Abstract

A new study sheds light on how sensitivity to communication sounds is established in the brain. Juvenile finches raised with tutors of either the same or different species always learned the tutors’ songs. Cortical neurons developed selectivity for the learned song by tuning for its secondary acoustic features.

Although humans are born with equal propensity for any language at birth, our brains become specialized for the language that we hear the most from our caregivers early on no matter the language of our biological parents. Over the first year of our life, our understanding of the syllables of our native language improves, at the cost of impaired discrimination of syllables from a different language1. As adults, our brains reflect the specialization for our native language, driving stronger responses in the auditory cortex for speech, as compared to other sounds. Importantly, the representation of language in the brain mirrors the phonetic structure of the native language2. This specialization is at the core of our ability to communicate. It remains unknown, however, what specific developmental transformations our auditory system undergoes to establish this selectivity, which may be partially learned and partially innate3. Moore and Woolley4 bring a creative approach to this complex question.

Specialization for communication signals is not unique to humans. Indeed, songbirds communicate using complex songs that they learn from their tutor (typically their parent), and their auditory system exhibits exquisite sensitivity to their species’ songs. Songbirds can be raised in controlled acoustic environments, such that they learn the song from their tutor over weeks 3–6, fully developing their own song by week 9 of their life5. Moore and Woolley4 used songbirds to ask some fundamental questions about where and how sensitivity to the animal’s communication signals arises in the brain.

In an elegant behavioral experimental design, the authors focused on three species of finches: zebrafinches, long-tailed finches, and Bengalese finches. Each of these species speaks a different “language,” or, more accurately, produces a distinctive spectro-temporally complex song. In a custom-built environment, the authors raised juvenile birds in enclosures with tutors of either the same (conspecific tutor) or different species (heterospecific tutor)6 and recorded their songs and responses in the pupils’ brains to songs of the three species. This experimental design would be similar to comparing how well children respond to and speak French as adults, depending on whether they were born of or adopted from other countries by French-speaking parents. In the brain, the responses to the song that are innate should be the same for con- and cross-tutored birds of the same species, whereas learned responses should be different in con- and cross- tutored birds.

First, the experimenters asked whether the birds were able to learn the song of a heterospecific tutor. The songs of finches are composed of sequences of “syllables”, much like human speech. Pupils learn the syllables from the tutor but arrange them in new sequences, creating their own characteristic song. The authors used two different species of finches as nestlings but the same species of heterospecific tutor (Bengalese finch), which allowed the authors to compare the song that the birds produced as adults between the two species. The authors found that all pupils learned the song of their tutor, regardless of whether the tutor was con- or heterospecific, and that the pupils of either species learned the Bengalese finch song equally well, although perhaps slightly worse than a Bengalese finch pupil. This is not unlike an internationally adopted child learning to speak the language of their adoptive parents. These behavioral results lay the groundwork for the electrophysiological exploration of the responses to songs in the songbird auditory system.

The authors tested where in the auditory pathway the preference for the learned song in normally raised birds emerges. In mammals, some studies found that neurons in the auditory cortex exhibit specialization for conspecific vocalizations7, 8, whereas other studies found conflicting results9. Neurons in the auditory areas in the songbird exhibit response properties consistent with the hierarchical organization of the auditory cortex in mammals10: Latencies of responses, sparseness and selectivity, and noise correlations increase along the hierarchy11. Furthermore, the avian auditory cortex exhibits a similar network architecture, comprised of excitatory principal cells and inhibitory interneurons whose action potential shapes, firing rates, and receptive field structure mirror those of the mammalian auditory cortex11. Therefore, the authors focused on the brain areas that are homologous to the input and output layers of the primary and secondary auditory cortex.

The authors found selectivity for the conspecific song in the deep primary and secondary cortical areas in normally reared birds. Because this selectivity was not observed for the thalamo-recipient primary cortical area, the authors concluded that selectivity for the birdsong emerges in the primary auditory cortex. Was this selectivity innate or did it emerge with learning? This is the key question that the experimenters were now able to answer by comparing neuronal responses to songs of birds of the same species reared by either con- or heterospecific tutors. In the deep regions of the primary and in secondary cortical regions, the preference for the conspecific song shifted toward tutor song in cross-tutored pupils. These results suggested that the selectivity for the song is not innate, but rather experience-dependent.

How does this specificity come about? The authors characterized the responses of neurons to different spectro-temporal patterns of sounds. Since each species’ birdsong has a distinct, identifiable spectro-temporal structure, one way for the representation to develop would be through tuning to specific spectro-temporal features of the appropriate tutor songbird. The authors defined a set of spectro-temporal ripples that were characteristic of the songs from different species. In the intermediate auditory cortex, there was no preference for any spectro-temporal ripple parameters. By contrast, in the deep primary cortical area, the preference for the tutor spectro-temporal structure emerged and was preserved in the secondary auditory areas. Ultimately, response profiles in the deep primary cortical region were more similar between heterospecific birds cross-tutored by the same single species, as compared to conspecific birds reared by two different species.

The preference for the modulation of the spectro-temporal ripples correlated with the responsiveness to songs of the specific tutor. The results suggest that the tuning in the auditory cortical neurons is adjusted to match secondary spectro-temporal statistics of the song, similar to that found in the rat12. Selectivity for the secondary spectro-temporal modulations emerges as fundamental aspect of auditory processing of communication signals, and learning a set of communication signals leads to adjustment of these response parameters.

Altogether, these results provide insight into how aspects of innate and learned auditory processing combine to allow improved sensitivity to behaviorally-relevant sounds. This improved understanding would be best tested by constructing a predictive model of neural responses to con- and heterospecific songs – a model that incorporates the spectrotemporal tuning preferences optimal to the song13, known neural and anatomical connectivity patterns, and even excitatory-inhibitory dynamics and firing rate characteristics. Furthermore, the results of this paper will be useful for correlating neural dynamics with behavioral tasks14. It is reasonable to speculate that the observed increased sensitivity to conspecific or heterospecific sound patterns would correlate with improved conspecific or heterospecific song discrimination, respectively, and even motor vocalization. Finally, the results of this paper have implications for human language processing, hinting at neural mechanisms for auditory language acquisition and processing. Our ability to interrogate neural processes in the human brain is increasing in spatial and temporal resolution, so reconciling these avian model results with innovative approaches in humans can improve our understanding of language processing, speech disorders, and neural coding strategies for this higher order cognitive task.

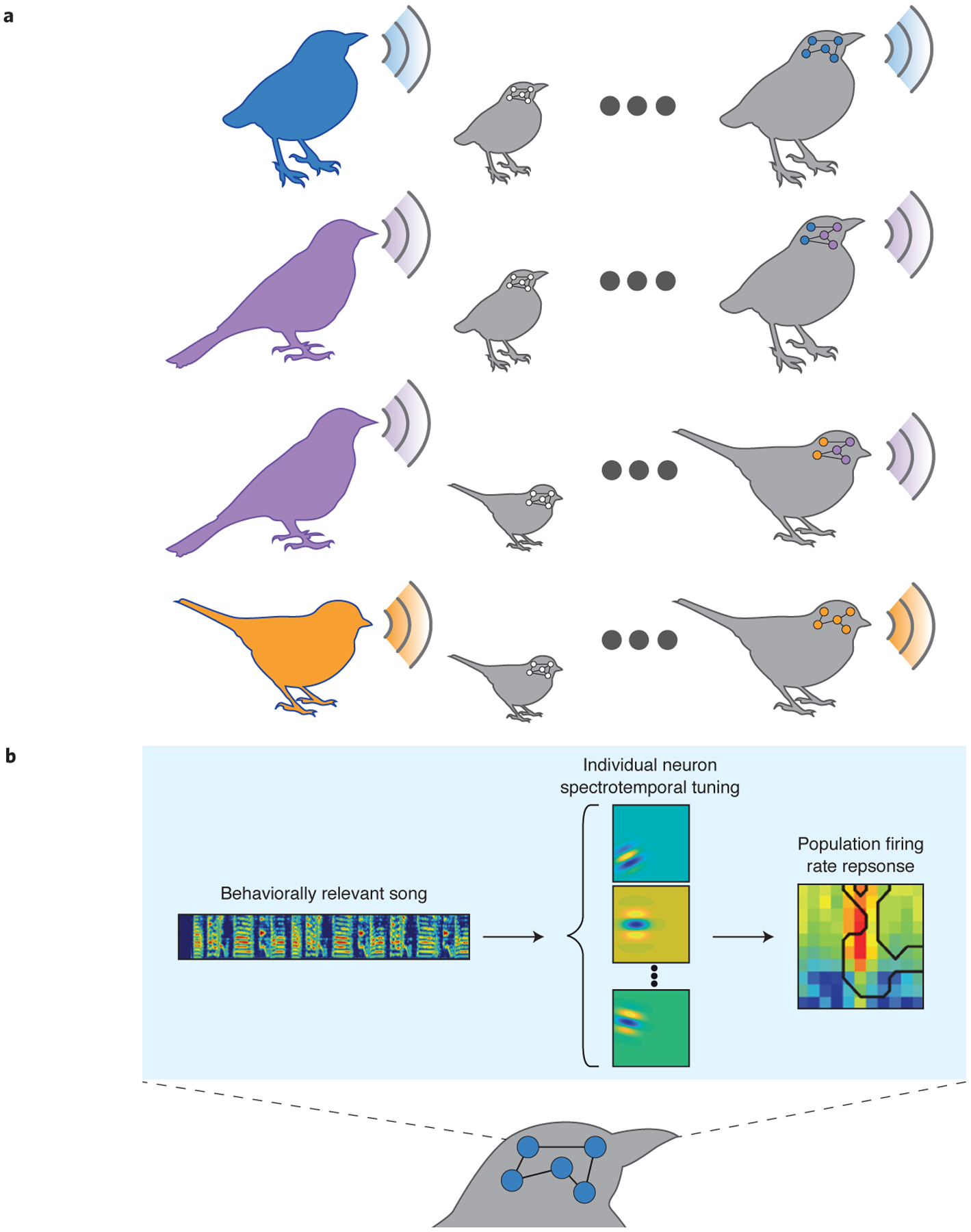

Figure 1.

Learning the bird’s song drives changes in the auditory cortex. A. Finches of two species (zebra finches or long-tailed finches) were raised by either con-specific or heterospecific tutors (Bengalese finches) and learned the tutor’s song regardless of whether the tutor was conspecific or heterospecific. Neurons in the auditory cortex developed specialization for the song of the tutor. B. The responses of neurons exhibit selectivity for the spectro-temporal structure of the tutor song, which may arise through tuning of spectro-temporal receptive fields of the neurons.

References

- 1.Werker JF & Tees RC Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior & Development 7, 49–63 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesgarani N, Cheung C, Johnson K & Chang EF Phonetic Feature Encoding in Human Superior Temporal Gyrus. Science (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gervain J & Geffen MN Efficient Neural Coding in Auditory and Speech Perception. Trends Neurosci 42, 56–65 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore JS & Woolley SMN Emergent tuning for learned vocalizations in the auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci, https://dx.doi.org/xxx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tchernichovski O, Lints T, Mitra PP & Nottebohm F Vocal imitation in zebra finches is inversely related to model abundance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 12901–12904 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Immelmann K Song development in the zebra finch and other Estrildid finches, in Bird vocalizations. (ed. Hinde RA) 61–74 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Merzenich MM, Beitel R & Schreiner CE Representation of a species-specific vocalization in the primary auditory cortex of the common marmoset: temporal and spectral characteristics. J Neurophysiol 74, 2685–2706 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrodin C, Kayser C, Logothetis NK & Petkov CI Voice cells in the primate temporal lobe. Curr Biol 21, 1408–1415 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnupp JW, Hall TM, Kokelaar RF & Ahmed B Plasticity of temporal pattern codes for vocalization stimuli in primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci 26, 4785–4795 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atencio C, Sharpee T & Schreiner C Hierarchical computation in the canonical auditory cortical circuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 21894–21899 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese A & Woolley SM Coding principles of the canonical cortical microcircuit in the avian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 3517–3522 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carruthers IM, Natan RG & Geffen MN Encoding of ultrasonic vocalizations in the auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 109, 1912–1927 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woolley S, Fremouw T, Hsu A & Theunissen F Tuning for spectro-temporal modulations as a mechanism for auditory discrimination of natural sounds. Nat Neurosci 8, 1371–1379 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanes DH & Woolley SM A behavioral framework to guide research on central auditory development and plasticity. Neuron 72, 912–929 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]