Abstract

The effects of 2 weeks of intralesional chondroitinase abc (ch'abc) treatment on anatomical plasticity and behavioral recovery are examined in adult cats and compared to results achieved with 4 weeks of treatment following tightly controlled lateral hemisection injuries. Analyses also were completed using 35 cats with a range of hemisection magnitudes to assess relationships between treatment duration, lesion size and functional recovery. Results indicate that both 2 and 4 weeks of treatment significantly increased the number of rubrospinal tract (RuST) neurons with axons below the lesion, but neither affected the number of corticospinal tract neurons. Similarly, both treatment periods also accelerated recovery of select motor tasks, which carries considerable importance with respect to human health care and rehabilitation. Four weeks of treatment promoted recovery beyond that seen with 2 weeks in its significant impact on accuracy of movement critical for placement of the ipsilateral hindlimb onto small support surfaces during the most challenging locomotor tasks. Analyses, which extended to a larger group of cats with a range of lesion magnitudes, indicate that 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment promoted earlier recovery as well as significantly greater targeting accuracy even in cats with larger lesions. Together, these results support the potential for ch'abc to promote anatomical and behavioral recovery and suggest that intraspinal treatment with ch'abc continues to enhance motor recovery and performance beyond the subacute injury period and diminishes the impact of lesion size.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, chondroitinase abc, rubrospinal tract, corticospinal tract, adaptive movement, locomotion, motor recovery, plasticity

Introduction

Studies (Jones et al., 2002, 2003a, 2003b; Morgenstern et al., 2002; Busch and Silver, 2007; Galtrey and Fawcett, 2007; Bradbury and Carter, 2011), including our own (Lemons et al., 1999; Tester and Howland, 2008), have shown that after spinal cord injury (SCI) there is an increase in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) and their chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan (CS-GAG) chains at the lesion site. In particular, the CS-GAGs are potent inhibitors of axonal growth and play a role in preventing plasticity necessary for functional recovery (Snow et al., 1990; Smith-Thomas et al., 1994; Zuo et al., 1998). Removal of these CS-GAGs, using the bacterial enzyme chondroitinase abc (ch'abc), has been shown in rat (Bradbury et al., 2002; Grimpe and Silver, 2004; Barritt et al., 2006; Houle et al., 2006; Cafferty et al., 2008) and cat (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011) models of SCI to enhance behavioral recovery and/or axonal growth. In the cat, ch'abc effects have been tested previously only with a 4 week delivery period (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). Results from those studies were striking and supported translation across species with regards to the potential for ch'abc to affect motor recovery. Because cats showed some features of recovery by 2 weeks, including accurate targeting on a horizontal ladder, we hypothesized that similar effects on long-term motor function and anatomical plasticity could be achieved with a shorter treatment period of 2 weeks. The benefits of shortening the treatment period include: decrease of any side effects associated with repeated isoflurane exposure (Creeley et al., 2014) used during treatments, as well as a reduction in treatment costs. The cat model is beneficial to these studies due to the range of basic to skilled locomotor tasks that can be easily trained and assessed, as well as the motor precision that can be assessed on challenging tasks.

In the current study, the effects of ch'abc treatment across 2 weeks are compared to reported results on rubrospinal tract (RuST) plasticity and motor control following 4 weeks of treatment (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). Plasticity of the corticospinal tract (CST), not previously assessed in the ch'abc treated cat, also was examined and is presented and compared across treatment durations. Due to the fact that prior feline studies, as well as the current 2 week treatment study, have used inclusion criteria to minimize lesion variability, the final set of analyses in this study compared results from 35 animals with a range of lesion sizes. The purpose of this final aspect of the current report was to determine if there are interactions between treatment duration and hemisection magnitude which would suggest that the impact of ch'abc treatment upon recovery is influenced by variations in lesion size.

Materials and Methods

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals and were approved by both the VA Medical Center and University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Animals used across the various aspects of the current study, along with the general experimental paradigm, are presented in Figure 1. Twelve cats (6 ch'abc treated, 6 control) with similar hemisection magnitudes were used in the initial aspects of this study to assess the effects of 2 weeks of ch'abc treatment. These 12hemisections were similar to each other (Figure 2), and comparable to those reported in our prior studies assessing a longer treatment period (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). All 12 animals were trained 5x/week on a range of simple to challenging locomotor tasks and used in the behavioral aspects of the study. Eight of the 12 (4 vehicle control and 4 ch'abc treated), which met the following Fluorogold (FG) inclusion criteria, were included in the cell count aspects of the study: 1) FG labeling across the entire cross-sectional extent of the spinal cord, particularly in the ipsilateral and contralateral dorsolateral funiculi ; 2) no tracer spread into the lesion site; 3) FG-labeled neurons in the non-axotomized RN or MC which are easily detectable at 20X. Due to section loss during cutting in 2 of the 8 animals (1 from each group), one was excluded from red nucleus (RN) cell counts and the other from motor cortex (MC) cell counts.

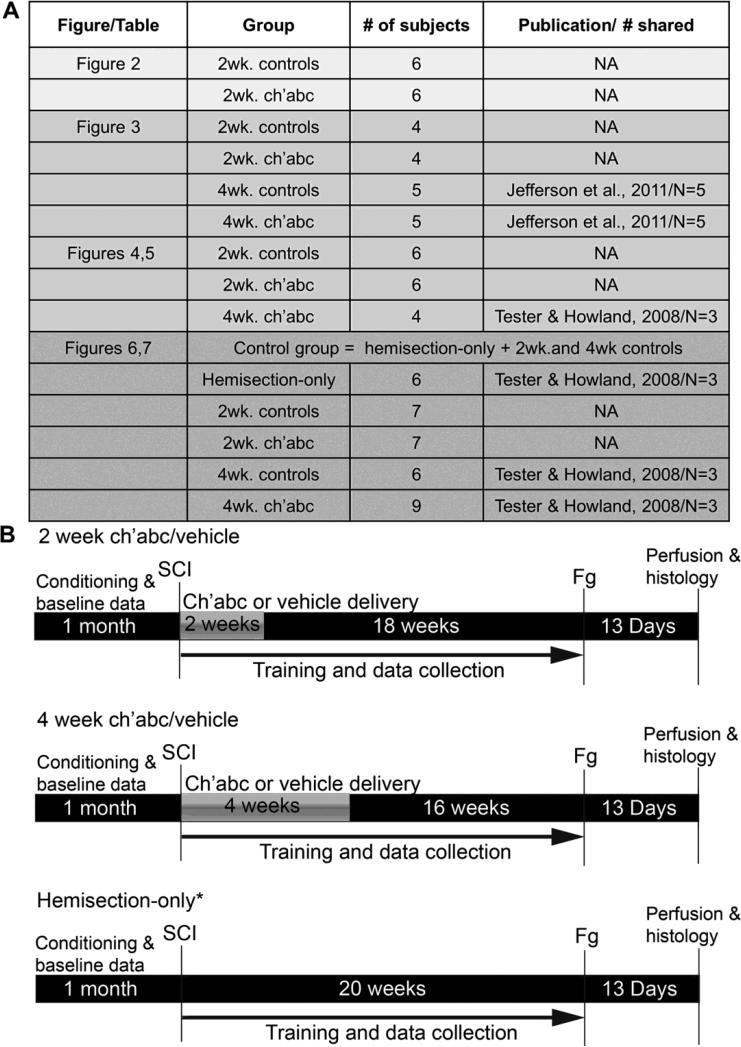

Figure 1.

Description of subjects and experimental paradigm. Some comparisons are made with subjects from prior publications. (A) We describe subjects that are assessed in each figure in the Results. If animals were from a prior publication, the publication is cited and the number of subjects used from that publication indicated. “NA” indicates a group did not include any animals from prior publications. Timelines of experimental procedures are also outlined (B). * indicates the group is used only for the lesion-magnitude correlations in Figures 6 and 7.

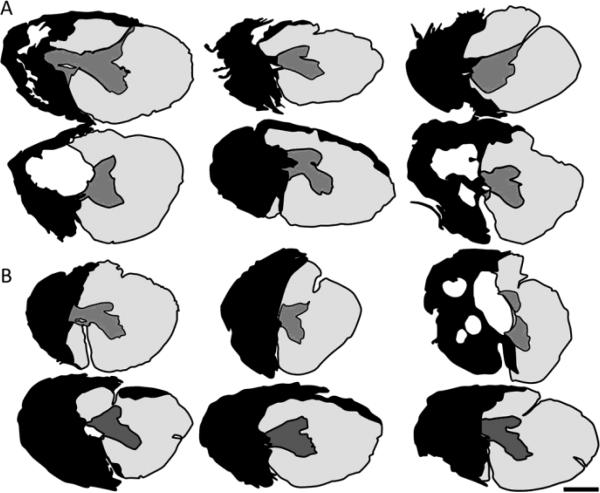

Figure 2.

Range of spinal hemisections. A-B, Drawings indicating the extent of each animal's lesion based upon multiple horizontal histological sections through the lesion segments of each control (A) and each 2 wk ch'abc, treated (B) animal are shown. The entire length of each animal's lesion was sectioned at 25 μm and every 10th section stained with cresyl violet and myelin dye. The greatest amount of damage in all gray and white matter regions was determined across sections for each animal and then collapsed into the single drawing shown to represent that individual animal's lesion. Black indicates frank areas of tissue loss, scarring and absence of myelin. Scale bar, 1mm.

In addition to cats treated for 2 weeks, counts of CST neurons were conducted by cutting and processing banked tissue from 9 cats treated for 4 weeks with either ch'abc (n=4) or vehicle control (n=5) (Jefferson et al., 2011). These cats were prepared like the 2 week treated cats with the exception of the lengthened treatment period. Further, tissue processing was identical to, and done in parallel with, that of the 2 week treatment group.

To determine the effects of lesion magnitude, 35 cats with varying lesion sizes across three groups were used: no ch'abc (lesion-only or control treatment; n=19), 2 weeks of treatment (n=7), and 4 weeks of treatment (n=9). This included some cats from Tester and Howland, 2008. These 35 cats were chosen from our laboratory databank based upon their training protocols. Training, with regards to number of crossings and practice frequency per week of each skilled task, were similar to the approach described for the 2 week treatment groups (below). This determination was made based upon review of daily training records and behavioral notations. For a full description of the subjects used in each figure refer to Figure 1.

Subjects

All cats were Class A, purpose bred, SPF, spayed, adult, females. Spays were performed to prevent any hormonally based changes during the study (Sribnick et al., 2003, 2005). Data from a total of 35 cats will be described and are used across the different aspects of this report. Cats specifically used to assess the 2 week treatment period were placed into one of two groups: 2 week control (n=6) or 2 week ch'abc (n=6). At the beginning of the study, animals were conditioned to perform five locomotor tasks for food rewards: bipedal hindlimb stepping on a treadmill at 0.5m/s and crossing of a basic (30.5 cm wide) walkway, a horizontal ladder, a narrow (5 cm wide) beam, and a peg walkway. Each of the 4 crossing tasks were 3.7 m long. This report focuses only on these four tasks which require voluntary as well as intraspinal aspects of neural control. Training continued throughout the study as in Tester and Howland (2008). Once cats were able to consistently perform the tasks, they were filmed for baseline data collection. Following injury, training resumed and performance data was collected across five months. After the completion of the behavioral aspects of the study, cats received intraspinal FG injections caudal to the lesion site for retrograde tract tracing. Thirteen days later, cats were transcardially perfused and tissues collected for assessments of lesion morphology and axonal plasticity.

Low thoracic spinal hemisection and subcutaneous port implantation for ch'abc delivery

Prior to surgery, cats received 0.1 cc atropine sulfate (0.04 - 0.06 mg/kg, subcutaneously) and 0.1 cc acepromazine (0.4 – 0.5 mg/kg, subcutaneously). Isoflurane (1-3.5%) was used for anesthesia and intravenous fluids (lactated ringers, 10ml/kg/h) were administered for maintenance of hydration. Respiratory and heart rate, expired CO2, SPO2, body temperature, and general plane of anesthesia were monitored closely. Surgical procedures are similar to those described in detail in Tester and Howland (2008). Briefly, all cats received a left, T10 spinal hemisection created by iridectomy scissors. Following hemisection, an injectable port body (Solomon Scientific, San Antonio, TX) was placed in the subcutaneous space by securing it to the left dorsolateral trunk musculature using VetBond (Patterson Veterinary, St. Paul, MN) and 4-0 Vicryl suture. The port tubing was secured along the back muscle using loose sutures and its tip placed at the lesion site. To maintain the tip position, Vetbond was used to secure the tubing to the left, caudal lamina adjacent to the lesion site. The tubing tip was further anchored by closing the dura around the tip with 8-0 Prolene. Protease free ch'abc (1 U/200 μL vehicle) (Seikagaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), or vehicle (sterile saline or Tris-HCL) was injected through the port system prior to placing the final sutures to close the dura. This purged the system of air, verified that the port was patent, and provided the first treatment dose. Durafilm and gelfoam were placed over the dural sutures followed by closing of the muscle (2-0 Dexon II), subcutaneous layer (2-0 Dexon II), and then skin (3-0 Dexon II). Buprenorphine (0.03 cc/kg, ~every 8 hours) was given for 48 hours post-injury and the bladder emptied using the Crede method until voluntary voiding recovered (typically < 3 days). Cats were housed on thick foam cushions for the remainder of the study. Basic care procedures are described in depth in previous studies (Howland et al., 1995a, 1995b).

Chondroitinase ABC administration

Prior to use, ch'abc enzymatic activity was tested and confirmed with fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (FACE) as previously described (Tester et al., 2007). Ch'abc (0.25 U in 50 μL of vehicle) or vehicle (50 μL saline or tris-HCL) injections began the day cats were injured and continued every other day for 2 weeks for a total of 7 treatments. These cats are compared with cats from our prior studies that received 4 weeks of injections for a total of 15 injections (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). Injections of the 50 μL volumes were made across a ten minute period using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Cats were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane during the injections.

Fluorogold spinal injections

After final behavioral data was collected, cats in the tract tracing portion of the study underwent a second surgery to receive intraspinal injections of the retrograde tracer FG caudal to the lesion site. Details of the tracing procedure are as described in Jefferson et al. (2011). In brief, 0.5% FG (Fluorochrome, LLC, Denver, CO) was mixed in sterile, de-ionized water in an aseptic hood the morning of the procedure and kept on ice in a sterile eppendorf tube prior to use. Under the same anesthesia protocol described for surgery above, the lesion site was partially re-exposed in order to locate the most caudal dural stitch made during the initial surgery. The spinal cord, ~13 mm caudal to this suture, was then exposed for FG injections. Four injection sites were identified on the dorsal surface: medial to the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) and lateral to the DREZ on the right and left spinal hemisphere, all in a staggered formation. Using a micromanipulator, a 33 gauge Hamilton needle was inserted into each site. Two FG deposits of 0.25 μL were made in each needle track for a total of 2 μL across the 4 needle tracks. The first deposit was made in the ventral half, and the second in the dorsal half of the spinal cord. Durafilm and gelfoam were placed over the entire area exposed by the laminectomy, which included the injection sites, and the muscle, subcutaneous and skin layers closed. A post-injection survival period of 13 days allowed sufficient time for FG to travel to the RN and MC. Post-op care is the same as described for spinal hemisections.

Behavioral tasks and training paradigm

Prior to surgery, cats were conditioned to perform locomotor tasks for food rewards. Cats were trained 5x/week and each day training included bipedal stepping on a treadmill as well as 1-2 other tasks (see above), which were alternated equally across days. Within 48 hours following SCI, training was reinitiated. Acutely post-injury, cats primarily were trained on the treadmill and basic runway due to limited motor capabilities. The skilled tasks frequently were attempted and then integrated as quickly as some potential to practice was shown.

Assessment of locomotor recovery

A daily log was kept of each animal's overall performance including when cats recovered the ability to perform a task after injury. This referred to the first day three independent crossings, consecutive or non-consecutive, were achieved. When cats were unable to recover a task they were assigned a “150” day recovery period, which is the total number of days cats were engaged in the behavioral portion of the study. Animals were filmed on each locomotor task using a Peak-Vicon 3D pan and tilt system (Vicon, Englewood, CO). Filming occurred prior to injury (normal baseline), as well as multiple times following SCI (2, 4, 8, 16 and 20 weeks). Using frame by frame analyses, the percentage of times a cat was able to accurately place its ipsilateral hindlimb paw onto the “walkway” surface was calculated for the horizontal ladder, narrow beam and peg walkway. This is the hindlimb ipsilateral to the injury site, which shows the greatest motor deficits. Further, the accurate placement of paws onto smaller surfaces requires supraspinal input (Beloozerova et al., 2010; Stout and Beloozerova, 2013) and is more difficult to recover after injury compared to more gross aspects of movement (e.g. weight support, alternating steps). Accurate placement percentage is calculated from the 3 best crossings during each task at each time point. If unable to cross or place their ipsilateral paw, a score of 0% was assigned for placement accuracy for the task. The percentages were averaged for each group to allow comparison across groups.

Perfusions and tissue preparation

At 13 days following FG injections, cats were deeply and rapidly anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, >40 mg/kg, i.p.). Supplemental doses were given i.v. as needed to ensure that animals were deeply sedated. Once sedated, an intravenous injection of 1 cc heparin (10,000 U) was given, followed by 1 cc of 1% sodium nitrite (i.v.) 20 minutes later. Immediately after, cats were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The spinal cord and brain were dissected, blocked, post-fixed in 30% sucrose and 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) and stored at 4°C until cut. The lesion, injection site, and rostral midbrain were cut on a cryostat in 25 μm thick sections, while the MC was cut at 40 μms, into 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2, 0.9% saline) and kept at 4°C.

Cresyl violet and myelin staining

In brief, every 10th section of the lesion site was mounted onto slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) coated with chrom-alum and poly-L-lysine layers (chromium potassium sulfate and poly-L-lysine, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; gelatin, Fisher Scientific). Tissue was fume fixed on the slides with 4% paraformaldehyde to enhance adherence. Tissue was first dipped in dH2O, and then dehydrated in increasing increments of alcohol (70%, 95%,100%). After immersing in xylene (10 minutes), tissue was rehydrated in decreasing increments of alcohol, then water and placed in an aqueous myelin dye (Eriochrome Cyanine R; Fluka, St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes. After washing in water, differentiation took place in 1% ammonium hydroxide (1 minute). Tissue was then placed in 0.5% cresyl violet (cresyl violet with acetate, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 3 minutes, washed thoroughly in water, immersed in 70% alcohol, and then differentiated using < .2% glacial acetic acid in 95% alcohol. Following this, tissue was dehydrated again in increasing increments of alcohol, immersed in xylene and coverslipped with DPX (Fluka, St. Louis, MO).

Assessment of injection sites

Every 40th section of each FG injection site was mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and coverslipped with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY). Sections were assessed using fluorescent microscopy to ensure that each animal used in cell count analyses met inclusion criteria.

Immunohistochemistry

Every 8th section (200 μm) through the RN, and every 40th section (640 μm) through the MC were processed using the polyclonal anti-FG antibody (1:10,000, Fluorochrome, LLC, Denver, CO). Sections first were quenched (30% H2O2 and PBS) for 30 minutes, followed by 2, 10 minute rinses in 1% goat serum in PBS containing 0.4% Triton X-100 (1% S-PBS-T). Tissue was then blocked in 5% S-PBS-T for 1 hour and incubated in anti-FG antibody overnight at room temperature. The next day, tissue was rinsed in 1% S-PBS-T and incubated in 5% biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody made in goat (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour. After a second rinse with 1% S-PBS-T, tissue was incubated in the avidin-biotin complex (ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Following this incubation tissue was rinsed with PBS, then reacted with 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 9 minutes. The DAB reaction was stopped with a PBS rinse. Tissue was subsequently mounted onto chrom-alum and poly-L-lysine coated slides, allowed to dry and then fume fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 1 hour. Tissue was then dipped in water, dehydrated in alcohol (increasing concentrations), placed in xylene for a total of 10 minutes and coverslipped with DPX (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Fluorogold-labeled cell counts

FG-labeled neurons of each stained section of the RN and MC were counted using a 20X microscope objective on a Zeiss or Nikon microscope. Only those neurons with visible, complete soma were included in the counts. The non-axotomized (left) cell counts were kept separate from the axotomized (right) cell counts and each assessed as absolute numbers. Additionally, the axotomized cell counts were assessed as percentages of the non-axotomized cell counts, which is a traditional approach to control for internal differences between animals (tracer uptake, tissue processing, etc).

Criteria for lesion ranking of 35 cats

Due to our strict lesion size inclusion criteria in prior reports, the effect of chondroitinase on over - or under - hemisection lesions were not assessed. Although this control of lesion size in our published studies allowed for a clearer understanding of the ch'abc treatment effect on function and anatomy, it also prevented an understanding of chondroitinase's effectiveness across different lesion magnitudes. Here, we compare functional recovery in 35 cats with a range of lesion sizes, from under- to over-hemisections, that received the same training protocol and either 2 (n=7) or 4 weeks (n=9) of ch'abc, vehicle (n=14), or an injury-only (n=5). Both the vehicle control and hemisection-only cats were combined into a single group (n=19) for analyses. Three scientists blinded to treatment groups, ranked lesions based on the amount of total spared tissue. A score of 1 indicated the least amount of spared tissue and 35 the greatest amount. Lesions that appeared extremely similar could be given the same value (ranked equally). Rank sets were compared to ensure that rankings were relatively similar and that the three individuals properly understood and performed the task. The three assigned ranks for each lesion were then averaged and correlated against the recovery onset of each of the five tasks, as well as the percentage of accurate ipsilateral hindlimb placements at 4, 8, and 16 weeks post-injury. In some cases, the individual values for each cat on a given task/time point were compared across groups. These cats were separated into the “larger lesions” category if their ranking was ≥ 16 and/or the “higher functioning” group if their functional score was less than the average for task onset. The same was true of cats that had a ranking of ≥ 16 and/or a higher score than the average for limb accuracy. These groups are demarcated with different boxes when presented in figures.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel's Analyse-it statistical software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and Statistic Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). The Mann Whitney U test was used to assess group differences and was corrected for ties, while the Binomial proportions test was used to compare proportions of cats across groups. The specific p-values for the Binomial proportions test were determined using equations from the textbook Statistics by William Hays (Hays, 1981). The Spearman rank correlation was used to correlate lesion rank and behavior. The value of p was set at p<.05 for all tests. Comparisons were considered to be “trends” if the p value fell between .05 and .10.

Results

Lesion magnitude in groups treated for 2 weeks

The general extent of injury was determined from cresyl violet and myelin stained sections. Twelve cats with similar lesions were used to assess the effects of 2 weeks of ch'abc treatment (n=6) versus control treatment (n=6) on anatomical and behavioral recovery. These lesion magnitudes were virtually identical to those used in our prior publications using a longer treatment regimen (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). Figure 2 shows the lesions for the control (Figure 2A) and 2 week ch'abc treated groups (Figure 2B). Lesion variations were relatively minimal, ranging from minor ipsilateral sparing to some contralateral damage.

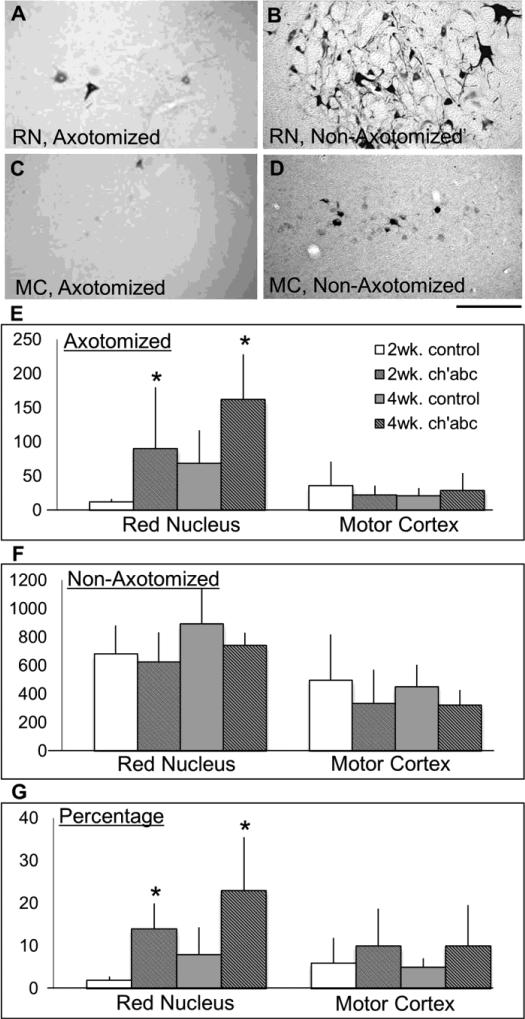

Number of red nucleus, but not motor cortex, neurons significantly increases with ch'abc

Both the RuST and CST tracts contribute to control of movement patterns required during adaptive forms of locomotion (Beloozerova and Sirota, 1993; Lavoie and Drew, 2002; Pettersson et al., 2007; Morris et al., 2011). Thus, due to the use of several tasks requiring significant adaptability of limb trajectories in the current study (horizontal ladder, narrow beam, peg walkway), these anatomical systems were targeted for assessment. Neuronal counts show that the number of retrogradely labeled neurons in the axotomized RN are significantly greater in the 2 week ch'abc treated group than in their control counterparts (Figure 3A,E; Mann-Whitney U test, p=.03). These ch'abc-mediated effects indicate that more axotomized RN neurons have axons extending below the lesion level. This result is clear regardless of whether absolute neuronal counts are used, or if the number of labeled neurons is presented as a percentage of the non-axotomized nucleus (Figure 3A,G; Mann-Whitney U test, p=.03). The benefit of assessing as a percentage is that it controls for differences across animals by allowing the non-axotomized nucleus to serve as an internal control. The number of FG-labeled neurons also was compared across all non-axotomized nuclei and showed no significant differences between the 2 week ch'abc and 2 week control treatment groups. The current results showing a significant increase in labeled RN neurons in the axotomized nucleus of cats treated for 2 weeks with ch'abc are very similar to those shown following 4 weeks of treatment (Jefferson et al., 2011). Although counts were somewhat higher and conducted by another individual in the prior study on 4 weeks of treatment (Jefferson et al., 2011), comparison across the two ch'abc groups showed no significant differences across the axotomized nuclei (Figure 3A,E; Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.40) as well as the non-axotomized (control) nuclei cell counts across all four groups1 (Figure 3B,F; Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.20) suggesting the consistency of the tract tracing techniques and the effectiveness of 2 weeks of treatment on the RN response.

Figure 3.

Supraspinal neurons with axons below the lesion. Using tissue sections, the numbers of fluorogold labeled neurons were determined for the non-axotomized and axotomized red nuclei (RN) and motor cortices (MC). The axotomized red nuclei (A), and motor cortices (C), had fewer labeled cells than the non-axotomized red nuclei (B) and motor cortices (D). Average neuronal counts for the axotomized (E) and nonaxotomized sides (F), and percentage (G) of labeled neurons in the axotomized relative to non-axotomized sides for the 2 and 4 week control groups, as well as the 2 and 4 week chondroitinase abc (ch'abc) groups are shown. The red nuclei counts for 4 week control and chondroitinase abc treated cats were previously reported (Jefferson et al., 2011; see footnote). *, p<0.05 between ch'abc and respective control groups as determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. Standard deviations are shown. Scale bar = 100 μm with the dorsal side oriented at the top of the figure.

No significant differences were found in the number of FG-labeled neurons in the axotomized MC across the four groups regardless of treatment or length of treatment (Figure 3C,E). The same is true for the non-axotomized MC (Figure 3D,F).

Rate of recovery following 2 weeks treatment

Voluntary motor function of the hindlimb ipsilateral to the lesion was severely disrupted during the first 1-2 days after injury in all cats studied. In contrast, the contralateral hindlimb showed active voluntary movement within a few hours of surgery. Many cats quickly showed some capacity (within a day) to support their hindquarters with this limb - although the limb posture was consistently flexed. Those that did not regain this capacity during the first day, did so by ~2 days. This general motor progression is consistent with prior studies in the cat using the hemisection model (Eidelberg et al., 1986; Helgren and Goldberger, 1993; Kuhtz-Buschbeck et al., 1996; Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). There were no significant differences between the control and ch'abc treated groups with respect to this very early progression or the timing of this recovery within the first few postoperative days. Additionally, there were no group differences in the time it took to recover the ability to cross the basic runway (control: 3.2 ± 2.4; ch'abc: 1.8 ± 1.0 days). Thus, although involvement of the ipsilateral hindlimb may have been absent or minimal acutely, progression of the animals’ ability to cross a walkway on primarily three limbs and the timing of the ipsilateral hindlimb's general integration post-injury was similar across groups during this relatively simple walking task.

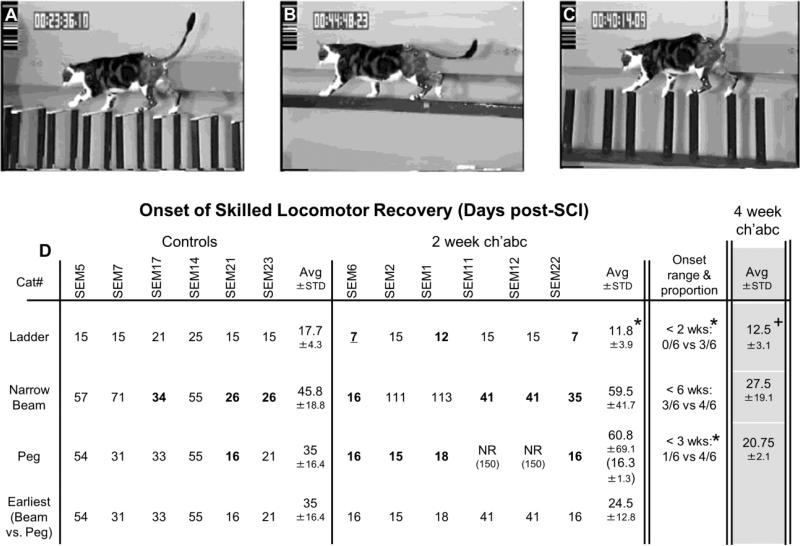

The ability to cross the horizontal ladder, peg walkway, and narrow beam, took longer to achieve post-injury than walking on the basic runway. This is not surprising due to the greater demands for descending supraspinal input (Beloozerova et al., 2010). Notably, cats treated with 2 weeks of ch'abc showed accelerated recovery. On average, cats treated for 2 weeks with ch'abc recovered the ability to cross the horizontal ladder task at 12 days post-injury which is significantly earlier than controls by approximately a week (Figure 4D; Mann-Whitney U test, p=.03). When the proportion of cats from each group that was capable of crossing the horizontal ladder before the 2 weeks post-injury time point, was significantly greater in the ch'abc group (3/6 cats) treated for two weeks compared to controls (0/6 cats, Figure 4D; Binomial proportions test, p=.01). Further, the earlier timing with respect to recovery following 2 weeks of ch'abc treatment is the same as seen in cats treated for 4 weeks. Specifically, cats treated with ch'abc for 4 weeks also recovered the ability to cross horizontal ladder significantly earlier than controls (Figure 4D; Mann-Whitney U test, p=.02) and were not significantly different from animals treated for only 2 weeks with ch'abc.

Figure 4.

Onset of skilled locomotor recovery. The specific day each 2 week control and chondroitinase abc (ch'abc) treated animal recovered the ability to cross the horizontal ladder (A), narrow beam (B), and peg walkway (C) are shown in addition to the averages and standard deviations for each group. The proportion of cats capable of recovering each task within specified ranges also are listed. The average onset periods and standard deviations for 4 week ch'abc treated cats from previous work (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011) are included in the right column for comparison. Images (A-C) show a non-injured animal on each task. (D), 2 week ch'abc treated cats began crossing the ladder significantly earlier than controls (11.8 vs. 17.7 days) and at the same time point as the 4 week ch'abc treated group. Significant differences also were seen between the proportion of cats from the control vs. 2 week ch'abc treatment groups (“Onset range & proportion”) that were able to recover the ability to cross the horizontal ladder in <2, and the peg walkway in <3 weeks after injury. Cats’ performances that fit these categories are identified with bold numbers. To better understand onset of the two most difficult skilled tasks, narrow beam and peg walkway, the 4th row of data “Earliest of: narrow beam vs. peg walkway”, identifies the earliest day that either of these tasks recovered. The Avg day (24.5) for the 2 week ch'abc group falls between those for the 4 week ch'abc group on narrow beam (27.5) and peg walkway (20.75). * = 2 week ch'abc vs. 2 week control, p=<.05; + = 4 week ch'abc vs. 2 week control as determined using the Mann-Whitney U test for non-proportion comparisons and the Binomials Distribution Test for comparisons of proportions. Avg=average; STD=standard deviation, NR=never recovered and scored as 150 days.

In contrast to the ladder, crossing the peg walkway is much more difficult and took longer than 2 weeks to recover. When the proportions of cats that recovered the ability to cross the peg walkway in <3 weeks are compared, the 2 week ch'abc group (4/6 cats) is superior to its control group (1/6 cats; Figure 4D; Binomial proportions test, p=.04). Regardless of the time point, no differences in the proportion of cats between the 2 week ch'abc and control treatment groups, were seen with respect to recovery onset on the narrow beam. The time periods to recover the ability to cross the peg walkway and narrow beam were notably more variable across cats than for the ladder task. In the control treated cats, on average, this recovery occurred between 35 and 46 days (6th and 9th weeks) post-injury. When the onset for these two tasks is compared in each individual control cat, the timing appears related (i.e. recovery across tasks occurs within 0-10 days of each other for each cat). However, this is not true for the 2 week ch'abc treated group which shows even greater variability within and across the tasks. In only one 2 week ch'abc treated animal does the timing appear related. This variability within the ch'abc treated group for each task primarily was a result of two cats that never recovered the ability to cross the peg walkway and two others that were very slow to recover crossing of the narrow beam (Figure 4D). If the earliest onset of either of these two difficult tasks is used to represent timing of difficult task recovery, the 2 week control and ch'abc treated groups begin to separate with an average recovery time of 35 +/− 16 d and 24.5 +/− 12.8 d respectively. Interestingly, the average of ~24d for the 2 week ch'abc treated groups falls within the 21-28d average timeframe seen for peg and narrow beam recovery in the 4 week ch'abc treated cats (Figure 4D). This timing is beyond the 2 week, but within the 4 week treatment window.

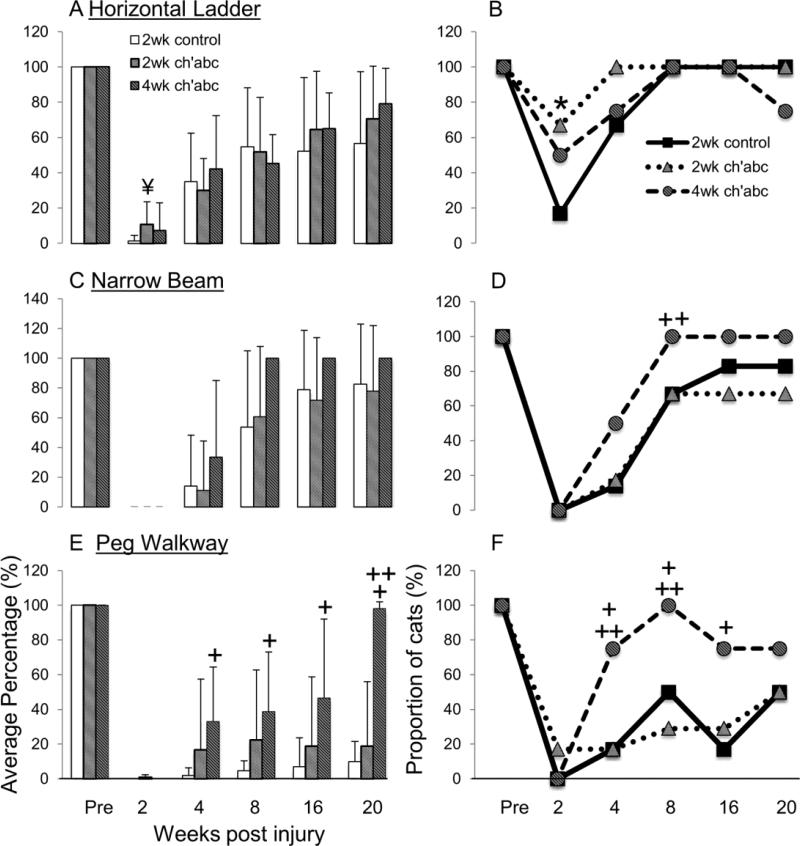

Ipsilateral hindlimb placement accuracy following 2 weeks of treatment

Adaptation of ipsilateral hindlimb movements required to accurately target, place, and maintain the paw on a support surface during more difficult tasks did not show the same robust recovery across groups that stepping movements of the ipsilateral hindlimb did while traversing the basic runway. To challenge and assess the capacity for limb adaptation, which normally involves the RuST and CST (Drew et al., 2002; Lavoie and Drew, 2002; Pettersson et al., 2007; Beloozerova et al., 2010), we used the horizontal ladder, narrow beam and peg walkway. Pre-injury, all cats accurately placed their ipsilateral hindlimb onto ladder rungs, the narrow beam, and pegs 100% of the time (Figure 5). This ability was vastly disrupted by a lateral hemisection. Recovery began first on the horizontal ladder and was accelerated in the ch'abc treated group. Between 2 and 3 weeks post-injury, the proportion of 2 week ch'abc treated animals (4/6 cats) showing some ability to place their ipsilateral paw on the rungs while crossing, compared to control animals (1/6 cats), was significantly greater (Figure 5; Binomial proportions test, p=0.04). Comparison of the percentage of accurate paw placements across groups showed a trend towards a greater number of accurate placements in the 2 week ch'abc treated group (Figure 5; Mann-Whitney U test, p=0.07). This trend was transient, as by 4 weeks the control animals were performing similarly to the 2 week ch'abc group with regards to number of accurate placements on the ladder. This early trend was similar to that seen in 4 week ch'abc treated cats in our previous studies (Tester and Howland 2008, Jefferson et al, 2011). Accurate ipsilateral paw placement took longer to recover on both the narrow beam and peg walkway, in that neither group of cats treated for 2 weeks (ch'abc or control) showed any ability to perform this feature by 2-3 weeks after injury except for a single ch'abc treated cat that placed its ipsilateral paw 1 out of 25 steps (4%) on the peg walkway. Between 4-5 weeks post-injury, 1 cat from each group began to accurately target on both the narrow beam and peg walkway. Across the remainder of the 20 week recovery period, both 2 week control and ch'abc treated cats continued to improve equally and performances were similar across groups. On the peg walkway, one cat from the ch'abc group achieved 100% accuracy, while accuracy in the other cats from both groups ranged from only 7 to 23% and the differences were not significant between groups. These results on control of limb trajectory are one of the greatest differences between the 2 and 4 week ch'abc treatment paradigms. When direct comparisons were made between the 2 week and 4 week ch'abc treated groups, targeting accuracy on peg walkway is significantly greater in the 4 week treatment group at 20 weeks post-injury (Figure 5: Mann-Whitney U Test, p=0.046). Specifically, the proportion of 4 week ch'abc treated cats able to accurately target on peg walkway at 4 (3/4) and 8 (4/4) weeks post-injury was significantly greater than the proportion of 2 week ch'abc treated cats (1/6, 2/6; Figure 5: Binomial proportions test, p=0.05, 0.001). Comparison of results on the narrow beam task were similar and showed that a significantly greater proportion of 4 week treated (4/4) compared to 2 week treated cats (3/6) showed some ability to accurately place on the narrow beam at 8 weeks post-injury (Figure 5: Binomial proportions test, p=0.05). Finally, comparisons with control treated cats showed that a significantly greater proportion of 4 week ch'abc treated cats presented with some ability to accurately target on both the narrow beam (Figure 5: Binomial proportions test, p=0.05) and peg walkway tasks (Figure 5: Binomial proportions test, p=0.05) beginning at 4 weeks post-injury compared to controls, as well as perform significantly better at targeting accuracy on the peg walkway compared to controls at 4, 8, 16, and 20 weeks post-injury (Figure 5; Mann-Whitney U Test, p=0.04, 0.01, 0.04, 0.03).

Figure 5.

Accurate targeting of the ipsilateral hindlimb. The average percentage of times cats were able to accurately target with their left hindlimb onto the surface of a ladder rung (A), narrow beam (C), or peg walkway (E) is presented for control, 2 week ch'abc, and 4 week ch'abc treated groups prior to receiving a low thoracic hemisection (Pre) and at 2, 4, 8, 16, and 20 weeks post-injury (w.p.i). The proportion of cats able to accurately place at least once during a crossing on the ladder (B), narrow beam (D), and peg walkway (F) also are presented. Statistical analyses compared each ch'abc treated group to the control group. The Mann Whitney U Test was used to compare average number of placements between groups and the Binomials Proportions Test was used for comparisons of proportions. * = 2 week ch'abc vs. 2 week control, p<0.05; + = 4 week ch'abc vs. 2 week control, p<0.05; ++ = 4 week ch'abc vs. 2 week ch'abc, p<0.05; ¥,p=0.07.

The relationship between spared tissue and functional recovery

Variability in lesion magnitudes across 35 cats with lateralized lesions

In addition to the 12 cats whose lesions are shown in Figure 2 and whose functional recovery is described above, lesion and performance data from 23 additional cats from the laboratory's database for a total of 35, were used to determine relationships between the amount of spared tissue, functional recovery, and ch'abc treatment. The 35 lesions ranged from very over-hemisected with sparing in only one quadrant (25%) of the spinal cord cross section (Figure 6A), to very under-hemisected with sparing in 3/4ths (75%) of the spinal cord cross section (Figure 6C). Those that were ranked in the middle were near perfect hemisections (Figure 6B). Average ranks for each animal, onset of task recovery, and accurate ipsilateral hindlimb placements on the horizontal ladder, peg walkway, and narrow beam were tested for correlations (Figure 6D). The following final 2 results sections are based on data from these 35 animals.

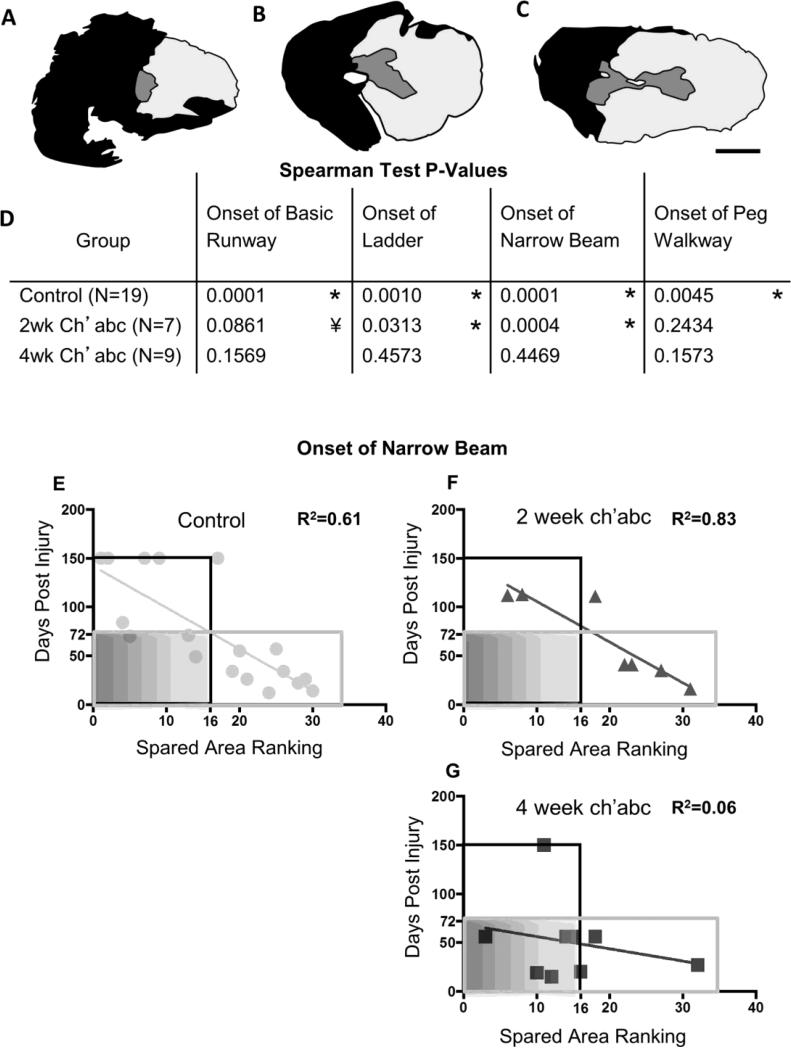

Figure 6.

Task onset and spared tissue correlations. Lesion epicenters were stained with cresyl violet and myelin dye, and then ranked from the least amount of spared tissue (rank=1; A) to the greatest amount of spared tissue (rank=32; C). Some lesions were ranked the same if they had extremely similar amounts of spared tissue. Therefore, the highest ranked lesion is not equivalent to the total number of cats included in the study. The median lesion (rank=16; B), was close to a standard hemisection (scale bar, 1mm). Correlation coefficients were determined for comparisons across lesion rank and the number of days it took animals to recover the ability to cross the basic runway, horizontal ladder, narrow beam, and peg walkway after injury (D). With one exception, significant, or trending towards significant, correlations between lesion size and performance onset were found in the control and 2 week ch'abc treated groups, but none were found in the 4 week ch'abc treated group. For a closer assessment, the ranks and onset day for crossing of the narrow beam for each individual animal are plotted for the control (E), 2 week ch'abc (F), and 4 week ch'abc (G) groups. The black outlined boxes identify those data-points (individual cats) which fall into the “larger lesion” category. Gray outlined boxes demarcate those individual cats that fall into the “high functioning” category which is based on the average number of days it takes for cats in the control group to recover narrow beam (72 days). Therefore, all cats that take less than 72 days are categorized as “higher functioning”. Data points inside the gray shaded boxes demarcate cats with larger lesions and which also are “higher functioning”. Trend lines and the coefficient of determination values (R2) were calculated for each group and task and the p value for each of these is shown in the table with significant correlations (*) and trends (¥) noted. Correlations were determined using the Spearman Test.

Onset of task recovery versus spared tissue rankings

For control animals, there was a significant correlation between spared tissue rank and recovery onset on the basic runway (Figure 6D; Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.77, p=.0001, n=19), horizontal ladder (Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.65, p=.001, n=19), peg walkway (Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.58, p=.005, n=19), and narrow beam (Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.83, p=.0001, n=1;). The 2 week ch'abc treated animals also showed relationships between tissue ranks and recovery onset for horizontal ladder (Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.73, p=.03, n=7), and narrow beam (Spearman rank correlation, rs=−0.95, p=.0004, n=7) performances and a strong trend (Spearman rank correlation, rs=0.32, p=.0861, n=7) toward significance for onset of recovery on the basic runway. In contrast, no correlation was seen with recovery onset of the ability to cross the peg walkway. Strikingly, there were no significant correlations between lesion size and recovery onset on any of the locomotor tasks for the 4 week ch'abc group. The lack of relationships between spared tissue and recovery onset for any of the tasks suggests that 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment decreased the dependence of recovery on the amount of spared tissue for these more adaptive tasks. This is supported by individual values for each animal. As an example, the onset of narrow beam is presented for the control (Figure 6E), 2 week ch'abc (Figure 6F), and 4 week ch'abc cats (Figure 6G). By dividing the data into quadrants indicating amount of tissue sparing and functional level using the average onset of narrow beam recovery for the control group, and the median of the total ranks (32), it is apparent that a greater percentage (67%) of 4 week ch'abc cats fall into the low tissue sparing and high functional recovery quadrant compared to the 2 week ch'abc (0%), and control cats (22%). This same general effect is seen across all tasks indicating that 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment can be an effective therapeutic for larger lesions.

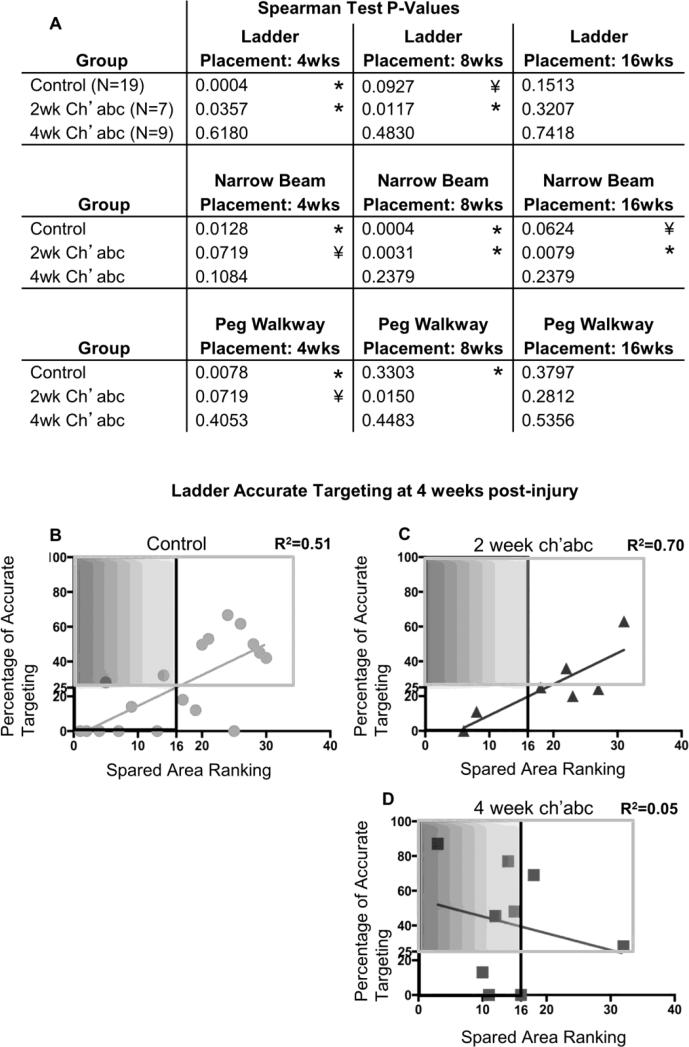

Accurate hindlimb targeting versus spared tissue ranking

The amount of spared tissue in both the control and 2 week ch'abc treated groups either significantly correlated, or strongly trended towards significance, with ipsilateral hindlimb accurate paw placement at 4 weeks post-injury on the horizontal ladder (Figure 7A; Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.70, p=.0004, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.71, p=.04, n=7), peg walkway (Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.55, p=.01, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.61, p=.07, n=7), and narrow beam (Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.52, p=.01, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.61, p=.07, n=7) (Figure 7A). The same is true at 8 weeks post-injury (horizontal ladder, Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.32, p=.09, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.82, p=.01, n=7; peg walkway, Spearman rank correlation, 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.80, p=.02, n=7; narrow beam, Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.72, p=.0004, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs =0.90, p=.003, n=7). The single exception was the control group at 8 weeks post-injury on the peg walkway. In direct contrast, no relationships were identified for any of these skilled tasks between the amount of spared tissue and accurate targeting for the 4 week ch'abc treated group at the 4 and 8 weeks post-injury time points. Interestingly, by 16 weeks post-injury the relationship seen between the amount of spared tissue and accurate paw placement was no longer present on horizontal ladder or peg walkway for the control and 2 week ch'abc groups, though it was still present with regards to the narrow beam (Spearman rank correlation, control, rs=0.32, p=.06, n=19; 2 week ch'abc, rs=0.85, p=.01, n=7). At 16 weeks post-injury there were still no correlations between lesion size and performance in the 4 week ch'abc group. These results further support that ch'abc decreases the relationship between lesion size and locomotor recovery. The individual cat values of accurate ipsilateral hindlimb targeting at 4 weeks on the ladder in the control (Figure 7B), 2 week ch'abc (Figure 7C), and 4 week ch'abc (Figure 7D) treated groups also show a greater percentage of 4 week ch'abc treated animals (44%) fell into the low tissue sparing-high functional quadrant compared to control (11%) and 2 week ch'abc treated animals (0%).

Figure 7.

Accurate hindlimb paw placements and spared tissue correlations. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were determined which compared the lesion rank and percentage of accurate ipsilateral hindlimb paw placements on horizontal ladder, narrow beam, and peg walkway (A). Similar to recovery of task onset, both the control and 2 week ch'abc treated animals either significantly correlated, or trended towards a significant correlation with accurate placement on all three tasks at 4 and 8 weeks post injury. There are minimal correlations at 16 weeks post injury. In contrast, the 4 week ch'abc treated group has no significant correlations. As an example, the ranks and percentages of accurate targeting on horizontal ladder at 4 weeks post-injury for each individual animal are plotted for the control (B), 2 week ch'abc (C), and 4 week ch'abc (D) groups. Similar to Figure 4, black outlined boxes identify those cats which fall into the “larger lesion” category, while gray outlined boxes demarcate those individual cats that fall into the “higher functioning” category which is based on the average percentage of accurate ipsilateral hindlimb targeting for cats in the control group (25%). Therefore, all cats that accurately target more than an average of 25% are categorized as “higher functioning”. Data points inside the shaded gray boxes demarcate cats with larger lesions that also are remarkably “higher functioning”. The coefficient of determination (R2) and trend lines were determined for each of the groups. Significant correlations are indicated (*) along with trends (¥) in table. *, p<0.05; ¥, 0.05 < p < 0.10.

Discussion

Summary of Results

The current study reports that both 2 and 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment significantly increase the number of neurons in the axotomized RN with axons below the lesion. This effect has some specificity with regards to neuronal subpopulation as the same enhancement is not seen with CST neurons. Interestingly, despite similar RuST plasticity across the two ch'abc treatment groups, recovery of some movement features typically associated with the RuST and/or CST on the peg walkway was only seen following 4 weeks of treatment. This argues the importance of extending ch'abc treatment past 2 weeks for continued circuitry modification to support movement adaptations associated with distal limb targeting accuracy and control during the most demanding tasks. Although 2 weeks of ch'abc treatment was beneficial in that it accelerated recovery on the horizontal ladder and trended towards earlier recovery on the peg walkway, it may delay or disrupt other aspects of recovery that occur beyond two weeks. The variability in, and disruption off the temporal relationship with respect to, recovery of the ability to cross the narrow beam and peg walkways in the 2 week treated group suggest circuitry underlying performance is not the same as in controls. Comparison to performances of 4 week treated cats further suggests that supporting circuity continues to change and be responsive to ch'ase treatment beyond 2 weeks. Finally, using a large group of cats with diverse lesions, our findings additionally suggest that 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment effectively promotes motor function following larger, over-hemisected lesions such that aspects of recovery are comparable to those typically seen following smaller lesions.

Neuronal subpopulations are differentially affected by ch'abc

Rubrospinal Tract

In both 2 and 4 week treated animals, RuST axons grow beyond the lesion area in significant numbers relative to controls. The impact potential, based upon the percentage of neurons in the axotomized RN with axons below the lesion relative to the unlesioned side following ch'abc treatment (14-23%), is highlighted by previous work indicating as little as 5-10% sparing of the white matter at the lesion epicenter can support significant function (Blight, 1983). The RuST results suggest that both treatment durations set up a growth environment conducive for long descending axonal populations. Due to the differences in functional recovery seen with similar RN neuronal counts between 2 and 4 weeks of treatment, other tracts implicated in tasks requiring adaptive limb functions, like the vestibulospinal or propriospinal tracts (Alstermark et al., 1999; Drew et al., 2002; Lyalka et al., 2005), or locomotion and posture more generally (eg. Reticulospinal tract (Eidelberg et al., 1981; Brustein and Rossignol, 1998; Lyalka et al., 2005; Schepens et al., 2008)), may contribute to the recovery seen in the 4 week treated cats. Any of these long supraspinal pathways also may interact with intraspinal pathways to enhance control of hindlimb function (Alstermark et al., 1999; Drew et al., 2002). Equally likely is the possibility that RuST plasticity is incomplete following a shortened, relative to longer, treatment period.

Corticospinal Tract

The RuST and CST respond differently to injury and treatment. While RuST plasticity was significantly enhanced in both ch'abc treatment durations, similar changes were not seen in the CST, suggesting that all neuronal subpopulations are not similarly responsive to changes in the extracellular matrix mediated by 2 or 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment. This lack of CST plasticity is consistent with other reports, which indicate that the adult CST shows relatively little axonal growth following axotomy even in the presence of added growth factors (Schnell et al., 1994; Tuszynski et al., 1997; Blesch et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2001). However, some groups have reported enhanced CST plasticity in the rat with ch'abc (Bradbury et al., 2002; Barritt et al., 2006; García-Alías et al., 2009). Interspecies differences may contribute to the contrasting lack of CST responsiveness, including the differing locations of the CST in the spinal cord and the longer distance growth requirements in cats due to their larger spinal cords. This greater distance may have biased towards synapses with closer targets, including propriospinal interneurons above or at the lesion level (Bareyre et al., 2004), in our study. These types of responses, as well as increased terminal territories below the lesion due to sprouting of spared axons (Barritt et al., 2006; Starkey et al., 2012) would not be captured by counts of retrogradely labeled neurons used in the current study. However, the benefit of the neuronal counts used here is that they definitively distinguish if there is an increase in the number of neurons contributing to growth below the lesion.

Functional recovery suggests circuit differences

Horizontal Ladder

The current study used a range of tasks highlighting the different levels of recovery capable across controls and two ch'abc treatment duration groups. The ladder is commonly used and identified as a “skilled” locomotor task in rats (García-Alías et al., 2009; Mountney et al., 2013; Carmel et al., 2014) and cats (Amos et al., 1987; Marple-Horvat and Armstrong, 1999; Beloozerova et al., 2010; Stout and Beloozerova, 2013) due to the high level of motor cortex involvement (Beloozerova and Sirota, 1993; Marple-Horvat and Armstrong, 1999; Beloozerova et al., 2010). It, however, is the earliest of the three skilled tasks used in this study to show recovery and one on which even control animals regain proficiency over time. Thus, ladder performance is most likely supported by less complex circuitry than is required for the peg and narrow beam. The accelerated recovery in performance on the ladder seen in ch'abc treated groups occurred in <2 weeks which is within both the 2 and 4 week treatment periods. Interestingly, the supporting circuitry is not adequate for enhancing recovery of the other skilled tasks used.

Peg Walkway and Narrow Beam

Relative to other tasks, the peg walkway and narrow beam place profoundly greater restrictions on gait which include small support surfaces and a more fixed base of support. Thus, circuitry supporting these tasks is presumably more complex than circuitry supporting crossing of the ladder. This is supported by the longer recovery periods for both tasks following SCI even when ch'abc is introduced. As reported in our prior studies, 4 weeks of ch'abc treatment results in enhanced recovery of these more difficult skills (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011, Figure 4). Data from the control group shows a temporal relationship between recovery of ability to cross the peg walkway and narrow beam, in that recovery of one is typically followed by the other within 10 days (Figure 4). This timing suggests a relationship between the circuitry that is available to support these tasks. The disappearance of this relationship in cats treated for 2 weeks with ch'abc, suggests that treatment alters the spared connections and/or lesion-induced plasticity, and in some cats prevents or dramatically delays or prevents recovery of the ability to cross the peg runway or narrow beam (Figure 4). Interestingly, if the earliest onset from either task (peg or narrow beam) is used as the onset of the ‘most difficult’ tasks, the average onset for the 2 week ch'abc treated group (24 days) falls within the average onset for peg (~21 days) and narrow beam (~27 days) for the 4 week treated group which is much earlier than in the control groups. Together, these results suggest that 2 weeks of ch'abc treatment alters the circuitry present post-injury to more readily support the ladder task and begins to set the stage for recovery of more difficult tasks. The lack of or delayed recovery in 4 of the 2 week treated cats on one task or the other suggests that the circuitry changes are capable of effectively supporting one task but not both unless ch'abc is continued. Four weeks of ch'abc treatment supports continued circuitry development which readily supports the greater adaptability required to achieve both tasks within an average of 3 (peg) - 4 (narrow beam) weeks. Thus, the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd weeks post-injury may represent a critical point for chondroitinase's impact on aspects of skilled locomotor recovery. Combined, the results across the control and treated groups also suggest that the complete circuitry required for each task is somehow different.

The possibility that a short treatment period could be detrimental to some aspects of recovery, perhaps, should not be surprising. Prior studies have determined that the cessation of ch'abc delivery is accompanied by a reappearance of CS-GAGs (Hyatt et al., 2010) and perineuronal net formation that greatly limits both axonal and synaptic plasticity (Pizzorusso et al., 2002; Berardi et al., 2004). The premature halting of ch'abc delivery may lock unrefined, possibly abhorrent circuits, into place sending plasticity down the path to support select functions while blocking the connections necessary for others. However, elongating the period of CS-GAG degradation from 2 to 4 weeks seems to be sufficient for the formation of circuitry capable of supporting, and even enhancing, the demanding skill levels necessary for recovery on both the peg walkway and narrow beam tasks with regards to limb adaptation required for paw effective placement.

Benefits of ch'abc across a range of lesion magnitudes/sizes

The positive relationship seen between spared tissue and functional recovery in the control group is consistent with the literature (Molt et al., 1979; Norrie et al., 2005; Byrnes et al., 2010; Semler et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2013). Intriguingly, the current study shows that this relationship is lost in cats treated for 4, but not 2, weeks of ch'abc. Although recent work in which a single ch'abc dose was given at 3 weeks post-dorsal column transection suggests that the linear relationship between recovery and lesion size may shift (Zhao et al., 2013), the current findings are the first to suggest a disruption of the linear relationship following ch'abc treatment. Specifically, cats with substantially less spared tissue ultimately achieved recovery levels similar to cats with more sparing, suggesting that 4 weeks of treatment lessened the importance of tissue sparing within the range of lesions evaluated. This is presumably a result of extensive plasticity. These findings emphasize the robust therapeutic effects of ch'abc, in that the difficult tasks can be supported following an injury with less tissue sparing if treated for a sufficient period of time with ch'abc.

Conclusion

The current study concludes that the RuST is more responsive to ch'abc than the CST, but that the increased number of RN neurons with axons below the lesion alone does not necessarily confer increased behavioral recovery. This highlights the obvious importance of supporting the formation of connections which mediate improved motor performance in addition to promoting axonal growth. We found that the appropriate period of ch'abc delivery may be biased by the motor recovery assessed. By assessing a range of motor abilities, it is apparent that ch'abc for too short of a period may be detrimental with respect to some aspects of functional recovery. The negative effect with respect to attainment of highly adaptive behaviors seen with 2 weeks of treatment did not occur in cats treated for a longer, 4 week period (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011). However, it is unknown if treatment beyond 4 weeks may show even greater benefits. Further, through the comparison of functional recovery across a range of lesion sizes, we found that 4 weeks of ch'abc not only enhances the functional recovery of several high-end skilled features, but, can do so in cats with larger lesions. Together, the current study and our prior publications (Tester and Howland, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2011) demonstrate that ch'abc treatment can lead to robust enhancement of functional recovery after spinal hemisection in the cat and diminish the impact of lesion size, however, the effect extent appears closely linked to the timing and/or duration of treatment. Understanding the impact of ch'abc across different time frames or at various time points is important as it is emerging as a treatment of choice in combination therapies (García-Alías et al., 2011; Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2012; Tom et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Francis et al., 2014;Zhao et al., 2013).

Highlights.

Chondroitinase-enhanced rubrospinal growth exceeds that of the corticospinal tract

Extended chondroitinase treatment is required for control of limb accuracy

Insufficient chondroitinase treatment may be less effective than no treatment

Challenging tasks differentiate recovery mediated by changes in treatment duration

4 weeks of chondroitinase treatment is effective across a range of SCI magnitudes

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by DVA RR&D Merit B7165-R and Center Grant B6793C, NIH NS050699, 8-P30GM103507, The Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust, Rebecca F. Hammond Endowment, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Scholars Program in Integrative Biophysics, and the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation. We extend many thanks to Darlene A. Burke for assisting with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

In the Jefferson et al. (2011) publication, neuronal counts for the axotomized RN were unintentionally reported from every 100 micons and the control side every 200. However, the percentage values that were reported are correct and thus the interpretations are still accurate. This current comparison reports and uses neuronal counts from every 200 microns through both the right and left RN for 2 and 4 week treated animals

Disclaimer – The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the DVA or the US government.

List of References

- Alstermark B, Isa T, Ohki Y, Saito Y. Disynaptic pyramidal excitation in forelimb motoneurons mediated via C(3)-C(4) propriospinal neurons in the Macaca fuscata. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3580–3585. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos A, Armstrong DM, Marple-Horvat DE. A ladder paradigm for studying skilled and adaptive locomotion in the cat. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;20:323–340. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, Schwab ME. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barritt AW, Davies M, Marchand F, Hartley R, Grist J, Yip P, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ. Chondroitinase ABC promotes sprouting of intact and injured spinal systems after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2006;26:10856–10867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloozerova IN, Farrell BJ, Sirota MG, Prilutsky BI. Differences in movement mechanics, electromyographic, and motor cortex activity between accurate and nonaccurate stepping. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:2285–2300. doi: 10.1152/jn.00360.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloozerova IN, Sirota MG. The role of the motor cortex in the control of accuracy of locomotor movements in the cat. J Physiol. 1993;461:1–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Pizzorusso T, Maffei L. Extracellular matrix and visual cortical plasticity: freeing the synapse. Neuron. 2004;44:905–908. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A, Uy HS, Grill RJ, Cheng JG, Patterson PH, Tuszynski MH. Leukemia inhibitory factor augments neurotrophin expression and corticospinal axon growth after adult CNS injury. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1999;19:3556–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03556.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustein E, Rossignol S. Recovery of locomotion after ventral and ventrolateral spinal lesions in the cat. I. Deficits and adaptive mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1245–1267. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight AR. Cellular morphology of chronic spinal cord injury in the cat: analysis of myelinated axons by line-sampling. Neuroscience. 1983;10:521–543. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Carter LM. Manipulating the glial scar: chondroitinase ABC as a therapy for spinal cord injury. Brain Res Bull. 2011;84:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LDF, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Silver J. The role of extracellular matrix in CNS regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes KR, Fricke ST, Faden AI. Neuropathological differences between rats and mice after spinal cord injury. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2010;32:836–846. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WBJ, Bradbury EJ, Lidierth M, Jones M, Duffy PJ, Pezet S, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC-mediated plasticity of spinal sensory function. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2008;28:11998–12009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3877-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Kimura H, Martin JH. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex in the uninjured hemisphere after chronic unilateral injury promotes recovery of skilled locomotion through ipsilateral control. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2014;34:462–466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creeley CE, Dikranian KT, Dissen GA, Back SA, Olney JW, Brambrink AM. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the fetal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:626–638. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Jiang W, Widajewicz W. Contributions of the motor cortex to the control of the hindlimbs during locomotion in the cat. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:178–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelberg E, Story JL, Walden JG, Meyer BL. Anatomical correlates of return of locomotor function after partial spinal cord lesions in cats. Exp Brain Res. 1981;42:81–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00235732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelberg E, Nguyen LH, Deza LD. Recovery of locomotor function after hemisection of the spinal cord in cats. Brain Res Bull. 1986;16:507–515. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis NL, Hunger PM, Donius AE, Wegst UGK, Wheatley MA. Strategies for neurotrophin-3 and chondroitinase ABC release from freeze-cast chitosan–alginate nerve-guidance scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/term.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtrey CM, Fawcett JW. The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G, Barkhuysen S, Buckle M, Fawcett JW. Chondroitinase ABC treatment opens a window of opportunity for task-specific rehabilitation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/nn.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G, Petrosyan HA, Schnell L, Horner PJ, Bowers WJ, Mendell LM, Fawcett JW, Arvanian VL. Chondroitinase ABC combined with neurotrophin NT-3 secretion and NR2D expression promotes axonal plasticity and functional recovery in rats with lateral hemisection of the spinal cord. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:17788–17799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4308-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimpe B, Silver J. A novel DNA enzyme reduces glycosaminoglycan chains in the glial scar and allows microtransplanted dorsal root ganglia axons to regenerate beyond lesions in the spinal cord. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2004;24:1393–1397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4986-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays W. Statistics. 3rd ed. Holt; Rinehart; Winston; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Helgren ME, Goldberger ME. The recovery of postural reflexes and locomotion following low thoracic hemisection in adult cats involves compensation by undamaged primary afferent pathways. Exp Neurol. 1993;123:17–34. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JD, Tom VJ, Mayes D, Wagoner G, Phillips N, Silver J. Combining an autologous peripheral nervous system “bridge” and matrix modification by chondroitinase allows robust, functional regeneration beyond a hemisection lesion of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2006;26:7405–7415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1166-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland DR, Bregman BS, Tessler A, Goldberger ME. Development of locomotor behavior in the spinal kitten. Exp Neurol. 1995a;135:108–122. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland DR, Bregman BS, Tessler A, Goldberger ME. Transplants enhance locomotion in neonatal kittens whose spinal cords are transected: a behavioral and anatomical study. Exp Neurol. 1995b;135:123–145. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt AJT, Wang D, Kwok JC, Fawcett JW, Martin KR. Controlled release of chondroitinase ABC from fibrin gel reduces the level of inhibitory glycosaminoglycan chains in lesioned spinal cord. J Control Release Off J Control Release Soc. 2010;147:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson SC, Tester NJ, Howland DR. Chondroitinase ABC promotes recovery of adaptive limb movements and enhances axonal growth caudal to a spinal hemisection. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:5710–5720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4459-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LL, Margolis RU, Tuszynski MH. The chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans neurocan, brevican, phosphacan, and versican are differentially regulated following spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2003a;182:399–411. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LL, Sajed D, Tuszynski MH. Axonal regeneration through regions of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan deposition after spinal cord injury: a balance of permissiveness and inhibition. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2003b;23:9276–9288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LL, Yamaguchi Y, Stallcup WB, Tuszynski MH. NG2 is a major chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan produced after spinal cord injury and is expressed by macrophages and oligodendrocyte progenitors. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2002;22:2792–2803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02792.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Schut D, Wang J, Fehlings MG. Chondroitinase and growth factors enhance activation and oligodendrocyte differentiation of endogenous neural precursor cells after spinal cord injury. PloS One. 2012;7:e37589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhtz-Buschbeck JP, Boczek-Funcke A, Mautes A, Nacimiento W, Weinhardt C. Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord hemisection: an X-ray study of the cat hindlimb. Exp Neurol. 1996;137:212–224. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie S, Drew T. Discharge characteristics of neurons in the red nucleus during voluntary gait modifications: a comparison with the motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1791–1814. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons ML, Howland DR, Anderson DK. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan immunoreactivity increases following spinal cord injury and transplantation. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:51–65. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Neurotrophism without neurotropism: BDNF promotes survival but not growth of lesioned corticospinal neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:456–470. doi: 10.1002/cne.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyalka VF, Zelenin PV, Karayannidou A, Orlovsky GN, Grillner S, Deliagina TG. Impairment and recovery of postural control in rabbits with spinal cord lesions. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3677–3690. doi: 10.1152/jn.00538.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marple-Horvat DE, Armstrong DM. Central regulation of motor cortex neuronal responses to forelimb nerve inputs during precision walking in the cat. J Physiol 519 Pt. 1999;1:279–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0279o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molt JT, Nelson LR, Poulos DA, Bourke RS. Analysis and measurement of some sources of variability in experimental spinal cord trauma. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:784–791. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.6.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern DA, Asher RA, Fawcett JW. Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans in the CNS injury response. Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:313–332. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Tosolini AP, Goldstein JD, Whishaw IQ. Impaired arpeggio movement in skilled reaching by rubrospinal tract lesions in the rat: a behavioral/anatomical fractionation. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:2439–2451. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountney A, Zahner MR, Sturgill ER, Riley CJ, Aston JW, Oudega M, Schramm LP, Hurtado A, Schnaar RL. Sialidase, chondroitinase ABC, and combination therapy after spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:181–190. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrie BA, Nevett-Duchcherer JM, Gorassini MA. Reduced functional recovery by delaying motor training after spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:255–264. doi: 10.1152/jn.00970.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson L-G, Alstermark B, Blagovechtchenski E, Isa T, Sasaski S. Skilled digit movements in feline and primate--recovery after selective spinal cord lesions. Acta Physiol Oxf Engl. 2007;189:141–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett JW, Maffei L. Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science. 2002;298:1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1072699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepens B, Stapley P, Drew T. Neurons in the pontomedullary reticular formation signal posture and movement both as an integrated behavior and independently. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2235–2253. doi: 10.1152/jn.01381.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell L, Schneider R, Kolbeck R, Barde YA, Schwab ME. Neurotrophin-3 enhances sprouting of corticospinal tract during development and after adult spinal cord lesion. Nature. 1994;367:170–173. doi: 10.1038/367170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semler J, Wellmann K, Wirth F, Stein G, Angelova S, Ashrafi M, Schempf G, Ankerne J, Ozsoy O, Ozsoy U, Schönau E, Angelov DN, Irintchev A. Objective measures of motor dysfunction after compression spinal cord injury in adult rats: correlations with locomotor rating scores. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:1247–1258. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Thomas LC, Fok-Seang J, Stevens J, Du JS, Muir E, Faissner A, Geller HM, Rogers JH, Fawcett JW. An inhibitor of neurite outgrowth produced by astrocytes. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 6):1687–1695. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow DM, Lemmon V, Carrino DA, Caplan AI, Silver J. Sulfated proteoglycans in astroglial barriers inhibit neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exp Neurol. 1990;109:111–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(05)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, Matzelle DD, Ray SK, Banik NL. Estrogen as a neuroprotective agent in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07521.x. discussion 159–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, Matzelle DD, Wilford GG, Ray SK, Banik NL. Estrogen attenuated markers of inflammation and decreased lesion volume in acute spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:283–293. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey ML, Bartus K, Barritt AW, Bradbury EJ. Chondroitinase ABC promotes compensatory sprouting of the intact corticospinal tract and recovery of forelimb function following unilateral pyramidotomy in adult mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:3665–3678. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout EE, Beloozerova IN. Differential responses of fast- and slow-conducting pyramidal tract neurons to changes in accuracy demands during locomotion. J Physiol. 2013;591:2647–2666. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester NJ, Howland DR. Chondroitinase ABC improves basic and skilled locomotion in spinal cord injured cats. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]