Abstract

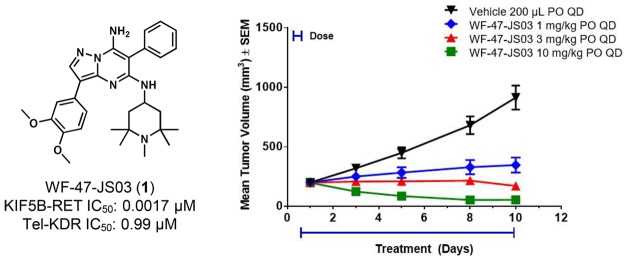

RET (REarranged during Transfection) kinase gain-of-function aberrancies have been identified as potential oncogenic drivers in lung adenocarcinoma, along with several other cancer types, prompting the discovery and assessment of selective inhibitors. Internal mining and analysis of relevant kinase data informed the decision to investigate a pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold, where subsequent optimization led to the identification of compound WF-47-JS03 (1), a potent RET kinase inhibitor with >500-fold selectivity against KDR (Kinase insert Domain Receptor) in cellular assays. In subsequent mouse in vivo studies, compound 1 demonstrated effective brain penetration and was found to induce strong regression of RET-driven tumor xenografts at a well-tolerated dose (10 mg/kg, po, qd). Higher doses of 1, however, were poorly tolerated in mice, similar to other pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine compounds at or near the efficacious dose, and indicative of the narrow therapeutic windows seen with this scaffold.

Keywords: RET, receptor tyrosine kinase, KIF5B, tolerability profile, KDR

The RET (REarranged during Transfection) proto-oncogene, first identified in 1985,1 is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that when activated by ligands of the glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family has constitutive effects on enteric nervous system formation and development.2,3 Somatic abnormalities associated with RET have been acknowledged as potential oncogenic drivers in several malignancies, including, but not limited to, thyroid cancer as well as a minor fraction of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases.4 Clinical cohorts positive for RET chromosomal rearrangement and subsequent gain-of-function kinase fusions, as are present in 1–2% of lung adenocarcinomas, may prove inherently susceptible to targeted treatment utilizing selective RET inhibitors.5,6 Therapeutically addressing the RET oncogene addiction paradigm in the context of NSCLC has drawn considerable attention in recent years7−10 as currently approved multikinase RET inhibitors have demonstrated clinical promise, albeit with reported instances of dose-limiting toxicity.11

Broad-spectrum kinase promiscuity is believed to be a principal liability for current therapeutics with significant anti-RET activity (e.g., cabozantinib12 and vandetanib13), with particular concern given to KDR (Kinase insert Domain Receptor) inhibition. Well-recognized detrimental downstream consequences of KDR inhibition, such as hypertension,14,15 can necessitate suboptimal dosing regimens of multikinase inhibitors and may limit the ability to fully engage RET-driven malignancies, thus increasing the probability of acquired drug resistance upon longer term exposure. Therefore, an increasingly potent and selective RET inhibitor may prove to more precisely engage RET in vivo, avoiding significant off-target toxicity, and further enabling the possibility of sought-after clinical outcomes in the aforementioned oncogenic cohorts. Ongoing clinical development work on RET-selective kinase inhibitors has resulted in a limited selection of preliminary results disclosed in the literature, most notably with regard to compounds LOXO-29216 and BLU-667.17 Herein, we describe our efforts toward selective and efficacious RET kinase inhibitors, resulting in the discovery of a series of pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-7-amines with strong in vitro anti-RET activity, wide degrees of attained selectivity against KDR, and robust in vivo murine efficacy. In addition, evidence of mouse brain penetration for pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine compound WF-47-JS03 (1) may portend the ability to subsequently treat RET-driven metastatic lesions in the brain with analogous compounds.

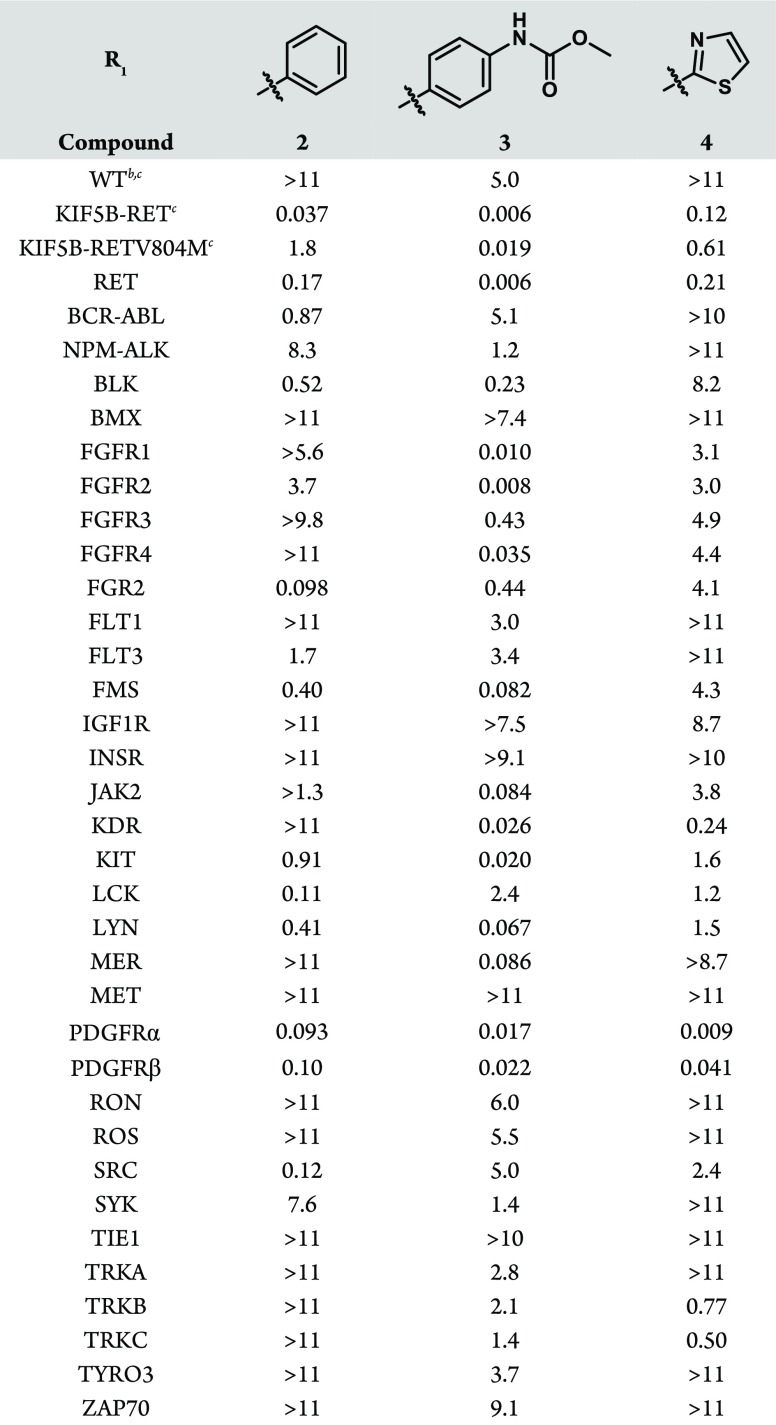

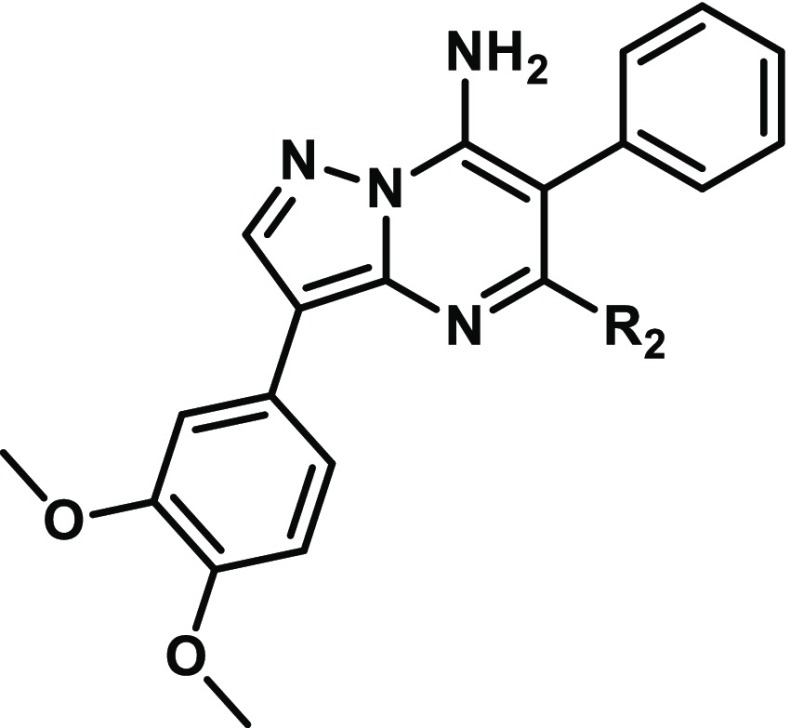

Our preliminary interest in a pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold came as a result of internal mining of historical Ba/F318 and enzymatic kinase data with subsequent selectivity rankings using Gini coefficient analysis.19 Resulting from this effort was hit compound 2, which was found to exhibit reasonable in vitro RET inhibitory activity in addition to sought-after selectivity against KDR. These factors, paired with its kinase selectivity across substantial regions of the kinome (Table 1), made the refinement of the compact pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine core an attractive starting point to initiate structure–activity relationship (SAR) investigation. RET activity was assayed in a cellular proliferation assay using the Ba/F3 cell line transfected with the oncogenic KIF5B-RET fusion gene, as well as related RET mutant strains. Selectivity against other RTKs was assayed with a panel of Ba/F3 lines transfected with various RTKs of interest.

Table 1. Cellular Activity and Kinase Selectivity of Hit Compound 2 and R1 Analoguesa.

Proliferation assays run in 1536-well format, employing Ba/F3 cells transfected with Tel fusions of the indicated kinase, and IC50 values reported in μM, unless otherwise noted.

Parental Ba/F3 cells utilized.

Assay run in 384-well format.

The SAR of the periphery was first examined at R1, where modification of the phenyl group was found to have significant effects on activity and selectivity profiles. These modifications, where diversity at R1 was generally introduced in the final step, were synthetically accessed through the condensation reaction of 4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine with diethyl malonate, with the subsequently constructed pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine core then readily converted to an appropriate bromide cross-coupling partner (Supporting Information). Of note is that the inclusion of a methyl carbamate group in the para position (3, Table 1) conferred enhanced potency against both the wild-type, KIF5B-RET fusion, and the relevant KIF5B-RETV804M gatekeeper mutant proteins, albeit with a significant erosion in the selectivity against KDR (Table 1). The inclusion of heterocycles at R1 was also feasible, as in the case of thiazole 4 (Table 1), giving rise to an altered activity/selectivity profile, but the SAR proved to be narrow. Due to the drawbacks associated with modifying R1, the phenyl group was accepted as the best option moving forward, and our attention turned to other locations where the kinase selectivity and physiochemical properties of the molecule could be optimized.

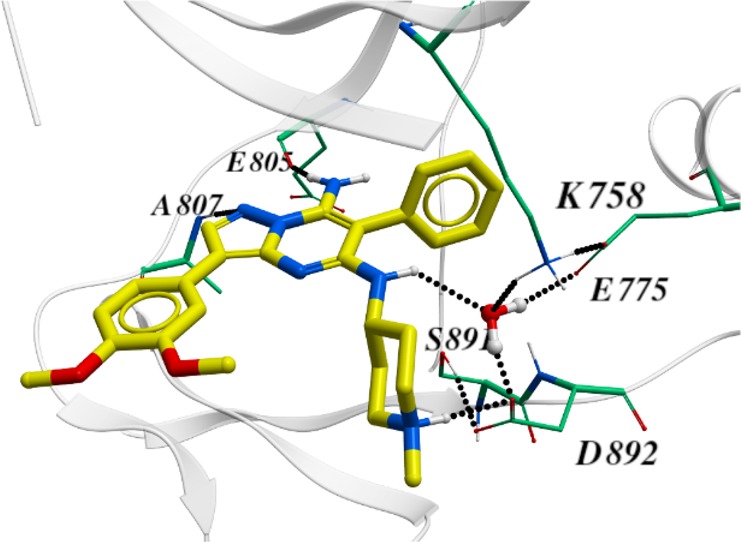

Through in silico analysis of docking models with RET constructs, it was hypothesized that the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine C5 position could yield improved selectivity against KDR through leveraging of regional binding pocket interactions with residues distinctive to RET. In particular, it was thought that the RET-specific residue S891 (C1045 in KDR), adjacent to the DFG motif, could be targeted20 by replacing the ether linkage of 2 with a nitrogen, as in 7. These 5-amino pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines yielded improved KDR selectivity when compared to ether-containing matched pairs in KIF5B-RET Ba/F3 experiments (Table 2). This difference is presumably due to improved, water-mediated interactions with residues E775 (αC-helix), K758 (β-3 strand), D892 (DFG motif), and S891 as evidenced by a cocrystal structure of RET with compound 7 (Figure 1).

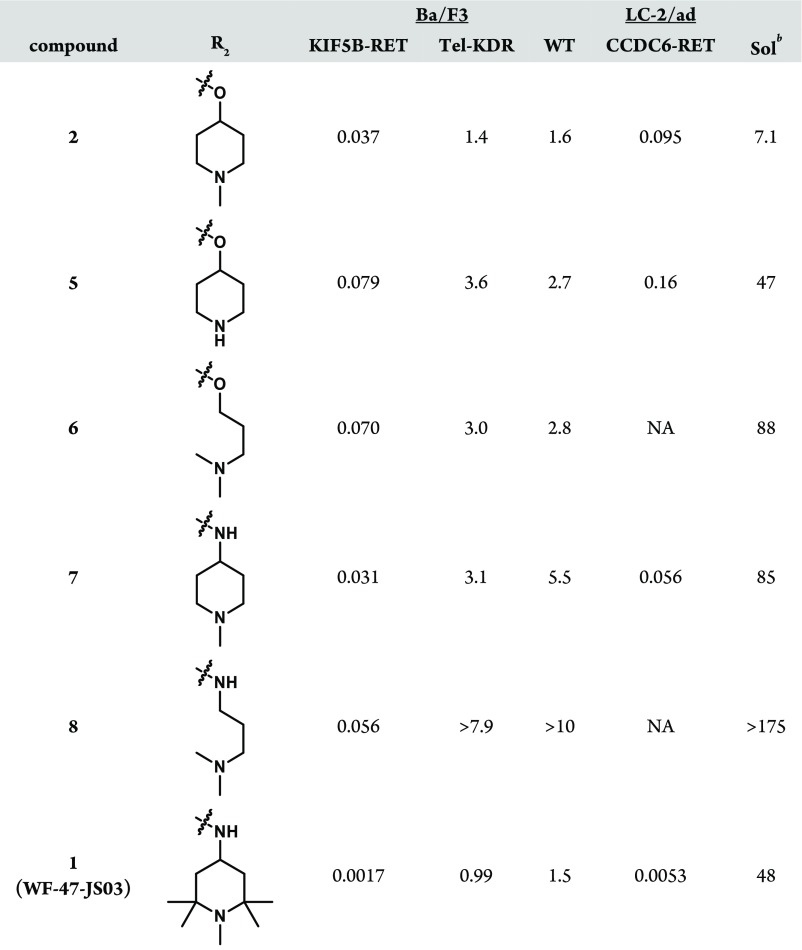

Table 2. Improved RET Potency, KDR Selectivity, and Solubility with R2 Modificationa.

Values reported as μM, and proliferation assays run in 384-well format to determine IC50.

Solubility assessed in pH 6.8 buffer.

Figure 1.

X-ray cocrystal structure of 7 and RET reveals significant water-mediated interactions of R2 substituent NH with key kinase residues E775, K758, D892, and S891.

Accessing these R2-substituted pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine compounds was accomplished by sequential condensation of 4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-5-amine with diethyl phenylmalonate, followed by chlorination, and reaction with ammonium hydroxide to give the intermediate 5-chloro-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-phenylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7-amine. From this intermediate, various N- and O-substituted analogues were then readily obtained via SNAr reaction (Supporting Information).

Aside from greatly improving the KDR selectivity to levels rarely achieved in vitro,21 changing the aforementioned substituent connectivity from oxygen to nitrogen resulted in much improved solubility for the scaffold (Table 2). Solubility was also improved either through reducing the lipophilicity of the piperidine ring or through increasing molecular flexibility. Both of these strategies, however, led to reduced potency against KIF5B-RET as exemplified by 5 and 6, respectively (Table 2). The breakthrough in this subseries came with the discovery of compound 1, where the additional hydrophobicity of the 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidin-4-amine group served to improve both the KIF5B-RET potency and KDR selectivity index by greater than 10-fold while also improving the solubility >6-fold relative to subseries parent compound 2 (Table 2). Compound 1 also shows noteworthy activity against a patient-derived, LC-2/ad lung cancer cell line bearing the CCDC6-RET fusion gene (Table 2). Although 1 still has significant off-target kinase activities (see the Supporting Information), its superior selectivity for RET versus KDR and Ba/F3 wild-type cell lines gave us a tool to explore how uncoupling the RET and KDR activities affects efficacy and toxicity.

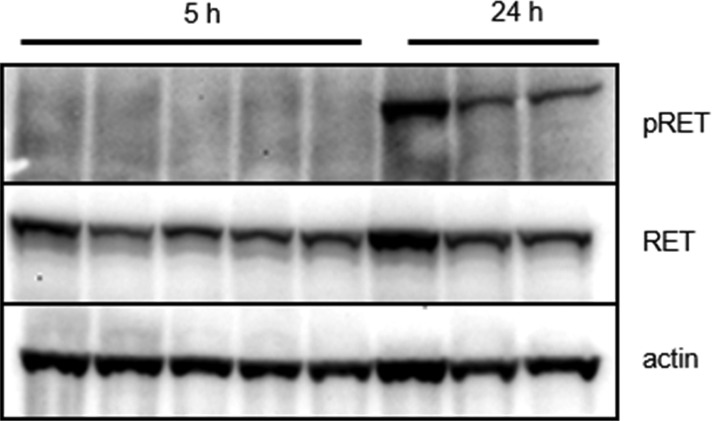

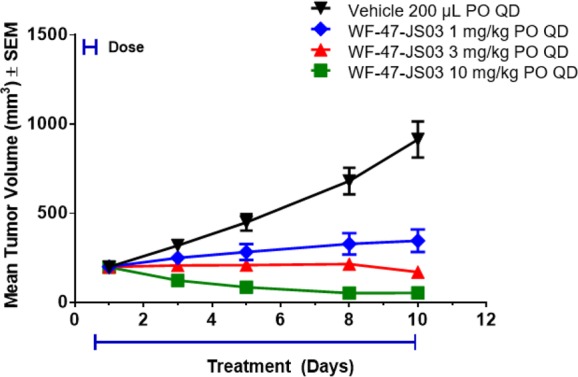

The pharmacokinetic profile of compound 1 in mice demonstrated good oral plasma exposure, half-life, and bioavailability as well as significant brain penetration (Table 3); and it supported subsequent in vivo efficacy studies for the compound. In a relevant clonal RIE KIF5B-RET subcutaneous xenograft tumor model, where mice were dosed orally with 1 at 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg once daily for 14 days, tumors regressed rapidly and outwardly demonstrated a loss of visible vasculature at all doses. However, after several days of compound administration, significant weight loss was observed among multiple mice in the 60 and 30 mg/kg arms of the study, where subsequent necropsy in these animals revealed substantial lung toxicity (red and mottled appearance/lung collapse/signs of hemorrhaging). Conversely, in the 10 mg/kg cohort, dosing with 1 seemed well-tolerated and led to significant tumor regression (Supporting Information). In a follow-on 10 day study aimed at evaluating the efficacy and pharmacodynamics of lower doses of 1, doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg were all well-tolerated and found to induce tumor inhibition, stasis, and regression, respectively, consistent with observed dose-proportional plasma exposures (Figure 2, Supporting Information). The substantial efficacy demonstrated in vivo for 1 in the 10 mg/kg group precluded the analysis of vestigial tumors, but both the 1 and 3 mg/kg groups demonstrated significant intratumoral RET phosphorylation inhibition via Western Blot at 5 h post-dose time points, although abated considerably by 24 h (Figure 3, Supporting Information).

Table 3. PK Parameters and Brain Tissue Exposurea.

| brain/plasma ratio |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | route | dose | CL (mL/min/kg) | VSS (L/kg) | t1/2 (h) | AUC (h·μM) | Cmax (μM) | F (%) | AUC | Cmax |

| 1 (WF-47-JS03) | iv | 5 | 51 | 13 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 1.1 | |||

| pob | 20 | 11 | 12 | 0.73 | 94 | 0.94 | 0.81 | |||

| 9 (YA-14-WJ39) | iv | 5 | 54 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 1.6 | |||

| po | 20 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 0.88 | 64 | 0.15 | 0.13 | |||

| 10 (SC-89-VU43) | iv | 2 | 19 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 0.94 | |||

| po | 10 | 3.7 | 8.7 | 0.82 | 62 | NA | NA | |||

| 11 | iv | 2 | 110 | 11 | 1.6 | 0.49 | 0.45 | |||

| po | 10 | 2.2 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 14 | NA | NA | |||

PK studies run in Balb/c mice.

HCl salt used for dosing.

Figure 2.

RET inhibitor compound 1 (WF-47-JS03) significantly inhibits tumor growth in RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft mice and is well tolerated at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg in the 10 day study.

Figure 3.

Western Blot confirmation of intratumoral RET target engagement in RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft mice at tumor stasis dose (3 mg/kg, po, MC/Tween80, suspension) at the 5 h time point after 10 days of compound 1 administration.

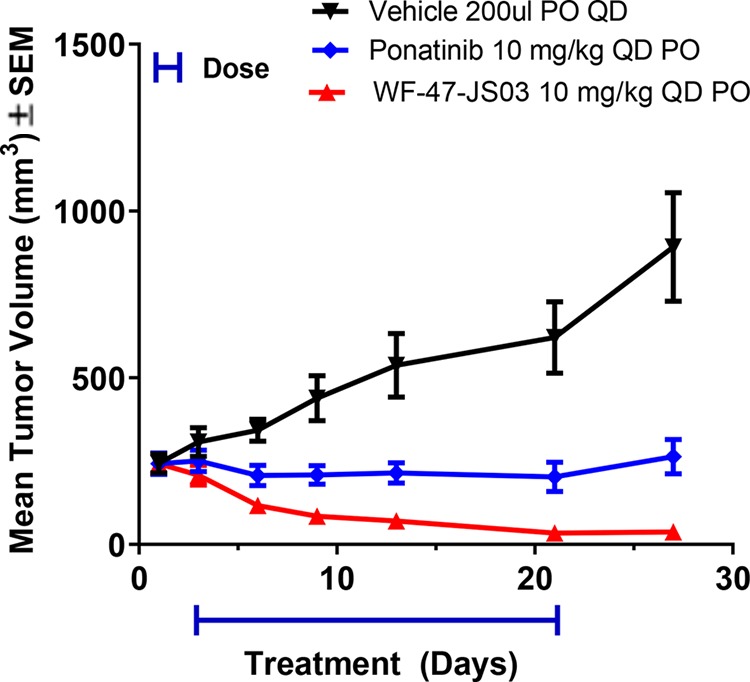

Upon establishment of a highly efficacious and tolerated dose level in the aforementioned RIE KIF5B-RET clonal model, we then sought assessment of this 10 mg/kg dose of 1 in the context of a disease-relevant LC-2 tumor tissue model utilizing the pan-RTK/RET inhibitor ponatinib22,23 as a positive control. This study, designed with daily oral dosing for 21 days followed by post-study monitoring, demonstrated exceptional efficacy along with sustained tumor abatement following cessation of treatment (Figure 4). Administration of the compound was largely tolerated; however, following the termination of dosing, one mouse was euthanized on day 24 due to rapid weight loss, where subsequent necropsy revealed kidney effects.

Figure 4.

Treatment of LC-2/ad tumor-bearing mice with 1 (WF-47-JS03) for 21 days is well-tolerated and leads to significant regression at 10 mg/kg.

The toxicity profile of 1 was further studied in a 4 week mouse study with a specific emphasis on detecting any significant neuronal changes due to the high brain penetration previously observed for the compound (Table 3). At 10 mg/kg qd for 1, histopathological analysis revealed no effect on neurons in the brain or gastrointestinal system, and there were no noticeable changes in the lung; however, mild to moderate findings in the pancreas (10/10 animals, vacuolation), lymph nodes (2/10, germinal center decreased cellularity), and spleen (7/10, marginal zone depletion) were observed. The lack of effects on brain or GI neurons suggests that treatment of RET-driven metastatic lesions in the brain could be possible without significant on-target RET-driven neuronal effects. Current options for these types of brain-metastasized cancers are limited, and these include coadministration of vandetanib and everolimus (the latter being an mTOR inhibitor employed to increase brain exposures24), alectinib at elevated doses,25 and potentially LOXO-29216 and BLU-66726 where partial responses in the brain have been disclosed.

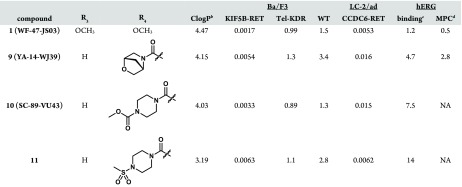

Based upon learnings from the efficacy studies of compound 1 conveyed above, we sought to screen additional pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines for efficacy in relevant murine models in the hope of achieving an improved therapeutic index and/or a more manageable toxicity profile while, in addition, attempting to mitigate potential human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) and predicted phospholipidosis risks.27 Initial efforts toward reduction of the strong hERG inhibition of 1 (Table 4) involved removal or replacement of the 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidin-4-amine group basic nitrogen. These attempts, however, resulted in a substantial loss of potency, presumably due to a strong binding interaction of the basic amine with RET residue D892 (DFG motif), as was exhibited by 7 (Figure 1). Therefore, we concentrated our efforts on installation of polarity at R4 to reduce overall lipophilicity. Specifically, when the 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl group is replaced by a variety of R4 amides, the additional hydrophilicity results in a reduction in hERG binding of up to 12-fold without a substantial loss of potency in both KIF5B-RET transfected Ba/F3 cells and the LC-2/ad cell line (Table 4). Disappointingly, the most promising compound of the subseries, compound 11, which demonstrated substantially reduced hERG binding, exhibited poor oral exposure and bioavailability, precluding advancement to in vivo efficacy studies (Table 3). In contrast, compounds YA-14-WJ39 (9) and SC-89-VU43 (10) demonstrated relatively balanced in vitro and in vivo properties, making the compounds promising candidates for further in vivo studies.

Table 4. Increased Polarity at R4 Reduces hERG Liabilitya.

IC50 values reported as μM.

StarDrop calculation.

Assessed with 3H-dofetilide.

Manual patch clamp.

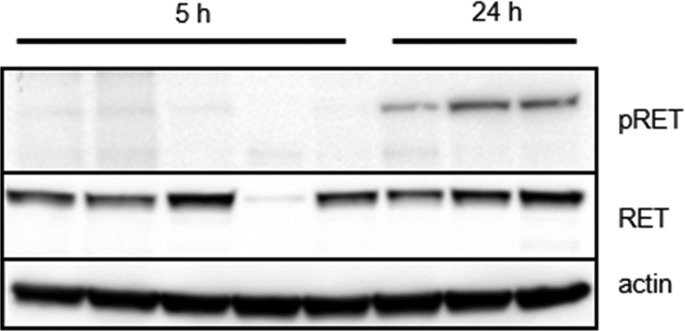

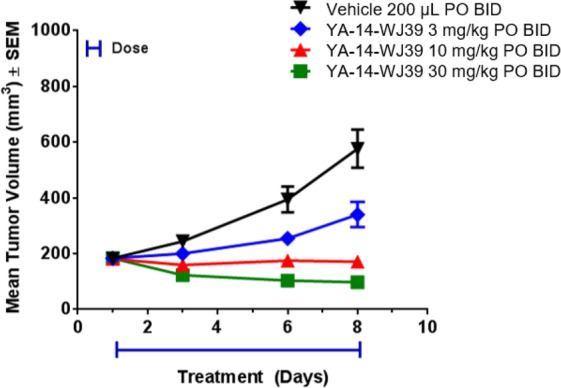

Subsequently, twice daily dosing was selected to evaluate the efficacy of 9 in an abbreviated version of the RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft model, with doses of 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg for a period of 8 days (Figure 5). Compound 9 was well tolerated, with no adverse events observed in any of the treatment arms. Administration of 9 at 30 mg/kg demonstrated moderate tumor regression, while stasis and inhibition were observed for the 10 and 3 mg/kg cohorts, respectively. Plasma exposures from the study were found to be dose proportional (Supporting Information) as well as consistent with single dose pharmacokinetics (PK) data (Table 3). Also, tumor concentrations were found to be high with respect to plasma, suggesting good tumor penetration potential (Supporting Information). Tumor analysis from the study revealed strong inhibition of pRET at 5 h post-BID dosing at 30 mg/kg, but inhibition was not sustained at later time points similar to that seen with compound 1 (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Treatment with RET inhibitor compound 9 (YA-14-WJ39) demonstrates moderate tumor regression in RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft mice and is well tolerated at 30 mg/kg in the 8 day study.

Figure 6.

Significant intratumoral RET target engagement is demonstrated in RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft mice at the tumor regression dose (30 mg/kg, po, MC/Tween80, suspension) at the 5 h time point after 8 days of compound 9 administration. Tumor volume was extremely small in one mouse from the 5 h cohort, leading to likely profiling of stroma tissue.

However, in contrast to 9, administration of compound 10 was poorly tolerated in the mouse RIE KIF5B-RET xenograft efficacy model, where twice daily administration of 3, 10, 30, and 60 mg/kg for a period of 8 days resulted in the manifestation of severe lung hemorrhaging and hypothermia in mice at all doses except 3 mg/kg (Supporting Information). The hemorrhagic phenotype observed in this case was similar to that described above with 1 (vide supra) and was also found in subsequent studies with dosing of compounds 2 and 4, suggesting that the toxicity observed is scaffold- and/or target-based due to the significant structural variability of substituents, as well as differences in kinase off-target profiles of the tested compounds. Ultimately, poor therapeutic windows and precipitous onset of severe lung hemorrhagic events occurring in murine models led us to discontinue work on the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold and turn our attention to the study of an alternative core scaffold.

In summary, we have discovered a series of potent pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine RET inhibitors with high selectivity over KDR and moderate overall kinase selectivity. Compound 1 was found to be highly efficacious in RET-driven mouse xenograft studies and was well-tolerated at the efficacious 10 mg/kg qd dose over 28 days of dosing. Importantly, no effects were observed in GI or brain neurons, evidence that tumor inhibition is achievable with no overt on-target neuronal effects. However, at higher doses of 1, and with a series of follow-up compounds at or near the efficacious dose, severe hemorrhagic lung effects were observed. This ultimately led us to discontinue efforts on the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold and pursue work on other scaffolds. We anticipate disclosing a summary of this work at a future date.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Hollenbeck for LCMS-ES data and David Jones for NMR data. We would also like to thank the staff at BL5.0.3 Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA), a DOE Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, supported in part by the ALS-ENABLE program funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant P30 GM124169-01.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- RET

rearranged during transfection

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- GDNF

glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor

- NSCLC

nonsmall-cell lung cancer

- KDR

kinase insert domain receptor

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- RIE

rat intestinal epithelial

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00015.

Experimental procedures, characterization, and 1H NMR spectra of all compounds; in vitro assay descriptions; cellular kinase panel activity for compounds 1 and 6–11; PK data for compounds 1 and 9–11; in vivo efficacy/tolerability study design and results for compounds 1, 9, and 10; 4 week mouse toxicity study design and results for compound 1 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

PDB accession code is 6VHG and designated for immediate release upon publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- Takahashi M.; Ritz J.; Cooper G. M. Activation of a novel human transforming gene, ret, by DNA rearrangement. Cell 1985, 42, 581–588. 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delalande J.-M.; Barlow A. J.; Thomas A. J.; Wallace A. S.; Thapar N.; Erickson C. A.; Burns A. J. The receptor tyrosine kinase RET regulates hindgut colonization by sacral neural crest cells. Dev. Biol. 2008, 313, 279–292. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan L. M. GDNF and the RET receptor in cancer: new insights and therapeutic potential. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1873. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A. T.; Hsu P. P.; Awad M. M.; Engelman J. A. Tyrosine kinase gene rearrangements in epithelial malignancies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 772–787. 10.1038/nrc3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falchook G. S.; Ordóñez N. G.; Bastida C. C.; Stephens P. J.; Miller V. A.; Gaido L.; Jackson T.; Karp D. D. Effect of the RET inhibitor vandetanib in a patient with RET fusion-positive metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, e141–e144. 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.5016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte G.; Ulivi P.; Verlicchi A.; Cravero P.; Delmonte A.; Crinò L. Targeting RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: future prospects. Lung Cancer: Targets Ther. 2019, 10, 27–36. 10.2147/LCTT.S192830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mologni L.; Gambacorti-Passerini C.; Goekjian P.; Scapozza L. RET kinase inhibitors: a review of recent patents (2012–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 91–99. 10.1080/13543776.2017.1238073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R. Jr.; Sadeghi-Nejad A. Role of RET protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment RET-driven thyroid and lung cancers. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 128, 1–17. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary C.; Xu W.; Pavlakis N.; Richard D.; O’Byrne K. Rearranged during transfection fusions in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 620–625. 10.3390/cancers11050620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. Y.; McCusker M. G.; Russo A.; Scilla K. A.; Gittens A.; Arensmeyer K.; Mehra R.; Adamo V.; Rolfo C. RET fusions in solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 81, 101911–101925. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. Progress in discovery of KIF5B-RET kinase inhibitors for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3672–3681. 10.1021/jm501464c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart C. D.; De Boer R. H. Profile of cabozantinib and its potential in the treatment of advanced medullary thyroid cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2013, 6, 1–7. 10.2147/OTT.S27671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Lee J. K.; Ahn M. J.; Kim D. W.; Sun J. M.; Keam B.; Kim T. M.; Heo D. S.; Ahn J. S.; Choi Y. L.; Min H. S.; Jeon Y. K.; Park K. Vandetanib in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer-harboring RET rearrangement: a phase II clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28 (2), 292–297. 10.1093/annonc/mdw559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dy G. K.; Adjei A. A. Understanding, recognizing, and managing toxicities of targeted anticancer therapies. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 249–279. 10.3322/caac.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D. R.; Shah R. R.; Morganroth J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: their on-target toxicities as potential indicators of efficacy. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 413–426. 10.1007/s40264-013-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcheti V.; Bauer T.; Subbiah V.; Cabanillas M.; Lakhani N.; Wirth L.; Oxnard G.; Shah M.; Sherman E.; Smith S.; Eary T.; Cruickshank S.; Tuch B.; Ebata K.; Nguyen M.; Corsi-Travali S.; Rothenberg S.; Drilon A. LOXO-292, a potent, highly selective RET inhibitor, MKI-resistant RET fusion-positive lung cancer patients with and without brain metastases. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, S1778. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.09.399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah V.; Gainor J. F.; Rahal R.; Brubaker J. D.; Kim J. L.; Maynard M.; Hu W.; Cao Q.; Sheets M. P.; Wilson D.; Wilson K. J.; DiPietro L.; Fleming P.; Palmer M.; Hu M. I.; Wirth L.; Brose M. S.; Ou S.-H. I.; Taylor M.; Garralda E.; Miller S.; Wolf B.; Lengauer C.; Guzi T.; Evans E. K. Precision targeted therapy with BLU-667 for RET-driven cancers. Cancer Discovery 2018, 8, 836–849. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmuth M.; Kim S.; Gu X.; Xia G.; Adrian F. Ba/F3 cells and their use in kinase drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2007, 19, 55–60. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328011a25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graczyk P. P. Gini coefficient: a new way to express selectivity of kinase inhibitors against a family of kinases. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 5773–5779. 10.1021/jm070562u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R.; Bowler K. A.; Burns E. M.; Chapman P. J.; Fairweather E. E.; Fritzl S. J. R.; Goldberg K. M.; Hamilton N. M.; Holt S. V.; Hopkins G. V.; Jones S. D.; Jordan A. M.; Lyons A. J.; March H. N.; McDonald N. Q.; Maguire L. A.; Mould D. P.; Purkiss A. G.; Small H. F.; Stowell A. I. J.; Thomson G. J.; Waddell I. D.; Waszkowycz B.; Watson A. J.; Ogilvie D. J. The discovery of 2-substituted phenol quinazolines as potent RET kinase inhibitors with improved KDR selectivity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 112, 20–32. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck Eidam H.; Russell J.; Raha K.; DeMartino M.; Qin D.; Guan H. A.; Zhang Z.; Zhen G.; Yu H.; Wu C.; Pan Y.; Joberty G.; Zinn N.; Laquerre S.; Robinson S.; White A.; Giddings A.; Mohammadi E.; Greenwood-Van Meerveld B.; Oliff A.; Kumar S.; Cheung M. Discovery of a first-in-class gut-restricted RET kinase inhibitor as a clinical candidate for the treatment of IBS. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 623–628. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco V.; Buonocore P.; Muthu M.; Torregrossa L.; Basolo F.; Billaud M.; Gozgit J. M.; Carlomagno F.; Santoro M. Ponatinib (AP24534) is a novel potent inhibitor of oncogenic RET mutants associated with thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E811–E819. 10.1210/jc.2012-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F. H.; Putoczki T. L.; Stylli S. S.; Luwor R. B. Ponatinib: a novel multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor against human malignancies. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 635–645. 10.2147/OTT.S189391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah V.; Berry J.; Roxas M.; Guha-Thakurta N.; Subbiah I. M.; Ali S. M.; McMahon C.; Miller V.; Cascone T.; Pai S.; Tang Z.; Heymach J. V. Systemic and CNS activity of the RET inhibitor vandetanib combined with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in KIF5B-RET re-arranged non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases. Lung Cancer 2015, 89, 76–79. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. J.; Kennedy E.; Sequist L. V.; Brastianos P. K.; Goodwin K. E.; Stevens S.; Wanat A. C.; Stober L. L.; Digumarthy S. R.; Engelman J. A.; Shaw A. T.; Gainor J. F. Clinical activity of alectinib in advanced RET-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 2027–2032. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainor J. F.; Lee D. H.; Curigliano G.; Doebele R. C.; Kim D.-W.; Baik C. S.; Tan D. S.-W.; Lopes G.; Gadgeel S. M.; Cassier P. A.; Taylor M. H.; Liu S. V.; Besse B.; Thomas M.; Zhu V. W.; Zhang H.; Clifford C.; Palmer M.; Turner C. D.; Subbiah V. Clinical activity and tolerability of BLU-667, a highly potent and selective RET inhibitor, in patients (pts) with advanced RET-fusion+ non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 9008. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier D. J.; Gehlhaar D.; Tilloy-Ellul A.; Johnson T. O.; Greene N. Evaluation of a published in silico model and construction of a novel Bayesian model for predicting phospholipidosis inducing potential. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 1196–1205. 10.1021/ci6004542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.