Abstract

Resolvins (Rvs) are highly potent anti-inflammatory lipid mediators that are chemically and biologically unstable because of their polyunsaturated structures. To address this issue, we designed benzene congeners of RvE2, i.e., o-, m-, and p-BZ-RvE2s, as stable equivalents of RvE2 by replacing the unstable skipped diene moiety with a benzene ring on the basis of computational conformation studies and synthesized these congeners via a short common route through two Stille couplings. o-BZ-RvE2 exhibited more potent anti-inflammatory activity and much higher metabolic stability than RvE2. Thus, o-BZ-RvE2 was identified as a stable equivalent of RvE2, which is useful as a lead for anti-inflammatory drugs with a new mechanism of action as well as a biotool for investigating RvE2-mediated inflammation resolving pathways.

Keywords: Resolvin E2, anti-inflammatory, benzene congener, proresolving lipid mediator, stable equivalent, skipped diene

Inflammation is an essential defense mechanism of the body against tissue injury and infections induced by invading microbial pathogens, in which polyunsaturated fatty acid mediators play an important role. For example, some prostaglandins,1,2 which are metabolites of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, are involved in the induction of inflammation. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which reduce prostaglandin production by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX), are widely used in clinical practice for the treatment of various inflammation-related diseases. NSAIDs cause undesirable side effects, however, such as asthma and gastrointestinal and renal disorders, and therefore, the discovery of novel effective anti-inflammatory drugs other than NSAIDs is eagerly anticipated.3,4

Resolvins (Rvs), which are metabolites of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, have recently attracted attention as leads for new anti-inflammatory drugs.5−12 Rvs actively promote the resolution of inflammation by inhibiting neutrophil infiltration and promoting phagocytosis of macrophages in remarkably low doses. Rvs are chemically and biologically unstable because of their polyunsaturated structures,13,14 and therefore, it is important to develop stable equivalents in which the potent anti-inflammatory activity is maintained.

We recently reported cyclopropane congeners of RvE2 (CP-RvE2) as stable equivalents of RvE2 (Figure 1a).15 Because polyunsaturated fatty acids and their lipid mediators are often oxidatively unstable due to their 1,4-diene (skipped diene) structures, the two bisallylic C10 and C13 positions in the skipped diene moieties of RvE2 might be easily oxidized. Therefore, we designed α- and β-CP-RvE2, in which the C11– C12 cis-olefin was replaced with a cis-olefin-bioisosteric cis-cyclopropane to eliminate the oxidatively unstable skipped diene structure. Both α- and β-CP-RvE2 exhibited potent anti-inflammatory activity with improved stability against oxygen compared with RvE2, but the metabolic stability was insufficient. In addition, their synthesis required rather long reaction steps, which resulted in a low total yield.

Figure 1.

(a) Cyclopropane congeners α- and β-CP-RvE2s; (b) NSAIDs as mimics of arachidonic acid.

To develop further valuable equivalents of RvE2, we took notice of the chemical structures of classical NSAIDs (Figure 1b). Many NSAIDs consist of an acidic functional group and a hydrophobic moiety with an aromatic ring, mimicking the terminal carboxylic acid and the polyunsaturated carbon-chain structures of arachidonic acid, which is a major substrate of COX, the target enzyme of NSAIDs. Replacement of the unsaturated structure with an aromatic ring is advantageous in terms of improving stability, controlling the conformation, as well as for synthetic convenience. In addition, we considered that the regio-isomerism depending on the substituting positions on an aromatic ring might be effective for exploring the bioactive conformation to develop highly active and stable RvE2 derivatives, as described below. Through these studies, we successfully identified o-BZ-RvE2 as a highly stable equivalent of RvE2 (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Benzene congeners of LXA4 and RvD1 designed by Serhan; (b) design of BZ-RvE2s by replacing the unstable skipped diene with a benzene ring.

Serhan and co-workers reported o-[9,12]-benzo-ω6-epi-LXA4 and BDA-RvD1 incorporating a benzene ring for lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and RvD1 structure, which have improved metabolic stability while maintaining anti-inflammatory activity (Figure 2a).16,17 In these derivatives, a benzene ring was used as an effective mimic of the 1,3,5-triene structure of LXA4 or RvD1. RvE2 does not have a 1,3,5-triene structure, unlike LXA4 or RvD1; however, we thought that a benzene ring might be useful as a key structure for developing stable equivalent of RvE2 by the molecular design considering conformation of compounds. This is because NSAIDs such as aspirin and loxoprofen including a benzene ring is likely to three-dimensionally mimic arachidonic acid regardless of its nontrienic structure. In addition, RvE2 have a skipped diene structure similarly to arachidonic acid, which is potentially replaced by a benzene ring. Our previous studies of CP-RvE2s suggested that the oxidative instability of RvE2 is due to the two consecutive skipped diene (C8–C15) moieties (Figure 1a). In addition, because both α- and β-CP-RvE2 exhibit potent anti-inflammatory effects in mice, the C11–C12 double bond is not essential for the bioactivity, suggesting that the relative spatial positioning of the C1–C10 and C13–C20 moieties connected by the C11–C12 double bond might be related to the bioactive form (Figure 2b). Taking these results and considerations into account, we devised a strategy to replace the two skipped diene structures by a stable benzene ring in the RvE2 backbone to develop stable RvE2 congeners.

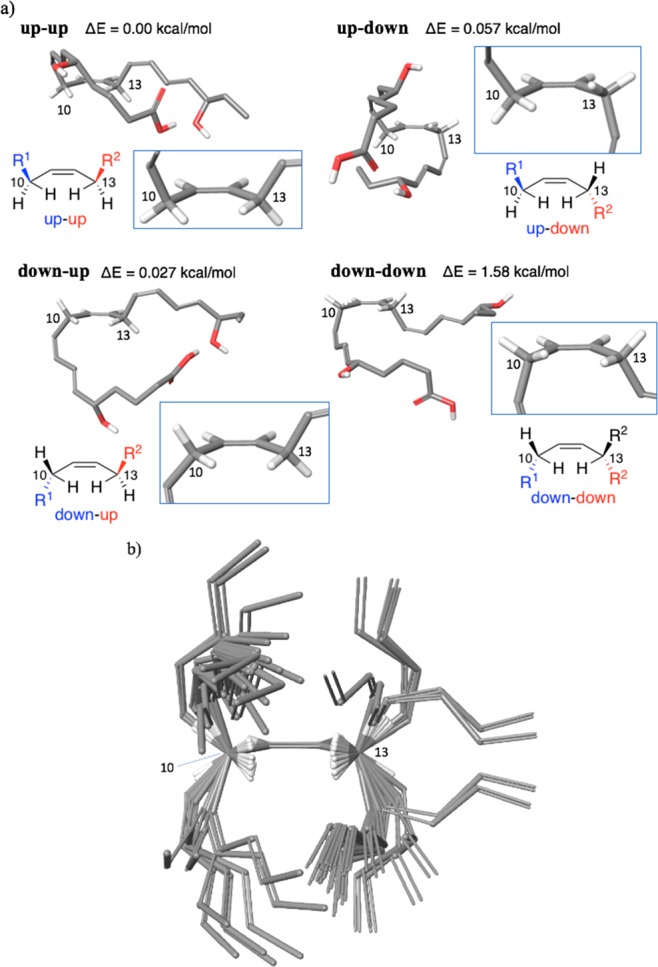

To identify highly potent analogues of a bioactive ligand, it is often effective to mimic the binding conformation to the target biomolecule, i.e., bioactive form. The target molecules of RvE2 and the bioactive form, however, are unclear. Thus, we first investigated stable conformations of RvE2 using calculations (MacroModel 10.9).18 Although the conformation of RvE2 is likely to be rather constrained by the five rigid unsaturated bonds, its backbone can assume conformations differently around the C10 and C13 sp3 carbons. The C9–C10 and C13–C14 single bonds are rotatable; however, because of allylic 1,3-strains, their rotation would be significantly restricted so that the conformations in which the hydrogen atoms at the C10 and C13 sp3 carbons orient inward can be stable. In fact, the calculations suggested that four typical stable rotational isomers around the C10 and C13 carbons avoiding the allylic strains exist within 1.58 kcal/mol from the global minimum conformation, as shown in Figure 3. These four conformers are named up–up, down–up, up–down, and down–down, respectively, based on whether C9 and C14 are up or down with respect to the plane C10–C11–C12–C13 bond of RvE2 (Figure 3a). Accordingly, RvE2 is likely to change its three-dimensional structure, in which the C10 and C13 carbons function like two hinges arranging the C1–C10 and C13–C20 moieties differently in space (Figure 3b). Therefore, we thought that the relative orientation of the C1–C10 and C13–C20 moieties, which is mainly controlled by the two hingelike C10 and C13 carbons, would be key for the anti-inflammatory effects and one of the four conformers might be the bioactive form.

Figure 3.

Stable conformations of RvE2 obtained by calculations. (a) Four typical stable conformations. The figures in the squares are enlarged structures at C10–C13 of each conformation of RvE2. ΔE means the relative potential energy from the global minimum. (b) Superposition of the stable conformers within 2.0 kcal/mol from the global minimum around the hingelike C10 and C13 carbons, in which the C1–C4, C18–C20, and hydroxyl groups are not indicated.

We thought that the hinge-dependent conformers of RvE2 might be mimicked by benzene-introduced RvE2 congeners, which have substitutions at different positions on the benzene ring, and therefore designed o-, m-, or p-BZ-RvE2 (Figure 2b). In these benzene congeners, the special position of the ω-chain corresponding to the C16–C20 moiety of RvE2 is constrained by the benzene ring. Furthermore, the orientation of the carboxy-chain corresponding to the C1–C7 moiety of RvE2 can be restricted because of the steric repulsion between the benzene ring and the ω-chain, just like the allylic strain in RvE2.

The calculated stable conformations of o-BZ-RvE2 are shown in Figure 4. The calculations indicated that o-BZ-RvE2 (1a, Figure 4a) had two typical stable conformations within 3.0 kcal/mol from the global minimum conformation, i.e., up-extended and down-extended forms, which are named based on orientation of C7 (up or down to the plane benzene ring) and that of the C11–C12 double bond (extended or folded), as shown in Figure 4b. These two conformations are mainly due to the rotational barrier around the methylene at the benzyl position, as we expected. The up-extended and down-extended forms of o-BZ-RvE2 within 2.0 kcal/mol from the global minimum conformation were superimposed on the up–up/up–down and down–up/down–down conformers of RvE2, respectively, based on their plane structure moieties (Figures 4c, d). The orientation of the C4–C7 moiety in the up-extended and down-extended forms of o-BZ-RvE2 overlapped very well with the C5–C9 of the up–up/up–down and down–up/down–down conformers of RvE2, respectively. Thus, o-BZ-RvE2 might conformationally mimic RvE2, where the C8 of o-BZ-RvE2 would function as a hinge similarly to the C10 of RvE2.

Figure 4.

Stable conformations of o-BZ-RvE2 (1a) obtained by calculations. (a) Chemical structure of o-BZ-RvE2. (b) Two typical stable conformations. ΔE means the relative potential energy from the global minimum. (c) Superimposition of the up-extended forms of o-BZ-RvE2 (green) on the up–up/down conformers of RvE2 (gray) within 2.0 kcal/mol from the global minimum conformation. (d) Superimposition of the down-extended forms of o-BZ-RvE2 (green) on the down–up/down conformers of RvE2 (gray) within 2.0 kcal/mol from the global minimum conformation.

Also, calculations suggested that m-BZ-RvE2 mimics part of stable conformers of RvE2 (Figure S1).19 We also planned to synthesize p-BZ-RvE2 as a negative control,20 because biological evaluation of the three regioisomers would give some insight into our conformational hypothesis on RvE2 and its benzene congeners described above.

The synthetic strategy common for the three BZ-RvE2s is shown in Figure 5, in which the ω-terminal chain and the carboxy chain were conjugated with the central benzyl core through two Stille coupling reactions. The synthesis is summarized in Scheme 1. The hydroxy group of compound 2(21) was protected with a TBS group to give vinylstannane 3, and then the first Stille coupling of 3 with o-, m-, or p-iodobenzyl alcohol 4a–c afforded the corresponding styrenes 5a–c, respectively. The hydroxy group of 5a–c was mesylated to provide compounds 6a–c, which were then converted to the corresponding benzyl bromides 7a–c. The second Stille coupling of 7a–c with vinylstannane 8(22,23) effectively gave dienes 9a–c, respectively.24 Finally, three types of BZ-RvE2 (1a–c) were obtained by deprotection of 9a–c, respectively, with TBAF.

Figure 5.

Common synthetic plan for the three BZ-RvEs (1a–c).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of BZ-RvE2s (1a–c).

Reagents and conditions: (a) TBSCl, imidazole, DMF, rt, 79%; (b) 4, Pd(PPh3)4, toluene, reflux, 60% (5a), 61% (5b), 46% (5c); (c) MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (d) NaBr, acetone, reflux, 83% (7a), 68% (7b), 75% (7c) for 2 steps; (e) 8, Pd(PPh3)4, DMF, 90 °C, 50% (9a), 58% (9b), 66% (9c); (f) TBAF, THF, rt, 95% (o-BZ-RvE2 (1a)), 72% (m-BZ-RvE2 (1b)), 76% (p-BZ-RvE2 (1c)).

The anti-inflammatory activity of synthesized o-, m-, and p-BZ-RvE2 (1a–c) as well as RvE2 was evaluated using a mouse model of bacteria-induced peritonitis (Figure 6).15,25,26 Intraperitoneal (ip) injection of heat-killed Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes), a Gram-positive bacterium, induced inflammation of the peritoneum, which resulted in a clear increase in the number of neutrophils after 24 h. The number of neutrophils was significantly reduced by ip-administration of 300 pg of RvE2 at 8 h after the P. acnes injection. When the same dose of BZ-RvE2 1a–c (300 pg) was administered, o-BZ-RvE2 exhibited the most potent anti-inflammatory activity, comparable to or even higher than that of RvE2 (Figure 6a). On the other hand, the number of neutrophils observed after m-BZ-RvE2 and p-BZ-RvE2 treatment did not decrease significantly compared with the untreated group. Treatment of inflammation-induced mice with 300 fg, 300 pg, and 300 ng of RvE2 or o-BZ-RvE2 had dose-dependent effects, as shown in Figure 6b. Notably, at a dose of 300 fg, the number of neutrophils in the o-BZ-RvE2 group was significantly lower than that in the RvE2 group. These results demonstrated that o-BZ-RvE2 has more potent anti-inflammatory activity than RvE2 at a low dose. Therefore, o-BZ-RvE2 might mimic the bioactive form of RvE2 with regard to its anti-inflammatory function.27

Figure 6.

(a) Anti-inflammatory activity of RvE2 and BZ-RvE2s injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 300 pg. (b) Dose-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of RvE2 and o-BZ-RvE2.

The metabolic stability of RvE2 and the three BZ-RvE2s (1a–c) was investigated by treating them with human liver microsomes (Figure 7). The remaining rate of RvE2 and p-BZ-RvE2 decreased in a time-dependent manner to less than 40% after 6 h. In contrast, there was almost no decrease in o-BZ-RvE2 and only a slight decrease in m-BZ-RvE2 under the same conditions.28 Thus, o-BZ-RvE2 was remarkably metabolically stable in comparison with RvE2.

Figure 7.

Metabolic stability of RvE2 and the three BZ-RvE2s against human microsomes.

In conclusion, we designed three benzene congeners as stable equivalents of RvE2 by replacing the unstable skipped diene moiety with a benzene ring on the basis of conformational analysis studies. The three congeners were effectively synthesized through two Stille coupling reactions. Among them, o-BZ-RvE2 was not only very stable against human microsomes but also exhibited highly potent anti-inflammatory activity in a mouse model of bacteria-induced peritonitis, and was even more potent than RvE2 at a low dose. Thus, o-BZ-RvE2 was identified as a stable equivalent of RvE2 that can be a valuable lead for anti-inflammatory drugs with a new mechanism of action as well as a useful biotool for investigating RvE2-mediated inflammation-resolving pathways because of its high anti-inflammatory potency and stability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (25860087, H.F.), Scientific Research Grant (C) (17K08360, H.F.), Scientific Research Grants (A) (15H02495 and 19H0101409, S.S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and a research grant from Takeda Science Foundation (H.F.), and partly by Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS) from AMED under Grant JP18am0101093.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00596.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Burstein S. H. The chemistry, biology and pharmacology of the cyclopentenone prostaglandins. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators 2020, 148, 106408. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2020.106408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciotti E.; Fitzgerald G. A. Prostaglandins and Inflammation. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason I.; Scarpignato C.; Holmgren E.; Olszewski M.; Rainsford K. D.; Lanas A. Mechanisms of damage to the gastrointestinal tract from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 500–514. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelle S.; Reichenbach S.; Wandel S.; Hildebrand P.; Tschannen B.; Villiger P. M.; Egger M.; Jüni P. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011, 342, c7086. 10.1136/bmj.c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M.; Aoki-Saito H.; Fukuda H.; Ikeda H.; Koga Y.; Yatomi M.; Tsurumaki H.; Maeno T.; Saito T.; Nakakura T.; Mori Y.; Yanagawa M.; Abe M.; Sako Y.; Dobashi K.; Ishizuka T.; Yamada Y.; Shuto S.; Hisada T. Resolvin E3 attenuates allergic airway inflammation via the interleukin-23–interleukin-17A pathway. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 12750–12759. 10.1096/fj.201900283R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashia P.; Cordella A.; Nobili A.; La Barbera L.; Federici M.; Leuti A.; Campanelli F.; Natale G.; Marino G.; Calabrese V.; Vedele F.; Ghiglieri V.; Picconi B.; Di Lazzaro G.; Schirinzi T.; Sancesario G.; Casadei N.; Riess O.; Bernardini S.; Pisani A.; Calabresi P.; Viscomi M. T.; Serhan C. N.; Chiurchiu V.; D’Amelio M.; Mercuri N. B. Blunting neuroinflammation with resolvin D1 prevents early pathology in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–19. 10.1038/s41467-019-11928-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui Y. D.; Omori K.; Ito T.; Yamashiro K.; Nakamura S.; Okamoto K.; Ono M.; Yamamoto T.; Van Dyke T. E.; Takashiba S. Resolvin D2 induces resolution of periapical inflammation and promotes healing of periapical lesions in rat periapical periodontitis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 307. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte A.; Recchiuti A.; Federti E.; Koehl B.; Mintz T.; El Nemer W.; Tharaux P.-L.; Brousse V.; Andolfo I.; Lamolinara A.; Weinberg O.; Siciliano A.; Norris P. C.; Riley I. R.; Iolascon A.; Serhan C. N.; Brugnara C.; De Franceschi L. Resolution of sickle cell disease- associated inflammation and tissue damage with 17R-resolvin D1. Blood 2019, 133, 252–265. 10.1182/blood-2018-07-865378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulciner M. L.; Serhan C. N.; Gilligan M. M.; Mudge D. K.; Chang J.; Gartung A.; Lehner K. A.; Bielenberg D. R.; Schmidt B.; Dalli J.; Greene E. R.; Gus-Brautbar Y.; Piwowarski J.; Mammoto T.; Zurakowski D.; Perretti M.; Sukhatme V. P.; Kaipainen A.; Kieran M. W.; Huang S.; Panigrahy D. Resolvins suppress tumor growth and enhance cancer therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 115–140. 10.1084/jem.20170681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno Y.; Sato Y.; Fukuda H.; Ishimura K.; Ikeda H.; Watanabe M.; Tansho-Nagakawa S.; Ubagai T.; Shuto S.; Ono Y. Resolvin E1, but not resolvins E2 and E3, promotes fMLF-induced ROS generation in human neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2706–2715. 10.1002/1873-3468.13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalli J.; Chiang N.; Serhan C. N. Elucidation of novel 13-series resolvins that increase with atorvastatin and clear infections. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1071–1075. 10.1038/nm.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan C. N.; Petasis N. A. Resolvins and protectins in inflamma-tion resolution. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5922–5943. 10.1021/cr100396c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt D. A.; Tallman K. A.; Porter N. A. Free radical oxidation of polyunsaturated lipids: new mechanistic insights and the development of peroxyl radical clocks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 458–467. 10.1021/ar200024c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H.; Xu L.; Porter N. A. Free radical lipid peroxidation: mechanisms and analysis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5944–5972. 10.1021/cr200084z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H.; Muromoto R.; Takakura Y.; Ishimura K.; Kanada R.; Fushihara D.; Tanabe M.; Matsubara K.; Hirao T.; Hirashima K.; Abe H.; Arisawa M.; Matsuda T.; Shuto S. Design and synthesis of cyclopropane congeners of resolvin E2, an endogenous proresolving lipid mediator, as its stable equivalents. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6224–6227. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-P.; Tjonahen E.; Keledjian R.; Zhu M.; Yang R.; Recchiuti A.; Pillai P. S.; Petasis N. A.; Serhan C. N. Anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving properties of benzo-lipoxin A4 analogs. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids 2009, 81, 357–366. 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr S. K.; Colas R. A.; Dalli J.; Chiang N.; Serhan C. N. Proresolving actions of a new resolvin D1 analog mimetic qualifies as an immunoresolvent. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, L904–L911. 10.1152/ajplung.00370.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stable conformations were calculated by a Monte Carlo conformational search using MacroModel 10.9 (Schrödinger, Inc.) with OPLS_2005 as a force field and H2O as a solvent condition.

- Stable conformations of m-BZ-RvE2 by calculations; see the Supporting Information.

- Calculations showed that p-BZ-RvE2 does not mimic any of the four stable conformers of RvE2.

- Ostwald R.; Chavant P. Y.; Stadtmüller H.; Knochel P. Catalytic asymmetric addition of polyfunctional dialkylzincs to β-stannylated and β-silylated unsaturated aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 4143–4153. 10.1021/jo00094a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Götz K.; Liermann J. C.; Thines E.; Anke H.; Opatz T. Structure elucidation of hypocreolide A by enantioselective total synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 2123–2130. 10.1039/c001794a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish A.; Lang A.; Kim T.; Chong J. M. The use of phosphine ligands to control the regiochemistry of Pd-catalyzed hydrostannations of 1-alkynes: synthesis of (E)-1-tributylstannyl-1-alkenes. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 861–864. 10.1021/ol702982x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmi E.; Abarbri M.; Duchêne A.; Langle-Lamandé S.; Thibonnet J. Efficient synthesis of substituted styrenes and biaryls (or heteroaryls) with regioselective reactions of ortho-, meta-, and para-bromobenzyl bromide. Synthesis 2012, 44, 2023–2040. 10.1055/s-0031-1290987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Białecka A.; Mak M.; Biedroń R.; Bobek M.; Kasprowicz A.; Marcinkiewicz J. S. Different pro-inflammatory and immunogenic potentials of Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis: implications for chronic inflammatory acne. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 2005, 53, 79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananias R. Z.; Rodrigues E. G.; Braga E. G.; Squaiella C. C.; Mussalem J. S.; Longhini A. L.; Travassos L. R.; Longo-Maugéri I. M. Modulatory effect of killed Propionibacterium acnes and its purified soluble polysaccharide on peritoneal exudate cells from C57B1/6 mice: major NKT cell recruitment and increased cytotoxicity. Scand. J. Immunol. 2007, 65, 538–548. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Both of α- and β-CP-RvE2s showed anti-inflammatory activity almost the same as that of RvE2 in the mouse model of bacteria-induced peritonitis. Therefore, on the basis of the data in Figure 6, showing an anti-inflammatory activity of o-BZ-RvE2 more active than RvE2, o-BZ-RvE2 is also more active than CP-RvE2: See ref (15).

- We investigated metabolic stability of β-CP-RvE2 under the same conditions with human liver microsomes: Its half-life was about 3 h and was less metabolically stable than RvE2.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.