Abstract

The pivotal role of viral proteases in virus replication has already been successfully exploited in several antiviral drug design campaigns. However, no efficient antivirals are currently available against flaviviral infections. In this study, we present lead-like small molecule inhibitors of the Zika Virus (ZIKV) NS2B-NS3 protease. Since only few nonpeptide competitive ligands are known, we take advantage of the high structural similarity with the West Nile Virus (WNV) NS2B-NS3 protease. A comparative modeling approach involving our in-house software PyRod was employed to systematically analyze the binding sites and develop molecular dynamics-based 3D pharmacophores for virtual screening. The identified compounds were biochemically characterized revealing low micromolar affinity for both ZIKV and WNV proteases. Their lead-like properties together with rationalized binding modes represent valuable starting points for future lead optimization. Since the NS2B-NS3 protease is highly conserved among flaviviruses, these compounds may also drive the development of pan-flaviviral antiviral drugs.

Keywords: Flavivirus, protease, inhibitors, PyRod, 3D pharmacophores, Dynophores

Flaviviruses cause millions of infections and thousands of fatalities annually.1 Despite a high medicinal need, no approved antiflaviviral treatment is currently available.2 Vaccines preventing infections with frequently prevalent viruses such as yellow fever virus,3 Japanese encephalitis virus,4 tick-borne encephalitis virus,5 or dengue virus6 are approved, but not against emerging species such as West Nile virus (WNV) or Zika virus (ZIKV).2,7 Due to the high conservation of all flaviviral nonstructural (NS) proteins,8 designing broad-spectrum antivirals is a viable strategy for the treatment of recently emerged species.

Flaviviruses encode for seven NS proteins,9 whose functions are only understood well for the NS2B-NS3 and NS5.10 The NS2B-NS3 protease complex is essential for the flaviviral replication cycle by processing the viral polyprotein into functional units of the virion. The nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) forms the catalytically active domain of the protease complex.11 NS2B acts as a cofactor for the protease domain, supporting substrate binding.12,13 NS2B-NS3 is a serine protease showing substrate specificity and catalytic triad (S135, H51, and D75, Figure 1) similar to trypsin.14 This enzyme recognizes dibasic peptide sequences with a cleavage site between an arginine or lysine and amino acids with small side chains (alanine or serine).14−17

Figure 1.

Comparison of ZIKVPro (top, PDB-ID: 5YOF(20)) and WNVPro (bottom, PDB-ID: 5IDK(30)) binding pockets. The key-residues are highlighted with black letters and numbers. Pink letters and numbers indicate protease-subpockets. Gray backbone, NS2B; green backbone, NS3. This figure was generated using UCSF Chimera 1.13.1.31

NS2B-NS3 represents a promising drug target, since blocking proteases in other virus species, e.g. human immunodeficiency virus18 or hepatitis C virus,19 leads to disruption of the replication cycle, which has already yielded several antiviral drugs. Despite high scientific efforts, only a few small molecule Zika virus protease (ZIKVPro) inhibitors20−28 have been reported to date. Several reported nonpeptide compounds targeting the active site of the protease show undesirable properties for lead optimization, such as instability in aqueous solution20 or high molecular weight21,28 (>500 Da). As random findings in high-throughput screening campaigns, most active small-molecular competitive inhibitors have poorly characterized binding modes,21 rendering further development even more challenging. Allosteric inhibitors may lead to fast resistance development.29 Hence, we strive for the development of drug-like NS2B-NS3 protease inhibitors targeting the substrate-binding site by combining in-silico design and biochemical experiments. Our novel, rationally discovered inhibitors with validated binding modes and low molecular weight represent promising starting points for future hit optimization.

Literature research revealed a lack of high-quality bioactivity data for ZIKVPro. Reported competitive ligands show either low potency, high molecular weight, or low stability in aqueous solutions.20,21,28 The substrate binding site of WNV protease (WNVPro) and ZIKVPro shows a sequence identity of 83% (Figure 1), and several nonpeptidomimetic ligands for WNVPro were reported with activity below 50 μM8 (Supporting Information Table S1). Hence, WNVPro was used as a starting point for the identification of novel drug-like ZIKVPro inhibitors.

Substrate binding sites of WNVPro and ZIKVPro only differ at three residue positions (Figure 1). The S1 and S2 subpockets (Schechter–Berger nomenclature32) are highly conserved in flaviviral species14 and accept lysine and arginine.14 S3 and S4 subpockets show sequence-variability and accept various residues. Both substrate binding sites are highly flexible,13 hydrophilic, and shallow,33 rendering the NS2B-NS3 protease a challenging target for drug discovery.

In order to address binding pocket flexibility of WNVPro, we employed our novel application PyRod.34 In this tool, the protein environment of water molecules is analyzed over the course of an MD simulation. Pharmacophoric binding site characteristics can subsequently be visualized with dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs, Figure 2A). Features outside the highly conserved S1 and S2 subpockets were removed, and dMIFs were used to prioritize features inside the binding pocket to generate a focused 3D pharmacophore model consisting of 16 independent features (B1, Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs) and (B) focused (B1) 3D-pharmacophore model obtained from WNVPro MD simulations and PyRod analysis. Pink letters and numbers indicate protease subpockets. Color code: yellow spheres and clouds, lipophilic contacts; purple rings and blue clouds, aromatic interactions; red arrows and clouds, hydrogen bond acceptors; purple stars and clouds, cationic interactions.

Identified cationic interactions exploit contacts in the S1 subpocket to D129 and in the S2 subpocket to D75 and H51, while aromatic interactions are present facing Y161 and H51 in the S1 and S2 subpockets, respectively. Hydrogen bond acceptors are preserved in the essential oxyanion hole (S135, T134, G133) and in the backbone-binding region (G153, Y161). Lipophilic contacts are placed in the conserved regions of the S1 subpocket in proximity to Y161 and Y150. The resulting focused pharmacophore was used for combinatorial model library generation with PyRod. Since the interaction with residue D129 of NS3 is crucial for substrate recognition,14−17 we decided that the cationic chemical feature detected by PyRod in the S1 subpocket (Figure 2B) should be present in each pharmacophore model to enhance the likelihood of finding an active inhibitor. All other pharmacophore features were systematically combined and merged with the cationic feature to generate 3D pharmacophores with three to six independent pharmacophore features. This procedure resulted in a combinatorial library of 3022 different 3D pharmacophore models. The final pharmacophore ensemble was retrospectively evaluated by screening a collection of 17 small molecular WNVPro inhibitors reported in the literature35−39 and 667 decoy molecules derived from the active ligands by the DUD-E server (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced).40

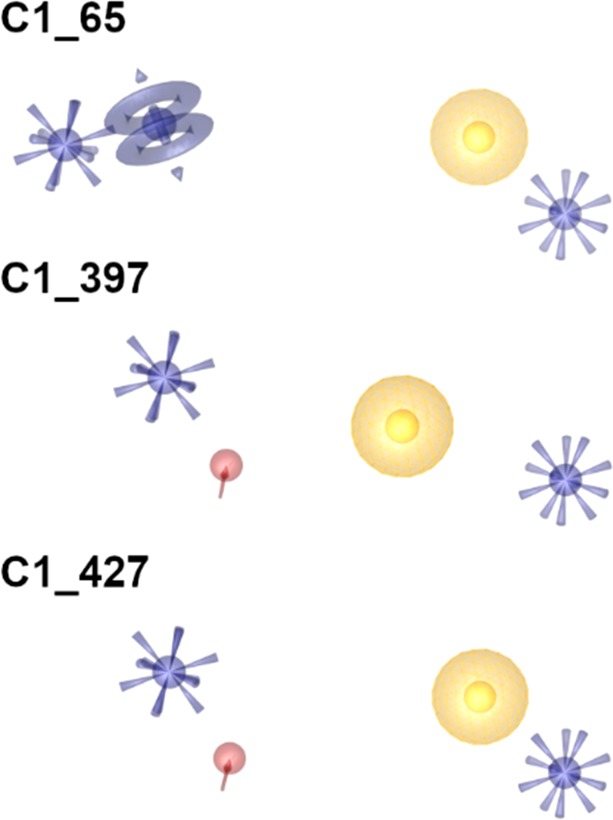

We compared the obtained early enrichment factors (EF1%) and absolute number of recovered active inhibitors for picking best performing pharmacophores (Supporting Information Figure S1). The three best performing models (C1_65, C1_397, and C1_427, Figure 3) were used for an extensive virtual screening (VS) campaign with more than 7.6 million commercially available compounds. In total 1079 virtual hits were detected (10 for C1_65, 712 for C1_397, and 357 for C1_427).

Figure 3.

Best performing pharmacophore models obtained from combinatorial model library (yellow spheres, lipophilic contacts; purple rings, aromatic interactions; red arrow, hydrogen bond acceptor; purple star, cationic interaction).

We docked obtained hits into the WNVPro substrate-binding pocket to explore plausible binding hypotheses. Subsequently, we minimized the energy of docking poses in the binding pocket using LigandScout41,42 and scored the ligand conformations based on their fit to the C1-pharmacophores (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Virtual screening protocol applied for screening of Zika and West Nile virus protease inhibitors.

All compounds were visually inspected to exclude unfavorable virtual hit orientations, such as lipophilic groups pointing toward the solvent, or nondrug like moieties43 (e.g. quinones) yielding 15 compounds. To ensure that the hits can bind to the highly flexible NS2B-NS3, we performed MD simulations with the best-scoring ligand conformations in complex with the protease. In total, five hits showed no conformational change in the binding pocket throughout 20 ns of MD simulation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Virtual hits selected for biochemical testing in the ZIKVPro and WNVPro assays. Pink letters and numbers indicate assumed arrangement of the compounds toward the protease-subpockets.

In the next step, we investigated if the five compounds obtained by WNVPro-modeling can also bind the ZIKVPro binding pocket. Therefore, we generated a focused 3D pharmacophore (B2) for the ZIKVPro applying PyRod, which was compared with the WNVPro pharmacophore B1. Both models showed analogous interaction patterns (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison between focused pharmacophores B1 (WNVPro based) and B2 (ZIKVPro based) obtained from PyRod analysis of MD simulations (yellow spheres, lipophilic contacts; purple rings, aromatic interactions; red arrow, hydrogen bond acceptor; purple star, cationic interaction).

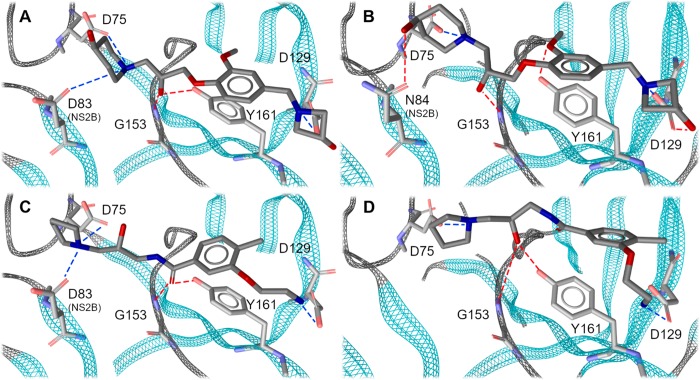

Moreover, the ZIKVPro structure exposes aspartic acid at position 83 (homologous to the N84 of WNVPro) in the NS2B part of the S2 subpocket (Figure 1). This polymorphism is proposed to be responsible for higher affinity of ZIKVPro toward the substrate allowing for salt-bridge formation to lysine or arginine.44 Due to pharmacophoric properties of selected compounds with conserved cationic interaction in the S2 subpocket, we suspected that the hits might be even better ZIKVPro than WNVPro inhibitors. After performing docking and MD simulations of the WNV-hits at ZIKVPro, we observed stable binding to the protein, which supported our hypothesis.

Finally, the five virtual screening hits were evaluated biochemically for inhibition of ZIKVPro and WNVPro. Five selected compounds were tested on ZIKVPro and WNVPro systems using fluorescence-based assays. Two ligands showed inhibition of both proteases below a 50 μM cutoff. For these compounds, Ki values were determined (Table 1, Supporting Information Figure S2).

Table 1. Inhibitory Activity of Selected Hits against ZIKV, WNV, and DENV2 Proteasea.

| Compound | ZIKVPro Ki [μM] | WNVPro Ki [μM] | DENV2Pro Ki [μM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 397_2 | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | n.d. |

| 397_6 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 397_12 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 427_1 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 25.5 ± 11.8 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| 427_2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Ki values were determined for the ligands with inhibition cutoff below 50 μM. n.d.: not determined.

Since molecular modeling was only performed on R-enantiomers found in the virtual screening campaign, but the protease assays were carried out with the commercially available racemic mixtures, we assume that the activity of enantiomer-pure compounds would be even higher. Positive testing results encouraged us additionally to evaluate the inhibitory activity of our compounds on closely related Dengue virus 2 (DENV2) protease (for details see Supporting Information). Compound 397_2 showed slightly lower inhibition in the ZIKVPro than WNVPro assay, however, as predicted in the same range. Compound 427_1 displayed the highest activity against ZIKVPro with an unexpected pronounced difference to WNVPro of one order of magnitude. We surmise that this effect is unrelated to the slightly different pH value in the two assays (see Supporting Information, page 5). In the next step we established binding hypotheses for the active inhibitors. The suggested binding mode of compound 397_2 is shown in Figure 7. Subsequently, we analyzed why compound 427_1 shows an order of magnitude affinity difference between WNVPro and ZIKVPro. To investigate this, we performed 50 ns MD simulations in five replicates and analyzed the trajectories with regard to the ligand–protein interactions using our in-house dynamic pharmacophore analysis method Dynophore.45,46 We observed recurring comparable interaction patterns indicating two distinct binding modes for the 427_1–ZIKVPro complex. The first binding mode is matching our PyRod pharmacophore C1_427 (Figure 7C, Figure 8A).

Figure 7.

Proposed binding modes for the active inhibitors; compound 397_2 in complex with ZIKVPro (A) and WNVPro (B); compound 427_1 in complex with ZIKVPro (C, according to the PyRod pharmacophore) and WNVPro (D). Color code: blue lines, ionic contacts; red lines, hydrogen bonds.

Figure 8.

Dynamic pharmacophores generated from MD simulations of compound 427_1; interaction patterns detected for 427_1–ZIKVPro complex (A: dynamic pharmacophore fulfilling the initial binding hypothesis obtained from PyRod, B: alternative binding mode supported by the ionic interaction with D83), (C) interaction patterns generated for 427_1–WNVPro complex (dynamic pharmacophore fulfilling the initial binding hypothesis obtained from PyRod). Color code: yellow points, lipophilic contacts; red and green points, hydrogen bond acceptors and donors, respectively; purple points, cationic interactions.

The second one shows preserved interactions in the S2 subpocket and additional features between the S3 and S4 subpockets (Figure 8B) introduced by a movement of the aminoethoxyphenyl moiety from the S1 subpocket toward D83 of NS2B. The ability to adapt two binding modes could represent an entropic gain resulting in a lower Ki value, even if the crucial S1 subpocket is not occupied. Moreover, frequent lipophilic contacts to V155 of the NS3 domain were detected, which potentially contributes to the entropic benefit of the second binding mode. The simulation-analysis of 427_1–WNVPro complex shows the same interaction pattern as for ZIKVPro (Figure 7D, Figure 8C).

According to the simulation, the second binding mode (dynamic pharmacophore not shown) is less stable and potentially leads to an unbinding event contributing to lower activity of compound 427_1 on the WNVPro. These findings correspond to the previously hypothesized importance of D83 for ligand binding to the ZIKVPro as indicated by X-ray crystal structures of peptidomimetic inhibitor–protease complexes.44,47 The visual inspection of simulation trajectories of 427_1–ZIKVPro complexes shows that the side chain of D83 can adapt two conformations: one pointing toward the S2 subpocket and another pointing toward the S3 subpocket. The alternative binding hypothesis might be used directly for the optimization of compound 427_1. Since WNVPro expresses an asparagine at position 84 of NS2B, including a cationic moiety pointing toward S3/S4 subpockets would not be beneficial, despite reported favorable ionic interaction with D90 in NS2B of WNVPro.48 The aminoethoxy-moiety of inhibitor 427_1 is too short to reach this protease region as shown for a variety of substrates by Chappell et al.49 An additional lipophilic moiety and a hydrogen bond donor (as replacement for the amino-moiety of ligand 427_1) could rather be introduced creating a T-shaped molecule preventing the ligand from flipping and preserving ionic interactions with crucial D129. We surmise that this ligand design might equalize the activity of inhibitors between WNVPro and ZIKVPro. We inspected the structures of all ligands tested biochemically to find a suitable descriptor discriminating between active and inactive structures. We put our focus on the flexibility of compounds described as number of rotatable bonds. We surmised that rigid structures cannot adapt to the highly flexible NS2B-NS3 protease. Indeed, the active inhibitors of ZIKVPro and WNVPro show more than seven rotatable bonds. This finding indicates that proteases prefer flexible ligands that can adjust to the binding pocket.

In this report, we present two novel, highly active, noncovalent and competitive inhibitors of WNV, ZIKV, and DENV2 proteases. To our knowledge, this is the first study performing a successful pharmacophore-based virtual screening campaign against these targets. The identification of the hits was possible by applying the novel software called PyRod. It enabled us to overcome challenging features of NS2B-NS3 substrate-binding pockets, such as high flexibility, hydrophilicity, and shallowness. The reported compounds represent good starting points for further optimization with established in silico binding hypothesis and their drug-like properties, such as low molecular weight and absence of reactive moieties. Moreover, the 3D pharmacophore properties and inhibitory activity of our hits on three different proteases suggest the possibility to develop pan-flaviviral NS2B-NS3 inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge MS Pharma, Biosupramol (Freie Universität Berlin) for providing us the analytical devices and Lukas Harps and Jan Joseph (Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, Institute of Pharmacy, Freie Universität Berlin) for the purity control of tested compounds. C.N. thanks the Australian Research Council for a Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE190100015).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DENV2

Dengue virus serotype 2

- EF1%

early enrichment factor

- MD

molecular dynamics

- NS

nonstructural protein

- VS

virtual screening

- WNV

West Nile virus

- WNVPro

West Nile virus protease

- ZIKV

Zika virus

- ZIKVPro

Zika virus protease

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00629.

Computational and experimental methods, and supplementary tables and figures (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.P. designed, conducted, and analyzed in-silico experiments. T.S. and C.N. performed and analyzed the ZIKV protease assay and R.Y. the WNV protease assay. C.A. established WNV and DENV2 protease expression and developed WNV and DENV2 assay. S.B. expressed the WNV protease and performed DENV2 protease assay. S.P., T.S., D.S., C.N., J.R., and G.W. wrote the manuscript. J.R., C.N., and G.W. supervised the studies. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Guzman M. G.; Harris E. Dengue. Lancet 2015, 385 (9966), 453–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60572-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnut M.; Munoz L. S.; Harris G.; Freeman D.; Gama L.; Pardo C. A.; Pamies D. In vitro and in silico Models to Study Mosquito-Borne Flavivirus Neuropathogenesis, Prevention, and Treatment. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 223. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler M.; Smith H. H. The Use of Yellow Fever Virus Modified by in Vitro Cultivation for Human Immunization. J. Exp. Med. 1937, 65 (6), 787–800. 10.1084/jem.65.6.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. K.; Putnak J. R.; Lee S. H.; Hong S. P.; Moon S. B.; Barvir D. A.; Zhao B.; Olson R. A.; Kim S.-O.; Yoo W.-D.; Towle A. C.; Vaughn D. W.; Innis B. L.; Eckels K. H. A purified inactivated Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine made in Vero cells. Vaccine 2001, 19 (31), 4557–4565. 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zent O.; Banzhoff A.; Hilbert A. K.; Meriste S.; Słuzewski W.; Wittermann C. Safety, immunogenicity and tolerability of a new pediatric tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) vaccine, free of protein-derived stabilizer. Vaccine 2003, 21 (25–26), 3584–3592. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy B.; Barrere B.; Malinowski C.; Saville M.; Teyssou R.; Lang J. From research to phase III: preclinical, industrial and clinical development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine 2011, 29 (42), 7229–41. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. H.; Metz S. W. Progress and Works in Progress: Update on Flavivirus Vaccine Development. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39 (8), 1519–1536. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldescu V.; Behnam M. A. M.; Vasilakis N.; Klein C. D. Broad-spectrum agents for flaviviral infections: dengue, Zika and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (8), 565–586. 10.1038/nrd.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds P.; Becher P.; Bukh J.; Gould E. A.; Meyers G.; Monath T.; Muerhoff S.; Pletnev A.; Rico-Hesse R.; Smith D. B.; Stapleton J. T.; Ictv Report C. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98 (1), 2–3. 10.1099/jgv.0.000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows N. J.; Campos R. K.; Liao K. C.; Prasanth K. R.; Soto-Acosta R.; Yeh S. C.; Schott-Lerner G.; Pompon J.; Sessions O. M.; Bradrick S. S.; Garcia-Blanco M. A. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Flaviviruses. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118 (8), 4448–4482. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assenberg R.; Mastrangelo E.; Walter T. S.; Verma A.; Milani M.; Owens R. J.; Stuart D. I.; Grimes J. M.; Mancini E. J. Crystal structure of a novel conformational state of the flavivirus NS3 protein: implications for polyprotein processing and viral replication. J. Virol. 2009, 83 (24), 12895–906. 10.1128/JVI.00942-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falgout B.; Pethel M.; Zhang Y. M.; Lai C. J. Both nonstructural proteins NS2B and NS3 are required for the proteolytic processing of dengue virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 1991, 65 (5), 2467–75. 10.1128/JVI.65.5.2467-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel P.; Schiering N.; D’Arcy A.; Renatus M.; Kroemer M.; Lim S. P.; Yin Z.; Keller T. H.; Vasudevan S. G.; Hommel U. Structural basis for the activation of flaviviral NS3 proteases from dengue and West Nile virus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006, 13 (4), 372–3. 10.1038/nsmb1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan J. F.; Fletterick R. J. Detection of a trypsin-like serine protease domain in flaviviruses and pestviruses. Virology 1989, 171 (2), 637–639. 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90639-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nall T. A.; Chappell K. J.; Stoermer M. J.; Fang N. X.; Tyndall J. D.; Young P. R.; Fairlie D. P. Enzymatic characterization and homology model of a catalytically active recombinant West Nile virus NS3 protease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (47), 48535–42. 10.1074/jbc.M406810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell K. J.; Nall T. A.; Stoermer M. J.; Fang N. X.; Tyndall J. D.; Fairlie D. P.; Young P. R. Site-directed mutagenesis and kinetic studies of the West Nile Virus NS3 protease identify key enzyme-substrate interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (4), 2896–903. 10.1074/jbc.M409931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Lim S. P.; Beer D.; Patel V.; Wen D.; Tumanut C.; Tully D. C.; Williams J. A.; Jiricek J.; Priestle J. P.; Harris J. L.; Vasudevan S. G. Functional profiling of recombinant NS3 proteases from all four serotypes of dengue virus using tetrapeptide and octapeptide substrate libraries. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (31), 28766–74. 10.1074/jbc.M500588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Osswald H. L.; Prato G. Recent Progress in the Development of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV/AIDS. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (11), 5172–208. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselah T.; Boyer N.; Saadoun D.; Martinot-Peignoux M.; Marcellin P. Direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: optimizing current IFN-free treatment and future perspectives. Liver Int. 2016, 36 (Suppl 1), 47–57. 10.1111/liv.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhang Z.; Phoo W. W.; Loh Y. R.; Li R.; Yang H. Y.; Jansson A. E.; Hill J.; Keller T. H.; Nacro K.; Luo D.; Kang C. Structural Insights into the Inhibition of Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease by a Small-Molecule Inhibitor. Structure 2018, 26 (4), 555–564. e3. 10.1016/j.str.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Ren J.; Nocadello S.; Rice A. J.; Ojeda I.; Light S.; Minasov G.; Vargas J.; Nagarathnam D.; Anderson W. F.; Johnson M. E. Identification of novel small molecule inhibitors against NS2B/NS3 serine protease from Zika virus. Antiviral Res. 2017, 139, 49–58. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y.; Huo T.; Lin Y. L.; Nie S.; Wu F.; Hua Y.; Wu J.; Kneubehl A. R.; Vogt M. B.; Rico-Hesse R.; Song Y. Discovery, X-ray Crystallography and Antiviral Activity of Allosteric Inhibitors of Flavivirus NS2B-NS3 Protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (17), 6832–6836. 10.1021/jacs.9b02505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassias G.; Zogali V.; Swarbrick C. M. D.; Ki Chan K. W.; Chan S. A.; Gwee C. P.; Wang S.; Kaplanai E.; Canko A.; Kiousis D.; Lescar J.; Luo D.; Matsoukas M. T.; Vasudevan S. G. Cell-active carbazole derivatives as inhibitors of the zika virus protease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 180, 536–545. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millies B.; von Hammerstein F.; Gellert A.; Hammerschmidt S.; Barthels F.; Goppel U.; Immerheiser M.; Elgner F.; Jung N.; Basic M.; Kersten C.; Kiefer W.; Bodem J.; Hildt E.; Windbergs M.; Hellmich U. A.; Schirmeister T. Proline-Based Allosteric Inhibitors of Zika and Dengue Virus NS2B/NS3 Proteases. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (24), 11359–11382. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher M.; Li Z.; Liu B.; Zhang J.; Koetzner C. A.; Alifarag A.; Jones S. A.; Lin Q.; Kramer L. D.; Li H. A conformational switch high-throughput screening assay and allosteric inhibition of the flavivirus NS2B-NS3 protease. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13 (5), e1006411 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev S. A.; Farhy C.; Pinto A.; Huang C. T.; Simonetti N.; Elong Ngono A.; Dewing A.; Shresta S.; Pinkerton A. B.; Cieplak P.; Strongin A. Y.; Terskikh A. V. Characterization of the Zika virus two-component NS2B-NS3 protease and structure-assisted identification of allosteric small-molecule antagonists. Antiviral Res. 2017, 143, 218–229. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A.; Lim L.; Srivastava S.; Lu Y.; Song J. Solution conformations of Zika NS2B-NS3pro and its inhibition by natural products from edible plants. PLoS One 2017, 12 (7), e0180632 10.1371/journal.pone.0180632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S.; Chan J. F.; den-Haan H.; Chik K. K.; Zhang A. J.; Chan C. C.; Poon V. K.; Yip C. C.; Mak W. W.; Zhu Z.; Zou Z.; Tee K. M.; Cai J. P.; Chan K. H.; de la Pena J.; Perez-Sanchez H.; Ceron-Carrasco J. P.; Yuen K. Y. Structure-based discovery of clinically approved drugs as Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease inhibitors that potently inhibit Zika virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 2017, 145, 33–43. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt Yilmaz N.; Swanstrom R.; Schiffer C. A. Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24 (7), 547–557. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C.; Zhang L.; Weigel L. F.; Schilz J.; Graf D.; Bartenschlager R.; Hilgenfeld R.; Klein C. D. Peptide-Boronic Acid Inhibitors of Flaviviral Proteases: Medicinal Chemistry and Structural Biology. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (1), 511–516. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25 (13), 1605–12. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A.; Schechter I. Mapping the active site of papain with the aid of peptide substrates and inhibitors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B. Biol. Sci. 1970, 257 (813), 249–64. 10.1098/rstb.1970.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Proteases from dengue, West Nile and Zika viruses as drug targets. Biophys. Rev. 2019, 11 (2), 157–165. 10.1007/s12551-019-00508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller D.; Pach S.; Wolber G. PyRod: Tracing Water Molecules in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59 (6), 2818–2829. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomiuk D.; Su X. C.; Ozawa K.; Bodenreider C.; Lim S. P.; Otting G.; Huang D.; Caflisch A. Flaviviral protease inhibitors identified by fragment-based library docking into a structure generated by molecular dynamics. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52 (15), 4860–8. 10.1021/jm900448m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomiuk D.; Su X. C.; Ozawa K.; Bodenreider C.; Lim S. P.; Yin Z.; Keller T. H.; Beer D.; Patel V.; Otting G.; Caflisch A.; Huang D. Discovery of a non-peptidic inhibitor of west nile virus NS3 protease by high-throughput docking. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2009, 3 (1), e356 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenreider C.; Beer D.; Keller T. H.; Sonntag S.; Wen D.; Yap L.; Yau Y. H.; Shochat S. G.; Huang D.; Zhou T.; Caflisch A.; Su X. C.; Ozawa K.; Otting G.; Vasudevan S. G.; Lescar J.; Lim S. P. A fluorescence quenching assay to discriminate between specific and nonspecific inhibitors of dengue virus protease. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 395 (2), 195–204. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh V. K.; Muller N.; Judge K.; Luan C. H.; Padmanabhan R.; Murthy K. H. Identification and characterization of nonsubstrate based inhibitors of the essential dengue and West Nile virus proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13 (1), 257–64. 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregar-Hernandez L.; Jiao G. S.; Johnson A. T.; Lehrer A. T.; Wong T. A.; Margosiak S. A. Small molecule pan-dengue and West Nile virus NS3 protease inhibitors. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2011, 21 (5), 209–17. 10.3851/IMP1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysinger M. M.; Carchia M.; Irwin J. J.; Shoichet B. K. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (14), 6582–94. 10.1021/jm300687e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolber G.; Dornhofer A. A.; Langer T. Efficient overlay of small organic molecules using 3D pharmacophores. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 20 (12), 773–88. 10.1007/s10822-006-9078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolber G.; Langer T. LigandScout: 3-D pharmacophores derived from protein-bound ligands and their use as virtual screening filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45 (1), 160–9. 10.1021/ci049885e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J. B.; Holloway G. A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53 (7), 2719–40. 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J.; Hansen G.; Nitsche C.; Klein C. D.; Zhang L.; Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of Zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease in complex with a boronate inhibitor. Science 2016, 353 (6298), 503–5. 10.1126/science.aag2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock A.; Bermudez M.; Krebs F.; Matera C.; Chirinda B.; Sydow D.; Dallanoce C.; Holzgrabe U.; De Amici M.; Lohse M. J.; Wolber G.; Mohr K. Ligand Binding Ensembles Determine Graded Agonist Efficacies at a G Protein-coupled Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291 (31), 16375–89. 10.1074/jbc.M116.735431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier J.; Prevost J. R. C.; Sydow D.; Teuchert S.; Omieczynski C.; Bermudez M.; Frederick R.; Wolber G. Arginase Structure and Inhibition: Catalytic Site Plasticity Reveals New Modulation Possibilities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 13616. 10.1038/s41598-017-13366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhang Z.; Phoo W. W.; Loh Y. R.; Wang W.; Liu S.; Chen M. W.; Hung A. W.; Keller T. H.; Luo D.; Kang C. Structural Dynamics of Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease Binding to Dipeptide Inhibitors. Structure 2017, 25 (8), 1242–1250. e3. 10.1016/j.str.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. A.; Ang M. J.; Joy J.; Poulsen A.; Wu W.; Ching S. C.; Hill J.; Chia C. S. Novel agmatine dipeptide inhibitors against the West Nile virus NS2B/NS3 protease: a P3 and N-cap optimization study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 62, 199–205. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell K. J.; Stoermer M. J.; Fairlie D. P.; Young P. R. Insights to substrate binding and processing by West Nile Virus NS3 protease through combined modeling, protease mutagenesis, and kinetic studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (50), 38448–58. 10.1074/jbc.M607641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.