ABSTRACT

Mesothelin (MSLN) is a cell surface glycoprotein overexpressed in several solid malignancies, including gastric, lung, mesothelioma, pancreatic and ovarian cancers. While several MSLN-targeting therapeutic approaches are in development, only limited efficacy has been achieved in patients. A potential shortcoming of several described antibody-based approaches is that they target the membrane distal region of MSLN and, additionally, are known to be handicapped by the high levels of circulating soluble MSLN in patients. We show here, using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting different MSLN-spanning epitopes, that the membrane-proximal region resulted in more efficient killing of MSLN-positive tumor cells in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) assays. Surprisingly, no augmented killing was observed in antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) by mAbs targeting this membrane-proximal region. To further increase the ADCP potential, we, therefore, generated bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) coupling a high-affinity MSLN binding arm to a blocking CD47 arm. Here, targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN demonstrated enhanced ADCP activity compared to membrane-distal domains when the bsAbs were used in in vitro phagocytosis killing assays. Importantly, the superior anti-tumor activity was also translated in xenograft tumor models. Furthermore, we show that the bsAb approach targeting the membrane-proximal epitope of MSLN optimized ADCC activity by augmenting FcγR-IIIA activation and enhanced ADCP via a more efficient blockade of the CD47/SIRPα axis.

KEYWORDS: Mesothelin, CD47, bispecific antibodies, membrane proximity, ADCC, ADCP, solid tumors

Introduction

Immunotherapy using antibodies (Abs) is now becoming indispensable for the treatment of many solid and difficult-to-treat cancers.1−4 Abs can elicit a number of effector mechanisms to deplete tumor cells, including Ab-dependent cell-meditated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP). In the past two decades, bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) engaging two different antigens or two epitopes on the same antigen have emerged as a new class of therapeutic molecules.5-8 Engaging two antigens by bsAbs enables unique modes of action, such as retargeting immune cells to cancer cells, improving effector-cell functions such as phagocytosis or altering target mobility at the cell surface.8-10

Interestingly, it has emerged that Abs binding to different regions or epitopes on a target can elicit diverse effector functions. Various explanations for this observation have been proposed, including antigen size, location of the epitope and the inherent properties of the target molecule (e.g., membrane mobility).11-14 The impact of epitope location on effector functions engaged by Abs has recently been highlighted using CD20 and CD307 as targets in B cell malignancies, demonstrating increased ADCC activity with Abs targeting epitopes closer to the cell surface.11,15 Although it is accepted that different Abs binding to the same target can elicit different therapeutic efficacy, the underlying mechanisms were scarcely elucidated. A better understanding of these mechanisms will facilitate the development of more efficacious therapeutic Abs.

Mesothelin (MSLN) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein encoded as a 628-amino acids precursor addressed to the cell membrane and cleaved by furin into a membrane-attached 40 kD mature form (i.e., MSLN), releasing the soluble megakaryocyte potentiating factor. Due to limited efficacy in patients, novel MSLN-targeting modalities have been introduced to enhance tumor-killing potential (e.g., antibody-drug conjugates, recombinant immunotoxins and CAR-T cells).16-20

Here, we employed a bsAb approach that pairs a high-affinity anti-MSLN targeting arm to an anti-CD47 arm with an optimized affinity that drives the selective CD47 blockade to MSLN-positive cells.8 CD47 is an innate immune checkpoint that allows tumor cells to escape immune surveillance through its interaction with the signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) on phagocytes. Blockade of CD47 enhances the elimination of CD47-positive tumor cells across multiple preclinical models and has demonstrated efficacy in early phase clinical trials.21-27 To this end, a panel of anti-MSLN monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and CD47xMSLN bsAbs carrying the same anti-CD47 arm and different anti-MSLN arms were generated and characterized. The anti-MSLN mAb targeting a membrane-proximal region was more efficient at inducing ADCC as compared to mAbs targeting more membrane-distal MSLN regions. This increased killing potential was not seen in ADCP assays. Interestingly, targeting a membrane-proximal MSLN epitope with the CD47xMSLN bsAb increased both ADCC and ADCP tumoricidal activities. These observations were translated in vivo using a mouse xenograft tumor model. Taken together, the study herein demonstrates that targeting a membrane-proximal epitope on MSLN elicits optimal effector functions, which may have implications for the development of future Ab-based targeting approaches.

Results

Generation of anti-MSLN Abs targeting extracellular MSLN epitopes

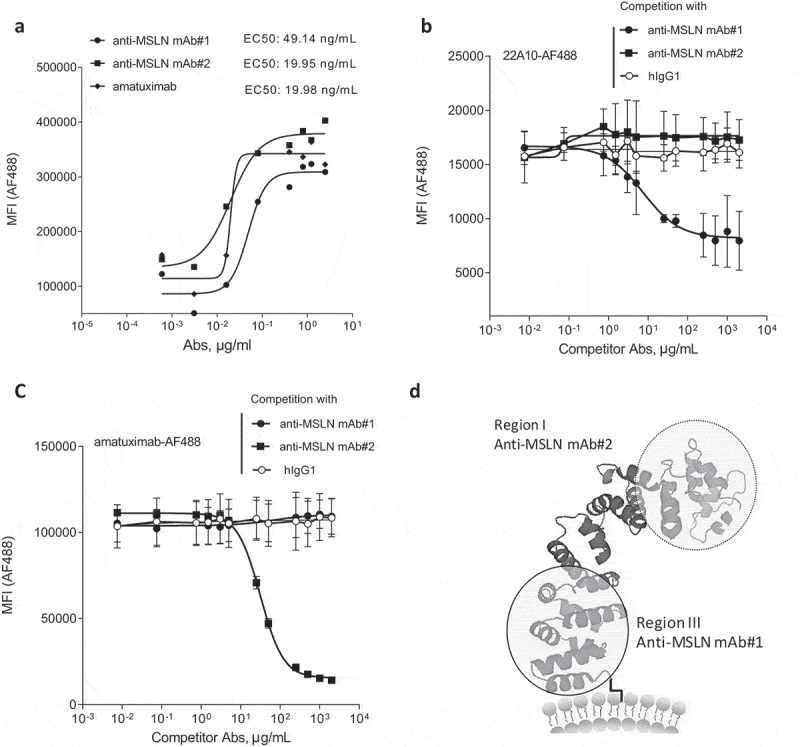

Two anti-MSLN human IgG1 mAbs generated using phage display technology were analyzed in this study (i.e., anti-MSLN mAb#1 and mAb#2). The fluorescence-activated cell sorting binding profiles on the human MSLN-positive gastric epithelial cancer cell line NCI-N87 demonstrated a more potent binding profile for mAb#2 compared to mAb#1 (EC50 values of 19.95 vs 49.14 ng/mL, respectively). Additionally, we found that mAb#2 shared a similar binding potency with the benchmark anti-MSLN mAb amatuximab (EC50 values of 19.95 vs 19.98 ng/mL, respectively, Figure 1a). We then investigated the epitope-binding regions for mAb#1 and mAb#2. Mature membrane-expressed MSLN has three distinct domains: region-I (residues 296–390), region-II (residues 391–486) and region-III (residue 487–581).28 Competitive binding studies were performed with the 22A10 mAb, an anti-MSLN Ab described to bind an epitope within the membrane-proximal region-III.29 We show that mAb#1 interfered with mAb 22A10’s binding to MSLN-positive cells (Figure 1b), while mAb#2 interfered with the binding of amatuximab (Figure 1c), which has been shown to recognize an epitope in the membrane-distal region-I of MSLN.30 Finally, in contrast to 22A10, mAb#2 did not interfere with mAb#1 binding to MSLN-positive cells, further demonstrating that mAb#1 and mAb#2 do not bind overlapping epitopes (Suppl Figure 1). Based on these binding specificities (represented in the Figure 1d schematic), our next aim was to determine whether the binding to different epitope locations affects mAb-mediated effector functions.

Figure 1.

Generation of anti-MSLN antibodies targeting either membrane-proximal or distal regions within MSLN. (a) Comparative binding curves of anti-MSLN mAb#1, mAb#2, and amatuximab. NCI-N87 cancer cells were incubated with a serial dilution of AF488-labeled mAbs for 30 min at 4°C before the AF488 signal was analyzed on a flow cytometer as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per condition. EC50 values (in ng/mL) were calculated by the Prism 5 software. A representative graph of three independent experiments is shown. (b-c) Competitive binding assay of anti-MSLN mAbs using a cell-based fluorescent assay format. AF488-labeled 22A10 mAb (b) or amatuximab (c) tested at 10 μg/mL antibody was incubated with either a serially dilution (7.5 ng/mL – 2 mg/mL) of anti-MSLN mAb#1, mAb#2 or an irrelevant hIgG1 isotype control used as competitor antibodies. The mixtures were incubated with NCI-N87 cells for 10 min at 4°C. AF488 staining was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean values ± SEM of a minimum of two independent experiments. (d) A protein structure model of human MSLN depicting the binding domains of mAb#1 and mAb#2.

Targeting the MSLN membrane-proximal region affords more efficient ADCC

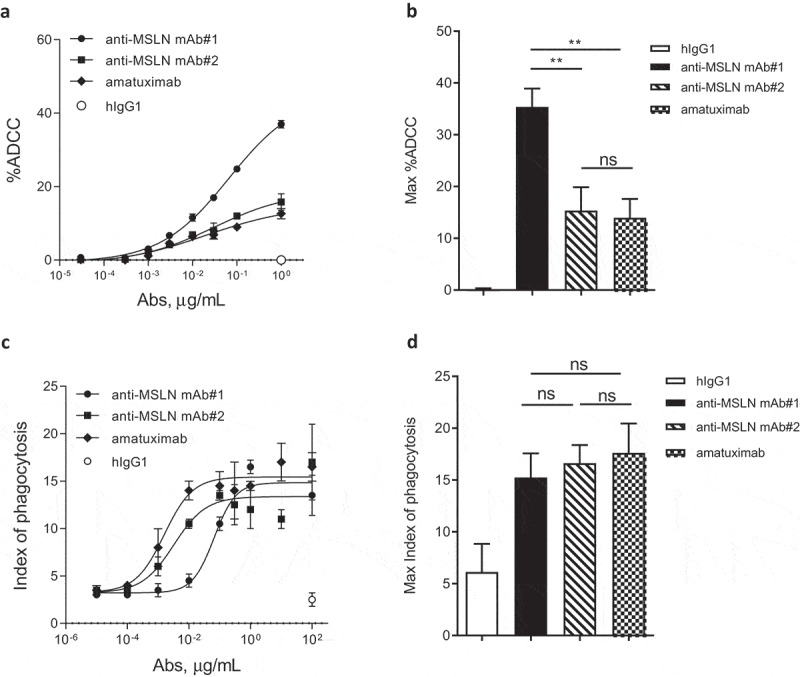

To assess the impact of the mAb-binding domains to potentiate tumoricidal activities, ADCC was evaluated with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as a source of effector cells. Using NCI-N87 cells as target cells, the anti-MSLN mAb#1 was more effective at inducing ADCC compared to mAbs targeting membrane-distal epitopes (mAb#2 and amatuximab, respectively) (Figure 2a,b). The MSLN membrane proximal control antibody (e.g., 22A10) showed a similar increased ADCC activity using the FcγR-IIIA Jurkat reporter surrogate assay (Suppl Figure 2). We next wanted to extend this work to evaluate the impact in ADCP of NCI-N87 cells using monocyte-derived macrophages as effector cells. Targeting a membrane-proximal region did not result in increased phagocytosis. Indeed, mAb#2 and amatuximab were more potent at inducing phagocytosis of cancer cells compared to mAb#1 (EC50 of 3.2 ng/mL, 1.6 ng/mL and 65.8 ng/mL for mAb#2, amatuximab and mAb#1, respectively; Figure 2c), whereas the overall maximal killing by phagocytosis was similar across anti-MSLN mAbs (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

The anti-MSLN Ab targeting a membrane-proximal region showed more efficient killing through ADCC but not by ADCP as compared to Abs targeting more membrane-distal region. (a) %ADCC mediated by a fixed dose of hIgG1 isotype control (e.g., 1 μg/mL) or a dose range (0.03 ng/mL – 1 μg/mL) of anti-MSLN mAb#1, mAb#2, or amatuximab using NCI-N87 cells as targets. The graph depicts an example of a dose–response curve tested in duplicate. (b) The graph summarizes the mean of the %ADCC ± SEM mediated by anti-MSLN mAbs or hIgG1 isotype control (all tested at 1 μg/mL) of 3 independent experiments using different donors as a source of effector cells. (c) ADCP of NCI-N87 target cells with a fixed concentration of hIgG1 isotype control (e.g., 100 μg/mL) or a dose–response of anti-MSLN mAb#1, mAb#2, or amatuximab (0.01 ng/mL – 100 μg/mL). The graph depicts a representative ADCP curve obtained and tested in triplicate. Data are presented as an index of phagocytosis defined as the number of target cells engulfed per 100 macrophages. (d) The graph depicts the maximum index of phagocytosis (e.g., obtained at 10 μg/mL) ± SEM mediated by anti-MSLN mAbs or hIgG1 isotype control (all tested at 10 μg/mL) of 4 independent experiments using different donors as a source of macrophages. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired T-test: **p < .01, ns = not significant.

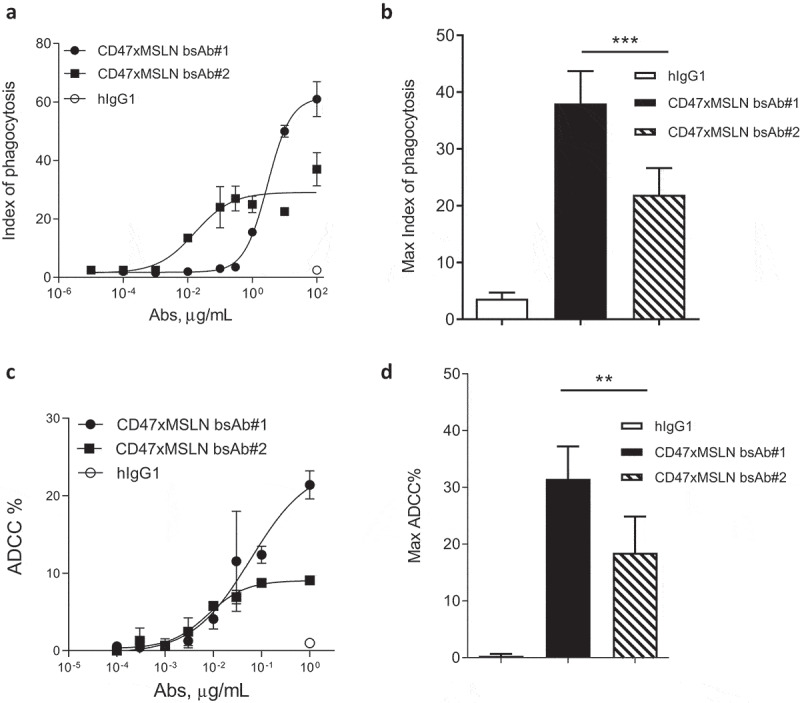

A bispecific approach co-engaging CD47 and MSLN at a membrane-proximal region affords potent ADCC and ADCP of cancer cells

Macrophage-mediated phagocytosis is a clinically relevant effector mechanism of anti-cancer therapeutic antibodies that can be enhanced upon blockade of the CD47 “don’t eat me” signal.31-34 We have previously demonstrated that a bispecific approach co-engaging CD47 and a tumor-associated antigen (TAA) afforded an increased ADCP and ADCC over the anti-TAA mAbs alone.8,9 Here, we tested the ability of the bsAb approach, using various MSLN epitopes as a target for one bsAb arm coupled to the blockade of CD47, to increase the phagocytosis potential. As such, CD47xMSLN bsAbs were generated coupled either to the anti-MSLN-binding arm of mAb#1 (designated as bsAb#1) or of mAb#2 (designated as bsAb#2). Although mAb#1 started to induce detectable phagocytosis at lower concentration than bsAb#1, bsAb#1 induced a much greater level of phagocytosis compared to mAb#1 at maximum concentration (Suppl Figure 3A). Similar results were generated by comparing the bsAb#2 with the anti-MSLN-mAb#2 (Suppl Figure 3B). We then compared ADCP in the presence of increasing concentrations of either bsAb#1 or bsAb#2. Interestingly, even while bsAb#2 was able to initiate phagocytosis at a lower concentration compared to bsAb#1 (phagocytosis observed at 0.01 μg/mL for bsAb#2, whereas no phagocytosis was observed with bsAb#1 at the same concentration), the maximal phagocytosis index obtained with bsAb#1 was higher than that obtained with bsAb#2, 61 vs 27, respectively (Figure 3a). These data were confirmed using seven different donors as a source of whole blood to derive macrophages (Figure 3b). Next, we assessed whether bsAb#1 also allowed superior ADCC activity. The bsAb#1 induced higher levels of ADCC in a dose–response killing assay compared to the bsAb#2 (Figure 3c). The results were further confirmed by three independent experiments demonstrating significantly higher levels of ADCC mediated by bsAb#1 at maximal concentration than that mediated by bsAb#2 (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

CD47-targeting bsAb engaging a MSLN-membrane proximal region increases the elimination of tumor cells by both ADCC and phagocytosis. Anti-MSLN mAbs generated were converted into a CD47-targeting bsAb format sharing the same CD47 arm (e.g., similar affinity). Anti-CD47xMSLN bsAbs were compared in phagocytosis (a, b) or ADCC (c, d) assays. NCI-N87 cells were incubated with donor-derived macrophages (A, B) or PBMC (C, D) and increasing concentrations of either the CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or the bsAb#2. The hIgG1 was tested at the maximum concentration (e.g., 100 or 1 μg/mL for phagocytosis and ADCC, respectively). A representative ADCP (a) and ADCC (c) dose–response curve is shown. (b, d) Graphs summarizing maximum killing induced either by the CD47xMSLN bsAb#1, bsAb#2, or the hIgG isotype control, all tested at 100 or 1 μg/mL for phagocytosis (b) and ADCC, respectively (d). Graphs are combining maximum mean killing values by ADCP and ADCC ± SEM of 7 and 3 independent experiments, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired T-test: **p < .01, ***p < .001.

We also compared the bsAbs with another tumor cell line, the lung carcinoma NCI-H226, characterized by a higher expression level of both targets, MSLN, and CD47 (Suppl Figure 4a). Data confirmed that bsAb#1 induced higher levels of tumoricidal activity at a maximum concentration by both ADCC and ADCP compared to bsAb#2 (Suppl Figures 4B-C). As observed with the corresponding anti-MSLN mAbs, the superior functional activity at maximum concentration is not correlated to the binding potency of the Abs, as bsAb#2 demonstrated a higher potency at binding MSLN-positive cancer cells compared to the CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 (Suppl Figure 5). These data highlight that in a CD47 bispecific approach, engaging a MSLN membrane-proximal domain is key for inducing robust ADCC and ADCP of MSLN-positive cancer cell lines.

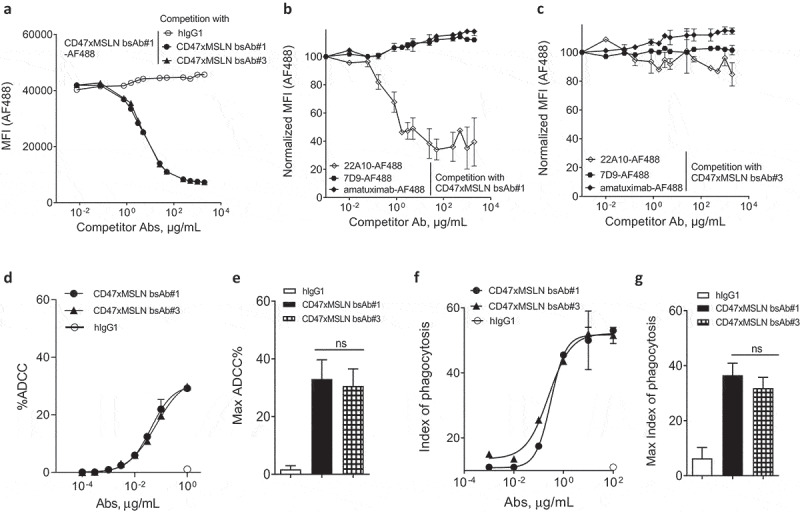

Targeting different epitopes within the membrane-proximal MSLN region affords similar tumoricidal activity

To confirm that the benefit in tumoricidal activities observed in vitro is related to the epitope location rather than the inherent properties of a bsAb, we compared bsAb#1 to another CD47-targeting bsAb, bsAb#3, also targeting an epitope in the membrane-proximal region. A binding competition assay showed that bsAb#1 and bsAb#3 competed with each other for binding to MSLN-positive cancer cells suggesting overlapping membrane-proximal epitopes (Figure 4a). Furthermore, the competition curve of bsAb#3 vs labeled bsAb#1 was almost identical to that of bsAb#1 vs labeled bsAb#1, suggesting the two bsAbs bound to MSLN-positive cells with similar affinities. Interestingly, the anti-MSLN mAb 22A10 only competed with bsAb#1 (Figure 4b) but not with bsAb#3 (Figure 4c), suggesting that the MSLN epitopes of the bsAbs #1 and #3 are not identical. As controls, neither of the two bsAbs competed with the anti-MSLN mAb 7D9, a mAb targeting a non-linear epitope identified in the intermediate region-II (aa 447–450 and aa 467–470), nor with amatuximab targeting the region-I of MSLN (Figure 4b,c).29,30 Further mapping of the epitopes for anti-MSLN mAb#1 and mAb#3 confirmed that, within region-III of MSLN, both anti-MSLN mAbs recognize different amino acid (aa) residues. mAb#1 recognizes two distinct membrane-proximal epitopes, one in the region aa 504–535 and the other in region aa 546–573, and mAb#3 is mainly specific for the region aa 546–573 (Suppl Figures 6A-B), suggesting that mAb#3 binds to a more membrane-proximal region on MSLN than mAb#1. The respective CD47-targeting bsAb variants (bsAbs 1# and #3) were then tested in ADCC and ADCP assays. When NCI-N87 target cells were incubated with increasing bsAb concentrations, the two bsAbs showed equivalent ADCC activities (Figure 4d,e). Similar data were generated by comparing the two bsAbs in phagocytosis assays (figure 4f,g). Overall, these results suggest that engaging different membrane-proximal epitopes of MSLN with CD47-blocking bsAbs affords similar in vitro cancer cell killing activity.

Figure 4.

Targeting different membrane-proximal epitopes within MSLN affords CD47-targeting bsAbs similar tumoricidal activity. Binding domain characterization of CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 and bsAb#3 (a–c) using a cell-based fluorescence assay format and NCI-N87 cells as a target. AF488-labeled CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 tested at 10 μg/mL was incubated with a dose–response (7.5 ng/mL – 2 mg/mL) of naked CD47xMSLN bsAb#1, bsAb#3, or an irrelevant isotype control used as competitor antibodies (a). AF488-labeled anti-MSLN mAbs (22A10, 7D9, or amatuximab) tested at 10 μg/mL were incubated with a dose–response of naked CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 (b) or bsAb#3 (c) used as competitors. The mixtures were incubated on NCI-N87 cells for 10 min at 4°C. Resulting fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean values ± SEM of a minimum of two independent experiments. Comparative in vitro tumoricidal activities by ADCC (d, e) and ADCP (f, g). A representative dose-–response is shown for ADCC (d) and ADCP (f). Maximum killing ADCC (e) and ADCP (g) efficacy mediated by CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 and bsAb#3 are presented, all tested at 1 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL, respectively. Data are means ± SEM of a minimum of five independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired T-test: ns = not significant.

Engaging the membrane-proximal region within MSLN increases FcγR-IIIA signaling

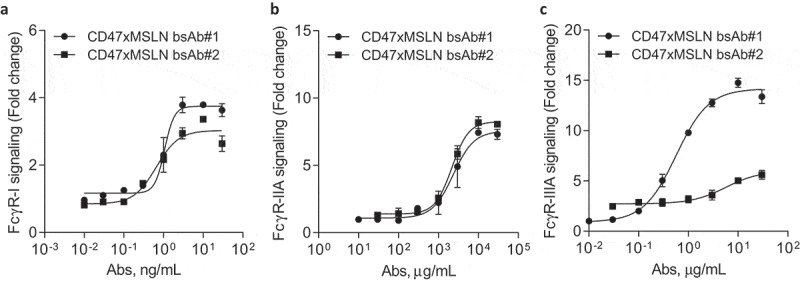

Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated ADCC and macrophage-mediated ADCP are two major mechanisms triggered by the interaction of the antibody crystallizable fragment (Fc) domain with Fcγ receptors (FcγRs). In contrast to NK cells expressing only FcγR-IIIA, macrophages express all classes of activating FcγRs (FcγR-I, -IIA and -IIIA).35 In order to decipher the contribution of FcγRs observed in the in vitro killing activities mediated by bsAb#1 and bsAb#2, we investigated whether targeting a MSLN membrane-proximal or -distal domain would affect specific signaling of FcγRs. Binding assays demonstrated that bsAb#1 and bsAb#2, both on a hIgG1-Fc backbone, have similar binding profiles to recombinant human FcγR-IIA and IIIA (Suppl Figures 7A-B). We then compared bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 opsonized NCI-N87 cancer cells in their capacity to activate specific FcγR-luciferase-reporter Jurkat cells. We found that the activity of FcγR-I and -IIA in the reporter Jurkat cells co-cultured with target cancer cells, was similarly increased by bsAb#1 and bsAb#2 (Figure 5a,b). Interestingly, the FcγR-IIIA reporter cells were activated by bsAb#1 with around 13.4-fold increase in maximal luciferase activity, while the bsAb#2 induced a twofold increase in maximal luciferase activity (Figure 5c). Similar data were generated by comparing the membrane distal and proximal anti-MSLN antibodies (e.g., amatuximab and mAb#2 versus 22A10 and mAb#1, respectively) (Suppl Figure 2). These data suggest that targeting a MSLN membrane-proximal region with a mAb or in a CD47-bsAb format favors FcγR-IIIA signaling.

Figure 5.

Engaging a membrane-proximal region within MSLN increases FcγR-IIIA signaling. NCI-N87 target cells were incubated with a dose range of either CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 (a–c), then mixed with engineered FcγR-I (a), FcγR-IIA (H131 polymorphism) (b) or FcγR-IIIA (V158 polymorphism) (c) reporter Jurkat cell lines. After 6 h of co-culture at 37°C, the luciferase activity was measured. Data are then presented as fold change induction. Graphs depict a representative dose–response curve obtained for a minimum of two independent experiments tested in duplicate.

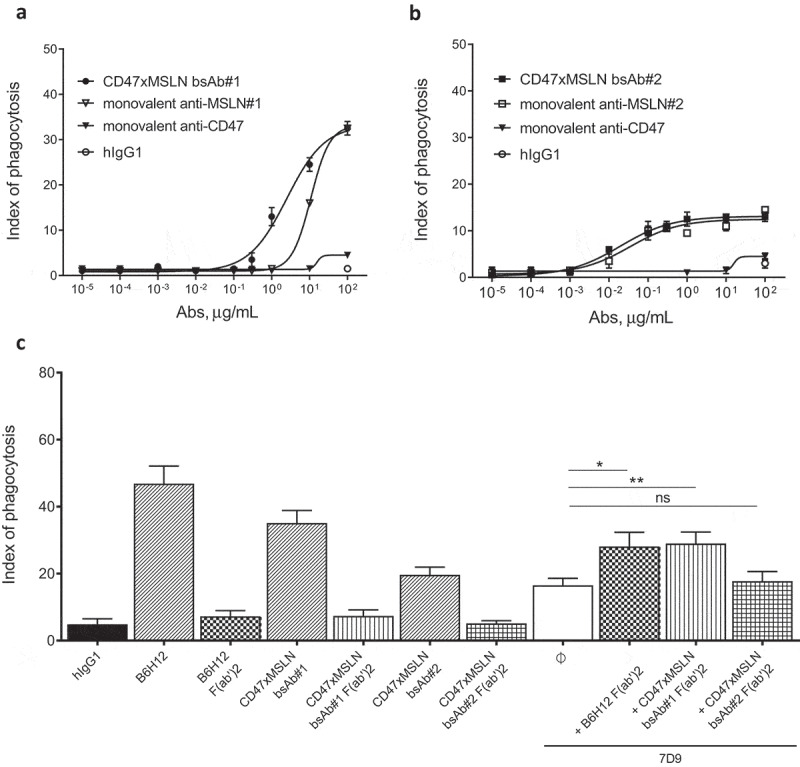

Co-engaging CD47 and a MSLN membrane-proximal domain results in enhanced phagocytosis of cancer cells by efficiently disrupting the CD47/SIRPα “don’t eat me signal”

The CD47 arm used to generate the CD47xMSLN bsAbs presented herein is fixed and characterized by an affinity to human CD47 of 500 nM.9 Therefore, the CD47 arm of all CD47xMSLN bsAb will bind to CD47 with a similar affinity. We hypothesize that the more efficient ADCP observed with bsAb#1, as compared to the bsAb#2, is due to better CD47/MSLN co-engagement leading to a more efficient disruption of the CD47/SIRPα axis. To this end, bsAb#1 and #2 were tested in ADCP assays and compared to monovalent anti-CD47 or -MSLN control antibodies (where one of the antigen-specific arms was replaced by a non-binding antibody arm). The CD47 monovalent bsAb, containing a CD47-binding arm and an irrelevant nonbinding arm, failed to induce notable phagocytosis (Figure 6a,b). The anti-MSLN monovalent bsAb, containing the same MSLN-binding arm as bsAb#1 and an irrelevant nonbinding arm, induced a substantial level of phagocytosis (maximal index of phagocytosis of 32.5, comparable to that of bsAb#1). However, the bsAb#1 was about 4.3-fold more potent than the monovalent anti-MSLN Ab in mediating phagocytosis of NCI-N87 cancer cells (EC50 of 2515 ng/mL vs 10794 ng/mL for bsAb#1 and the monovalent anti-MSLN, respectively) (Figure 6a). Interestingly, the potency of bsAb#2 in mediating ADCP was similar compared to its variant engaging monovalently MSLN (EC50 of 19.4 ng/mL vs 34.5 ng/mL for bsAb#2 and the monovalent anti-MSLN, respectively) (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Pairing a membrane-proximal epitope of MSLN to a CD47-blocking arm results in an efficient disruption of the CD47/SIRPα axis and enhances the phagocytosis potential of a MSLNxCD47 bsAb. ADCP dose-–response curve mediated by the CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 (a) or bsAb#2 (b) compared to their respective monovalent variants containing only the CD47 arm or anti-MSLN arm. A representative experiment (among four independent donors used as a source of effector cells) is depicted in the figure. In specific experiments, target cells were incubated in the presence of the indicated full length or F(ab’)2 fragments (tested at 10 μg/mL) (c). The anti-MSLN mAb 7D9 is tested at suboptimal concentration (3 ng/mL) either alone or combined to B6H12, CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 F(ab’)2 fragments (tested at 10 μg/ml each). Graph depicts a summary of four independent experiments (C). Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired T test: *p < .05, **p < .01, ns = not significant.

To investigate whether this benefit in ADCP observed with the bsAb#1 is not only related to a better co-engagement binding of CD47 and MSLN at the cell surface but also to a more efficient blockade of the CD47/SIRPα interaction, we generated F(ab′)2 fragments of bsAb#1, bsAb#2, and the anti-CD47 mAb B6H12. These F(ab′)2 fragments were then tested alone or in combination with a suboptimal concentration of the anti-MSLN antibody 7D9 (i.e., 3 ng/mL) in an ADCP assay using NCI-N87 cells as tumor target cells. 7D9 mAb, recognizing an epitope within region-II of MSLN, does not compete with bsAb#1 (recognizing region-I) or bsAb#2 (recognizing region-III). F(ab′)2 fragments of B6H12, CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 tested alone did not induce a significant increase in ADCP compared to the hIgG1 isotype control (Figure 6c). Lack of ADCP induced by these F(ab’)2 fragments confirm a crucial role of Fc-FcγR interaction in mediating phagocytosis of solid malignant tumor cells. However, combining F(ab’)2 fragments of B6H12 or CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 with anti-MSLN mAb 7D9, induced a significant increase in phagocytosis compared to that obtained with 7D9 alone (Figure 6c, index of phagocytosis of 28.1 vs 16.5, p = .026, and 29 vs 16.5, p = .0076, respectively). In contrast, F(ab’)2 of the CD47xMSLN bsAb#2 was unable to increase ADCP mediated by 7D9 (Figure 6c). These data suggest that pairing a membrane-proximal epitope of MSLN to a CD47 blocking arm in a bsAb format results in an augmented CD47/SIRPα blockade, allowing for more enhanced Fc-mediated ADCP.

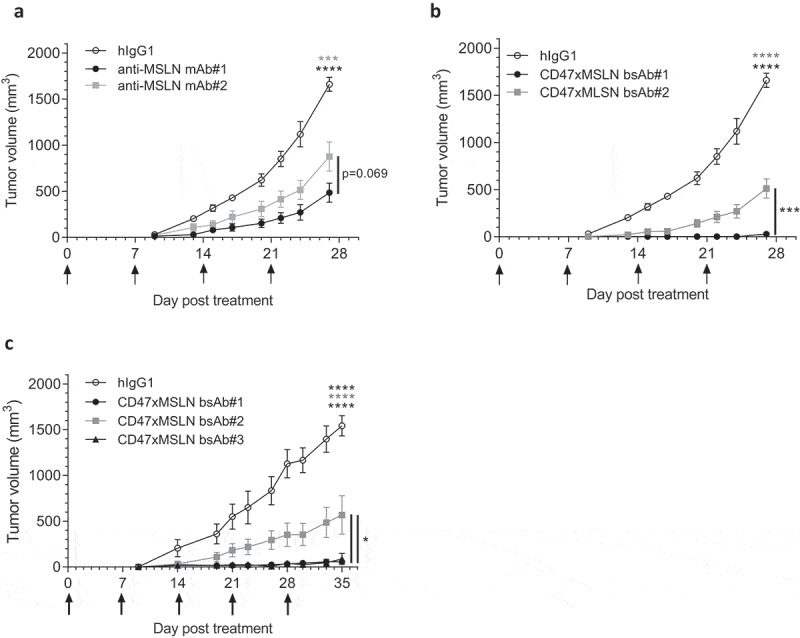

CD47xMSLN bsAbs targeting MSLN membrane-proximal domain confers optimal antitumor activity in vivo

We then extended our studies to in vivo tumor xenografts. Here, NOD scid mice were transplanted with the hepatocarcinoma cell line HepG2, transformed to express human MSLN and luciferase (HepG2-hMSLN-Red-Fluc). Compared to the hIgG1 isotype control, both anti-MSLN mAbs-#1 and -#2 induced significant tumor growth inhibition, with mAb#1 being slightly more effective at controlling tumor progression than mAb#2 without prolonging mouse survival (Figure 7a and Suppl Figure 8A). On the other hand, co-engagement of CD47 and MSLN with bsAb#1 resulted in complete inhibition of tumor growth (Figure 7b). In contrast, treatment with bsAb#2 only partially inhibited tumor growth (Figure 7b). bsAb#1 administration also significantly induced long-term tumor control compared to bsAb#2 (Suppl Figure 8B). Finally, even by increasing the dose up to 60 mg/kg, we confirmed that targeting a MSLN distal domain with bsAb#2 affords inferior control of tumor growth compared to bsAb#1 and bsAb#3 (engaging different epitopes in the MSLN membrane-proximal region), both of which providing similar increased anti-tumor efficacy and survival (Figure 7c and Suppl Figure 8 C). Taken together, these data corroborate our in vitro findings on improved tumoricidal activities of CD47xMSLN bsAbs targeting a MSLN proximal epitope, translating into improved tumor control in vivo.

Figure 7.

Antitumor activity of anti-MSLN mAbs and CD47xMSLN bsAbs in a xenograft model. HepG2-MSLN-Red-Fluc tumor cells were injected s.c. in the right flank of NOD scid mice. Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed 2 weeks after the graft to measure tumor burden and then mice were subsequently allocated into different groups to obtain similar mean tumor burden between groups. From the next day, antibody treatments were administered once a week i.v. at 6 mg/kg (a, b) or 60 mg/kg (c) starting the day after BLI (D15). Tumor size was measured 3 times a week using a digital caliper and tumor volume determined using the formula (lengthxwidth2) x 0.5. The endpoint of the experiment was fixed at 1500 mm3. Tumor volume is represented as mean ± SEM (n = 7–8 mice/group) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison statistical analysis performed at D27 (A, B) or D35 (C). *p < .05, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001, ns = not significant.

Discussion

We investigated the impact of the epitope location of anti-MSLN mAbs and anti-CD47xMSLN bsAbs on Fc-mediated effector functions (i.e., ADCC and ADCP). Targeting a membrane-proximal region with anti-MSLN mAbs resulted in more efficient ADCC, but similar ADCP, compared to targeting membrane-distal regions. Interestingly, the bsAb targeting a membrane-proximal MSLN epitope and CD47 resulted in higher levels of ADCC and ADCP at the maximum concentration tested. These observations were translated in vivo into a more efficacious control of tumor growth by CD47xMSLN bsAbs targeting a membrane-proximal MSLN epitope in xenograft tumor models.

Increasing evidence suggests that the location of antibody binding epitopes is important for the activity of mAb-dependent effector cell activity, with membrane-proximal domains being more potent at inducing NK and T cell-mediated killing. This has been demonstrated for several TAA, using mAbs and T cell retargeting bsAbs, in hematological (e.g., CD20, CD307) and solid (e.g., glypican-3, ROR1) malignancies.11,13,15,36,37 The high-affinity anti-MSLN mAb amatuximab has demonstrated limited efficacy as a single agent in patients.16,38 As it is known that amatuximab binds to an epitope in the N-terminal end of MSLN, presumed to be far away from the cell membrane, the epitope location may not be optimal for anti-tumor effector functions.30 A MSLN membrane proximal targeted immunotoxin (YP218) has been reported to have potent tumoricidal activities in solid tumors.39 In addition, by comparing two types of CAR-T cells targeting either the region-I or the region-III of MSLN, Qian and colleagues demonstrated recently that the membrane-proximal region of MSLN is a promising epitope to target for solid tumor using CAR T-cell therapy.40

The precise conditions that define the activation threshold of NK cells are so far not clearly understood. Binding to a membrane-proximal epitope on MSLN may allow Abs to be in a position or orientation that may reduce the synaptic cleft between NK cells and opsonized tumor cells. As such, perforin and other lytic effector molecules would be secreted/concentrated within a stable immune synapse for efficient killing.41,42 With reporter cell assays, we show that targeting a membrane-proximal epitope resulted in preferential activation of the FcγR-IIIA, but not FcγR-I or -IIA, as compared to targeting a membrane-distal epitope. This may suggest that engaging a membrane-proximal epitope on target cells directly favors FcγR-IIIA interaction on effector cells. Therefore, our data complement published reports by highlighting that, in addition to improving tumor killing by ADCC, targeting a membrane-proximal epitope on the TAA, such as MSLN, preferentially optimizes FcγR-IIIA signaling in effector cells.11,13

We also show that targeting a membrane-proximal epitope with an anti-MSLN mAb does not translate into more efficient phagocytosis of tumor cells. In line with this finding, FcγR-IIA, thought to be a dominant player in inducing ADCP, is similarly activated by target cells opsonized with anti-MSLN mAbs regardless of their epitope specificity (e.g., membrane-proximal or -distal).35 On the contrary, Fletcher and colleagues demonstrated that Abs binding to a membrane-proximal epitope improved phagocytosis by a murine macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7.43 This discrepancy could be explained by the different antigens or in vitro models used in the two studies. In our study, the antigen (e.g., MSLN) is natively expressed on live target cells, whereas to determine the effect of epitope location on phagocytosis, Fletcher and colleagues used particles engrafted with antigen (e.g., CEA) to mimic a cell surface target.43 Therefore, this model may not integrate all molecular interactions between macrophages and target cells leading to the final immune synapse formation. Indeed, phagocytosis is proposed to proceed through a “zippering” mechanism where several integrin interactions between macrophages and target cells allow for progressive exclusion of the phosphatase CD45 from the immune synapse and promote efficient binding and stabilization of FcγR-Fc complexes.44,45 Considering the reported importance of macrophages as critical effectors of Ab therapies for cancer, additional approaches to enhance antibody-induced macrophage effector functions are being considered.34,46 One approach is to increase binding of Ab Fc fragments to FcγRs, and consequently improve macrophage phagocytosis.47-49 One such anti-MSLN mAb (Ab237) has been described with an Fc-enhanced domain, resulting in improved ADCP in vitro and increased in vivo anti-tumor efficacy compared to its wild-type Fc variant.50 An alternative and popular strategy currently being tested is to target the CD47/SIRPα axis.22-24,27 Since F(ab′)2 fragments can only block CD47, but not induce ADCP due to the lack of Fc portion, we used F(ab′)2 fragments of CD47xMSLN bsAbs to show that the bsAb targeting the MSLN membrane-proximal epitope can synergize with an FcγR-activating antibody to provide superior phagocytosis efficacy.

These mechanistic studies unravel a previously unappreciated role for epitope specificity of CD47xMSLN bsAbs, and suggest that targeting a membrane-proximal epitope of MSLN affords more efficient CD47/SIRPα blockade by the CD47xMSLN bsAb, resulting in enhanced ADCP. Recent data have demonstrated that phagocytosis is a multi-layered mechanism of receptor synergy that allows the macrophage to fine-tune its response.44,45 Indeed, conformational changes upon FcγR-engagement induce phosphorylation of the Fc receptor’s immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), thereby initiating a signaling cascade that promotes phagocytosis. Downstream signaling involves kinases-mediated phosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins, including myosin-II, which drives assembly of the synaptic cup and promotes cell uptake. Phosphorylation of FcγR ITAMs was demonstrated to be balanced by inhibitory signaling from the CD47/SIRPα axis, likely SHP1 phosphatases, that would cleave phosphatase groups from ITAMs of the FcγR.51-54 Additionally, SHP-1 activation mediated by CD47/SIRPα signaling inactivates myosin-II.55 Further investigations would be needed to study the effects of such CD47xMSLN bsAbs on the above mentioned signaling cascades.

Targeting the membrane-proximal domain with an anti-MSLN mAb in vivo showed an improved ability to control tumor growth in the MSLN-transfected hepatocarcinoma xenograft model in NOD scid mice. The results suggest that ADCC may be involved in controlling MSLN-positive tumor growth, but may not be the dominant effector function in such in vivo model where the ADCC NK effector cells are known to be deficient. To better assess the in vivo contribution of NK cells, additional models with functional NK cells, such as NOG-IL2 or NOG-IL15 transgenic mice, would be useful.56,57

The membrane-proximal CD47xMSLN bsAb demonstrated more potent anti-tumor efficacy in vivo compared to the CD47xMSLN bsAb targeting a membrane-distal region of MSLN. Furthermore, the membrane proximal bsAb were also more efficacious at controlling tumor growth than the control anti-MSLN mAb (targeting the same MSLN epitope). As SIRPα of NOD scid mice recognizes human CD47 and effectively prevents the engulfment of human cells by mouse macrophages, the enhanced anti-tumor efficacy achieved by targeting a MSLN membrane-proximal epitope with a CD47xMSLN bsAb could be mediated by affording optimized blockade of CD47/SIRPα axis in addition to MSLN targeting, which outperforms treatment with the monospecific anti-MSLN antibody.58

Together, this work demonstrated that when designing antibody-based molecules, the targeting domain on a TAA needs to be carefully considered to ensure maximal effector function. In the context of MSLN-positive solid tumors, we showed that an approach targeting a membrane-proximal epitope coupled to a blocking CD47 arm afforded improved ADCC and ADCP profile that translated into increased in vivo efficacy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Human cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The gastric, lung, and liver carcinoma cell lines, NCI-N87, NCI-H226, and HepG2, respectively, were cultured in RPMI 1640 or MEM (Sigma Aldrich, R8758) media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma Aldrich, F7524) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma Aldrich, G7513). The HepG2-hMSLN-Red-Fluc cell line was developed by transfecting wild-type HepG2 cells with an internal ribosome entry site-containing tricistronic vector encoding human MSLN, Red Firefly luciferase (Fluc) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequences. The transgene was inserted by targeting specifically the human Rosa26 locus using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Stably expressing pool was obtained by successive flow cytometry cell sorting of GFP positive cells (Beckman Coulter, MoFlo Astrios), and clones were then generated by single-cell sorting in the absence of selective pressure. Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 and used between passage 5 and 15.

Antibodies

The sequences of the anti-MSLN arm of the CD47xMSLN bsAbs were isolated from our phage display platform, using proprietary fixed VH libraries with variable λ light chains and screening was performed using a combination of recombinant human MSLN proteins (produced in-house) and cells expressing human MSLN. Selected sequences were then reformatted into human IgG1 monoclonal Abs. These anti-MSLN Abs share identical heavy chain variable domains, but have unique λ light chain variable domains (Suppl Table 1). Therefore, in contrast to classical anti-MSLN mAbs, the specificity of these mAbs against MSLN is driven by the variable λ-light chain domains. The anti-CD47 arm of the bsAb was generated with similar technology using proprietary fixed VH libraries with variable κ light chains (Suppl Table 1). To generate the κλ body CD47xMSLN bispecific Abs, a selected and common variable κ light chain targeting CD47 and the aforementioned anti-MSLN λ-light chains were assembled with a common human IgG1 heavy chain, giving rise to fully human IgG1 CD47xMSLN bsAbs. These bsAbs were produced by cloning one fixed heavy chain and two light chains (one κ and one λ) into a single mammalian expression vector. The resulting bsAb was purified using a 3-step industrial-scale process as described in detail by Fischer and colleagues.59 The bsAb human IgG molecules were assembled naturally without the requirement of mutations or linkers (Suppl Figure 9). The anti-CD47 monovalent antibody used in this study contains the same CD47-binding arm as the CD47xMSLN bsAbs and an arm binding to an irrelevant target. The anti-MSLN monovalent antibodies contain the same MSLN-binding arm as the respective CD47xMSLN bsAbs (according to the binding domain recognized on MSLN) and an irrelevant nonbinding arm (with no detectable binding to any known human protein). Human IgG1 (hIgG1) isotype control mAb was generated internally from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) culture supernatant. The anti-mesothelin monoclonal antibody amatuximab (MORAB-009, Morphotek), 22A10 and 7D9 (both from Genentech) were cloned and expressed as human IgG1 in CHO cells.

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

Human PBMCs from healthy volunteers, used as effector cells, were cultured in flasks at 1–2 × 106 cells/mL and activated overnight at 37°C with medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-2 (Peprotech, 200–02). The day after, 5000 malignant NCI-N87 target cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 100 μCi Cr51. After washing, malignant cells were then opsonized with a dose range of Abs or a fixed dose (e.g., 1 μg/mL) of an irrelevant hIgG1 for 30 min at 37°C. 5ʹ000 Cr51-loaded target cells were then mixed with 400,000 PBMC effector cells to obtain the final 80:1 ratio between effector (PBMC) and target cells (NCI-N87 cells). The cell mixture was incubated for 4 h at 37°C before being centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 rpm. Twenty-five microliter supernatant was transferred in a Lumaplate (coated with scintillant) and counted in a γ-counter. Negative controls (spontaneous Cr51 release) consisted of Cr51-loaded target cells incubated with medium in the absence of effector cells. Total lysis control consisted of Cr51-loaded target cells incubated with 5 μL of cell lysis solution (Triton X-100). Nonspecific lysis control (baseline) consisted of Cr51-loaded target cells incubated with effector cells, without any Ab addition. ADCC reaction was performed in triplicates. The ADCC percentage was calculated using the following formula: %ADCC = ((sample cpm – nonspecific lysis control cpm)/(total lysis control cpm – neg control cpm)) x 100%.

Antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis

PBMCs were isolated from buffy coats by Ficoll gradients (StemCell Technologies, 85450). Macrophages were generated by culturing PBMCs for 7 days in complete medium (RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 25 μg/mL gentamicin) (all from Sigma Aldrich), and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol in the presence of 20 ng/mL of human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (Peprotech, 300–25). After macrophages differentiation, plated macrophages were stained using calcein red-orange (Invitrogen, C34851). For phagocytosis to proceed, calcein-AM-labeled malignant NCI-N87 cells were opsonized with a dose range of anti-MSLN mAbs, CD47xMSLN bsAbs or a fixed-dose (e.g., 100 μg/mL) of an irrelevant hIgG1 for 30 min at 37°C before being added to macrophages. The opsonized target cells were then added to obtain the final 1:1 ratio between effector (macrophages) and target cells (NCI-N87 cells) in the presence of an excess of a nonspecific human IgG (1 mg/mL). Phagocytosis experiments were performed with 3 × 104 macrophages and 3 × 104 target cells per well. The cell mixture was incubated for 2.5 h at 37°C. Cells were finally analyzed using the CellInsight imaging platform (CX5, ThermoFisher) associated with the HCS software to calculate the index of phagocytosis. This index is defined as the number of malignant cells engulfed per 100 macrophages. In specific experiments, F(ab′)2 fragments of the anti-CD47 mAb, B6H12, the CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 (all hIgG1) were generated (Suppl Figure 10) and tested alone or combined to a suboptimal concentration of the anti-MSLN mAb 7D9 (e.g., 3 ng/mL) in the aforementioned ADCP assay using M-CSF macrophages and NCI-N87 cells as tumor target cells. 7D9 mAb was chosen because it does not interfere with bsAb#1 or bsAb#2 for their binding to MSLN-positive cells.

FcγR-reporter assays

FcγRs signaling were evaluated by FcγR-I, FcγR-IIA (H131) or FcγR-IIIA (V158) reporter cell lines as instructed by the manufacturer (Promega, G9901, G7015). Briefly, 12500 NCI-N87 cells per well were mixed with 75000 engineered-reporter cell lines in which the activation of FcγR-I, -IIA, or -IIIA leads to the expression of a luciferase reporter. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate with serially diluted anti-MSLN mAbs or anti-CD47xMLN bsAbs. After incubation for 6 h at 37°C, luciferase activities were measured by using ONE-Glo Luciferase assay system (Promega, E6110) and the Fluostar Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer). The FcγRs signaling mediated by antibodies were expressed as fold of activation of luciferase signals over that without tested antibody added.

Antibody binding assay

Comparative binding curves of anti-MSLN mAbs or CD47xMSLN bsAbs were performed using NCI-N87 cells by flow cytometry. For this purpose, mAbs were conjugated with reactive Alexa-Fluor 488 (AF488) according to manufacturer procedures (Invitrogen, A-20181). Covalent conjugation was made wrapped in foil and incubated for 1.5 h with gentle rotation at room temperature, unreacted AF488 was removed and Abs were exchanged into storage buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4). Cells were resuspended at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL in PBS + bovine serum albumin (BSA) 2%, and incubated with a serial dilution of in-house AF488-labeled Abs. At this point, cells were kept at 4°C to prevent target internalization. Washing and paraformaldehyde-fixation of cells was avoided due to the potential effect on Ab dissociation rates. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C before being analyzed on a flow cytometer (Cytoflex, Beckman Coulter). The curves were fitted with a sigmoidal dose–response equation and EC50 values were calculated by the Prism 5 program. Competition binding assays were carried out using NCI-N87 cells. Cells were resuspended at 0.5 × 106 cells/mL in PBS + BSA2%, and incubated with a mixture of 10 μg/mL (final concentration) of in house AF488-labeled anti-MSLN Abs (e.g., amatuximab, 22A10, 7D9 or CD47xMSLN bsAb#1) and a serial dilution of unlabeled anti-MSLN Abs (anti-MSLN mAb#1, mAb#2, anti-CD47xMSLN bsAb#1 or bsAb#3). Cells were incubated 10 min at 4°C and analyzed on a flow cytometer and FlowJo software.

In vivo efficacy experiments

Immunodeficient NOD scid female mice, aged 7- to 9-week-old at experiment initiation, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Saint-Germain-Nuelles, France) and maintained under specific pathogen-free condition. After arrival, animals were housed for 1 week to allow them to adapt their new environment. Animal facility and experiments were approved by the animal research committee of Geneva canton and experiments performed in accordance with the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office guidelines. 3.106 HepG2-hMSLN-Red-Fluc cells were injected subcutaneously in 100 µl of sterile PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) into the right flank of NOD scid mice. After 14 days, tumor measurement was performed by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (IVIS Lumina LT, Perkin Elmer) to constitute groups of mice with an equivalent mean tumor burden. BLI acquisitions were performed by intraperitoneal injection of 300 µL luciferin substrate (10 mg/kg, Perkin Elmer). Data were analyzed with the living image software (Perkin Elmer). From day 15, mice received one injection per week of 6 or 60 mg/kg of the specified antibodies by i.v. administration (tail vein in 100 µl) until the endpoint of the experiment (tumor volume = 1500 mm3). Mice were then monitored for tumor development 3 times a week and tumors measured by a digital caliper. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: (length x width2) x 0.5. For survival curve experiments, antibody treatment continued until the tumor reached a tumor volume of 1500 mm3, which was considered the endpoint of the experiment.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 was used for all statistical analysis. The unpaired student t test or one-way ANOVA test were used as specified for comparing the difference between groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Log-rank test was used for Kaplan–Meier survival curves. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Abbreviations

- Aa

Amino acid

- ADCC

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity

- ADCP

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis

- AF488

Alexa-Fluor 488

- bsAb

Bispecific Antibody

- BLI

Bioluminescence Imaging

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- CAR-T

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T

- CEA

Arcinoembryonic Antigen

- CD

Cluster of Differentiation

- CHO

Chinese Hamster Ovary

- Cr51

Chromium 51

- EC50

Half maximal Effective Concentration

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Fab

Fragment Antigen-Binding

- Fc

Fragment Crystallizable

- FCS

Fetal Calf Serum

- FcγR

Fc gamma Receptor

- GFP

Green Fluorescent Protein

- GPI

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HCS

High Content Screening

- HEPES

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)Piperazine-1-EthaneSulfonic acid

- IgG

Gamma Immunoglobulin

- IL

Interleukin

- ITAM

Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Activation Motif

- kD

Kilo Dalton

- mAb

Monoclonal Antibody

- M-CSF

Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

- MEM

Minimum Essential Medium Eagle

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Intensity

- min

Minutes

- MSLN

Mesothelin

- NOD scid

NonObese Diabetic Several Combined ImmunoDeficient

- NK cells

Natural Killer cells

- PBS

Phosphate Buffer Saline

- PBMCs

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

- rpm

Rotation per minute

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- RT

Room Temperature

- SABC

Specific Antigen Binding Capacity

- SEM

Standard Error of the Mean

- SIRP-α

Signal Regulatory Protein alpha

- TAA

Tumor Associated Antigen

- vs

Versus

Acknowledgments

E.H., X.C., V.B., and L.S. were involved in designing the study plan. E.H., X.C., F.R., L.B., V.M., L.C., Lu.B, G.P., T.B., F.J., S.C., N.B. and M.C. were involved in data collection and interpretation of data. E.H. and X.C. were involved in writing the manuscript. K.M., V.B. and L.S. were involved in revising the manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge Laura Cons, Ulla Ravn, Anne Papaioannou, Franck Gueneau, Giovanni Magistrelli and Yves Poitevin for their valuable technical assistance.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All co-authors are employees of Light Chain Bioscience/Novimmune S.A., whose anti-MSLN mAbs and CD47xMSLN bsAbs were used in this study.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Carter PJ, Lazar GA.. Next generation antibody drugs: pursuit of the ‘high-hanging fruit’. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:197–13. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicodemus CF. Antibody-based immunotherapy of solid cancers: progress and possibilities. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:923–39. doi: 10.2217/imt.15.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corraliza-Gorjón I, Somovilla-Crespo B, Santamaria S, Garcia-Sanz JA, Kremer L. New strategies using antibody combinations to increase cancer treatment effectiveness. Front Immunol. 1804;2017(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplon H, Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2019. mAbs. 2019;11:219–38. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1556465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chames P, Baty D. Bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy: the light at the end of the tunnel? mAbs. 2009;1:539–47. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labrijn AF, Janmaat ML, Reichert JM, Parren PWHI. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccione EC, Juarez S, Liu J, Tseng S, Ryan CE, Narayanan C, Wang L, Weiskopf K, Majeti R. A bispecific antibody targeting CD47 and CD20 selectively binds and eliminates dual antigen expressing lymphoma cells. mAbs. 2015;7:946–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dheilly E, Moine V, Broyer L, Salgado-Pires S, Johnson Z, Papaioannou A, Cons L, Calloud S, Majocchi S, Nelson R, et al. selective blockade of the ubiquitous checkpoint receptor cd47 is enabled by dual-targeting bispecific antibodies. Mol Ther. 2017;25:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buatois V, Johnson Z, Salgado-Pires S, Papaioannou A, Hatterer E, Chauchet X, Richard F, Barba L, Daubeuf B, Cons L, et al. Preclinical development of a bispecific antibody that safely and effectively targets CD19 and CD47 for the treatment of b-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1739–51. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatterer E, Barba L, Noraz N, Daubeuf B, Aubry-Lachainaye JP, von der Weid B, Richard F, Kosco-Vilbois M, Ferlin W, Shang L, et al. Co-engaging CD47 and CD19 with a bispecific antibody abrogates B-cell receptor/CD19 association leading to impaired B-cell proliferation. mAbs. 2019;11:322–34. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1558698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleary KLS, Chan HTC, James S, Glennie MJ, Cragg MS. Antibody distance from the cell membrane regulates antibody effector mechanisms. J Immunol. 2017;198:3999–4011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beers SA, Chan CHT, French RR, Cragg MS, Glennie MJ. CD20 as a target for therapeutic type I and II monoclonal antibodies. Semin Hematol. 2010;47:107–14. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano K, Orita T, Nezu J, Yoshino T, Ohizumi I, Sugimoto M, Furugaki K, Kinoshita Y, Ishiguro T, Hamakubo T, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cragg MS, Morgan SM, Chan HT, Morgan BP, Filatov AV, Johnson PW, French RR, Glennie MJ. Complement-mediated lysis by anti-CD20 mAb correlates with segregation into lipid rafts. Blood. 2003;101:1045–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Stagg NJ, Johnston J, Harris MJ, Menzies SA, DiCara D, Clark V, Hristopoulos M, Cook R, Slaga D, et al. Membrane-proximal epitope facilitates efficient t cell synapse formation by Anti-FcRH5/CD3 and is a requirement for myeloma cell killing. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:383–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldo P, Cecco S. Amatuximab and novel agents targeting mesothelin for solid tumors. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:5337–53. doi: 10.2147/OTT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golfier S, Kopitz C, Kahnert A, Heisler I, Schatz CA, Stelte-Ludwig B, Mayer-Bartschmid A, Unterschemmann K, Bruder S, Linden L, et al. Anetumab Ravtansine: A novel mesothelin-targeting antibody-drug conjugate cures tumors with heterogeneous target expression favored by bystander effect. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1537–48. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho M, Feng M, Fisher RJ, Rader C, Pastan I. A novel high-affinity human monoclonal antibody to mesothelin. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2020–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scales SJ, Gupta N, Pacheco G, Firestein R, French DM, Koeppen H, Rangell L, Barry-Hamilton V, Luis E, Chuh J, et al. An anti-mesothelin-monomethyl auristatin e conjugate with potent antitumor activity in ovarian, pancreatic, and mesothelioma models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2630–40. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0487-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hara M, Stashwick C, Haas AR, Tanyi JL. Mesothelin as a target for chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells as anticancer therapy. Immunotherapy. 2016;8:449–60. doi: 10.2217/imt.16.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Advani R, Flinn I, Popplewell L, Forero A, Bartlett NL, Ghosh N, Kline J, Roschewski M, LaCasce A, Collins GP, et al. CD47 blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and rituximab in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1711–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiskopf K, Jahchan NS, Schnorr PJ, Cristea S, Ring AM, Maute RL, Volkmer AK, Volkmer JP, Liu J, Lim JS, et al. CD47-blocking immunotherapies stimulate macrophage-mediated destruction of small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2610–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI81603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, Wang J, Contreras-Trujillo H, Martin R, Cohen JD, et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:6662–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiskopf K, Ring AM, Ho CC, Volkmer JP, Levin AM, Volkmer AK, Ozkan E, Fernhoff NB, van de Rijn M, Weissman IL, et al. Engineered SIRPα variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science. 2013;341:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1238856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikic BI, Lakhani N, Patnaik A, Shah SA, Chandana SR, Rasco D, Colevas AD, O’Rourke T, Narayanan S, Papadopoulos K, et al. First-in-human, first-in-class phase I trial of the anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:946–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Myklebust JH, Varghese B, Gill S, Jan M, Cha AC, Chan CK, Tan BT, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. 2010;142:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Jan M, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, Zhao F, Park CY, Weissman IL, Majeti R. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1374–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneko O, Gong L, Zhang J, Hansen JK, Hassan R, Lee B, Ho M. A binding domain on mesothelin for CA125/MUC16. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3739–49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806776200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennis M, Carlos S, Spencer SD, Zhang Y. Anti-mesothelin antibodies and immunoconjugates. Patent US 8,911,732 B2, 2014

- 30.Ma J, Tang WK, Esser L, Pastan I, Xia D. Recognition of mesothelin by the therapeutic antibody morab-009: structural and mechanistic insights. J Biol Chem. 2012. September 28;287(40):33123–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veillette A, Chen J. SIRPα–CD47 Immune Checkpoint blockade in anticancer therapy. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:173–84. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matlung HL, Szilagyi K, Barclay NA, van den Berg TK. The CD47-SIRPα signaling axis as an innate immune checkpoint in cancer. Immunol Rev. 2017;276:145–64. doi: 10.1111/imr.12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gul N, van Egmond M. Antibody-dependent phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages: a potent effector mechanism of monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5008–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiskopf K, Weissman IL. Macrophages are critical effectors of antibody therapies for cancer. mAbs. 2015;7:303–10. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richards JO, Karki S, Lazar GA, Chen H, Dang W, Desjarlais JR. Optimization of antibody binding to FcgRIIa enhances macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2517–27. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hombach AA, Schildgen V, Heuser C, Finnern R, Gilham DE, Abken H. T Cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: the position of the binding epitope within the target molecule determines the efficiency of activation of redirected t cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4650–57. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi J, Li X, Peng H, Cook EM, Dadashian EL, Wiestner A, Park H, Rader C. Potent and selective antitumor activity of a T cell-engaging bispecific antibody targeting a membrane-proximal epitope of ROR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:E5467–E5476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719905115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao X-Y, Subramanyam B, Sarapa N, Golfier S, Dinter H. Novel antibody therapeutics targeting mesothelin in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Drugs. 2016;3:76–86. doi: 10.2174/2212697X03666160218215744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang YF, Phung Y, Gao W, Kawa S, Hassan R, Pastan I, Ho M. New high affinity monoclonal antibodies recognize non-overlapping epitopes on mesothelin for monitoring and treating mesothelioma. Sci Rep. 2015. May;21(5):9928. doi: 10.1038/srep09928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z 2, Jiang D, Yang H, He Z, Liu X, Qin W, Li L, Wang C, Li Y, Li H, et al. Modified CAR T cells targeting membrane-proximal epitope of mesothelin enhances the antitumor function against large solid tumor. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:476. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1711-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orange JS. Formation and function of the lytic NK-cell immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:713–25. doi: 10.1038/nri2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCann FE, Vanherberghen B, Eleme K, Carlin LM, Newsam RJ, Goulding D, Davis DM. The size of the synaptic cleft and distinct distributions of filamentous actin, ezrin, CD43, and CD45 at activating and inhibitory human NK cell immune synapses. J Immunol. 2003;170:2862–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakalar MH, Joffe AM, Schmid EM, Son S, Podolski M, Fletcher DA. Size-dependent segregation controls macrophage phagocytosis of antibody-opsonized targets. Cell. 2018. June 28;174(1):131–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freeman SA, Goyette J, Furuya W, Woods EC, Bertozzi CR, Bergmeier W, Hinz B, van der Merwe PA, Das R, Grinstein S, et al. Integrins form an expanding diffusional barrier that coordinates phagocytosis. Cell. 2016;164:128–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodridge HS, Underhill DM, Touret N. Mechanisms of fc receptor and dectin-1 activation for phagocytosis: mechanisms of Fc Receptor and Dectin-1 activation for phagocytosis. Traffic. 2012;13:1062–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poh AR, Ernst M. Targeting macrophages in cancer: from bench to bedside. Front Oncol. 2018;8:49. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herter S, Birk MC, Klein C, Gerdes C, Umana P, Bacac M. Glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies enhances monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytosis and cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2014;192:2252–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S, Vafa O, Peng JS, Hyun L, Chan C, Chung HS, Eivazi A, Yoder SC, et al. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:4005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508123103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horton HM, Bernett MJ, Pong E, Peipp M, Karki S, Chu SY, Richards JO, Vostiar I, Joyce PF, Repp R, et al. Potent in vitro and in vivo activity of an Fc-engineered anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody against lymphoma and leukemia. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8049–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fanslow WCKozlosky C, JM Gudas. Anti-mesothelin binding proteins. Patent US 2014/0004121 a1; 2014. January.

- 51.Oldenborg P-A, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) regulates Fcg and complement receptor–mediated phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 2001. April 2;193(7):855–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okazawa H, Motegi S, Ohyama N, Ohnishi H, Tomizawa T, Kaneko Y, Oldenborg PA, Ishikawa O, Matozaki T. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J Immunol. 2005. February 15;174(4):2004–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kant AM, De P, Peng X, Yi T, Rawlings DJ, Kim JS, Durden DL. SHP-1 regulates Fcg receptor–mediated phagocytosis and the activation of RAC. Blood. 2002. 1;100(5):1852–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai RK, Discher DE. Inhibition of “self” engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:989–1003. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katano I, Takahashi T, Ito R, Kamisako T, Mizusawa T, Ka Y, Ogura T, Suemizu H, Kawakami Y, Ito M. Predominant development of mature and functional human NK cells in a novel human IL-2–producing transgenic NOG mouse. J Immunol. 2015;194:3513–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katano I, Nishime C, Ito R, Kamisako T, Mizusawa T, Ka Y, Ogura T, Suemizu H, Kawakami Y, Ito M, et al. Long-term maintenance of peripheral blood derived human NK cells in a novel human IL-15- transgenic NOG mouse. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17230. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kwong LS, Brown MH, Barclay AN, Hatherley D. Signal-regulatory protein α from the NOD mouse binds human CD47 with an exceptionally high affinity - implications for engraftment of human cells. Immunology. 2014;143:61–67. doi: 10.1111/imm.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fischer N, Elson G, Magistrelli G, Dheilly E, Fouque N, Laurendon A, Gueneau F, Ravn U, Depoisier JF, Moine V, et al. Exploiting light chains for the scalable generation and platform purification of native human bispecific IgG. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6113. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.