Mitral valve surgery remains the standard of care for the vast majority of patients with mitral valve pathology. Surgical mitral valve repair of primary degenerative mitral regurgitation (DMR) in particular has excellent long-term outcomes with very low operative mortality and morbidity in the hands of experienced cardiac surgeons (1,2). In this edition of the journal Liu and colleagues present a larger series of mitral valve replacement comparing outcomes between a minimally-invasive and standard median sternotomy approach (3). From over a thousand patients undergoing mitral valve replacement (± tricuspid valve or atrial fibrillation ablation) in a 3-year period, almost 40% had their valve replaced using a minimally-invasive cardiac surgery (MICS) technique via right thoracotomy. With well over 300 mitral valve replacement cases per year, this study comes from a high-volume center with significant experience. The etiology requiring surgery is not stated in the manuscript, but given the larger number of mitral valve replacement rather than repair, it is likely that rheumatic mitral valve disease represents the most prevalent pathology. Rheumatic mitral valve pathology has been almost completely eliminated in Northern America and Western Europe but continues to pose a substantial public health problem in Asia (4). Compared to primary DMR resulting from leaflet prolapse, it often presents as a complex substrate for mitral valve repair. Mitral valve replacement then is a much easier procedure from a technical perspective. From the entire cohort of patients receiving a mitral valve replacement, the authors created 404 matched pairs (minimally-invasive versus sternotomy) to reduce the risk of confounding-by-indication. They conclude that in spite of somewhat longer cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamps and total procedure times in the MICS group, patients in both groups have similar outcomes in terms of mortality and morbidity including stroke and renal failure. They also report lower transfusion rates, shorter ventilation times and ICU length-of-stay as well as a shorter index hospitalization in the MICS group. Importantly, they highlight a faster recovery in the MICS group as measured by the time to return to work or study. The authors are to be congratulated on a large series with good short-term outcomes at a mean follow up of 26 months. These outcomes are consistent with previous research about the safety and effectiveness of MICS mitral valve surgery (5-9).

Some information of particular interest in the current era is not presented in the manuscript, such as the mean gradient across the new valve immediately postoperatively and at follow up, the incidence of paravalvular leaks or structural valve deterioration, and the reasons for re-intervention. This kind of information is increasing in importance as transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) is being researched extensively. While studies investigating the safety and effectiveness of TMVR are ongoing, the technology will continue to evolve rapidly and become an alternative to open surgical mitral valve replacement.

In their study Liu et al. do also not provide details about surgeons and their experience with MICS or whether the same surgeons performed both sternotomy and minimally-invasive cases. This is a common point of contention with comparative studies like the one presented here. Because minimally-invasive valve surgery is technically more demanding and has a unique learning curve, it would be preferable to have contemporary cases and controls that were performed by the same surgeon. However, that is often not a realistic scenario and most commonly results in a bias favoring MICS when the comparison does not factor in surgeon experience and technical skills, both of which are known to correlate with outcomes (10). Based on current evidence it should be stated that valve surgery in general, and minimally-invasive valve surgery in particular, probably yields the best results when performed by experienced surgeons at higher volume centers. This is not entirely surprising, and common sense would dictate that more experience translates into better results. From a public health perspective, the more pressing question seems to be how we can standardize the approach to surgical mitral valve repair and replacement, invest in a subspecialized work-force with expertise in mitral valve surgery, so to ensure all patients have access to high-quality mitral valve surgery.

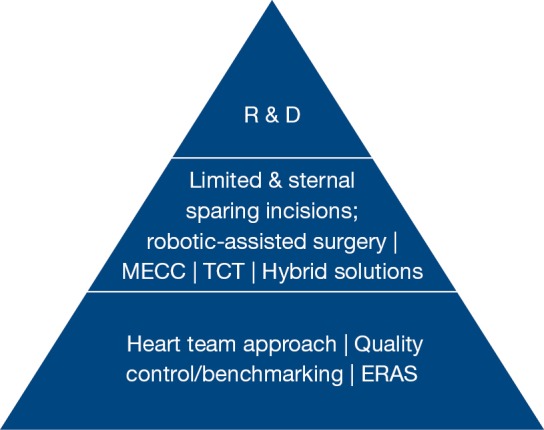

With the advent of transcatheter technology as the ultimate minimally-invasive strategy, there has certainly been a growing interest in MICS by both surgeons and patients alike. More surgeons than ever now offer some form of minimally-invasive surgery. At the same time, it is quite clear that the scrutiny of outcomes with surgical valve repair and replacement has entered a new era because of the availability and successes of transcatheter technology. For patients, the safety and quality of a surgical valve repair or replacement remain the most important outcomes and therefore must never be jeopardized for a less-invasive approach. Simultaneously, the concept of MICS has to extend beyond simply smaller incision (minimal-access surgery). A contemporary MICS program should encompass several other aspects including evaluation by a multidisciplinary heart team, an enhanced recovery after surgery program (ERAS), optimization of the cardiopulmonary bypass machine to reduce its impact, transcatheter technology and hybrid solutions (e.g., trans-atrial placement of a transcatheter heart valve in the mitral position) (Figure 1). In fact, these components play a major role in allowing patients to have a quicker recovery, and in combination with smaller, sternal-sparing incisions will make valve surgery a better alternative or complement to transcatheter technology (11). As is true with surgery using a traditional, not minimally-invasive approach, optimizing all phases (pre-, intra-, postoperative) and aspects of care (surgical and non-surgical) will ultimately result in best outcomes and most expedient recovery from what remains a major impact on the body in spite of being labeled minimally-invasive.

Figure 1.

Components of a contemporary minimally-invasive valve surgery program. ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery program; MECC, miniaturized extracorporeal circulation/cardiopulmonary bypass; TCT, transcatheter technology; R&D, research and development (e.g., new devices, off-label use).

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Editorial Office, Annals of Translational Medicine. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Gammie JS, Chikwe J, Badhwar V, et al. Isolated Mitral Valve Surgery: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:716-27. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.03.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakaeen FG, Shroyer AL, Zenati MA, et al. Mitral valve surgery in the US Veterans Administration health system: 10-year outcomes and trends. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:105-17.e5. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.07.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Chen B, Zhang YY, et al. Mitral valve replacement via minimally invasive totally thoracoscopic surgery versus traditional median sternotomy: a propensity score matched comparative study. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:341. 10.21037/atm.2019.07.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iung B, Vahanian A. Epidemiology of acquired valvular heart disease. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:962-70. 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iribarne A, Easterwood R, Russo MJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive versus traditional sternotomy mitral valve surgery in elderly patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:S86-90. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iribarne A, Russo MJ, Easterwood R, et al. Minimally invasive versus sternotomy approach for mitral valve surgery: a propensity analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:1471-7; discussion 1477-8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iribarne A, Easterwood R, Chan EY, et al. The golden age of minimally invasive cardiothoracic surgery: current and future perspectives. Future Cardiol 2011;7:333-46. 10.2217/fca.11.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iribarne A, Easterwood R, Russo MJ, et al. A minimally invasive approach is more cost-effective than a traditional sternotomy approach for mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:1507-14. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.04.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modi P, Hassan A, Chitwood WR, Jr. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:943-52. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onnasch JF, Schneider F, Falk V, et al. Five years of less invasive mitral valve surgery: from experimental to routine approach. Heart Surg Forum 2002;5:132-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelman DT, Ben Ali W, Williams JB, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Cardiac Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society Recommendations. JAMA Surg 2019;154:755-66. 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]