Abstract

Acute respiratory failure accounts for 25–40 % of ICU admissions and carries a mortality rate of 30 % or more. In this chapter, we classify acute respiratory failure in two main types, based on their primary physiologic abnormality:

Disorders of the airways, where increase of airway resistance to gas flow determines pharmacologic treatment and ventilatory strategies. These disorders are mainly asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Disorders of the alveoli, where a decrease of lung compliance mandates the use of higher ventilatory pressures that can recruit but also damage the lung. These disorders include the acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, and influenza.

Additional types of acute respiratory failure are described elsewhere in this book: disorders that result from neuromuscular disease in Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_19 and pulmonary disorders of the circulation, including pulmonary thromboembolism, in Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_27. Finally, we provide a section on weaning from mechanical ventilation, which includes the pathophysiology of the ventilatory load imposed by the prolonged acute respiratory failure, the possible ways to support the weakened respiratory system, and the current process of screening and testing for readiness to remove the ventilator.

Keywords: Acute respiratory failure, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Exacerbation of COPD, Status asthmaticus, Near-fatal asthma, Expiratory flow limitation, Lung-protective ventilation, Spontaneous breathing trial, Law of motion of the respiratory system

Introduction

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) defined as the acute onset of respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation accounts for 25–40 % of ICU admissions, depending on the demographics of each ICU and on the definition of ARF, which may include a specific degree of hypoxemia or a minimum duration of intubation [1–3]. Patients also develop ARF while in the ICU, so that as many as 50–60 % of ICU patients may be receiving mechanical ventilation at any time [2]. Patients with ARF have a longer ICU (median of 3–5 days) and hospital (median 15–18 days) stay and an increased mortality rate (30–50 %) than patients without ARF [1–3].

The burden of ARF continues after discharge from the acute care hospital. While pulmonary function per se may recover to the point of allowing life without dyspnea [4], survivors of severe ARF such as the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) endure physical disability that includes weakness, weight loss, a decline in activities of daily living, and inability to return to their former jobs [5, 6]. In addition, psychosocial dysfunction may include decreased intellectual function, loss of memory, impaired concentration [7], and a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) characterized by depression, anxiety, memory of pain, dyspnea, and nightmares [7, 8]. Finally, families of ARF patients share this psychological and material burden, as they worry about their family members’ survival as well as their own livelihood [9]. In this chapter we will classify ARF into two main categories, based on their effects on respiratory mechanics:

Diseases that affect primarily the airways, i.e., asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where the main physiological abnormality is an increase in airway resistance and consequent expiratory flow limitation

Diseases that affect primarily the alveoli, such as pneumonia and ARDS, where the main physiological abnormality is a decreased lung compliance resulting in the need for increased ventilatory pressures that may injure the lung

ARF from neuromuscular disease and pulmonary thromboembolism are discussed in Chaps. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_20 and 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_27, respectively.

This arrangement in two categories of increased airway resistance and decreased lung compliance follows the general law of motion of the respiratory system [10], where the pressure applied to the lung (P APPL) generates a flow of gas (V) that is opposed by the airways’ resistance (R AW) and that results in a change in lung volume (V T) that is facilitated by the respiratory compliance (C):

| 24.1 |

where P APPL equals the sum of the pressure generated by the respiratory muscles (P MUS), a negative pressure, and the pressure generated by the ventilator (P VENT), a positive pressure. Thinking in these terms greatly assists the understanding of the mechanical phenomena of respiratory disorders and their interaction with mechanical ventilation.

Acute Respiratory Failure of Airway Disease: Asthma and COPD

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by bronchial hyperreactivity and airflow obstruction. Asthma affects over 22 million adults in the USA, and it is the most common chronic disease of children [11]. Chronic inflammatory phenomena are responsible for the heightened production of mucous that contributes to increased resistance to airflow through the airways and may result in permanent structural damage (remodeling) associated with loss of lung function and reduced response to bronchodilator therapy [11].

Asthma exacerbations are generally caused by viral infections and are marked by dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and air hunger and objectively by a prolonged duration of expiration that is measured by a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and FEV1 over forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) [12, 13]. Patients who have had at least one such episode may be defined as “ exacerbation prone” and have an increased hazard to have further episodes and an accelerated loss of lung function [13]. These patients—about 20 % of all asthmatics—are responsible for the bulk of hospital admissions, mechanical ventilation, and tracheal intubation and for the majority of healthcare costs associated with asthma. Some of the risk factors that lead an asthma patient to be exacerbation prone include ongoing cigarette smoking, exposure to environmental allergens, poor compliance with maintenance therapy, chronic rhinosinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, and nonmedical factors such as poor social support, lack of private health insurance, and unemployment [12].

Acute treatment of severe exacerbations starts in the emergency department (ED). Most patients can be discharged home after stabilization; about 25 % are admitted to the hospital, and of these 5–10 % to the ICU [14]. Nebulized bronchodilators are the mainstay of the treatment of asthma exacerbation: nebulization of short-acting β-2 agonists (albuterol) and anticholinergics (ipratropium) is continued in the ICU, whether the patient is breathing unassisted, with noninvasive ventilation (NIV), or intubated. Corticosteroids are most commonly administered intravenously, e.g., methylprednisolone 60 mg every 6 h tapered over the following 2 to 3 weeks.

“ Status asthmaticus” (severe exacerbation that does not respond readily to the initial therapy) and “ near-fatal asthma” (status asthmaticus progressing to acute respiratory failure) describe the asthmatic patient who requires treatment in the ICU. Most of these patients will receive ventilatory assistance either by NIV or tracheal intubation. These patients have a mortality rate between 10 and 25 % [15].

Pathophysiology

Moderate hypoxemia develops in nearly all patients presenting to the ED with asthma exacerbation. Hypoxemia is related to a decrease in ventilation/perfusion secondary to airway plugging from increased, thickened tracheobronchial secretions. Hypoxemia can also result from hypoventilation, through a decrease in the alveolar PO2 caused by displacement of O2 from the alveolar air by the increased expired PCO2 [16].

Hypercarbia is also characteristic and typically time related: in the initial phase of the exacerbation, a fit patient is able to hyperventilate and compensate for the failure of CO2 elimination due to alveolar overdistention and decreased pulmonary blood flow (increased ventilation/perfusion and dead space). As the episode progresses untreated, fatigue may set in and hypoventilation with consequent hypercarbia will result.

From a mechanical standpoint, expiratory flow limitation is the key abnormality, which leads to lung hyperinflation and inability of exhaling the entire inspired volume. Once at steady state, this phenomenon (“breath stacking”) leads to a new and increased lung volume at end expiration (functional residual capacity [FRC]), which exerts a pressure higher than the normal “0” (atmospheric pressure) of end expiration. This new end-expiratory pressure is commonly referred to as “ auto-PEEP” or “intrinsic PEEP” (PEEPi) from its mechanical similarity to the PEEP set on a ventilator [17, 18]. Table 24.1 shows a summary of the effects of PEEP vs. PEEPi, highlighting similarities and differences. PEEPi remains a difficult concept to assimilate because it is not immediately “seen” on the ventilator screen. Figure 24.1 shows why that is the case and how to set the ventilator to detect PEEPi. Additional implications of PEEPi particularly regarding its effect on work of breathing that may hinder discontinuing ventilatory support are discussed in section “Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).”

Table 24.1.

Physiologic effects of externally applied positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) versus intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEPi) or “auto-PEEP”

| PEEP | PEEPi | |

|---|---|---|

| Alveolar recruitment, increased PaO2 | Yes | Yes |

| Alveolar overdistention, possible damage | Yes | Yes |

| Decreased venous return, hypotension | Yes | Yes |

| Increased work of breathing | No | Yes |

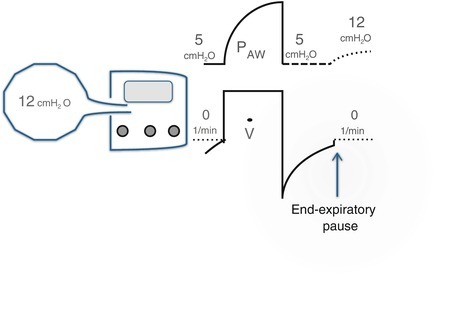

Fig. 24.1.

Method to detect intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEPi) from the airway pressure (P AW) trace on the ventilator screen. The alveolar pressure in the hyperinflated alveoli is 12 cmH2O. However, this pressure is not detected by the ventilator because the expiratory limb is open to atmospheric pressure or (like here) to the set PEEP. If we apply an end-expiratory pause (i.e., we occlude the expiratory limb), the alveoli-ventilator system will equilibrate at a pressure closer to the high alveolar pressure, which can be seen by the dashed line that follows the end-expiratory pause. In this explanatory case, the total PEEP is 12 cmH2O, that is, 7 cmH2O above the applied PEEP

Oxygen Supplementation and Mechanical Ventilation

Hypoxemia can occasionally be severe in an asthmatic attack. High O2 inspired fractions (FiO2) tend to increase PaCO2 by a few mmHg [19]. Limiting FiO2 to 40–60 % through a Venturi mask generally prevents a further rise of PaCO2 (Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_1). Occasionally, severe hypoxemia must be treated promptly with higher FiO2; one must be ready to provide ventilation by manual mask-bag ventilation, through a laryngeal mask airway, or by intubating the trachea.

Patients with signs of severe respiratory failure such as obtundation, shallow breathing, central cyanosis, and obvious fatigue must be promptly intubated to avoid progressing to respiratory arrest. Most patients with asthma exacerbation can be triaged to NIV in the form of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP). Either modality is effective because it provides positive pressure to the airways and facilitates exhalation [18]. The added ventilation provided by BiPAP may be of use in cases of diminished ventilatory drive and severe hypercapnea.

Less frequently, tracheal intubation and possibly prolonged invasive ventilation are necessary. The principal challenge of ventilating asthmatic patients is the presence of increased resistance to gas flow in the airways. On inspiration, this may limit the size of tidal volume; on expiration, it may cause hyperinflation and PEEPi. The combination of high inspiratory pressures and severe hyperinflation poses a risk for hemodynamic instability and barotrauma; limiting the size of V T may prevent these life-threatening complications. Permissive hypercapnea uses small V T limiting hyperinflation and allows PaCO2 to rise. With proper monitoring of arterial pH and hemodynamic variables, this strategy has been used safely in severe asthma [20]. A helium/oxygen gas mixture of 80:20 or 70:30 (“heliox”) decreases R AW in obstructed large airways because helium is less dense than nitrogen. Heliox is most indicated for upper airway obstruction where the airway is reduced to an orifice through which the low density of helium works best. It has been used with success in severe asthma [21], where the drawback is the inability to deliver high FiO2.

In cases that do not respond to standard treatment, inducing general anesthesia with inhaled anesthetic agents such as sevoflurane and isoflurane can provide additional bronchodilation. All inhaled anesthetic agents derived from halothane have bronchodilator properties independent of β-2 adrenergic and cholinergic receptors [21]. In the most severe cases of status asthmaticus, where essentially no V T reaches the alveoli, institution of cardiopulmonary bypass has been reported [22].

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD is a chronic disease characterized by progressive destruction of the elastic structure of the lung, chronic inflammation, and airflow limitation. Inflammatory and infectious phenomena predominate in some patients (chronic bronchitis type), expiratory flow limitation and lung hyperinflation in others (emphysema type). Most patients have elements of both. COPD affects approximately 24 million adults in the USA where it is the third leading cause of death [23]. Unlike other chronic illnesses such as cancer and heart disease, death from COPD is on a steep rise. It is clear that most of the impact of healthcare on COPD has to come from prevention and long-lasting treatment, but proper management of acute decompensations may slow the progression of the disease and avoid acute deaths.

Pathophysiology

The main physiological anomaly of COPD is alike to asthma, i.e., an increased airflow resistance with inspiratory and expiratory flow limitation. However, in asthma this is the result of chronic inflammation and airways’ hyperactivity and it can be controlled with proper management; in COPD there is chronic damage of the lung parenchyma by a toxin, generally tobacco, which progresses with time and is not fully reversible even when the cause is removed.

Chronic hypoxemia is frequent in COPD as the result of ongoing destruction of alveoli that decreases the sheer surface available for gas exchange. Hence, differently from the hypoxemia of alveolar diseases such as atelectasis or ARDS, hypoxemia of COPD is more readily responsive to supplemental O2 than to lung recruitment. Chronic O2 therapy ameliorates quality of life and survival rates of patients with severe COPD [24].

Chronic hypercarbia is more characteristic of COPD than of asthma, and it is secondary to wasted ventilation, i.e., physiological dead space caused by alveolar hyperinflation. Most commonly, hypercarbia is mild (less than 50 mmHg PaCO2) and the associated acidemia is compensated by retention of bicarbonate at the renal tubules. Patients with moderate-to-severe COPD may have serum bicarbonate levels of 28–32 mEq/L with nearly normal pH. Such finding on a chemistry profile may help in the evaluation of a stable COPD patient when an arterial blood gas analysis is not available, although caution must still be used to rule out a primary metabolic alkalosis. Late in the disease or during acute exacerbations, hypercarbia may worsen to level well above 50 mmHg PaCO2 from failure to sustain the burden of the increased work of breathing. Such a patient needs urgent support of ventilation to avoid CO2 narcosis and respiratory arrest.

From a mechanical standpoint, the hallmark of COPD is expiratory flow limitation. Like in asthma, there is a component of chronic airway inflammation and hyperreactivity. Unique to COPD is the progressive destruction of elastic tissue compromising the ability of the lungs to recoil passively to FRC. Hence, the end-expiratory lung volume increases, and the end-inspiratory lung volume has to increase accordingly to maintain V T. At steady state, the respiratory system resets the process of ventilation at a higher lung volume causing chronic lung hyperinflation (“barrel chest” on physical exam). Hyperinflation has unfavorable consequences on the mechanics of breathing, because (a) inspiration has to start from a flattened diaphragm and a less efficient shape for contraction and (b) more energy has to be spent to overcome the PEEPi generated by the larger end-expiratory volume with each breath (see previous section “Asthma”). The stable COPD patient with hyperinflation compensates for the added load by slightly decreasing the minute ventilation and retaining bicarbonate (above), but has to spend more energy to overcome these unfavorable mechanics. This can be a fragile steady state; when a perturbation occurs from infection, trauma, or surgery, the COPD patient is at risk for acute respiratory failure.

Acute Exacerbation of COPD

Acute exacerbations of COPD are characterized by dyspnea and increased sputum production/purulence related to recurrent bacterial infections of the tracheobronchial tree. Exacerbations are more frequent in a COPD patient with an FEV1 lower than 30 % of predicted (“GOLD” stage IV) [23]. These patients have approximately a 50 % chance to suffer two or more such episodes in 1 year [25]. Just like for asthma, exacerbations tend to diminish the functional status of the patient and increase the chance of a new episode. While only a minority of COPD patients with exacerbation is admitted to the ICU (generally associated with pneumonia), mortality is as high as 25 %. Most common factors associated with poor outcome include old age, comorbidity, and delay in the transfer to the ICU [26].

Pharmacologic therapy of patients with recurrent exacerbations (GOLD stages III–IV) outside the immediate emergency includes the combination of long-acting β-2 adrenergic (e.g., formoterol) and anticholinergic (e.g., tiotropium) bronchodilators with or without inhaled corticosteroids (budesonide). In the setting of acute exacerbations, nebulized short-acting β-2 adrenergic and anticholinergic bronchodilators (e.g., albuterol and ipratropium) provide superior flexibility of administration. Corticosteroids such as intravenous methylprednisolone 60–120 mg every 6 h for 3 days followed by a taper of oral prednisone starting at 60 mg/day are proven to be beneficial [27]. Antibioticsinclude azithromycin, third-generation cephalosporins, and quinolones with or without antipseudomonal activity depending upon the patient. O 2 supplementation is desired in the acute setting, with similar indications and cautions suggested for exacerbations of asthma (above). Mucolytics, expectorants, and chest physical therapy have little evidence of benefit [26]. Finally, surgical options exist for advanced COPD (GOLD stage IV). Volume reduction surgery can provide long-term symptomatic and outcome benefits for patients with upper-lobe emphysema, particularly when associated with physical therapy [28]. Lung transplantation is an option in selected patients (Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_55).

Mechanical Ventilation of COPD Patients

NIV is the standard of care for the uncomplicated exacerbation of COPD requiring ventilatory support [29]. Over the past 15 years, the use of NIV has increased significantly while the tracheal intubation and mortality rate in COPD exacerbation have decreased. Nevertheless, management of patients on NIV requires knowledge and vigilance: concern exists on a small but expanding number of patients that require tracheal intubation after failing NIV and who seem to have an increased mortality [30]. These patients might have benefited from tracheal intubation upon admission or at the earliest sign of failed NIV. Tracheal intubation should be considered in patients with a decreased sensorium, hyperactive delirium, acute comorbidities such as congestive heart failure and pneumonia, hemodynamic instability, and early failure to improve with NIV [30].

When delivering mechanical ventilation, whether by NIV or endotracheal intubation, the main physiologic challenge with COPD is the increased R AW. On inspiration, high R AW requires a higher driving pressure for a given V T, leading to increased work of breathing and possibly hypoventilation; on expiration, high R AW causes dynamic hyperinflation and PEEPi, with consequent increased work of breathing and possibly hypotension. Reviewing the interactions between pressure, gas flow, lung volume, and patient’s R AW and C as described in Eq. (24.1) helps one to understand ventilation in COPD and allows measurement of physiological variables at the bedside (Fig. 24.2).

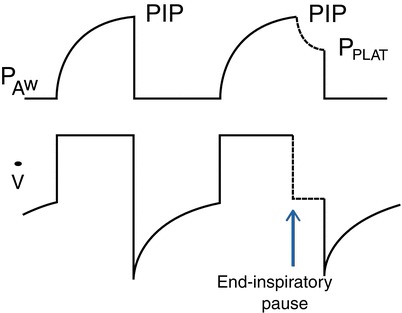

Fig. 24.2.

End-inspiratory pause to separate the peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) from the plateau pressure (P PLAT). The ventilator is set in the volume control, square-wave flow pattern at a set flow rate. The end-inspiratory pause (arrow) interrupts the flow and separates PIP (determined by tidal volume, airway resistance, and respiratory compliance) from P PLAT (determined by tidal volume and respiratory compliance). Measurements of PIP and P PLAT allow to calculate airways’ resistance and respiratory compliance, as illustrated in Eqs. (24.3) and (24.5) in the text

Inspiratory phenomena: hypoventilation (from Eq. (24.1)):

| 24.2 |

where ∆P is the difference between the dynamic pressure at end inspiration or “peak inspiratory pressure” (PIP) and the static pressure at end inspiration or “plateau pressure” (P PLAT). By applying a short pause (inspiratory hold) at end inspiration, the inspiratory flow ceases, and the pressure will settle at a lower level that is no longer affected by or R AW, the P PLAT. We can rewrite Eq. (24.2) with terms that we can obtain at the bedside:

| 24.3 |

For example, with a set V T of 600 mL and inspiratory flow of 60 L/min (=1 L/s) generating a PIP of 10 cmH2O and P PLAT of 8 cmH2O, we have a R AW of 2 cmH2O/l/s, which is normal.

It is important to note that the PIP is not the primary pressure that reaches the alveoli; such pressure is the P PLAT, which is a surrogate of alveolar pressure. Hence, the pressure that recruits alveoli or damages alveoli is not the PIP but the P PLAT. On volume ventilation with a descending flow ramp and on pressure ventilation (Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_26), the flow rate at end expiration is lower than in early inspiration and can be equal to 0. In such cases, the end-inspiratory pressure is a P PLAT, and there is no need of an inspiratory hold.

Expiratory phenomena: increased work of breathing. The main expiratory phenomenon in COPD is flow limitation and generation of PEEPi (section “Asthma”). Figure 24.1 shows how PEEPi can be measured at the bedside by occluding the expiratory limb of the ventilator, i.e., performing an end-expiratory hold maneuver. This provides a closed ventilator/patient system that equilibrates at a pressure close to the one in the hyperinflated alveoli, as long as the airways to those alveoli are not occluded. However, the expiratory hold maneuver is reliable only if the system is allowed some time (1–3 s.) to equilibrate, which requires a slow respiratory rate with no inspiratory effort during the maneuver. This unfortunately is not a common occurrence in the ICU, as opposed, e.g., under anesthesia, where patients are commonly paralyzed. In the spontaneously breathing patient, PEEPi can be measured with the aid of an esophageal balloon to measure pleural pressure [31]. Short of that, which is not routine practice, one can just detect the expiratory flow limitation by the inspection of the flow trace on the ventilator display. Normally, expiratory flow reaches a baseline of 0 flow before the start of the next breath; with flow limitation, the trace will be abruptly truncated at the start of the next breath without any visible baseline of 0 flow (Fig. 24.1).

PEEPi may decrease V T and induce hypoventilation with the pressure-limited modes [18]. On pressure control, V T is generated by the “driving pressure,” which is the set inspiratory pressure above PEEP. If PEEPi is present, the actual end-expiratory pressure will be the sum of PEEP and PEEPi. Hence, the set inspiratory pressure will be delivered from the total PEEP rather than the set PEEP, thus decreasing the actual driving pressure and V T.

PEEPi increases the work of breathing. Any amount of PEEPi needs to be overcome by the respiratory muscle pump before inspiration can begin. Hence, the work of the respiratory muscles against PEEPi is wasted work because it does not generate any V T. From a practical standpoint, it is important to realize that patients with COPD may conduct their activities of daily living with an increased work of breathing due to PEEPi. Hence, they may be very sensitive to even minor increases in the load of breathing associated with a flare of COPD and develop ARF. In mechanically ventilated patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation, PEEPi may be a daunting barrier to discontinuing mechanical ventilation (section “Weaning from Mechanical Ventilation”).

Acute Respiratory Failure of Alveolar Injury: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Pneumonia, Cardiogenic Edema, and Influenza

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

ARDS is a syndrome of acute respiratory failure characterized by permeability pulmonary edema, diffuse alveolar infiltrates, and hypoxemia often requiring tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. The most recent definition of ARDS includes three mutually exclusive levels of hypoxemia that identify mild, moderate, and severe ARDS [32]. Distinguishing “severe ARDS” is important in the light of recent evidence that some treatment for ARDS that has not proven a tangible benefit in the overall population has improved outcomes in the specific subgroup of patients with severe hypoxemia (see later in this section). ARDS is an inflammatory syndrome that can arise within the lung from acute injuries such as pneumonia, aspiration pneumonitis, and lung contusion, or from outside the lung, as a consequence of systemic sepsis, transfusions, burns, acute pancreatitis, etc. [33]. The incidence of ARDS in the US has been estimated around 75 cases every 100,000 individuals or 190,000 per year, with a mortality rate between 30 and 60 %, yielding about 100,000 deaths and about the same number of survivors each year [34]. Survivors of ARDS have received heightened interest in the past decade, which has provided new and robust information on their long-term outcome (section “Introduction”) [6].

Pathophysiology

The acute alveolar damage of ARDS is an intense inflammatory injury of the alveolar epithelium and endothelium provoked by cellular and soluble mediators from the causatory event [33]. Such injury damages the lung parenchyma with edema and disruption of the alveolar walls, extravasation of blood cells and plasma into the alveolar spaces, and thickening of the epithelial layer with deposits reminiscent of the hyaline membranes of the premature neonate. This initial phase is characterized by inhomogeneity of alveolar lesions with areas of edema, consolidation, or collapse next to areas seemingly normally aerated and others overdistended. This inhomogeneity, which became apparent with the introduction of lung computed tomography (CT) scanning [35], is such that a pressure applied at the airway may affect areas that get recruited, areas that cannot be recruited, and areas that do not need to be recruited at all. Thus, mechanical ventilation can recruit some alveoli and damage others within the same breath. The balance of these two effects will determine the progression towards healing vs. exacerbating the existing injury (“ventilator-induced lung injury” [VILI]) [36]. In a later phase, the lung parenchyma is progressively occupied by inflammatory infiltrates, and edema is substituted by collagen deposition and remodeling (fibroproliferative phase) [33]. This phase, often overlapping within the same lung with the acute changes described above, results in the need for further increase in ventilatory pressures, possibly perpetuating the lung injury.

From a gas exchange standpoint, both hypoxemia and hypercarbia occur. Hypoxemia is secondary to venous admixture (shunting and low ventilation/perfusion ratio) and responds erratically to increasing the FiO2. Recruitment of collapsed alveoli forms the core of treating hypoxemia in ARDS; optimal recruitment not only increases PaO2, but optimizes lung mechanics and may limit VILI [36]. Hypercarbia is due to decreased pulmonary blood flow from vasoconstriction (hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, inflammatory mediators), vascular occlusion, and remodeling [37] and results in dead space ventilation. High dead space ventilation may require high minute ventilation and may perpetuate VILI.

From a mechanical standpoint, ARDS is a syndrome of low compliance. From the law of motion of the respiratory system Eq. (24.1):

| 24.4 |

where ∆V is the difference in lung volume between end inspiration and end expiration, i.e., the V T; P is the end-inspiratory pressure at 0 inspiratory flow, i.e., the P PLAT. Hence:

| 24.5 |

For example, on volume control ventilation of 400 mL generating a PIP of 12 cmH2O and P PLAT of 10 cmH2O, we have a C of 40 mL/cmH2O, which is approximately half of the normal C. These parameters can be measured with relative ease and allow calculation of R AW and C at the bedside (see Eqs. (24.1), (24.2), and (24.3) and Fig. 24.2), but a few caveats need to be well thought out:

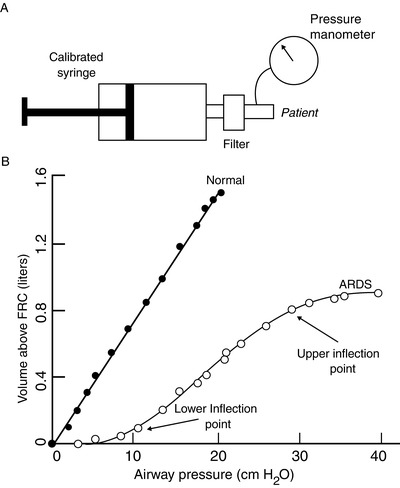

Using the V T as the ∆V assumes that C does not change at different lung volumes. While this is mostly correct in the normal individual, it may not be in ARDS. Figure 24.3 shows the relationship between P PLAT and V T (the slope of which is C) in normal and in ARDS. This relationship is almost linear in the normal state, i.e., C does not change with lung volume. On the contrary, in ARDS the slope is lower and the relationship sigmoid. This implies that with ARDS, the value of C may change with different inspiratory pressures, expiratory pressures, and V T’s.

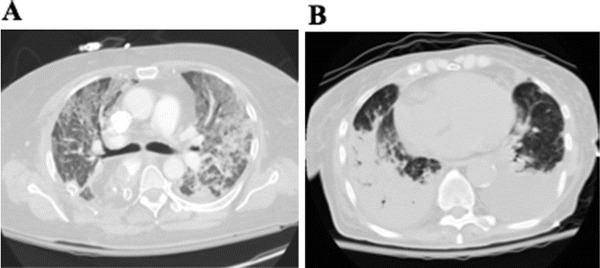

We are measuring the overall C of an inhomogeneous lung, meaning that the patterns of distributions of lung lesions in ARDS may differ significantly while the same compliance is obtained. The two patients in Fig. 24.4 had similarly low compliance values measured (correctly) at the bedside. One can easily see how the set V T will distribute fairly evenly in patient A even though at high inspiratory pressures; in patient B, the same V T will reach almost exclusively the ventral areas of the lungs, likely overdistending them and producing negligible recruitment of the dorsal areas.

We are measuring respiratory C as pertaining to the whole respiratory system (C RS), which is made up by the compliance of two structures in series, the lung and the chest wall:

| 24.6 |

where C L indicates C of the lung and C CW indicates C of the chest wall. We are interested in C L, because the chest wall does not need recruitment and does not get injured. However, a “tight” chest wall is still important because it will increase ventilating pressures without increasing pressures within the lung. Hence, a decreased C CW may limit lung recruitment and prevent lung injury at the same time. What determines alveolar recruitment and damage is the pressure across the lung or “transpulmonary pressure” (P TP), which is the difference between the two pressures surrounding the lung, i.e., the alveolar pressure (P ALV) and the pleural (P PL) pressure:

| 24.7 |

Unfortunately, neither P ALV nor P PL can be directly measured, but they are reasonably estimated by P PLAT and esophageal pressure (P ESO), respectively [38]. Hence:

| 24.8 |

P ESO has been used in clinical research as a target to overcome lung collapse at end expiration with PEEP. This method resulted in higher applied PEEP, enhanced recruitment, and increased PaO2 [39]. Measuring P ESO is not routine in the ICU because it requires specialized equipment and trained personnel. However, by understanding this concept, one can adjust ventilating pressures (P PLAT and PEEP) to somewhat higher values in patients with a low C CW, knowing that a lower P TP is being “seen” by the lung than would be with a normal C CW.

Fig. 24.3.

Semi-static pressure/volume (P/V) relationship (i.e., compliance) of the respiratory system in normal and ARDS individuals (b), obtained with serial insufflation of equal volumes of gas a few seconds apart (semi-static) through a calibrated super syringe (a). The normal P/V relationship is nearly linear, with a compliance of approximately 80 mL/cmH2O. The ARDS relationship is moved to the right (lower compliance) and is sigmoid, indicating that compliance varies with lung volume. Lower and upper “inflection points” indicate segments of the curve at which the compliance changes; these two points suggest values of airway pressure to set the PEEP (lower) and the inspiratory plateau pressure (higher). The segment of the curve between these set PEEP and plateau pressure should have the most favorable compliance to ventilate the patient at (Reproduced with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health: Crimi E, Hess DR: Respiratory Monitoring. In: Bigatello LM Senior Ed.: Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Fifth Edition. Wolters Kluwer Health, 2009.) [93]

Fig. 24.4.

Computed tomography scans of two patients with ARDS, both with a low value of respiratory compliance measured at the bedside: ~30 mL/cmH2O. In patient A, a set inspiratory pressure will distribute fairly uniformly, moving a small tidal volume and likely recruiting some lung over the tidal insufflation. In patient B, the same pressure will deliver a similar tidal volume (same compliance), but recruitment may be minimal, because the majority of lung tissue, particularly the massive consolidation in the right lung, may not inflate at all, while the seemingly healthy lung that will receive the pressure may have no alveolar unit to recruit and may become overdistended during the tidal insufflation

Lung-Protective Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation may injure the lung. Experimental evidence of lung injury by high ventilatory pressure/volume or by insufficient PEEP has been available for decades [40], but clinicians would see little alternative to using high ventilatory settings when ARDS patients were often profoundly hypoxemic or hypercarbic. In such cases, higher ventilatory pressures might have been the only way to avoid death (at least temporarily). With the advent of modern techniques of ventilation and improved critical care practice in general, the time was ripe for change. This happened with the demonstration that a V T of 6 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW) decreased the absolute mortality rate of patients with ARDS by about 10 % [41]. The use of 6–8 mL/kg IBW V T has become standard of care of ventilating the ARDS lung, and a broader strategy of “lung-protective ventilation” has been developed [1, 36]. The following are considerations that are still debated as evidence-based guidelines of lung-protective ventilation continue to be developed:

Using a V T of 6 mL/kg IBW applies to patients with ARDS, not necessarily to all patients that are intubated and ventilated. In non-ARDS patients, such as immediate postoperative patients, or patients who are in the process of weaning from ventilatory support, such low VT may sometimes result in insufficient ventilatory support and promote atelectasis.

Having demonstrated the beneficial effect of a 6 vs. 12 mL/kg IBW V T does not forbid that in some patients 7 or 5 mL/kg would be best. In a heterogeneously injured lung (section “Pathophysiology”), the inspiratory pressure generated by a 6 ml/kg V T may or may not recruit collapsed alveoli and/or may damage inflated alveoli [42, 43]. Using a higher V T or applying other ways to increase alveolar pressure such as higher PEEP or a recruitment maneuver [44] may injure the lung. Using V T lower than 6 mL/kg may limit alveolar damage but may derecruit the lung and decrease V T to the point of needing the assist of additional means to rescue gas exchange [43] (section “Extracorporeal Circulation”).

Setting the best level of PEEP needs further definition. PEEP helps to maintain alveoli open throughout the respiratory cycle (as it occurs without PEEP under normal circumstances) and prevents expiratory VILI [40]. A number of ways have been suggested to identify the ideal level of PEEP to maximize recruitment and avoid overdistention. Constructing a semi-static P/V curve by insufflating the lung with increasing volumes (Fig. 24.3) may accomplish this task, but it is cumbersome and imprecise [45]. Functional CT scan images allow discriminating between various degrees of alveolar inflation [43] but are currently limited to specialized centers. Alternatively, a bedside “PEEP trial” can prove useful. With the patient on volume ventilation exerting no or minimal spontaneous effort, PEEP is increased by, e.g., 2 cmH2O; for a set V T , the P PLAT is measured before and after the intervention; a decrease or no significant change of P PLAT indicates that recruitment has occurred; an increase of about the same as the increase of PEEP is insignificant, and an increase of more than 2 cmH2O indicates overdistention. The PaO2 will likely increase or stay the same until severe overdistention occurs. The trial can continue by small increments of PEEP until signs of overdistention or untoward hemodynamic effects are detected; the trial should be repeated at least daily in early ARDS because the mechanics of the lung with acute injury change rapidly.

Setting the best FiO 2. Limiting FiO2 prevents O2 toxicity and absorption atelectasis. O2 toxicity is related to both FiO2 and duration of exposure, but specifics on neither are available. Practically, it is sensible to limit FiO2 to reach O2 saturation above 90 % unless other factors limiting O2 delivery are present, such as profound anemia or low cardiac output. The current focus on lung-protective ventilation tends to prioritize optimizing respiratory mechanics over avoiding O2 toxicity. Most would agree that an FiO2 of 60 % or less is desirable and that an FiO2 of 40 % or less is safe.

Prone Ventilation

Ventilating ARDS patients in the prone position consistently improves PaO2 and, to a lesser extent, PaCO2. This effect lasts throughout the prone period and regresses over different time periods in the supine position [46]. The mechanisms are related to the gravity-induced distribution of lung lesions over a ventral-to-dorsal gradient (section “Pathophysiology”). When the patient is turned from supine to prone, the gravitational gradient is reduced but not reversed, resulting in a more homogeneous distribution of ventilation (Fig. 24.5). This new architecture is more apt to the recruiting effect of positive pressure, whether PEEP or recruitment maneuvers, improving gas exchange and respiratory mechanics [47]. When applied for prolonged periods of time in patients with the most severe level of hypoxemia, prone ventilation improves gas exchange, time on ventilator, and survival [48].

Fig. 24.5.

Computed tomography scans of the lungs of a patient with ARDS. Left panel is during supine ventilation, right panel prone. Note the anatomical distribution of the lung consolidations along a gravitational gradient in the supine position, which is nearly reversed in the prone position (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. © 2014 American Thoracic Society. Gattinoni L, Taccone P, Carlesso E, Marini JJ. 2013. Prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Rationale, Indications, and limits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 188:1286–1293; Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.) [46]

Biphasic Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP), Pressure Control Inverse Ratio Ventilation (PCIRV), and Airway Pressure Release Ventilation (APRV) [49]

All these modes are forms of pressure control ventilation where two levels of P AW are set, and spontaneous breathing occurs at both levels. In the absence of spontaneous breathing, these modes are pressure controlled with various inspiratory times. With BiPAP, commonly used with NIV, spontaneous breathing at the low P AW may be supported by a set inspiratory pressure. With PCIRV, a longer inspiratory time promotes recruitment through an increase in mean airway pressure:

| 24.9 |

where T I is the set inspiratory time, T E the expiratory time, and T TOT the total cycle time. With APRV, V T occurs by releasing the high P AW for a short period of time to allow exhalation. Through spontaneous breathing, these ventilatory modalities may promote alveolar recruitment; in experienced hands, they can successfully optimize gas exchange in patients with severe ARF. However, at this time there is no evidence suggesting an additional effect on clinical outcomes.

High-frequency oscillation (HFO) delivers very small V T’s at very high rates (3–15 per second or 3–5 Hz). Oxygenation occurs through the constantly inflated alveoli, and CO2 is moved along through the airways by the small V T’s [50]. Ideally, this system provides gas exchange without the trauma of expiratory alveolar closure. However, HFO has failed to show any benefit other than increased PaO2 in early and established ARDS when compared with a lung-protective strategy [51, 52].

Pharmacologic Treatment of ARDS

Corticosteroids

The use of corticosteroids for ARDS has robust biological rationale in their potent anti-inflammatory effects that could benefit particularly the late “fibroproliferative” phase of ARDS. Anecdotal experience as well as early reports of improved gas exchange, respiratory mechanics, and higher survival rates [53] encouraged the widespread use of pharmacologic-dose protocols of corticosteroids in patients with non-resolving ARDS. However, a more recent and methodologically superior study failed to confirm a tangible benefit beyond the better physiologic parameters [54]. Steroid therapy may provide both beneficial anti-inflammatory effects and dangerous side effects such as immunosuppression, myopathy, and hyperglycemia; at this time, a favorable balance of these contrasting effects has not been found, and their use in ARDS is not recommended.

Inhaled Nitric Oxide (NO)

Inhaled nitric oxide (NO) is a selective pulmonary vasodilator that reduces pulmonary artery pressure and increases PaO2 in patients with ARDS [55, 56]. However, its effect is limited in time and has not resulted in any significant improvement in outcome in a number of controlled clinical trials [57]. The effect of inhaled NO can be enhanced by a number of associated treatments, such as selective intravenous vasoconstrictors, surfactant, prone ventilation, and HFO; however, none has affected outcome. Its role in ARDS is currently limited to situations of severe hypoxemia as a temporary means to increase PaO2 while the appropriate ventilatory strategy sets in.

Muscle Relaxants

Pharmacologically induced muscle relaxation can be employed as a measure to completely control mechanical ventilation to treat severe hypoxemia refractory to deep sedation alone. The theorized benefits of muscle relaxants in ARDS include improved patient-ventilator synchrony, diminished oxygen consumption, and a blunted inflammatory response via diminished interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 expression. The well-recognized adverse effects of neuromuscular blockade, including loss of neurologic evaluation and potential prolonged weakness, have limited the use of these drugs (Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_12). However, recent data provide evidence of improved outcomes when muscle paralysis is used for short periods of time in the initial management of severe ARDS with refractory hypoxemia [58]. Patients that are chemically paralyzed must be appropriately sedated with a hypnotic or amnestic agent to assure unawareness. Preferred agents are those with minimal hemodynamic effects and predictable duration of action even in the presence of organ dysfunction, such as cisatracurium.

Other Pharmacologic Interventions

Other pharmacologic interventions have been studied and clinically tested over the years. These include surfactant replacement; anti-inflammatory agents other than corticosteroids, such as ketoconazole, pentoxifylline, N-acetylcysteine, and statins; anticoagulants such as recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), anti-thrombin III, activated protein C, and heparin; and agents that enhance edema fluid clearance such as β-2 adrenergic agonists. A few of these interventions have been studied with large multicenter controlled trials and none have shown any benefit. We refer to recent reviews for discussion and references [33, 59].

Conservative fluid management may prevent pulmonary edema and improve gas exchange and respiratory mechanics, particularly in the early phase of ARDS where alveolar edema is most pronounced [33]. Recommendations of a fluid-conservative management have been supported by physiologic data, including those for the use of diuretics with or without associated colloids [60]. Based on a recent study of 1000 ARDS patients not in shock that show a decrease in ventilator days and ICU stay, it seems reasonable to implement a conservative fluid management strategy in hemodynamically stable ARDS patients [61].

Extracorporeal Circulation

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCOR) have been part of the treatment of ARDS since shortly after its description in 1967. The first randomized trial of ECMO for ARDS, also the first large trial of any intervention for ARDS [62], failed to show any benefit in a cohort of extremely ill patients who carried an overall mortality rate of 90 %. However, the concept of protecting the lung from mechanical ventilation remained valid and was revived in the last decade owing to the renewed emphasis on VILI as well as the availability of extracorporeal technology that minimizes hemorrhagic complications and avoids traumatic vascular cannulation [63]. A clinical trial using newer ECMO techniques [64] has provided evidence of significant clinical benefit. Widespread reporting of increased use of ECMO in recent pandemics of influenza [65] has contributed to the renewed enthusiasm for extracorporeal means of support in patients with severe forms of ARF. A worldwide ECMO registry and comprehensive guidelines are published by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) at http://www.elsonet.org.

Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema (See Also Chaps. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_51 and 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_55)

The clinical presentation of acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema can be similar to ARDS in ICU patients with complex physiology, in whom the classic picture of acute left ventricular (LV) failure with dyspnea and hypotension and acute coronary syndrome is unlikely to be seen. The fundamental difference between ARDS and acute cardiogenic edema is that the former is caused by an injury of the alveolar epithelium and endothelium, and the latter carries minimal anatomical injury. If the cause of acute myocardial dysfunction is treated, the respiratory symptoms resolve rapidly. The differential diagnosis of cardiogenic edema is based on physical examination, chest radiogram, electrocardiogram, transthoracic echocardiography, and sometimes invasive hemodynamic monitoring. Useful biomarkers are plasma levels of natriuretic peptides (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP] and the N-terminal proBNP), which are cleaved from a prohormone released from myocytes in response to ventricular dilatation and pressure overload. Pharmacologic treatment of acute cardiogenic edema is based on diuretics and vasodilators, specifically ACE inhibitors and nitrates [66].

Mechanical ventilation is indicated in the presence of respiratory distress and hypoxemia. NIV with BiPAP or CPAP is the standard of care for acute, noncomplicated cardiogenic edema. Both modalities seem equivalent and they are superior to standard medical care in reducing the need for intubation and decreasing mortality [67]. CPAP and BiPAP recruit alveolar units and may counterbalance hydrostatic forces that lead to edema formation [68]. A decreased venous return and lower ejection of the right ventricle (RV) lessen the diastolic filling of the left ventricle (LV); the increased external pressure on the LV wall decreases afterload and favors ejection.

Pneumonia (See Also Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_32)

Pneumonia may both cause and complicate ARF. Pneumonia in the ICU includes community-acquired (CAP) and healthcare-acquired (HAP) pneumonia. Both entities, although dissimilar in their microbiologic flora, carry a high in-hospital mortality rate, use of healthcare resources, and further excess mortality over the subsequent year [69, 70]. Mechanical ventilation of ARF from pneumonia shares many of the features of other causes of alveolar damage discussed throughout this section.

Influenza

Influenza constitutes one of the most common causes of admissions to medical ICUs in the winter months and beyond. A number of recent pandemics of influenza have generated numerous reports that helped characterize the salient epidemiologic and clinical features of ARF associated with influenza. The presentation is nonspecific, with the acute onset of cough and fever being the most consistent symptoms. A variable percentage of patients (depending upon the different viruses and the preexisting conditions) develop ARF and necessitate admission to the ICU and intubation and mechanical ventilation. The mortality has varied throughout the 10-year spectrum of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) to avian influenza H7N9 [65, 71, 72]. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and confirmed with viral isolation techniques. A chest radiograph is nearly always obtained and frequently shows a pattern of bilateral infiltrates consistent with ARDS. The therapy, in addition to antiviral drugs, consists of respiratory support with mechanical ventilation using the principles outlined above for ARDS. Of particular interest has been the use of extracorporeal methods of support as outlined in section “Extracorporeal Circulation.”

Weaning from Mechanical Ventilation

ICU patients with ARF may follow one of the three main trajectories of recovery: (a) those who get better rapidly (e.g., exacerbation of COPD on BiPAP, uncomplicated thoracoabdominal surgery) and are extubated for 24–48 h, (b) those with a longer ICU course (e.g., pneumonia and septic shock, complex thoracic trauma, bowel perforation, and resection in an elderly person) who recover without protracted organ failure in a week to 10-day time, and (c) those who have an unstable course with multiple organ failures and require prolonged ventilatory support often through a tracheostomy [73, 74]. The first group is the largest and has a very good prognosis; the third group is only 10–15 % of ARF patients but has a long hospital course, has a high mortality, and accounts for the majority of the costs [75, 76].

Through the remainder of this section, we will focus on those patients with longer courses of ARF (second and third groups above), and we will review (a) the basic physiology behind the need for ventilatory support, (b) the interventions available to maximize the probability of success, and (c) the assessment of readiness to discontinue ventilatory support.

Pathophysiology of Prolonged Respiratory Failure: An Imbalance Between Muscle Pump and Mechanical Load Imposed by the Illness

Equation (24.1) enables to understand the interactions between patient and ventilator in the presence of abnormal respiratory system mechanics just like described above for the acute phase of ARF. The pump is P MUS, and the load is the R AW (resistive load) and 1/C (elastic load). Dysfunction of the muscle pump is almost universal in patients who have been mechanically ventilated for several days, but its intensity is variable and its ultimate effect on the duration of weaning unsettled (see also Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_19). A number of factors contribute to respiratory muscle dysfunction:

Catabolism, underfeeding, and deconditioning. The neurohumoral response to critical illness results primarily in loss of muscle proteins that may persist well beyond the acute unstable phase [77]. Appropriate nutritional support is key to recovery, but the timing, amount, and composition of it are still largely debated [78]. It has been observed that patients undergoing enteral nutrition are often underfed during weaning because of interruptions; care must be taken to minimize such interruptions and/or feed at increased rates to compensate [79]. Deconditioning is essentially inevitable, but its extent may be limited by early interventions that emphasize assisted ventilation, control of excessive sedation and of delirium (Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_20), in-bed occupational and physical therapy, and early mobilization [80, 81].

ICU-acquired paresis or its numerous other denominations occur in as many as 30 % of patients after days of sedation and mechanical ventilation [82]. This entity and its clinical implications are presented in Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_19. Although no study of weaning mechanical ventilation has specifically targeted weak patients, ICU-acquired paresis is predictably associated with longer weaning times [83].

Prevention of muscle atrophy . Respiratory muscle atrophy may occur when some or all the above factors occur in association with controlled mechanical ventilation [84]. Even short times of full ventilation with no spontaneous breathing activity trigger histological changes in respiratory muscle fibers compatible with muscle dysfunction and early atrophy [84]. Preventive actions against generalized weakness and muscle atrophy include recognition and treatment of infections, limited use of corticosteroids and muscular relaxants (particularly curare based), close control of blood glucose, and early mobilization. Respiratory muscle atrophy can be prevented or lessened by allowing spontaneous breathing (partial ventilation) from the earliest possible time of ARF.

Increased Ventilatory Load

The mechanical load to ventilation can be resistive, e.g., COPD, or elastic, e.g., ARDS. The extent of an increased R AW or a decreased C RS can be assessed at the bedside in spontaneously breathing patients as described in Fig. 24.2 and related text. We recommend this practice as part of daily evaluation of stable patients undergoing a program of discontinuation of mechanical ventilation. The main barrier to obtain reliable measurements of mechanics in this patient population is the presence of spontaneous breathing; however, in many cases, with appropriate coaching and at times a short-acting sedative, it will be possible to achieve the necessary inspiratory and expiratory hold maneuvers.

A resistive load is common in asthma and COPD, but it may also occur in any patient with ARF during acute attacks of bronchospasm due to allergy, airway infections, or mechanical irritation from, e.g., an intraluminal mass, trauma, or instrumentation [18, 85]. Within the context of resistive load, an important phenomenon is the patient’s failure to trigger an assisted breath because of inability to overcome PEEPi. Figure 24.6 shows this phenomenon. It is important to note that the ventilator will not count the non-triggered breaths even though it displays them, thus underestimating the true respiratory rate, leading the unaware clinician to a false sense of reassurance of a “normal” respiratory rate that may be substantially lower than the patient’s.

An elastic load is common in patients recovering from ARDS, pneumonia, or severe lung contusion. A frequent cause of elastic load is pulmonary edema due to residual lung injury, hypoproteinemia, and volume overload, particularly in the presence of LV dysfunction or renal insufficiency. Induced diuresis is a common prescription in a ventilatory unit, and management of volume status, fluid, and electrolytes balances a related challenge. Elastic load can be offset by an increase in mean P AW [see Eq. (24.9)] and consequent recruitment. An attractive way to increase mean P AW is by the applications of periodic recruitment maneuvers with CPAP, BiPAP, or sighs [86]. Elastic load can also come from pathology of the chest wall, such as large pleural effusions, abdominal distention, and thoracic deformities due to trauma or surgery. Pleural effusions may contribute to increase elastic work of breathing and worsen gas exchange during weaning from mechanical ventilation. However, these effects may be often overestimated, because the effect of their drainage can be remarkably unrewarding [87].

Fig. 24.6.

Inspiratory flow, airway pressure, and esophageal pressure traces showing the mechanism of ineffective triggering in the presence of intrinsic PEEP (PEEPi). In the first breath, PEEPi is measured as the delay between the start of the breathing effort (negative dip of the esophageal pressure, a surrogate of pleural pressure) and the point at which the flow trace becomes positive—in this case approximately 5 cmH2O. In the second breath, the effort, roughly represented by the esophageal pressure downslope, is equal, but no breath is started. This represents a “missed breath” where the negative pleural pressure generated by the patient is not sufficient to trigger the ventilator, indicating the PEEPi must have been higher than in the previous breath (With kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Intensive Care Medicine, Reduction of patient-ventilator asynchrony by reducing tidal volume during pressure support ventilation, 34, 2008, 1477–1486, Thille AW, Cabello B, Galia F, Lyazidi A, Brochard L.) [85]

Preparing the Patient to Discontinue Mechanical Ventilation: Winning the Balance Between Respiratory Muscle Dysfunction and Mechanical Load

Respiratory muscle function restores over time as the burden of ARF lessens. Active training of the respiratory muscles by imposing loads (e.g., decreasing the trigger sensitivity) has not been established to be effective and may be detrimental if the patient reaches a level of fatigue. On the contrary, reducing the load is generally feasible and can be monitored at the bedside by repeated measurements of respiratory mechanics. Pharmacologic treatments for both resistive and elastic ventilatory loads have been reviewed earlier in the chapter and include standard treatment of bronchospasm, pulmonary edema, tracheobronchitis, and pneumonia. Surveillance of extra-respiratory pathology will also benefit. For example, myocardial ischemia may occur in patients with abnormal coronary physiology when increased O2 consumption by the myocardium may occur during trials of decreased ventilatory support because of the need for extra oxygen consumption, and this may trigger acute myocardial dysfunction and pulmonary edema [88].

Evaluating Readiness

A major success in the process of weaning from mechanical ventilation has been the introduction of daily evaluation of readiness for breathing unassisted [89]. Screening criteria for breathing unassisted include:

Evidence of sufficient stabilization of the ARF episode

Adequate oxygenation by a combination of O2 saturation, FiO2, and PEEP

Ability to consistently trigger the ventilator generating acceptable minute ventilation on a modest level of support

Stable clinical direction, e.g., no recurrent myocardial ischemia or congestive heart failure, no untreated foci of sepsis that could precipitate significant instability, no major delirium, no ongoing bleeding, etc.

The Spontaneous Breathing Trial (SBT)

Practically, screening for readiness is often carried out prior to morning rounds by the respiratory/nursing staff, and performance of the SBT occurs during or after rounds to have people available to survey the patient’s performance. SBTs should be carried out on no support to best mimic unsupported breathing; however, the endotracheal tube may impose additional resistive load, which is often offset by adding a modest level of support, e.g., 5 cmH2O inspiratory pressure and 5 cmH2O PEEP; why 5 of PEEP is added remains unclear to the authors. Variability is also accepted in the duration of the SBT, between 30 min for a patient with little risk of failure and 90–120 min for a complex patient who has failed previous SBTs [90]. SBTs are diagnostic tests, not therapeutic interventions: the evidence available on the usefulness of SBTs is limited to their role immediately preceding extubation, which cannot be attributed to muscle training.

How to Get to a Successful SBT

For the longest time, clinicians have had their own ways of weaning, but very little evidence has supported the use of one mode of ventilation over another. Over the past two decades, two strategies have emerged as the main available options.

Progressive withdrawal of ventilatory support, generally as pressure support ventilation ([PSV], Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_26). PSV allows the patient to control the breathing pattern to a degree superior to any other mode and has become the most frequently used weaning mode [1]. Once a low level of PSV has been reached, a SBT is performed once or twice daily, and, if passed, the patient is ready to be separated from the ventilator.

Progressive lengthening of unsupported breathing during assist-control ventilation ([AC], Chap. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_26) mode, allowing assisted breathing but without progressive withdrawal. When judged appropriately by the clinician, the ventilator is removed. Supporters of this way of weaning claim superiority because it allows direct inspection of the patient without the confusing addition of PSV [91]. This method should allow shorter weanings (PSV would mask the ability to discontinue the ventilator earlier) and higher success rate (a low level of PSV would mask the inability to sustain unassisted breathing).

Data exist to support either method. In both methods, careful inspection of the patient is key to avoid fatigue. While the controversy is open, it seems that each of these two methods works best in the hands of their own supporters.

Failure to Wean: Prolonged Respiratory Failure and the “Chronically Ventilated Patient”

10–15 % of patients with ARF that do not pass one or more SBTs generally receive a tracheotomy and remain dependent on mechanical ventilation for weeks or months. This population of chronically ventilated patients constitutes the bulk of the “chronically critically ill” [92]. This is a newly identified cohort of patients that remains in the “system” during and after their ICU course, generally mechanically ventilated or dependent on other invasive therapies such as renal replacement therapy or ventricular assist devices for heart failure. Discussion relevant to the care of the chronic critically ill can be found in Chaps. 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_62 and 10.1007/978-3-319-19668-8_63. The chronically ventilated patient tends to have high comorbidity and prolonged stays in acute and rehabilitation hospitals, with repeated setbacks that carry him/her back to a higher level of care. When mechanical ventilation lasts for a few months past the initial ICU stay, the rate of non-weaning approaches is 100 %, and the mortality at 1 year is as high as 75 % [75, 76].

Contributor Information

John M. O'Donnell, Phone: 7817448014, Email: John.M.ODonnell@lahey.org

Flávio E. Nácul, Email: fnacul@uol.com.br

Luca M. Bigatello, Email: lbigatello@gmail.com.

Rae M. Allain, Email: Rae.Allain@Steward.org.

References

- 1.Esteban A, Ferguson MD, Meade MO, Frutos-Vivar F, Apezteguia C, Brochard L, et al. Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:170–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-893OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent J-L, Aka S, de Mendonca A, Haji-Michael P, Sprung C, Moreno R, et al. The epidemiology of acute respiratory failure in critically ill patients. Chest. 2002;121:1602–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linko R, Suojaranta-Yilnen R, Karlsson S, Ruokonen E, Pettila V, FINNALI study Investigators One- year mortality, quality of life, and predicted life-time cost-utility in critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure. Crit Care. 2010;14:R60. doi: 10.1186/cc8957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masclans JR, Roca O, Munoz X, Pallisa E, Torres F, Rello J. Quality of life, pulmonary function, and tomographic scan abnormalities after ARDS. Chest. 2011;139:1340–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados M, Al-Saidi F, et al. One- year outcomes of survivors of ARDS. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after ARDS. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, Krauseneck T, Stoll C, Schelling G. Posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:45–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopkins R, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orma JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality of life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenfeld GD, Herridge MS. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute lung injury. Chest. 2007;131:554–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mead J, Agostoni E. Dynamics of breathing. In: Fenn WO, Rhan H, editors. Handbook of physiology, section 3. Washington, DC: American Physiologic Society; 1964. pp. 411–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National asthma education and prevention program. 2007. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf.

- 12.Dougherty RH, Fahy JV. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation- prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chipps BE, Zeiger RS, Borish L, Wenzel SE, Yegin A, Hayden ML, et al. Key findings and clinical implications from the Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: outcomes and treatment regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:332–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendergraft TB, Stanford RH, Beasley R, Stempel DA, Roberts C, McLaughlin T. Rates and characteristics of intensive care unit admissions and intubations among asthma-related hospitalizations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louie S, Morrisey BM, Kenyon NJ, Albertson TE, Avdalovic M. The critically ill asthmatic- from ICU to discharge. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;43:30–44. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8274-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nunn JF. Applied respiratory physiology. 4. Oxford UK: Butterworth, Heinemann; 1993. pp. 256–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimball WR, Leith DE, Robins AG. Dynamic hyperinflation and ventilator dependence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:991–5. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marini JJ. Ventilator- associated problems related to obstructive lung disease. Respir Care. 2013;58:138–47. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aubier M, Murciano D, Milic-Emili J, Touaty E, Daghfous J, Pariente R, Derenne JP. Effects of the administration of O2 on ventilation and blood gases with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:747–54. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutlu GM, Factor P, Schwartz DE, Sznajder JI. Severe status asthmaticus: management with permissive hypercapnea and inhalation anesthesia. Crit Care Med. 2012;30:477–80. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gluck EH, Onorato DJ, Castriotta R. Helium–oxygen mixtures in intubated patients with status asthmaticus and respiratory acidosis. Chest. 1990;98:693–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tajimi K, Kasai T, Nakatani T, Kobayashi K. Extracorporeal lung assist for patient with hypercapnea due to status asthmaticus. Intensive Care Med. 1998;14:588–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00263535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. Updated 2013. http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2013_Feb20.pdf.

- 24.Criner GJ. Ambulatory home oxygen: what is the evidence for benefit, and who does it help? Respir Care. 2013;58:48–62. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Mullerova H, Thal-Singer R, ECLIPSE Investigators et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bach PB, Brown C, Gelfand SE, McCroy DC. Management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a summary and appraisal of published evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:600–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, Collins D, Gross NJ, Light RW, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1941–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, National Emphysema Treatment Trial Group et al. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med. 2003;248:2059–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boldrini R, Fasano L, Nava S. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:48–53. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834ebd71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess DR. Noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Respir Care. 2013;58:950–69. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanch L, Bernabé F, Lucangelo U. Measurement of air trapping, intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure and dynamic hyperinflation in mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care. 2005;50:110–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ARDS Definition Taskforce Acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubenfeld G, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, et al. Incidence and outcome of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gattinoni L, Pesenti A, Bombino M, Baglioni S, Rivolta M, Rossi F, et al. Relationship between lung computed tomography density, gas exchange, and PEEP in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:824–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slutzky AS, Ranieri VM. Ventilator- induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2126–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zapol WM, Jones R. Vascular component of ARDS. Clinical pulmonary hemodynamics and morphology. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:471–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess DR, Bigatello LM. The chest wall in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:94–102. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f40952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talmor D, Sarge T, Malhotra A, O’Donnell CR, Ritz R, Lisbon A, et al. Mechanical ventilation guided by esophageal pressure in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:295–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator- induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:294–323. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9604014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The ARDS-Network Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1775–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terragni P, Del Sorbo L, Mascia L, Urbino R, Martin EL, Birocco A, et al. Tidal volume lower than 6 ml/kg enhances lung protection: role of extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:826–35. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b764d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grasso S, Mascia L, Del Turco M, Malacarne P, Giunta F, Brochard L, et al. Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:795–802. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris RS, Hess DR, Venegas JG. An objective analysis of the pressure- volume curve in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:432–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9901061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattinoni L, Taccone P, Carlesso E, Marini JJ. Prone position in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Rationale, indications, and limits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1286–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1532CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelosi P, Bottino N, Chiumello D, Panigada M, Gamberoni C, Colombo G, et al. Sigh in supine and prone position during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:521–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-198OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guerin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Gacouin A, Boulain T, Mercier E, Investigators of the PROSEVA Study et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daoud EG, Farag HL, Chatburn RL. Airway pressure release ventilation: what do we know? Respir Care. 2012;57:282–92. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sud S, Sud M, Friedrich JO, Meade MO, Ferguson ND, Wunsh H, Adhikari NKJ. High frequency oscillation in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferguson ND, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Mehta S, Hand L, Austin P, Investigators of the OSCILLATE Trial et al. High- frequency oscillation in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:795–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young D, Lamb SE, Shah S, MacKenzie I, Tunnicliffe N, Lall R, Investigators of the OSCAR Study et al. High- frequency oscillation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:806–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meduri GU, Headley AS, Golden E, Carson SJ, Umberger RA, Kelso T, et al. Effect of prolonged methylprednisolone therapy in unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:159–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, Hough CL, Lanken PN, Hyzy R, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1671–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossaint R, Falke KJ, Lopez F, Slama K, Pison U, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide for the adult respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:399–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302113280605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bigatello LM, Hurford WE, Kacmarek RM, Roberts JD, Jr, Zapol WM. Prolonged inhalation of low concentrations of nitric oxide in patients with severe adult respiratory distress syndrome. Effects on pulmonary hemodynamics and oxygenation. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:761–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Afshari A, Brow J, Moller AM, Wettersley J. Inhaled nitric oxide for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acute lung injury in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; CD002787. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, et al. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raghavendran K, Pryhuber GS, Chess PR, Davidson BA, Knight PR, Notter RH. Pharmacotherapy of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1911–24. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin GS, Moss M, Wheeler AP, Mealer M, Morris JA, Bernard GR. A randomized, controlled trial of furosemide with or without albumin in hypoproteinemic patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1681–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000171539.47006.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]