Summary

Siderophores are small molecule metal chelators secreted in sparse quantities by their native microbial hosts but can be engineered for enhanced production from heterologous hosts like Escherichia coli. These molecules have been proved to be capable of binding heavy metals of commercial and/or environmental interest. In this work, we incorporated, as needed, the appropriate pathways required to produce several siderophores (anguibactin, vibriobactin, bacillibactin, pyoverdine, and enterobactin) into the base E. coli K-12 MG1655 metabolic network model to computationally predict, via flux balance analysis methodologies, gene knockout targets, gene over-expression targets, and media modifications capable of improving siderophore reaction flux. E. coli metabolism proved supportive for the underlying production mechanisms of various siderophores. Within such a framework, the gene deletion and over-expression targets identified, coupled with complementary insights from medium optimization predictions, portend experimental implementation to both enable and improve heterologous siderophore production. Successful production of siderophores would then spur novel metal-binding applications.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Metabolic Engineering, Biotechnology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Metabolic modeling for siderophore heterologous production through E. coli

-

•

Gene deletion and over-expression targets for five siderophore compounds

-

•

Flux balance analysis and Plackett-Burman combination for media optimization

-

•

Predicted improvements for latter implementation and siderophore application

Biological Sciences; Metabolic Engineering; Biotechnology

Introduction

Siderophores are compounds produced by microbial cells under metal-deficient conditions to sequester metals essential for survival (Miethke and Marahiel, 2007). The metabolic need for siderophores is compounded by the low solubility of metal ions like Fe3+ ions and their scarce availability due to innate anatomical binding mechanisms (i.e., heme chelation). Iron accumulation in common minerals as oxides and hydroxides further complicates ready utilization by microorganisms (Kraemer, 2004). Siderophores are often used as a virulence factor by bacteria to outcompete the host's “nutritional immunity” for iron acquisition. For example, transferrin and ferroportin are used to energize iron transport in mammals (Anderson and Vulpe, 2009), and only those bacteria capable of biosynthesizing siderophores that outcompete these mechanisms can establish residence. As such, the strong binding constants of siderophores to heavy metals like iron have been the result of evolutionary pressure.

Given the binding capacity for metal species, there exist several alternative applications for siderophores. Metals in wastewater released into the environment from electroplating, metal finishing, and other heavy manufacturing processes can build to toxic levels within many life forms. A common removal technique is to increase the alkalinity to induce metal precipitation (Kurniawan et al., 2006). This method fails to completely remove trace amounts of metals. Siderophores, due to extremely strong binding abilities (Raymond and Carrano, 1979), can potentially clear water of such toxic metals. Siderophores can also be used as conjugates for stealth antibiotic transport across target microbial pathogen membranes (Ghosh et al., 2017, Schalk, 2018, de Carvalho and Fernandes, 2014), thus potentially circumventing natural bacterial ability to resist antibiotic entry through cell membrane barriers. Apart from this, siderophores may prompt protective immune responses in plants (Aznar et al., 2014) because exposure creates a metal-deficient environment similar to a bacterial attack.

With such diverse and useful applications, siderophores have tremendous impact potential if produced in significant quantities. However, they are only made in trace amounts from their respective native cellular host systems. As a result, heterologous biosynthesis of such metabolites in surrogate cellular systems like Escherichia coli and yeast have gained attention (Pfeifer et al., 2003, Zhang et al., 2011). Within these alternative hosts, there are different, and generally more amenable, ways to improve cellular-based metabolite production that include (1) random and targeted mutagenesis and screening for higher production mutants, (2) media optimization, and (3) metabolic engineering to address intracellular biosynthetic bottlenecks (Demain, 2006). The first method when conducted at random is experimentally tedious and resource intensive. The remaining methods all benefit from the extended knowledge and advanced engineering tools available to establish heterologous hosts systems, including a range of computational models to better guide product improvement strategies (Orth et al., 2011, Alper et al., 2005).

Many approaches have been developed to model microbial metabolism (King et al., 2015, De Jong et al., 2017). Metabolic networks developed from these models are based on a pseudo-steady-state assumption for ease in calculations (Maarleveld et al., 2013). Such networks are typically underdetermined causing a need for an optimization strategy that is generally linear in nature (Orth et al., 2010). The objective function often chosen to enable a solution for the undetermined network is the flux of the biomass reaction, although this is not the primary target reaction needed to improve product yield (Feist and Palsson, 2010). Flux balance analysis (FBA) is a genome-scale metabolic engineering tool that first establishes and then allows a constrained variation of the carbon flow in a microorganism model based upon steady-state flux distributions with linear flux variations. One issue with FBA is that experimental growth rates resulting from FBA-based perturbations often do not match predictions during early rounds of culturing. A computational solution to this issue was provided through the Minimization of Metabolic Adjustments (MoMA) algorithm in conjunction with FBA (Segre et al., 2002). MoMA additionally accounts for minimum perturbations in flux distributions from the wild-type strain (as a result of genetic changes, for example) and hence reflects the immediate perturbation in output. FBA has also been used in conjunction with other metabolic engineering algorithms to improve product yields. For example, OptForce used with FBA has shown an increased carbon flux toward malonyl-CoA and increased flavanone production by 560% (Xu et al., 2011). Media optimization using the connection between internal metabolic fluxes and external exchange of media components is also an added feature of FBA (Bonarius et al., 1996). Algorithms like OptKnock, Bag of Features, and Genetic Design through Local Search, along with the above-mentioned OptForce, have all been developed to increase the number and precision of gene targets for biosynthetic yield improvement (Burgard et al., 2003, Ranganathan et al., 2010, Lun et al., 2009).

In this work, FBA and its variations have been applied to five siderophore natural products for both media optimization and gene target identification. The structure of the siderophores and their precursors are presented in Figure 1. The results from modeling present the first steps toward a more efficient production system for these siderophores. Subsequent engineering efforts would then be designed to heterologously produce the siderophore compounds and utilize their metal-binding capabilities for a variety of applications.

Figure 1.

Structure of Siderophores and Their Precursors

Results and Discussion

Single Gene Deletions

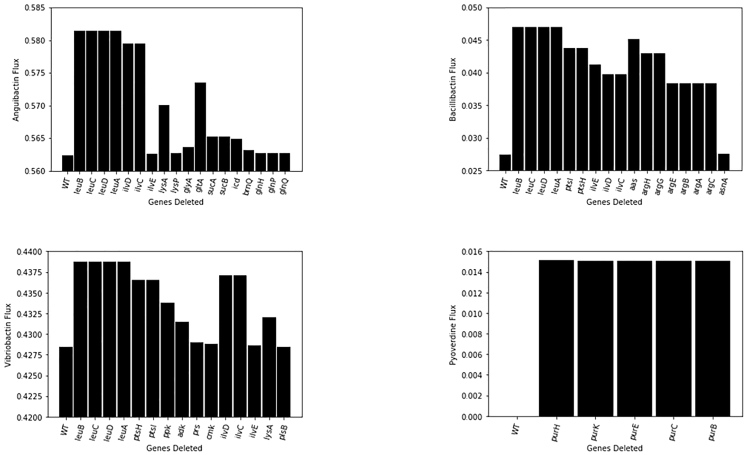

We utilized MoMA to identify gene deletion targets for each siderophore. Our objective function contained fluxes of both biomass and siderophore production. To have significant titers (based in part on commensurate biomass accumulation), we restricted our gene deletion targets to only those that have a steady-state growth rate >0.15/h. Our new product fluxes are selected at the exponential growth phase for comparison with the wild-type strain. We categorize the gene targets identified as non-essential or essential genes (or, alternatively, deletions that would lead to auxotrophy), and the top 25 gene deletions for each siderophore were analyzed for increased product formation (Figure 2), although no unique gene deletions were identified for enterobactin. To aid in the visualization of key gene deletion (and over-expression) targets, heterologous siderophore biosynthesis within the context of E. coli metabolism is illustrated in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 2.

Gene Deletion Targets for Anguibactin, Bacillibactin, Pyoverdine, and Vibriobactin

No gene deletion targets were identified for enterobactin. Flux values are in mmol/gDCW/h and represent compound flux after gene deletion.

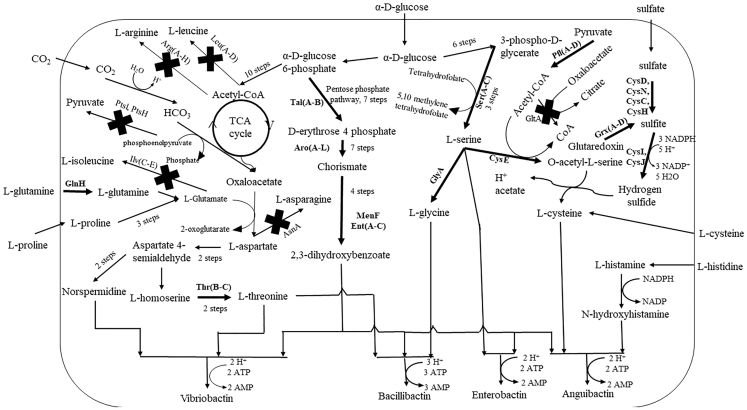

Figure 3.

Anguibactin, Bacillibactin, Vibriobactin, and Enterobactin Biosyntheses

Selected gene deletions and over-expressions have been indicated with an X and a thickened arrow, respectively.

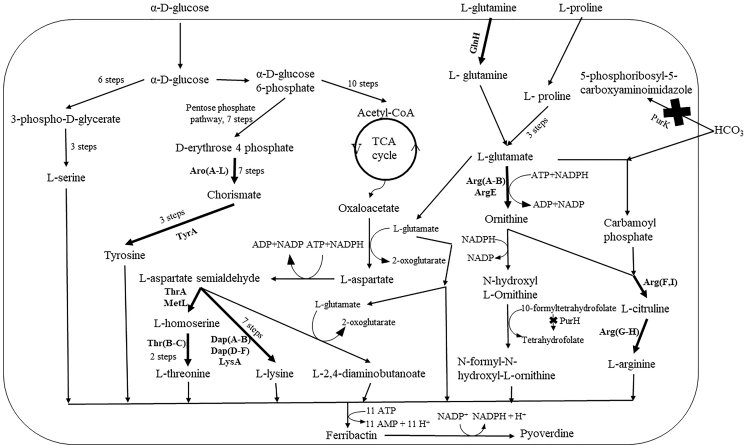

Figure 4.

Pyoverdine Biosynthesis

Selected gene deletions and over-expressions have been indicated with an X and a thickened arrow, respectively.

For anguibactin production, deletion of the leu and glt genes resulted in the largest increase in product fluxes. This increase in production due to deletion of leuA and gltA can be explained by consumption of acetyl-CoA (Figure 2; 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate + acetyl-CoA + H2O → (2S)-2-isopropylmalate + coenzyme A + H+; oxaloacetate + acetyl-CoA + H2O → citrate + coenzyme A + H+). MoMA also reflected some essential genes like suc and glyA as potential gene deletions for improved titers. These genes are responsible for conservation of CoA (2-oxo-glutarate + CoA + NAD+ → succinyl-CoA + CO2 +NADH) and L-serine (L-serine + tetrahydrofolate → glycine +5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate + H2O) for cysteine production, respectively. L-lysine formation is known to consume glucose-6-phosphate in an alternative pathway to fructoselysine phosphate (D-glucose-6-phosphate + L-Lysine → Fructoselysine 6-phosphate + H2O). As glucose-6-phosphate is essential for L-serine production, deletion of lysA and lysP improves anguibactin titer. Other acetyl-CoA flux improvement gene deletions include removal of icd (more D-threo-isocitrate in the tricarboxylic acid [TCA] cycle for improved acetyl-CoA) and brnQ (increased leucine and isoleucine transport into the cytosol to avoid acetyl-CoA consumption). For every molecule of anguibactin, three molecules of ATP are required. Therefore, ATP conservation through deletion of energy-dependent transporter genes glnH, glnP, and glnQ, which encode for L-glutamate transport from the periplasm to cytosol, improves anguibactin titers.

The leu gene deletion showed the highest improvements in bacillibactin flux again due to conservation of acetyl-CoA. As three ATP molecules are needed to form a molecule of bacillibactin, ATP conservation is effected through deletion of the aas gene (ATP + acyl-carrier protein + 2,3,4-saturated fatty acid → 2,3,4-saturated fatty acyl-[acp] + AMP + diphosphate). MoMA additionally predicted ptsI (an essential gene) and ptsH gene deletions toward conservation of phosphoenolpyruvate that can make more oxaloacetate essential for L-threonine biosynthesis (phosphoenolpyruvate + N-acetyl-D-glucosamine → N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate + pyruvate). In our models, the availability of glycerol promotes pyruvate formation needed for cell growth; hence deletion of the ptsI gene does not affect growth rates. One of the major side reactions that affect bacillibactin production is the consumption of acetyl-CoA for arginine formation, which could otherwise be used for L-threonine biosynthesis. Therefore, prediction of the argA gene deletion for enhanced bacillibactin production comes as no surprise (L-glutamate + acetyl-CoA → N-acetyl-L-glutamate + CoA + H+). The argA deletion additionally conserves L-glutamate necessary for L-threonine biosynthesis. The ilvE gene encodes for an important rate-limiting step in L-isoleucine biosynthesis that conserves L-glutamate for use in L-threonine biosynthesis ((S)-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoate + L-glutamate → 2-oxoglutarate + L-isoleucine).

Vibriobactin's flux, like the previous two compounds, improves upon deletion of leu genes due to conservation of acetyl-CoA useful for L-threonine biosynthesis. The ilvD gene deletion reduces 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate available for reaction with L-glutamate, hence improving L-glutamate flux useful for L-threonine biosynthesis ((R)-2,3-dihydroxy-3-methybutanoate → 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate + H2O; 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate + L-glutamate → L-valine + 2-oxoglutarate). As three ATP molecules are required toward vibriobactin production, deletion of the ppk, adk, prs, and cmk genes improves vibriobactin flux. The ppk and adk genes encode for reactions ATP + diphosphate → ADP + inorganic triphosphate and AMP + ATP → 2 ADP, respectively.

The virulence of P. aeruginosa is mainly activated by phosphate starvation, which triggers three different responses, primarily resulting in pyoverdine generation (Zaborin et al., 2009). Thus, in this study we analyze pyoverdine gene deletion targets under phosphate-limiting conditions. There were only five gene deletion targets (pur genes) identified. purH conserves 10-formyltetrahydrofolate necessary for N-formyl-N-hydroxyl-L-ornithine production (10-formyltetrahydrofolate + 5-amino-1-(5-phospho-D-ribosyl)imidazole-4-carboxamide → tetrahydrofolate + 5-formamido-1-(5-phospho-D-ribosyl)-imidazole-4-carboxamide). Hydrogen carbonate essential for L-arginine biosynthesis is conserved through the deletion of purK (5-amino-1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)imidazole + ATP + hydrogencarbonate → N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide + ADP + phosphate +2 H+).

No unique gene deletions were identified for enterobactin. These can be attributed to the depleted environmental or media conditions needed for production in E. coli. Enterobactin is known to have a high Fe(III)-binding constant (Carrano and Raymond, 1979) (1052 M−1), and hence its production is affected only under extremely low iron concentration conditions (<10−52 M).

Different nutrient uptake rates were tested to see if there were any subsequent changes in gene deletions. Glucose and glycerol uptake rates were increased to 10 mmol/gDCW/h and oxygen was increased to 20 mmol/gDCW/h, whereas amino acids were maintained at 0.1 mmol/gDCW/h. The results for anguibactin changed minimally as the leu genes still remained the targets that yielded highest anguibactin. However, the gltA gene was pushed down in priority and argA, which leads to consumed acetyl-CoA toward L-arginine formation, gained predominance in improved anguibactin titers. Results for bacillibactin showed a gene deletion target shift toward icd encoding for D-threo-isocitrate + NADP+ → 2-oxo-glutarate + CO2 + NADPH, which increases acetyl-CoA flux through the TCA cycle. The genes pheA and tyrA made an entry to the top 25 gene deletion targets owing to an increase of chorismate availability for 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate synthesis (chorismate → prephenate). Vibriobactin showed no major change in the top gene deletion targets. Two additional gene targets were added to the pyoverdine list with nutrient uptake change. The gene purA, which encodes for L-aspartate + IMP + GTP → adenylo-succinate + GDP + phosphate + 2H+, conserves L-aspartate necessary for L-threonine formation. Eleven ATP molecules are needed to make one pyoverdine molecule. Hence, the prs gene deletion toward ATP conservation is warranted (ATP + D-ribulose-5-phosphate → 5-phospho-α-D-ribose-1-diphosphate + AMP + H+). Overall, increased nutrient uptake increased the link between siderophore production and the TCA cycle, thus causing a change in gene deletion targets.

Gene Over-expressions Using OptForce

OptForce was used to identify gene targets that improved compound production upon over-expression. The algorithm makes use of adjustments of reaction bounds that in turn generate a set of reactions for which the upper limits have to be increased (MUSTU set). The gene over-expression targets that influence a direct precursor are considered as “near pathway,” and those that influence the pathway through a series of side reactions are termed as “far pathway.” The results are presented in Table S1 with key targets highlighted qualitatively across Figures 3 and 4.

Anguibactin had many “near pathway” over-expression targets. The genes serA/serB/serC that encode for L-serine synthesis required for L-cysteine production were identified as one of the primary targets. The cysC/cysN/cysD/cysI/cysJ targets that encode for the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway increase precursor flux. The purA/purB and prs results are part of the superpathway of histidine biosynthesis, which increases the L-histidine precursor and ATP. ATP has been mentioned earlier to be vital for production of anguibactin. Increased sulfite production for L-cysteine biosynthesis is achieved through the grxA/grxB/grxC/grxD targets. In the pentose phosphate pathway, D-erythrose-4-phosphate flux is improved using talA/talB. Increased chorismate and, in turn, increased 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate is affected through over-expressions of the aro and ent genes. Acetyl-CoA increases with an increased flux of 3-phospho-D-glycerate on the glycolysis pathway achieved through over-expression of the pgk gene. Some “far pathway” influences include the ompN/ompC/ompF genes that encode for various transport mechanisms essential for cell functioning. The genes nupC/nupG are responsible for nucleoside and proton transport, which influences anguibactin as can be seen through media optimizations with identification of cytidine and uridine as flux-improving components.

Bacillibactin has three precursors, L-glycine, 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate, and L-threonine, which help identify “near pathway” targets. The genes purU/folD improved tetrahydrofolate production that, in turn, improves L-glycine production. Over-expression of the aro genes from the chorismate pathway and talA/talB from the pentose phosphate pathway improves 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate production. The target genes alaA/alaC improve L-threonine precursor flux. Improved glucose uptake by over-expression of galP is identified as a “far pathway” target.

The “near pathway” targets for vibriobactin, apart from the aro and ent genes, are the thrA/thrB/thrC genes, which encode for L-threonine biosynthesis. Glycolysis flux improvement genes like glk and gpmA/gpmM, which encode for improved glucose-6-phosphate and 3-phospho-D-glycerate, respectively, were identified for improved 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate production. The tktA/tktB genes are connected to the pentose phosphate pathway, which upon over-expression would increase D-erythrose-4-phosphate to be utilized through the shikimate pathway to make more 2,3-dihdyroxybenzoate. The “far pathway” targets identified were similar to anguibactin.

Pyoverdine production depends on serine, tyrosine, threonine, lysine, and arginine as important precursors. “Near pathway” targets included pgl, eno, and gapA genes that improve glycolysis pathway flux for serine and tyrosine generation. L-threonine biosynthesis was improved through thrA/thrB/thrC over-expression, whereas L-lysine production was improved via dapA/dapB/dapD/dapE/dapF and lysA gene targets. The arg genes identified as a key gene deletion target with anguibactin and bacillibactin have been identified as one of the prime over-expression targets to improve L-arginine productions for increased pyoverdine flux. In addition to omp and nup, the pntA/pntB genes encoding for hydrogen transport have been identified as “far pathway” targets.

No unique “near pathway” over-expression targets were identified for enterobactin except the ent, ser, and aro genes that influence 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate and L-cysteine fluxes. The omp genes were identified as “far pathway” gene targets.

Media Optimization

There are many optimization strategies that reduce the number of experimental designs required to enhance media compositions (Kennedy and Krouse, 1999). Without these strategies, a simple trial-and-error approach would be time consuming and expensive. FBA allows us to constrain the media components within a stoichiometric model. Thus, FBA can be used to computationally predict an enhanced medium composed of amino acids, carbon sources, vitamins, and other nutrients that can then be verified experimentally.

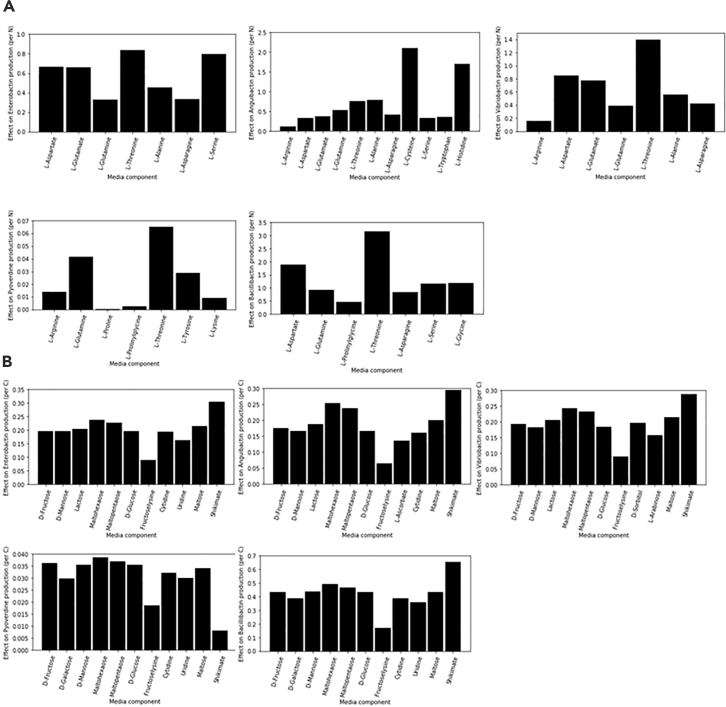

In this work, we have used a Plackett-Burman-based screening comprising the analysis of 7 or 11 components at a time. The screening was applied across nearly 100 components (mole basis) on all the siderophores in this study, and the best media components were hand-picked using statistical criteria (outlined in the Methods section). Tables S2 and S3 demonstrate the general outline the screening utilized for these calculations. Figure 5 shows the various carbon sources and amino acids that most contributed toward improved production.

Figure 5.

Siderophore Computational Medium Optimization

Media screening results from Plackett-Burman analysis in FBA for (A) amino acids and (B) carbon sources normalized per nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) content.

The carbon source that influenced maximum siderophore production was shikimate, an important part of the chorismate pathway essential in many siderophore biosynthetic pathways. This carbon source improves 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate flux, which is one of the precursors needed to make anguibactin, vibriobactin, enterobactin, and bacillibactin. As 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate is not essential for production of pyoverdine, shikimate does not influence pyoverdine production levels. Among more conventional carbon sources, maltohexaose and maltopentaose showed maximum influence on all siderophore products when compared with D-glucose or D-fructose. Apart from these, lactose and maltose showed increased production of all siderophores. Maltohexaose and maltopentaose are expensive compounds (relative to standard medium carbon sources), and hence lactose and maltose may serve as more economical options for increased production.

Anguibactin production showed more pronounced improvements upon increased L-cysteine and L-histidine and minor improvements upon increased L-threonine and L-alanine among amino acids. L-cysteine in one of the direct precursors essential for anguibactin production. L-histidine is known to improve N-hydroxyhistamine, which is one of the precursors for anguibactin biosynthesis (Figure 3). L-threonine is degraded to 2-oxobutanoate, which further degrades to succinyl-CoA to improve acetyl-CoA through the TCA cycle. L-alanine can release CoA from pimeloyl-CoA (S-pimeloyl derivative of coenzyme A), which improves acetyl-CoA flux.

Major amino acids to improve bacillibactin production include L-threonine, L-aspartate, L-glycine, and L-serine. L-threonine is a precursor for bacillibactin production. L-glycine is a precursor for bacillibactin, and hence L-serine, which is converted to L-glycine, serves as an important media component to boost production. The pathway conversion of oxaloacetate to L-threonine includes amino acids like L-aspartate (Figure 3).

The media components identified for vibriobactin are similar to bacillibactin due to two matching precursors, L-threonine and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. In addition, norspermidine made from L-aspartate is an important precursor that explains the identification of L-aspartate and L-glutamate as parameters to improve vibriobactin production.

Enterobactin is made from L-serine and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. There is no TCA cycle/acetyl-CoA involvement in its biosynthesis. Therefore the identification of L-threonine, L-aspartate, and L-glutamate as boosting media components is unexpected. One possible explanation could be degradation of L-threonine (which can be made from L-aspartate and L-glutamate) into L-glycine, which in turn converts to L-serine.

The identification of L-threonine, L-tyrosine, L-lysine, and L-arginine as production boosters for pyoverdine comes as no surprise, as all these amino acids are biosynthetic precursors. L-glutamine has also been identified due to its importance in the formation of L-2,4-diaminobutanoate and N-formyl-N-hydroxyl-L-ornithine (Figure 4). Additional source code and raw data for the computational approaches of this study are included as Data S1.

Limitations of the Study

Steady-state FBA has disadvantages when compared with real-time variable flux values within microorganisms. This includes, to some extent, the actual effects on growth rates, which must be verified experimentally upon the implementation of predicted targets and, theoretically, should be mitigated by using approaches such as MoMA. The steady-state approach attempts to mimic an average growth flux throughout the organism's life cycle to predict the net product yield. In reality, a living microorganism continues to have flux changes throughout its life cycle, and hence a dynamic steady-state FBA is more accurate. However, the constraints of memory and computational time make it difficult to solve the multiple differential equations required for dynamic FBA.

In a similar fashion, stoichiometric models cannot provide insight into metabolism kinetics or associated regulatory networks. Regulation in particular is strongly associated with secondary metabolite natural products (with external signals shifting cellular biosynthesis). As siderophores share biosynthetic steps associated with secondary metabolite natural products, they will likely be subjected to the same regulatory elements dictating eventual biosynthesis. This issue is lessened when biosynthesis is established within a distant heterologous host, as we describe in this study, because the new host is often chosen to minimize overlapping metabolic and regulatory networks with the native host in an attempt to provide a “cleaner” slate with which engineering can be applied, and as a result, stoichiometric modeling may be more accurate. Likewise, upon implementation of model-based predictions within a heterologous host, regulation elements can be minimized further via user-directed constitutive or inducible gene expression elements specific to the new host.

Conclusions

FBA offers a computational advantage of identifying gene targets and ideal media components by effectively coupling with various algorithms that could otherwise be difficult to analyze experimentally. In short, the approach offers an alternative to a purely experimental route to boost production of natural products. In this study, we identified multiple computational gene targets (deletions and over-expressions) and media parameters to improve production of a variety of siderophore natural products. The concepts of stoichiometric analysis of reactions and genes that are associated with siderophore biosynthesis have been effectively executed with linear programming to economically predict best cellular performance. Future steps would be to experimentally implement the identified gene targets and media component changes for improved heterologous siderophore production in anticipation of a variety of novel applications.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize support from the National Science Foundation (Award No: CBET-1438172) and the University at Buffalo Blue Sky Initiative.

Author Contributions

G.S. and B.A.P. conceived the study and prepared the manuscript. G.S. conducted the research while N.M. and G.E.A.-G. provided technical support.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101016.

Supplemental Information

References

- Alper H., Jin Y.-S., Moxley J., Stephanopoulos G. Identifying gene targets for the metabolic engineering of lycopene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2005;7:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G.J., Vulpe C.D. Mammalian iron transport. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:3241. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznar A., Chen N.W., Rigault M., Riache N., Joseph D., Desmaële D., Mouille G., Boutet S., Soubigou-Taconnat L., Renou J.-P. Scavenging iron: a novel mechanism of plant immunity activation by microbial siderophores. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:2167–2183. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonarius H.P., Hatzimanikatis V., Meesters K.P., de Gooijer C.D., Schmid G., Tramper J. Metabolic flux analysis of hybridoma cells in different culture media using mass balances. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996;50:299–318. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960505)50:3<299::AID-BIT9>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard A.P., Pharkya P., Maranas C.D. Optknock: a bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies for microbial strain optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003;84:647–657. doi: 10.1002/bit.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano C.J., Raymond K.N. Ferric ion sequestering agents. 2. Kinetics and mechanism of iron removal from transferrin by enterobactin and synthetic tricatechols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:5401–5404. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho C.C., Fernandes P. Siderophores as “Trojan Horses”: tackling multidrug resistance? Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:290. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong H., Casagranda S., Giordano N., Cinquemani E., Ropers D., Geiselmann J., Gouzé J.-L. Mathematical modelling of microbes: metabolism, gene expression and growth. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2017;14:20170502. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demain A.L. From natural products discovery to commercialization: a success story. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;33:486–495. doi: 10.1007/s10295-005-0076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feist A.M., Palsson B.O. The biomass objective function. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010;13:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M., Miller P.A., Möllmann U., Claypool W.D., Schroeder V.A., Wolter W.R., Suckow M., Yu H., Li S., Huang W. Targeted antibiotic delivery: selective siderophore conjugation with daptomycin confers potent activity against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii both in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:4577–4583. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M., Krouse D. Strategies for improving fermentation medium performance: a review. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999;23:456–475. [Google Scholar]

- King Z.A., Lu J., Dräger A., Miller P., Federowicz S., Lerman J.A., Ebrahim A., Palsson B.O., Lewis N.E. BiGG Models: a platform for integrating, standardizing and sharing genome-scale models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D515–D522. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer S.M. Iron oxide dissolution and solubility in the presence of siderophores. Aquat. Sci. 2004;66:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan T.A., Chan G.Y.S., LO W.H., Babel S. Physico-chemical treatment techniques for wastewater laden with heavy metals. Chem. Eng. J. 2006;118:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lun D.S., Rockwell G., Guido N.J., Baym M., Kelner J.A., Berger B., Galagan J.E., Church G.M. Large-scale identification of genetic design strategies using local search. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:296. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarleveld T.R., Khandelwal R.A., Olivier B.G., Teusink B., Bruggeman F.J. Basic concepts and principles of stoichiometric modeling of metabolic networks. Biotechnol. J. 2013;8:997–1008. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke M., Marahiel M.A. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth J.D., Conrad T.M., Na J., Lerman J.A., Nam H., Feist A.M., Palsson B.Ø. A comprehensive genome-scale reconstruction of Escherichia coli metabolism—2011. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:535. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth J.D., Thiele I., Palsson B.Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:245. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer B.A., Wang C.C., Walsh C.T., Khosla C. Biosynthesis of yersiniabactin, a complex polyketide-nonribosomal peptide, using Escherichia coli as a heterologous host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:6698–6702. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6698-6702.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan S., Suthers P.F., Maranas C.D. OptForce: an optimization procedure for identifying all genetic manipulations leading to targeted overproductions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond K.N., Carrano C.J. Coordination chemistry and microbial iron transport. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:183–190. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk I.J. Siderophore-antibiotic conjugates: exploiting iron uptake to deliver drugs into bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018;24:801. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D., Vitkup D., Church G.M. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232349399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Ranganathan S., Fowler Z.L., Maranas C.D., Koffas M.A. Genome-scale metabolic network modeling results in minimal interventions that cooperatively force carbon flux towards malonyl-CoA. Metab. Eng. 2011;13:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborin A., Romanowski K., Gerdes S., Holbrook C., Lepine F., Long J., Poroyko V., Diggle S.P., Wilke A., Righetti K. Red death in Caenorhabditis elegans caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:6327–6332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813199106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Boghigian B.A., Armando J., Pfeifer B.A. Methods and options for the heterologous production of complex natural products. Nat. Product Rep. 2011;28:125–151. doi: 10.1039/c0np00037j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.