Abstract

Alkaloids are a large cluster of molecules found in Mother Nature all over the world. They are all secondary compounds and collection of miscellaneous elements and biomolecules, derived from amino acids or from transamination. This diverse chemical group is categorized, based on the amino acids that deliver their nitrogen atom and part of their skeleton. Alkaloids from a similar origin or having the same basic nucleus may have dissimilar biosynthetic pathways and different biological activity. They are derived from l-phenylalanine, l-tyrosine, anthranilic acid or acetate, l-histidine, l-ornithine, nicotinic acid, and l-lysine. Apart from other types of alkaloids, indole, tropane, and isoquinoline alkaloids are very important. People from all over the world are using them in their everyday life. Alkaloids can also have an animal origin, which may be endogenous or exogenous. This chapter highlights the phytochemistry of the main representatives among the diverse group of alkaloids. This chapter also focuses on their extraction, purification, fractionation, identification, and quantification procedures. A fundamental understanding of the biological activity of important alkaloids is also highlighted in this chapter. With the potential of revealing new compounds and diverse pharmacological properties, alkaloids still embrace a great potential for the future of drug discovery.

Keywords: Indole alkaloid, Tropane alkaloid, Isoquinoline alkaloid, Phytochemistry, Biological activity

15.1. Introduction

Plants are the renowned cradle of traditional medicine system that assuages human diseases and promotes health for thousands of years (Rupani and Chavez, 2018; Sadia et al., 2018). Plants are a rich reservoir of a vast array of active constituents that have significant therapeutic applications like antiviral, anticancer, analgesic, antitubercular (Ishtiyak and Hussain, 2017; Uniyal et al., 2006). Among them, alkaloids are the important secondary metabolites that were initially discovered and used as early as 4000 years ago and are well recognized for their rich therapeutic potential (Amirkia and Heinrich, 2014). Based on their heterocyclic ring system and biosynthetic precursor, alkaloids are classified into diverse categories, viz. indole, purine, quinoline, isoquinoline, tropane, imidazole, among others (Kaur and Arora, 2015; Roy, 2017). Alkaloids have antiproliferative, antibacterial, antioxidant potential, which can be used for the development of drugs (Qiu et al., 2014). This therapeutic potential of alkaloids grows up their industrial application. Numerous research have been carried out in pharmaceutical properties of different alkaloids extracted from plants. In this chapter, we will systematically summarize the chemistry, isolation and identification techniques, biological activities along with potential applications in a single platform.

Alkaloids are an assembly of naturally occurring chemical composites, which typically comprise basic nitrogen atoms. They may also contain some neutral or weakly acidic compounds (Manske and Holmes, 2014; McNaught and McNaught, 1997). Few synthetic compounds are also considered as alkaloids too (Lewis, 1998). Apart from carbon, nitrogen, or hydrogen, alkaloids may comprise sulfur and rarely bromine, phosphorus, or chlorine (Knunyants and Zefirov, 1988).

These secondary metabolites are formed by a large variety of entities, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. Because of their vast array of pharmacological actions (anticancer, antimalarial, anesthetic, stimulant), they are purified from the crude extract by acid-base extraction (Ziegler and Facchini, 2008).

The word “alkaloid” was first coined by the German chemist Carl F. W. Meissner in 1819, derived from the Arabic name al-qali, which is associated to the plant from which soda was first sequestered (Croteau et al., 2000). Alkaloids are low-molecular-weight structures and form approximately 20% of plant-based secondary metabolites (Kaur and Arora, 2015). So far, approximately 12,000 alkaloids are isolated from various genera of the plant kingdom (Kaur and Arora, 2015).

Alkaloids are mostly solids and are known to occur in higher plants. They are prevalent in the plants belonging to the following botanical families: Apocynaceae, Annonaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Berberidaceae, Boraginaceae, Gnetaceae, Liliaceae, Leguminoceae, Lauraceae, Loganiaceae, Magnoliaceae, Menispermaceae, Papaveraceae, Piperaceae, Rutaceae, Rubiaceae, Ranunculaceae, Solanaceae, etc. (Boit, 1961).

15.2. Phytochemistry and classification of alkaloids

15.2.1. Classification established upon the biogenesis

Alkaloids illustrate large diversity not only in their botanical and biochemical origin but also in structure and pharmacological action. In this connection, various systems of classification are possible. From a structural perception, alkaloids can be classified, based on their molecular precursor, structures, and origins or on the biological pathways used to obtain the molecule.

There are three central types of alkaloids: (1) true alkaloids, (2) protoalkaloids, and (3) pseudoalkaloids. True alkaloids and protoalkaloids are produced from amino acids, whereas pseudoalkaloids are not derived from these compounds.

15.2.1.1. True alkaloids

This type of alkaloids are obtained from amino acids and they share a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic ring. They are highly reactive in nature and have potent biological activity. They form water-soluble salts, and many of them are crystalline in nature, which conjugates with acid and forms a salt. Almost all true alkaloids are bitter in taste and solid, except nicotine, which is a brown liquid (Aniszewski, 2007).

Their occurrence in plants occurs in three forms: (a) in Free-state, (b) as N-oxide, or (c) as salts. Various amino acids like l-phenylalanine/l-tyrosine, l-ornithine, l-histidine, l-lysine are the main sources of true alkaloids (Table 15.1 ) (Dewick, 2002; Pelletier, 1999). Cocaine, morphine, quinine are the common true alkaloids found in nature.

Table 15.1.

Amino acid and their involvement in alkaloid synthesis (Aniszewski, 1994, Aniszewski, 2007; Bentley, 2006; Chini et al., 1992; Fusco and Giacovazzo, 1997; Hartmann, 1999; Ihara and Fukumoto, 1996; Leonard, 1999).

| Alkaloid type | Major group of alkaloid | Chemical group of alkaloid | Amino acid precursor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Ergot alkaloids Pyrroloindole alkaloids Indole alkaloids Aspidosperma alkaloids Quinoline alkaloids |

l-Threonine l-Proline l-Tryptophan l-Serine |

| Protoalkaloids | Terpenoid indole alkaloids | ||

| Arginine-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Marine alkaloids |

l-Asparagine l-Alanine l-Aspartic acid l-arginine |

| Ornithine-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Pyrrolizidine alkaloids Tropane alkaloids Pyrrolidine alkaloids |

l-Ornithine |

| Histidine-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Manzamine alkaloids Imidazole alkaloids |

l-Histidine |

| Nicotinic acid-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Sesquiterpene pyridine alkaloids Pyridine alkaloids |

Nicotinic acid |

| Lysine-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Indolizidine alkaloids Quinolizidine alkaloids Piperidine alkaloids |

l-Lysine l-Leucine l-Isoleucine |

| Anthranilic acid-derived alkaloids | True alkaloid | Acridine alkaloids Quinoline alkaloids Quinazoline alkaloids |

Anthranilic acid |

| Tryptophan-derived alkaloids | Protoalkaloids | Terpenoid indole alkaloids |

l-Threonine l-Proline l-Tryptophan l-Serine |

| Tyrosine-derived alkaloids | Protoalkaloids | Phenylethylamine alkaloids | l-Tyrosine |

15.2.1.2. Protoalkaloids

This type of alkaloids contains a nitrogen atom, which is derived from an amino acid but is not part of the heterocyclic ring system. l-Tryptophan and l-tyrosine are the main precursors of this type of alkaloids. This minor group is structurally composed of simple alkaloids. Yohimbine, mescaline, and hordenine are the main alkaloids of this type. They are used in various health disorders, including mental illness, pain, and neuralgia (Chini et al., 1992).

15.2.1.3. Pseudoalkaloids

The basic carbon skeleton of pseudoalkaloids is not directly derived from amino acids; instead, they are connected with amino acid pathways where they are derived from by amination or transamination reaction from forerunners or postcursors of amino acid (Dewick, 2002; Jakubke and Jeschkeit, 1994). Nonamino-acid precursors can also produce pseudoalkaloids. They can be phenylalanine or acetate derived. Capsaicin, caffeine, ephedrine are very common examples of pseudoalkaloids (Table 15.2 ).

Table 15.2.

Involvement of parent compound in pseudoalkaloids synthesis (Aniszewski, 2007).

| Parent compounds | Precursor compound | Chemical group of alkaloids | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoid | Geraniol | Terpenoid Alkaloids |

Gentianine Aconitine β-Skytanthine Actinidine |

| Sesquiterpene | Acetate | Sesquiterpene Alkaloids |

Evonoline Cassinine Evorine Celapanin |

| Phenyl | Ferulic acid | Aromatic Alkaloids |

Capsaicin |

| Piperidine | Acetate | Piperidine Alkaloids |

Pinidine Coniceine Coniine |

| Purine | Adenine/Guanine | Purine alkaloids | Theophylline Theobromine Caffeine |

15.2.2. Classification established upon the ring structure

This is the most comprehensively established classification, based on the presence of a basic heterocyclic nucleus in their structure.

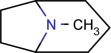

15.2.2.1. Tropane alkaloid (Biastoff and Dräger, 2007; Gossauer, 2003; Hemscheidt, 2000)

This category of alkaloids has tropane (C4N skeleton) nucleus. They are abundantly found in the Solanaceae family. They are derived from ornithine and acetoacetate. Structurally, pyrrolines are the precursor of these type of alkaloids. Maximum of them are esters of mono, di, trihydroxytropane, having a wide range of hydroxylation arrangements. Cocaine, atropine, scopolamine, and their derivatives are widely studied since the 19th century because of their enormous pharmacological actions (Fig. 15.1 ).

Fig. 15.1.

Basic structure of the tropane nucleus.

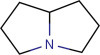

15.2.2.2. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (Hartmann and Ober, 2000; Liddell, 2002; Rizk, 1990; Robins, 1982; Schardl et al., 2007; Wrobel, 1985)

The pyrrolizidine nucleus is distinctive of this group of alkaloids. They occur in the plants from Asteraceae and Fabaceae family. Majority of pyrrolizidine alkaloids occur in the plants as N-oxides, whose role being lost during the isolation process. They have extensively reviewed alkaloids because of their toxic effects, especially liver damage. These alkaloids enter into the food chain and become antifeedants for the animals who eat them. Senecionine is the popular alkaloid of this type (Fig. 15.2 ).

Fig. 15.2.

Basic structure of the Pyrrolizidine nucleus.

15.2.2.3. Piperidine alkaloids (Strunz and Findlay, 1985)

Piperidine nucleus is the basic ring system of this group of alkaloids. Monocycle compounds with the C5N nucleus is the important feature of true piperidine alkaloids. Presence of odor is the common feature of piperidine alkaloids. They exert chronic neurotoxicity. Many of them are originated from plants. Although piperidine itself is a lysine-derived alkaloid, some of the piperidine alkaloids also derived from acetate, acetoacetate, in an analogous fashion to the simple pyrrolidine alkaloids. Lobeline is one of the important alkaloids in this group (Fig. 15.3 ).

Fig. 15.3.

Basic structure of the piperidine nucleus.

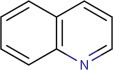

15.2.2.4. Quinolines alkaloid (Michael, 2008; Soares et al., 2007)

This type of quinolone-nucleus-containing alkaloid is achieved exclusively from the bark of the Cinchona plant. But a variety of simple heteroaromatic quinolines are also isolated from various marine sources (4,8-quinolinediol from cephalopod ink and 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline from a marine pseudomonad). The major alkaloid of this specific group is cinchonine, cinchonidine, quinine, and quinidine (Fig. 15.4 ).

Fig. 15.4.

Basic structure of the Quinoline nucleus.

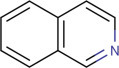

15.2.2.5. Isoquinoline alkaloids (Baker, 1996; Bentley, 2006; Hu et al., 2003a; Schiff Jr, 1987; Thomas, 2004)

Isoquinoline alkaloids are an extremely large group of alkaloids mostly occurring in higher plants, but few groups are also isoquinolinoid marine alkaloids. Isoquinoline nucleus is the basic structural feature. These groups of alkaloids have huge types of medicinal properties like antiviral, antifungal, anticancer, antioxidant, antispasmodic, and an enzyme inhibitor. Morphine and codeine are the major and widely studied isoquinoline alkaloids. They are derived from tyrosine or phenylalanine. They are made from a predecessor of dopamine (3,4-dihydroxytryptamine) associated with a ketone or aldehyde. This group of alkaloids is further classified as follows: Simple isoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., salsoline, mimosamycin), benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., reticuline, imbricatine), bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., fumaricine), manzamine alkaloids (e.g., manzamine a), pseudobenzylisoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., polycarpine, ledecorine), secobisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., baluchistanamine), bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids containing one ether link (e.g., dauricine), bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids containing two ether links (e.g., berbamine), bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids containing aryl links only (e.g., pisopowetine), bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids containing one aromatic link and one or two ether links (e.g., rodiasine) (Fig. 15.5 ).

Fig. 15.5.

Basic structure of the isoquinoline nucleus.

15.2.2.6. Indole alkaloids (Fresneda and Molina, 2004; Kam and Choo, 2006; Kawasaki and Higuchi, 2005; Knölker, 2008; Mukherjee and Menge, 2000; Schardl et al., 2006; Somei and Yamada, 2004; Somei et al., 2000)

This is the largest and most interesting alkaloid group derived from tryptophan. The important alkaloids from this group include simple tryptamine derivatives, carbazoles (where the ethanamine chain has been lost), a diversity of alkaloids where one or more prenyl residues are combined with tryptamine, and others where integration of regular monoterpenoid or diterpenoid units occurred. Although structural diversity varies according to the terrestrial and marine source, classical research studies have been carried out on alkaloids from both origins and the fungal source. Polyhalogenation is a common feature of these alkaloids. They are further classified as follows: simple indole alkaloids (e.g., Aplysinopsin, Gramine), bisindoles (e.g., Indirubin, 6,6′-Dibromoindigotin), simple tryptamine alkaloids (e.g., Tryptamine), cyclotryptamine alkaloids (e.g., Physostigmine), quinazolinocarbazole alkaloids (e.g., Rutaecarpine), β-carboline alkaloids (e.g., Harman), carbazole alkaloids (e.g., Ekeberginine), indolonaphthyridine alkaloids (e.g., Canthin-6-one), ergot alkaloids (e.g., ergotamine) (Fig. 15.6 ).

Fig. 15.6.

Basic structure of the indole nucleus.

15.2.2.7. Steroidal alkaloids (Ata and Andersh, 2008; Dey et al., 2018; Habermehl, 1967; Keeler, 1986; Ripperger, 1998; Tomko and Votický, 1973; Zhao et al., 2015)

1,2-Cyclopentane phenanthrene ring system is the characteristic of this type of alkaloids. They are typically originated from higher plants, which belong to Liliaceae, Solanaceae, Apocynaceae, Buxaceae families, but some are also isolated from amphibians too. These alkaloids are divided into various other subtypes, among them various types of aminopregnanes are the simplest type. The others types of steroidal alkaloids are Salamandra type (e.g., cycloneosamandione), jerveratrum type (e.g., jervine), spirosolane type (e.g., soladulcidine), solanidine type (e.g., rubijervine), cerveratrum type (e.g., 3,6-cevanediol), conanine type (e.g., didymeline), Buxus type (e.g., cyclobuxine), pregnane type (e.g., 20α-dimethylamino-3β-senecioylamino-16β-hydroxy-pregn-5-ene), cephalostatins/ritterazines (e.g., ritterazines a), miscellaneous steroidal alkaloids (e.g., bufotoxin) (Fig. 15.7 ).

Fig. 15.7.

Basic structure of the steroidal alkaloid nucleus.

15.2.2.8. Imidazole alkaloid (Jin, 2006; Maat and Beyerman, 1984)

The imidazole ring structure is the characteristic of this type of alkaloid. The imidazole ring of these alkaloids is previously made at the stage of the precursor, so they are an exemption in the transformation procedure of structures. This type of alkaloids contains numerous structurally different examples, particularly among marine and microbial alkaloids. They display a wide array of biological activities and significant pharmaceutical potential. Pilocarpine is the most pharmaceutically significant imidazole alkaloid (Fig. 15.8 ).

Fig. 15.8.

Basic structure of the imidazole nucleus.

15.2.2.9. Purine alkaloids (Ashihara et al., 2013; Lean et al., 2011; Rosemeyer, 2004)

Purine is the nitrogenous base of nucleotide (building block of DNA and RNA), which consist of purine ring and pentose sugar along with another base pyrimidine. Caffeine, Theophylline and Theobromine are typical examples of purine alkaloids. They are popular as plant alkaloids, but they can be also originated in marine organisms with substituted purines (e.g., Phidolopin) and a variety of terpenoid-purine alkaloids, such as the age lines and others (Fig. 15.9 ).

Fig. 15.9.

Basic structure of the purine nucleus.

15.2.2.10. Pyrrolidine alkaloids (Cheeke, 1988; Robertson and Stevens, 2014)

Pyrrolidine (C4N skeleton) nucleus constitutes the basic nucleus of pyrrolidine alkaloids. Many pyrrolidine alkaloids are known from plants. Hygrine (biosynthesized from ornithine), ficine (where the pyrrolidine ring is involved to a flavone nucleus), and brevicolline (wherein it is attached to a β-carboline unit) are some examples of this type of alkaloids (Fig. 15.10 ).

Fig. 15.10.

Basic structure of the pyrrolidine nucleus.

15.3. The biological activity of alkaloids

Plant secondary metabolites are a diverse range of biologically active molecules having multiple pharmacological actions like antimicrobial, stimulant, analgesic, anthelmintic, anticoagulant, antiacne, and antioxidant, among others (Debnath et al., 2012; Dey and Bhakta, 2012, Dey and Bhakta, 2013; Dey et al., 2012b, Dey et al., 2013, Dey et al., 2014; Karuna et al., 2018a, Karuna et al., 2018b; Kundu et al., 2019). Different synthetic compounds show potential biological activity in vitro as well as in vivo (Jeon et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2017a, Jeong et al., 2017b; Kim et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018, 2019; Richa et al., 2019; Tae et al., 2018), and various formulations of existing drugs are also developed to increase the safety profile (Gorain et al., 2014; Karmakar et al., 2015; Maity et al., 2016). In spite of this technological development, humans from almost every culture are efficiently employing the plant-derived compounds for the anticipation and management of multiple health disorders for many centuries (Dey et al., 2012a, Dey et al., 2012c).

15.3.1. The biological activity of indole alkaloids

Among all indole alkaloids, reserpine (antihypertensive agent) from Rauvolfia serpentine (Sagi et al., 2016), vinblastine and vincristine (antitumor lead) from Catharanthus roseus (El-Sayed and Verpoorte, 2007) are the most significant. Other indole alkaloids also possess essential and potent pharmacological activities such as antimicrobial, antifungal, CNS stimulant, antiviral. Marine-derived indole alkaloids are very promising and an active group of molecules. They possess various biological activities like antiparasitic, cytotoxic, serotonin and antagonistic realms, antiinflammatory, and antiviral (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

This exclusive type of phytochemicals possesses miscellaneous therapeutic and pharmacological activities which will be discussed in this section.

15.3.1.1. Antimicrobial/antiparasitic activity (Grellier et al., 1999)

Vincristine and vinblastine were isolated from the periwinkle plant C. roseus, also known as V. rosea belongs to the family Apocynaceae and discovered by Robert Noble and Charles Beer of Canada in the 1950s (Anitha, 2016). Trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne disease, which is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi effects in human and other animals. They showed differential effects on the cell division of T. cruzi epimastigote forms in a dose-dependent manner. At a concentration of 50 μM (vincristine) and 15 μM (vinblastine), they avoid both nuclear division and cytokinesis, and also affect cell shape. Whereas at 10 μM (vincristine) and 3 μM (vinblastine) concentration, cytokinesis was repressed without effect on cell-cycle progression. Variations of interactions between microtubules and associated proteins by vincristine and vinblastine may be primarily responsible for the suppression of cytokinesis, rather than from inhibition of microtubule dynamics, which is usually anticipated for these indole alkaloids.

Caboxine A (isolated from air-dried and powdered leaves and bark of Aspidosperma rigidum) had noteworthy antiparasitic activity at a dose of 100 μg/mL and was toxic against Leishmania infantum than T. cruzi with an 82.13% and 69.92% mortality, respectively. Caboxine B was active against T. cruzi with 68.92% mortality of the parasite, while carapanaubine was inactive. None of these compounds were toxic against mammalian CHO cells (Reina et al., 2011).

Reserpine showed potential antimycobacterial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, strain H37Rv, and antioxidant activities. Reserpine displays 55% of growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) at 6.25 μg/mL concentration (Begum et al., 2012).

Halocyamine A inhibited the growth of several Gram-positive bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus cereus, and also the yeast Candida neoformans with a MIC 150, 50, 100, and 100 μg/mL, respectively (Azumi et al., 1990).

Nortopsentins A, B, and C displayed reasonable antifungal activity against Candida albicans (Sakemi and Sun, 1991).

Eudistomin E inhibits the growth of Escherichia coli and Penicillium atrovenetum (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Dragmacidin D introverted the growth of several gram-positive and gram-negative microbes, including E. coli, B. subtilis with MIC values of 15.6 and 3.1 μg/mL, respectively. It also inhibits the growth of several opportunistic yeasts like Candida aeruginosa, C. albicans, and C. neoformans at a MIC of 62.5, 15.6, and 3.9 μg/mL, correspondingly (Wright et al., 1992).

Styelin D exhibited potent antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant and susceptible strain of Staphylococcus aureus. It has also an effect on the outer and inner membranes on E. coli. The penetration into outer membrane by Nitrocefin (a β-lactamase substrate) and inner membrane by o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (a β-galactosidase substrate) is possible after the treatment of Styelin D (Taylor et al., 2000).

Chelonin A exhibited antibacterial activity against the gram-positive bacteria B. subtilis at a concentration of 100 μg/disk (Bobzin and John Faulkner, 1991).

Pibocin B showed potential growth inhibition against B. subtilis, C. albicans, and S. aureus (Makarieva et al., 2001).

Caulerpin inhibits the growth of M. tuberculosis strain, H37Rv at an IC50 of 0.24 μM (Chay et al., 2014).

Vincamine appeared as the most active antibacterial agent against E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, B. subtilis with MIC values between 2 and 8 μg/mL. This compound also having anti-Candida activity at 4 μg/mL (Özçelik et al., 2011).

15.3.1.2. Anticancer activity (Ferguson et al., 1984)

The vinca alkaloids, vincristine, and vinblastine have mostly been used as a chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of cancer. They potentially inhibit the growth of multiple cancer cell lines, like mouse neuroblastoma cells, human leukemia HL-60 cells, HeLa cells, mouse lymphoma S49 cells, mouse leukemia L1210 cells with an IC50 of 33 and 15 nM, 4.1 and 5.3 nM, 1.4 and 2.6 nM, 5 and 3.5 nM, 4.4 and 4.0 nM, respectively. The cytotoxic activity of vinca alkaloids (vincristine and vinblastine) is mainly attributed to the interruption of mitotic spindle assembly via the interaction with tubulin in the microtubules, which comprise the mitotic spindles, and ultimately triggering the metaphase arrest (Gupta et al., 2016; Mohapatra and Mittra, 2016; Seleim et al., 2014; Singh and Prasad, 2014; Sinha, 2014; Abduyeva-Ismayilova, 2016; Thivya et al., 2014). Other biochemical pathways, which are triggered by these alkaloids, may or may not be involved in their influence on microtubules.

In particular, vinca alkaloids bind precisely to the receptor sites on β- tubulin (vincristine binds strongly and intermediate level of binding by vinblastine) and detach it from the colchicine, guanosine-5′-triphosphate, taxanes, and podophyllotoxin. At the end of microtubule, there exist 16–17 high-affinity binding sites and in every mole of tubulin dimer, two vinca alkaloid-binding sites are present. Binding of the vinca alkaloids to the binding sites blocks its capability to polymerize with β-tubulin into microtubules. This enables vinca alkaloids in inhibiting in cell-cycle progression via mitosis and kill actively dividing cells (Creamer and Baucom, 2013; Dang, 2013; Dewir et al., 2014; Pillai and Jayaraj, 2015; Nada et al., 2017; Nomura and Shiina, 2016; Abduyeva-Ismayilova, 2016; Vaidya et al., 2014).

Valparicine, the pentacyclic indole alkaloid of the pericine type, was isolated from a Malayan Kopsia (Lim et al., 2006, Lim et al., 2007). Valparicine was found to exhibit strong cytotoxicity activity toward drug-sensitive and drug-resistant KB cells (KB/VJ300) as well as Jurkat cells with an IC50 of 13.0, 2.72 and 0.91 μM, respectively.

Vallesiachotamine (isolated from the leaves of Palicourea rigida) possesses significant anticancer activity against human (SK-MEL-37) melanoma cells with a possible mechanism of apoptosis. The inhibitory concentration (IC50) against SK-MEL-37 cells was 14.7 ± 1.2 μM for 24 h of drug treatment. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that vallesiachotamine induced cell-cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase and increased the percentage of sub-G1 hypodiploid cells at 11 and 22 μM concentration, and the outcome was not reliant on the time of incubation. Vallesiachotamine at a concentration of 50 μM for 24 h caused extensive cytotoxicity and necrosis (Soares et al., 2012).

The brominated tris-indole alkaloid gelliusine A (isolated from a deep-water new Caledonian sponge). The crude extract of the sponge possesses weak cytotoxic activity against KB, P388, P388/dox, HT29 and NSCLCN6 cell lines (IC50 is 10–20 μg/mL for each test system) (Christopherson, 1985).

The in vitro IC50 of Dragmacidin (isolated from a deep-water marine sponge Dragmacidin sp.) against P-388 cell lines was 15 and 1–10 μg/mL against A-549 (human lung cancer cell lines), HCT-8 (human colon cancer cell lines), and MDA-MB (human mammary cancer cell lines) (Kohmoto et al., 1988; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

A potent antitumor antibiotic Staurosporine [isolated from Streptomyces staurosporeus Awaya (AM-2282)] (Omura et al., 1977). and other actinomycetes, including Streptomyces actuosus and Streptomyces strain M-193) (Oka et al., 1986). possesses high cytotoxic activity against KB and P-388 cancer cell lines with an ED50 value of 0.0024 and < 0.08 μg/mL, respectively (Meksuriyen and Cordell, 1988). It did not hinder the tubulin polymerization or disrupt microtubular function (Gul and Hamann, 2005). Staurosporine also acts as a cytotoxic agent against HT-29 (human colon cancer), MDA-MB-231 (human breast cancer), and A549 (human lung cancer) at GI50 values of 10.9, 7.1, and 2.4 nM, respectively (Reyes et al., 2008).

Eudistomin K (isolated from Caribbean ascidian Eudistoma olivaceum) is an indole alkaloid, which contains a novel oxathiazepine ring, and is found to be an antitumor lead against L-1210, A-549, HCT-8, and P-388 cell lines. The in vitro IC50 value of this compound was 0.01 μg/mL against P-388 cell line (Lake et al., 1989; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Grossularine 1 and 2 (isolated from isolated from the tunicate Dendrodoa grossularia) (Moquin-Pattey and Guyot, 1989) possess potent cytotoxic activity against L-1210 cancer cell line with IC50 values of 6 and 4 μg/mL, respectively, and also of IC50 values of < 0.01 μg/mL against WiDr (colon cancer cell line) and MCF7 (breast cancer cell line) (Moquin-Pattey and Guyot, 1989). Grossularine 1 and 2 act as a monointercalating agent of DNA and also accumulate the cell in G1 phase at a concentration of 10 and 1.5 μg/mL, respectively (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Halocyamine A (isolated from the solitary ascidian Halocynthia roretzi) (Azumi et al., 1990; Gul and Hamann, 2005) was found cytotoxic at a concentration of 160 μM for 24 h against neuroblastoma N-18 cells. Halocyamine A also causes deterioration of the neurite at a concentration of 100 μM against neuronal cells cultured from rat fetal brain. The cytotoxic activity of halocyamine A was also proved against HepG2 cancer cell line at a concentration of 200 μM for 24 h.

Topsentin (isolated from the Caribbean deep-sea sponge Spongosorites ruetzleri) possesses in vitro activity cytotoxic activity against P-388 with an IC50 3.0 and 20 μg/mL for human tumor cells (HCT-8, A-549, and T47D). The compound also shows in vivo antitumor activity against P-388 (T/C 137%) and B16 melanoma (T/C 144%) at a concentration of 150 mg/kg and 37.5 mg/kg, respectively (Tsujii et al., 1988; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Hyrtiosins A and B (isolated from the Okinawan sponge Hyrtios erecta) exhibited cytotoxic activities higher than 5-hydroxyindole-3-aldehyde, whose IC50 was reported to be 4.3 μg/mL against in vitro against human epidermoid carcinoma KB cells (Kobayashi et al., 1990; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Nortopsentins A, B, and C (isolated from the Caribbean deep-sea sponge S. ruetzleri) act as cytotoxic compounds against P-388 cells with IC50 values of 7.6, 7.8, and 1.7 μg/mL, respectively (Sakemi and Sun, 1991; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Eudistomin E and Eudistalbin A (extracted from the marine tunicate Eudistoma album) possess in vitro cytotoxic activities with ED50 < 0.005 and 3.2 μg/mL, respectively, against KB cells (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Dragmacidin D, a bis (indole)-derived sponge metabolite, (isolated from the sponge Spongosorites sp. Dragmacidin D) exhibits in vitro anticancer activity against P-388 and A-549 with IC50 values of 1.4 and 4.4 μg/mL, respectively (Gul and Hamann, 2005; Wright et al., 1992).

Makaluvamine G (isolated from the Indonesian sponge Histodermella sp.) displayed cytotoxic activity with IC50 values of 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, and 0.4 μg/mL against P-388, A-549, HT-29, MCF-7 and KB, respectively (Carney et al., 1993; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Gelliusines A and B (isolated from a deep-water New Caledonian sponge Gellius or Orina sp.) (Bifulco et al., 1994) showed anticancer activity against KB, P-388, P-388/dox, HT-29, and NSCLCN-6 cell lines with IC50 values of between 10 and 20 μg/mL (Bifulco et al., 1994; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Konbamidin is an indole alkaloid (isolated from the Okinawan marine sponge Ircinia sp.) displayed in vitro cytotoxicity against Hela cells with an IC50 value of 5.4 μg/mL (Shinonaga et al., 1994; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

A peptide, Kapakahine B (isolated from the marine sponge Cribrochalina olemda) (Nakao et al., 1995), showed reasonable anticancer activity against P-388 murine leukemia cells with an IC50 value of 5.0 μg/mL (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Another unique peptide Styelin D (isolated from the hemocytes of the solitary ascidian Styela clava) demonstrated anticancer activity against HCT-116 and human ME-180 cervical epithelial cells with an IC50 value of 10.1 μg/mL and ED50 value of 50 μg/mL, respectively (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Topsentin B1 and B2 (isolated from the Mediterranean marine sponge Rhaphisia lacazei) inhibited NSCLC-N6 (human bronchopulmonary cancer cells) with IC50 values of 12.0 and 6.3 μg/mL, respectively (Casapullo et al., 2000; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Pibocin B (isolated from the ascidian Eudistoma sp.) showed cytotoxic activity against mouse Ehrlich carcinoma cells with an ED50 value of 25 μg/mL (Makarieva et al., 2001; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Convolutamydine A (isolated from marine bryozoan Amathia convolute) showed significant anticancer activity against HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia cells). At a concentration of 0.1–25 μg/mL, this indole alkaloid brings a change in culture plate adhesion, induces growth arrest, and phagocytosis (Gul and Hamann, 2005; Kamano et al., 1995).

Manzamine B, E, and F (collected from various sponges, including an Amphimedon sp.) have been presented with cytotoxic activity against P-388 murine leukemia cells with an IC50 values of 6.0, 5.0, and 5.0 μg/mL, respectively (Hu et al., 2003b; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Echinosulfonic acid D (isolated from the New-Caledonian sponge Psammoclemma sp.) (Ovenden and Capon, 1999) was found to be cytotoxic at an IC50 of 2 mg/mL to KB cells (Rubnov et al., 2005).

15.3.1.3. Antiangiogenesis effect

At concentrations of 0.1–1.0 pmol/L, vinblastine blocks endothelial proliferation, chemotaxis, and spreading on fibronectin without affecting other fibroblasts and lymphoid tumors (Amalraj et al., 2013; Freire et al., 2013; Malafaia et al., 2013; Mishra and Prasad, 2016; Reggia et al., 2016; Srivastava and Sharma, 2014; Shi et al., 2013; Sudhir Kumar et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2013b). A combination of low doses of vinblastine and antibodies against VGFR (vascular endothelial growth factor) upturns the antitumor effect of the drug even in resistant tumors also (Anitha, 2016).

15.3.1.4. Antioxidant activities (Begum et al., 2012)

In the DPPH radical-scavenging assay, it was found that reserpine possesses 42% inhibition of DPPH radical.

Lind et al. performed two different biochemical assays, FRAP (Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power) and ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity), to find the antioxidant activity of barettin. According to their experiment, barettin showed a potential antioxidant profile in a dose-dependent manner. At a concentration of 30 μg/mL barettin had FRAP and ORAC values of 77 and 5.5 μM Trolox equivalents (TE), respectively (Lind et al., 2013).

15.3.1.5. Antihypertensive activities

Reserpine is highly used as a first-line therapeutic agent in reducing blood pressure in primary hypertension. A dose of reserpine 0.5 mg/day or greater attained the statistically significant SBP (systolic blood pressure) effects (Shamon and Perez, 2016). The underlying mechanism of the antihypertensive action of reserpine is, it reduces the catecholamines concentration from the peripheral sympathetic nerve endings. Reserpine has the higher affinity for VMAT2 (vesicular monoamine transporter), irreversibly binds to their receptors, and irrevocably blocks the VMAT2 (Schuldiner et al., 1993). VMATS is responsible for the transportation of released and free nor-adrenaline or nor-epinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin (5-HT) from the cytoplasm of the presynaptic nerve terminal into storage vesicles for further release into the synaptic cleft (Blackman et al., 1959; Nammi et al., 2005). Due to uptake obstruction, these unshielded and susceptible neurotransmitters never reach the synapse to exert their actions as they are metabolized by COMT (catecholamine-o-methyl transferase) and MAO (monoamine oxidase) in the cytoplasm. Reserpine has the higher affinity for VMAT2 and binds irreversibly to their receptors. It is a potent antihypertensive agent and tranquilizer, but its sustained usage stimulates the release of prolactin and causes breast cancer (Meenakshi and Priyanka, 2010).

15.3.1.6. Treatment for antidyskinesia syndromes (Shen, 2008) and others (Singh, 2017a)

Formerly reserpine was used to treat indications of dyskinesia in patients suffering from Huntington’s disease. Reserpine is also used in various psychiatric diseases by acting as a tranquilizing agent.

15.3.1.7. Settlement inhibition of barnacle larvae or antifouling agents

Barettin (cyclo[(6-bromo-8-entryptophan)arginine]) and 8,9-dihydrobarettin (cyclo[(6-bromotryptophan)arginine]) are brominated cyclodipeptides, which has been isolated from a marine sponge Geodia barrette family Geodiidae. These two compounds, barettin and 8,9-dihydrobarettin, intensely prevent the settlement of the barnacle larva of Balanus improvisus and the blue mussel Mytilus edulis in a dose-dependent manner in concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 25 μM with EC50 values of 0.9 and 7.9 μM for barettin and 8,9-dihydrobarettin, respectively (Sjögren et al., 2004a, Sjögren et al., 2004b).

15.3.1.8. Interaction with human serotonin receptors

Barettin especially interacted with the three different serotonin receptors 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT4 at approximately similar concentrations that of endogenous serotonin, with the K i values 1.93, 0.34, and 1.91 μM, respectively. This is possible because of the structural resemblance between tryptophan residue and the endogenous serotonin (Erik et al., 2006). On the other hand, 8,9-dihydrobarettin interacted with only 5-HT2C receptor with a K i value of 4.63 μM (Erik et al., 2006).

Gelliusine A was acting as a restricted agonist for serotonin receptor(s). At lower concentration, this compound blocks the serotoninergic receptor(s) by acting as a serotonin antagonist, which was confirmed by experimenting on male guinea pig ileum; however, at higher concentration (5–70 μg/mL), it was responsible for serotonin-like and methysergide-sensitive contraction. This result recommends the possible role of gelliusine A as a serotoninergic system modulator (Bifulco et al., 1994; Christopherson, 1985).

15.3.1.9. Antinociceptive and antiinflammatory activities

Barettin was also able to inhibit the secretion of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα from LPS-stimulated human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 cells (Lind et al., 2013).

Dragmacidin has shown to have antiinflammatory activity by inactivating the bee venom PLA2 (in vitro assay) and mouse ear edema test (in vivo assays) (Jiang et al., 1994).

Chelonin A (isolated from the sponge Chelonaplysilla sp.) displayed potential antiinflammatory activity by inhibiting 60% PMA-induced inflammation in a mouse ear model at a concentration of 50 μg/ear (Bobzin and John Faulkner, 1991; Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Caulerpin (isolated and purified from the lipid extract of Caulerpa racemose) (Lunagariya et al., 2017) possesses comparable analgesic activity (0.0945 μmol) in contrast to dypirone (0.0426 μmol) by reducing acetic-acid-induced nociception in the abdominal constriction test. In the hot plate test also, caulerpin inhibits the nociception in vivo at a dose of 100 μmol/kg, p.o., which proves caulerpin shows a central activity, without altering the motor action. Caulerpin, at a dose of 100 μmol/kg, p.o. inhibits the inflammation by 55.8% in capsaicin-induced ear edema model. The promising antiinflammatory activity was also detected after the reduction of the number of recruit cells by 48.3% significantly at a dose of 100 μmol/kg, p.o. in the carrageenan-induced peritonitis model (de Souza et al., 2009).

15.3.1.10. Immunomodulatory effects (Lind et al., 2015)

Lind et al. showed that barettin obstructs two inflammatory protein kinases, receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 (RIPK2) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 1α (CAMK1α). According to them, barettin possibly inhibits CAMK1α, which ultimately results in inhibition of antiinflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) production in a dose- and time-dependent manner. It also diminishes the excretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) from immune cells. All these highlight the atheroprotective effect of barettin.

15.3.1.11. Anticoagulant activities

Tissue factor (TF), the transmembrane glycoprotein, is a major stimulator of blood coagulation, which is synthesized by monocyte (Osterud and Bjorklid, 2012). It binds with Factor VII and forms a complex TF-FVII complex, which in turn activates Factors IX and X, and subsequently generates thrombin, as well as activates platelet and fibrin deposition (Mann et al., 2006). Apart from the role of coagulation, this TF-factor VII complex is also involved in other pathophysiological roles like atherosclerosis, tumor metastasis, inflammation, and angiogenesis (Åberg and Siegbahn, 2013; Schaffner et al., 2012). Barettin acts in this pathway and acts as a potent anticoagulant (Lind, 2015).

15.3.1.12. Antiviral activity

Eudistomin K inhibits the growth of HSV-1 (Herpes simplex virus) at a concentration of 0.25 and 0.10 μg/disk, respectively (Rinehart Jr et al., 1987).

Topsentin exhibited in vitro antiviral activity against HSV-1, VSV (Vesicular stomatitis virus), and the corona virus A-59 (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Eudistomin E possesses antiviral activity against both DNA (e.g., HSV-1, 2 and vaccinia virus) and RNA viruses (such as Coxsackievirus A-21 and equine rhinovirus) (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

Dragmacidin D showed in vitro antiviral activity by repressing the replication of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) at an IC50 of 6.25 μg/mL (Wright et al., 1992).

The alpha and beta phases are very essential where factors responsible for the regulation of viral replication, antigenic presentation, and genome replication are synthesized. Caulerpin inhibits the alpha and beta phases of the replication cycle. Hence, it can be used as a substitute to acyclovir as an anti-HSV-1 drug (Macedo et al., 2012).

15.3.1.13. Enzyme inhibitor

Dragmacidin D inhibits serine-threonine protein phosphatases. It also inhibits the activity of neural nitric oxide synthase (βNOS), which may corroborate to help in Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s disease treatments (Yang et al., 2002).

15.3.1.14. Antitopoisomerase-I activity

Makaluvamine G possesses moderate inhibitory activity against topoisomerase-I (IC50 3.0 μM). It also inhibits the activity of DNA, and protein at an IC50 of 15, 15, and 21 μM (Carney et al., 1993).

15.3.1.15. Calmodulin-antagonistic activity

Eudistomidin A was isolated from the Okinawan tunicate Eudistoma glaucus (Kobayashi et al., 1986). This alkaloid was the first calmodulin antagonist reported from a marine source. The IC50 (2 × 10− 5 M) of eudistomidin A was 15 times more potent than W-7 (3 × 10− 4 M), a well-known calmodulin antagonist, used against calmodulin-activated brain phosphodiesterase (Gul and Hamann, 2005).

15.3.1.16. Plant growth regulator

Caulerpin is the first plant growth regulator isolated from marine origin. This bis-indole alkaloid possesses excellent root growth and development promotion activity equivalent to indole-3-pyruvic acid and indole-3-acrylic acid (Raub et al., 1987).

15.3.1.17. Antidiabetic and antiobesity activity (Mao et al., 2006)

Type II diabetes and obesity have emerged as a worldwide health issue. Human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (hPTP1B) is one of the important enzymes, which hydrolyze phosphotyrosines on the insulin receptor, hence deactivating it. So, hPTP1B is considered a strategic target to tackle these two diseases. Caulerpin displayed potent hPTP1B inhibitory activity at an IC50 value of 3.77 μM.

15.3.1.18. Spasmolytic effect (Cavalcante-Silva et al., 2013)

Caulerpin exhibits the spasmolytic effect on guinea pig ileum. This bis-indole alkaloid inhibited phasic contractions induced by carbachol, histamine, and serotonin in a nonselective manner. Caulerpin marginally repressed the CaCl2-encouraged contractions in depolarizing medium without Ca2 +, and hence shifting the curves to the right and with E max reduction. So, this attributes the mechanism of this spasmolytic effect of caulerpin as it inhibits the Ca2 + influx via voltage-gated calcium channels (Cav).

15.3.1.19. Effect on central nervous system and brain (Borzeix and Cahn, 1984)

Vincamine, the common nitrogen-based secondary metabolites, comprise one or more indole/indoline moieties. This was first isolated from Vinca Minor L (Periwinkle) and belongs to the apocynaceae family. In male Wistar rats, vincamine ketoglutarate, vincamine teproside, and vincamine hydrochloride prohibited the manifestation of cerebral edema and inhibited the neurological insufficiency caused by the administration of triethyltin hydrochloride.

15.3.1.20. Other imperative medicinal uses of indole alkaloids (Dhayalan et al., 2015; Jordan and Wilson, 2004)

The cotreatment of vinblastine along with bleomycin and methotrexate in VBM chemotherapy for Stage IA or IIA Hodgkin lymphomas was found markedly effective. Likewise, this alkaloid was also used for the subsequent treatments like mycosis fungicides, testicular cancer, Letterer-Siwe disease, Hodgkin’s sickness, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, Kaposi’s sarcoma related to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), etc.

Vincristine is administered through intravenous infusion for several categories of a therapeutic regime. As a part of the chemotherapeutic regime, this alkaloid is used against non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Vincristine is sporadically used as an immunosuppressant, for example, in case of treating thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. For the treatment of childhood leukemia, vincristine is used in combination with prednisone. This alkaloid is also used for the therapeutic application of many diseases like idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, bladder cancer, cervical cancer, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, neck cancer, and head cancer (Dhayalan et al., 2015; Qweider et al., 2007).

15.3.2. The biological activity of tropane alkaloid

15.3.2.1. Effect on asthma

Atropine is isolated from dried leaves and flowering tops of Datura metal of Solanaceae family.

It has an action against Nocturnal Asthma. Nocturnal asthma can be effectively treated by atropine methyl nitrate (Sur et al., 1990), atropine sulfate (Owens and George, 1991), and atropine in blended with metaproterenol (Young and Freitas, 1991) and albuterol, correspondingly. In humans, lung mucociliary function can be improved by inhalation of atropine (Groth et al., 1991).

15.3.2.2. Protection against organophosphorus compounds

Toxic effect of organophosphate can be neutralized by atropine only and with cholinesterase reactivator (Ligtenstein and Moes, 1991; Romano et al., 1991). A combination of clonidine (Wu-Fu, 1991) and diazepam (Tsung-Ming, 1991) was also found active with atropine sulfate.

Scopolamine exerts a protective effect against Organophosphate Exposure (Solana et al., 1991). In vivo muscarinic cholinergic receptor imaging, besides through positron emission tomography, can be done by using C-scopolamine (Frey et al., 1992).

15.3.2.3. Activity against hyperglycemia and parkinsonism

Atropine suppresses neostigmine-induced hyperglycemia (Iguchi et al., 1991). Atropine influences the vagal tone of diabetic patients (Julu et al., 1991). Tremor in parkinsonism of a monkey model can be reposed by atropine (Gomez-Mancilla et al., 1991).

Hyoscine antagonizes the cholinergic activity at the muscarinic receptors in the striatum and increases DA activity, hence used to treat PD (Houghton and Howes, 2008).

15.3.2.4. Effect on ANS (Fodor and Dharanipragada, 1994)

Atropine acts as a competitive antagonist of the activities of acetylcholine and other muscarinic agonists. It also contests for a mutual binding site on all muscarinic receptors. Atropine blocks the muscarinic receptors in smooth and ganglia and intramural neurons.

15.3.2.5. Effect on CVS (Fodor and Dharanipragada, 1994)

Atropine blocks the muscarinic receptors in cardiac muscle. It also used in cardiac dysfunction.

15.3.2.6. DNA protectant and mitotic inhibitor

Colchicine is a strong spindle fiber poison and inhibits the polymerization of tubulin (Foye, 1995).

15.3.2.7. Anticancer and antiinflammatory activity

At toxic or nearly toxic dosage, colchicine is effective against chronic myelocytic leukemia and gout (Wedge and Camper, 1999).

15.3.2.8. Use against nausea, drooling, and Alzheimer disease

Scopolamine is applied to get rid of nausea and drooling in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Postoperative nausea and vomiting of morphine can be minimized by transdermal application of scopolamine (Horimoto et al., 1991). Transdermal scopolamine was used as nausea prophylaxis (Harris et al., 1991) and against drooling (Dreyfuss et al., 1991; Siegel and Klingbeil, 1991). Scopolamine has an impact on environmentally induced pain reactivity (Grau et al., 1991).

15.3.2.9. For treating motion sickness

The complication of motion sickness is overcome by the use of transdermal scopolamine. When applied behind the ear 5 h erstwhile to sailing, this drug is found effective in inhibiting seasickness (Attias et al., 1987).

15.3.2.10. Antispasmodic and antiallergic effects

Hyoscyamine and atropine contribute antispasmodic and antiallergic effects by acting as a competitive antagonist at the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor site (Kinghorn, 2001; Sneader, 2005).

15.3.2.11. Hyperactivity: Effect on slowing

In mice, scopolamine-activated hyperactivity is shared by the cholinergic and dopaminergic representatives (Shannon and Peters, 1990). Riekkinen and Valjakka et al. mentioned the effects of tetrahydroaminoacridine (THA, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor) on scopolamine-induced neocortical spectral electroencephalography (EEG) slowing (Riekkinen Jr et al., 1991; Valjakka et al., 1991). Acetylcholine synthesis in the brain was marked affected by scopolamine, oxotremorine, and physostigmine (Bertrand and Beley, 1990).

15.3.2.12. Central sedative, antiemetic, and amnestic effects (Renner et al., 2005)

Scopolamine is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist. The mechanism of action of the anticholinergic drug scopolamine includes the competitive antagonism of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptors (M1). This blockage of acetylcholine inhibits the acetylcholine-mediated nerve impulse from traveling throughout the body. This antimuscarinic property allows scopolamine to produce the central sedative, antiemetic, and amnestic effects.

15.3.2.13. Miscellaneous

Atropine has an influence on the pelvic pouch and anal sphincter functions (Hallgren et al., 1991). Atropine impacts radial arm maze enactment of the rat when centrally administered (Sala et al., 1991).

15.3.3. The biological activity of isoquinoline alkaloids

15.3.3.1. Effect against neurodegenerative diseases

Berberine is one of the important isoquinoline alkaloids. It is present in medicinal plants, especially in the genus Berberis like Berberis vulgaris. Berberine is potentially effective against multineurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases (Ahamad et al., 1969).

15.3.3.2. Antibacterial activity (Peng et al., 2015)

At minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) of 78 μg/mL, berberine shows antibacterial activity by severely damaging bacterial cell membrane structure by inhibiting cellular proteins, which were confirmed by TEM and SDS-PAGE. This compound altered bacterial DNA synthesis. It also hinders the biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in a concentration-dependent manner ranging from 1 to 64 μg/mL via inhibiting phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) aggregation into amyloid fibrils (Chu et al., 2016).

15.3.3.3. Anticancer activity

Berberine inhibits the cancer cells keratinocytes at an IC50 of 30 μmol/L (Müller et al., 1995). It also reduces the entwined sarcoma in an animal by 0%, 53%, and 33 % at the doses of 5, 2.5, and 0.5, mg/kg, respectively (Anis et al., 2001). In vitro antiproliferative activity of berberine is also achieved against HeLa cells, Dalton lymphoma of ascitic cancer cells, and L929 cells at an IC50 of 7.2, > 1000, and 40 mg/L, respectively (Anis et al., 1999).

Emetine shows cytotoxicity by apoptotic mechanism in various cancer cell lines: at EC50 of 0.05 μM against CCRF-CEM (Human T-cell lymphoblast-like cell line) (Meijerman et al., 1999), at LD50 of 55 μg/mL against A549-S (lung adenocarcinoma) (Watanabe et al., 2002), at EC50 of 2 μM against CEM/ADR5000 (leukemia cell line) (Möller et al., 2006), at EC50 of 0.17 μM against Jurkat T cells (T-cell leukemia) (Möller et al., 2006). Emetine inhibits the protein synthesis and interacts with DNA and exerts its cytotoxic activity (Grollman, 1968). In PC3 (prostate cancer cell line), MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line) emetine significantly decreases the ratio of BCL-xS/BCL-xL (Boon-Unge et al., 2007). Treatment with emetine in Jurkat cells results in downregulation of EGFR, BCL2, TNF and upregulation of the TNFRS11B, AKT1, TNFSF13, Caspase 8, TNFRSF6, BAK1, caspase 9, MST1, GZMB, DAXX (Möller et al., 2007).

15.3.3.4. Antidiabetic activity

Berberine (methanolic extract) shows its antidiabetic potential at the dose of 500 mg/kg. Not only antidiabetic activity, but also Berberis aristata (methanolic extract) show its potential effect on carbohydrate metabolism as well as HDL and cholesterol levels (Saravanan and Pari, 2003; Yadav et al., 2005).

15.3.3.5. Antiosteoporosis activity

Berberine shows mild laxative as well as hypocholesterolemic activity (Chauhan, 1999). Berberine and its methanolic extract displays significant antiosteoporosis activity and substantiates the ethnic use in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (Potdar et al., 2012; Yogesh et al., 2011).

15.3.3.6. Treatment in cardiovascular diseases

In cardiovascular diseases, berberine compound is used as an antihyperlipidemic agent. After the administration of berberine, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and cholesterol content were reduced by 25%, 35%, and 29% within three months, respectively (Kong et al., 2004; Shenoy and Yoganarasimhan, 2009).

15.3.3.7. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity (Li et al., 2014)

Berberine inhibits the oxidative stress and inflammation in various tissues, including liver, kidney, pancreas, and adipose tissue by targeting various signaling pathways and cellular kinases like mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, AMPactivated protein kinase (AMPK), and nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) pathway.

15.3.3.8. MAO inhibitor and others

Berberine moderately inhibits the monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme, K i = 110 μmol/L, IC50 = 126 μmol/L (Kong et al., 2001). Berberine also has antidiarrheal, antifungal, and antiprotozoal activity. Currently, research indicates that berberine shows its protective mechanism against atherosclerosis. Tincture of the root of berberine is better than quinine and cinchona in the treatment of intermittent fever because it does not produce cardiac depression (Chatterjee and Pakrashi, 1991).

15.3.3.9. Antiviral activity

Psychotria ipecacuanha Stokes (Rubiaceae) is one of the major sources of Emetine. This isoquinoline alkaloid mainly occurs in three plant families comprising Icacinaceae, Rubiaceae, and Alangiaceae. The main active constituent of ipecac root is emetine (Wiegrebe et al., 1984). Possessing vital biological functions to make emetine is a major constituent to molecular biologists and pharmacologists.

Emetine shows antipoxviral activity by inhibiting vaccinia virus replication at noncytotoxic doses (inhibition of plaque at 0.25 μM; IC99: 0.1 μM for 48 h) (Deng et al., 2007). Antiviral activity against four serotypes of dengue virus (DENV) at an early stage has also been reported in a dose-dependent manner at a noncytotoxic dose by affecting viral replication cycle either by disturbing viral protein translation pathway or damaging viral RNA synthesis pathway (Yin Low et al., 2009). At a dose of 0.1 μM, DENV II was repressed by 33%, while 90% inhibition was observed at 0.5 μM to 10 μM dose (Yin Low et al., 2009).

15.3.3.10. Contraceptive activity

Emetine is used as a contraceptive agent in the rabbit uterus and it shows an antiimplantation effect in a concentration-dependent manner (Moyer et al., 1977). Another research study on five rodent species: hamster, rat, mouse, guinea pig, and rabbit via oral and intravaginal routes demonstrated the prospective use of emetine ditartrate as an alternative contraceptive agent (Mehrotra et al., 2004). The main site of action of emetine ditartrate includes uterus and primary embryos nearby implantation, probably the trophoblast and endometrial cells at the addition site.

15.3.3.11. Antiparasitic activity and others

Emetine inhibits the growth of Entamoeba histolytica responsible for amoebiasis and amebic dysentery (Lambert, 1918; Thompson, 1913; Vedder, 1912). Hence, it is effective in the treatment of perianal skin amoebiasis and amoebic liver (Hughes and Petri Jr, 2000; Ruiz-Moreno, 1967). Emetine induces programmed cell death in this same parasite and induces nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation, and inhibits the maintenance of cell membrane integrity (Villalba-Magdaleno et al., 2007).

Emetine is also effective against leishmaniasis by inhibiting Leishmania donavani (Muhammad et al., 2003). Emetine also inhibits the protein biosynthesis and induces DNA fragmentation in Trypanosoma b. brucei (Rosenkranz and Wink, 2008). It also possesses anthelmintic activity in infected goat and sheep at a dose of 1 mg/kg against Protostrongylus rufescens (Akinboye and Bakare, 2011; Shahlapour et al., 1970). Emetine interferes with the function of alcohol dehydrogenase and therefore alters the pathological function of alcohol addiction (Nikolaenko, 2001).

15.3.3.12. Miscellaneous

The mechanistic approach of codeine includes K+ conductance (opening of IC channels) with neurons responding via hyperpolarization. A reduction of the Ca2 + entry into nerve termini (closing of voltage-gated Ca2 + channels) consequently prevents the secretion of excitatory neurotransmitters and synaptic activity. Such types of inhibitory effects on synaptic cleft may produce either a depressant or an excitant effect. Opioid alkaloids, especially morphine and other narcotic agents, have produced their pharmacological effect through mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (δ) receptors (Fries, 1995; Gutstein and Akil, 2001; Lüllmann et al., 2000).

The primary effect of these opium alkaloids (morphine and codeine) and morphine-like narcotic antagonists in CNS involves analgesia, drowsiness, euphoria, a sense of detachment, respiratory depression, depressed cough reflex (partially via direct action on the medullary cough center), and hypothermia. These types of alkaloids also act on the parasympathetic nervous system, and the specially oculomotor nucleus is responsible for pupillary miosis.

The other effects of these opium alkaloids (morphine and codeine) include reduced gastrointestinal motility, increased resting tone and spasm, and increased anal sphincter tone. The major therapeutic action of morphine is relief from mild or severe pain. It is also used as an anesthetic intraoperative cases. Sometimes, morphine is applied for acute pulmonary edema due to the presence of the hemodynamic property (Fries, 1995; Gutstein and Akil, 2001).

Thebaine has a stimulatory effect on the central nervous system. It produces hyperirritability and motor activity on animal model, especially in mouse, rabbit, cat, and dog, at doses around 2–10 mg/kg s.c. or i.m. Many published reports suggest that thebaine upsurges gastrointestinal tone and intestinal activity.

Papaverine has smooth-muscle relaxant property. The smooth musculature of the larger blood vessels is relaxed, including the coronary, systemic peripheral, and pulmonary arteries. The vasodilation effect of papaverine has been credited to inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, with resulting rises in intracellular levels of the cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accompanied by declines in Ca2 +. This alkaloid produces prolonged myocardial refractory period by decreasing the conduction rate (Cocolas, 1982; Lindner, 1985; Schmeller and Wink, 1998). This alkaloid is often used as a topical gel in sexual dysfunction in order to obtain an erection in patients with spinal cord injuries. Due to the presence of the above property, this alkaloid got Orphan Drug status.

Noscapine possesses analgesic properties. It also has antitussive activity equal to that of codeine. That is why the name was changed to noscapine. Besides noscapine with small doses also showed a bronchodilatory effect. A large dose of noscapine produces bronchoconstriction and transient hypotension due to secretion of histamine (Abd-Rabbo, 1969; Grollman, 1968; Schmeller and Wink, 1998).

The application of curare is very less except as a source of alkaloids. The commercial product such as Tubocurarine chloride is used as a muscle relaxant in the surgical case and neurological disorder (Dewick, 2002; Willette, 1998).

15.4. Techniques of extraction, purification

Generally, extraction is the first step to separate the compounds from the mixture of solid or liquids by a suitable solvent (Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001; Huie, 2002b). Moreover, extraction is also the preliminary step in the drug discovery process and developments in the indole, isoquinoline, and tropane groups of plants. Many procedures have been established to obtain extracts showing a range of polarities and augmented widespread secondary metabolites such as alkaloids. There is a wide range of well-established techniques to extract alkaloids such as maceration, infusion, decoction and boiling under reflux, microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), and pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) (Table 15.3 ).

Table 15.3.

Different types of extraction processes.

| Type | Sample size; solvent | Temperature | Pressure/time | Investment | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet | 1–2000 g; 4–8000 mL | Depends upon the solvent | Atmospheric/6–8 h | Very low | Efficient for polar and nonpolar BAC |

| SFE | 25–100 g; continuous flow | – | 25–45 MPa; 1–2 h | High | Efficient for nonpolar BAC |

| PLE | 1–30 g; 10–100 mL | 80–200°C | 1–10 MPa; 10–30 min | High | Efficient for polar and nonpolar BAC, Safety |

| MAE | 1–20 g; 10–50 mL | 80–150°C | Variable/10–30 min | Moderate | Use of solvents is risky |

| Hydro distillation | 10–100 g | 40–60°C | Atmospheric/6–8 h | Low | Residual hydrotropic |

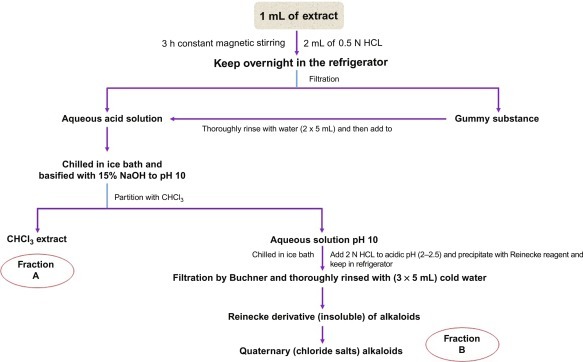

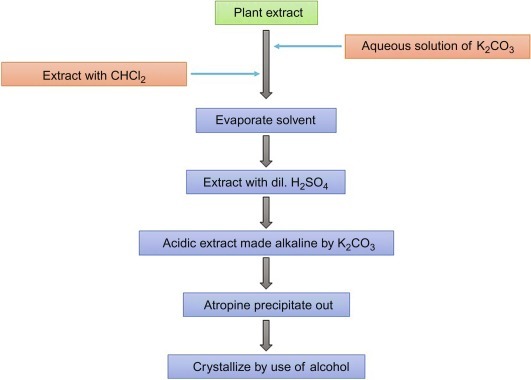

Fig. 15.11 describe the general flowchart of alkaloid extraction and purification.

Fig. 15.11.

General techniques of alkaloid extraction.

15.4.1. Mechanical methods

Mortar and pestle, grinding mill, and mixer grinder are generally used for grounding plant tissues before extraction. For instance, lignified plant material was frozen and pulverized with liquid nitrogen in a mortar and pestle (Kirakosyan et al., 2016). Sonicator was also used for extraction of plant products grown by cell suspension culture methods (Bhargavi et al., 2018).

15.4.2. Chemical degradation

Various types of potential chemicals are used for breaking down of cell walls. The insoluble matrix, as well as the molecular structure of the cell wall, can be disrupted by detergents. For example, Triton X-100, octyl glycoside, and Tween-20 are some of the nonionic detergents. Ionic detergents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) are used for the aforementioned purposes (Bhargavi et al., 2018; Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001; Huie, 2002b).

15.4.3. Precautions to be taken during extraction processes

Compounds may be destroyed by the presence of excessive heat, certain chemicals, enzymatic reaction inside the cell. In the case of water-soluble materials, one needs to be aware of the buffer system. Due to methodical error in the extraction technique as well as isolation process, polyphenols may be deactivated by insoluble polyvinyl polypyrrolidine (PVPP), soluble polyvinyl pyrrolidine (PVP). A chelating agent such as EDTA may be added to eliminate divalent cations from the extracts. Foams are suppressed by using suitable antifoaming agents such as DC-544 (Dow Corning) or SAG-30 (Union Carbide) (Bhargavi et al., 2018; Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001; Huie, 2002b).

15.4.4. Extraction with solvents (liquid-liquid extraction or solid-liquid extraction)

The homogenized cell is kept in the extracting solvent for a certain time so that all parts of the cells are easily penetrated by the solvent. The main primary key of the extraction process is to find out the suitable solvent and effect of temperature. An ideal extraction method should avoid some important phenomena associated with physical incompatibility. These important phenomena include decomposition, isomerization, or polymerization. Another important parameter is compound stability. The stability of the compound depends on light, heat, and solvent polarity. Extraction is a separation technique of the desired compound from a matrix as in the case of soxhlet extraction and countercurrent extraction (Bhargavi et al., 2018; Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001; Huie, 2002b; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014).

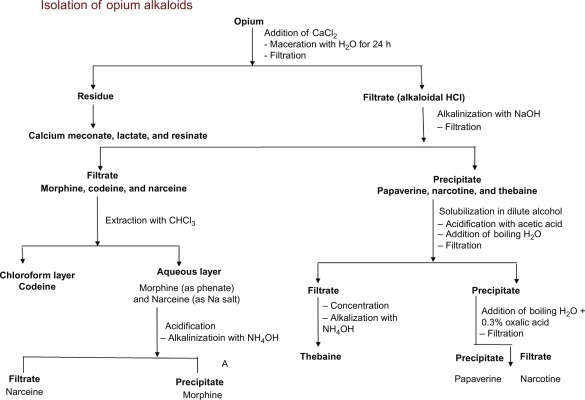

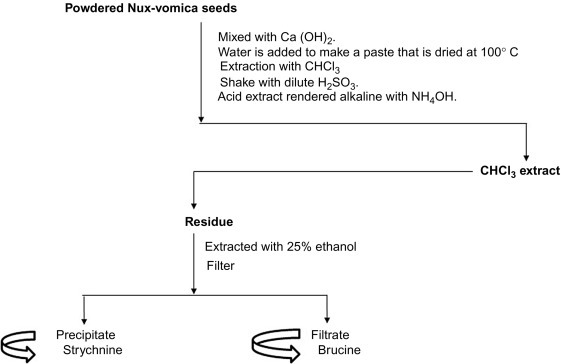

Fig. 15.12 describes the isolation techniques of opium alkaloids (isoquinoline).

Fig. 15.12.

Extraction and purification techniques of opium alkaloids.

An ideal solvent dissolves the desired compound, leaving the other constituents.

Polarity index is a golden standard of measurement of the intensity of interaction of the solvent with various polar solutes. For extraction of the nonpolar compounds, nonpolar solvents are applied. Hexane is used for extraction of fixed oil, chlorophylls, steroids, and terpenoids. Highly polar compounds such as glycosides, sugars, amino acids, proteins, and polysaccharides can be extracted with polar solvents. Less polar compounds such as isoflavones, flavanones, methylated flavones, and flavonols are extracted with low polar solvents such as chloroform, dichloromethane, diethyl ether, or ethyl acetate; and the polar flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides are extracted with alcohols or aqueous alcohol mixtures (Barnes, 1999; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014; Patil et al., 2012).

Volatility is a major drawback of a compound during the extraction process. Such type of problem may be overcome by using solvents with a low boiling point without denaturation at high temperature.

The solvent selection is necessary for better extraction technique. By modification, the solvent becomes more acidic and more basic in certain extraction processes. Acidified solvents are mainly used for alkaloid extraction, whereas the basic nature of a certain solvent is applied for phenolic compounds. Generally, 5% HCl is applied for the alkaloids extraction, amines, and pyrazines, 5% NaOH or 5% KOH preferentially extracts phenolics compounds. For extraction of catechins, methanol is used as an ideal solvent. For procyanidins, 70% acetone is used. In the case of anthocyanins extraction, a slight acidic solvent is selected and thus 0.1% HCl in methanol is used. 7% acetic acid or 3% trifluoroacetic acid has been also used for the extraction of anthocyanins. Acyl groups can be affected by using high concentrated mineral acid or raised temperature due to the hydrolysis reaction (Barnes, 1999; Magistretti, 1980; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014) (Table 15.4 ).

Table 15.4.

Physical properties of common solvents used in phytochemistry (Barnes, 1999; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014).

| Solvent | Polarity index | Refractive index | B.P. | Specific gravity (20°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Pentane | 0.0 | 1.358 | 36 | |

| n-Hexane | 0.0 | 1.375 | 69 | 0.659 |

| Petroleum ether (low boiling) | 0.0 | – | 40–60 | |

| Petroleum ether (high boiling) | 0.0 | – | 60–80 | |

| Heptane | 0.0 | 1.387 | 98 | |

| Cyclohexane | 0.2 | 1.426 | 81 | 0.779 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 1.6 | 1.466 | 77 | 1.594 |

| Toluene | 2.4 | 1.496 | 111 | 0.867 |

| Xylene | 2.5 | 1.500 | 139 | 0.860 |

| Benzene | 2.7 | 1.501 | 80 | 0.879 |

| Diethyl ether | 2.8 | 1.353 | 35 | 0.714 |

| Dichloromethane (methylene chloride) | 3.1 | 1.424 | 41 | 1.325 |

| 1,2-Dichloroethane (ethylene chloride) | 3.5 | 1.445 | 84 | |

| Isopropanol (2-propanol) | 3.9 | 1.380 | 82 | 0.785 |

| n-Propanol | 4 | 1.380 | 97 | 0.804 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 4.0 | 1.407 | 65 | 0.887 |

| n-Butanol | 3.9 | 1.399 | 125 | 0.810 |

| Chloroform | 4.1 | 1.443 | 61 | 1.486 |

| Ethyl acetate | 4.4 | 1.370 | 77 | 0.901 |

| Acetone | 5.1 | 1.359 | 56 | 0.791 |

| Methanol | 5.1 | 1.329 | 65 | 0.792 |

| Ethanol | 5.2 | 1.361 | 78 | |

| Pyridine | 5.3 | 1.510 | 0.982 | |

| Acetonitrile | 5.8 | 1.344 | 82 | 0.782 |

| Acetic acid | 6.2 | 1.372 | 118 | 1.049 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | 7.2 | 1.477 | 189 | 1.101 |

| Water | 9.0 | 1.330 | 100 |

15.4.5. Types of extraction processes

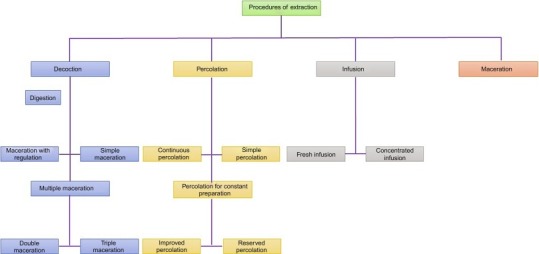

Classification of extraction can be based on heat. These are hot and cold extractions. Depending upon the physical state, extraction processes are categorized into the solid-liquid extraction and liquid extraction (Cos et al., 2006; Culture and Health, 1996; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014). Different methods of extraction techniques (Barnes, 1999) are summarized in Fig. 15.13 .

Fig. 15.13.

Different methods of extraction.

15.4.6. Cold and hot extraction

Cold extraction is performed at room temperature. Several types of cold extraction technique are available in small- as well as large-scale purposes like percolation, maceration, and superfluid extraction. Thermolabile components are mainly extracted by such types of techniques (Harborne, 1984).

The use of hot extraction depends on some key factors like prolonged time and higher temperature. Hot extraction processes include digestion, reflexion, and steam distillation. The major drawback of the hot extraction method is excess temperature and volatility of compounds. Due to these disadvantages, polymerization and decomposition of protein take place (Azwanida, 2015; Barnes, 1999).

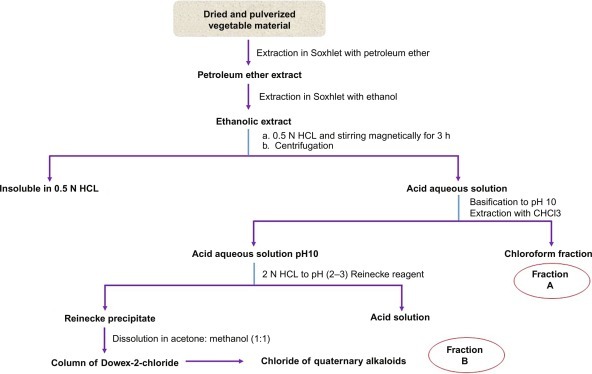

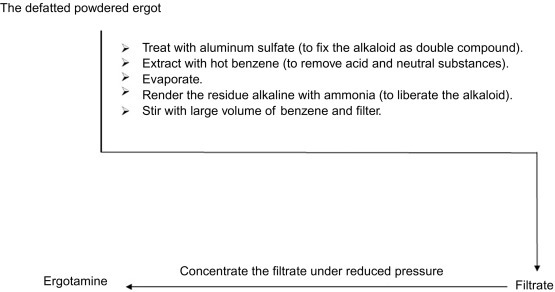

Fig. 15.14 describes the isolation techniques of indole alkaloids.

Fig. 15.14.

Extraction and purification techniques of indole alkaloids.

15.4.6.1. Liquid-liquid and solid-liquid extractions

If the precursor is liquid in nature, the partition method is applied, where the distribution coefficient between the liquid form and solvent is appreciable. This is an example of liquid-liquid extraction.

In the case of extraction from solids, there are several subtypes of solid-liquid extraction.

15.4.6.2. Maceration

In this method powder or bulk, plant compound is transferred in a stoppered container and covered with a solvent for a certain time until the solubilized part is dissolved in the solvent. It is an example of the cold extraction process (Cunha et al., 2004; Majors, 1996; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014; Phrompittayarat et al., 2007; Poole and Poole, 1996; Ronald, 1999; Sasidharan et al., 2008; Valérie, 2001; Woisky and Salantino, 1998).

15.4.6.3. Percolation

Indole-, isoquinoline-, and tropane-derived plant products are transferred in a percolation tube plugged with cotton with a filter. For maceration, the solvent is put in the plant material. The total experiment is carried on at room temperature. The extract along with extracted solvent is collected by a stopper at bellow. The process is continued until the proper evaporation for the last residue of the solvent from the percolator (Saberi, 2015).

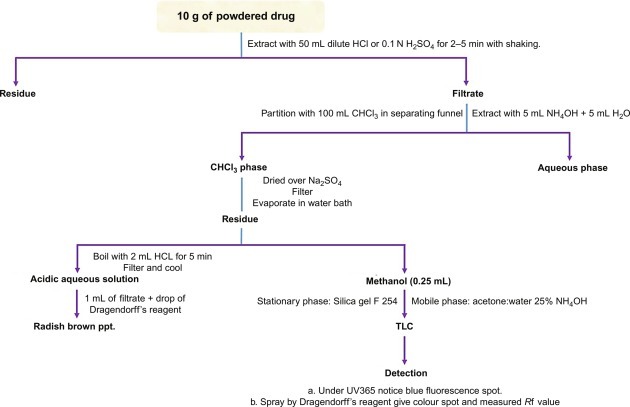

Fig. 15.15 describes the isolation techniques of datura alkaloids (tropane alkaloids).

Fig. 15.15.

Extraction and purification techniques of datura alkaloids.

15.4.6.4. Digestion

In this step, temperature about (40–60°C) is applied at the time of extraction. The process is suitable for thermostable plant materials. Modification of method is done by mixing the plants products using magnetic stirrer and mechanical stirrer. The extract is filtered after 8–12 h, and then the fresh solvent is added. The method is repeated until the extraction of desire solutes (Komárek et al., 2006; Pandey and Tripathi, 2014).

15.4.6.5. Infusion

In this step, the plant material is extracted by cold water or boiling water for a brief time (Pandey and Tripathi, 2014).

15.4.6.6. Decoction

This process is appropriate for extracting for thermostable and water-soluble plant materials. Firstly the plant material is boiled in water, cooled, and strained (Pandey and Tripathi, 2014).

15.4.6.7. Extraction with boiling solvents (Reflexion)

In this step, the plant material is kept with hot water. The solvent vapor is condensed by condenser fitted on top of the container and recycled (Johansen et al., 1996).

Tincture

Plant material extracted in presence of alcohol. Generally, ethyl alcohol is used at the ratio 1:5. Due to alcohol content, the tinctures are stored in the closed system to avoid decomposition.

15.4.7. Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE)

Another name of this extraction method is an accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) system or enhanced solvent extraction (ESE) system. In this technique, temperature and pressure gradually increase. This elevated temperature promotes the extraction process by increasing the diffusivity of the solvent, whereas increased pressure can promote the penetration process through matrix pore without altering the liquid state of organic solvent. The instrument provides better working efficiency under an inert atmosphere and with protection from light. The advantages of this extraction process are a requirement of less solvent and less time (Björn et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2013; Richter et al., 1996; Skalicka-Wozniak and Glowniak, 2012).

15.4.8. Soxhlet extraction

Soxhlet extraction is the best technique for the continuous extraction of a solid by a hot solvent.

Soxhlet apparatus is constructed by unique glass materials used for organic solvent extractions purpose. During the extraction procedure, the solvent is boiled gently inside round bottomed (RB) flask, the vapor passes through the side tube, is condensed by condenser, and falls drop by drop into thimble-containing material. By this away, Soxhlet is filled up gradually, and when it reaches at the top the tube it siphons over into the flask. The removal portion of the materials, which it has extracted and the process repeats (Huie, 2002a; Zygmunt and Namieśnik, 2003).

15.4.9. Steam distillation

The essential oil is isolated from natural product via a steam distillation process. This process is very simple where vapors are made by steam, passing through the compounds. The steam volatile oil is recovered by condensation, where oil detached from the water.

15.4.10. Hydrodistillation

Hydrodistillation process is a most popular technique for isolation of essential oil. Plant products are soaked in water and boiled using a heating mantle. The essential oil is separated out from the oil gland in the plant materials and transfer with the steam. Clevenger apparatus are used for condensing steam oil mixture and detaching the oil part from the aqueous portion (Farhat et al., 2009; Özek et al., 2010; Sahraoui et al., 2008).

15.4.11. Enfleurage

This process is mainly applied to a delicate fragrance. The flower petals are extended over a layer of refined fat, which picks up the odor of the flowers and the saturated fat is treated with a solvent. Mainly alcohol is used for soluble of the fragrant component. The residual fat is separated by cooling the alcoholic extract at 20°C. After separation of fatty substances, volatile component is collected from alcohol by rotary evaporator (Mahajan et al., 2015).

15.4.12. Supercritical fluid extraction

The manufacture of the supercritical fluid is performed by heating at an above critical temperature and compressing over the critical pressure. A supercritical fluid is a liquid as well as that of gas in nature. The penetration of supercritical fluid is like gas under pressure and can be handled as a liquid. CO2 is the most popular supercritical fluid. Another example like ethylene, ethane, propylene, propane, and nitrous oxide can also be used. CO2 has a comparatively low critical temperature (31.1°C) and pressure (73.8 bar). The extraction is performed at a temparature of 35°C and 36°C in the presence of CO2. The method has been in use in large scale. Sometimes methods are modified by the addition of polar compound for efficient extraction. Delicious flavor, perfume chemicals are manufactured by this sophisticated technique. The benefits of this technique are mild conditions, which is suitable for thermolabile compounds (Lutfun and Sarker, 2012; Patil and Shettigar, 2010; Zougagh et al., 2004).

15.4.13. Ultrasonic extraction

In this technique, high-frequency sound is applied to liberating the phytochemicals from the plant tissue. Ultrasound effect promotes the extraction used with mixtures of immiscible solvents. The major drawback of this technique is generating heat, which is harmful to thermolabile products. To avoid such types of problem, extraction is carried on under an ice bath to reduce the temperature. This process is not suitable for the isolation of large molecules like proteins or DNA (Vinatoru, 2001).

15.4.14. Microwave-assisted extraction

The electromagnetic radiations with a frequency range of 0.3–300 GHz are used in MAE. A microwave frequency of about 2.45 GHz is used as general domestic extraction purpose (Delazar et al., 2012). Microwave energy is passed through the solvent, with brief periods of cooling time as the process generates much heat. The electric field is responsible for the heating of substrates through the dipolar rotation and ionic conduction. Temperature is increased gradually with higher dielectric constant. In terms of yield value of an extract, microwaves extraction needs less time compared with Soxhlet extraction. Due to heat in microwaves technique, weak hydrogen bonds are broken down. So extraction of thermolabile compounds with low dielectric constant needs cold environment. To avoid this drawback, exhaust fans and solvent vapor detectors are not allowed in laboratory premises.

15.4.15. Solid-phase extraction