We administered the math computation (arithmetic achievement) from the WRAT. In addition, standardized tests for Spanish word reading (vocabulary achievement), and sentence comprehension (reading comprehension achievement) tasks were completed.(15) All three tests were scored based on the number of correct responses. Raw scores were standardized to mean (sd) of 100.

Participants also completed the Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration (VMI) and supplemental test of motor coordination.(16) In the VMI core task, participants were required to copy a series of increasingly complex geometric figures, assessing coordination between hand movements and visual perception. In the VMI supplemental test of motor coordination, participants were instructed to trace geometric forms with a pencil. Both tests were scored based on accuracy and standardized to mean (sd) of 100 (15) in accordance with the test manuals.

Covariates

The following background factors, assessed in the infancy study, were potentially associated with study outcomes and included as covariates: sex, birthweight socioeconomic status, mother’s IQ, infant’s home environment, growth between 1 and 6 months, and infant feeding including ml/day of infant formula. The modified Graffar, used to assess family socioeconomic status (SES) in infancy,(17) consists of 13 indices assessing living and housing conditions, material possessions, etc., each with a score from 1 to 6, with 6 indicating lower SES. Maternal IQ was assessed with an abbreviated Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) when the child was seven months old.(18) WAIS scores were standardized so that the mean was 100.(18) The home environment in infancy (organization of physical environment, stimulation of infant, mother’s emotional and verbal responsiveness, etc.) was measured at 9 months with the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) inventory.(19) At 11 months, mothers responded to a 30-item checklist of stressors (e.g. death of a family member) on a modified Social Readjustment Rating Scale.(20) We also considered adolescent age of assessment.

Missing values for covariates were imputed using all available infancy data following the sequential imputation technique with IVEWARE software, including approximately 0.1% of gestational age data, 30% of maternal IQ data, 36.4% of HOME data, and 17% of SES data.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 statistical software. Univariate and bivariate analyses were used to describe the means and frequencies of participant characteristics in the full sample and in each randomization group. Unadjusted means (sd) of each cognitive test, by supplementation group, are reported. Group differences at 16 years were tested for each outcome using multivariable generalized linear models (GLMs). We report mean differences (and 95% confidence intervals) of each cognitive test adjusted for birth sex, maternal IQ, HOME score, gestational age, birthweight, average formula consumption per day (mL/d), infancy SES, and age at assessment (months). In order to test whether or not the associations between supplementation group and cognitive outcomes varied by 6-month hemoglobin status, we introduced a hemoglobin*group interaction term into each GLM model.

We performed an ancillary analysis to account for the fact that, by design, a subset of infants, those with IDA at 12 or 18 months and the next nonanemic healthy infant had been treated with oral iron therapy(n= 47; 20 IDA and 27 non-anemic controls).(21) This treatment could have altered the outcomes and modified the effects of randomization. In order to assess any bias induced by including these infants, we re-ran all analyses excluding them. As the results did not change, these infants were included.

RESULTS

Sample

At 16 years, outcomes were assessed in 49% (n=405) of the infancy sample. There was no significant difference in attrition by randomization group (X2 = 1.06, p = 0.30). Infancy background characteristics (i.e. age, sex, SES, HOME environment, formula intake, and maternal age, IQ and education) were similar in those assessed at 16 years, compared to those not assessed. There were no statistically significant group differences in 16-year hematologic or iron status measures. The adolescent sample differed from the infancy sample in the proportion of males assessed (46% vs. 53% in infancy, X2 = 4.86, p <0.05). Furthermore, maternal IQ was slightly higher in those assessed compared to those not assessed (mean IQ = 84.5 (0.5) vs. 83.1 (0.5), p = 0.04). (Table 1). Sex and maternal IQ were controlled for in all analyses.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics According to Randomization Group

| Characteristic | N | Iron-Fortified (N=216) | Low-Iron (N=189) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy | |||

| Male sex, % | 405 | (99, 45.8%) | (89, 47.1%) |

| Gestational age, wk | 404 | 39.4 (1.1) | 39.4 (1.1) |

| Birth weight, g | 404 | 3504.1 (352.6) | 3504.2 (362.1) |

| Hemoglobin at 6mo, g/L | 405 | 115.5 (8.0) | 116.1 (7.0) |

| Hemoglobin at 12mo, g/L | 405 | 124.6 (8.6) | 123.1 (8.5) |

| Age at first bottle, m | 393 | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.9) |

| Formula intake, ml/day | 405 | 528.0 (164.0) | 541.5 (155.4) |

| Maternal education a, y | 404 | 9.3 (2.8) | 9.3 (2.9) |

| Primary school or less, % | 280 | (153, 70.8%) | (127, 67.6%) |

| High school (9–12), % | 79 | (41, 19.0%) | (38, 20.2%) |

| Some higher education, % | 45 | (22, 10.2%) | (23, 12.2%) |

| Paternal education a, y | 403 | 9.7 (3.0) | 9.7 (3.0) |

| Primary school or less, % | 252 | (141, 65.3%) | (111, 59.4%) |

| High school (9–12), % | 113 | (55, 25.5%) | (58, 31.0%) |

| Some higher education, % | 38 | (20, 9.3%) | (18, 9.6%) |

| Father present | 400 | (179, 83.6%) | (154, 82.8%) |

| Maternal age at birth, y | 398 | 25.6 (5.5) | 26.8 (6.2) |

| Maternal parity | 404 | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Maternal IQ b | 401 | 84.4 (9.5) | 84.6 (10.7) |

| Maternal depression c | 394 | 16.5 (11.4) | 16.4 (12.0) |

| Socioeconomic Status d | 402 | 27.7 (6.3) | 28.4 (6.6) |

| Life stress e | 389 | 4.9 (2.5) | 4.9 (2.7) |

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment f | 402 | 30.2 (4.8) | 30.4 (4.7) |

| Adolescence | |||

| Age at assessment, y | 405 | 16.2 (0.2) | 16.2 (0.3) |

| Education (10–11 grade) | 380 | (156, 78.3%) | (132, 77.1%) |

| Hematocrit, % | 384 | 40.9 (3.8) | 41.2 (3.7) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 384 | 141.8 (13.8) | 142.3 (12.7) |

| Mean cell volume, fl | 384 | 85.2 (4.0) | 85.3 (3.9) |

| Protoporphyrin, ug/dlGR | 384 | 63.5 (12.8) | 65.2 (14.3) |

| Ferritin, ug/L | 383 | 28.2 (16.2) | 25.8 (15.1) |

Values are (N, %) for categorical values and mean (sd) for continuous variable

Between 1965 – 2003, education in Chile was compulsory from ages 6 to 13. In 2003, school became mandatory to 18 years old.

Maternal IQ evaluated by using the WAIS (18)

Maternal Depression evaluated by using the CESD(28)

Social class index evaluated by using Graffar (17)

Life stress evaluated by using the social readjustment rating scale(20)

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment(19)

Cognitive outcomes in iron-fortified vs low-iron groups

The mean age at assessment of cognitive outcomes was 16.2 years (sd = 0.3). The mean grade level was 10. 2 with most (78%) in 10th (42%) or 11th grade (36%) and 17% in 9th grade. A few participants were in middle school (3%), and a few were in 12th grade (2%). Table 2 shows the adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals for each cognitive outcome by supplementation group. Of the nine tests administered, eight showed lower scores in the iron-fortified vs. the low-iron group, three of which were statistically significant (Rey-Osterrieth visual memory, WRAT-R arithmetic achievement, reading comprehension achievement), adjusting for background characteristics. Statistical significance on the WISC Verbal Similarities test was reached when the analysis was rerun, excluding those who received oral iron therapy at 12 or 18 months (n=47). No other findings changed (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mean 16-Year Developmental Test Scores By Randomization Group, Santiago Preventive Trial

| Outcome | N | Meana | Adjusted difference b | P-Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron-Fortified | Low-Iron | (95%CI) | |||

| IQ, Matrix Reasoning | 403 | 7.4 (2.3) | 7.2 (2.4) | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.6) | 0.47 |

| IQ, Verbal Similarities | 403 | 7.9 (2.1) | 8.2 (2.1) | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.1) | 0.12 |

| Spatial, Rey Copy | 275 c | 32.8 (4.1) | 33.4 (2.9) | −0.6 (−1.5, 0.2) | 0.16 |

| Spatial, Rey Memory | 275 c | 22.4 (6.1) | 24.0 (5.8) | −1.7 (−3.2, −0.3) | 0.02 |

| Arithmetic Achievement, WRAT | 403 | 82.3 (10.6) | 84.2 (11.7) | −2.4 (−4.5, −0.3) | 0.02 |

| Reading Achievement, Vocabulary | 384 | 21.5 (7.4) | 22.0 (7.3) | −0.9 (−2.3, 0.5) | 0.22 |

| Reading Achievement, Comprehension | 390 | 11.1 (4.5) | 12.0 (4.7) | −1.1 (−2.0, −0.2) | 0.02 |

| Visual Motor Integration, VMI | 401 | 85.0 (11.8) | 86.7 (9.9) | −1.7 (−3.8, 0.4) | 0.12 |

| Motor coordination, VMI supplemental | 401 | 88.9 (10.1) | 89.3 (10.2) | −0.3 (−2.3, 1.7) | 0.78 |

CI = confidence interval

Unadjusted mean (sd)

Test of difference in means adjusting for birthweight, gestational age, sex, maternal IQ, HOME environment, SES, average ml/day of formula intake, and age of assessment

Administration of Rey tasks was stopped approximately halfway through follow-up to reduce testing burden on participant.

Table 3.

Ancillary Analysis. Mean 16-Year Developmental Test Scores By Randomization Group Excluding Participants Who Received Iron Therapy at 12 or 18 Months

| Outcome | N | Mean (sd)a | Adjusted difference b | P-Value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron-Fortified | Low-Iron | (95%CI) | |||

| IQ, Matrix Reasoning | 355 | 7.5 (2.3) | 7.1 (2.3) | 0.33 (−0.2, 0.8) | 0.19 |

| IQ, Verbal Similarities | 355 | 7.9 (2.2) | 8.3 (2.1) | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.01) | 0.04 |

| Spatial, Rey Copy | 240 b | 32.8 (4.0) | 33.5 (2.5) | −0.8 (−1.7, 0.1) | 0.09 |

| Spatial, Rey Memory | 240 b | 22.2 (6.2) | 23.7 (5.6) | −1.7 (−3.2, −0.1) | 0.03 |

| Arithmetic Achievement, WRAT | 355 | 82.0 (10.4) | 84.7 (11.5) | −3.0 (−5.2, −0.8) | <0.01 |

| Reading Achievement, Vocabulary | 337 | 21.4 (7.4) | 22.0 (7.1) | −0.9 (−2.5, 0.6) | 0.15 |

| Reading Achievement, Comprehension | 342 | 10.9 (4.5) | 12.2 (4.6) | −1.4 (−2.3, −0.4) | <0.01 |

| Visual Motor Integration, VMI | 353 | 84.8 (11.8) | 86.8 (10.1) | −2.0 (−4.3, 0.3) | 0.08 |

| Motor coordination, VMI supplemental | 353 | 88.9 (9.8) | 89.8 (9.8) | −0.8 (−2.9, 1.2) | 0.42 |

CI = confidence interval

Unadjusted mean (sd)

Test of difference in means adjusting for birthweight, gestational age, sex, maternal IQ, HOME environment, SES, average ml/day of formula intake, and age of assessment

Administration of Rey tasks was stopped approximately halfway through follow-up to reduce testing burden on participant.

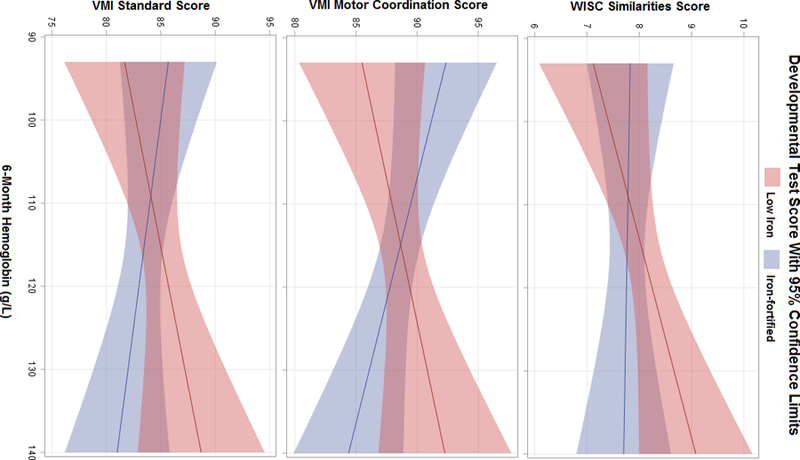

There was a statistically significant interaction between 6-month hemoglobin and randomization group for VMI Motor coordination (p-value = 0.02) and a trend for VMI (p-value = 0.09). For these outcomes, the iron-fortified group outperformed the low-iron group when 6-month hemoglobin was low. However, the iron-fortified group had lower cognitive scores than the low-iron group when 6-month hemoglobin was high (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Adolescents who were randomized to iron-fortified formula (12 mg/L) between 6 and 12 months had lower cognitive scores, at 16 years, compared to those who had received low-iron formula (2.3 mg/L). The low-iron group performed better than the iron-fortified group on eight out of nine measures, with statistically significant differences in verbal comprehension, arithmetic achievement, and spatial memory. Moreover, there was no impact on these findings when infants who became IDA or were treated with oral iron therapy were excluded from the analyses. Similar to findings at 10 years, we found an interaction between 6-month hemoglobin status and iron supplementation at 16 years, but only for VMI. Participants who had low 6-month hemoglobin had higher scores for VMI if they had been randomized to iron-fortified formula and those who had high 6-month hemoglobin had higher scores for VMI if they had been randomized to low-iron formula

We know of no other study comparing iron-fortified formula to low-iron formula in humans. Therefore, ours may be the only study that is able to demonstrate potential adverse outcomes associated with higher-level iron-fortified formula. Based largely on experimentation in animal models, there is increasing concern about the possibility of iron neurotoxicity in the growing infant.(22–25) There are also questions about the effects of iron exposure in early life on brain aging and neurodegenerative disease outcomes.(27) Due to the paucity of research assessing long-term effects of high- vs. low-iron supplementation in healthy infants, our results require replication.

It is important to emphasize that our finding of lower cognitive scores among children and adolescents who received iron-fortified formula in infancy compared to those who received low-iron formula does not negate the use of iron supplementation to prevent infancy ID and IDA.(26, 27) In the same cohort, at the 10-year assessment, we found that participants who received any level of iron supplementation performed better on neurocognitive and socioemotional measures those who did not receive supplementation.(28) Reducing the prevalence of infancy ID and IDA, and the associated health burdens, is a public health triumph. Yet, our results suggest that the ideal level of fortification, for preventing long-term consequences of infancy IDA, may be lower than that found in iron-fortified formula. This period of brain development should be considered as a sensitive period related to exposure to iron. Our findings may lead to further study to determine the optimal amount of iron for supplementation. Another consideration may be individualizing infant iron supplementation based on baseline hemoglobin or iron measures.(4) However, this approach would introduce considerable complexity into public health policy and clinical practice.

This study has several limitations. Infants were enrolled at 4 – 6 months. Therefore, we do not have data on prenatal or neonatal iron status. Eligibility required normal iron status at 6 months. We screened 6-month-old infants by finger prick Hb followed by a venipuncture for any infant with a low Hb. Assessment of iron status may have been more precise if we had used a full panel of iron measures for all infants. In addition, capillary hemoglobin levels are not as accurate as venous measurement and may systematically bias hemoglobin measurement.(29) Thus, our study potentially included infants who would have been excluded had we used venous measurements at 6 months. However, it is unlikely that this misclassification affected validity of the study findings, as it is unrelated to randomization. Additionally, we did not measure iron absorption, thus we were unable to quantify the exact amount of iron metabolically available by supplementation group. Another limitation was that in-depth assessments of some family background characteristics, maternal IQ, depression, life stress, and stimulation in the home (HOME), were only available for ~1000 infants. This was due to budgetary restraints. Participants, assessed for these characteristics, did not differ from those not assessed in other background characteristics. The study is also limited by attrition (25% between 6 and 12 months of age, 43% between 12 months and 10 years, 14% between 10 and 16 of age). There was no differential attrition related to formula group and only minor differences comparing those lost to follow-up to those assessed. Randomization to iron-fortified and low-iron formulas make it unlikely that the adverse effects associated with iron-fortified formulas are attributable to extraneous factors, but differences in unmeasured characteristics are always of concern. The study was conducted in Santiago, Chile; findings may not be generalizable to other contexts.

Strengths of this study include the randomized, longitudinal design and relatively large sample size. Furthermore, the strict eligibility criteria requiring healthy, full-term births reduces the likelihood of confounding by prenatal factors. Additionally, we used a variety of outcome assessments measuring a broad range of developmental domains, such as IQ, motor coordination, visual motor perception, verbal reasoning, spatial perception, and academic achievement. Further research is needed to understand possible mechanisms by which higher levels of iron fortification may contribute to worse developmental outcomes.

In summary, although infant iron supplementation and use of iron-fortified formula has been routine for decades in the U.S. and many other countries, there is limited research assessing optimal levels of iron to prevent infancy IDA and possible adverse effects on the developing brain. This study indicates poorer cognitive outcomes among adolescents who, as infants, received iron-fortified formula at levels recommended in the United States, compared to those who received a low-iron formula. Results from this study may stimulate future research to improve understanding of the complex mechanisms by which iron affects brain development and human health. Our results also support current reassessments of the optimal level of iron fortification/supplementation in infancy, including serious public health considerations related to the possibility of using lower levels of iron supplementation in infancy, a critical period for brain development.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Mean Developmental Test Scores By 6-Month Hemoglobin Level and Randomization Group

Figure displays predicted means by iron supplementation group. Models adjust for birthweight, gestational age, sex, maternal IQ, HOME environment, SES, formula intake (mL/day), and age of assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the participants and their families for making this study possible.

Funding Source: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01 HD033487-15). The work of Erin Delker was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant 5T32-HL-079891-12.

Abbreviations:

- ID

iron deficiency

- IDA

iron deficiency anemia

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- WRAT-R

Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised

- WISC-IV

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures Statement: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the article to disclose

Clinical Trial Registration: The Anemia Control Program: High or Low Iron Supplementation, NCT01166451, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01166451?term=NCT01166451&rank=1

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Daily iron supplementation in infants and children. Daily iron supplementation in infants and children In: Organization WH, editor. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgieff MK. Long-term brain and behavioral consequences of early iron deficiency. Nutrition reviews. 2011;69:S43–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozoff B. Iron deficiency and child development. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2007;28:S560–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hare DJ, Arora M, Jenkins NL, Finkelstein DI, Doble PA, Bush AI. Is early-life iron exposure critical in neurodegeneration? Nature Reviews Neurology. 2015;11:536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker RD, Greer FR, Committee on Nutrition American Academy of P. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126:1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domellöf M, Braegger C, Campoy C, Colomb V, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, et al. Iron requirements of infants and toddlers. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;58:119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lozoff B, Castillo M, Clark KM, Smith JB. Iron-fortified vs low-iron infant formula: developmental outcome at 10 years. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2012;166:208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozoff B, De Andraca I, Castillo M, Smith JB, Walter T, Pino P. Behavioral and developmental effects of preventing iron-deficiency anemia in healthy full-term infants. Pediatrics. 2003;112:846–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter T, Pino P, Pizarro F, Lozoff B. Prevention of iron-deficiency anemia: comparison of high-and low-iron formulas in term healthy infants after six months of life. The Journal of pediatrics. 1998;132:635–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan DP, Kaufman AS. Essentials of WISC-IV assessment: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler intelligence scale for children, revised: Psychological Corporation; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rey A. ‘Psychological examination of traumatic encephalopathy’by A. Rey and’The Complex Figure Test’by PA Osterrieth. Clin Neuropsychol. 1993;7:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neurological tests. Oxford University Press, Inc, New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jastak S, Wilkinson GS. The wide range achievement test-revised: administration manual: Jastak Assessment Systems; 1984.

- 15.Boghani S, Mei Z, Perry GS, Brittenham GM, Cogswell ME. Accuracy of Capillary Hemoglobin Measurements for the Detection of Anemia among U.S. Low-Income Toddlers and Pregnant Women. Nutrients. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beery KE, Buktenica NA, Beery NA. The Beery-Buktenica developmental test of visual-motor integration: VMI, with supplemental developmental tests of visual perception and motor coordination: administration, scoring and teaching manual: Modern Curriculum Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graffar M. Une méthode de classification sociale d’échantillons de population. Courrier. 1956;6:455–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larrabee GJ, Kane RL, Schuck JR. Factor analysis of the WAIS and Wechsler Memory Scale: An analysis of the construct validity of the Wechsler Memory Scale. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1983;5:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley RH, Mundfrom DJ, Whiteside L, Casey PH, Barrett K. A factor analytic study of the infant-toddler and early childhood versions of the HOME Inventory administered to white, black, and Hispanic american parents of children born preterm. Child Dev. 1994;65:880–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1967;11:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Algarin C, Peirano P, Garrido M, Pizarro F, Lozoff B. Iron deficiency anemia in infancy: long-lasting effects on auditory and visual system functioning. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur D, Peng J, Chinta SJ, Rajagopalan S, Di Monte DA, Cherny RA, et al. Increased murine neonatal iron intake results in Parkinson-like neurodegeneration with age. Neurobiology of aging. 2007;28:907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobotka T, Whittaker P, Sobotka J, Brodie R, Wander D, Robl M, et al. Neurobehavioral dysfunctions associated with dietary iron overload. Physiology & behavior. 1996;59:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fredriksson A, Schröder N, Eriksson P, Izquierdo I, Archer T. Neonatal iron exposure induces neurobehavioural dysfunctions in adult mice. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1999;159:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berggren KL, Lu Z, Fox JA, Dudenhoeffer M, Agrawal S, Fox JH. Neonatal Iron Supplementation Induces Striatal Atrophy in Female YAC128 Huntington’s Disease Mice. Journal of Huntington’s disease. 2016;5:53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCann JC, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relation between iron deficiency during development and deficits in cognitive or behavioral function. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;85:931–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozoff B. Early iron deficiency has brain and behavior effects consistent with dopaminergic dysfunction. The Journal of nutrition. 2011;141:740S–6S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozoff B, Castillo M, Clark KM, Smith JB, Sturza J. Iron supplementation in infancy contributes to more adaptive behavior at 10 years of age. The Journal of Nutrition. 2014; 144(6):838–45.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boghani S, Mei Z, Perry GS, Brittenham GM, Cogswell ME. Accuracy of Capillary Hemoglobin Measurements for the Detection of Anemia among U.S. Low-Income Toddlers and Pregnant Women. Nutrients. 2017;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]