Abstract

Because of increased electronic health record use, many organizations are hiring medical scribes as a way to alleviate provider burnout and increase clinical efficiency. The providers and scribes have unique relationships and thus, this study’s purpose was to examine the scribe-provider interaction/relationship through the perspectives of scribes, providers, and administrators utilizing qualitative research techniques. Participants included 81 clinicians (30 providers, 27 scribes, and 24 administrators) across five sites. Analysis of the scribe-provider interaction data generated six subthemes: characteristics of an ideal scribe, characteristics of a good provider, provider variability, quality of the scribe-provider relationship, negative side of the scribe-provider relationship, and evaluation and supervision of scribes. Future research should focus on additional facets of the scribe-provider relationship including optimal ergonomic considerations to allow for scribes and providers to work together harmoniously.

Introduction

The use of electronic health records (EHRs) in the United States has increased dramatically over the past decade due to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act1. Subsequent to the adoption of EHRs, unintended consequences like over-documentation2 have occurred due in large part to regulatory mandates of documentation and documentation system inefficiencies. One way that organizations address physician dissatisfaction associated with the EHR and documentation is by hiring medical scribes. Mishra, Kiang, and Grant define medical scribes as “paraprofessionals who transcribe clinic visit information into the EHRs in real time under physician supervision3(p1468).” Prior research has demonstrated that the use of medical scribes lowered the documentation time for physicians3 and increased the time and quality of provider and patient interactions3,4. According to one study, medical scribes also “reduce the [provider’s] burden of record keeping and order entry5(p277).” Despite the documented benefits, concerns have been identified such as functional creep of scribe duties and the stifling of further development of EHR usability6.

Few comprehensive studies have analyzed the interaction of providers and scribes within the context of the sociotechnical environment in which they operate. Yan and colleagues4 conducted a seminal study that used qualitative research methods to investigate the role of clinical scribes through the lenses of providers, scribes, and patients in primary care. They described three themes: documentation, patient care, and teamwork (the scribe-provider interaction). They found that from the documentation perspective, the scribes captured information in real time and increased the amount of perceived detail in the providers’ notes. From the patient perspective, the patients perceived that provider spent more time focused on them and less time focused on the EHR by utilizing a medical scribe. From the teamwork perspective, high levels of communication and trust were important characteristics for both scribes and providers. Scribes also valued providers who were willing to teach. While this study had interesting findings, it only investigated primary care settings.

Sattler and colleagues conducted a one-year qualitative longitudinal study investigating four primary care providers and two scribes at one family care practice to learn more about the scribe-provider workflow and relationship7. They sent out surveys to the providers after each day and ultimately generated 11 themes, “which were further categorized under four domains: clinical operations, joy of practice, quality of care, and patient experience7(p51).” Regarding clinical operations, it was revealed that scribes lowered the amount of time providers spent writing notes. Surrounding the joy of practice, one physician said it was, “So fun to have a ‘partner in crime’ and to spend the day together7(p52)!” Another provider said that, “It’s also important to note that it is really fun having [the scribe] to work with. She is a friend now and a colleague7(p52).” In relation to quality of care, the study demonstrated that the scribes learned provider preferences and included more details than the providers did in their notes. The results surrounding patient experience revealed that the providers were able to spend more quality time with their patients and notice nonverbal communication they could have missed without the scribe in the exam rooms. The study had important limitations, including that it only investigated a single primary care clinic, had a small sample size (four providers and two scribes) and did not survey scribes.

Neither of these previously mentioned studies used a sociotechnical model as a framework for studying medical scribes. One of the more popular sociotechnical models is the eight dimensions of sociotechnical model for health information technology8. This model shows how all eight dimensions work together to help understand complicated healthcare entities.

The goal of the overall study was to use a sociotechnical model as a framework for studying scribes and the EHR in urgent care, emergency departments, and primary care settings across five organizations. The primary goal of the present study was to further expand knowledge of scribe-provider interactions and describe this relationship dynamic in-depth by analyzing what we discovered through interviews and observations from providers, scribes, and administrators. The overall purpose of this work was to investigate the climate of medical scribes in various practice settings and use this information to develop a set of simulation activities based on identified and needed competencies.

Methods

Settings: We used purposive sampling and selected our sites based on (a) the diversity of geographical location (b) size of clinics/hospitals, (c) whether the hospital/clinic was academic or community based, (d) EHR vendor, and (e) whether the scribes were hired through an internal program or a scribe company.

From October 2017 through January 2019, we conducted five site visits across the United States to hospitals and clinics in multiple geographic settings. The sites included teaching hospitals, community health systems, and outpatient clinics representing a wide range of sizes. Most clinics/hospitals were using the Epic system. However, one had recently switched from Cerner to Epic and one used AllScripts. We were interested in studying various scribing models; therefore, we visited one site that used virtual medical assistants (MAs) and nurses as medical scribes. Two of our sites used a traditional third party scribe company to hire scribes, which entailed hiring pre-professional scribes that were typically pre-health students. One of our sites had a homegrown scribe program where the hospital created their own pre-professional scribe company to hire and train scribes; the scribes were typically pre-health students. One of our sites used a scribe company that was closely tied to the academic hospital to hire pre-professional scribes; these scribes were typically college students with pre-health backgrounds.

Data gathering: We used the Rapid Assessment Process (RAP) model to construct our methodology9,10. RAP uses a rapid qualitative and ethnographic approach to aggregate and process data in a timely manner9,10. RAP helps establish ethnographic validity by using triangulation11. Triangulation is “the use of several different researchers, the use of multiple perspectives to interpret a single set of data, and the use of multiple methods to study a single problem11(p19).” During the site visits we triangulated by using different researchers and methodologies.

We used qualitative research methods including observations in the hospitals/clinics to collect our data where researchers created field notes which are “usually handwritten notes that are done as the data is being collected11(p54).” We also used semi-structured audio-recorded interviews, which allowed the participants to answer questions on our interview guide, but they could also expand on topics or discuss ideas that were not mentioned in the interview guide. The team included ten researchers with multidisciplinary backgrounds including clinical, informatics, scribe vendor industry, and methodological expertise. Two trained researchers worked in pairs conducting the interviews. One person was the lead interviewer ensuring all questions on the interview guide were answered while the assistant interviewer asked follow up questions and made sure that the recorders were functioning properly.

To gather a holistic view, we took a sociotechnical approach to study medical scribes based on the eight dimensions of sociotechnical model for health information technology8. During interviews and observations, we looked at the (a) hardware and software computing infrastructure, (b) clinical content, (c) human computer interface, (d) people, (e) workflow and communication, (f) internal organizational policies, procedures, and culture, (g) external rules regulation, and pressures, and (h) system measurement and monitoring. We used the eight dimensions of sociotechnical model for health information technology to study medical scribes. We investigated hardware and software computing infrastructure during our observations where we watched providers and scribes interact with the EHR. Through observations and interviews, we learned more about clinical content by hearing what vocabulary the scribes could add to the note. We observed human computer interface by watching the scribes interact with the EHRs. For people, we interviewed them and learned how the EHR made them feel and what kind of training they were provided to learn how to navigate the EHR. For workflow and communication, it was pertinent that we observed the scribes’ workflow and see how they communicate with their providers. For a couple of the site visits, we were able to look at different organizations’ policies and procedures when it came to what scribes can and cannot do during a patient visit. It was pertinent that we investigated external rules, regulations, and pressures as well; we did by looking at the Joint Commission’s policies on medical scribing. Lastly, we looked at system measurements and monitoring through interviews and observations; we would ask how the scribes were monitored; all the organizations handled monitoring differently. We gathered data until we reached saturation, meaning until we were seeing and hearing the same things repeatedly.

Analysis: Using NVivo 11, we coded our transcriptions and iteratively conducted a theme analysis using a grounded theory approach. We began our coding process by using a dyad system to conduct a line by line analysis of the field notes and transcripts to identify repeated concepts, which we turned into codes. Once we created the codebook, we were able to use that to code our field notes and transcripts. Most of the transcripts and field notes were coded using dyad pairs consisting of the research team members who all had different backgrounds and allowed for a multidisciplinary approach. The team met often to discuss results and report findings, which is a form of member checking and helps validate the results. We used the codes we found in the transcripts and field notes to develop the themes and subthemes. Overall, we had ten coders who helped code the transcripts and field notes.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Oregon Health & Science University. IRB review and/or official determinations (if a site did not have an IRB, it had other mechanisms for reviewing our protocol) were also obtained from all sites.

Results

We visited five site visits across the United States with varying differences (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Site visit demographics.

| Site A | Site Β | Site C | Site D | Site E | Total | |

| Geographie location | Northwest | Northwest | East | Midwest | Northwest | 5 sites |

| Characteristics of setting | Teething Hospital and Clinics | Community Health Systems | ENT Clink | Teaching Hospitals and EDs | Urgent Care and ENT Clinics | |

| Dates of Site Visits | Oct 2017-Jan 201S | Jan-Feb 2018 | Aug 2018 | Oct 2018 | Dec 2018-Jan 2019 | Oct 2017 Jan 2019 |

| EHR Used | Commercial (EPIC) | Commercial (EPIC) | Commercial (AllScripts) | Commercial (EPIC) | Commercial (EPIC) | 4 Commercial (EPIC) 1 Commercial (AllScripts) |

| Total Hours Interviewed (hours) | 12 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 47 hours |

| Total number of interviews | 13 interviews 14 people 4 providers 4 scribes 6 administrators |

15 interviews 18 people 6 providers 5 scribes 7 administrators |

18 interviews 18 people 8 providers 6 scribes 4 administrators |

19 interviews 19 people 6 providers 7 scribes 6 administrators |

11 interviews 12 people 6 providers 5 scribes 1 administrator |

76 interviews 81 people 30 providers 27 scribes 24 administrators |

| Number of clinics observed | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 12 Clinics |

| Total number of people observed | 5 people 2 scribe/provider dyads 1 provider (no scribe) |

12 people 6 scribe/provider dyads |

8 people 4 scribe/provider dyads |

16 people 8 scribe /provider dyads |

11 people 5 scribe/provider dyads 1 provider (no scribe) |

52 people 25 scribe/provider dyads 2 providers (no scribes) |

| Total number of hours observed | 17 hours | 20 hours | 6 hours | 25 hours | 12 hours | 80 hours |

During our site visits, we interviewed a total of 81 clinicians (30 providers, 27 scribes, and 24 administrators) for a total of 47 hours of recorded audio. Physician interviews ranged from 9 minutes to 58 minutes; scribe interviews ranged from 11 minutes to 65 minutes; administrator interviews ranged from 21 minutes to 80 minutes. Most interviews took place in person, but one interview took place over the phone. It is important to note that nine of our interviews had only one interviewer instead of two due to members of the research team needing to be in other interviews or observing.

We observed at five sites, which included 12 clinics. Specifically, there were two Urgent Care Clinics, two Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Clinics, three Family Medicine Clinics, three Emergency Departments (EDs), one Pediatric Cardiology Department, and one Sports Medicine Department. We spent a total of 80 hours observing.

Through this research we discovered ten majors themes (see Figure 1)12.

Figure 1.

Themes of sociotechnical research on medical scribes.

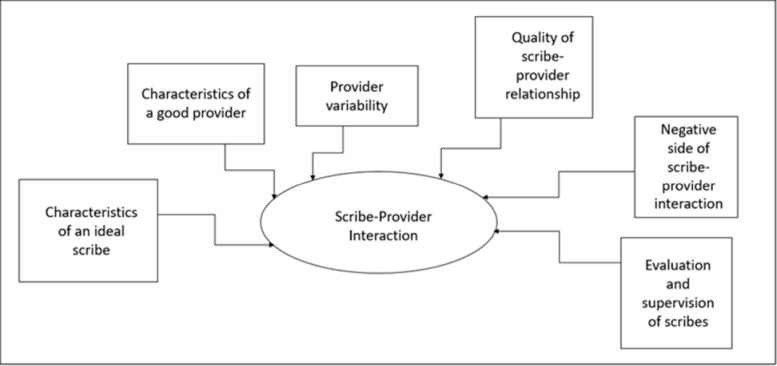

We have previously described ten themes emanating directly from our data12, but this paper will focus on the scribeprovider interaction theme. The scribe-provider interaction theme is crucial in explaining how the provider and scribe work together effectively and how their relationship could improve. Through qualitative analysis, we found that this general theme included six subthemes: characteristics of an ideal scribe (knowledge/characteristics all exceptional scribes should possess), characteristics of a good provider (knowledge/characteristics all exceptional providers/scribeusers should possess), provider variability (how providers differ and the impact these differences have on scribes), quality of relationship (the benefits of the scribe and provider relationship), negative relationship (the negative aspects of the scribe and provider relationship), and evaluation and supervision of the scribes (what level of evaluation/supervision the scribes receive from the providers) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Subthemes of the scribe-provider interaction theme.

Characteristics of an Ideal Scribe

During the interviews and observations, scribes, providers, and administrators offered descriptions of characteristics they felt scribes should exhibit and key knowledge a scribe should possess. One of the most commonly occurring characteristics was excellent communication. An ideal scribe can communicate openly with the provider and “ask a few questions” to clarify things. One scribe said that, “The more communication you have with your provider… the better it is for everyone.” The same scribe further went on to state that scribes are, “in a healthcare system and communication is the only way to get things done right. You can’t expect people just to read your mind.” With the unique dynamic between a provider and the scribe, the scribes need to be willing to communicate their needs. As a provider explained, “one of the hallmarks of a great scribe too is speaking up for yourself. We are moving so fast in clinic that I feel like a good scribe will [ask questions or]…stop me so they can fill in the note.” Scribes also need to be able to handle criticism and feedback too. As one scribe stated, “Your provider is going to give you criticisms, and we talk about ways to kind of turn that into a positive rather than negative.”

It is important for scribes to be flexible/adaptable as well. Many of the scribes we interviewed and observed worked with multiple providers and in multiple clinics/specialties; they had to adapt quickly to the provider’s preferences and department differences. One administrator said that scribes “aren’t the one that’s leading the pace or direction of this investigation. [They] are along for the ride and sort of adjusting the entire time.” Because they have to adapt to situations quickly, being able to handle pressure is critical. In reference to one urgent care clinic, a scribe stated that, “getting flustered, easily, isn’t going to work well in this atmosphere.”

An ideal scribe should have some sort of medical/healthcare background (e.g., current pre-medical student, prior work as another healthcare professional [MA, CNA]). Due to the fast-paced environment of scribing, knowledge of medical terminology (including anatomy and physiology) was mentioned multiple times as something scribes need to know well. Otherwise, a scribe might be inefficient if they struggle with terminology.

Professionalism, not only in appearance, but also in interactions towards patients and providers is key for scribes to be successful. As one scribe mentioned, a scribe needs to be “a fly on the wall, because [patients] are going through hard things and it’s hard enough to talk about [it] to one person, let alone one person and their helper in the corner… so just being respectful.” A provider told us she “wanted the scribe to be a fly on the wall, to melt into the corner, to not be a part of the conversation, to be an observer.” One site uses remote scribes to achieve this idea of “fly on the wall.” The scribes talk to the providers through audio only, with no video recording, which allows for the patients and providers to talk freely without the scribe physically present.

Scribes need to be able to type quickly with accurate spelling and grammar, and possess strong technology/computer skills (e.g., knowing how to navigate EHR). Scribes have been called the provider’s, “peripheral brain” because, “The scribe is [their] go-between the medical information being recorded and the scribe is also interacting with the [provider in] a way so [they] can interact with the patient in the best way possible.”

A scribe needs to be intelligent and a “quick learner.” One provider mentioned that pre-professional scribes “are just sponges, and they are so smart and so good at learning.”

Lastly, scribes, especially pre-professional scribes, must have a passion for medicine. As one scribe noted, scribes need to “be interested in medicine… that doesn’t mean being pre-med or pre-PA or whatever it may be, just having a genuine interest in learning everything about medicine.” A few people we interviewed and observed stated that having a passion for medicine ties in to motivation. One provider said, “I think a scribe who didn’t have an interest in medicine, I think, for obvious reasons, wouldn’t be motivated to learn the [medical] lingo necessarily.”

One scribe told us that her “motivation and interest in one day being a doctor” helps her be a great scribe. Another scribe said that the most important thing about being a scribe is that “you need to be motivated and actually enjoy medicine.” This scribe further went on to say that when he became a scribe he told himself that he wanted to become a PA “so everything that [he] was learning [he] was retaining.”

Characteristics of a Good Provider

Scribes, providers, and administrators often listed characteristics they felt providers/scribe users should have. Like an ideal scribe, a good provider is able to communicate effectively. One scribe mentioned that, “The more that a physician’s willing to communicate, the more smoothly that the day goes.” Another scribe noted, “It can get a little frustrating when they’re not communicating with you, or when they’re just doing their thing, and they pretend you’re not there.”

The scribes also want to work with providers who are willing to clarify exam findings and are clear about what they want in their note. One administrator told us that “the scribe’s role is purely… to do documentation under explicit direction and so an ideal provider is someone who realizes this and is very vocal and is able to think out loud.” A few scribes mentioned that they like it when a provider says the exam findings aloud during the exam, which allows them to be more efficient with their notes.

Staying organized is another key characteristic of a good provider; a scribe said that if the providers “are disorganized… it puts [them] behind because [they] cannot obtain the information that [the scribe] need[s] from them.”

One administrator said scribes “grow based on their feedback” from physicians, so scribes also want a provider who is willing to provide them with feedback, even if it is negative, so they can improve.

One of the most reoccurring characteristics of a good scribe user is one who is willing to teach. When talking about trying to find providers to use scribes, one administrator said that they “look for that doctor that has that teaching heart.” During an observation, one researcher noted that one provider was a “natural teacher, so he love[d] answering [the scribe’s questions] and explaining medicine to [the scribe].” A scribe stated that he thought the providers “[knew] scribing [was] not always the most exciting job. And so they [did] their best to help make it educational for [the scribes] and make it a good experience.”

Another scribe said that “being willing to teach your scribe [is important]. Like, we can only learn so much on our own. We can do all this research at home; but if you talk us through things, we’re not going to forget it, you know, when we’re seeing the flu or strep throat. And, you’re like, okay, this is what’s going to be. This is how we’re going to treat this. These are the generic symptoms for this. If they take the time, I feel like they put out what they put in. So, if they want to be our teacher, they’re going to get better charts out of it.”

A good provider must be willing “to give up a certain amount of control” when it comes to specific word usage in a note. One administrator said that, “A lot of [the providers] have a hard time [letting go of control of the note] and they need every word to be literally what they would have written.” They need to be able to “be comfortable with some degree of variation in the phrasing” of sentences.

One provider said that “some [providers he] knows are so meticulous and so detail oriented that everything has to be perfect… [he] thinks that people have to be flexible” when it comes to the note. The providers must review the scribes’ notes, but letting go of small structural changes or latitude changes in phraseology could allow the providers to review charts quickly.

Finally, a provider must have patience “because sometimes [the providers] forget that it is a human working the computer” and because “not every scribe is perfect on their first shift.” Scribes are an investment; as one provider said, “the more we invest in them the faster they learn and the better they get. So, it’s really on us to improve them.”

Provider Variability

Each provider is unique. As one researcher noted during observations, “the scribes usually said there were a variety of personalities and some were easier to deal with than others, but they like the variety.” This was the case for most of the sites. At every site, we observed that scribes had profiles that were specific to each provider and included provider preferences, templates, smart phrases/macros, general information on the specific clinical workflow, and common terminology. It is key for the scribes to be able to adapt to the provider’s variability.

One scribe summarized this: “Every provider is different and know[ing] the preferences before you walk in, you will have a better shift. If you walk in not knowing who you are working with or the preferences, I think it is going to be a rough shift… I have to come in maybe 15 minutes early and set up more macros than I would normally, or ask them more questions or be ready to type paragraphs on paragraphs on the HPI because they are so in-depth, versus other ones that are more laid back.” Maintaining profiles with provider preferences was especially useful for scribes who worked across specialties with multiple providers throughout any given week. Because providers have different preferences in their notes, a few sites have tried to improve this process as much as possible by creating a standardized note template for scribes to use across all providers.

Quality of Scribe-Provider Relationship

The scribe and provider have a unique relationship; as summarized by a scribe, “there are very few people in the clinic, if anybody, who spends as much time with the provider as the scribe does.” Because of the amount of time spent together, setting up a functional relationship between the scribe and provider is critical. The providers want to be “able to bond with [their] scribes” and the scribes want that relationship too. The scribe and provider must have a good rapport and work together as a team, despite the power dynamic. An administrator stated, “of course, there’s a hierarchy here but also, [the providers] are relying on [the scribes].” Another provider stated, “It is crucial to that relationship that the physician view the scribe as someone who’s a key member of the team.” As one provider noted, having a stronger overall relationship with his scribes led to a higher “quality of note that results as a consequence.”

Trust is a key component to this relationship dynamic as well. One administrator summarized, “if you don’t have that trust set up, you are [out of luck]. Because that is the foundation of scribing.” Typically, the longer a scribe is with a provider, the higher the level of trust can develop. Almost like a dating website, matching the scribes and providers is a key component to forming a high quality relationship. Scribe companies must determine what the provider’s personality is as well as the department’s culture, and try to find a scribe who will mesh well with the entire healthcare team. When the scribe-provider relationship is well formed, one provider noted that “we leave happy [at the end of the day]. We leave with a smile on [our] face.”

An administrator provided an example of how one scribe had been with the same provider for the past five years and the provider “loves her. She’s part of the family. [The provider] is not going to quit. He’s going to work forever”. If a solid relationship formed, the scribe can often predict the provider’s next move and anticipate what questions the provider will ask their patients. One provider told us that the scribes “are not transcriptionists at all… they’re pulling out things and dropping down things, and managing things, and gathering information from other sources for us. They’re doing stuff that I don’t feel competent to do. And I always tell them at the end of the day, thanks… we both do what we do best, and we, both complement each other.”

Negative Side of Scribe-Provider Relationship

While there are many positives to the scribe and provider relationship, during our site visits we also noted potential negative issues. One issue that was identified in multiple sites was the lack of provider revisions of scribed documentation prior to sign off.. One administrator stated that she “would guess a lot of the doctors, once they feel really comfortable with a scribe they do a quick review if they are being good [as in, being thorough]. But some of them may just sign and that’s where you get into the risk.” Another administrator mentioned that he “thinks that [providers] get kind of lax when they have had a scribe for a while… [and] read through [the note] but maybe just a lot quicker.”

A different administrator mentioned that she saw scribes “writing pretty junky notes… and the doctors were just signing them. Not reading, just sign, sign, sign, sign.” Another provider stated that “if I know my scribe is accurate almost all the time, then I can more quickly review the note and sign it off.” Most of the providers are aware of the importance of reviewing, though. As one provider stated, “it is our responsibility ultimately to edit that note.”

Despite efforts to match scribe and providers carefully, mismatches of clashing personalities sometimes occurred. For example, two administrators told us about a mismatch between the scribe and provider based on political preferences. One provider stated that, “Sometimes the scribe’s personality doesn’t work out and it does not mean they’re a bad scribe or there’s something done wrong.” Mismatches were also common because the provider and scribe had communication issues. One scribe talked about how they “rely on [the provider] to communicate… ‘cause if they’re not then it’s not gonna be a good work environment for either of [them].”

Departmental mismatches occurred as well. As one provider stated, “There’s some scribes that’ll come to us from another department where it’s an endocrinology visit and that person spends an hour-and-a-half with each individual patient and they see ten patients or whatever a day. That person has a hard time getting fast at Urgent Care type visits because you’re seeing people fast.” Mismatches also occurred because the providers lacked patience with their scribes who were new/inexperienced or slower. A few of the organizations try to alleviate mismatches between the scribe and provider by moving scribes to different departments that best match their personality and workflow.

The provider’s overreliance on scribes is another negative aspect that can lead to loss of productivity. Providers can become over-dependent on their scribes to write notes and navigate the EHR. Another provider mentioned the cognitive impact scribes have. He told us that “when he writes or types [the notes] himself, it goes into his brain and memory better. He finds himself asking the scribe to look things up that normally he would have remembered [if he had written the note himself].”

Another common negative was failing to make the scribe feel like part of the clinical team. Despite the efforts, the scribes sometimes felt like they were at the “bottom of the totem pole” when it came to working with the providers. While scribes are supposed to be part of the team with the provider, sometimes the providers asked the scribes to do tasks beyond their scope and the scribes complied. One administrator said that he has seen smaller clinics where “the providers are having the scribes log in as them and sign orders.”

Boundary issues may also occur. One administrator said that “scribes are bright, enthusiastic young people and they form personal relationships with the department and the physicians. Sometimes there are boundary issues with scribes.” This administrator said she has seen “things like scribes housesitting for [providers], scribes running errands for [providers], scribes doing nice things for doctors in expectation that will give them a better shot at a good letter [of recommendation].” With the power dynamic, it is the organization and provider’s responsibility to be clear and set boundaries.

Evaluation and Supervision of Scribes

An overarching theme we observed was the lack of standardization of evaluation and supervision of scribes. The evaluation and supervision of scribes seemed to vary not only between sites but also between individual providers within the same organization. A few of the scribe-provider pairs reviewed the notes after each patient, others reviewed notes together at the end of the day, and others providers reviewed the scribe’s notes on their own time away from the scribe. Each provider varied in the amount of feedback offered to the scribe. Occasionally providers offered regular feedback, which seemed to be valued by the scribes. However, not all providers offered much feedback. When this lack of feedback occurred, a couple of the scribes said that they learned to look back at past notes and see where changes were made, then they could adjust their notes in the future for that provider and learn from their mistakes. The scribes, however, do not have the clinical/medical background that the providers have to understand why these changes were made.

Trust plays a large role in the time providers spend evaluating scribes. As the provider’s trust increases, the amount of time reviewing notes and evaluating scribe performance decreases. One provider told us that “you see, you know, 25-30 patients and that, you know, three or four shifts a week, I can’t pore through everything. So, I pretty much trust my scribe on the history, the physical, the review of systems.” A scribe mentioned that “over time, providers start to trust you and know what you’re writing. And, obviously, I didn’t go to med school for 12 years, so I could have some errors in them, in my notes that I guess could be reviewed a little bit more in-depth… I guess the provider just kind of assumes that you know what you’re writing.”

The processes for scribe evaluation varied between study sites as well. Several of the sites had an informal process for evaluating a scribe’s performance. Typically, in these cases, the scribe management team would observe the scribe and offer remedial training if a provider had complained. The evaluation was more reactionary than proactive. Other sites had a more proactive approach to evaluating scribes. These sites had quarterly/monthly formal audits that took place where the scribe management team would audit a random selection of the scribes’ notes using specific grading criteria (e.g., did the chart get closed in a timely manner, did the scribe add their attestation). The scribe management team allowed the providers to “get a chance to evaluate the quality of scribe documentation as a part of the audit process.”

One of the scribes who audits the organization’s charts said that she “sends surveys to the providers each month, and [they’ll] rate them on… overall attitude, efficiency in charting, and so that’s their opportunity to… voice their concerns.” At the end of the quarter/month, the scribes would receive a document “about what [they] did right…[and] what [they] did wrong.” One scribe said that these monthly audits were “the way that most people learn.”

Discussion

This study is unique in its analysis of the scribe-provider interaction, and identification of components that make for a strong scribe and provider relationship. While there were overarching themes, we learned that there is great variability in what it takes for the scribe and provider to have a successful relationship. Every site did things in a slightly different way from the others; there was no observed standardization in how the scribe-provider interaction took place. Seeing the extent of variability between individual provider’s preferences and how organizations addressed this issue was fascinating. Some standardized providers’ notes as much as possible while other organizations asked scribes to keep track of different provider preferences.

This study found similar results to Yan and colleagues4; we saw that trust and communication are important characteristics for both scribes and providers. Furthermore, we also saw that providers need to be willing to teach their scribes and scribes need to have the necessary medical knowledge to write a note. The current study also expands on Yan and colleagues’ research. Their research specifically targeted primary care; we included urgent care and emergency departments as well as primary care in our study to show a more global picture of the scribe-provider interaction. We also observed the camaraderie between the providers and scribes noted in Sattler and colleagues’ research7. Their research focused on primary care providers, where are our study branched beyond primary care. They also had a small sample size that focused only on the physicians’ responses and we conducted interviews with 81 individuals (scribes, providers, and administrators).

The current study does have limitations. First, since we saw wide variation in scope and use of scribes in clinical practice during our site visit, we suspect that the results of this study cannot be generalized since we expect the degree of variability to be widespread in all areas of scribe use. Second, all of the sites we visited volunteered to participate in the study, which could skew data or allow for bias. It would be beneficial if future studies investigated what the best ergonomics are for making the scribe-provider interaction more efficient. Through observations, we noted that the layout of the exam rooms could sometimes hinder how well a scribe could document the patient-provider interaction and there is very little research on ergonomics in regards to the scribe-provider relationship. Finally, determining best practices for scribes and providers/scribe users is key for making the relationship function. Future research should determine the best practices necessary to optimize this domain.

Conclusion

If scribes are to efficiently and safely assist providers in generating documentation using the EHR, the relationship between scribe and provider pairs need to be a constructive one. The scribe and provider need to be matched well in order for this relationship to blossom. The providers must supervise and evaluate their scribes’ performance as well. It is just as important that providers learn to be good scribe users as it is that scribes learn to do their job well. Providers who use scribes need training about how to use scribes most effectively. An important aspect of using them effectively is to continuously and deliberately promote positive relationships with them.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by AHRQR01HS025141. We would like to thank Jeremy Liu, Renee Kostrba, Peter Lundeen, and Marcia Sparling for their help at each site as well as the administrators, providers, and scribes for their participation in this project.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Buntin MB, Burke MF, Hoaglin MC, Blumenthal D. The benefit of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Affairs. 2011;30(3):464–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Landman AB. Use of medical scribes to reduce documentation burden: are they where we need to go with clinical documentation? JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(11):1472–73. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra P, Kiang JC, Grant RW. Association of medical scribes in primary care with physician workflow and patient experience. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(11):1467–72. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan C, Rose S, Rothberg MB, Mercer MB, Goodman K, Misra-Hebert AD. Physician, scribe, and patient perspectives on clinical scribes in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2016;31(9):990–95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3719-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank A, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Annals of Family Medicine. 2013;11(3):272–78. doi: 10.1370/afm.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health records. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1315–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sattler A, Rydel T, Nguyen C, Lin S. One year of family physicians’ observations on working with medical scribes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):49–56. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sittig DF, Singh H. A new socio-technical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(Suppl 3):i68–i74. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMullen CK, Ash JS, Sittig DF, Bunce A, Guappone K, Dykstra R, Carpenter J, Richardson J, Wright A. Rapid assessment of clinical information systems in the healthcare setting: an efficient method for time- pressed evaluation. Method Inf Med. 2011;50(4):299–07. doi: 10.3414/ME10-01-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ash JS, Sittig DF, McMullen CK, Wright A, Bunce A, Mohan V, Cohen DJ, Middleton B. Multiple perspectives on clinical decision support: a qualitative study of fifteen clinical and vendor organizations. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2015:15–35. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beebe J. Rapid assessment process: an introduction. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ash JS, Gold JA, Mohan V, Bergstrom R, Becton J, Corby S. A sociotechnical multiple perspectives approach to the use of medical scribes: a qualitative study. Proceedings AMIA. 2018:1641–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]