Abstract

Purpose of review

This study aimed to review how digital health has been used for STI/HIV prevention, testing, and treatment.

Recent findings

A scoping review was conducted by searching five databases for peer-reviewed literature published between March 2018 to August 2019. 23 out of 258 studies met the inclusion criteria and were assessed. Six studies used digital platform to enhance STI/HIV prevention messaging; four studies found that digital health can provide vivid promotional information and has been instrumental in increasing the accessibility and acceptability of STI/HIV testing; three studies reported digital health provides a channel to understand and interpret the discourses on PrEP and increase PrEP uptake; three studies focused on refining big data algorithms for surveillance; four studies reported on how digital interventions could be used to optimize clinical Interventions; and four studies found digital interventions can be used to assist mental health services.

Summary

Digital health is a powerful and versatile tool that can be utilized in the production of high-quality, innovative strategies on STIs and HIV services. Future studies should consider focusing on strategies and implementations that leverage digital platforms for network-based interventions, in addition to recognizing the norms of individual digital intervention platforms.

Keywords: Digital Health, HIV, Intervention, STI

Introduction

Innovative prevention tools are urgently needed to unload the high burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in low- and middle- income countries[1]. Social media or digital health provide effective and expansive platforms that deliver STI/HIV services. Digital health services are, currently, Web 2.0 Internet-based applications, they facilitate and help blossom social networks online through profile connection between individuals and/or among groups [2]. Digital health is increasingly being utilized as a conduit for social interactions [3]. With the advancements in technology and increased availability and access to the internet, media platforms have become an integral part of our daily life. People now use digital platforms to seek health care, to explore entertainment options, and even seek sexual partners. Online media platforms also allow people to easily create and share messages without bounds or time restrictions [4]. The versatility of social media features has allowed public health authorities to adopt and apply these technologies to improve sexual health services. As a result, digital health is used in disease surveillance and public health interventions [5]. For example, the US CDC has started to use Facebook to educate the public about vaccinations, and the NIH has funded numerous digital health research studies that explore how digital platforms can be used to improve health care services.

More digital intervention approaches are being developed, piloted, implemented, and evaluated for STI/HIV prevention [6]. Recent applications include digital interventions for condom promotion, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) education and demand generation, STI/HIV testing access improvement, linkage to care, and treatment [7]. In this scoping review, we systematically reviewed how digital health has been used for STI/HIV prevention, testing, and treatment by putting together the latest evidence (studies published since 2018).

Methods

Search Strategy

A scoping review method was selected to identify peer-reviewed literature; this method provides a clear and thorough way to draw conclusions about rapidly developing research areas [8]. In order to accurately and clearly describe the fast-growing nature of digital health, we set the date criterion of the search for published articles between January 2018 and August 2019. In addition, search terms were selected based on their relevance to the search topic to expand the range of literature. Search terms included “social media”; “Facebook”; “Twitter”; “Instagram”; “Youtube”; “Wechat”; “e-health”, “digital health” and “artificial intelligence” in combination with the following terms: “sexually transmitted infections”; “sexual diseases”; “sexual health”; “HIV”; “Chlamydia”; “HPV”; “Gonorrhoea”; “Herpes”; “Syphilis”. The database used were: Pubmed, Embase, MEDLINE (Ovid), and Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Selection Criteria

Initial search retrieved 258 non-duplicate studies from the five databases between January 2018 and August 2019. After duplicates were removed, two authors (B.C. and H.B.) searched the title and abstract to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. All studies were reviewed separately and then jointly, to decide the final included studies. If it was not clear whether an article should be included, three authors (B.C., H.B., and W.T.) reviewed the full texts to discuss its eligibility and reached a consensus decision. Studies were only included if they evaluated the effectiveness of the digital intervention in preventing the transmission of STI/HIV or in improving access to care for people infected with STI/HIV. We excluded studies in which digital platforms were only used as a marketing platform for recruiting participants or for advertising. In addition, conference abstracts, non-English publications, and commentaries were also excluded.

Data Extraction

We used a standardized extraction form in Microsoft Excel, to extract the following information: first author, study design, publication date, target audience, the role of digital health, evaluation methods, intervention domains, and outcomes. The study intervention domains were further categorized into the following subcategories: (1) STI/HIV prevention messaging (promoting condom use, peer-led, theory-based, crowdsourcing digital interventions); (2) STI/HIV testing service (increasing the access to STI/HIV testing, online consultation with physicians); (3) PrEP (discourses on PrEP, PrEP monitoring, promote PrEP uptake); (4) Big data (monitoring and forecasting AIDS, epidemic surveillance, artificial intelligence for HIV prevention); (5) Care-related interventions to optimize clinical interventions; and (6) assist mental health services.

Results

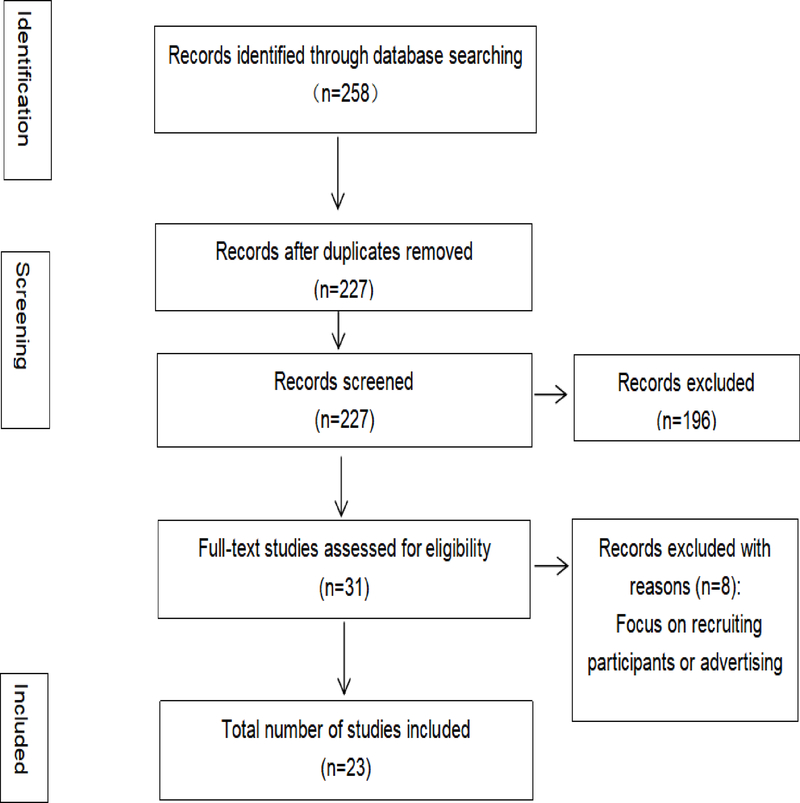

The initial search retrieved 227 non-duplicate studies from January 2018 to August 2019. 196 articles were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract, leaving 31 articles; 8 were excluded after reading the full text. Thus, a total of 23 studies were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1,

Flowchart of the review (Original)

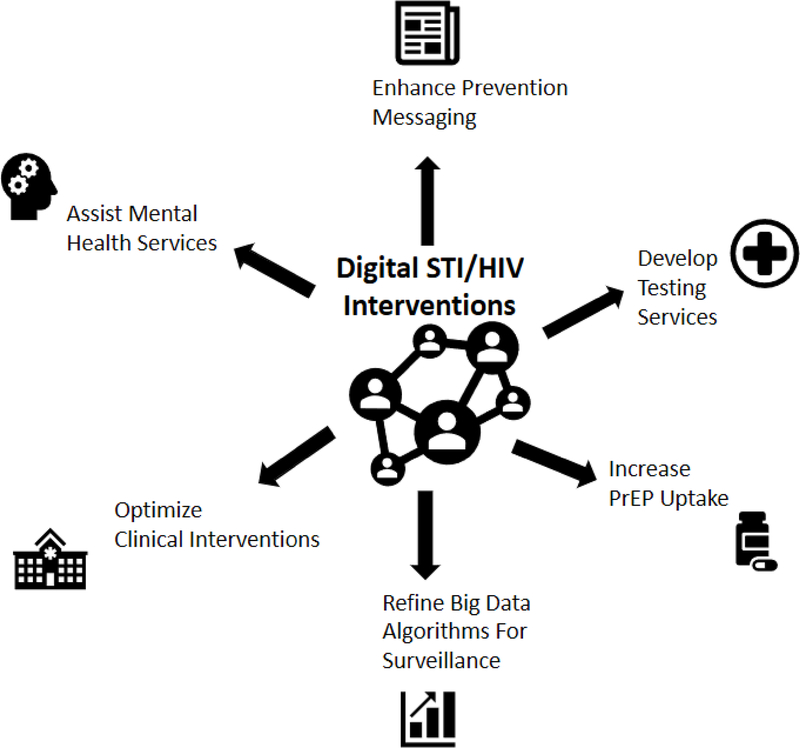

Among the included studies, six focused on enhancing STI/HIV prevention messaging, four focused on developing testing services, three focused on PrEP, three focused on big data approach for prevention and surveillance, three focused on improving medication adherence, and four focused on assisting mental health services(Figure 2). A summary of the studies included in this review is presented in Appendix 1.

Figure 2,

Type of digital STI/HIV interventions (Original)

1. Enhance prevention messaging

Consistent condom use is one of the most effective ways to prevent STI/HIV transmission. Promoting condom use through disseminating health messages has been within the repertoire in traditional sexual health promotion. Digital intervention is endorsed as one of the most effective ways to reach young adults [9]. Innovative health practitioners and researchers have developed digital interventions with different messaging approaches, such as peer-led, theory-based, and crowdsourcing digital interventions. In peer-led digital interventions, social media users with a large number of followers or networks are recruited as peer-leaders to advocate their peers about adopting healthy sexual behaviors. Theory-based digital interventions often leverage behavioral theories to guide their implementation. The crowdsourcing approach derives its intervention contents from collecting the wisdom of the crowds through challenge contests.

The digital peer-led intervention has been applied to prevent and reduce STI/HIV transmission and improve sexual health in secondary schools (STASH) [10]. Peer-led is a persuasive approach for health promotion, especially for young people. Forsyth et al.(2018) identified the most influential students and asked them to spread sexual health information in their friendship groups via digital platforms [10]. Moreover, given the risks of increased STI/HIV, the peer-led intervention has also been used to promote safe usage of dating apps, which is popular among young adults [11].

A variety of theories have been applied in digital interventions, such as health belief models, the theory of planned behavior [12], protection motivation theory [13], and unified theory of behavior (UTB) [14]. Although these conceptual frameworks are not born in the era of digital health, they provide systematic guidance to the development of new digital interventions for sexual health education. For instance, researchers have adopted UTB, which emphasizes the role of intention in the behavior adoption of sexual health programs, to compare the effectiveness of different technology delivery modalities (short messaging system, web-based desktop chatting, and mobile phone chatting) [14].

Crowdsourcing intervention is an innovative approach to use digital platforms for intervention. Digital platforms allow people to obtain wisdom from crowds and collect feedback from participants. Crowdsourcing digital interventions can scale up the target populations’ engagement by asking participants to contribute to the intervention, which turns the passive status of participants into the active status of users. Diverse applications of crowdsourcing approaches have been found in soliciting images, videos, songs, stories, or policy suggestions from crowdsourcing contests [15,16]. In addition, Tang et al.’s review (2019) found that crowdsourcing is an effective, low-cost approach for improving condom use among key populations [17].

2, Developing STI/HIV testing services

Digital platforms have increased overall access to STI/HIV testing services. According to the 5A model (access, availability, appropriateness, acceptability, and applicability), digital health can contribute to all these aspects of care to provide better STI/HIV services [18]. Digital interventions can also provide vivid promotional information (e.g., images and videos); they have been instrumental (e.g., nearby testing sites) in increasing MSM’s accessibility and acceptability of STI/HIV testing [16]. Practices that provide HIV self-testing kit requests or rapid STI testing services, through digital platforms, increase the availability, applicability, and affordability of STI/HIV testing [19]. Furthermore, digital platforms allow patients to have online consultation/online communication services with physicians to increase the adequacy and appropriateness of STI/HIV testing access [20].

Additionally, in digital intervention, geolocation-based text messaging functionality is used to facilitate the effectiveness of reaching target populations. In China, the gay-dating app was utilized in combination with the push-notification platform and geolocation capabilities in digital intervention, to promote STI/HIV testing [21]. One-time mass message push, through the application’s private message functionality was used. Users who accessed the links in the advertising message were redirected to a cellular phone number–which was based on an online appointment system, where they could schedule an onsite testing behavior. Another digital intervention, named WeCare, also used Facebook, texting, and GPS-based mobile social and sexual networking applications, to improve STI/HIV-related care engagement and health outcomes [22].

Research in STI/HIV testing promotion has entered the digital intervention arena to optimize its impact. Studies have compared different digital platforms to examine their effectiveness in increasing HIV testing. For instance, Jones et al. compared the dissemination of campaign messages, through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, among young black men. Their study found that Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat worked well for spreading and promoting information. However, Facebook was not preferred because young people use Facebook less frequently, and Facebook is often viewed as a more family-oriented site; thus, sharing HIV-related messages could be stigmatizing [7]. In addition, studies have also combined digital interventions with other channels to maximize the effect of promoting STI/HIV testing[23].

Digital platforms can provide channels to facilitate communication between vulnerable populations like MSM and STI/HIV physicians, which can help facilitate offline visits. Studies have found that young people are interested and willing to use an MSM-friendly physician finder function embedded within a gay mobile app [20]. Consulting physicians online or using digital health can increase the adequacy of patients’ access to STI/HIV information and encourage appropriate decisions associated with STI/HIV testing or treatment.

3, Increasing PrEP Uptake

The digital platform provides a channel for public health professionals to understand and interpret the discourses on PrEP. Many studies have examined digital conversations and discussions about PrEP. One research used a data mining strategy to analyze the Twitter discourse on PrEP awareness, including expressed opinions, perceived barriers, and key discussion points on its adoption [24–26]. Such studies could support public-health professionals and policymakers in PrEP monitoring, and inform decision making and strategy planning, for efficient HIV combination prevention [24].

The digital platform has also been used to implement interventions that promote PrEP uptake. Patel et al. (2018) used social media to provide education about PrEP, increase motivation to use PrEP, and facilitate access to PrEP [27]. Interventions on PrEP have good reaching effects in most of the studies done on it, including the PrEP4Love (P4L) campaign in Chicago, which got 6,970,127 views on Facebook and 1,719,446 views through Instagram in three months [28].

4. Refining big data algorithms for surveillance

Digital platforms construct part of the big data of e-health. Mining digital messages and updates can help, in real-time data, to learn and understand the physical and emotional state of people who are at risk of STI/HIV infection. Nan and Gao (2018) used search engine data (Baidu) to monitor and forecast AIDS in China[29], and Young and Zhang (2018) performed a similar study using Google in the US. Through timed series data[30], both studies found that machine learning methods can lead to the estimation of AIDS incidences and death.

The potential of using the digital platform as a data source for epidemic and emotional surveillance has also been adopted [31]. Furthermore, using artificial intelligence (AI) for HIV prevention is also promising. A recent study examined the feasibility of using peer change agents (PCAs), selected via the AI algorithm, to deliver HIV prevention messages among youth experiencing homelessness [32]. AI-enhanced PCA intervention proved a feasible method for engaging youth.

5, Optimizing Clinical Interventions

STI/HIV clinical interventions refer to the care-related interventions that take place after diagnosis with STI/HIV, including linkage to care, adherence to medication, and retention. A mainstream approach is to use mHealth technologies (i.e., mobile health technologies that leverage mobile apps) to improve medication adherence among people living with STI/HIV. Studies have suggested the need for using digital platforms to monitor adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy [33]. Guo et al. (2018) used digital platform to send weekly reminders to participants to remind them about medication uptake [34]. In a study conducted in Florida, among the 132 people living with HIV (PLWH), 70.2% (n=92) reported their interest in receiving daily medication adherence reminders via an app [35].

In addition, gamification is becoming a widely used method to improve adherence. Game-based interventions are often implemented in designing interactive technology-based adherence interventions. Such video games have been found to improve adolescents’ and young adults’ ART adherence. Gamification components have also been included in other interventions such as the Thrive with Me intervention, to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among MSM [36]. Gaming design can evoke peer influence and draw on people’s intrinsic motivation to engage with the intervention [36].

6, Assisting mental health services

Digital interventions are also being increasingly used as a tool in mental health improvement. Studies have been found that using digital platforms can significantly decrease perceived stress and depression among youth living with HIV [37]. digital interventions used to reduce anxiety and depression can enhance ARV adherence [34]. To improve PLWH’s mental health, Guo et al. (2018) conducted a digital intervention to motivate PLWH to engage in physical activities. In this intervention, digital platforms were not only used to deliver a cognitive-behavioral stress management course and also track and monitor progress with timely feedback and rewards [38]. The digital platform is the avenue for MSM or PLHIV to seek informational, instrumental and emotional social support, especially those who face challenges dealing with HIV [39]. One study found that social media friends provided more social support for PLHIV compared to offline friends [40].

Additionally, STI/HIV patients have reported favoring technology use for mental health, such as video conferencing with a counselor [41]. The ease of accessing mental health support is an important mechanism to achieve STI/HIV treatment engagement [41]. Digital health can overcome many of the barriers to care by increasing the accessibility of consultation and counseling. Wootton et al. (2019) proposed a protocol to develop telehealth counseling intervention that identified and problem-solved the challenges of barriers that prevent access to HIV care and adherence as well as mental health issues [42].

Suggestions and conclusions

First, digital intervention provides useful STI/HIV services that can be scaled up, especially in low-to-middle income countries. Numerous studies have examined the feasibility and acceptability of digital interventions, and a couple of RCTs have been conducted to investigate their effectiveness. Recent studies have also focused on the optimization and maximization of the effects of digital interventions. Further strategies that aim to scale-up digital intervention for STI/HIV prevention are needed.

Second, the role of digital health at the community level requires more examination. Studies have investigated how digital health was used to reduce STI/HIV infections at an individual level. However, studies that aim to explore and evaluate its role at the community level are still lacking. Studies should consider evaluating the effectiveness of digital interventions at the community level.

Third, digital health can be used as an efficient tool for STI/HIV surveillance. Since people often use digital platforms for communication across the globe, digital platforms may help enhance STI/HIV surveillance and provide real-time behavior monitoring of key populations and PLWHA [43].

Fourth, digital interventions should carefully take the features of the platforms into consideration. digital platforms are not created equal. Although social networks on these platforms are often perceived to exert peer influence on others to promote health behavior, studies have suggested that some platforms such as Facebook are not a preferred platform for sharing STI/HIV prevention content [44]. Future digital interventions are suggested not to ignore the norms of individual digital platforms.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Summary of included studies in the review (n=23)

Key points.

Digital health is a useful and powerful tool that can be used to improve STI/HIV prevention services

Digital health has been used to enhance prevention messaging, develop testing service, increase PrEP uptake, refine big data algorithms for surveillance, optimize clinical intervention, and assist mental health services

Future studies on scaling-up digital interventions and evaluating its role at the community level

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0103800), the National Institutes of Health (NIAID R01AI114310, NIAID K24AI143471), UNC Center for AIDS Research (NIAID 5P30AI050410), NIMH (R34MH109359 and R34MH119963), National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX10101-001-001-003), NSFC (81903371), National Social Science Foundation of China (18CXW017), Shenzhen University Grant (18QNFC46), and Foundation for Distinguished Research Groups in Higher Education of Guangdong, China (2018WCXTD015). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- [1].WHO. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed September 28, 2019).

- [2].Obar JA, Wildman SS. Social Media Definition and the Governance Challenge: An Introduction to the Special Issue. SSRN Electron J 2015. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2647377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kass-Hout TA, Alhinnawi H. Social media in public health. Br Med Bull 2013;108:5–24. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldt028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lin R, Utz S. Self-disclosure on SNS: Do disclosure intimacy and narrativity influence interpersonal closeness and social attraction? Comput Human Behav 2017;70:426–36. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Charles-Smith LE, Reynolds TL, Cameron MA, Conway M, Lau EHY, Olsen JM, et al. Using social media for actionable disease surveillance and outbreak management: A systematic literature review. PLoS One 2015;10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Tang W, et al. Social Media Interventions to Promote HIV Testing, Linkage, Adherence, and Retention: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e394. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jones J, Carter B, Wilkerson R, Kramer C. Attitudes toward HIV testing, awareness of HIV campaigns, and using social networking sites to deliver HIV testing messages in the age of social media: a qualitative study of young black men. Health Educ Res 2019;34:15–26. doi: 10.1093/her/cyy044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fernandez SB, Howard M, Hospital M, Morris SL, Wagner EF. Hispanic Students’ Perceptions About HIV/STI Testing and Prevention: A Mixed-Methods Study in a Hispanic-Serving University. Health Promot Pract 2018. doi: 10.1177/1524839918801590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Forsyth R, Purcell C, Barry S, Simpson S, Hunter R, McDaid L, et al. Peer-led intervention to prevent and reduce STI transmission and improve sexual health in secondary schools (STASH): protocol for a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2018;4:180. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0354-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lau STH, Choi KWY, Chen J, Mak WPH, Yeung HKCA, Tucker J, et al. Study protocol for a peer-led web-based intervention to promote safe usage of dating applications among young adults: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019;20. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Z, Yang L, Hao C, Jiang H, Zhu J, Luo Z, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating Efficacy of a Brief Setting-Based and Theory-Based Intervention Promoting Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Among Heterosexual Male Sexually Transmitted Disease Patients in China. AIDS Behav 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02610-9.* This study focused on voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), which is an evidence-based biomedical HIV prevention but under-utilized by male sexually transmitted diseases patients (MSTDP) in China.

- [13].Havaei M, Salehi L, Akbari-Kamrani M, Rahimzadeh M, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S. Effect of education based on protection motivation theory on adolescents’ reproductive health self-care: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2019. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2018-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Levitz N, Wood E, Kantor L. The influence of technology delivery mode on intervention outcomes: Analysis of a theory-based sexual health program. J Med Internet Res 2018;20. doi: 10.2196/10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, Wu D, Li KT, Lu H, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: A closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLOS Med 2018;15:e1002645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002645.** This study used a rigorous RCT design to examine an innovative - crowdsourcing approach to promote HIV testing in eight cities in China. Digital health tools were adopted for multiple purposes, including soliciting ideas from target popular to design intervention messages, recruiting and retaining study participants, delivering intervention messages and providing HIV self-testing kits, etc.

- [16].Fitzpatrick T, Zhou K, Cheng Y, Chan P-L, Cui F, Tang W, et al. A crowdsourced intervention to promote hepatitis B and C testing among men who have sex with men in China: study protocol for a nationwide online randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:489. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tang W, Ritchwood TD, Wu D, Ong JJ, Wei C, Iwelunmor J, et al. Crowdsourcing to Improve HIV and Sexual Health Outcomes: a Scoping Review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2019;16:270–8. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00448-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jiang LC, Wang Z-Z, Peng T-Q, Zhu JJH. The divided communities of shared concerns: mapping the intellectual structure of e-Health research in social science journals. Int J Med Inform 2015;84:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wray T, Chan PA, Simpanen E, Operario D. eTEST: Developing a Smart Home HIV Testing Kit that Enables Active, Real-Time Follow-Up and Referral After Testing. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2017;5:e62. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cao B, Zhao P, Bien C, Pan S, Tang W, Watson J, et al. Linking young men who have sex with men (YMSM) to STI physicians: a nationwide cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:228. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3145-2.* This study examined online STI/HIV information-seeking behaviors among young men who have sex with men (YMSM). This study also linked their online STI/HIV information-seeking behaviors with offline physician visits.

- [21].Wang L, Podson D, Chen Z, Lu H, Wang V, Shepard C, et al. Using Social Media To Increase HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Beijing, China, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:478–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6821a3.** This study highlights combining geosocial networking platforms and advertisements for HIV testing services can be an effective strategy to increase the number of MSM who obtain HIV testing.

- [22].Tanner AE, Song EY, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, Schafer K, Ware S, et al. Preliminary Impact of the weCare Social Media Intervention to Support Health for Young Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:450–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Swendeman D, Arnold EM, Harris D, Fournier J, Comulada WS, Reback C, et al. Text-Messaging, Online Peer Support Group, and Coaching Strategies to Optimize the HIV Prevention Continuum for Youth: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2019;8:e11165. doi: 10.2196/11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kakalou C, Lazarus J V, Koutkias V. Mining Social Media for Perceptions and Trends on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019;264:959–63. doi: 10.3233/SHTI190366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McLaughlin ML, Hou J, Meng J, Hu C-W, An Z, Park M, et al. Propagation of Information About Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention Through Twitter. Health Commun 2016;31:998–1007. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1027033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schwartz J, Grimm J. PrEP on Twitter: Information, Barriers, and Stigma. Health Commun 2017;32:509–16. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1140271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Patel V V, Ginsburg Z, Golub SA, Horvath KJ, Rios N, Mayer KH, et al. Empowering With PrEP (E-PrEP), a Peer-Led Social Media-Based Intervention to Facilitate HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Adoption Among Young Black and Latinx Gay and Bisexual Men: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7:e11375. doi: 10.2196/11375.* This protocol aimed to develop and pilot test a theoretically grounded, social media-based, peer-led intervention to increase PrEP uptake in young black and Latinx, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.(*)

- [28].Dehlin JM, Stillwagon R, Pickett J, Keene L, Schneider JA. #PrEP4Love: An Evaluation of a Sex-Positive HIV Prevention Campaign. JMIR Public Heal Surveill 2019;5:e12822. doi: 10.2196/12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nan Y, Gao Y. A machine learning method to monitor China’s AIDS epidemics with data from Baidu trends. PLoS One 2018;13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Young SD, Zhang Q. Using search engine big data for predicting new HIV diagnoses. PLoS One 2018;13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199527.* This study found that using actively searching data online is a feasible and timely tool to predict new cases of HIV.(*)

- [31].Karmegam D, Ramamoorthy T, Mappillairajan B. A Systematic Review of Techniques Employed for Determining Mental Health Using Social Media in Psychological Surveillance During Disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rice E, Yoshioka-Maxwell A, Petering R, Onasch-Vera L, Craddock J, Tambe M, et al. Piloting the use of artificial intelligence to enhance HIV prevention interventions for youth experiencing homelessness. J Soc Social Work Res 2018;9:551–73. doi: 10.1086/701439.** This is an early piece that used an artificial intelligence (AI) approach to assist HIV prevention.(**)

- [33].Bychkov D, Young S. Social media as a tool to monitor adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Transl Res 2018;3:407–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guo Y, Xu Z, Qiao J, Hong YA, Zhang H, Zeng C, et al. Development and Feasibility Testing of an mHealth (Text Message and WeChat) Intervention to Improve the Medication Adherence and Quality of Life of People Living with HIV in China: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018;6:e10274. doi: 10.2196/10274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Morano JP, Clauson K, Zhou Z, Escobar-Viera CG, Lieb S, Chen IK, et al. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Willingness Toward the Use of mHealth Tools for Medication Adherence in the Florida mHealth Adherence Project for People Living With HIV (FL-mAPP): Pilot Questionnaire Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019;7:e12900. doi: 10.2196/12900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Horvath KJ, Amico KR, Erickson D, Ecklund AM, Martinka A, DeWitt J, et al. Thrive With Me: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial to Test a Peer Support Intervention to Improve Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7:e10182. doi: 10.2196/10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sayegh CS, MacDonell KK, Clark LF, Dowshen NL, Naar S, Olson-Kennedy J, et al. The Impact of Cell Phone Support on Psychosocial Outcomes for Youth Living with HIV Nonadherent to Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3357–62. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Guo Y, Hong YA, Qiao J, Xu Z, Zhang H, Zeng C, et al. Run4Love, a mHealth (WeChat-based) intervention to improve mental health of people living with HIV: A randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2018;18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5693-1.** This protocol study promised to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT) aimed at improving mental health in people living with HIV (PLWH) in China.(**)

- [39].Chen L, Guo Y, Shi J. Social Support Seeking on Social Media among Chinese Gay Men Living with HIV/AIDS: The Role of Perceived Threat. Telemed e-Health 2019;25:655–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Han X, Li B, Qu J, Zhu Q. Weibo friends with benefits for people live with HIV/AIDS? The implications of Weibo use for enacted social support, perceived social support and health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2018;211:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Saberi P, Dawson Rose C, Wootton AR, Ming K, Legnitto D, Jeske M, et al. Use of technology for delivery of mental health and substance use services to youth living with HIV: a mixed-methods perspective. AIDS Care 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1622637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wootton AR, Legnitto DA, Gruber VA, Dawson-Rose C, Neilands TB, Johnson MO, et al. Telehealth and texting intervention to improve HIV care engagement, mental health and substance use outcomes in youth living with HIV: a pilot feasibility and acceptability study protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028522. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dong Y, Zhou X, Lin Y, Pan Q, Wang Y. HIV-related posts from a Chinese internet discussion forum: An exploratory study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0213066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Card KG, Lachowsky N, Hawkins BW, Jollimore J, Baharuddin F, Hogg RS. Predictors of facebook user engagement with health-related content for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: Content analysis. J Med Internet Res 2018;20. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Summary of included studies in the review (n=23)