Abstract

Background

Because nearly 23,000 more neurosurgeons are needed globally to address 5 million essential neurosurgical cases that go untreated each year, there is an increasing interest in task-shifting and task-sharing (TS/S), delegating neurosurgical tasks to nonspecialists, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This global survey aimed to provide a cross-sectional understanding of the prevalence and structure of current neurosurgical TS/S practices in LMICs.

Methods

The survey was distributed to a convenience sample of individuals providing neurosurgical care in LMICs with a Web-based survey link via electronic mailing lists of continental societies and various neurosurgical groups, conference announcements, e-mailing lists, and social media platforms. Country-level data were analyzed by descriptive statistics.

Results

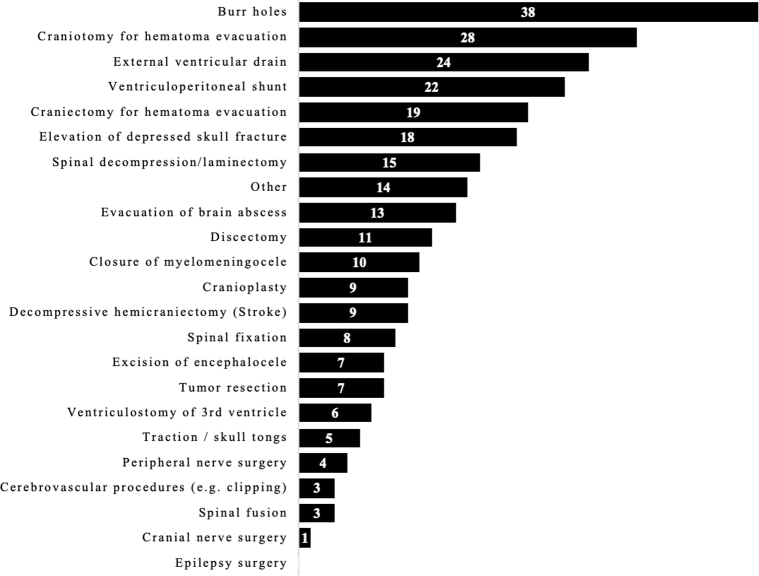

The survey yielded 127 responses from 47 LMICs; 20 countries (42.6%) reported ongoing TS/S. Most TS/S procedures involved emergency interventions, the top 3 being burr holes, craniotomy for hematoma evacuation, and external ventricular drain. Most (65.0%) believed that their Ministry of Health does not endorse TS/S (24.0% unsure), and only 11% believed that TS/S training was structured. There were few opportunities for TS/S providers to continue medical education (11.6%) or maintenance of certification (9.4%, or receive remuneration (4.2%).

Conclusions

TS/S is ongoing in many LMICs without substantial structure or oversight, which is concerning for patient safety. These data invite future clinical outcomes studies to assess effectiveness and discussions on policy recommendations such as standardized curricula, certification protocols, specialist oversight, and referral networks to increase the level of TS/S care and to continue to increase the specialist workforce.

Key words: Capacity, Global health, Global neurosurgery, LMIC, Task-sharing, Task-shifting, Workforce

Abbreviations and Acronyms: DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; LMIC, Low- and middle-income country; MOH, Ministry of Health; TS/S, Task-shifting and task-sharing

Introduction

Neurosurgical task-shifting and task-sharing (TS/S) is the process of delegating clinical tasks to nonneurosurgical specialists, such as general surgeons, general practitioners, or nonphysician clinicians.1, 2 Task-shifting is the redistribution of these duties and clinical autonomy from highly qualified health care workers to those with shorter training and fewer qualifications.3 In contrast, task-sharing uses collaborative teams who transfer tasks to less-qualified cadres, although both a specialist and a less-qualified provider share clinical responsibility and there is iterative communication and training to preserve high-quality outcomes.4

TS/S models most often arise out of necessity to meet the medical demands of a patient population with a limited workforce, and many countries use TS/S for obstetrics, anesthesia, and general surgery.5, 6, 7 In neurosurgery, because approximately 5 million essential neurosurgical cases go untreated each year, and >23,000 more neurosurgeons are needed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to address this treatment gap, we believe that TS/S may already be prevalent in neurosurgery.8 Furthermore, the most recent Disease Control Priorities section on essential surgery indicated that first-level district hospitals should be able to perform burr holes for hematomas and increased intracranial pressure and shunts for hydrocephalus, whereas tertiary-care centers should have the capacity to perform craniotomies and craniectomies, predominantly for neurotrauma.9 However, neurosurgical workforce deficits continue to be significant barriers to such care provision.10 Few neurosurgical TS/S studies have been reported and details of the respective training structures were not clearly defined. For instance, in a 2014 study of operations performed in a Malawi hospital,11 10% of the total 1186 operative cases were neurosurgical (craniotomies or ventriculoperitoneal shunts), and 80% of the neurosurgery cases were treated by clinical officers in a task-shifting model. In 2015, an assessment of 1036 surgeries in a Liberian hospital12 showed that all 31 neurosurgical cases (3.0%) were treated by general surgeons; neither training protocols nor clinical outcomes were discernable from the reported data. Two models of neurosurgical task-sharing have been recently described in the Philippines13 and Australia,14 both of which provided substantially more detail on the training curriculum, competency evaluation, oversight, referral networks, remuneration, and clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, a more global understanding of the prevalence and diversity of TS/S is lacking.

The goal of this study was to obtain a cross-sectional examination of the prevalence and distribution of neurosurgical TS/S within LMICs and to better understand the models of training, scopes of practice, and systemic support that TS/S providers have. The results are intended to inform future discussions on policy and training programs to facilitate timely access to safe and affordable surgical care.

Methods

Survey Design

The survey was designed using a modified Delphi method,15 piloting and refining the questionnaire with input from neurosurgical experts from 20 countries, most with experience living or working in a country striving to expand the neurosurgical workforce. Questions were written to ascertain current practices, particularly as they related to a theoretic task-sharing model outlined by the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery4 and depicted by Robertson et al.13 (Figure 1). Surveys were available in English, French, and Spanish (Appendix 1). The final survey was reviewed by the institutional review board at Harvard University and granted exemption (IRB18-0158). The target audience included neurosurgery providers, defined as any health worker providing interventional neurosurgical treatments (whether supervised or working independently) from LMICs as defined by the July 1, 2018 World Bank Income classifications.16 We divided neurosurgery providers into 4 types: specialist neurosurgeons (dedicated neurosurgery consultants/attending); general surgeons (general surgery consultants/attendings who have not completed a formal residency/registrar/fellowship training in neurosurgery); general practitioners (those with a medical license but without dedicated surgical training); and nonphysician providers (those who are from a nursing background or from some other nonphysician background).

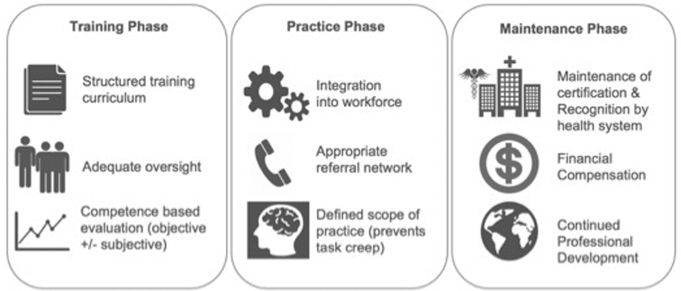

Figure 1.

An ideal task-sharing model divided into three phases of training, practice, and maintenance of providers.

(Figure from Robertson et al.13)

Survey Dispersal

The surveys were available online via Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA). They were distributed via electronic mailing lists of continental societies and various other neurosurgical groups, e-mail to personal contacts, QR codes, and social media platforms through various methods: the Congress of Continental Association of African Neurosurgical Societies distributed through e-mail lists and advertised at the annual meeting in Abuja, Nigeria (global neurosurgery session, 80–100 attendees)17; the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies distributed through e-mail lists and advertised at the Annual Conference in Belgium (approximately 1600 attendees annually)18; the Asian Australasian Society of Neurological Surgeons through their e-mail list; the Chair of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies sent to all subcommittees; and the National Institute for Health Research Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma distributed through e-mail and social media. All 28 neurosurgeons who took part in survey creation assisted in additional dispersal, and coauthors broadcasted on multiple social media outlets (e.g., Facebook groups, Twitter, and neurosurgical WhatsApp collectives). Participation in the survey was voluntary and without remuneration. Given the method of dissemination, a response rate calculation could not be obtained; however, our approach of striving to achieve representation from the maximum number of countries (at the expense of calculating individual response rates) mirrors that of the WFSA Global Anesthesia Workforce Survey.19 At the end of the survey, individuals were invited to list their name in a separate form to receive collaborator status; this was optional. The wide dissemination of the questionnaire through social media platforms precluded a response rate calculation. The survey remained open from July 2018 to February 2019 and data were exported after survey closure.

Data Analysis

All survey data were exported for analysis on February 28, 2019 from Qualtrics into an Excel file and analyzed using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). Workforce data were portrayed with descriptive statistics and tables. Data were grouped according to World Health Organization regions (African Region, Region of the Americas–US and Canada, Region of the Americas–Latin America, South-East Asia Region, European Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region, and Western Pacific Region) and then reported at the level of individual countries. Respondent free text comments were used to represent general themes.

Results

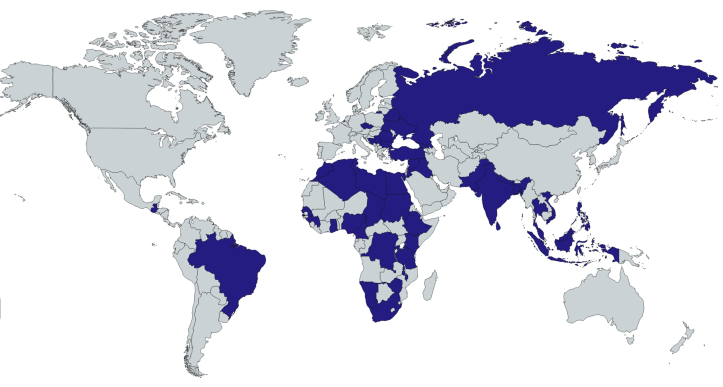

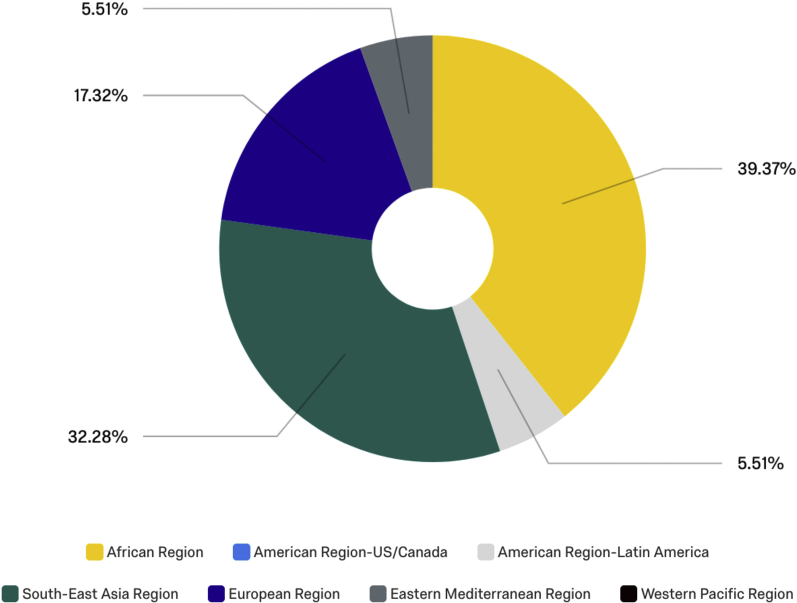

A total of 127 respondents from 47 LMICs (34.3% of 137 LMIC countries) responded to the survey (Figure 2, Table 1). The African World Health Organization Region had 50 participants (39.4% of total respondents), whereas 32.3% of replies were from the South-East Asia Region, 17.3% from the European Region, 5.5% from the Eastern Mediterranean, and 5.5% from the Latin American Region (Figure 3). These countries included Algeria (2), Bangladesh (1), Belarus (1), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1), Brazil (6), Bulgaria (1), Cameroon (1), Cape Verde (1), Chad (1), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (6), Egypt (3), Ethiopia (6), Georgia (1), Ghana (3), Guinea (1), Guatemala (1), India (13), Indonesia (4), Iran (1), Iraq (2), Jordan (1), Kenya (1), Libya (1), Malawi (1), Malaysia (5), Morocco (1), Namibia (1), Nepal (2), Nigeria (11), Pakistan (10), Philippines (3), Romania (2), Russia (1), Rwanda (3), Senegal (1), Serbia (4), South Africa (1), Sri Lanka (1), Sudan (2), Syria (2), Tanzania (1), Thailand (1), Tunisia (1), Turkey (8), Ukraine (3), Vietnam (2), and Zimbabwe (1).

Figure 2.

Cartographic depiction of where low- and middle-income countries survey respondents were located.

(Created with mapchart.net.).

Table 1.

Survey Respondent Demographics

| Variable | Number of Responses (%) |

|---|---|

| World Health Organization Region (n = 127) | |

| African Region | 50 (39.4) |

| South-East Asia Region | 41 (32.3) |

| European Region | 22 (17.3) |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 7 (5.5) |

| American Region-Latin America | 7 (5.5) |

| Training level (n = 127) | |

| Consultant neurosurgeon | 84 (66.1) |

| Neurosurgery trainee | 35 (27.6) |

| Consultant general surgeon | 1 (0.8) |

| General practitioner | 3 (2.4) |

| Other (clinical officer, nonphysician provider) | 4 (3.2) |

| Neurosurgical society member (n = 101) | |

| European Association of Neurosurgical Societies | 36 (35.6) |

| American Association of Neurological Surgeons | 29 (28.7) |

| Continental Association of African Neurosurgical Societies | 28 (27.7) |

| Asian Australasian Society of Neurological Surgeons | 5 (5.0) |

| Latin American Federation of Neurosurgical Societies | 3 (3.0) |

| In-country neurosurgery training availability (n = 99) | |

| Yes | 83 (83.8) |

| Place of practice (all responded with percentages, mean, standard deviation) (n = 127) | |

| Public | 67.6 (39.6) |

| Private | 30.5 (38.7) |

| Faith-based hospital | 2.9 (13.2) |

| Setting (n = 127) | |

| Urban | 118 (92.9) |

| Rural | 9 (7.1) |

Figure 3.

World Health Organization Regions of survey respondents.

Of the 127 respondents, 101 identified as being a member of 1 of the 5 large neurosurgical societies, with most being members of the European (n = 36), American (n = 29) and African (n = 28) associations. Two thirds of respondents were of the level of a consultant/attending neurosurgeon (66.1%), 27.6% were neurosurgery trainees, and a few general surgeons, general practitioners, or other providers of neurosurgery participated. When asked if neurosurgical training was available in their country, 16.2% indicated that it was not. Regarding place of practice, most of the neurosurgical care was provided in the public hospital setting (67.6%), although 30.5% of time was in the private sector, and 2.9% in faith-based hospitals; 92.9% of participants practiced in urban settings.

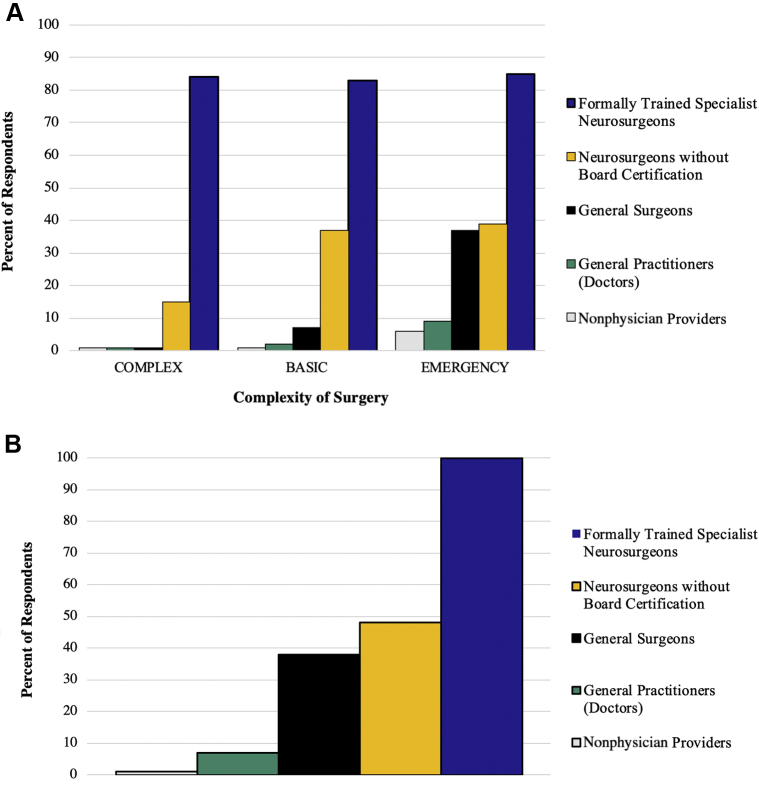

The level of reported neurosurgical providers by country is shown in Figure 4A and B. Figure 4A shows which level of provider performs neurosurgery at the country level, and Figure 4B shows the reported complexity of surgeries performed according to provider level. Overall, 95.1% of respondents (n = 103) reported that they had formally trained specialist neurosurgeons in their country (1 individual from the countries of Bangladesh, DRC, Egypt, Kenya, and Turkey responded “no”; this is discussed in the Limitations section). A total of 20 of the 47 responding countries (42.6%) indicated that TS/S was ongoing in their respective countries. When asked about individuals who completed a neurosurgical training program who are not board-certified consultants/attendings but practice as a neurosurgeon, 44 of 102 respondents from 18 countries affirmed (Brazil, DRC, Egypt, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Morocco, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Vietnam). Thirty-nine of 103 respondents stated that general surgeons performed neurosurgery in their respective country (Belarus, Cameroon, DRC, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, and Zimbabwe; 17 countries). Six of 104 respondents stated that general practitioners performed neurosurgery in their respective country (Malawi, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, Sudan, and Tanzania; 6 countries). Malawi and Morocco reported that nonphysician providers also performed neurosurgical procedures. The specific types of procedures that TS/S providers reportedly performed is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Complexity of procedures performed by neurosurgeons and task-shifting and task-sharing providers. (A) Who performs neurosurgery at the country level. (B) The reported complexity of surgeries performed according to provider level. The x-axis reflects the number of responses.

Figure 5.

Types of procedures performed by task-shifting and task-sharing providers.

Details from the 20 described TS/S programs are outlined in Table 2. When asked if the Ministry of Health (MOH) endorsed TS/S, 99 individuals responded; 63.6% replied no, 11.1% replied yes (Cameroon, DRC, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Malawi, Malaysia, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Turkey), and 25.3% were unsure. Some countries with multiple respondents had both yes and no answers from their respective country, denoting a potential misunderstanding or uncertainty of the MOH's endorsement of TS/S. The statement by the respective MOH in each country was not verified during this study. Of these 99 respondents, 8.0% stated that there was a standardized training program for TS/S providers in neurosurgery. When asked about the typical duration of training in years for uncertified neurosurgery providers, quantitative answers ranged from no training beyond a general surgery residency to 1 month (Ethiopia, Indonesia), 3 months (Malaysia, Morocco, Nigeria, Thailand, Philippines), 6 months (Sri Lanka), and 2–3 years (Pakistan).

Table 2.

Details of Task-Shifting and Task-Sharing Training Programs Where Respondents Noted that Neurosurgical Task-Shifting and Task-Sharing Was Occurring in Their Respective Countries

| Country | TS/S Provider Type | Ministry of Health Endorsed (Subjective) | Standardized Training | Length of Training Required | Location of Training | Method of Training | Who Leads Training | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarus | GS | Unsure | No | –— | — | — | — | — |

| Cameroon | GS | Yes | No | — | — | — | — | — |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | GS | No | No | Not standardized | Not standardized | Not standardized | NS | They have to seek permission from consultants for every operation |

| Egypt | Not available | Yes | No | 2–3 years | Referral hospitals | Clinical experience | Minimal cases/emergencies can be performed by uncertified NS | |

| Ethiopia | GS | Yes | No | 1 month; 3 months | Teaching hospital | Clinical experience; assist emergency surgery | NS | They perform the surgeries in district hospitals and/or where NS are unavailable, and when patients are unable to be referred because of financial reasons or rapid deterioration |

| India | GS | No/Unsure | No | Unstructured not allowed | — | — | — | TS/S is variable, practiced in few institutions, or in rural practice. Not regulated. It depends on the senior neurosurgical consultant covering the region |

| Indonesia | GS | Yes | Yes | 1–2 months | NS unit, all centers | Part of general surgery training | NS | General surgeons have autonomy to perform emergency neurosurgery such as burr-hole evacuation of epidural hematoma in remote areas in which referral to neurosurgeons is time consuming or impossible |

| Kenya | GS | No | No | — | — | — | — | — |

| Malawi | GP, NPP | Yes | No | — | — | — | — | A neurosurgeon is not always available to supervise them but they are encouraged to consult if in any case they are in doubt or it is beyond their scope of training or experience. All complicated cases within their scope must be referred. All cases outside their scope must be referred |

| Malaysia | GS | Yes | Yes | 3 months | NS center | Part of general surgery training | NS | No formal training program available, GS must obtain endorsement by the head of department in each hospital (for hospitals without NS) |

| Morocco | GS, GP, NPP | No | No | 3 months | France | Observation; clinical experience | NS | — |

| Namibia | GS, GP | Unsure | No | — | — | — | — | They perform burr-hole and ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Mostly alone (without supervision) |

| Nigeria | GS, GP | Yes | Yes | 3 months; trauma surgery training only | NS unit; trauma surgery | Observation/hands-on for highly motivated; part of GS training | NS; trauma surgeons | No task shifting, but task sharing practiced and encouraged, mostly in rural areas with no NS supervision. Only resuscitate, then refer to NS. Such providers do personally refer patients they are unable to handle or with resultant complications from their procedures to trained NS |

| Pakistan | GS | No | No | 2 years | Postgraduate medical institute | Local curriculum authorities | — | TS/S is practiced in teaching hospitals with cover and in private practice groups. I know of those who have almost completed their training but unfortunately could not clear their exit exams [but still perform NS] |

| Philippines | GS | No | No | 3 months | Government teaching hospital | Direct supervision on rotation | NS | Basic emergency trauma procedures that are lifesaving for exigency purposes |

| Sri Lanka | GS | Yes | No | 6 months | Same hospital as GS training | Clinical experience | NS | — |

| Sudan | GS, GP | No | Yes (only for board-certified NS) | TS/S training unclear | — | — | — | Traditionally refer to advance NS trauma center. TS/S not allowed apart from burr hole in remote area for lifesaving surgery. We have a specialized local board (for clinical approval) |

| Tanzania | GS, GP | Unsure | No | Not specified | Local hospital | Assist in surgery | — | Training of uncertified neurosurgeons happens accidentally/not planned. When one meets an interested trainee, it occurs briefly and unsupervised. No one is sure whether the actual neurosurgery practice continues after the training |

| Thailand | GS | Unsure | Yes | 3 months | University hospital | — | NS | — |

| Zimbabwe | GS | No | No | — | — | — | — | — |

TS/S, task-shifting and task-sharing; GS, general surgeon; NS, specialist neurosurgeon; GP, general practitioner; NPP, nonphysician provider.

A subset of respondents elaborated in free text response, which can be viewed in the far-right column in Table 2. General themes involved permitting TS/S in neurosurgery in the setting of an emergency, such as an epidural hematoma evacuation, when a fully trained neurosurgeon was not available. One Ethiopian respondent noted:

They [General Surgeons] do the surgeries where there are no neurosurgeons, and patients are unable to be referred due to financial reasons or because the patient is deteriorating fast.

Another Ethiopian affirmed this observation:

They [General Surgeons] practice in district hospitals where virtually no neurosurgeons are available.

In Indonesia:

General surgeons have autonomy to perform emergency neurosurgery such as burr-hole evacuation of EDH [epidural hematoma] in remote areas where referral to neurosurgeons is time consuming or impossible.

A Sudanese individual noted that TS/S is “not allowed, apart [from a] burr hole in [a] remote area for life saving.” In Cape Verde, there was no report on ongoing TS/S, but 1 respondent noted:

[We have] only one neurosurgeon from Cuba cooperation since 2015. Before that, general surgeons performed emergency neurosurgery and complex cases were sent to Portugal.

When remuneration for TS/S providers was discussed, 40.9% replied that TS/S providers received no financial payment for neurosurgical procedures, 55.2% were unsure (or not applicable), and 3.2% replied in the affirmative (n = 93; countries recognizing remuneration for TS/S were Indonesia, Kenya, and Turkey). The ability for TS/S providers to continue medical education or maintenance of certification throughout their training was recognized by 9.8% (n = 92; 41.3%, no; 48.9% unsure/not applicable). Continued professional development opportunities for TS/S providers were reported by 8.6% (n = 93; 40.9%, no; 50.5% unsure).

Discussion

This survey is the first cross-sectional examination of the global practice of TS/S care provision in neurosurgery. Its illumination of the prevalence of neurosurgical TS/S is an important step in describing the global neurosurgical workforce and discussing practical approaches to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 to mitigate the global burden of neurosurgical disease.20

Overall, 20 LMICs (42.6% of LMICs that responded) indicated that TS/S was ongoing in their country, which underscores the magnitude of the neurosurgeon workforce deficit and that many countries are seeking alternative methods for care provision. Although most TS/S models described used general surgeons, there were also reports of general practitioners and nonphysician providers performing neurosurgery. Perhaps more important was the lack of structure, oversight, and regulation for these TS/S models. Only 8 of the 20 countries that reported ongoing TS/S believed that this practice was endorsed by their government's MOH; data on the respective MOH's endorsements were not publicly available and verification would have involved interviewing the respective MOH offices, which was beyond the scope of this study but is being considered as a future research endeavor. In addition, only 4 countries stated there was a standardized TS/S training program. Most individuals reported that the training was led by a neurosurgeon, but it was unclear who conducted the teaching in many settings. There was tremendous variability in the length of time that TS/S providers trained (from 1 month to years) and there were no concrete examples of competency-based evaluation. Regarding the scope of TS/S provider practice, it seemed predominantly limited to emergency interventions in a rural or district setting, and the most common procedures were burr holes, craniotomy for hematoma evacuation, external ventricular drain, and shunts for hydrocephalus. However, more complex surgeries such as spinal fusion and tumor resection were also mentioned. By not having a defined scope of practice or a professional governing body for regulation, there is a serious risk of task-creep: practicing beyond the scope of one's training.4 The ability for TS/S providers to continue medical education throughout their training was recognized by only 9.8%, and remuneration, by only 3.2%.

Importantly, the survey illustrates the current landscape of neurosurgical TS/S and highlights opportune areas for system improvement. As long as there remains a gap between the demand for emergency neurosurgical care and provider capacity, TS/S is likely to arise. Ethically, TS/S presents many challenges. On one hand, having a necessary operation via TS/S may be superior to no care at all; TS/S may allow acute stabilization of emergency patients to enable safer transfer to tertiary-care facilities, thereby improving geographic and temporal access to more affordable, lifesaving therapies.13, 14 Conversely, TS/S raises concerns for lower-quality care, ambiguous informed consent because unprecedented surgical intervention models may include unknown risk, and disrupting professional roles if less-skilled workers replace higher-skilled staff, as has been discussed in the setting of nurse anesthetists and anesthesiologists.21 The core ethical principles of beneficence, respect for persons, and justice should remain central to the goal of care delivery, because it is our responsibility to maintain moral standards as we strive to meet workforce goals.22 However, these data call us to recognize that this process is ongoing, and we can take steps to improve safety.

To begin, task-sharing should be emphasized over task-shifting because shared clinical responsibility with expert involvement is presumed to be a safer option.4 Building from the theoretic model discussed in the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery and shown in Figure 1, it is first recommended that the TS/S trainee has obtained a degree in medicine and be in or have completed a surgical training program before beginning neurosurgical TS/S training. This strategy is to ensure adequate understanding of both medical and operative management and experience in clinical decision making. From the data, it seems that most country models already adhered to this practice, because 19 of the 21 countries identified general surgeons as TS/S providers; the 7 countries that reported general practitioner or nonphysician TS/S providers could adapt alternative training programs to ensure that only general surgeons were certified to perform such work. Regarding the training protocol, there would not have to be a one-size-fits-all model, but local and tertiary-care hospitals could work with their national neurosurgical society and MOH to agree on defining the details of their training programs. Countries that recognized specific lengths of neurosurgical TS/S training included ranges from 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, to multiple years, and there was variation between observation and operative exposure. For individuals to be competent and confident in technical and nontechnical skills, observation is unlikely to be sufficient, and the length of training should correlate with a set number of supervised operative experiences. Furthermore, the programs should involve competency-based evaluation before allowing TS/S providers to practice. The direct link between surgical competence and learning curve progression and time, caseload experience, and graduated autonomy has been shown extensively in surgical education literature.17, 18, 23, 24 Local supervision should follow the completion of formal training to ensure maintenance of skills and competencies. Subsequently, local supervision should happen periodically to ensure maintenance of skills and competencies, and proper referral networks should be established for complex cases and complications to allow for teleconsultation and physical transfer of patients when necessary.19

The governance and financing of TS/S regulation and maintenance are critical. Again, only 8 of the 20 countries who reported ongoing TS/S believed that this practice was endorsed by their government's MOH. The importance of governmental support can be shown with the Mozambique model of Tecnicos de cirurgia. In 1984, the Mozambican health system introduced Tecnicos de cirurgia as a new professional cadre to deliver basic comprehensive services, mainly in rural areas.25 Initially, this effort was met with resistance from medical doctors and nurses. However, by having a governance structure, the health system was able to regulate training, define a scope of practice, collect data for ongoing evaluation and safety improvement, and provide financial compensation that facilitated workforce retention.26 If neurosurgical TS/S providers were officially recognized and supported by their MOH and institutions with a clear definition of their scope of practice adequate financial remuneration, and clear opportunities for career progression, it could prevent task-creep to protect both the patients and the providers. Clear role definition empowers the TS/S provider to defer operations that they may be pressured to perform electively and protect patients from being taken advantage of by individuals seeking to expand their skill set unsafely for financial or professional gains.4 It also mitigates worry from other professional roles about job security and encroachment upon their specialty. These data show that clear role definition is needed, because it would be more advisable that complex procedures such as spinal fusion and tumor resection remain under the practice of fully trained neurosurgeons.

Limitations

The limitations of this study warrant further discussion. The absolute prevalence of TS/S practice should be interpreted with caution, because we used neurosurgical member societies as our primary source of survey dispersal, and the individuals who received the survey though neurosurgical society e-mail lists were mostly practicing neurosurgeons in urban settings. These individuals may have limited information about nonneurosurgeon providers and ongoing practices in rural or remote parts of the country, or there may be political reasons or bias that lead to underreporting. However, that situation would likely underestimate the true prevalence of TS/S, making this a conservative estimate. Regarding survey structure, questions may have been misinterpreted or the individual who completed the survey may not have had accurate information. An example of this was potential misinterpretation of the number of “formally trained” specialist neurosurgeons in one's country, because 5 individuals from Bangladesh, DRC, Egypt, Kenya, and Turkey reported zero; however, we know from the 2016 World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies survey that these countries have approximately 138, 4, 400, 22, and 981 neurosurgeons, respectively.27 This incongruence likely reflects national differences in the qualifications and definitions of “formally trained specialist neurosurgeons” rather than inaccurate reporting, but it should be considered during data interpretation. Nonetheless, this study represents one of the first attempts to elucidate global perspectives on TS/S in neurosurgery and will facilitate further discussion on workforce solutions.

Conclusions

The combination of neurosurgical workforce deficits and a high and increasing burden of neurologic trauma and disease amplifies the demand for scaling up neurosurgical care in low-resource settings. This survey shows that TS/S is ongoing in many LMICs without substantial structure or oversight, which is concerning for patient safety. Overall, this survey represents a call to action for future discussions on policy and training programs. Additional recommendations and regulations could increase the level of care, such as additional governance, requiring standardized training, competency-based evaluation, clear role definition, maintenance of certification, adequate oversight, and proper referral networks for complex cases. Moreover, continued collaboration between high-income countries and LMICs is needed to optimize residency and task-sharing training programs, ensure proper governance and financing of task-sharing models, and encourage an iterative reflection and improvement process as we strive to mitigate the global burden of neurosurgical disease by 2030.

Declaration of Competing Interest

A.G.K. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma. The Group was commissioned by the NIHR using Official Development Assistance funding (project 16/137/105). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the United Kingdom National Health Service, NIHR, or the United Kingdom Department of Health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge those who served as expert consultants for survey creation (in addition to those who were coauthors in the writing of the article): Jeffrey Rosenfeld, Naci Balak, Ahmed Ammar, Magnus Tisel, Michael Haglund, Timothy Smith, Ivar Mendez, Jannick Brennum, Stephen Honeybul, Akira Matsumara, Severien Muneza, Andres Rubiano, Gail Rosseau, Tariq Khan, Basant Misra, Gene Bolles, David Adelson, Robert Dempsey, and Peter Hutchinson.

Footnotes

Marike L.D. Broekman and Kee B. Park are co-senior authors.

Contributor Information

Faith C. Robertson, Email: frobertson@partners.org.

Collaborative Working Group:

Jeffrey Rosenfeld, Naci Balak, Ahmed Ammar, Magnus Tisel, Michael Haglund, Timothy Smith, Ivar Mendez, Jannick Brennum, Stephen Honeybul, Akira Matsumara, Severien Muneza, Andres Rubiano, Gail Rosseau, Tariq Khan, Basant Misra, Gene Bolles, David Adelson, Robert Dempsey, Peter Hutchinson, Abenezer Aklilu, Abigail Javier-Lizan, Adil Belhachmi, Ahtesham Khizar, Alexandru Tascu, Ali Yalcinkaya, Aliyu Baba Ndajiwo, Alvan-Emeka Ukacjukwu, Amit Agrawal, Amit Thapa, Ana C.V. Silva, Armin Gretschel, Arvind Sukumaran, Atul Vats, Bakr Abo Jarad, Balgopal Karmacharya, Bipin Chaurasia, Boon Seng Liew, Carlos A. Rodriguez Arias, Claire Karekezi, Cohen-Inbar Or, Danjuma Sale, Davendran Kanesen, Djula Djilvesi, Evarsitus Nwaribe, M. Elhaj Mahmoud, Mian Awais, Sanjay Kumar, Amos O. Adeleye, Manish Agarwal, Menelas Nkeshimana, Sunday David Ndubuisi Achebe, Walid El Gaddafi, Ece Uysal, Eghosa Morgan, Elubabor Buno, Emmanuel Sunday, Esayas Adefris, Fayez Alelyani, Felipe Constanzo, Gabriel Longo, Ghulam Farooq, Goertz Mirenge Dunia, Gyang Markus Bot, Hamisi K. Shabani, Harch Deora, Hassan Almenshawy, Hazem Kuheil, Igor Lima Maldonado, Ionut Negoi, Irfan Yousaf, Jafri Malin Abdullah, Jagos Golubovic, Khalil Ayadi, Kriengsak Limpastan, Luxwell Jokonya, Mirsad Hodzic, Mohamed Kassem, Mohammed Al-Rawi, Muhammad Tariq, Mykola Vyval, Naci Balak, Nidal Abuhadrous, Nikolaos Syrmos, Osaid Alser, Paul H. Young, Petra Wahjoepramono, Prabu Rau Sriram, Rafik Ouchetati, Recep Basaran, Ritesh Bhoot, Robson Amorim, Rosanda Ilić, Saman Wadanamby, Samuel M. Fetene, Sanjay Behari, Satish Babu, Tariq Khan, Trung Kien Duong, Tsegazeab Laeke, Ulrick S. Kanmounye, Vladimir Komar, Ipe Vazheeparambil George, Zahid Hussain, Lynne Lourdes N. Lucena, Hugues Brieux Ekouele Mbaki, Ken-Keller Kumwenda, Djvnaba Bah, Ibrahim E. Efe, Dickson Bandoh, Yunus Kuntawi Aji, and Thomas Dakurah

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Burton A. Training non-physicians as neurosurgeons in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:684–685. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartelme T. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 2017. A Surgeon in the Village: An American Doctor Teaches Brain Surgery in Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Task Shifting: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meara J.G., Leather A.J., Hagander L. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Surgery. 2015;158:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullan F., Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2007;370:2158–2163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu K., Rosseel P., Gielis P., Ford N. Surgical task shifting in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashengo T., Skeels A., Hurwitz E.J.H., Thuo E., Sanghvi H. Bridging the human resource gap in surgical and anesthesia care in low-resource countries: a review of the task sharing literature. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:77. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewan M.C., Rattani A., Gupta S. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. [e-pub ahead of print] J Neurosurg. 2018 doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352 accessed April 10, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock C.N., Donkor P., Gawande A., Jamison D.T., Kruk M.E., Debas H.T. Essential surgery: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2015;385:2209–2219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewan M.C., Rattani A., Fieggen G. Global neurosurgery: the current capacity and deficit in the provision of essential neurosurgical care. Executive Summary of the Global Neurosurgery Initiative at the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. [e-pub ahead of print] https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.11.JNS171500 accessed April 10, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tyson A.F., Msiska N., Kiser M. Delivery of operative pediatric surgical care by physicians and non-physician clinicians in Malawi. Int J Surg. 2014;12:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao T.E., Patel P.B., Kikubaire M., Niescierenko M., Hagander L., Meara J.G. Surgical care in Liberia and implications for capacity building. World J Surg. 2015;39:2140–2146. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson F., Briones R., Baticulon R., Leather A., Gormley W., Lucena L. King’s College; London: 2018. Is task-sharing a safe solution to the neurosurgery workforce deficit? A retrospective cohort study in the Philippines. MSc Thesis, Global Health with Global Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luck T., Treacy P.J., Mathieson M., Sandilands J., Weidlich S., Read D. Emergency neurosurgery in Darwin: still the generalist surgeons' responsibility. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:610–614. doi: 10.1111/ans.13138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCampbell C., Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi Method to the use of experts. Management Science. 1993;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Bank New country classifications by income level: 2018-2019. 2018. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2018-2019 Available at: Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 17.Law C., Hong J., Storey D., Young C.J. General surgery primary operator rates: a guide to achieving future competency. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:997–1000. doi: 10.1111/ans.14121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pernar L.I.M., Robertson F.C., Tavakkoli A., Sheu E.G., Brooks D.C., Smink D.S. An appraisal of the learning curve in robotic general surgery. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4583–4596. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orton M., Agarwal S., Muhoza P. Strengthening delivery of health services using digital devices. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(suppl 1):S61–S71. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barthelemy E.J., Park K.B., Johnson W. Neurosurgery and sustainable development goals. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radzvin L.C. Moral distress in certified registered nurse anesthetists: implications for nursing practice. AANA J. 2011;79:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Belmont Report Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. J Am Coll Dent. 2014;81:4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown C., Abdelrahman T., Patel N., Thomas C., Pollitt M.J., Lewis W.G. Operative learning curve trajectory in a cohort of surgical trainees. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1405–1411. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougherty P.J., Cannada L.K., Murray P., Osborn P.M. Progressive autonomy in the era of increased supervision: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:e122. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Luz Vaz M., Bergstrom S. Mozambique–delegation of responsibility in the area of maternal care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1992;38(suppl):S37–S39. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(92)90028-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cumbi A., Pereira C., Malalane R. Major surgery delegation to mid-level health practitioners in Mozambique: health professionals' perceptions. Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies World Neurosurgery Workforce Map. 2016. https://www.wfns.org/menu/61/global-neurosurgical-workforce-map Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.