Abstract

Gout is a common arthritis caused by monosodium urate crystals. The heritability of serum urate levels is estimated to be 30–70%; however, common genetic variants account for only 7.9% of the variance in serum urate levels. This discrepancy is an example of “missing heritability.” The “missing heritability” suggests that variants associated with uric acid levels are yet to be found. By using genomic sequences of the ToMMo cohort, we identified rare variants of the SLC22A12 gene that affect the urate transport activity of URAT1. URAT1 is a transporter protein encoded by the SLC22A12 gene. We grouped the participants with variants affecting urate uptake by URAT1 and analyzed the variance of serum urate levels. The results showed that the heritability explained by the SLC22A12 variants of men and women exceeds 10%, suggesting that rare variants underlie a substantial portion of the “missing heritability” of serum urate levels.

Keywords: serum uric acids, heritability, rare variants, transporter, metabolic syndrome, genetic factors, environmental factors, cohort study

GOUT is one of the most common types of inflammatory arthritis caused by hyperuricemia. The balance between production of urate and urate excretion pathways determines an individual’s serum urate levels (Dalbeth et al. 2016). This balance can be modified by both genetic and environmental factors. Heritability estimates of serum urate span a range of 30–70% (Whitfield and Martin 1983; Emmerson et al. 1992; Yang et al. 2005; Nath et al. 2007; Vitart et al. 2008; MacCluer et al. 2010; Krishnan et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2018).

Serum urate significantly associates with 30 separate genetic loci as reported by a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of >16,000 European individuals (Köttgen et al. 2013). A weighted serum-urate genetic risk score constructed by using these variants accounted for 7.9% of the variance (Major et al. 2018b). Recently, Nakatochi et al. (2019) estimated the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based heritability (denoted h2SNP) of serum urate level in a Japanese meta-analysis and in European individuals (Köttgen et al. 2013) by using linkage disequilibrium (LD) score regression (Bulik-Sullivan et al. 2015). The heritability estimates were calculated from summary statistics of 1,447,573 SNPs, which were assessed in both studies, and have minor allele frequencies ≥1% in both studies. The h2SNP ± sampling error (SE) estimates were 14.0% ± 4.3% for the Japanese study and 14.4% ± 3.9% for the European study. In other words, the estimated proportion of the variance explained by genome-wide significant SNPs discovered by GWAS (denoted h2GWA ) and by LD score regression was only a fraction of the heritability estimated by family or twin studies. This is known as the “missing heritability” problem (Manolio et al. 2009). Missing heritability of serum urate levels indicates that as yet undiscovered variants might contribute to the phenotypic variations.

We hypothesized that rare functional SNPs are contributors to the missing heritability of serum urate levels. A previous study showed that the minor allele frequency (MAF) distribution of damaging SNPs was shifted toward rare SNPs compared with the MAF distribution of synonymous SNPs that are not likely to be functional (Gorlov et al. 2008).

In this study, we focused on the SLC22A12 gene. This gene encodes a transporter protein known as URAT1. URAT1 has been identified as a urate-anion exchanger that affects serum urate level via urate reabsorption in human kidneys (Merriman 2015; Major et al. 2018a). It was shown that SLC22A12 mutations lower the serum urate level (Enomoto et al. 2002; Ichida et al. 2004; Iwai et al. 2004; Mancikova et al. 2016). Variants of SLC22A12 were reported in the European American, African American (Tin et al. 2018), and Czech populations (Stiburkova et al. 2013, 2015; Mancikova et al. 2016), as well as German populations of European ancestry (Graessler et al. 2006), Japanese (Ichida et al. 2004; Sakiyama et al. 2016), and Korean populations (Lee et al. 2008; Cho et al. 2015), along with a subgroup of the Roma population from five regions in three European countries (Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Spain) (Claverie-Martin et al. 2018), and Sri Lanka (Vidanapathirana et al. 2018). In this study, we searched for both common and rare variations of SLC22A12 using whole-genome sequences of cohort participants of the Tohoku Medical Megabank project (TMM) conducted in the northern part of Japan (Kuriyama et al. 2016). We identified new variants and carried out experiments to examine whether they affect the resulting protein variants. Then, we carried out a functional analysis to test whether amino acid substitutions actively change the urate transporter activity without altering protein expression or membrane translocation of URAT1. We also accounted for the loss-of-function mechanism of missense mutations in URAT1 by exon skipping.

Several studies explored the link between increased serum urate levels and various components of metabolic syndrome, such as body mass index (BMI), diabetes, and glucose levels (Cook et al. 1986; Choi et al. 2005; Choi and Ford 2008; Stibůrkova et al. 2014; Davies et al. 2015; van Bommel et al. 2017; Ouchi et al. 2018). Multivariable modeling was performed after adjusting for potential covariates: age at examination, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), BMI, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

Materials and Methods

Sample information

The URAT1 protein is coded by SLC22A12 and has an amino acid length of 553. We used the whole-genome sequences (WGS) of participants of the TMM cohort study to identify the SLC22A12 variants. The TMM project was conducted by the Tohoku University Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (ToMMo) and the Iwate Medical University Iwate Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (IMM) (Kuriyama et al. 2016). A total of 3392 candidates were selected considering the traceability of participant information, and the quality and abundance of DNA samples for SNP array genotyping and WGS analysis. All candidates were genotyped with Illumina HumanOmni2.5-8 BeadChip (Omni2.5). From the candidates, 2306 samples were selected by filtering out close relatives of individual subjects, based on mean identity-by-descent (IBD; PIHAT in PLINK version 1.07) values indicating relatedness closer than third-degree relatives.

Whole-genome sequences

Samples were handled in 96-well plates during library construction. Genomic DNA samples were diluted to a concentration of 20 ng/µl using a laboratory automation system (Biomek NXP, Beckman), and fragmented using a 96-well plate DNA sonication system (Covaris LE220, Covaris) to an average target size of 550 bp. The sheared DNA was subjected to library construction with the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free HT sample prep kit (Illumina) using a Bravo liquid-handling instrument (Agilent Technologies). Finally, the completed libraries were transferred to 1.5-ml tubes labeled with a barcode, and were then denatured or neutralized, and processed for library quality control (QC).

Library quantitation and QC were performed with quantitative MiSeq (qMiSeq) (Katsuoka et al. 2014). In this protocol, 8 or 10 µl of prepared libraries was denatured with an equal volume of 0.1 N NaOH for 5 min at room temperature and diluted with a 49-fold volume of ice-cold Illumina HT1 buffer. We pooled 50 µl of 96 denatured libraries including three control samples (those examined earlier on HiSeq). Then, 60 µl of the pooled library was diluted with 540 µl of ice-cold Illumina HT1 buffer, and analyzed with MiSeq using a 25-bp, paired-end protocol. The index ratio determined by the MiSeq sequencer was used as a relative concentration to determine the condition for the HiSeq run. Additionally, an electrophoretic analysis using the Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical) software was performed as part of the library QC.

DNA libraries were analyzed using the HiSeq 2500 sequencing system, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A TruSeq Rapid PE Cluster Kit (Illumina), and one-and-a-half TruSeq Rapid SBS Kit (200 cycles, Illumina), were used to perform a 162 bp, paired-end read in Rapid-Run Mode. Based on the qMiSeq results, the libraries were diluted to the appropriate concentrations, and used for on-board cluster generation (Illumina). We routinely checked the cluster density at the first base report, and decided whether to continue the analysis depending on the density (∼550–650 K/mm2).

The sequence reads from each sample were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37/hg19) with the decoy sequence (hs37d5). Based on previous studies (Li 2014; Nagasaki et al. 2015), Bowtie2 (version 2.1.0) with the “-X 2000” option was used for mapping. The bcftools software (ver. 0.1.17-dev) and the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK version 2.5-2) were applied to each aligned result, respectively, to call the single‐nucleotide variants (SNVs). For each sample, the read depth of each SNV position was calculated for the downstream filtering steps. Here, the read depth represents the total number of sequence reads aligned to the SNV position, with the mapping quality being ≥5. The SNVs were filtered out when read depths were extraordinarily low or high to avoid repetitive sequence of the genome. The SNVs were grouped by read depth of next generation sequencing (NGS). We then filtered out the SNV loci, in which >10% of the samples were not genotyped due to the depth filter applied in the previous step.

In total, the whole genome sequences of 2049 individuals were obtained. We call this dataset 2KJPN. See details on the website of the integrative Japanese Genome Variation Database (Yamaguchi-Kabata et al. 2015).

Filtering participants

We excluded women who had undergone ovariectomy, because serum urate levels might be affected by reproductive hormones (Mumford et al. 2013). We also excluded individuals who were taking medicines, including losartan, allopurinol, febuxostat, benzbromarone, probenecid, bucolome, and topiroxostat, which reduce urate levels.

According to the questionnaire included in the ToMMo cohort study, ∼40% of diabetes patients in the ToMMo attended hospital regularly. About 28% and 29% of the cohort reported self-management of their lifestyle, with and without the guidance of medical doctors, respectively. About 3% dropped out from diabetic care. The questionnaire did not capture information on the start and end date of medication; therefore, a qualitative evaluation of diabetes treatment was difficult in this study. Thus, we excluded subjects who were diagnosed with diabetes. Instead, we used HbA1c as a covariate of serum urate level of participants without diabetes to examine the effect of glucose levels.

Among 2049 individuals, 771 were subsequently excluded. Of these, 11 withdrew their consent to participate, 585 subjects had missing data, 48 women had undergone ovarian surgery, 75 subjects were diagnosed with diabetes, and 85 were taking urate-lowering drugs. The excluded participants overlapped. The remaining 1285 participants were investigated in this study. We analyzed samples from men and women separately.

Detecting URAT1 expression in Xenopus oocytes by immunofluorescence

The QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to introduce point mutations into the URAT1-pcDNA3.1 plasmid according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the cDNA sequences. Wild-type and mutant complementary RNAs (cRNAs) were synthesized by in vitro transcription, using a T7 mMESSAGE mMACHINE cRNA synthesis kit (Ambion).

Defolliculated Xenopus oocytes (stage IV–V) were injected with 20 ng of URAT1 cRNA, and incubated in modified Barth’s solution [88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.33 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4] containing gentamicin (50 μg/mL); oocytes were incubated at 18° for 2 or 3 days.

For immunofluorescence, cRNA-injected Xenopus oocytes were fixed with paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin blocks, and sectioned. Sections were incubated with anti-URAT1 polyclonal antibody (0.8 µg/ml, Atlas Antibodies) at 4° overnight, followed by Alexa568 at room temperature for 1 hr. Sections were examined using a confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Urate transport activity was examined after making the following amino acid substitutions in URAT1: p.Leu98Phe, p.Ala209Val, p.Ala226Val, p.Ala227Thr, p.Gln297Ter, p.Lys308Arg, p.Val469Ala, p.Gln533Lys, and p.His540Tyr. Uptake of urate (10 µM) was measured in 10 oocytes injected with wild-type or variant cRNAs.

Expression of functional URAT1 variants

Uptake experiments were performed at room temperature for 60 min in uptake buffer (96 mM sodium gluconate, 2 mM potassium gluconate, 1.8 mM calcium gluconate, 1 mM MgSO4, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 10 µM [14C]urate (Moravek) to determine URAT1 transport activity. Oocytes were washed five times with ice-cold uptake solution and solubilized with 5% SDS. Radioactivity was measured in each oocyte by scintillation counting. Urate uptake into water-injected oocytes was used as the negative control. Differences of uptake between wildtype and variants were tested by Welch two-sample t-test.

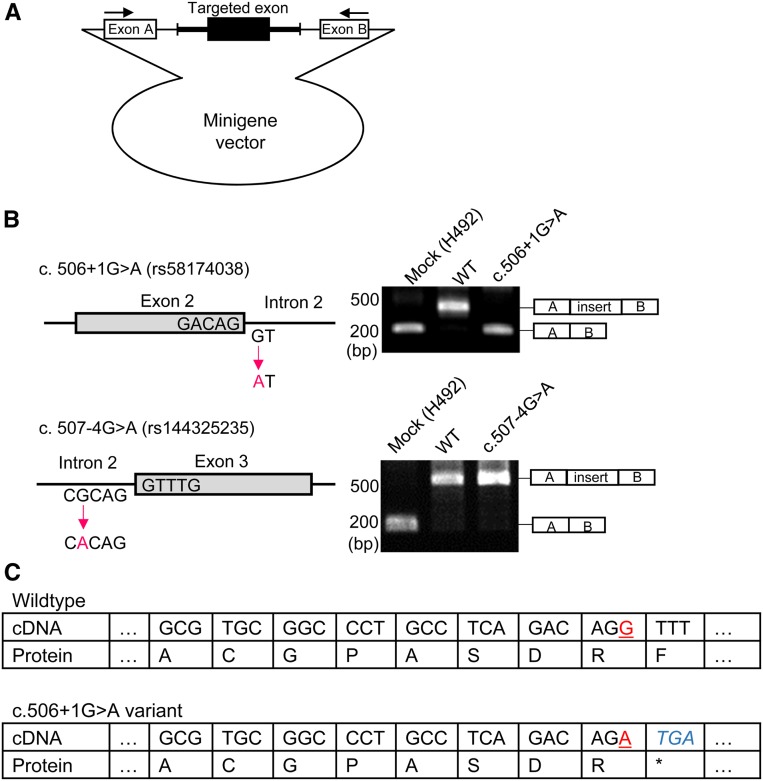

Splicing

In vitro splicing assays, using a hybrid minigene approach, were performed as described previously (Takeuchi et al. 2015). Minigene constructs were generated using the H492 vector (Habara et al. 2008). The target exons of human SLC22A12 (hSLC22A12), including ∼150 nucleotides flanking shortened introns with NheI and BamHI restriction sites, were amplified from the purchased human genome (Promega) using the following primers: forward for intron 1, 5′-aaagctagcagcctcctcctctcccatc-3′; reverse for intron 2, 5′-aaaggatccccagcaagtagggcgctttc-3′; forward for intron 2, 5′-aaagctagctgtaggtttcacccaggtgc-3′; reverse for intron 3, 5′-aaaggatccagctgaagcccagagagttc-3′. Both edges of the shortened introns were appropriately designed by the Human Splicing Finder program (http://www.umd.be/HSF/) to avoid activation of cryptic splicing. Each amplified fragment was inserted into the H492 vector, and targeted mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. For the in vitro splicing assay, HEK293T cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. After spreading the cells in six-well plates, the plasmids were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 36 hr after transfection, total cellular RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and transcribed using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo). PCR was performed using a forward primer corresponding to a segment upstream of exon A and a reverse primer complementary to a segment downstream of exon B: forward, 5′-acagctggattactcgctca-3′; reverse 5′-cagccagttaagtctctcac-3′.

Evaluation of the effect of the SLC22A12 variation on serum urate levels

Uric acid (UA) level can be modeled as the sum of genetic and environmental effects:

| (1) |

The phenotypic variance in the trait is the sum of the effects as follows:

| (2) |

In this paper, we assume the covariance of environmental and genetic factors, , to be 0. Genetic effect is the sum of additive and nonadditive genetic effects. The broad sense heritability, , is defined as

| (3) |

To examine the effects of SLC22A12 variants on serum urate levels, multivariable modeling was performed after adjusting for potential covariates: age at examination, BMI, and presence of diabetes mellitus. In this study, the environmental factors were divided into two factors:

| (4) |

By using the additivity of the variance,

| (5) |

Multivariable modeling was performed after adjusting for potential covariates: age at examination, eGFR, BMI, and HbA1c. We analyzed male and female samples separately. By using this model, the serum urate variable was adjusted to be as unaffected by environmental factors as possible:

| (6) |

By using the adjusted serum urate level, we aimed to identify additional associated genetic variants.

The difference in serum urate levels between the samples of men and women was tested by t-test. BMI is weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. These values were used in multiple regression analyses performed by the “glm” function using the statistical software R 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2018).

eGFR was calculated by the corresponding formula for each participant (Inker et al. 2012). Then, a factor of 0.908 for Japanese individuals was multiplied with the resultant values (Horio et al. 2013).

Estimation of variance explained SNPs of the SLC22A12 gene

We denoted the additive and nonadditive genetic effects as A and D, respectively.

| (7) |

Nonadditive genetic effect includes dominant, epistatic, maternal, and paternal effects. is the variance due to the additive genetic effects. The additive genetic portion of the phenotypic variance is known as narrow-sense heritability and is defined as

| (8) |

In this study, we estimated the additive genetic effect of the variants on SLC22A12 gene:

| (9) |

The additive effect of SLC22A12 variants on the variance of serum urate levels was estimated by additivity of the variance. The variance can be divided into two factors:

| (10) |

By denoting and as the variances of serum urate levels of the entire group (homozygotes of the wild-type SLC22A12) and subjects that had SLC22A12 variants, respectively, and and as the number of subjects in the wild-type SLC22A12 homozygotes and subjects that have SLC22A12 variants, respectively,

The proportion of variance explained by SNPs of SLC22A12 can be estimated as follows:

| (11) |

Burden test

We grouped the subjects according to whether or not they contained the variant that affected urate levels strongly. All included variants were assumed to be independent. Differences between mean serum urate levels in the wild-type and that of variants were compared using the t-test. This test is equivalent to a burden test (Lee et al. 2014) with the same weight for all variants.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Integration of health and genome data involves privacy violation risks. To protect privacy of the cohort participants, the TMM has established a policy of data sharing based on the policies of HIPAA, NIH, and Sanger Institute. Request for the use of the TMM biobank data for research purposes should be made by applying to the ToMMo headquarters. All requests are subject to approval by the Sample and Data Access Committee. Details are available upon request at dist@megabank.tohoku.ac.jp.

The request will be reviewed by the following criteria: (1) urgency, (2) scientific validity, (3) feasibility, (4) contribution to human health including the cohort participants, and (5) security of the requesting organization. The data are anonymized before they are provided. These criteria are shown on the TMM website:

https://www.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/tommo/qa/all-megabank.

The Sample and Data Access Committee is organized by the ToMMo and the IMM. The Sample and Data Access Committee consists of specialists from a wide variety of research fields, including human genetics, epidemiology, and jurisprudence. The chairperson and the majority of the members of the committee do not belong to Tohoku University or Iwate Medical University, which undertakes TMM projects.

The committee evaluates reidentification risks of individual datasets. When the risk is very high, the data cannot be accessed (entire genome is an example of “very high risk” data). When the risk is high, data will be shared in a specific network. When the risk is standard, the data can be transferred. Computer programs, DNA sequences, experimental protocols, and antibodies are available from the authors on request. Details are described in Takai-Igarashi et al. (2017).

Results

Variants of the SLC22A12 gene found by whole-genome sequencing

On the coding region of SLC22A12, 8 synonymous sites and 14 nonsynonymous sites segregated among 1285 participants. The rs IDs of synonymous sites are rs148378818, rs571307205, rs3825017, rs3825016, rs11231825, rs1272829728, rs7932775, and rs200072517. Nonsynonymous variations are listed in Table 1. The nonsynonymous sites consist of 11 missense sites, two stop-gain sites, and a splice site. We call SNPs that are not registered in dbSNP Build 151 novel SNPs. Novel SNPs (indicated in Table 1) show alternative allele frequency (%)found on the SLC22A12 from 1285 participants of ToMMo cohort study. Minor alleles found in this study were not found in 1000G samples, except in East Asia (Table 1). Only one individual was compound heterozygous. Table 1 shows nonsynonymous variations of SLC22A12 that were reported in previous studies in italic letters. All nonsynonymous variations except for those found in the Japanese (Ichida et al. 2004; Sakiyama et al. 2016) and Korean population (Lee et al. 2008; Cho et al. 2015) were found in 2KJPN.

Table 1. SNPs and minor allele frequency (%) that were found on the SLC22A12 from 1285 participant of ToMMo cohort study.

| Position | SNP ID | Amino acid change | Reference allele | Alternative allele | 2KJPN | 1000G | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | JPT | CHB | CHS | Other | |||||||

| 64359297 | rs121907896 | p.Arg90His | G | A | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Cho et al. (2015) | |

| Ichida et al. (2004) | ||||||||||||

| Lee et al. (2008) | ||||||||||||

| Sakiyama et al. (2016) | ||||||||||||

| 64359302 | rs144328876 | p.Arg92Cys | C | T | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Graessler et al. (2006) | |

| Mancikova et al. (2016) | ||||||||||||

| 64359320 | rs930110938 | p.Leu98Phe | C | T | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64360355 | rs58174038 | c. 506+1G | G | A | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64360873 | rs144325235 | c.507-4G > A | G | A | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64360977 | rs374743769 | p.Arg203Cys | C | T | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Mancikova et al. (2016) | |

| 64360996 | rs552232030 | p.Ala209Val | C | T | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64361020 | rs121907893 | p.Thr217Met | C | T | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Enomoto et al. (2002) | |

| 64361122 | rs145738825 | p.Ala226Val | C | T | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64361124 | rs201136391 | p.Ala227Thr | G | A | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | ||

| 64361219 | rs121907892 | p.Trp258Ter | G | A | 4.60 | 3.71 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Enomoto et al. (2002) | |

| Ichida et al. (2004) | ||||||||||||

| Lee et al. (2008) | ||||||||||||

| Sakiyama et al. (2016) | ||||||||||||

| 64366046 | Novel | p.Gln297Ter | C | T | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64366080 | Novel | p.Lys308Arg | A | G | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64366298 | rs150255373 | p.Arg325Trp | C | T | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | Tin et al. (2018) | |

| 64367290 | rs563239942 | p.Arg405Cys | C | T | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | Tin et al. (2018) | |

| 64367322 | p.Leu415_Gly417del | GGCAGGGCT | G | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Claverie-Martin et al. (2018) | ||

| 64368212 | rs200104135 | p.Thr467Met | C | T | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | Claverie-Martin et al. (2018) | |

| Tin et al. (2018) | ||||||||||||

| Vidanapathirana et al. (2018) | ||||||||||||

| 64368218 | Novel | p.Val469Ala | T | C | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64368239 | rs148862453 | p.Ala476Asp | C | A | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Claverie-Martin et al. (2018) | |

| 64368242 | rs773677616 | p.Arg477His | G | A | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Iwai et al. (2004) | |

| Stiburkova et al. (2013) | ||||||||||||

| Stiburkova et al. (2013) | ||||||||||||

| 64368409 | rs1382724038 | p.Gln533Lys | C | A | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 64368968 | rs528619562 | p.Lys536Thr | A | C | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | Tin et al. (2018) | |

| 64368979 | Novel | p.His540Tyr | C | T | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

Amino acid changes are based on ENST00000377574.

The structure of URAT1 and amino acid changes of URAT1 are shown in Figure 1. Amino acid sequences are based on ENST00000377574. MAF of 2KJPN, JPT, CHB, CHS, and other populations in the 1000G project are shown in Table 1. The effects of four sites among 11 missense variants and two stop-gain variants have already been investigated (Enomoto et al. 2002; Ichida et al. 2004; Iwai et al. 2004). Thus, we assessed urate uptake by eight nonsynonymous variants. We also investigated one splice site variant.

Figure 1.

Topology of URAT1 encoded by SLC22A12 with positions of nonsynonymous variants indicated. Amino acid changes with strong effects on urate uptake are indicated by red boxes.

URAT1 expression in Xenopus oocyte detected by immunofluorescence

Subcellular localization in oocytes of the wild-type or variant URAT1 was detected by immunostaining with a specific antibody raised against the fourth extracellular loop flanked by transmembrane domains 7 and 8 of URAT1 (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows subcellular localization of the wild type and mutants in oocytes. Immunodetection with a specific antibody raised against the C terminus of URAT1 showed that the wild-type, p.Leu98Phe, p.Ala209Val, p.Ala226Val, p.Ala227Thr, p.Lys308Arg, p.Val469Ala, p.Gln533Lys, and p.His540Tyr proteins are expressed at the plasma membrane. On the contrary, fluorescence levels were undetectable in oocytes injected with water or those injected with p.Gln297Ter cRNA.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of the URAT1 of the wildtype and variants of the SLC22A12 cRNA in Xenopus oocytes. Bar, 100 µm. The URAT1 proteins except those injected p.Gln297Ter and p.Gln297Ter complementary RNA (cRNA) are expressed at the plasma membrane, whereas fluorescence levels were undetectable in oocytes injected with water or those injected with p.Gln297Ter, p.Gln297Ter complementary RNA (cRNA).

Effects of amino acid substitution on urate uptake by URAT1

Table 2 shows the effects of amino acid substitution on urate uptake by URAT1. p.Leu98Phe, p.Lys308Arg, p.Val469Ala, or p.Gln533Lys did not decrease urate uptake. However, p.Ala209Val, p.Ala226Val, p.Ala227Thr, p.Gln297Ter, or p.His540Tyr significantly reduced urate uptake (Welch two-sample t-test, P < 0.01). By using Xenopus oocytes, previous studies have shown that p.Arg90His, p.Thr217Met, p.Trp258Ter, or p.Arg477His affect serum urate levels (Enomoto et al. 2002; Ichida et al. 2004; Iwai et al. 2004); thus, nine variants were examined in this study. Amino acid changes with strong effects on urate uptake are indicated by red boxes in Figure 1.

Table 2. Effects of amino acid substitution on urate uptake by URAT1 (pmol/oocyte/hour).

| SNP ID | Amino acid change | Mean | SE | P | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype | No Change | 8.202 | 0.412 | 1.00 | |

| rs930110938 | p.Leu98Phe | 8.275 | 0.205 | 0.88 | |

| rs552232030 | p.Ala209Val | 0.215 | 0.073 | 0.00 | a |

| rs145738825 | p.Ala226Val | 5.659 | 0.181 | 0.00 | a |

| rs201136391 | p.Ala227Thr | 3.830 | 0.291 | 0.00 | a |

| chr11:64366046 | p.Gln297Ter | 0.115 | 0.058 | 0.00 | a |

| chr11:64366080 | p.Lys308Arg | 8.960 | 0.469 | 0.24 | |

| chr11:64368218 | p.Val469Ala | 8.720 | 0.654 | 0.51 | |

| rs1382724038 | p.Gln533Lys | 7.898 | 0.298 | 0.56 | |

| chr11:64368979 | p.His540Tyr | 0.175 | 0.039 | 0.00 | a |

| Negative control | Water | 0.075 | 0.027 | 0.00 | a |

Amino acid changes are based on ENST00000377574.

Urate uptake is significantly lower than wildtype.

Effect of variation on splicing

We also found two variants close to the exon–intron boundary, rs58174038 (c. 506+1G > A) and rs144325235 (c. 507-4G > A), located on the junction between exon 2 and intron 2, and intron 2 and exon 3 of SLC22A12, respectively (Figure 1). Because variants in exon–intron boundaries can affect the splicing location, and result in abnormal transcripts by aberrant exon skipping (Takeuchi et al. 2015), we evaluated the influence of these two variants on the splicing pattern of the transcripts by in vitro splicing assay using a hybrid minigene (Figure 3A). The assay showed that the c. 506+1G > A variant caused aberrant exon skipping to exclude exon 2 (Figure 3B). In contrast, the c. 507-4G > A variant did not affect the splicing pattern. These data suggest that rs58174038 (c. 506+1G > A) causes aberrant splicing, while rs144325235 does not. Figure 3C shows the genomic sequences around rs58174038. The sequence indicates that the splice variant c. 506+1G > A presumably has a stop codon that would cause loss of function of URAT1. This site is also indicated by a red box in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Effects of variant mutations on splicing. (A) Diagram of the minigene. (B) Effect of variants on splicing. rs58174038 (c. 506+1G > A) caused aberrant splicing, whereas rs144325235 did not affect splicing. (C) Putative effect of the splice-site variation rs58174038 (c. 506+1G > A) of the SLC22A12 gene on URAT1. Two alleles of rs58174038 are indicated by underlined red letters. Genomic sequences are indicated by italic blue letters. This figure indicates that A allele will cause loss-of-function of URAT1 because of the stop codon TGA located in the genomic sequence.

Evaluation of the effect of SLC22A12 variation on serum urate levels

Table 3 summarizes the serum urate levels and characteristics of other covariates of the study subjects. The serum urate levels are reported in mg/dl in Table 3 to compare the serum urate levels with previous studies (Krishnan et al. 2012; Major et al. 2018b). These values can be converted to μmol/l if multiplied by 59.48 (Panoulas et al. 2008). The average serum urate level of the samples obtained from men was 6.07 mg/dl, which differed significantly from that of the samples obtained from women, which was 4.57 mg/dl (t-test, P < 10−22). Table 3 also summarizes mean values and SD for age, eGFR, BMI, and HbA1c levels of the subjects, and presents the linear-regression results. The eGFR levels explain about 10% of the variance in serum urate level. The effects of BMI or HbA1c were much smaller than that of eGFR.

Table 3. Characteristics of the study subjects (n = 1,285) and linear regression on serum uric acid and covariates.

| Variable | Mean | SD | β | SE | P | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 631) | ||||||

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.07 | 1.31 | ||||

| Age (year) | 61.61 | 11.23 | 0.0319 | 0.0053 | 2.29×10−9 | a |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.31 | 3.17 | 0.0635 | 0.0150 | 4.27×10−5 | a |

| eGFR (mL/minute/1.73m2) | 90.77 | 13.65 | −0.0368 | 0.0043 | 2.00×10−16 | a |

| HbA1c | 5.46 | 0.71 | −0.2289 | 0.0690 | 0.000957 | a |

| Women (n = 647) | ||||||

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 4.57 | 0.96 | ||||

| Age (year) | 57.26 | 13.17 | −0.0192 | 0.0038 | 5.99×10−7 | a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.08 | 3.65 | 0.0592 | 0.0099 | 3.12×10−9 | a |

| eGFR (mL/minute/1.73m2) | 96.09 | 14.39 | −0.0297 | 0.0034 | 2.00×10−16 | a |

| HbA1c | 5.34 | 0.36 | 0.2652 | 0.1067 | 0.0132 | |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation; SE, sampling error.

Significantly correlated.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of adjusted serum urate levels. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test did not reject normality. We grouped the participants with variations indicated by red boxes in Figure 1. In Figure 4, black boxes indicate participants with variants. It is worth noting that variations indicated by red boxes in Figure 1 are damaging urate reabsorption, so that serum urate levels of individuals with variants of the SLC22A12 gene are lower than those with wild type. Table 4 summarizes the differences in adjusted serum urate levels in participants with variations indicated by red boxes in Figure 1 and wild-type carriers. The difference was significant (t-test, P < 10−16).

Figure 4.

Distributions of adjusted serum urate levels. The X-axis indicates the serum urate level, while the Y-axis represents the participants’ number. Gray boxes represent those with the wild-type URAT1; closed boxes represent those with variants.

Table 4. The difference in adjusted serum uric acid level between carriers of variants and that of wildtype.

| Number of participants | Mean | SD | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| All | 634 | 0.00 | 1.25 | |

| Variants | 38 | −1.92 | 0.87 | < 10−16 |

| WT | 596 | 0.12 | 1.25 | |

| Women | ||||

| All | 651 | 0.00 | 0.89 | |

| Variants | 34 | −1.34 | 0.66 | < 10−16 |

| WT | 617 | 0.07 | 0.62 | |

Significantly different from adjusted serum urate level of wild-type carriers (t-test, P < 10−16).

Table 5 presents a summary of variances explained by environmental and genetic factors. The number of participants with variations indicated by red boxes in Figure 1 is also shown in Table 5. The variances are shown in (mg/dl)2. These values can be converted to (μmol/l)2 if multiplied by (59.48)2. By using the SD presented in Table 4, the variances of serum urate levels could be explained by SLC22A12 variants, which were 0.23 and 0.10 for men and women, respectively. Thus, h2URAT1 was 13.3% and 10.5% for men and women, respectively (Table 5). Table 5 also shows that age at examination, eGFR, BMI, and HbA1c explain about 10% of serum urate levels.

Table 5. Summary of variances explained by environmental and genetic factors.

| Variances | Portion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | ||

| V (U) | 1.73 | 100 |

| V (E known factors) | 0.16 | 9.4 |

| V (A SLC22A12) | 0.23 | 13.3 |

| Women | ||

| V (U) | 0.92 | 100 |

| V (E known factors) | 0.13 | 13.7 |

| V (A SLC22A12) | 0.10 | 10.5 |

V (E known factors), Variance explained by known environmental factors; V (A SLC22A12), Additive variance explained by genetic variations of the. SLC22A12 gene.

Discussion

To discover genetic variants that explain the missing heritability of serum urate levels, we examined the SLC22A12 variation in the ToMMo cohort. As a result, we detected 13 nonsynonymous sites segregated among 1285 participants (Table 1). Among these sites, previous studies have shown that four nonsynonymous sites affect urate uptake by URAT1, which is encoded by SLC22A12. We assessed urate uptake by nine variants, and showed that four variants sharply reduced the URAT1 function (Figure 1 and Table 2). We also conducted minigene experiments and found that one variation caused abnormal splicing in the SLC22A12 transcript (Figure 3). We grouped the participants with variants that affected urate uptake by URAT1, and analyzed variance in serum urate levels. The results showed that the h2URAT1 values for men and women are >10%, suggesting that rare variants underlie a substantial portion of the “missing heritability” of serum urate levels (Table 5).

Urate-uptake experiments showed that the effects of amino acid substitutions on protein function depended on substitution location in the protein primary structure (Figure 1 and Table 2). p.Gln297Ter, p.Trp258Ter, and slice-site variant truncated proteins presumably have a stop codon that would cause loss of function of URAT1. Substitutions in the transmembrane domain, p.Ala209Val, p.Thr217Met, p.Ala226Val, and p.Ala227Thr strongly affect the transporter activity of URAT1. On the other hand, the missense variations on the extracellular loops of the URAT1 protein, p.Lys308Arg, p.Val469Ala, and p.Arg477His have smaller effects on the transporter activity of URAT1 than do other variants. Substitution experiments showed that the effect of p.Ala209Val was significantly stronger than that of p.Ala226Val (P = 3.52 × 10−12; Welch two sample t-test), although both substitutions featured Ala–Val exchange. These findings provide new insights into the URAT1 structure–function relationships. Tin et al. (2018) showed that a higher CADD Phred score (Rentzsch et al. 2019) was associated with substantial adverse effects on serum urate among variants. In this study, we did not find any significant relationship between CADD Phred score and functional change of URAT1, likely because of a small number of loci (data not shown).

Although urate levels are known to be affected by various environmental factors (Major et al. 2018b), Table 3 indicates that serum urate levels are influenced primarily by eGFR. UA is freely filtered at the glomerulus, with the majority undergoing reabsorption via proximal tubular urate transporter proteins, and about one-tenth being secreted back into the filtrate in the late proximal tubules (Tasic et al. 2011; Iseki et al. 2013). Our results support the importance of kidney function in regulating serum urate levels.

Purine metabolic disorders, such as a reduced activity of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase and overactivity of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase, are associated with serum urate level (Nyhan 2005). However, patients suffering from purine metabolic disorders associated with pathological concentrations of serum uric acid (SUA) were not excluded, because the questionnaire to check for metabolic disorders of purine was not presented to cohort participants.

Table 2 also indicates that serum urate levels are also influenced by glucose level. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that SUA levels decrease in diabetes patients who have received an inhibitor of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) (Davies et al. 2015; van Bommel et al. 2017; Ouchi et al. 2018). A previous cohort study showed that serum urate levels increased with moderately increased levels of HbA1c, and then decreased as levels of HbA1c increased further (a U-shaped relationship) (Cook et al. 1986; Choi and Ford 2008). Therefore, a nonlinear model might be necessary.

A previous study showed that BMI was significantly associated with serum urate levels, even after adjusting for genetic, family, and environmental factors in both men and women (Tanaka et al. 2015). Serum urate levels in men are known to be much higher than those in women (Fang and Alderman 2000). The multivariate analyses in this study were consistent with the previous findings.

The variance of the adjusted urate levels includes the variances driven by unadjusted environmental factors, such as diet. Diet has been identified as a risk factor for the development of gout (Tsai et al. 2012; Dalbeth et al. 2016). Higher levels of meat and seafood consumption are associated with higher levels of SUA (Choi et al. 2005). Coffee consumption is associated with lower SUA level (Choi and Curhan 2007). A recent study (Major et al. 2018b) showed that diet explains minimal variation in serum urate levels in the general population. In this study, we did not incorporate the effect of food and drinks on the serum urate level, because the answers from the participants of the TMM cohort study have missing data. In future, diet effects on serum uric level will be incorporated.

Our results suggest that rare functional SNPs are major contributors to missing heritability. Including rare SNPs in genotyping platforms will advance identification of causal SNPs (Gorlov et al. 2008). Minor alleles found in this study were not found in 1000G samples, except in East Asia (Table 1). The rare variants of SLC22A12 have strong ethnic specificity. In addition, there must be rare variants of many genes other than the SLC22A12 gene that affect SUA. Rare variants on ABCG2 were identified in a Czech population (Stiburkova et al. 2017). In addition to common and rare variants, epigenetic factors are expected to explain the “missing heritability” (Manolio et al. 2009; Eichler et al. 2010), and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of TMM cohort samples is ongoing (Hachiya et al. 2017).

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Statements

The TMM project was launched in 2011 to investigate the adverse effects of the Great East Japan Earthquake in the Miyagi and Iwate prefectures (northeastern Japan) on health and well being (Kuriyama et al. 2016). Our study was approved by both the ethics committees, ToMMo and IMM (No. 2016-1018). All of the cohort participants gave written consent. In accordance with participants’ informed consent, whole-genome data were securely controlled under the Materials and Information Distribution Review Committee of TMM project, and data sharing with researchers was discussed by the review committee for each research proposal.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the volunteers who participated in this Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (ToMMo) project. We would like to thank members of ToMMo at Tohoku University for their seminal contribution to establishing the genome cohort and biobank, and help with genome analyses. The list of members of ToMMo at Tohoku University is available on the following website, https://www.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/english/a191201/. We would also like to thank the members of Iwate Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization at Iwate Medical University. We thank Ms. Noriko Ohshima for her technical assistance. We also thank Mr. Toshiya Hatanaka for drawing the figure of URAT1. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant number JP17K08682 and Tohoku Medical Megabank Project (Special Account for reconstruction from the Great East Japan Earthquake), Grant Number JP19km0105001, JP15km0105002. All computational resources were provided by the ToMMo supercomputer system (http://sc.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/en).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: E. Hauser

Literature Cited

- Bulik-Sullivan B. K., Loh P. R., Finucane H. K., Ripke S., Yang J. et al. , 2015. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47: 291–295. 10.1038/ng.3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. K., Kim S., Chung J. Y., and Jee S. H., 2015. Discovery of URAT1 SNPs and association between serum uric acid levels and URAT1. BMJ Open 5: e009360 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. K., and Curhan G., 2007. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and serum uric acid level: the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum. 57: 816–821. 10.1002/art.22762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. K., and Ford E. S., 2008. Haemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, serum C-peptide and insulin resistance in relation to serum uric acid levels–the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 713–717. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. K., Liu S., and Curhan G., 2005. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 52: 283–289. 10.1002/art.20761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie-Martin F., Trujillo-Suarez J., Gonzalez-Acosta H., Aparicio C., Justa Roldan M. L. et al. , 2018. URAT1 and GLUT9 mutations in Spanish patients with renal hypouricemia. Clin. Chim. Acta 481: 83–89. 10.1016/j.cca.2018.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G., Thelle D. S., and Whitehead T. P., 1986. Serum uric acid, serum glucose and diabetes: relationships in a population study. Postgrad. Med. J. 62: 1001–1006. 10.1136/pgmj.62.733.1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbeth N., Merriman T. R., and Stamp L. K., 2016. Gout. The Lancet 388: 2039–2052. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Trujillo A., Vijapurkar U., Damaraju C. V., and Meininger G., 2015. Effect of canagliflozin on serum uric acid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 17: 426–429 (erratum: Diabetes Obes. Metab. 17: 708). 10.1111/dom.12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler E. E., Flint J., Gibson G., Kong A., Leal S. M. et al. , 2010. Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11: 446–450. 10.1038/nrg2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson B. T., Nagel S. L., Duffy D. L., and Martin N. G., 1992. Genetic control of the renal clearance of urate: a study of twins. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51: 375–377. 10.1136/ard.51.3.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto A., Kimura H., Chairoungdua A., Shigeta Y., Jutabha P. et al. , 2002. Molecular identification of a renal urate anion exchanger that regulates blood urate levels. Nature 417: 447–452. 10.1038/nature742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., and Alderman M. H., 2000. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 283: 2404–2410. 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlov I. P., Gorlova O. Y., Sunyaev S. R., Spitz M. R., and Amos C. I., 2008. Shifting paradigm of association studies: value of rare single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82: 100–112. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graessler J., Graessler A., Unger S., Kopprasch S., Tausche A. K. et al. , 2006. Association of the human urate transporter 1 with reduced renal uric acid excretion and hyperuricemia in a German Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 54: 292–300. 10.1002/art.21499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habara Y., Doshita M., Hirozawa S., Yokono Y., Yagi M. et al. , 2008. A strong exonic splicing enhancer in dystrophin exon 19 achieve proper splicing without an upstream polypyrimidine tract. J. Biochem. 143: 303–310. 10.1093/jb/mvm227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachiya T., Furukawa R., Shiwa Y., Ohmomo H., Ono K. et al. , 2017. Genome-wide identification of inter-individually variable DNA methylation sites improves the efficacy of epigenetic association studies. NPJ Genom. Med. 2: 11 10.1038/s41525-017-0016-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio M., Imai E., Yasuda Y., Watanabe T., Matsuo S. et al. , 2013. GFR estimation using standardized serum cystatin C in Japan. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 61: 197–203. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida K., Hosoyamada M., Hisatome I., Enomoto A., Hikita M. et al. , 2004. Clinical and molecular analysis of patients with renal hypouricemia in Japan-influence of URAT1 gene on urinary urate excretion. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15: 164–173. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000105320.04395.D0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inker L. A., Schmid C. H., Tighiouart H., Eckfeldt J. H., Feldman H. I. et al. , 2012. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N. Engl. J. Med. 367: 20–29 (erratum: N. Engl. J. Med. 367: 2060). 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki K., Iseki C., and Kinjo K., 2013. Changes in serum uric acid have a reciprocal effect on eGFR change: a 10-year follow-up study of community-based screening in Okinawa, Japan. Hypertens. Res. 36: 650–654. 10.1038/hr.2013.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai N., Mino Y., Hosoyamada M., Tago N., Kokubo Y. et al. , 2004. A high prevalence of renal hypouricemia caused by inactive SLC22A12 in Japanese. Kidney Int. 66: 935–944. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuoka F., Yokozawa J., Tsuda K., Ito S., Pan X. et al. , 2014. An efficient quantitation method of next-generation sequencing libraries by using MiSeq sequencer. Anal. Biochem. 466: 27–29. 10.1016/j.ab.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köttgen A., Albrecht E., Teumer A., Vitart V., Krumsiek J. et al. , 2013. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat. Genet. 45: 145–154. 10.1038/ng.2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan E., Lessov-Schlaggar C. N., Krasnow R. E., and Swan G. E., 2012. Nature versus nurture in gout: a twin study. Am. J. Med. 125: 499–504. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama S., Yaegashi N., Nagami F., Arai T., Kawaguchi Y. et al. , 2016. The tohoku medical megabank project: design and mission. J. Epidemiol. 26: 493–511. 10.2188/jea.JE20150268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Choi H. J., Lee B. H., Kang H. K., Chin H. J. et al. , 2008. Prevalence of hypouricaemia and SLC22A12 mutations in healthy Korean subjects. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 661–666. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Abecasis G. R., Boehnke M., and Lin X., 2014. Rare-variant association analysis: study designs and statistical tests. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95: 5–23. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., 2014. Toward better understanding of artifacts in variant calling from high-coverage samples. Bioinformatics 30: 2843–2851. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCluer J. W., Scavini M., Shah V. O., Cole S. A., Laston S. L. et al. , 2010. Heritability of measures of kidney disease among zuni Indians: the zuni kidney project. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 56: 289–302. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major T. J., Dalbeth N., Stahl E. A., and Merriman T. R., 2018a An update on the genetics of hyperuricaemia and gout. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 14: 341–353. 10.1038/s41584-018-0004-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major T. J., Topless R. K., Dalbeth N., and Merriman T. R., 2018b Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: meta-analysis of population based cohorts. BMJ 363: k3951 10.1136/bmj.k3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancikova A., Krylov V., Hurba O., Sebesta I., Nakamura M. et al. , 2016. Functional analysis of novel allelic variants in URAT1 and GLUT9 causing renal hypouricemia type 1 and 2. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 20: 578–584. 10.1007/s10157-015-1186-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio T. A., Collins F. S., Cox N. J., Goldstein D. B., Hindorff L. A. et al. , 2009. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461: 747–753. 10.1038/nature08494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman T. R., 2015. An update on the genetic architecture of hyperuricemia and gout. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17: 98 10.1186/s13075-015-0609-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford S. L., Dasharathy S. S., Pollack A. Z., Perkins N. J., Mattison D. R. et al. , 2013. Serum uric acid in relation to endogenous reproductive hormones during the menstrual cycle: findings from the BioCycle study. Hum. Reprod. 28: 1853–1862. 10.1093/humrep/det085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki M., Yasuda J., Katsuoka F., Nariai N., Kojima K. et al. , 2015. Rare variant discovery by deep whole-genome sequencing of 1,070 Japanese individuals. Nat. Commun. 6: 8018 10.1038/ncomms9018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatochi M., Kanai M., Nakayama A., Hishida A., Kawamura Y. et al. , 2019. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies multiple novel loci associated with serum uric acid levels in Japanese individuals. Commun Biol 2: 115 10.1038/s42003-019-0339-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath S. D., Voruganti V. S., Arar N. H., Thameem F., Lopez-Alvarenga J. C. et al. , 2007. Genome scan for determinants of serum uric acid variability. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18: 3156–3163. 10.1681/ASN.2007040426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan W. L., 2005. Disorders of purine and pyrimidine metabolism. Mol. Genet. Metab. 86: 25–33. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi M., Oba K., Kaku K., Suganami H., Yoshida A. et al. , 2018. Uric acid lowering in relation to HbA1c reductions with the SGLT2 inhibitor tofogliflozin. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 20: 1061–1065. 10.1111/dom.13170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panoulas V. F., Douglas K. M., Milionis H. J., Nightingale P., Kita M. D. et al. , 2008. Serum uric acid is independently associated with hypertension in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Hum. Hypertens. 22: 177–182. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2018 R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch P., Witten D., Cooper G. M., Shendure J., and Kircher M., 2019. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 47: D886–D894. 10.1093/nar/gky1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakiyama M., Matsuo H., Shimizu S., Nakashima H., Nakamura T. et al. , 2016. The effects of URAT1/SLC22A12 nonfunctional variants,R90H and W258X, on serum uric acid levels and gout/hyperuricemia progression. Sci. Rep. 6: 20148 10.1038/srep20148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiburkova B., Sebesta I., Ichida K., Nakamura M., Hulkova H. et al. , 2013. Novel allelic variants and evidence for a prevalent mutation in URAT1 causing renal hypouricemia: biochemical, genetics and functional analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21: 1067–1073. 10.1038/ejhg.2013.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stibůrkova B., Pavlikova M., Sokolova J., and Kozich V., 2014. Metabolic syndrome, alcohol consumption and genetic factors are associated with serum uric acid concentration. PLoS One 9: e97646 10.1371/journal.pone.0097646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiburkova B., Stekrova J., Nakamura M., and Ichida K., 2015. Hereditary renal hypouricemia type 1 and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 350: 268–271. 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiburkova B., Pavelcova K., Zavada J., Petru L., Simek P. et al. , 2017. Functional non-synonymous variants of ABCG2 and gout risk. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56: 1982–1992. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai-Igarashi T., Kinoshita K., Nagasaki M., Ogishima S., Nakamura N. et al. , 2017. Security controls in an integrated Biobank to protect privacy in data sharing: rationale and study design. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 17: 100 10.1186/s12911-017-0494-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y., Mishima E., Shima H., Akiyama Y., Suzuki C. et al. , 2015. Exonic mutations in the SLC12A3 gene cause exon skipping and premature termination in Gitelman syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26: 271–279. 10.1681/ASN.2013091013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Ogata S., Tanaka H., Omura K., Honda C. et al. , 2015. The relationship between body mass index and uric acid: a study on Japanese adult twins. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 20: 347–353. 10.1007/s12199-015-0473-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic V., Hynes A. M., Kitamura K., Cheong H. I., Lozanovski V. J. et al. , 2011. Clinical and functional characterization of URAT1 variants. PLoS One 6: e28641 10.1371/journal.pone.0028641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tin A., Li Y., Brody J. A., Nutile T., Chu A. Y. et al. , 2018. Large-scale whole-exome sequencing association studies identify rare functional variants influencing serum urate levels. Nat. Commun. 9: 4228 10.1038/s41467-018-06620-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y. T., Liu J. P., Tu Y. K., Lee M. S., Chen P. R. et al. , 2012. Relationship between dietary patterns and serum uric acid concentrations among ethnic Chinese adults in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 21: 263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bommel E. J., Muskiet M. H., Tonneijck L., Kramer M. H., Nieuwdorp M. et al. , 2017. SGLT2 inhibition in the diabetic kidney-from mechanisms to clinical outcome. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12: 700–710. 10.2215/CJN.06080616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidanapathirana D. M., Jayasena S., Jasinge E., and Stiburkova B., 2018. A heterozygous variant in the SLC22A12 gene in a Sri Lanka family associated with mild renal hypouricemia. BMC Pediatr. 18: 210 10.1186/s12887-018-1185-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitart V., Rudan I., Hayward C., Gray N. K., Floyd J. et al. , 2008. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat. Genet. 40: 437–442. 10.1038/ng.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhang D., Xu C., Wu Y., Duan H. et al. , 2018. Heritability and genome-wide association analyses of serum uric acid in middle and old-aged Chinese twins. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 9: 75 10.3389/fendo.2018.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield J. B., and Martin N. G., 1983. Inheritance and alcohol as factors influencing plasma uric acid levels. Acta Genet. Med. Gemellol. (Roma) 32: 117–126. 10.1017/S0001566000006401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Kabata Y., Nariai N., Kawai Y., Sato Y., Kojima K. et al. , 2015. iJGVD: an integrative Japanese genome variation database based on whole-genome sequencing. Hum. Genome Var. 2: 15050 10.1038/hgv.2015.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Guo C. Y., Cupples L. A., Levy D., Wilson P. W. et al. , 2005. Genome-wide search for genes affecting serum uric acid levels: the Framingham Heart Study. Metabolism 54: 1435–1441. 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Integration of health and genome data involves privacy violation risks. To protect privacy of the cohort participants, the TMM has established a policy of data sharing based on the policies of HIPAA, NIH, and Sanger Institute. Request for the use of the TMM biobank data for research purposes should be made by applying to the ToMMo headquarters. All requests are subject to approval by the Sample and Data Access Committee. Details are available upon request at dist@megabank.tohoku.ac.jp.

The request will be reviewed by the following criteria: (1) urgency, (2) scientific validity, (3) feasibility, (4) contribution to human health including the cohort participants, and (5) security of the requesting organization. The data are anonymized before they are provided. These criteria are shown on the TMM website:

https://www.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/tommo/qa/all-megabank.

The Sample and Data Access Committee is organized by the ToMMo and the IMM. The Sample and Data Access Committee consists of specialists from a wide variety of research fields, including human genetics, epidemiology, and jurisprudence. The chairperson and the majority of the members of the committee do not belong to Tohoku University or Iwate Medical University, which undertakes TMM projects.

The committee evaluates reidentification risks of individual datasets. When the risk is very high, the data cannot be accessed (entire genome is an example of “very high risk” data). When the risk is high, data will be shared in a specific network. When the risk is standard, the data can be transferred. Computer programs, DNA sequences, experimental protocols, and antibodies are available from the authors on request. Details are described in Takai-Igarashi et al. (2017).