Abstract

Background

Contraceptive education is generally a standard component of postpartum care, although the effectiveness is seldom examined. The assumptions that form the basis of such programs include postpartum women being motivated to use contraception and that they will not return to a health provider for family planning advice. Women may wish to discuss contraception both prenatally and after hospital discharge. Nonetheless, two‐thirds of postpartum women have unmet needs for contraception. In the USA, many adolescents have repeat pregnancies within a year of giving birth.

Objectives

Assess the effectiveness of educational interventions for postpartum women on contraceptive use

Search methods

We searched for trials through June 2015 in PubMed, CENTRAL, CINAHL, POPLINE, and Web of Science. For current trials, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP. Previous searches also included EMBASE and PsycInfo. We also examined reference lists of relevant articles. For earlier versions, we contacted investigators to locate additional reports.

Selection criteria

We considered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined postpartum education about contraceptive use, whether delivered to individuals or to groups of women. Studies that randomized clusters rather than individuals were eligible if the investigators accounted for the clustering in the analysis. The intervention must have started within one month after delivery.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed titles and abstracts identified during the literature searches. The data were abstracted and entered into Review Manager. Studies were examined for methodological quality. For dichotomous outcomes, the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. Where data were sFor continuous variables, we computed the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. Due to varied interventions and outcome measures, we did not conduct meta‐analysis.

Main results

Twelve trials met our eligibility criteria, included the three added in this update. The studies included a total of 4145 women. Eight trials were conducted in the USA; the others were from Australia, Nepal, Pakistan, and Syria. Four studies provided one session before hospital discharge; three had structured counseling of varying intensity and one involved informal counseling. Of eight interventions with than one contact, five focused on adolescents. Three of the five involved home visiting, one provided multiple clinic services, and one had in‐person contact and phone follow‐up. Of the remaining three for women of varying ages, two involved home visits and one provided phone follow‐up.

Our sensitivity analysis included six trials with evidence of moderate or high quality. In a study with adolescents, the group with home‐based mentoring had fewer second births within two years compared to the control group (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.00). The other five interventions had no effect. Of trials with lower quality evidence, two showed some effectiveness. In Nepal, women with an educational session immediately postpartum were more likely to use contraception at six months than those with a later or no session (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.50). In an Australian study, teenagers in a structured home‐visiting program were more likely to have effective contraception use at six months than those with standard home visits (OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.35 to 7.79).

Authors' conclusions

We focused our results summary on trials with moderate or high quality evidence. Overall, the overall quality of evidence in this review was moderate to low and the evidence of effectiveness was mostly low quality. The interventions could be improved by strengthening the program design and implementation. Some studies did not report program training for providers, adherence to the intervention protocol, or measurement of participants' knowledge and skills. Many trials did not have an objective outcome measure, i.e., pregnancy test or structured questionnaire for contraceptive use. Valid and reliable outcome measures are needed to obtain meaningful results. Still, given the associated costs and logistics, some programs would not be feasible in many settings.

Plain language summary

Education about family planning for women who have just given birth

Counseling about family planning is standard for most women who just gave birth. Few providers and researchers have looked at how well the counseling works. We do not know if postpartum women want to use family planning or whether they will return to a health provider for birth control advice. Women may wish to discuss family planning before they have the baby and after they leave the hospital. Women may also prefer to talk about birth control along with other health issues. In this review, we looked at the effects of educational programs about family planning for women who just had a baby.

Through June 2015, we searched for trials of education about family planning after having a baby. We also wrote to researchers to find other trials. The trials had to study how much the program affected family planning use. The program must have occurred within a month after the birth. We entered the data into RevMan and used the odds ratio to examine effect. We also looked at the quality of the research methods.

We found 12 trials with 4145 women. Eight studies were from the USA and the others were from Australia, Nepal, Pakistan, and Syria. Four trials provided one counseling session before hospital discharge. Of eight studies with more than one contact, five focused on teens. Three of the five had home visiting, one used clinic services, and one had personal and phone contacts. Of three studies with women and teens, two had home visits and one used phone contact.

Six trials had results of moderate quality. In a study with adolescents, the group with home‐based mentoring had fewer second births within two years compared to the control group. Of trials with lower quality evidence, two showed some effect. In Nepal, more of the women with some counseling right after delivery may use birth control at six months than those with a session later or none. In Australia, more teens in a special home‐visiting program used birth control correctly at six months than those with standard home visits.

We found moderate to low quality results overall. Most of those with some effect were low quality. Better program design and carrying out could make them stronger. Even still, some programs might cost too much for some settings.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Special education compared with routine or delayed education for contraceptive use | ||||

|

Patient or population: women with postpartum status Settings: clinic or community Intervention: special contraception education Comparison: see Comments | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Second birth (by 24 months) | OR 0.41 (95% CI 0.17 to 1.00) | Participants = 149 (Black 2006) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Home mentoring vs usual care |

| Contraception use (at 6 months): immediate session vs no immediate session | OR 1.62 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.50) | Participants = 393 (Bolam 1998) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Education: immediate vs later |

| Effective contraception use (at 6 months) | OR 3.24 (95% CI 1.35 to 7.79) | Participants = 124 (Quinlivan 2003) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Home visiting: structured vs routine |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

Background

Description of the condition

Nearly two‐thirds of women in their first postpartum year have an unmet need for family planning (Ross 2001; USAID 2014). Data from 17 countries show that return to sexual activity is associated with the return of menses, breastfeeding status, and postpartum duration but not generally associated with contraceptive use (Borda 2010). Millions of women, especially in lower‐resource areas, are at risk for unplanned pregnancy and its consequent morbidity and mortality. Even in higher‐resource areas such as the USA, nearly 60% of pregnancies are unintended, i.e., either unwanted (23%) or mistimed (37%) (Mosher 2012). First‐time adolescent mothers who do not start contraception before hospital discharge are more likely to have a repeat pregnancy within two years (Damle 2015). While adolescents may start using contraception during the postpartum period, they often discontinue due to lack of information or support (Wilson 2011).

Description of the intervention

Contraceptive education is generally considered a standard component of postpartum care. The counseling is frequently part of discharge planning but may also begin antepartum (Glasier 1996; Glazer 2011). Postpartum contraception counseling is often limited to one encounter, which is unlikely to affect behavior. Decisions about contraception made right after counseling may differ considerably from contraceptive use postpartum (Engin‐Üstün 2007; Glazer 2011). In some locations, postpartum care may be limited and undocumented, and may focus on the infant rather than the mother (Do 2013).

Postpartum women may wish to discuss contraception prenatally or after hospital discharge, preferably in the context of general education about maternal and child health (Glasier 1996; Ozvaris 1997). Many women are comfortable with advice and a prescription from their physician during well‐baby visits (Fagan 2009). In a rural area in Bangladesh, intensive provision of maternal and child health and family planning programs resulted in increased uptake of contraceptives (Koenig 1992). A recent trial examined the effect on contraceptive use from integrating family planning into infant immunization services (FHI 360 2013). However, the women were 6 to 12 months postpartum by that time.

Educational interventions provided to individuals or groups may increase contraceptive uptake as well as improve use and continuation of the chosen method. Counseling may involve a single contact or multiple sessions. Personal interaction can help women choose an appropriate method and obtain detailed information about method use. Social marketing can have greater reach and may increase awareness and promote use of contraceptives (Chapman 2012). Educational projects may also utilize technology, such as mobile phone reminders for appointments and medication use. Some programs engage peer educators or community workers to provide reminders and encourage method continuation.

Why it is important to do this review

In the past, midwifery and obstetric texts rarely questioned the effectiveness of postpartum contraceptive education, though it was considered a responsibility in postpartum care (Keith 1980; Semeraro 1996). Research evaluating such education is still sparse. More is known about the appropriateness of specific contraceptive methods for postpartum women than about how to help women use certain contraceptives (Shaw 2007). This review examines randomized controlled trials of postpartum interventions to educate women about contraceptive use. In this update we sought additional evidence on the effectiveness of such efforts.

Objectives

We assessed the effectiveness of educational interventions for postpartum women on contraceptive use.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined postpartum education about contraceptive use, whether delivered to individuals or to groups of women. Studies that randomized clusters rather than individuals were eligible if the investigators accounted for the clustering in the analysis.

Types of participants

Women gave birth at 20 weeks of gestation or more. We excluded trials focused on the needs of women with alcohol or drug problems and trials focused on women with chronic health conditions such as HIV or diabetes.

Types of interventions

Trials were included if they evaluated postpartum education provided to influence uptake of contraception including lactational amenorrhea. Educational interventions may have been based on written materials, video or audio recordings, or individual or group counseling. The intervention must have started postpartum and begun within one month of delivery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

To be included, trials had to have data on unplanned pregnancies or contraceptive choice or use. The trials may have had other primary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Additional outcomes were knowledge and attitudes about contraception and satisfaction with postnatal care.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Through June 2015, we conducted searches of MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), POPLINE, CINAHL, and Web of Science. We also searched for current trials via ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP. The search strategies are given in Appendix 1. Previous search strategies also included EMBASE and PsycINFO; they are shown in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of relevant papers were examined for additional citations. For previous versions, we also contacted investigators in the field to seek unpublished trials or published trials we may have missed in our searches.

For the initial review in 1999, the authors contacted the following organizations for advice about relevant research: Guttmacher Institute, California Family Health Council, Contraceptive Research and Development, Couple to Couple League, Engender Health, European Commission, Health, Family Planning and AIDS Unit, Family Planning Association of Queensland, Family Planning Councils of America, Family Planning International Assistance, Family Planning Management Development, Healthy Women, Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs, Marie Stopes International, National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association, Planned Parenthood Global Partners, Population and Community Development Association, Population Reference Bureau, Prime II, Program of Appropriate Technology in Health. The authors also searched databases listing publications by the Population Council, Family Health International (now FHI 360), and the World Health Organization.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One author reviewed the search results and a second author examined the reports identified for appropriate categorization. We excluded studies that randomized clusters rather than individuals and did not account for the clustering in the analysis. For the initial review, the three authors independently assessed the studies to determine which were suitable for inclusion. The authors resolved any differences by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors conducted the data extraction. One author entered the data into Review Manager (RevMan 2014), and a second author checked accuracy (Contributions of authors). These data included the study characteristics, risk of bias, and outcome data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Intervention fidelity

We used the framework in Borrelli 2011 to assess the quality of the intervention. Domains of treatment fidelity are study design, training of providers, delivery of treatment (intervention), receipt of treatment, and enactment of treatment skills. The framework was intended for assessing current trials. Criteria of interest for our review are shown below.

Study design: had a curriculum or treatment manual

Prior training of providers: specified providers' credentials

Project‐specific training: provided standardized training for the intervention

Delivery: assessed adherence to the protocol

Receipt: assessed participants' understanding and skills regarding the intervention.

In this update, we revised the terminology for the first four criteria, but the concepts are the same. We added the fifth criterion of 'Receipt' in this version of this review, based on newer information in Borrelli 2011. For the assessment of evidence quality, we downgraded the studies that met fewer than four of the five criteria.

Research design

Included trials were evaluated for methodological quality in accordance with recommended principles (Higgins 2011). Factors considered included randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, and losses to follow‐up and early discontinuation. This information was entered into the Risk of bias tables (Characteristics of included studies).

Measures of treatment effect

For the dichotomous outcomes, the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. An example is the proportion of women who initiated use of a particular contraceptive method. Fixed and random effects give the same result if no heterogeneity exists, as when a comparison includes only one study. Where data were sparse, we used the Peto OR. For continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) was computed with 95% CI. Review Manager uses the inverse variance approach.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Due to varied study designs, we were unable to conduct meta‐analysis. Therefore, we did not need to assess statistical heterogeneity. However, we address heterogeneity due to differences in interventions, study design, and populations in the Discussion.

Data synthesis

We applied principles from GRADE to assess the quality of evidence and address confidence in the effect estimates (Balshem 2011; Higgins 2011). Our assessment of the body of evidence is based on the quality of evidence from the studies. When a meta‐analysis is not viable because of varied interventions or outcome measures, a summary of findings table is not feasible. Therefore, we did not conduct a formal GRADE assessment, i.e., with an evidence profile and summary of findings table, for all outcomes (Guyatt 2011).

Our assessment of evidence quality included the design, implementation, and reporting of both the intervention and the trial. We incorporated the quality of intervention evidence into the overall assessment of evidence quality. We considered RCTs to be high quality then downgraded for the following:

intervention fidelity information for fewer than four criteria;

no information on randomization sequence generation or allocation concealment, or risk of bias was high for one;

outcome assessment lacked an objective measure, e.g., pregnancy test or structured questionnaire for contraceptive use;

follow‐up less than three months for contraceptive use or less than six months for pregnancy;

loss to follow‐up greater than 20%.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis included evidence of moderate or high quality.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The 2012 search produced 217 new references. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 212 were discarded due to not meeting the eligibility criteria. We examined the full text of five reports; two were later excluded. Three reports from two trials were added to the eight trials included in earlier versions of this review. In addition, we included two ongoing trials identified in clinical trials databases.

In 2015, searches of databases yielded 277 unduplicated citations. A total of 101 duplicates were removed electronically or by hand. With one identified from other sources, the total of unduplicated references was 278. We reviewed the full text of eight items. We included three primary reports; one was a conference abstract for which we had the ClinicalTrials.gov listing. We also included one secondary article and two abstracts related to full reports. We excluded two primary reports. From recent clinical trial listings, we obtained 40 unduplicated trials. We categorized one as ongoing and updated one listing from the earlier review.

Included studies

We included 12 trials that met our eligibility criteria after adding 3 in this update (Simmons 2013; Tang 2014; Torres 2014). The studies included a total of 4145 women; the mean was 319 and the median was 240. One trial had a preliminary report published as a conference abstract (Torres 2014).

Eight studies were conducted in the USA; the other four were from Australia (Quinlivan 2003), Nepal (Bolam 1998), Pakistan (Saeed 2008), and Syria (Bashour 2008). Six trials focused on adolescents (O'Sullivan 1992; Quinlivan 2003; Black 2006; Barnet 2009; Katz 2011) or young women (Gilliam 2004).

The studies varied in the content and format of the education provided (Table 15).

1. Intervention description.

| Study | N | Population | Country | Intervention location; medium | Intervention content |

| O'Sullivan 1992 | 243 | Adolescents | USA | Well‐baby clinic | Special well‐baby care |

| Bolam 1998 | 540 | Women | Nepal | Hospital and home | Health education, including infant care and family planning |

| Quinlivan 2003 | 139 | Adolescents | Australia | Home | Structured support and counseling |

| Gilliam 2004 | 33 | Young women (<= 25 years) | USA | Hospital | Oral contraceptive use |

| Black 2006 | 181 | Adolescents | USA | Home | Parenting (included contraception) |

| Bashour 2008 | 903 | Women | Syria | Home | Education and support, including breastfeeding and contraception |

| Saeed 2008 | 648 | Women | Pakistan | Hospital | Contraceptive use |

| Barnet 2009 | 237 | Adolescents | USA | Home; CAMI | Parenting (included contraception); case management |

| Katz 2011 | 249 | Adolescents | USA | Community; cell phone | Health risks and teen attitudes; included reproductive health planning |

| Simmons 2013 | 50 | Women | USA | Hospital; phone | LARC, logistics |

| Tang 2014 | 800 | Women | USA | Hospital; script | LARC |

| Torres 2014 | 121 | Women | USA | Hospital; script | Relative effectiveness of methods |

CAMI = computer‐assisted motivational intervention LARC = long‐acting reversible contraception

Four provided one educational session before hospital discharge, with the content focused on contraception. Three had routine or alternative care as the comparison (Gilliam 2004; Tang 2014; Torres 2014); in the fourth, the control group had no intervention (Saeed 2008).

Eight trials provided more than one contact. In addition to contraception, some addressed broader health education or parenting issues while others provided logistical support or case management. The interventions involved one or more home visits (Quinlivan 2003; Black 2006; Bashour 2008; Bolam 1998; Barnet 2009), clinic contacts (O'Sullivan 1992), or phone sessions (Katz 2011; Simmons 2013).

All reports had some information regarding intervention fidelity (Table 2). All reports had information on the intervention content or its development. In most trials, clinicians provided the education and had some intervention training although the intensity of training varied. In a few studies, the women who provided the intervention had demographics similar to those of the participants.

2. Intervention fidelity information.

| Study | Curriculum or manual | Provider credentials | Training for intervention | Assessed adherence to protocol | Assessed intervention receipta | Fidelity criteria met |

| O'Sullivan 1992 | 4 goals and specific services identified; which professionals provide each component | Directed by nurse practitioner; providers included social worker, pediatrician and nurse practitioner, volunteers | Volunteers were 'trained' | _ | _ | 3 |

| Bolam 1998 | Format and content identified for sessions including key messages | 3 health educators, 2 midwives, 1 community health worker | Providers were 'trained' to give the health education | Investigators monitored weekly and gave feedback | Knowledge of infant health issues (primary outcome) | 5 |

| Quinlivan 2003 | Structured home visits outlined in report | Certified midwives | _ | _ | Knowledge of contraception (primary outcome) | 3 |

| Gilliam 2004 | Developed counseling program, video, pamphlet; development described | Resident physicians, nurses for additional counseling | Training session for resident physicians and nurses | _ | Knowledge of OCs (secondary outcome) | 4 |

| Black 2006 | Curriculum with 19 lessons; order could vary after 2 sessions | 2 Black women, college‐educated, in their 20s, single mothers, living independently | 'Extensive' training provided | Weekly supervisory sessions | _ | 4 |

| Bashour 2008 | Objectives for each visit; breastfeeding in visits 2 and 3, family planning in visit 4 | Registered midwives | 5 days of special training | _ | _ | 3 |

| Saeed 2008 | Counseling leaflet used | Physicians | Providers had 40‐minute training on leaflet and interview methods. | _ | _ | 3 |

| Barnet 2009 | Structured software (computer‐assisted motivational intervention (CAMI)); 20‐min stage‐matched motivational interviewing (MI); parenting curriculum | African American paraprofessional women from participants' communities; had empathetic qualities, rapport with adolescents, community knowledge | 2.5 days on transtheoretical model, MI, and CAMI | First 4 months, counselors met biweekly with MI supervisor (discussed audiotapes and gave feedback) | _ | 4 |

| Katz 2011 | Curriculum with standardized format and session structure; teen workbooks with visual material on topics | Masters‐level young women of similar racial‐ethnic background as teens | _ | Process evaluation included delivery | _ | 3 |

| Simmons 2013 | _ | 2 personal assistants with contraceptive counseling experience (OBGYN resident, 4th‐year medical student) | _ | Contacts planned; additional counseling as needed | _ | 2 |

| Tang 2014 | 1‐minute script | Research assistants | _ | _ | _ | 2 |

| Torres 2014 | Written structured script on all contraceptive methods by effectiveness | _ | _ | _ | Knowledge assessed with 'widely accepted instrument' | 2 |

aAssessed participants' understanding and skills regarding the intervention.

Outcomes included contraceptive use, pregnancy, and contraceptive knowledge. All trials assessed contraceptive use; six reported on repeat pregnancy or second birth. In Characteristics of included studies, we focus on the primary and secondary outcomes for this review. Studies may have had additional outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

Details for each study can be found in Characteristics of included studies. The trial with only a conference abstract had limited design information (Torres 2014).

Intervention quality

All reports provided some documentation of intervention content and most had implementation information (Table 2). A few did not provide much or any information on training of providers for the specific intervention. Only five reported on how the investigators assessed delivery adherence, i.e., whether the intervention was provided as intended.

Outcome assessment was limited in many studies (Table 3). That is, three of six trials that assessed pregnancies or repeat births had some objective validation, such as pregnancy test or vital statistics. Some studies assessed or reported contraceptive use with one dichotomous item, while others had structured questionnaires. Three studies had limited follow‐up periods. The short‐term nature of several interventions may also have limited the usefulness of the effectiveness measures.

3. Evidence quality.

| Study | Intervention fidelity < 4 items | Randomization; allocation concealment | Outcome assessment | Follow‐up period | Loss > 20% | Evidence qualitya,b | Evidence of effectiveness |

| Barnet 2009 | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | High | _ |

| Black 2006 | _ | _ | ‐1 | _ | _ | Moderate | Fewer repeat births (by 24 months) |

| Gilliam 2004 | _ | _ | _ | _ | ‐1 | Moderate | _ |

| Katz 2011 | ‐1 | _ | _ | _ | _ | Moderate | _ |

| Simmons 2013 | ‐1 | _ | _ | _ | _ | Moderate | _ |

| Bashour 2008 | ‐1 | _ | _ | ‐1 | _ | Moderate to lowc | _ |

| Bolam 1998 | _ | _ | ‐1 | _ | ‐1 | Low | Use of contraception (at 6 months) |

| Quinlivan 2003 | ‐1 | _ | ‐1 | _ | _ | Low | Effective use of contraception (at 6 months) |

| Tang 2014 | ‐1 | _ | _ | ‐1 | _ | Low | _ |

| O'Sullivan 1992 | ‐1 | ‐1 | ‐1 | _ | _ | Very low | Fewer repeat pregnancies (by 18 months) |

| Saeed 2008 | ‐1 | _ | ‐1 | ‐1 | _ | Very low | Use of contraception (at 8 to 12 weeks) |

| Torres 2014 | ‐1 | ‐1 | ‐1d | _ | ‐1d | Very low | Use of highly effective contraception (at 3 months) |

aRCTs considered high quality then downgraded: 1) intervention fidelity < 4 criteria; 2) no information on randomization sequence generation or allocation concealment, or risk of bias was high for one; 3) outcome assessment lacked an objective measure (e.g., pregnancy test or structured questionnaire for contraceptive use); 4) follow‐up < 3 months for contraceptive use or < 6 months for pregnancy; 5) loss to follow‐up > 20% bSensitivity analysis included evidence of moderate or high quality cModerate for contraceptive use; low for pregnancy dUnknown; preliminary report

Allocation

Five trials provided information on sequence generation and used sealed envelopes to conceal the allocation (Bolam 1998; Quinlivan 2003; Gilliam 2004; Bashour 2008; Tang 2014). Four had information on the randomization procedure but nothing on allocation concealment (Saeed 2008; Barnet 2009; Katz 2011; Simmons 2013). Three did not have information on sequence generation or concealment (O'Sullivan 1992; Black 2006; Torres 2014).

Blinding

Blinding of assignment was not possible in many trials, given the nature of the interventions. However, the outcome assessors were blind to group of allocation in three trials (Bolam 1998; Bashour 2008; Saeed 2008). Research team members were blinded in three studies (Gilliam 2004; Simmons 2013; Tang 2014). One trial was open (Torres 2014).

Incomplete outcome data

Losses to follow‐up were greater than 20% in two trials: Bolam 1998 (25% at three months and 27% at six months) and Gilliam 2004 (52% by one year). Losses were not as high overall as for some trials in contraceptive education (Lopez 2013).

Other potential sources of bias

Black 2006 excluded participants after randomization due to missing data. Barnet 2009 excluded one participant who had a stillborn infant and one whose two‐month‐old infant died.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Counseling (one contact)

Four studies provided a single counseling session focused on contraception (Gilliam 2004; Saeed 2008; Tang 2014; Torres 2014). Torres 2014 also reportedly facilitated access to the woman's desired contraceptive method, but we had limited information from the conference abstract. Three trials were conducted in the USA and one in Pakistan (Saeed 2008). Gilliam 2004 focused on young women (<= 25 years old), two trials included participants from age 14 up to 45 years (Tang 2014) or up to 50 years (Torres 2014), and Saeed 2008 did not have any age specifications.

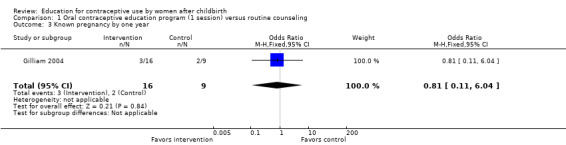

Gilliam 2004 (N = 33) provided a multi‐component intervention of counseling, videotape about oral contraceptives (OC), and written material. The comparison group had usual care. The experimental and comparison groups were not significantly different in the proportions that continued oral contraceptive use at one year (Analysis 1.1), those who switched the type of contraceptive used (Analysis 1.2), or known pregnancies (Analysis 1.3). The investigators noted that the sample size was not sufficient to detect a 20% difference between groups, due to resource limitations.

In Saeed 2008 (N = 648), the experimental group received informal counseling on contraception plus a pamphlet. The control group had no intervention. At 8 to 12 weeks postpartum in Saeed 2008, women in the counseling group were more likely to report using contraception (OR 19.56; 95% CI 11.65 to 32.83) (Analysis 2.1). For choice of contraceptive, all women in the counseling group planned to use a modern contraceptive method by six months postpartum compared to a third of the control group (Peto OR 18.53, 95% CI 13.15 to 26.12) (Analysis 2.2). The physician‐assessor was reportedly blinded to study arm.

Tang 2014 (N = 800) used a one‐minute script on long‐acting, reversible contraception (LARC). Long‐acting methods include intrauterine contraception and the subdermal implant. Women were followed up by phone after the six‐week visit. The comparison group received routine counseling at the hospital, which was not standardized. Despite the large sample size, the study arms did not differ significantly for LARC use (Analysis 3.1), interest in but not using LARC (Analysis 3.2), or use of any contraceptive method (Analysis 3.3).

For Torres 2014 (N = 121), we had preliminary information from the conference abstract. Results were from three months of follow‐up. The trial plans to follow 362 participants for 36 months (12 months for the primary outcome) with completion in 2016. Women with a preterm birth received structured counseling on the relative effectiveness of contraceptive methods, while the comparison group had usual care. The experimental group also reportedly had some assistance with access to the desired contraceptive method, but details were not available. The group with structured counseling was more likely than the routine care group to be using a highly effective contraceptive method at three months (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.83) (Analysis 4.1). Mean increase in contraceptive knowledge was also higher for structured counseling compared to routine care (MD 2.30, 95% CI 2.00 to 2.60) (Analysis 4.2). No detail was available regarding the knowledge assessment.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral contraceptive education program (1 session) versus routine counseling, Outcome 1 Continuation of oral contraceptives at one year.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral contraceptive education program (1 session) versus routine counseling, Outcome 2 Switched contraceptives by one year.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral contraceptive education program (1 session) versus routine counseling, Outcome 3 Known pregnancy by one year.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus no counseling, Outcome 1 Use of any contraceptive at 8 to 12 weeks postpartum.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus no counseling, Outcome 2 Choice of modern contraceptive (using or plan to use) at 8 to 12 weeks postpartum.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 LARC script (1‐minute) + routine counseling versus routine counseling, Outcome 1 LARC use after 6 weeks.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 LARC script (1‐minute) + routine counseling versus routine counseling, Outcome 2 Interested in but not using LARC after 6 weeks.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 LARC script (1‐minute) + routine counseling versus routine counseling, Outcome 3 Using any contraceptive after 6 weeks.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Focused contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus usual care, Outcome 1 Use of highly effective contraceptive method at 3 months.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Focused contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus usual care, Outcome 2 Increase in contraceptive knowledge by 3 months.

Programs with two or more contacts (home, clinic, or phone)

Eight trials provided interventions that covered a range of health and lifestyle issues, including contraception. Five targeted adolescents; four were conducted in the eastern USA (O'Sullivan 1992; Black 2006; Barnet 2009; Katz 2011) and one in Australia (Quinlivan 2003). The three that included adult women were conducted in Syria (Bashour 2008), Nepal (Bolam 1998), and the northwestern USA (Simmons 2013).

Adolescents

Five trials focused on adolescents, three of which involved home visiting.

For Quinlivan 2003 (N = 139), young women in the experimental group had a structured home‐visiting program as opposed to standard home visits. Girls in the experimental group were more likely to have effective contraceptive use at six months than those in the comparison group (OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.35 to 7.79) (Analysis 5.1). We did not have sufficient data to analyze contraceptive knowledge in this review. Reportedly, the mean difference in contraceptive knowledge at six months favored the experimental group (reported MD 0.92; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.52).

Black 2006 (N = 181) evaluated second births during home visits. The experimental group had multiple home visits over two years, while the controls had usual care. The mean number of intervention visits was 6.63 (standard deviation 6.58). The adolescents in the treatment group were less likely to have had a second birth within two years than the usual care group (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.17 to 1.00) (Analysis 6.1).

For Barnet 2009 (N = 237), the experimental groups received a computer‐assisted motivational intervention (CAMI) plus a parenting curriculum (CAMI+) and case management. The comparison groups had the CAMI or usual care. The study arms did not differ significantly for repeat births by 24 months from index birth (Analysis 7.1). Births were assessed through Vital Statistics; 100% of the index births were located. The repeat birth rates for both CAMI groups were lower than, but not significantly different from, the rate for the usual care group. The figures were 13.8% for CAMI plus parenting curriculum (CAMI+), 17.2% for CAMI‐only, and 25% for usual care. Abortion information was obtained at the follow‐up interview. The investigators provided the percentages for reported abortions: CAMI+ 22%, CAMI‐only 20%, and usual care 21%.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Home visiting: structured versus routine, Outcome 1 Effective use of contraception at 6 months.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Home‐based mentoring (multiple visits) versus usual care, Outcome 1 Second birth by 24 months.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Computer‐assisted motivational interviewing (CAMI) with parenting curriculum versus CAMI‐only versus usual care, Outcome 1 Repeat birth by 24 months.

The other two trials for adolescents provided clinic‐based services plus reminders or cell‐phone counseling.

In O'Sullivan 1992 (N = 243), the experimental group had special services provided within the well‐baby clinic, including reminder contacts. The comparison group had the usual well‐baby care. The teenagers in the experimental group were less likely to have a repeat pregnancy (self‐reported) by 18 months compared to the control group (OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.70) (Analysis 8.1). The difference in pregnancies was largely within the subgroup of clinic dropouts. Of the control group, 29/91 had a repeat pregnancy versus 9/60 in the experimental group (data not shown).

Katz 2011 (N = 249) provided a cell‐phone counseling intervention, supplemented by quarterly group sessions. Subsequent pregnancy was assessed via cell phone calls at 3, 9, 15, and 21 months. Pregnancy status was confirmed by urine pregnancy tests at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. Pregnancy rates did not differ significantly between the study groups during the two‐year follow‐up (Analysis 9.1). The rates were 31% for the group with the cell phone intervention and 36% for the usual care group.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Special postpartum care (including contraception) versus routine services (multiple well‐baby contacts), Outcome 1 Repeat pregnancy (self‐report) by 18 months.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Phone counseling + follow‐up versus usual services, Outcome 1 Repeat pregnancy by 24 months.

Adult and younger women

Of three interventions for women of various ages, one provided phone follow‐up and two involved home visits.

In Simmons 2013 (N = 50), the special intervention group received reminders and assistance with follow‐up visits as well as counseling by phone. The comparison group had usual care. The groups did not differ significantly for LARC placement by three months in this small trial (Analysis 9.2).

In Bashour 2008 (N = 903), the experimental group had up to four home visits, with the last one focusing on family planning. One study group had a single visit without family planning and the control group had usual care, which did not include a home visit. At four months, the study groups did not differ significantly in contraceptive use (Analysis 10.1; Analysis 10.2) or in self‐reported pregnancy (Analysis 10.3; Analysis 10.4).

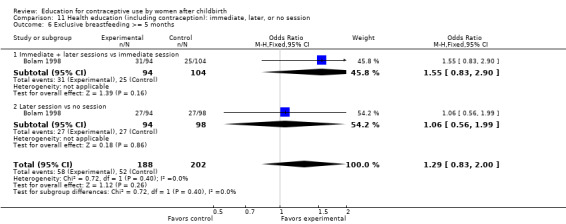

For Bolam 1998 (N = 540), two of the four study groups had health education during their postpartum hospital stay. One of those had a second session at three months that included family planning. A third group had the educational session at three months, and the fourth received no health education (Types of interventions). We grouped those with a health education session during their postpartum hospital stay (with or without a later session) and those with a later session or no session. The two groups did not differ significantly for contraceptive use at three months (Analysis 11.1). However, at six months, the group with an immediate postpartum session was more likely to use contraception than the group with a later or no session (OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.50) (Analysis 11.2). We also compared the arms within those groups at six months (three‐month data were not available). Women with an immediate and later session did not differ significantly in contraceptive use from those with one immediate session (Analysis 11.3). Also, contraceptive use among women with only the later session was not significantly different from those with no educational session (Analysis 11.3). Exclusive breastfeeding was emphasized in the immediate postpartum session. The study arms did not differ significantly in exclusive breastfeeding at three months or for more than five months (Analysis 11.4 to Analysis 11.6).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Phone counseling + follow‐up versus usual services, Outcome 2 LARC use at 3 months.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Home visiting: 4 visits versus 1 visit versus usual care, Outcome 1 Contraception use at 4 months: 4 visits versus 1 visit.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Home visiting: 4 visits versus 1 visit versus usual care, Outcome 2 Contraception use at 4 months: 1 visit versus usual care.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Home visiting: 4 visits versus 1 visit versus usual care, Outcome 3 Pregnancy (self‐report) at 4 months postpartum: 4 visits versus 1 visit.

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Home visiting: 4 visits versus 1 visit versus usual care, Outcome 4 Pregnancy (self‐report) at 4 months postpartum: 1 visit versus usual care.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Health education (including contraception): immediate, later, or no session, Outcome 1 Contraception use at 3 months: immediate session versus no immediate session.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Health education (including contraception): immediate, later, or no session, Outcome 2 Contraception use at 6 months: immediate session versus no immediate session.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Health education (including contraception): immediate, later, or no session, Outcome 3 Contraception use at 6 months.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Health education (including contraception): immediate, later, or no session, Outcome 4 Exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months: immediate session versus no immediate session.

11.6. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Health education (including contraception): immediate, later, or no session, Outcome 6 Exclusive breastfeeding >= 5 months.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Sensitivity analysis

We focus here on the six trials with evidence of moderate or high quality (Table 3). One USA study had evidence of intervention effectiveness (Black 2006). In that trial, the experimental group had enhanced services through a home‐visiting program versus usual care for the controls. The experimental group had fewer repeat pregnancies or second births within two years compared to the control group. Second births were assessed during home visits.

The other five trials with evidence of moderate or high quality showed no effect of the intervention. All assessed contraceptive use and three examined pregnancies (a fourth had low quality evidence for pregnancy). The three trials with adolescents or young women provided the following: one multi‐component session (without sufficient power to detect differences) (Gilliam 2004), computer‐assisted motivational interviewing plus case management (Barnet 2009), and a cell‐phone counseling intervention with multiple contacts (Katz 2011). Of the two trials that included adult women, one had up to four home visits with one visit focused on family planning (Bashour 2008) and the other provided reminders and assistance with follow‐up visits as well as phone counseling (Simmons 2013).

Other results

Six trials provided evidence of low or very low quality in our assessment. Of three studies with low quality evidence, two showed evidence of effect on contraceptive use (Bolam 1998; Quinlivan 2003). An Australian trial was based on a home‐visiting program for adolescents, and compared structured versus standard home visits (Quinlivan 2003). The group with structured visits was more likely to use effective contraception at six months than the group with routine care. From Nepal, a four‐arm study provided health education for women of varying ages, including family planning for two groups at different times (Bolam 1998). Three trials with very low quality evidence also showed some effect on pregnancy or contraceptive use (Table 3). A recent study was downgraded largely because of limited information in the preliminary report (Torres 2014). This trial may be rated higher when more information is available on design and implementation.

Of nine studies with low, moderate, or high quality evidence, three showed any significant difference between comparison groups (Table 1). With so few studies overall, we could not detect any pattern based on number of contacts or population of focus. Half of the programs showed some evidence of effect, regardless of the number of contacts.

Of six trials that focused on adolescents or young women, three showed some effect of the intervention. Two had fewer repeat pregnancies or births within the experimental group; both involved home‐visiting programs. The third provided clinic services and reminders, and showed more effective use of contraception in the special‐intervention group.

Of six trials that included women of various ages, three had some effect on contraceptive use. They provided one counseling session versus none, structured counseling versus usual care, and health education including family planning.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We did not combine any trials in meta‐analysis due to varying interventions and outcome measures. The included trials represented various types of postpartum education: one contact or multiple‐session programs in five countries. Several interventions were provided during the postpartum hospital stay, while others began two or three weeks later. In some trials, family planning education was integrated with other health education or health services. The six trials showing positive effects were conducted in Australia, Nepal, Pakistan, and the USA. However, five provided low quality evidence. We did not examine interventions for postpartum contraception that began during the prenatal period. For example, Adanikin 2013 assigned women to either three sessions in the last trimester or the usual single session at the six‐week postpartum visit. Women with the prenatal sessions were more likely to use modern contraceptives at six months compared with the group that only had one postnatal session.

Clinics are likely to vary in the type and amount of usual services. In an urban teaching hospital in the USA, a retrospective study examined factors associated with repeat pregnancy among first‐time adolescent mothers (Damle 2015). Lower risk of rapid repeat pregnancy was found among those with a postpartum visit by eight weeks and who initiated use of long‐acting reversible contraception (LARC) by eight weeks. Special populations may also benefit from targeted programs. In Shanghai, migrant women had an unintended pregnancy rate about four times that of permanent residents (Huang 2014). A contraceptive services program provided counseling and a choice of contraceptive methods for migrant women. The education was provided in the maternity ward prior to delivery, with a second session if time was too limited. Long‐acting methods available prior to discharge included tubal ligation, IUD insertion immediately after delivery, and injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Condoms were provided to those who did not desire a long‐acting method. Contraceptive use at 12 months was 97%, with IUD and condom use at about 39% each followed by tubal ligation at 8% and DMPA at 7%.

Costs for home‐visiting or multiple‐contact programs could be a limiting factor for many settings. Two studies in this review addressed costs. In O'Sullivan 1992, both groups received well‐baby care in the clinic. The hospital estimated the cost per visit to be lower for special care than routine care. The savings were attributed to several factors, such as combining services and not using medical residents who would need training and faculty supervision. In a 2010 article from Barnet 2009, the weighted mean costs for any CAMI were US $2064 per teen. Costs per teen were US $1449 for CAMI‐only and US $2635 for CAMI + parenting curriculum.

Quality of the evidence

Six studies had evidence of moderate or high quality (Table 3), but the overall quality of evidence was moderate to low. Most evidence of effectiveness came from trials of low or very low quality. Our assessment considers the intervention design and implementation as well as the basic trial design. For the latter, Figure 1 summarizes the risk of bias for the review overall. Risk of bias for individual trials is shown in Figure 2. Most trials were published since the first CONSORT guidelines, which have been updated (Schulz 2010), so the trials would be expected to have adequate reporting.

1.

Risk of bias graph: authors' judgements about risk of bias as percentages across all included studies

2.

Risk of bias summary: authors' judgements about risk of bias item for each included study

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The trials varied in the types of educational programs, settings, and populations served. With so few studies overall, we could not see any pattern based on number of contacts or population of focus. Half of the interventions led to more contraceptive use or fewer unplanned pregnancies. One with home visiting for adolescent mothers had moderate quality evidence. However, most of the trials that showed some effect provided low quality information. Those interventions could be improved by strengthening the program design and implementation. Still, given the associated costs and logistics, some programs would not be feasible in many settings.

Implications for research.

The overall quality of evidence was moderate to low. The evidence of intervention effectiveness was mostly low quality. Reasons included the design and implementation of the intervention and the trial, as well as reporting limitations. Some trials did not report program training for providers, assessment of adherence to the intervention protocol, or measurement of participants' knowledge and skills after the program. Some shortcomings may result from space limitations in journals. However, many trials did not have an objective outcome measure, i.e., pregnancy test or structured questionnaire for contraceptive use. Valid and reliable outcome measures are needed to obtain meaningful results.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 July 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches updated |

| 5 May 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | 3 new trials did not change conclusions |

| 28 January 2015 | New search has been performed | Included 3 new trials included (Simmons 2013; Tang 2014; Torres 2014); excluded 1 trial that was previously included but did not have data on our primary outcomes (Proctor 2006) |

| 7 January 2015 | Amended | Edited wording of Objectives and Types of outcome measures to reflect focus of current review |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 4, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 June 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New trials did not show evidence of effectiveness. We assessed the quality of evidence (Data synthesis), which included quality of intervention evidence (Table 15) and then overall quality of evidence (Table 3). |

| 30 May 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches updated; two new trials included (Barnet 2009; Katz 2011). |

| 9 November 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | We had 7 trials to add. We excluded studies that had issues regarding unit of analysis, i.e., 2 studies from the original review (Foreit 1993; Sayegh 1976).Consequently, the conclusions changed in this version. |

| 25 June 2009 | New search has been performed | New trials added (Bashour 2008; Black 2006; Gilliam 2004; Proctor 2006a; Quinlivan 2003; Saeed 2008). O'Sullivan 1992 was moved to 'included studies,' due to defining postpartum education as that which occurred within 1 month of delivery. Added searches of clinical trial databases. |

| 15 June 2009 | Amended | Expanded time frame for postpartum education to include programs initiated in less than a month after delivery. Included use of health care services as an outcome. |

| 21 May 2009 | Amended | Authors added to lead update (LM Lopez, DA Grimes) |

| 15 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 March 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

In 2012, S Mullins of FHI 360 helped review search results and conducted the second data abstraction for the new trials.

For the 2006 revision, M Gulmezoglu of WHO extracted data from Nacar 2003, which was published in Turkish. From FHI 360, C Manion searched the electronic databases.

The 1999 Cochrane Review was an update of a pre‐Cochrane review (Hay‐Smith 1994). The original authors acknowledge the assistance provided by V Kallianes and B Winikoff of the Population Council in identifying research on this topic for the 1999 review and the assistance from A Lusher of the Oxford Cochrane Centre in developing the search strategy for the 2002 update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search 2015

Because we expanded some of the strategies, we ran certain searches from the initiation of the database. For others, date limitations are shown.

MEDLINE via PubMed (7 July 2015)

("Contraception"[Mesh] OR "Contraception Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Agents"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Devices"[Mesh] OR "family planning") AND (educat* OR counsel* OR communicat* OR "information dissemination" OR intervention* OR choice OR choose OR use) AND ("Postpartum Period"[Mesh] OR "Postnatal Care"[Mesh] OR postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR "repeat pregnancy"[tiab] OR mothers[ti]) AND (Clinical Trial[ptyp])

CENTRAL (2015, Issue 2 (on 3 March 2015))

Title, Abstract, Keywords: contracept* OR family planning AND Title, Abstract, Keywords: counsel* OR communicat* OR educat* OR information disseminat* OR intervention OR choice OR choose OR use AND Title, Abstract, Keywords: postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR repeat pregnancy OR mothers

POPLINE (3 March 2015)

All fields: counsel* OR educat* or communicat* OR information dissemination OR choice OR choose OR use Keyword: Contraception AND Keyword: Postpartum Filter by keyword: Research report

CINAHL (2 December 2014)

counseling or sex education or client education or health promotion or teaching or counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach* AND postnatal period or postnatal* or post?natal* or postpartum or post?partum or post‐partum or postpartal* or maternity or maternal or mother* or puerperium AND birth control or contraceptive devices or family planning or sterilization?sex or (family n6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* n6 prevent*) or (birth n6 control) AND clinical trial* or clinical stud* or randomized n controlled n trial* or randomised n controlled n trial* or random*

Published Date: 20120101‐20141231

Web of Science (2 December 2014)

TOPIC:(contracept*) AND TOPIC: (educat* OR counsel* OR communicat* OR "information dissemination" OR intervention* OR choice OR choose OR use) AND TOPIC: (postpartum OR postnatal) Refined by: DOCUMENT TYPES: ( ARTICLE OR MEETING ABSTRACT OR PROCEEDINGS PAPER ) Timespan: 2012‐2014 Indexes: SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH

ClinicalTrials.gov (2 December 2014)

Search terms: (postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR repeat pregnancy) AND (contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visit* OR family planning) Study type: Interventional Conditions: NOT (preterm OR low birth weight OR HIV OR PCOS OR labor OR congenital OR influenza OR drug OR diabetes) Interventions: NOT (insertion OR supplement* OR caesarean) Title acronym/Titles: NOT (depression OR violence OR exercise OR IVF OR chlamydia OR immunization OR smokers OR smoking OR smoke OR preeclampsia OR pain OR obese OR obesity OR weight OR nutrition) Gender: Studies with female participants First received: 01/01/2012 to 12/02/2014

ICTRP (3 March 2015)

Title: postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR maternal OR maternity OR mothers OR repeat pregnancy Intervention: contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visits OR family planning Recruitment status: All Date of registration: 1 January 2012 to 3 March 2015

Appendix 2. Previous searches

2012

MEDLINE via PubMed (01 January 2009 to 29 May 2012)

("Contraception"[Mesh] OR "Contraception Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Agents"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Devices"[Mesh] OR "family planning") AND (educat* OR counsel* OR communicat* OR "information dissemination" OR intervention* OR choice OR choose OR use) AND ("Postpartum Period"[Mesh] OR "Postnatal Care"[Mesh] OR postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal) Limits Activated: Clinical Trial, Randomized Controlled Trial

CENTRAL (2009 to 29 May 2012)

contracept* OR family planning in Title, Abstract or Keywords AND counsel* OR communicat* OR educat* OR information disseminat* OR intervention OR choice OR choose OR use in Title, Abstract or Keywords AND postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal in Title, Abstract or Keywords

POPLINE (2009 to 29 May 2012)

title/keyword ‐(counseling/clinic activities/counselors/family planning education/health education/population education/family planning program*/sex education/family planning center*/teaching material*/counsel*/debrief*/educat*/teach*/birth control*/ family planning) & (postpartum program*/puerperium/postpartum women/maternal‐child health service*/maternal health service*/postnatal*/post‐partum/postpartum/postpartal*/puerperium/maternity/maternal/mother*) & (clinical trial/random*) OR abstract ‐(counseling/clinic activities/counselors/family planning education/health education/population education/family planning program*/sex education/family planning center*/teaching material*/counsel*/debrief*/educat*/teach*/birth control*/ family planning) & (postpartum program*/puerperium/postpartum women/maternal‐child health service*/maternal health service*/postnatal*/post‐partum/postpartum/postpartal*/puerperium/maternity/maternal/mother*) & (clinical trial/random*)

CINAHL (through Ebscohost) (2009 to 30 May 2012)

counseling or sex education or client education or health promotion or teaching or counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach* AND postnatal period or postnatal* or post?natal* or postpartum or post?partum or post‐partum or postpartal* or maternity or maternal or mother* or puerperium AND birth control or contraceptive devices or family planning or sterilization?sex or (family n6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* n6 prevent*) or (birth n6 control) AND clinical trial* or clinical stud* or randomized n controlled n trial* or randomised n controlled n trial* or random*

PsycINFO (2009 to 30 May 2012)

(counseling or sex education or client education or health promotion or teaching or counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach*) AND (postnatal period or postnatal* or post?natal* or postpartum or post?partum or post‐partum or postpartal* or maternity or maternal or mother* or puerperium) AND (birth control or contraceptive device* or contraceptive agent* or "family planning" or sterilization?sex or family N6 planning or contracept* or pregnan* N6 prevent* or birth N6 control) AND (clinical trial* or clinical stud* or randomized N1 controlled N1 trial* or randomised N1 controlled N1 trial* or random*)

ClinicalTrials.gov (29 May 2012)

Search terms: (postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR matern* OR mothers) AND (contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visit* OR family planning) Conditions: NOT (preterm OR low birth weight OR HIV OR pregnancy OR labor OR congenital OR influenza OR drug) Interventions: NOT (insertion OR supplement* OR caesarean)

ICTRP (29 May 2012)

Title: postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR maternal OR maternity OR mothers Condition: NOT (preterm OR low birth weight OR HIV OR pregnancy) Intervention: (contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visits OR family planning)

2009

MEDLINE via Pubmed (20 May 2009)

("Contraception"[Mesh] OR "Contraception Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Agents"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Devices"[Mesh] OR "family planning") AND (educat* OR counsel* OR communicat* OR "information dissemination" OR intervention* OR choice OR choose OR use) AND ("Postpartum Period"[Mesh] OR "Postnatal Care"[Mesh] OR postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal) AND (Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Clinical Trial, Phase I[ptyp] OR Clinical Trial, Phase II[ptyp] OR Clinical Trial, Phase III[ptyp] OR Clinical Trial, Phase IV[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Controlled Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Evaluation Studies[ptyp])

CENTRAL (20 May 2009)

contracept* OR family planning in Title, Abstract or Keywords AND counsel* OR communicat* OR educat* OR information disseminat* OR intervention OR choice OR choose OR use in Title, Abstract or Keywords AND postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal in Title, Abstract or Keywords

EMBASE (19 February 2009)

1. exp COUNSELING/ 2. exp HEALTH EDUCATION/ 3. SEXUAL EDUCATION/ or TEACHING/ or PATIENT SATISFACTION/ 4. (counsel$ or debrief$ or educat$ or teach$).ti,ab. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. exp POSTNATAL CARE/ 7. exp MATERNAL CARE/ 8. MATERNAL BEHAVIOR/ 9. HOSPITAL DISCHARGE/ 10. (postnatal$ or postpartum or post‐partum or post partum or postpartal$).ti,ab. 11. (maternity or maternal or mother$).ti,ab. 12. puerperium.ti,ab. 13. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. exp BIRTH CONTROL/ or exp CONTRACEPTION/ 15. exp CONTRACEPTIVE DEVICE or exp CONTRACEPTIVE AGENT/ 16. exp GESTAGEN/ 17. ((family adj6 planning) or contracept$ or (pregnan$ adj6 prevent$)).ti,ab. 18. (birth adj6 control).ti,ab. 19. 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20. 5 and 13 and 19 21. CLINICAL STUDY/ or CLINICAL ARTICLE/ or CASE CONTROL STUDY/ or LONGITUDINAL STUDY/ or MAJOR CLINICAL STUDY/ or PROSPECTIVE STUDY/ or CLINICAL TRIAL/ or MULTICENTER STUDY/ or PHASE 3 CLINICAL TRIAL/ or PHASE 4 CLINICAL TRIAL/ or RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL/ or CONTROLLED STUDY/ or CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ or DOUBLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ or INTERMETHOD COMPARISON/ or SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ or PLACEBO/ 22. (allocat$ or assign$ or compar$ or control$ or cross over$ or crossover$ or factorial$ or latin square or latin‐square or followup or follow up or placebo$ or prospective$ or random$ or trial$ or versus or vs).ti,ab. 23. (clinic$ adj25 study).ti,ab. 24. (clinic$ adj25 trial).ti,ab. 25. (singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 26. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27. NONHUMAN/ OR ANIMAL/ OR ANIMAL EXPERIMENT/ 28. HUMAN/ AND (NONHUMAN/ OR ANIMAL OR ANIMAL EXPERIMENTATION/) 29. 27 not 28 30. 26 not 29 31. 20 and 30

POPLINE (19 February 2009)

title/keyword ‐(counseling/clinic activities/counselors/family planning education/health education/population education/family planning program*/sex education/family planning center*/teaching material*/counsel*/debrief*/educat*/teach*/birth control*/ family planning) & (postpartum program*/puerperium/postpartum women/maternal‐child health service*/maternal health service*/postnatal*/post‐partum/postpartum/postpartal*/puerperium/maternity/maternal/mother*) & (clinical trial/random*) OR abstract ‐(counseling/clinic activities/counselors/family planning education/health education/population education/family planning program*/sex education/family planning center*/teaching material*/counsel*/debrief*/educat*/teach*/birth control*/ family planning) & (postpartum program*/puerperium/postpartum women/maternal‐child health service*/maternal health service*/postnatal*/post‐partum/postpartum/postpartal*/puerperium/maternity/maternal/mother*) & (clinical trial/random*)

CINAHL (19 February 2009)

counseling or sex education or client education or health promotion or teaching or counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach* AND postnatal period or postnatal* or post?natal* or postpartum or post?partum or post‐partum or postpartal* or maternity or maternal or mother* or puerperium AND birth control or contraceptive devices or family planning or sterilization?sex or (family n6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* n6 prevent*) or (birth n6 control) AND clinical trial* or clinical stud* or randomized n controlled n trial* or randomised n controlled n trial* or random*

PsycINFO (19 February 2009)

(counseling or sex education or client education or health promotion or teaching or counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach*) AND (postnatal period or postnatal* or post?natal* or postpartum or post?partum or post‐partum or postpartal* or maternity or maternal or mother* or puerperium) AND (birth control or contraceptive device* or contraceptive agent* or "family planning" or sterilization?sex or family N6 planning or contracept* or pregnan* N6 prevent* or birth N6 control) AND (clinical trial* or clinical stud* or randomized N1 controlled N1 trial* or randomised N1 controlled N1 trial* or random*)

ClinicalTrials.gov (16 June 2009)

Search terms: postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR matern* OR mothers Conditions: NOT (preterm OR low birth weight OR HIV OR pregnancy) Interventions: (contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visit* OR family planning) NOT (insertion OR supplement* OR caesarean)

ICTRP (16 June 2009)

Title: postpartum OR post‐partum OR postnatal OR maternal OR maternity OR mothers Condition: NOT (preterm OR low birth weight OR HIV OR pregnancy) Intervention: (contraceptive OR contraception OR births OR home visits OR family planning)

2001

MEDLINE OvidWeb (1966 to 2001 August) and The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register

1. COUNSELING/ 2. SEX COUNSELING/ 3. PATIENT EDUCATION/ 4. HEALTH EDUCATION/ 5. HEALTH PROMOTION/ 6. exp TEACHING/ 7. (counsel$ or debrief$ or educat$ or teach$).ti,ab. 8. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9. POSTNATAL CARE/ 10. exp PUERPERIUM/ 11. MATERNAL HEALTH SERVICES/ 12. MATERNAL‐CHILD HEALTH CENTERS/ 13. MATERNAL BEHAVIOR/ 14. PATIENT DISCHARGE/ 15. (postnatal$ or post‐partum or postpartum or post partum or postpartal$).ti,ab. 16. (maternity or maternal or mother$).ti,ab. 17. puerperium.ti,ab. 18. discharg$.ti,ab. 19. 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20. CONTRACEPTION BEHAVIOR/ 21. exp CONTRACEPTION/ 22. exp CONTRACEPTIVE AGENTS/ 23. exp CONTRACEPTIVE DEVICES/ 24. exp FAMILY PLANNING/ 25. FAMILY PLANNING POLICY/ 26. POPULATION CONTROL/ 27. ((family adj6 planning) or contracept$ or (pregnan$ adj6 prevent$)).ti,ab. 28. (birth adj6 control).ti,ab. 29. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 30. 8 and 19 and 29 31. 30 and human/ 32. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.pt. 33. CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 34. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS/ 35. RANDOM ALLOCATION/ 36. DOUBLE‐BLIND METHOD/ 37. SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD/ 38. CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 39. exp CLINICAL TRIALS 40. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 41. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 42. PLACEBOS/ 43. (placebo$ or random$).ti,ab. 44. RESEARCH DESIGN/ 45. COMPARATIVE STUDY/ 46. exp EVALUATION STUDIES/ 47. exp CASE‐CONTROL STUDIES/ or exp COHORT STUDIES/ 48. (control$ or prospective$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. 49. (latin square or latin‐square).ti,ab. 50. (cross‐over$ or cross over$).ti,ab. 51. factorial$.ti,ab. 52. CROSS‐OVER STUDIES/ 53. 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 54. (animal not (human and animal)).sh. 55. 53 not 54 56. 55 and 31

N.B. for searching The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register please substitute "*" for "$" and "near" for "adj"

EMBASE, OvidWeb (1980 to 2001 August)

1. exp COUNSELING/ 2. exp HEALTH EDUCATION/ 3. SEXUAL EDUCATION/ or TEACHING/ or PATIENT SATISFACTION/ 4. (counsel$ or debrief$ or educat$ or teach$).ti,ab. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. exp POSTNATAL CARE/ 7. exp MATERNAL CARE/ 8. MATERNAL BEHAVIOR/ 9. HOSPITAL DISCHARGE/ 10. (postnatal$ or postpartum or post‐partum or post partum or postpartal$).ti,ab. 11. (maternity or maternal or mother$).ti,ab. 12. puerperium.ti,ab. 13. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. exp BIRTH CONTROL/ or exp CONTRACEPTION/ 15. exp CONTRACEPTIVE DEVICE or exp CONTRACEPTIVE AGENT/ 16. exp GESTAGEN/ 17. ((family adj6 planning) or contracept$ or (pregnan$ adj6 prevent$)).ti,ab. 18. (birth adj6 control).ti,ab. 19. 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20. 5 and 13 and 19 21. CLINICAL STUDY/ or CLINICAL ARTICLE/ or CASE CONTROL STUDY/ or LONGITUDINAL STUDY/ or MAJOR CLINICAL STUDY/ or PROSPECTIVE STUDY/ or CLINICAL TRIAL/ or MULTICENTER STUDY/ or PHASE 3 CLINICAL TRIAL/ or PHASE 4 CLINICAL TRIAL/ or RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL/ or CONTROLLED STUDY/ or CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ or DOUBLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ or INTERMETHOD COMPARISON/ or SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ or PLACEBO/ 22. (allocat$ or assign$ or compar$ or control$ or cross over$ or crossover$ or factorial$ or latin square or latin‐square or followup or follow up or placebo$ or prospective$ or random$ or trial$ or versus or vs).ti,ab. 23. (clinic$ adj25 study).ti,ab. 24. (clinic$ adj25 trial).ti,ab. 25. (singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 26. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27. NONHUMAN/ OR ANIMAL/ OR ANIMAL EXPERIMENT/ 28. HUMAN/ AND (NONHUMAN/ OR ANIMAL OR ANIMAL EXPERIMENTATION/) 29. 27 not 28 30. 26 not 29 31. 20 and 30

POPLINE (1970 to 2001 August)

1. COUNSELING/ 2. CLINIC ACTIVITIES/ 3. COUNSELORS/ 4. FAMILY PLANNING EDUCATION/ 5. HEALTH EDUCATION/ 6. POPULATION EDUCATION/ 7. FAMILY PLANNING PROGRAMS/ 8. SEX EDUCATION 9. FAMILY PLANNING CENTERS/ 10. TEACHING MATERIALS/ 11. counsel$ or debrief$ or educat$ or teach$ or birth control$ or family planning 12. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 13. POSTPARTUM PROGRAMS/ 14. PUERPERIUM/ 15. POSTPARTUM WOMEN/ 16. MATERNAL‐CHILD HEALTH SERVICES/ 17. MATERNAL HEALTH SERVICES/ 18. postnatal$ or post‐partum or postpartum or postpartal$ or puerperium 19. maternity or maternal or mother$ 20. 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 21. 12 and 20

CINAHL, SliverPlatter (1982 to 2001 October)

1. "Counseling"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 2. "Sexual‐Counseling"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 3. "Patient‐Education"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 4. "Patient‐Discharge‐Education"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 5. "Health‐Education"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 6. "Sex‐Education"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 7. "Health‐Promotion"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 8. "Teaching"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 9. (counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach*) in ti,ab 10. "Postnatal‐Care"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 11. "Postnatal‐Period"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 12. "Puerperium"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 13. "Maternal‐Health‐Services"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 14. "Maternal‐Child‐Health"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 15. "Maternal‐Behavior"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 16. (postnatal* or post natal* or post‐natal* or post‐partum or post partum or postpartum or postpartal*) in ti,ab 17. (maternity or maternal or mother*) in ti,ab 18. puerperium in ti,ab 19. discharg* in ti,ab 20. #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 21. #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 22. explode "Contraception"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 23. explode "Contraceptive‐Agents"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 24. explode "Contraceptive‐Devices"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 25. explode "Family‐Planning"/ all topical subheadings / all age subheadings 26. ((family near6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* near6 prevent*) or (birth near6 control*)) in ti,ab 27. #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 28. #20 and #21 and #27

PsycINFO SilverPlatter (1899 to 2001 October)

1. "Counseling‐" in DE 2. "Sex‐Education" in DE 3. "Client‐Education" in DE 4. "Health‐Education" in DE 5. "Health‐Promotion" in DE 6. "Teaching‐" in DE 7. (counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach*) in ti,ab 8. #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 9. "Postnatal‐Period" in DE 10. (postnatal* or post natal* or post‐natal* or postpartum or post partum or post‐partum or postpartal*) in ti,ab 11. (maternity or maternal or mother*) in ti,ab 12. puerperium in ti,ab 13. #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 14. explode "Birth‐Control" 15. explode "Contraceptive‐Devices" 16. "Family‐Planning" in DE 17. explode "Sterilization‐Sex" 18. (family near6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* near6 prevent*) or (birth near6 control*) 19. #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 20. #8 and #13 and #19

SIGLE SilverPlatter (1980 to 2001 June)

1. (counsel* or debrief* or educat* or teach*) 2. postnatal* or post natal* or post‐natal* or postpartum or post partum or post‐partum or postpartal* 3. maternity or maternal or mother* 4. puerperium 5. #2 or #3 or #4 6. (family near6 planning) or contracept* or (pregnan* near6 prevent*) or (birth near6 control*) 7. #1 and #5 and #6

ASSIA Bowker Saur CD‐ROM (1987 to 2001 November)

1. ft=educat$ 2. ft=advice 3. ft=advise$ 4. ft=debrief$ 5. ft=teach$ 6. ft=counsel$ 7. cs=1 or cs=2 or cs=3 or cs=4 or cs=5 or cs=6 8. ft=postpartum 9. ft=postnatal$ 10. ft=puerperium 11. cs=8 or cs=9 or cs=10 12. ft=pregnan$ prevent$ 13. ft=contracept$ 14. ft=family planning 15. ft=abstinen$ 16. ft=birth control$ 17. ft=fertility regulat$ 18. ft=fertility control$ 19. cs=12 or cs=13 or cs=14 or cs=15 or cs=16 or cs=17 or cs=18 20. cs=7 and cs=11 and cs=19 21. cs=7 and cs=11 22. cs=11 and cs=19

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oral contraceptive education program (1 session) versus routine counseling.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Continuation of oral contraceptives at one year | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.11, 3.99] |

| 2 Switched contraceptives by one year | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.37, 10.92] |

| 3 Known pregnancy by one year | 1 | 25 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.11, 6.04] |

Comparison 2. Contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus no counseling.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Use of any contraceptive at 8 to 12 weeks postpartum | 1 | 600 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 19.56 [11.65, 32.83] |

| 2 Choice of modern contraceptive (using or plan to use) at 8 to 12 weeks postpartum | 1 | 600 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.53 [13.15, 26.12] |

Comparison 3. LARC script (1‐minute) + routine counseling versus routine counseling.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 LARC use after 6 weeks | 1 | 738 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.93, 2.09] |

| 2 Interested in but not using LARC after 6 weeks | 1 | 738 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.95, 1.80] |

| 3 Using any contraceptive after 6 weeks | 1 | 734 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.79, 2.08] |

Comparison 4. Focused contraceptive counseling (1 session) versus usual care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Use of highly effective contraceptive method at 3 months | 1 | 121 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [1.03, 4.83] |

| 2 Increase in contraceptive knowledge by 3 months | 1 | 121 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.30 [2.00, 2.60] |

Comparison 5. Home visiting: structured versus routine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Effective use of contraception at 6 months | 1 | 124 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [1.35, 7.79] |

Comparison 6. Home‐based mentoring (multiple visits) versus usual care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Second birth by 24 months | 1 | 149 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.17, 1.00] |