Abstract

Healthcare today requires extensive sharing and access to patient health information. The use of health information technology (health IT) exacerbates patients’ privacy concerns because it expands the availability of patient data to numerous members of the healthcare team. Patient concerns about the privacy of their data may be associated with nondisclosure of their information to providers. Patient trust in physicians, a multi-dimensional perception influenced by patient, physician, and situational factors, can facilitate disclosure and use of health IT. Previous work has done little to explore how specific dimensions of trust in physicians are related to patient information-sharing concerns or behavior. Using data from a nationally-representative survey, we show that patients with higher trust in provider confidentiality have significantly lower likelihood of reporting having ever withheld important health information and lower likelihood of thinking it is important to find out who has looked at their medical records. Patient trust in physician competence is related to higher likelihood of thinking it is important for health care providers to share information electronically This work sheds light on the importance of considering multiple dimensions of trust for patient behavior and attitudes related to their information sharing with health care providers.

Introduction

The delivery of healthcare today requires extensive sharing of and access to patient health information. The use of health information technology (IT) expands the availability of patient data to numerous healthcare providers throughout and between healthcare organizations. Since the widespread expansion of electronic health record (EHR) implementation following the distribution of incentives by the HITECH act, use of Internet-enabled applications for health (e.g., patient portals, mHealth apps) has increased steadily over the past decade. Use of health IT has yielded numerous positive benefits for patients, including increased access to data and improved efficiency1. However, such benefits come with increased concern about the potential for privacy breaches2,3. Indeed patient concerns about the privacy of their health information can impede their access to health care and hinder disclosure to providers4-7, creating incomplete medical records. Complete information sharing by patients with providers is necessary to ensure the quality and accuracy of data available in health information systems.

Patient trust in physicians, a multi-dimensional perception,8-10 can potentially remedy the issue. Patient trust in physicians is influenced by patient, physician, and situational factors, and can facilitate disclosure9 and use of health IT11. One dimension, in particular, seems to matter more than others for ameliorating privacy concerns6,12: trust in physician confidentiality. However, few quantitative studies of trust in physicians explore multiple dimensions and those that do have only single measures of each dimension, leaving critical gaps in knowledge about how trust may matter8-10.

Systematic disparities in patient trust in physicians also exist, though again the dimensions of trust matter differently for different groups. Some research finds that racial and ethnic minorities have lower levels of certain dimensions of trust in physicians13,14 and other research shows that patients with devalued health characteristics have lower trust in physician confidentiality specifically12. Similarly, disparities in use of health IT exist between racial groups and between those with stigmatized health conditions, suggesting the need to further investigate how different dimensions of trust may be related to patient attitudes and behavior related to information sharing.

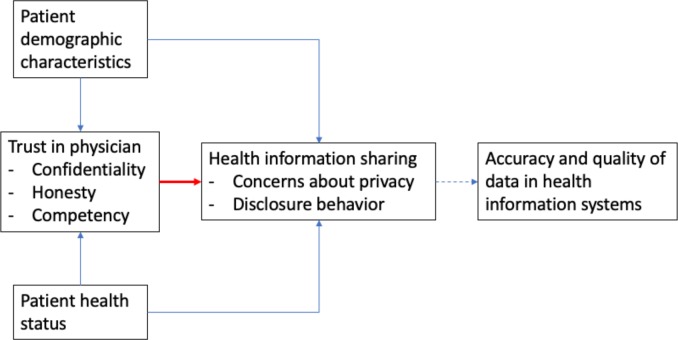

Here we analyze national survey data to determine how dimensions of patient trust in physicians are related to patient disclosure of health information and to attitudes about information sharing within health care (see Figure 1). Figure 1 situates our analysis in the context of existing work. Our analysis specifically focuses on the association between three dimensions of trust in physicians and patients’ attitudes towards privacy and health information disclosure behavior (represented by the red arrow in Figure 1). Associations between patient demographic characteristics, health status, trust in physician, and health information attitudes and behaviors are indicated by blue directional arrows. Finally, the association between accuracy and quality of data in health IT systems and health information attitudes and behaviors is represented by a dashed line, as this is an indirect consequence of patients’ disclosure behaviors and a needed focus of future work.

Figure 1.

Study Framework: Situating our Analysis

The red arrow represents the focus of our analysis.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, nationally-representative mail survey in 2014 to five thousand households across the United States based on three separate samples of households. For the general population sample, 1800 households were selected. For the Hispanic oversample, 1600 households were selected from the five communities with the highest concentration of Hispanics in the US: East Los Angeles, CA; Laredo, TX; Hialeah, FL; Brownsville, TX; and McAllen, TX. The African-American oversample included 1600 households from the following communities: Detroit, MI; Jackson, MS; Miami Gardens, FL; Birmingham, AL; and Baltimore, MD. In total, 5,000 households were selected. A total of 784 households completed the survey. The response rate of the survey was 15.7%. However, from the original sample of 5,000 households, 481 surveys were returned as undeliverable with no forwarding address available. The survey was conducted by the University of Nebraska Bureau of Sociological Research in partnership with Dartmouth College and was funded by HHS 90TR0003/01. Data weights account for sample design (including the three sampling frames), nonresponse, and population characteristics to be representative of the national population.

Respondents were asked whether they had ever withheld information from their provider because of privacy and security concerns (1=yes/0=no). Respondents were also asked two questions about attitudes towards privacy, namely, how strongly they agreed that it is important 1) to find out who has looked at their medical record and 2) that providers share their health information electronically (for each, strongly agree=1/less than strongly agree=0).

The survey also assessed several dimensions of trust in physicians9, based on previous literature: trust in physician confidentiality, trust in physician honesty, trust in physician competence, and overall trust in physician. Each dimension was measured with items using a 5-point Likert scale. Trust in physician confidentiality is an aggregate measure created as the average response to three statements, namely “I trust my doctor to keep personally sensitive information private15,” “I worry that private information my doctor has about me could be used against me15,” and “I worry that my doctor may share embarrassing information about me with people who have no business knowing it.16,17” Trust in physician honesty is an aggregate measure created as the average response to two statements, “I feel my doctor does not do everything s/he should for my medical care15” and “I trust my doctor to perform only medically necessary tests and procedures.18” Trust in physician competence is an aggregate measure created as the average response to three statements, “I trust my doctor to offer me high quality care18,” “my doctor is a real expert in taking care of medical problems like mine15,” and “my doctor’s medical skills are not as good as they could be” (reverse coded)16,17. An overall measure of complete trust is included as the response to the statement “all in all, I have complete trust in my doctor16,17,19.”

Data analysis was conducted using Stata 15.1. Survey data was analyzed using population sample weights. Logistic regression models were fitted to predict the three binary categorical dependent variables: having ever withheld information from providers due to concern about privacy, strongly agreeing that it is important that healthcare providers share my information electronically, and strongly agreeing that it is important that I can find out who has looked at my medical records. Independent variables are the four measures of trust: trust in confidentiality, honesty, competence, and overall trust. Each model controls for respondent demographic characteristics, self-rated health, health insurance status, and care quality (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of Consumer Characteristics, Analytic Sample N=542, unweighted

| Variables | % |

| Female | 51.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity African American, non-Hispanic | 8.8 |

| Hispanic | 6.6 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 84.6 |

| Age | |

| 18 – 29 years of age | 8.7 |

| 30 – 39 years of age | 20.5 |

| 40 – 49 years of age | 21.9 |

| 50 – 59 years of age | 22.0 |

| 60+ years of age | 26.8 |

| Education | |

| High School or less | 15.9 |

| Some College | 26.1 |

| BA/BS College Degree | 35.7 |

| Graduate Degree | 22.3 |

| Excellent or Good Self-rated Health | 84.9 (0.02) |

| Has health insurance | 96.9 |

| Quality of Health Care in previous 12 months | |

| Poor | 1.6 |

| Fair | 5.6 |

| Good | 32.2 |

| Very Good | 42.2 |

| Excellent | 18.3 |

Source: 2014 nationally-representative survey of US Adults. Author’s compilation

Results

Table 1 provides unweighted demographic details about the study sample. The majority of respondents in the sample are white (84.6%), educated with at least a BA/BS degree (58%), have excellent or good self-rated health (84.9%), have health insurance (96.0%), and report receiving very good or excellent health care in the previous year (60.5%).

We observe a significant association between trust in confidentiality and whether patients had ever withheld information from their doctor (OR = 0.20, Table 2). However, no significant associations were found between trust in provider honesty and competence and having ever withheld information. In a model predicting patients’ expectation that it is very important that providers share their health information electronically, we find a significant association with trust in physician competence (OR = 2.87), but no significant relationship with trust in physician confidentiality or honesty. Finally, in a model predicting patients’ expectation that it is very important that they find out who has looked at their medical records, we find a significant association with trust in physician confidentiality (OR = 0.59), but no significant association with trust in physician honesty or competence. No model showed a significant association between overall trust and the three dependent variables. All models control for race, gender, education, and age.

Table 2.

Odd-ratios for Logistic Regression of Trust in Physician dimensions on Patient Behavior and Expectations about Information Access and Sharing, Odds-ratios [95% CI]

| Ever Withheld Information because concerned about privacy | Very important that HC providers share my information electronically | Very important that I find out who has looked at my medical records | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Trust in physician | ||||||

| 0.60 | 0.45 | 1.94 * | 0.94 | 0.92 | 1.63 | |

| Overall | [0.32 – 1.1] | [0.15 - 1.4] | [1.2 – 32] | [0.43 - 2.0] | [0.61 – 1.4] | [0.86 - 3.1] |

| Honesty | 2.45 | 1.31 | 0.99 | |||

| [0.78 - 7.7] | [0.69 - 2.5] | [0.61 - 1.6] | ||||

| Competence | 3.53 | 2.87 * | 0.97 | |||

| [0.77 - 16.2] | [1.1 - 7.8] | [0.48 - 1.9] | ||||

| Confidentiality | 0.20 *** | 1.01 | 0.59 * | |||

| [0.10 - 0.42] | [0.48 - 2.2] | [0.35 - 0.99] | ||||

| With Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F-test | 3.9 *** | 3.3 *** | 4.6 *** | 4.0 *** | 1.6 | 2.6 *** |

| Degrees of freedom | 14,700 | 17,697 | 14,700 | 17,697 | 14,700 | 17,697 |

Source: 2014 nationally-representative survey of US Adults. Author’s compilation.

Discussion

Trust is an important determinant of patients’ behaviors and experiences of healthcare9,10,12,13, and here we show how it is associated with information sharing. We provide evidence that specific dimensions of trust in physicians, namely, trust in confidentiality and competency of providers, influence patients’ behaviors and expectations for information sharing in health care. This is in contrast to much previous work which considers trust to be a singular, generalized determinant of patient behavior. We find that specific dimensions of patient trust in physicians have unique associations, namely, trust in confidentiality is associated with lower odds of having ever withheld info and reporting concern about who is accessing their health record information. In addition, patients with higher levels of trust in physician competency have greater odds of agreeing that it is important for providers to share health information with each other. Encouraging patients’ health information sharing, and reducing patients’ withholding, may increase the accuracy and quality of health data available in health IT systems.

This work demonstrates not only that trust in providers is essential for information sharing, but that different dimensions of trust matter differently. This finding further supports previous work showing trust is situational12. Patients’ trust is not a singular, generalized phenomenon, instead it is a nuanced series of relationships based on specific expectations and behaviors. Moreover, we show that the individual dimensions of trust are particularly important to study, as each contributes in different ways to the patient experience and the physician-patient relationship.

Additionally, patient information disclosure and concerns about access are also multifaceted and nuanced. Patients are concerned about who accesses health data and why the data are used20. Perceptions of how data are used may also influence patients’ trust20. Trust in providers is associated with the quality of the doctor-patient relationship. Subsequently, dimensions of trust may play different roles in ensuring good communication between patients and providers, in patients’ use of healthcare services, and for adhering to treatment21,22.

Given systematic disparities in patient trust, in which racial and ethnic minorities have lower trust in physicians13,14, while patients with devalued health characteristics have lower trust in physician confidentiality than others12, further research is needed to examine how these factors may intersect with the dimensions of trust and their relationships to health information disclosure and concerns as shown here. This paper controls for patient age, gender, race, ethnicity, self-rated health, insurance status, and quality of health care but further study is needed to disentangle the relationships and possible interactions between and among them, dimensions of trust and health information sharing. Further, we have little understanding of how features of health IT applications interact with dimensions of patient trust. Health IT application design may unintentionally diminish trust or exacerbate rather than reduce privacy concerns that hinder use of beneficial health IT

These critical gaps in knowledge mean practitioners are missing when some patients, particularly the most vulnerable, may be more likely to have incomplete or inaccurate health data. The consequences of incomplete data include less effective treatment, more potential medical errors, and possible bias in treatment due to lack of data-representation in decision-making algorithms. Similar to a lack of representation in clinical studies, when patients’ data is absent, practitioners risk not learning which patients may most benefit from precision health treatments.

This study has a number of limitations that must be considered. First, data for this analysis come from a cross- sectional sample collected in 2014. Expansions in health IT use since then, as well as the evolution of available technologies, may change patients’ experiences and perceptions of technology. Additionally, qualitative research would allow more in-depth understanding of how different dimensions of trust influence patients’ behaviors and expectations about physicians, health IT, and privacy.

Conclusion

New information technologies in health care have the potential to enhance care quality and access, yet the widespread information sharing enabled by them also create new risks and concerns. Patients concerned about privacy may be less likely to disclose health information to providers and may be concerned about how their information is being used and accessed within the health care system. While trust is known to be an important factor in health care delivery and doctor patient relationships, previous work has not shown how specific dimensions of trust in physicians contribute to patient information sharing behavior or concerns. Here we show that one particular dimension of trust, trust in provider confidentiality, is associated with patients’ withholding information from clinicians and concerns about who is accessing their records, while a different dimension, trust in physician competency, is associated with agreeing that providers should share information. This is an important contribution given the increasing reliance on databases of patient information to tailor the delivery of care.

Ensuring that new technologies and their benefits are available to all patients, especially the most vulnerable, is necessary to prevent health disparities from widening as new effective health information technologies come in to widespread use. What is needed is an understanding of how dimensions of patient trust matter for health IT use and endorsement, whether particular dimensions of trust alleviate privacy concerns, and how features of health IT influence patient privacy concerns or usage.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Appari A, Johnson ME, Anthony DL. Meaningful Use of Electronic Health Record Systems and Process Quality of Care: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis of U.S. Acute-Care Hospitals. Health Services Research. 2013;48:354–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal D. Launching hitech. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:382–385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0912825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Technology PsCoAoSa. Report to the President: Realizing the Full Potential of Health Information Technology to Improve Healthcare for Americans. The Path Forward, https://www.himss.org/report-president-realizing- full-potential-health-information-technology-improve-healthcare-americans (2010, accessed 13 March 2019)

- 4.Anthony DL, Campos-Castillo C. A looming digital divide? Group differences in the perceived importance of electronic health records. Information, Communication & Society. 2015;18:832–846. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos-Castillo C, Anthony DL. The double-edged sword of electronic health records: implications for patient disclosure. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;22:e130–e140. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos-Castillo C, Woodson BW, Theiss-Morse E, et al. Shockley E, Neal TMS, PytlikZillig LM, et al. Examining the Relationship Between Interpersonal and Institutional Trust in Political and Health Care Contexts In: :99–115. (eds) Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust: Towards Theoretical and Methodological Integration Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stablein T, Hall JL, Pervis C, et al. Negotiating stigma in health care: disclosure and the role of electronic health records. Health Sociology Review. 2015;24:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall MA, Dugan E, Balkrishnan R, et al. How disclosing HMO physician incentives affects trust. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:197–206. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:657–668. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peek ME, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn MT, et al. Patient Trust in Physicians and Shared Decision-Making Among African-Americans With Diabetes. Health Commun. 2013;28:616–623. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.710873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisekka V, Giboney JS. The Effectiveness of Health Care Information Technologies: Evaluation of Trust, Security Beliefs, and Privacy as Determinants of Health Care Outcomes. J Med Internet Res; 20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9014. Epub ahead of print 11 April 2018. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campos-Castillo C, Anthony D. Situated Trust in a Physician: Patient Health Characteristics and Trust in Physician Confidentiality. The Sociological Quarterly. 2019;0:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sewell AA. Disaggregating ethnoracial disparities in physician trust. Social Science Research. 2015;54:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepanikova I, Mollborn S, Cook KS, et al. Patients’ Race, Ethnicity, Language, and Trust in a Physician. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:390–405. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the Trust in Physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychological reports. 1990;67:1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall MA, Camacho F, Dugan E, et al. Trust in the Medical Profession: Conceptual and Measurement Issues. Health Services Research. 2002;37:1419–1439. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring Patients’ Trust in their Primary Care Providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59:293–318. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao AC, Green DC, Zaslavsky AM, et al. The relationship between method of physician payment and patient trust. Jama. 1998;280:1708–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyles CR, Sarkar U, Ralston JD, et al. Patient–provider communication and trust in relation to use of an online patient portal among diabetes patients: The Diabetes and Aging Study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013;20:1128–1131. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agaku IT, Adisa AO, Ayo-Yusuf OA, et al. Concern about security and privacy, and perceived control over collection and use of health information are related to withholding of health information from healthcare providers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:374–378. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee Y-Y, Lin JL. The effects of trust in physician on self-efficacy, adherence and diabetes outcomes. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1060–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon HS, Street Jr RL, Sharf BF, et al. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. Journal of clinical oncology. 2006;24:904–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]