To the Editor,

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory and systemic illness that may progress to severe hypoxemia needing some form of ventilatory support in as many as 15–20% of suspected and confirmed cases [1]. In outbreak regions, the surge in critically ill patients has placed significant strain on intensive care units (ICUs), with volume demands that overwhelm current capacity [1]. There is a compelling need to identify clinical predictors of severe COVID-19 to enable risk stratification and optimize resource allocation.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [2]. Alterations in local/systemic inflammatory response, impaired host immunity, microbiome imbalance, persistent mucus production, structural damage, and use of inhaled corticosteroids have been hypothesized to contribute to such risk [3]. With respect to COVID-19, levels of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the reported host receptor of the virus responsible of COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SARS-CoV-2), have been observed to be increased in patients with COPD [4,5]. However, early individual COVID-19 studies have not consistently reported a significantly higher rate of severe disease in COPD patients [6,7]. In this article, we analyze if COPD may be associated with increased odds of severe COVID-19 infection.

An electronic search was performed in Medline (PubMed interface), Scopus and Web of Science, using the keywords “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” OR “COPD” OR “clinical characteristics” AND “coronavirus 2019” OR “COVID-19” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2”, between 2019 and present time (i.e., March 9, 2020). No language restrictions were applied. The title, abstract and full text of all articles captured with the search criteria were evaluated, and those reporting the rate of COPD in COVID-19 patients with a clinically validated definition of severe disease were included in this meta-analysis. The reference list of all identified studies was also analyzed (forward and backward citation tracking) to detect additional articles.

The obtained data was pooled into a meta-analysis, with estimation of the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) in patients with or without severe forms of COVID-19. The statistical analysis was performed using MetaXL, software Version 5.3 (EpiGear International Pty Ltd., Sunrise Beach, Australia). The study was carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and with the term of local legislation.

Overall, 87 articles were initially identified based on our electronic and reference search, which after screening by tile, abstract, and full text, 80 were excluded as not related to COVID-19 (n = 27), were review articles (n = 7), did not provide relevant data (n = 28), were editorials (n = 10), did not provide data on severity or comorbidities (n = 5), compared patients by mortality not severity (n = 2) or compared mild cases to critical cases (n = 1). Thus, a total number of 7 studies were finally included in our meta-analysis, totaling 1592 COVID-19 patients, 314 of which (19.7%) had severe disease [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

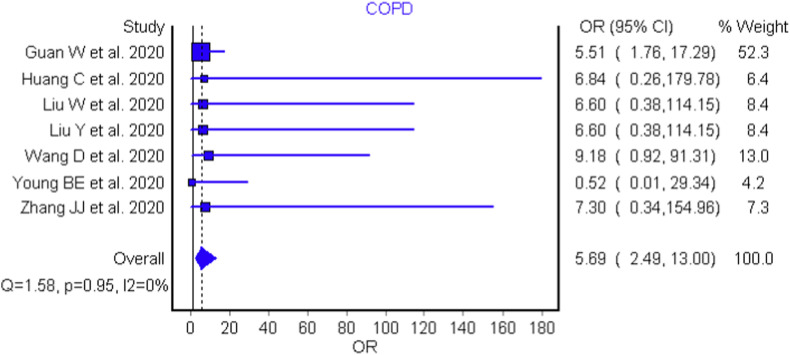

The essential characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 , whilst the individual and pooled OR of COPD for predicting severe COVID-19 is presented in Fig. 1 . Only in a single study was the individual OR found to be a significant predictor of COPD [8]. However, when the data of the individual studies was pooled, COPD was found to be significantly associated with severe COVID-19 (OR: 5.69 [95:CI: 2.49–13.00], I2 = 0.0%, Cochran's Q, p = 0.95). A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, excluding the largest study by Guan et al. [8] which accounted for 52.3% of pooled weight, found no significant differences (OR: 5.88 [95%CI: 1.78–19.50]).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Setting | Sample Size | Outcomes | Severe patients |

Non-severe patients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Age (yrs)a | Women (%) | n (%) | Age (yrs)a | Women (%) | ||||

| Guan W et al., 2020 | China | 1099 | Admission to ICU, MV, death | 173 (15.7%) | 52 (40–65) | 42% | 926 (84.3%) | 45 (34–57) | 42% |

| Huang C et al., 2020 | China | 41 | ICU Care | 13 (31.7%) | 49 (41–61) | 15% | 28 (68.3%) | 49 (41–58) | 32% |

| Liu W et al., 2020 | China | 78 | Admission to ICU, MV, Death | 11 (14.1%) | 66 (51–70) | 36% | 67 (85.9%) | 37 (32–41) | 52% |

| Liu Y et al., 2020 | China | 12 | Respiratory Failure, MV | 6 (50%) | 64 (63–65) | 50% | 6 (50.0%) | 44 (35–55) | 17% |

| Wang D et al., 2020 | China | 138 | Clinical Variables, MV, Death | 36 (26.1%) | 66 (57–78) | 39% | 102 (73.9%) | 51 (37–62) | 48% |

| Young BE et al., 2020 | Singapore | 18 | Treatment, ICU Care, Death | 6 (33.3%) | 56 (47–73) | 67% | 12 (66.6%) | 37 (31–56) | 42% |

| Zhang JJ et al., 2020 | China | 140 | Respiratory Distress/Insufficiency | 58 (41.4%) | 64 (25–87) | 43% | 82 (58.6%) | 52 (26–78) | 54% |

Age data presented as median (IQR). MV – Mechanical Ventilation, ICU – Intensive Care Unit.

Fig. 1.

Forest plot demonstrating association of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease with severe COVID-19 disease.

In conclusion, the results of this concise meta-analysis demonstrate COPD is associated with a significant, over five-fold increased risk of severe CODID-19 infection. Patients with a history of COPD should be encouraged adopt more restrictive measures for minimizing potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and contact with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19. Clinicians should also carefully monitor all COPD patients with suspected infection and, finally, it may be advisable to consider COPD as a variable in future risk stratification models.

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Qiu H., Tong Z., Ma P., Hu M., Peng Z., Wu W., Du B. China critical care clinical trials group (CCCCTG). Intensive care during the coronavirus epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05966-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Restrepo M.I., Mortensen E.M., Pugh J.A., Anzueto A. COPD is associated with increased mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2006;28:346–351. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00131905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Restrepo M.I., Sibila O., Anzueto A. Pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2018;81:187–197. doi: 10.4046/trd.2018.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. https://jvi.asm.org/content/early/2020/01/23/JVI.00127-20 [Internet] American Society for Microbiology Journals. [cited 2020 Mar 4]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toru Ü., Ayada C., Genç O., Sahin S., Arik Ö., Bulut I. Serum levels of RAAS components in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2015 https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/46/suppl_59/PA3970 [Internet] European Respiratory Society. [cited 2020 Mar 10]; 46Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W., Tao Z.-W., Lei W., Ming-Li Y., Kui L., Ling Z., Shuang W., Yan D., Jing L., Liu H.-G., Ming Y., Yi H. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin. Med. J. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-L., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L.-J., Zeng G., Yuen K.-Y., Chen R.-C., Tang C.-L., Wang T., Chen P.-Y., Xiang J., Li S.-Y., Wang J.-L., Liang Z.-J., Peng Y.-X., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.-H., Peng P., Wang J.-M., Liu J.-Y., Chen Z., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang C., Huang F., Wang F., Yuan J., Wang Z., Li J., Li J., Feng C., Zhang Z., Wang L., Peng L., Chen L., Qin Y., Zhao D., Tan S., Yin L., Xu J., Zhou C., Jiang C., Liu L. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., Zhao Y., Li Y., Wang X., Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2761044 [Internet] 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 8]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young B.E., Ong S.W.X., Kalimuddin S., Low J.G., Tan S.Y., Loh J., Ng O.-T., Marimuthu K., Ang L.W., Mak T.M., Lau S.K., Anderson D.E., Chan K.S., Tan T.Y., Ng T.Y., Cui L., Said Z., Kurupatham L., Chen M.I.-C., Chan M., Vasoo S., Wang L.-F., Tan B.H., Lin R.T.P., Lee V.J.M., Leo Y.-S., Lye D.C. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762688 [Internet] 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 8]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J.-J., Dong X., Cao Y.-Y., Yuan Y.-D., Yang Y.-B., Yan Y.-Q., Akdis C.A., Gao Y.-D. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. J. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]