Abstract

Background

Hyperpolarized helium 3 magnetic resonance imaging (3He MRI) is useful for investigating pulmonary physiology of pediatric asthma, but a detailed assessment of the safety profile of this agent has not been performed in children.

Objective

To evaluate the safety of 3He MRI in children and adolescents with asthma.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective observational study. 3He MRI was performed in 66 pediatric patients (mean age 12.9 years, range 8–18 years, 38 male, 28 female) between 2007 and 2017. Fifty-five patients received a single repeated examination and five received two repeated examinations. We assessed a total of 127 3He MRI exams. Heart rate, respiratory rate and pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded before, during (2 min and 5 min after gas inhalation) and 1 h after MRI. Blood pressure was obtained before and after MRI. Any subjective symptoms were also noted. Changes in vital signs were tested for significance during the exam and divided into three subject age groups (8–12 years, 13–15 years, 16–18 years) using linear mixed-effects models.

Results

There were no serious adverse events, but three minor adverse events (2.3%; headache, dizziness and mild hypoxia) were reported. We found statistically significant increases in heart rate and SpO2 after 3He MRI. The youngest age group (8–12 years) had an increased heart rate and a decreased respiratory rate at 2 min and 5 min after 3H inhalation, and an increased SpO2 post MRI.

Conclusion

The use of 3He MRI is safe in children and adolescents with asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Children, Helium, Lung, Magnetic resonance imaging, Safety

Introduction

Asthma is the most common chronic pediatric lung disease and its prevalence is increasing worldwide [1]. Pediatric asthma requires long-term management to control the disease, the medications are of high cost, making this disease a serious global health problem [2]. The CT and hyperpolarized helium 3 (3He) MRI findings have been instrumental in furthering our understanding of the unique phenotypes of pediatric asthma [3, 4]. Because the lung is predominantly air, the conventional MR signal from water protons is weak, confined largely to the pulmonary blood vessels and with limited to no signal in the lung parenchyma. Alternatively, 3He gas inhaled as a contrast agent allows for MRI to visualize the gas-filled lung volume. Additionally, 3He MRI provides information on ventilation function, including abnormal ventilation caused by obstructive disease such as asthma (Fig. 1).Therefore, 3He MRI reveals regional details of lung function related to pulmonary physiology that contributes to the understanding of chronic pediatric lung diseases including asthma [5]. In addition, neither 3He MRI nor the related hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI technique uses ionizing radiation, and both are repeatable examinations [6, 7]. Because of these favorable characteristics, hyperpolarized gas MRI ventilation methods are expected to play an important role in further asthma research [3, 8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Breath-hold MR images of the lungs. a, b Single coronal slices from a 2-D lung volume. Conventional T1-weighted image in a 23-year-old woman shows lungs as dark non-signal area (a); after inhalation of hyperpolarized 3He, MR of the same woman shows lungs without disease, with bright homogeneous 3He gas signal distributed throughout the lung airspace (b). c For comparison, a breath-hold hyperpolarized 3He MR of a 22-year-old man with asthma shows typical inhomogeneous 3He signal caused by regional airway obstruction

The safety of 3He MRI in adults with or without lung disease has been shown to be very good, with only a small amount of oxygen desaturation that recovers within a few minutes [10–14]. This desaturation occurs because there is no oxygen in the inhaled test gas for the single breath-hold of the hyperpolarized gas MRI ventilation exam. In previous studies using 3He MRI for children with or without disease, no serious adverse events were reported [5, 9, 11, 15–21]. Based on this empirical evidence, 3He MRI appears to be safe in children. However, no report has detailed the influence of 3He MRI on vital signs and the effects of repeated exams specifically in pediatric subjects. Reference ranges of vital signs such as heart rate and respiratory rate, which provide the physiological status, differ by age in children [22]. The detailed analysis of vital changes in the different age groups by 3He MRI can be used to assess the safety of these exams for children. We hypothesized that in children and adolescents with asthma who underwent 3He MRI, any physiological effects would be transient and there would be no lasting effects. The purpose of this analysis was to determine the safety of 3He MRI in pediatric patients with asthma.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational study was approved by our institutional review board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. We obtained written parental informed consent and verbal assent from each patient.

Study population

Subjects studied in this work were drawn from two major studies: the Childhood Origins of ASThma (COAST) birth cohort and the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) multi-center longitudinal study of severe asthma. All participants have been included in previous reports [4, 5, 9, 23]. These prior articles focused on MRI biomarkers of pediatric asthma [5] and the clinical features of exacerbation-prone asthma [23], whereas in this manuscript we report on the safety of 3He MRI in pediatric asthma.

All subjects 18 years old or younger who received 3He MRI were included in our study from COAST [24] between December 2007 and October 2016 and from SARP between January 2013 and July 2017 (Fig. 2). The schedule of examination and safety assessment are shown in Fig. 3. Participants underwent prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator spirometry as described in Appendix 1. No subjects were excluded. The details of invalid and missing data are described in Appendix 2.

Fig. 2.

Enrollment flow chart for this study. No subjects were excluded. COAST Childhood Origins of ASThma, SARP Severe Asthma Research Program

Fig. 3.

Schedule of examination and safety assessment. Number of hyperpolarized 3He gas doses inhaled was two or three, depending on the patient lung volume. For Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) patients a bronchodilator was used after the first dose of 3He gas inhalation. COAST Childhood Origins of ASThma

Magnetic resonance imaging

The MRI protocols varied depending on the parent study. For COAST, the protocol was as described in the previous report [5]. The same protocol was performed at two visits, at baseline (ages 8–10 years) and post puberty (14–17 years). For SARP data included here [23], the protocol was limited to a single time point performed pre- and post-bronchodilator delivered by inhaler for patients ages 8–18 years.

After gas polarization, a 4.5-millimolar dose of hyperpolarized 3He mixed with N2 normalized to 14% of the subject’s total lung capacity was prepared in a Tedlar bag (Jensen Inert Products, Coral Springs, FL) purged of oxygen to slow T1 relaxation. The patient was positioned supine in the scanner and inhaled the gas dose from functional residual capacity through a short plastic tube attached to the bag. Subjects were instructed to hold their breath through a 7- to 20-s acquisition, and blood oxygen saturation was monitored continuously using a pulse oximeter to ensure safety during and after the anoxic breath-hold. Proton MRI was acquired to match volume and slice location after inhalation to an identical lung inflation volume. In studies of severe asthma, hyperpolarized 3He MRI was acquired before and after bronchodilation to evaluate regional response to inhaled therapy. This revealed areas of persistent obstruction after bronchodilation suggestive of airway remodeling. Briefly, for the COAST subjects, a fast 3-D whole-chest dynamic sequence was used to acquire images during gas inhalation, followed by 7- to 12-s breath-holds, and exhalation [25]. A second scan acquired diffusion-weighted data to investigate the lung microstructure and required a 15-s breath-hold [26]. For SARP subjects, a 2-D multiple slice exam was used to acquire coverage of the lung volume over an approximately 15-s breath-hold that varied slightly depending on lung size [27], and the same 2-D multiple-slice MRI was acquired before and after bronchodilator delivery. The bronchodilator was given in the upright position with the MRI study resuming after a 10-min delay to allow the drug to take effect.

Safety monitoring

Heart rate and pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation (SpO2) were continuously monitored during MRI using a pulse oximeter (Medrad Veris; Bayer Healthcare, Leverkusen, Germany). Respiratory rate was continuously monitored with a respiratory bellows gating belt (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) attached below the diaphragm during MRI. Heart rate, respiratory rate and SpO2 were recorded at four time points, including pre-MRI, 2 min and 5 min after gas inhalation, and 1 h after MRI (post MRI). Blood pressure (BP) measures were acquired using an automatic BP monitor (Medrad Veris; Bayer) pre and post MRI.

An adverse event was defined as any undesirable experience associated with the 3He MRI in a patient. A serious adverse event was defined as death or any event requiring hospitalization. Any subjective symptoms were noted before, during and 1 h after MRI. Any anxiety was evaluated subjectively by study nurses.

We defined vital signs outside of reference range for each age group (Table 1) based on previously published studies [22, 28, 29]. SpO2 less than 90% was defined as hypoxia, and SpO2 from 90% to 95% was defined as “low SpO2.” The vital signs out of reference range because of equipment error were reacquired in eight cases, and the repeat value was used for statistical analysis. These cases are tabulated in the Online Supplementary Material (Table E1).

Table 1.

Definition of vital signs out of reference range

| Age | 8–12 years old | 13–15 years old | 16–18 years old |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow heart rate | <52 | <47 | <43 |

| Fast heart rate | >115 | >108 | >104 |

| Slow respiratory rate | <14 | <12 | <11 |

| Fast respiratory rate | >25 | >23 | >22 |

| Low SpO2 | SpO2 ≤95% | ||

| Hypoxia | SpO2 <90% | ||

| High blood pressure | Systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg | ||

| Low blood pressure | Blood pressure ≥130/80 mmHg | ||

SpO2 pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation

Statistical analysis

We compared vital signs between time points within age groups using mixed-effects regression models with fixed effects for time, age group, and their interaction, and random effects for procedure nested within participant. For these results, we reported estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals. We examined the effects of potential risk factors on vital signs in two ways: by interaction testing using mixed-effect models that included time, risk factor, and time-by-risk-factor effects, and by comparing the occurrence at any time of vital signs outside the reference range by risk factor using logistic regression. Potential risk factors that we selected were as follows: age group (i.e. 8–12 years, 13–15 years, 16–18 years), gender, anxiety level, spirometry results (i.e. forced expiratory volume [FEV] percentage predicted, forced expiratory volume-one second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] percentage predicted, FEV1 reversibility), pre-MRI examination symptoms (i.e. the existence of any symptoms before MRI examination), the MRI examination following acute exacerbation of asthma, and cohort (the SARP studies used a bronchodilator intervention pre- and post-MRI, whereas COAST did not use a bronchodilator intervention; bronchodilator can increase heart rate).

Occurrences of vital signs outside of reference range were compared between time points using mixed-effects logistic regression models. We examined mixed-model regression diagnostics, including plots of leverages vs. residuals; coefficients from models re-fit excluding the highest leverage observations were compared to coefficients from the full models to assess sensitivity. We conducted analyses using R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing ) [30] including the lme4 package [31] by a statistician (author M.D.E.). A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Subject characteristics and adverse events

COAST enrolled a total of 44 children (mean 12.8 years; range 8–17 years, 25 boys, 19 girls) in this sub-study, and we included all participants in these analyses. All participants underwent 3He MRI between the ages of 8 years and 10 years. Forty-two of these children had a follow-up examination between 14 years and 17 years of age. We assessed a total of 86 exams (49 boys, mean age 12.5 years, range 8–17 years; and 37 girls, mean age 12.5 years, range 8–17 years).

SARP enrolled a total of 88 people, 22 of whom were children (mean age 13.1 years; range 8–17 years; 13 boys, 9 girls). Five of the 22 children received two repeat follow-up examinations; one was post-exacerbation follow-up, the other was 3 years after baseline. An additional 9 of the 22 children received a repeat examination 3 years later. We included in the analysis all MRI exams of patients enrolled in SARP, a total of 41 exams (24 males, mean age 13.4 years, range 8–17 years; and 17 females, mean age 12.9 years, range 8–18 years). As described later, bronchodilator was used between two MRI studies to capture pre- and post-bronchodilator images, each with inhalation of hyperpolarized 3He.

Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Two children had symptoms at the pre-MRI assessment (one cough and nasal congestion, one post nasal drainage). The vital signs of these two children were within reference range at baseline prior to the exam. Ten children (7.9%) complained of anxiety before the exam. There were no serious adverse events in this study, but there were three minor adverse events (2.3%): one subject complained of dizziness and another complained of a headache after the 3He MRI. One girl (16 years old) had multiple episodes of recorded hypoxia (SpO2 values ranged from 77% to 88%) during MRI; this was determined to be caused by malposition of the sensor. The details of all minor adverse events are presented in Appendix 3.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| Total (n=127) | COAST (n=86) | SARP (n=41) | Ages 8–12 (n=63) | Ages 13–15 (n=30) | Ages 16–18 (n=34) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.9±3.4 | 12.8±13.2 | 13.1±3.6 | 10.0±1.5 | 14.7±2.0 | 16.8±0.8 |

| Gender (F:M) | 54:73 | 37:49 | 17:24 | 28:35 | 9:21 | 17:17 |

| Pre-BD-FEV1 (% predicted) | 101.1±15.9 | 102.7±16.5 | 97.6±14.1 | 102.0±16.9 | 99.8±16.0 | 100.7±14.2 |

| Pre-BD- FEV1/FVC (% predicted) | 92.8±8.5 | 93.6±7.6 | 91.3±10.3 | 93.5±7.6 | 91.8±8.8 | 92.6±9.8 |

| FEV1 reversibility (% predicted) | 6.4±8.2 | 5.7±6.7 | 8.0±10.7 | 5.5±8.3 | 6.9±7.3 | 7.8±8.9 |

| Pre-MR exam symptoms | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anxiety | 10 (7.9%) | 8 (9%) | 2 (4.9%) | 5 (7.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | 3 (8.8%) |

BD bronchodilator, COAST Childhood Origins of ASThma, F female, FEV1 forced expiratory volume-one second, FVC forced vital capacity, M male, SARP Severe Asthma Research Program

Vital signs change

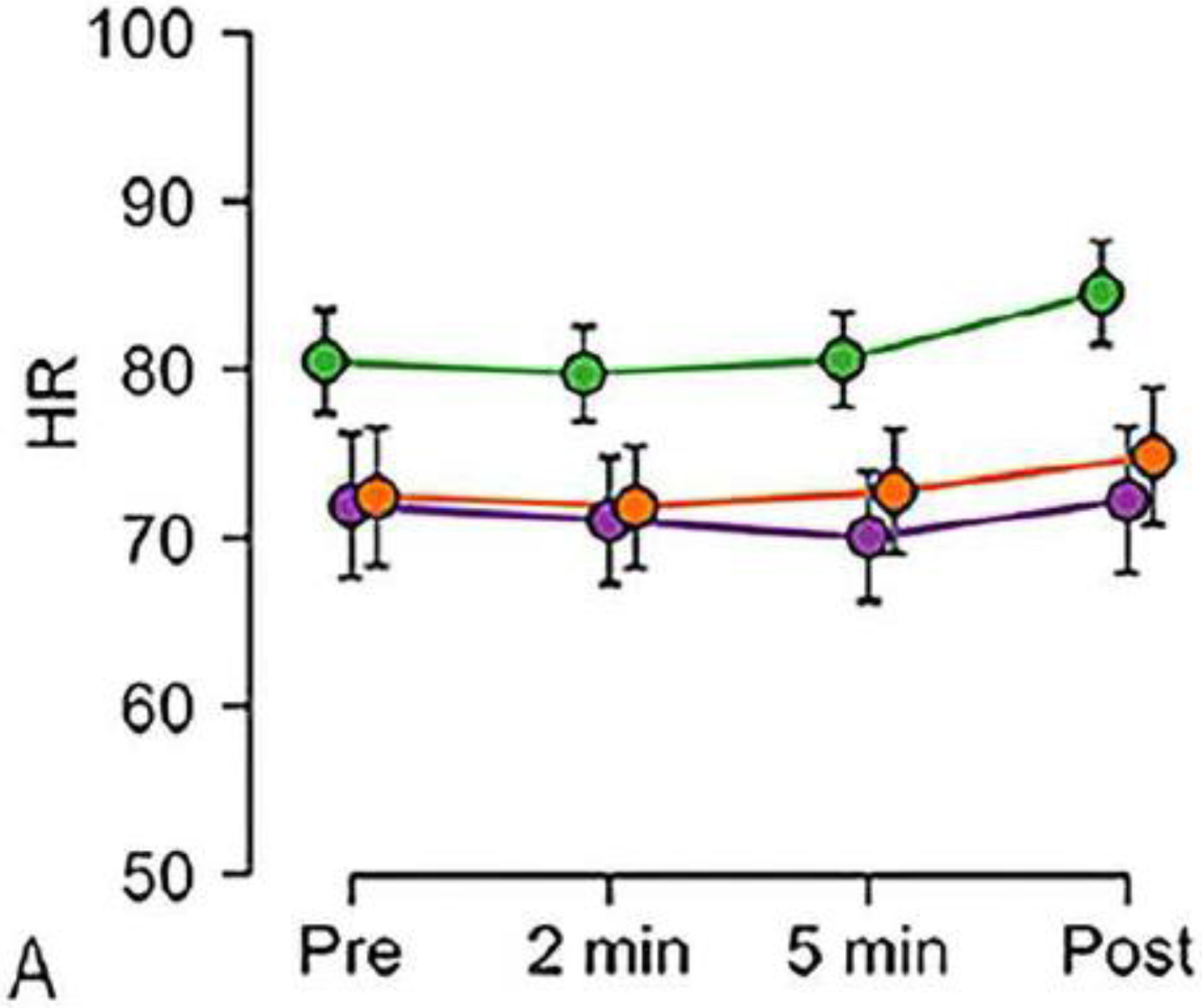

The mean change from baseline for all vital signs recorded at 2 min and 5 min after inhalation, and post MR are shown in Fig. 4 and in the Online Supplementary Material (Table E2, Figures E1–E4). Over the whole pediatric cohort, the mean (± standard deviation) increase in heart rate (2.8±0.9 beats/min, P=0.008) and increase in SpO2 (0.7±0.2%, P=0.0005) were higher post MRI than at baseline, but there were no significant changes for respiratory rate or blood pressure. For the 8- to 12-year-old group, there was an increase in heart rate post MRI (4.1±1.3 beats/min, P=0.006), a decrease in respiratory rate at 2 min (−1.3±0.4 breaths/min, P=0.009) and 5 min (−1.5±0.4 breaths/min, P=0.002) post 3H inhalation, and an increase in SpO2 post MRI (1.5±0.3%, P<0.0001; Fig. 3). In the 16- to 18-year-old group, we observed a decrease in SpO2 at 2 min after gas inhalation (−1.0±0.3%, P=0.002). The 13- to 15-year-old group showed no significant changes of any vital signs. There were no significant blood pressure changes between pre and post MRI. With inhalation of additional 3He doses, there was a small rise in heart rate (odds ratio [OR]=2.3 [1.5, 3.1], P<0.0001), a small rise in SpO2 (OR=0.38 [0.21, 0.54], P<0.0001), but no change in respiratory rate (OR=0.07 [−0.27, 0.40], P=0.70; Fig. 5). The assessment of potential risk factors for vital sign changes are detailed in the Online Supplementary Material (Tables E3 and E4).

Fig. 4.

Graphs show change in vital signs by age group (green ages 8 to 12 years; purple ages 13 to 15 years; orange ages 16 to 18 years). Data were acquired before and after children inhaled the helium dose and were averaged over all doses for a given time point. a–e Vital signs monitored include: heart rate (HR in beats/min; a), respiratory rate (RR in breaths/min; b), pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation (SpO2 %; c), systolic blood pressure (BP in mmHg; d) and diastolic blood pressure (BP in mmHg; e). The 8- to 12-year-old group (green line) shows, as expected, a higher heart rate and different patterns of change in respiratory rate and SpO2 compared to the other age groups

Fig. 5.

Graphs show change in vital signs with additional doses separated by age groups. a–c Heart rate (HR in beats/min; a), respiratory rate (RR in breaths/min; b), pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation (SpO2 percentage; c)

Vital signs outside the reference range

In seven subjects, eight measurements of vital signs fell outside the reference range (five for SpO2, two for heart rate, one for blood pressure) and were re-measured (supplemental Table E1). The frequency of vital signs outside the reference range combined over all doses is summarized in Table 3. All records of heart rate were within reference ranges. The frequency of slow respiratory rate was 4.7% (6/127) pre-MRI. The frequency of slow respiratory rate compared to pre-MRI was significantly increased at 2 min (35.4%, 45/127, P<0.0001) and 5 min (33.9%, 43/127, P<0.0001) after 3He inhalation and at post MRI (11.8%, 15/127, P=0.03). Comparison between 2 min and 5 min after 3He inhalation and post MRI showed a significant decrease of the frequency of slow respiratory rate at post-MRI assessment (P<0.0001). Fast respiratory rate of 1.6% (2/127) was seen at pre-MRI assessment, but there was no significant change of frequency at the other time points. Low SpO2 was observed in 11% of exams (14/127) at pre-MRI, and at higher frequency 2 min after inhalation (22.0%, 28/127, P=0.007). Low SpO2 was observed less frequently at post-MR assessment (4.7%, 6/127) compared to pre-MRI (P=0.04), 2 min (P<0.0001) and 5 min (18.1%, 23/127, P<0.0005) after inhalation, respectively. Blood pressure was observed above the reference range in 15% (19/127) of exams and systolic BP was below the reference range in 1.6% (2/127) of exams at pre-MRI with no significant change of frequency at post-MRI assessment. The odds ratios for vital signs out of the reference range by risk factors are detailed in the Online Supplementary Material (Table E5).

Table 3.

Frequency of vital signs outside of the reference range

| Timea | P-valueb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 2 min | 5 min | Post | Pre vs. 2 min | Pre vs. 5 min | Pre vs. pos | 2 min vs. 5 min | 2 min vs. post | 5 min vs. post | |

| 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Fast heart rate | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Slow respiratory rate | 4.7% (6/127) | 35.4% (45/127) | 33.9% (43/127) | 11.8% (15/127) | <0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.03 | 0.75 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Fast respirator y rate | 1.6% (2/127) | 2.4% (3/127) | 1.6% (2/127) | 2.4% (3/127) | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.58 |

| Low SpO2 | 11.0% (14/127) | 22.0% (28/127) | 18.1% (23/127) | 4.7% (6/127) | 0.007 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.35 | <0.000 | 0.0005 |

| Hypoxia | 0.0% | 0.8% (1/127) | 0.8% (1/127) | 0.0% | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| BP above reference range | 15.0% (19/127) | -- | -- | 15.8% (20/127) | -- | -- | 0.86 | -- | -- | -- |

| Systolic BP below reference range | 1.6% (2/127) | -- | -- | 0.8% (1/127) | -- | -- | 0.57 | -- | -- | -- |

BP blood pressure, min minutes, SpO2 pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation

For 2 min and 5 min time points, a measurement was considered outside of reference range if it was outside of reference range during any Doses 1 to 3

P-values are reported from mixed-effects logistic regression models with a fixed effect for time point and a random effect for procedure nested within participant. P<0.05 is significant (bold values)

Discussion

In this study we examined the safety of 3He MRI in children with a diagnosis of asthma or considered to be at-risk for asthma. There were no serious adverse events or clinically significant changes in physiological vital signs. However, there were occurrences of vital signs outside the reference range (low SpO2 and slow respiratory rate) during 3He MRI and change in vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, SpO2) during and after MRI. None of these changes required additional monitoring or treatment.

We found only one previous serious adverse event related to 3He MRI in the reported literature [11]. This occurred in a woman with atypical asthma who experienced uncontrolled coughing after inhalation of a second dose of 3He gas, requiring treatment [11]. The frequency of minor adverse events in adults after 3He MRI has been reported to be approximately 10% [10–12], while in this study of pediatric subjects, the adverse event rate was only found to be 2.3%. Specifically, we found three minor adverse events: dizziness, headache and records of transient hypoxia. Of note, no respiratory symptoms or cardiovascular events were observed in our pediatric asthma population.

A small increase in heart rate at post-MRI assessment, although within reference range, was seen in the 8- to 12-year-old age group. A possible reason for this is the effect of the bronchodilator, for which increasing heart rate is a common side effect when used in spirometry [32]. The post-MRI measurements were obtained in the sitting position at 1 h after MRI, but for other time points the measurements were obtained in the supine position; this difference in posture might also influence the measurements [33].

With the exception of 2 min after inhalation in the 16- to 18-year-old group, there were no significant changes in SpO2 at 2 min and 5 min after gas inhalation, generally consistent with the previous report [10]. In one previous study, the nadir of SpO2 after inhaling 3He gas was at 1 min and recovered within 2 min in patients with or without lung disease [10]. In our study, SpO2 was measured only at 2 min and 5 min after gas inhalation, such that SpO2 would be expected to recover by the first recorded measurement. It is unclear why we observed a statistically significant decrease in SpO2 at 2 min after inhalation in the 16- to 18-year-old group. One possibility is the influence of a single subject who had low recorded SpO2 between 77% to 88%, which was likely an equipment error based on clinical evaluation. However, we tested this possibility by performing a sensitivity analysis removing this subject’s data and re- running the SpO2 analyses, and found that the overall results were not changed. Without clear justification for removing this case, we chose to leave this subject’s data in the analyses.

Our results suggest younger children are more at risk for slow respiratory rate and more frequent low SpO2 after 3 He MRI. Variations in SpO2, for example, might occur because of smaller airways in this population, and the tendency of airway collapse with greater peripheral airway resistance, high compliance of the chest wall, and incomplete development of collateral ventilation in young children [34]. In addition, continuous physiological monitoring is more variable in younger age groups because of motion and inconsistent cooperation. There was significant increase in heart rate and SpO2 with additional doses; however, the change was small or within reference ranges and was not meaningful from a clinical perspective. Most of the vital signs found to fall outside the reference ranges were recorded at baseline prior to the exam. This is likely a result of pre-test anxiety, but underlying asthma or the medical treatment regimen of this study population cannot be ruled out. Regarding respiratory rate, the recorded values are not always accurate because of pauses from breath-holding and the talking required for the patient to confirm that he or she understands the instructions. Moreover, these children were instructed to rapidly inhale the 3He gas while lying supine within the constrained environment of the MRI scanner bore and radiofrequency coil, which could increase the anxiety of the procedure. We used a more conservative value for “low SpO2” than in previous studies [18, 19]; this value was defined based on new evidence [28] appropriate for children. There were several cases in which repositioning of the pulse oximetry probe at baseline led to improved SpO2 readings (Online Supplementary Material [Table E1]). Therefore, the increased frequency for low SpO2 events at 2 min could be a result of malposition of the finger pulse oximetry probe. The frequency of low SpO2 events was decreased at post-MRI assessment, which occurred face-to-face outside the MRI scanner and used a different probe. An additional factor might be the airway relaxation effect of bronchodilator in children who were studied post-bronchodilator.

This study has several limitations. First, the subject number of each age group varies, and the proportion of each gender within the age groups is unbalanced because of retrospective analysis. Second, the protocol of 3He MRI varied among cohorts (e.g., number and manner of inhaled gas doses and use of bronchodilator). Third, the posture and the equipment used in the assessment of vital signs were different at each time point and each exam. In addition, the calibration of the equipment measuring vital sings was conducted only monthly. Fourth, data for vital signs were missing at some time points; however, missing data are partly reconciled by the use of a mixed-effects model. Finally, confirmation of positioning of the pulse oximeter during the exam was sometimes difficult, lowering the reliability of absolute SpO2 values during MRI.

Conclusion

The use of 3He MRI for ventilation imaging is safe in children and adolescents with asthma. The SpO2 levels were not adversely affected by this test, although younger children tended to have a more variable respiratory rate and SpO2 than their older peers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the nurse coordinators (Jan Yakey, RN, and Molly Ellertson, RN) and research technologists — Kelly Hellenbrand, RT(R), Sara John RT(R), and Janelle Grogan RT(R) — who supported the safety monitoring, data acquisition and regulatory reporting for the MRI components for the studies in this work. Parts of this work were funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI): U10 HL109168, P01 HL070831 (COAST), R01 HL126771 (SARP), NIH/National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) Pulmonary Imaging Center S10 OD016394. This project was also supported in part by the University of Wisconsin, Department of Radiology, Research and Development Fund, and by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Spirometry

For COAST, the spirometry was performed as described in Guilbert et al. [35]. For SARP, spirometry was performed as described in Denlinger et al. [24]. Briefly, spirometry was performed according to ATS/ERS standards [36] pre- and post-bronchodilation with albuterol, and expressed as the percent of predicted values obtained from the GLI 2012 reference equations [37]. Short- and long-acting bronchodilator medications were held prior to the visits, and post-bronchodilation measurements were obtained after 2 actuations of albuterol for COAST, and after 4–8 actuations for SARP.

Appendix 2

Invalid or missing data

The timing of gas inhalation was decided by technician and there were some cases whose second or third dose was given at the same time or before the vital sign assessment at 2 minutes or 5 minutes after the previous dose. We excluded these 29 measurements in 27 exams as invalid data (Next dose was given before the 5 minute assessment; 19 measurements, Next dose was given at same time as the 5 minute assessment; 10 measurements, Next dose was given at same time as the 2 minute assessment; 1 measurement).

There were 12 cases of missing data. All missing data were at one hour after MRI (Blood pressure; 1 case, Heart rate; 1 case, Respiratory rate; 5 cases, SpO2; 5 cases).

Appendix 3

Minor adverse events

Case 1.

A 15 year old girl complained of feeling dizzy at the time point of 5 minutes after inhaling a 3rd dose of helium gas. Her vital signs were normal when she was feeling dizzy. She didn’t complain of dizziness after MR exam and was discharged asympomatic.

Case 2.

A 15 year old boy complained of headache at the post-MRI assessment. At that time, his vital signs were normal, and he did not report other symptoms like dizziness or shortness of breath. One hour after discharging, a follow-up call was made and a message was left at home. There were no further reported problems.

Case 3.

A 16 year old girl had multiple recorded measures of hypoxia. The first hypoxia record (SpO2 88%) was remeasured with repositioning of probe pulse oximetry probe and corrected to SpO2 93%, however after that, recorded measures of hypoxia continued over several minutes. Other vitals (heart rate and respiratory rate) were normal and she didn’t complain of any symptoms during this time. The SpO2 recorded at 16 minutes after the first hypoxia record was 100%. The results of spirometry on the same day of MRI were normal. This 3He MRI examination was her second exam. At the first exam 3 years prior, there were no records of hypoxia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest The authors of this manuscript declare relationships with the following companies: Mark L. Schiebler, MD, is a shareholder in Healthmyne and Stemina Biomarker Discovery; Sean B. Fain, PhD, receives grant support from GE Healthcare and serves on the scientific advisory board of Xemed.

References

- 1.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM et al. (2012) National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001–2010. Vital Health Stat 3 1–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Initiative for Asthma (2017) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/wmsGINA-2017-main-report-final_V2.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2019

- 3.Fain SB, Mummy DG, Sorkness RL (2017) Hyperpolarized gas MRI of the lung in asthma In: Hyperpolarized inert gas MRI. Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teague WG, Phillips BR, Fahy JV et al. (2018) Baseline features of the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP III) cohort: differences with age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 6:545–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadman RV, Lemanske RF, Evans MD et al. (2013) Pulmonary 3He magnetic resonance imaging of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131:369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walkup LL, Thomen RP, Akinyi TG et al. (2016) Feasibility, tolerability and safety of pediatric hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging in healthy volunteers and children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Radiol 46:1651–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niles DJ, Kruger SJ, Dardzinski BJ et al. (2013) Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: reproducibility of hyperpolarized 3He MR imaging. Radiology 266:618–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svenningsen S, Eddy RL, Lim HF et al. (2018) Sputum eosinophilia and magnetic resonance imaging ventilation heterogeneity in severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197:876–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altes TA, Mugler JP, Ruppert K et al. (2016) Clinical correlates of lung ventilation defects in asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137:789–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutey BA, Lefrak SS, Woods JC et al. (2008) Hyperpolarized 3He MR imaging: physiologic monitoring observations and safety considerations in 100 consecutive subjects. Radiology 248:655–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altes T, Gersbach J, Mata J (2007) Evaluation of the safety of hyperpolarized helium-3 gas as an inhaled contrast agent for MRI [abstr]. Proc Intl Soc Mag 15:1305 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fain SB, Korosec FR, Holmes JH et al. (2007) Functional lung imaging using hyperpolarized gas MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 25:910–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lange EE, Altes TA, Patrie JT et al. (2009) Changes in regional airflow obstruction over time in the lungs of patients with asthma: evaluation with 3He MR imaging. Radiology 250:567–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Beek EJR, Dahmen AM, Stavngaard T et al. (2009) Hyperpolarised 3He MRI versus HRCT in COPD and normal volunteers: PHIL trial. Eur Respir J 34:1311–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirby M, Parraga G (2013) Pulmonary functional imaging using hyperpolarized noble gas MRI: six years of start-up experience at a single site. Acad Radiol 20:1344–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flors L, Mugler JP, Paget-Brown A et al. (2017) Hyperpolarized helium-3 diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging detects abnormalities of lung structure in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Thorac Imaging 32:323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altes TA, Meyer CH, Mata JF et al. (2017) Hyperpolarized helium-3 magnetic resonance lung imaging of non-sedated infants and young children: a proof-of-concept study. Clin Imaging 45:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koumellis P, van Beek EJR, Woodhouse N et al. (2005) Quantitative analysis of regional airways obstruction using dynamic hyperpolarized 3He MRI — preliminary results in children with cystic fibrosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 22:420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Beek EJ, Hill C, Woodhouse N et al. (2007) Assessment of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis using hyperpolarized 3-helium MRI: comparison with Shwachman score, Chrispin-Norman score and spirometry. Eur Radiol 17:1018–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodhouse N, Wild JM, van Beek EJ et al. (2009) Assessment of hyperpolarized 3He lung MRI for regional evaluation of interventional therapy: a pilot study in pediatric cystic fibrosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 30:981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altes TA, Johnson M, Fidler M et al. (2016) Use of hyperpolarized helium-3 MRI to assess response to ivacaftor treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 16:267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming S, Thompson M, Stevens R et al. (2011) Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet 377:1011–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denlinger LC, Phillips BR, Ramratnam S et al. (2017) Inflammatory and comorbid features of patients with severe asthma and frequent exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195:302–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemanske RF Jr (2002) The Childhood Origins of Asthma (COAST) study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 13:38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes JH, Korosec FR, Du J et al. (2007) Imaging of lung ventilation and respiratory dynamics in a single ventilation cycle using hyperpolarized He-3 MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 26:630–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Halloran RL, Holmes JH, Altes TA et al. (2007) The effects of SNR on ADC measurements in diffusion-weighted hyperpolarized He-3 MRI. J Magn Reson 185:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zha W, Kruger SJ, Cadman RV et al. (2018) Regional heterogeneity of lobar ventilation in asthma using hyperpolarized helium-3 MRI. Acad Radiol 25:169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder JW, Baraff SB, Gaschler WN, Baraff LJ (2015) Pulse oxygen saturation values in a healthy school-aged population. Pediatr Emerg Care 31:645–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM et al. (2017) Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team (2019) The R project for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 15 May 2019

- 31.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cekici L, Valipour A, Kohansal R, Burghuber OC (2009) Short-term effects of inhaled salbutamol on autonomic cardiovascular control in healthy subjects: a placebo-controlled study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 67:394–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macwillim JA (1933) Postural effects of heart rate and blood pressure. Q J Exp Physiol Postural 23:1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozer M, Buyuktiryaki B, Sahiner UM et al. (2018) Repeated doses of salbutamol and aeroallergen sensitisation both increased salbutamol-induced hypoxia in children and adolescents with acute asthma. Acta Paediatr 107:647–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guilbert TW, Singh AM, Danov Z et al. (2011) Decreased lung function after preschool wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in children at risk to develop asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:532–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V et al. (2005) Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 26:319–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ et al. (2012) Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 40:1324–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.