Abstract

Background

Hip or knee replacement is a major surgical procedure that can be physically and psychologically stressful for patients. It is hypothesised that education before surgery reduces anxiety and enhances clinically important postoperative outcomes.

Objectives

To determine whether preoperative education in people undergoing total hip replacement or total knee replacement improves postoperative outcomes with respect to pain, function, health‐related quality of life, anxiety, length of hospital stay and the incidence of adverse events (e.g. deep vein thrombosis).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2013, Issue 5), MEDLINE (1966 to May 2013), EMBASE (1980 to May 2013), CINAHL (1982 to May 2013), PsycINFO (1872 to May 2013) and PEDro to July 2010. We handsearched the Australian Journal of Physiotherapy (1954 to 2009) and reviewed the reference lists of included trials and other relevant reviews.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised trials of preoperative education (verbal, written or audiovisual) delivered by a health professional within six weeks of surgery to people undergoing hip or knee replacement compared with usual care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We analysed dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios. We combined continuous outcomes using mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, we pooled data using a random‐effects meta‐analysis.

Main results

We included 18 trials (1463 participants) in the review. Thirteen trials involved people undergoing hip replacement, three involved people undergoing knee replacement and two included both people with hip and knee replacements. Only six trials reported using an adequate method of allocation concealment, and only two trials blinded participants. Few trials reported sufficient data to analyse the major outcomes of the review (pain, function, health‐related quality of life, global assessment, postoperative anxiety, total adverse events and re‐operation rate). There did not appear to be an effect of time on any outcome, so we chose to include only the latest time point available per outcome in the review.

In people undergoing hip replacement, preoperative education may not offer additional benefits over usual care. The mean postoperative anxiety score at six weeks with usual care was 32.16 on a 60‐point scale (lower score represents less anxiety) and was 2.28 points lower with preoperative education (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐5.68 to 1.12; 3 RCTs, 264 participants, low‐quality evidence), an absolute risk difference of ‐4% (95% CI ‐10% to 2%). The mean pain score up to three months postoperatively with usual care was 3.1 on a 10‐point scale (lower score represents less pain) and was 0.34 points lower with preoperative education (95% CI ‐0.94 to 0.26; 3 RCTs, 227 participants; low‐quality evidence), an absolute risk difference of ‐3% (95% CI ‐9% to 3%). The mean function score at 3 to 24 months postoperatively with usual care was 18.4 on a 68‐point scale (lower score represents better function) and was 4.84 points lower with preoperative education (95% CI ‐10.23 to 0.66; 4 RCTs, 177 participants; low‐quality evidence), an absolute risk difference of ‐7% (95% CI ‐15% to 1%). The number of people reporting adverse events, such as infection and deep vein thrombosis, did not differ between groups, but the effect estimates are uncertain due to very low quality evidence (23% (17/75) reported events with usual care versus 18% (14/75) with preoperative education; risk ratio (RR) 0.79; 95% CI 0.19 to 3.21; 2 RCTs, 150 participants). Health‐related quality of life, global assessment of treatment success and re‐operation rates were not reported.

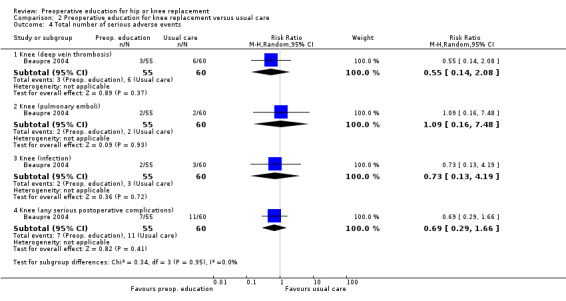

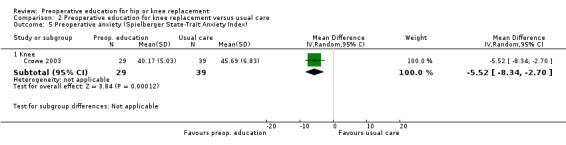

In people undergoing knee replacement, preoperative education may not offer additional benefits over usual care. The mean pain score at 12 months postoperatively with usual care was 80 on a 100‐point scale (lower score represents less pain) and was 2 points lower with preoperative education (95% CI ‐3.45 to 7.45; 1 RCT, 109 participants), an absolute risk difference of ‐2% (95% CI ‐4% to 8%). The mean function score at 12 months postoperatively with usual care was 77 on a 100‐point scale (lower score represents better function) and was no different with preoperative education (0; 95% CI ‐5.63 to 5.63; 1 RCT, 109 participants), an absolute risk difference of 0% (95% CI ‐6% to 6%). The mean health‐related quality of life score at 12 months postoperatively with usual care was 41 on a 100‐point scale (lower score represents worse quality of life) and was 3 points lower with preoperative education (95% CI ‐6.38 to 0.38; 1 RCT, 109 participants), an absolute risk difference of ‐3% (95% CI ‐6% to 1%). The number of people reporting adverse events, such as infection and deep vein thrombosis, did not differ between groups (18% (11/60) reported events with usual care versus 13% (7/55) with preoperative education; RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.66; 1 RCT, 115 participants), an absolute risk difference of ‐6% (‐19% to 8%). Global assessment of treatment success, postoperative anxiety and re‐operation rates were not reported.

Authors' conclusions

Although preoperative education is embedded in the consent process, we are unsure if it offers benefits over usual care in terms of reducing anxiety, or in surgical outcomes, such as pain, function and adverse events. Preoperative education may represent a useful adjunct, with low risk of undesirable effects, particularly in certain patients, for example people with depression, anxiety or unrealistic expectations, who may respond well to preoperative education that is stratified according to their physical, psychological and social need.

Keywords: Humans; Length of Stay; Patient Education as Topic; Anxiety; Anxiety/prevention & control; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip/adverse effects; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip/psychology; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Knee; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Knee/adverse effects; Arthroplasty, Replacement, Knee/psychology; Early Ambulation; Postoperative Complications; Postoperative Complications/psychology; Preoperative Care; Preoperative Care/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Preoperative education for hip or knee replacement

Background ‐ what is preoperative education?

Preoperative education refers to any educational intervention delivered before surgery that aims to improve people's knowledge, health behaviours and health outcomes. The content of preoperative education varies across settings, but frequently comprises discussion of presurgical procedures, the actual steps in the surgical procedure, postoperative care, potential stressful scenarios associated with surgery, potential surgical and non‐surgical complications, postoperative pain management and movements to avoid post‐surgery. Education is often provided by physiotherapists, nurses or members of multidisciplinary teams, including psychologists. The format of education ranges from one‐to‐one verbal communication, patient group sessions, or video or booklet with no verbal communication.

Study characteristics

This summary of a Cochrane review presents what we know from research on whether preoperative education improves outcomes (e.g. pain, function) compared with usual care in people receiving hip or knee replacement. After searching for all relevant studies to May 2013, we included nine new studies since the last review, giving a total of 18 studies (1463 participants); 13 trials included 1074 people (73% of the total) undergoing hip replacement, three involved people undergoing knee replacement and two included both people with hip and knee replacements. Most participants were women (59%) and the mean age of participants was within the range of 58 to 73 years

Key results ‐ what happens to people who have preoperative education compared with people who have usual care for hip replacement

Postoperative anxiety (lower scores mean less anxiety):

People with hip replacement who had preoperative education had postoperative anxiety at six weeks that was 2.28 points lower (ranging from 5.68 points lower to 1.12 points higher) (4% absolute improvement, ranging from 10% improvement to 2% worsening). ‐ People who had usual care for hip replacement rated their postoperative anxiety score as 32.16 points on a scale of 20 to 80 points.

Pain (lower scores mean less pain):

People with hip replacement who had preoperative education had pain at up to three months that was 0.34 points lower (ranging from 0.94 points lower to 0.26 points higher) (3% absolute improvement, ranging from 9% improvement to 3% worsening). ‐ People who had usual care for hip replacement rated their pain score as 3.1 points on a scale of 0 to 10 points.

Function (lower scores mean better function or less disability):

People with hip replacement who had preoperative education had function at 3 to 24 months that was 4.84 points lower (ranging from 10.23 points lower to 0.66 points higher) (7% absolute improvement, ranging from 15% improvement to 1% worsening). ‐ People who had usual care for hip replacement rated their function score as 18.4 points on a scale of 0 to 68 points.

Side effects:

About 5 fewer people out of 100 had adverse events (such as infection or deep vein thrombosis) with preoperative education compared with usual care but this estimate is uncertain. ‐ 18 out of 100 people reported adverse events with preoperative education for hip replacement. ‐ 23 out of 100 people reported adverse events with usual care for hip replacement.

Quality of the evidence

This review shows that in people receiving hip or knee replacement who are provided with preoperative education:

There is low‐quality evidence suggesting that preoperative education may not improve pain, function, health‐related quality of life and postoperative anxiety any more than usual care. Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in these estimates and is likely to change the estimates.

Health‐related quality of life, global assessment of treatment success and re‐operation rates were not reported.

We are uncertain whether preoperative education results in any fewer adverse events, such as infection or deep vein thrombosis, compared with usual care, due to the very low quality evidence.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Preoperative education versus usual care for hip replacement.

| Preoperative education versus usual care for hip replacement | ||||||

| Patient or population: hip replacement Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: preoperative education versus usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Preoperative education versus usual care | |||||

| Pain Visual analogue scale. Scale from: 0 to 10 (lower scores indicate less pain). Follow‐up: up to 3 months | The mean pain in the control groups was 3.11 | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 0.34 lower (0.94 lower to 0.26 higher)2 | ‐ | 227 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low3,4 | Absolute risk difference ‐3% (95% CI ‐9% to 3%); relative per cent change ‐11% (95% CI ‐30% to 8%). NNTB NA SMD ‐0.17 (95% CI ‐0.47 to 0.13) |

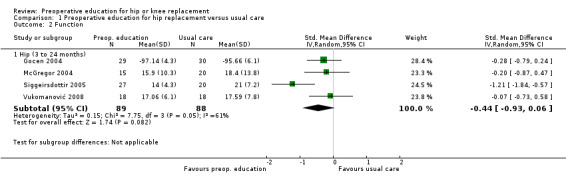

| Function WOMAC function (Likert scale version). Scale from: 0 to 68 (lower scores indicate better function). Follow‐up: from 3 to 24 months | The mean function in the control groups was 18.45 | The mean function in the intervention groups was 4.84 lower (10.23 lower to 0.66 higher)6 | ‐ | 177 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low3,4 | Absolute risk difference ‐7% (95% CI ‐15% to 1%); relative per cent change ‐26% (95% CI ‐56% to 4%). NNTB NA SMD ‐0.44 (95% CI ‐0.93 to 0.06). |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | 2 trials reported measuring health‐related quality of life using the Nottingham Health Profile, but neither reported data suitable for analysis. |

| Global assessment of treatment success | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No trial reported measuring global assessment of treatment success. |

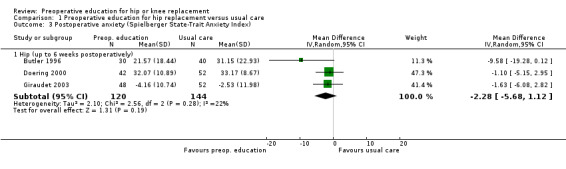

| Postoperative anxiety Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Index. Scale from: 20 to 80 (lower scores indicated less anxiety). Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | The mean postoperative anxiety in the control groups was 32.167 | The mean postoperative anxiety in the intervention groups was 2.28 lower (5.68 lower to 1.12 higher) | ‐ | 264 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,8 | Absolute risk difference ‐4% (95% CI ‐10% to 2%); relative per cent change ‐7% (95% CI ‐18% to 4%). |

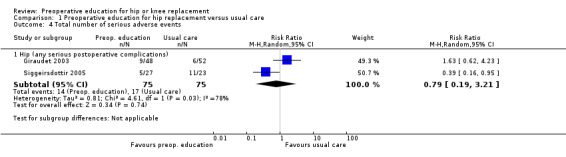

| Total number of serious adverse events (infection, thrombosis, other serious adverse events) | Study population | RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.19 to 3.21) | 150 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,9 | Absolute risk difference ‐10% fewer adverse events with preoperative education (‐46% fewer to 27% more); relative per cent change ‐21% (95% CI ‐81% to 221%). | |

| 227 per 1000 | 179 per 1000 (43 to 728) | |||||

| Re‐operation rate | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No trial reported measuring re‐operation rate. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NA: not available; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean visual analogue scale (VAS) (0‐10) pain score at 3 months in the usual care group reported in McGregor 2004 was used as the assumed control group risk.

2 To convert SMD to mean difference (MD), the pooled baseline standard deviation (SD) in McGregor 2004 (SD = 2) was multiplied by the SMDs and 95% CIs to convert values to a 0‐ to 10‐point VAS.

3 In all but 1 randomised controlled trial, allocation concealment was unclear, and no trial blinded participants. 4 95% CIs of the MD are wide. 5 Mean WOMAC function score at 3 months in the usual care group reported in McGregor 2004 was used as the assumed control group risk.

6 To convert SMD to MD, the pooled baseline SD in McGregor 2004 (SD = 11) was multiplied by the SMDs and 95% CIs to convert values to the 0‐ to 68‐point WOMAC function (Likert scale version) score.

7 Control group mean calculated as the mean of Butler 1996 and Doering 2000 (which both reported end of treatment values; Giraudet 2003 was excluded from this estimation as only change scores were reported).

8 Only 1 of the 3 included RCTs had unclear allocation concealment (the remaining 2 RCTs had clear allocation concealment), though no RCT blinded participants.

9 Heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 85%).

Summary of findings 2. Preoperative education versus usual care for knee replacement.

| Preoperative education versus usual care for knee replacement | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with knee replacement Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: preoperative education versus usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Preoperative education versus usual care | |||||

| Pain WOMAC pain. Scale from: 0 to 100 (lower scores indicate less pain). Follow‐up: mean 12 months | The mean pain in the control groups was 80 | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 2 higher (3.45 lower to 7.45 higher) | ‐ | 109 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Absolute risk difference 2% (95% CI ‐4% to 8%); relative per cent change 2.5% (95% CI ‐4% to 9%). |

| Function WOMAC function. Scale from: 0 to 100 (lower scores indicate better function). Follow‐up: mean 12 months | The mean function in the control groups was 77 | The mean function in the intervention groups was 0 higher (5.63 lower to 5.63 higher) | ‐ | 109 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Absolute risk difference 0% (95% CI ‐6% to 6%); relative per cent change 0% (95% CI ‐7% to 7%). |

| Health‐related quality of life SF‐36 Physical Component Score. Scale from: 0 to 100 (higher scores indicate better quality of life). Follow‐up: mean 12 months | The mean health‐related quality of life in the control groups was 41 | The mean health‐related quality of life in the intervention groups was 3 lower (6.38 lower to 0.38 higher) | ‐ | 109 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Absolute risk difference ‐3% (95% CI ‐6% to 1%); relative per cent change ‐7% (95% CI ‐16% to 1%). |

| Global assessment of treatment success | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No trial reported measuring global assessment of treatment success. |

| Postoperative anxiety | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No trial reported measuring postoperative anxiety. |

| Total number of serious adverse events (infection, thrombosis, other serious adverse events | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.29 to 1.66) | 115 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ low1,2 | Absolute risk difference ‐6% (95% CI ‐19% to 8%); relative per cent change ‐31% (95% CI ‐71% to 66%). | |

| 183 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (53 to 304) | |||||

| Re‐operation rate | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No trial reported measuring re‐operation rate. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SF‐36: 36‐item Short Form; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Participants were not blind to treatment. 2 95% CIs are wide and include the null value.

Background

Hip replacement and knee replacement are commonly performed surgical procedures. Although global data are not readily available, in the US alone, over 230,000 hip and 540,000 knee replacements were carried out in 2006, up from 124,000 and 209,000, respectively, in 1994 (DeFrances 2008). Other developed economies have witnessed similar increases. In England and Wales, for example, over 89,000 hip and over 93,000 knee procedures were carried out in 2012 (NJR 2013). This trend is likely to continue as populations age and surgical techniques become more commonplace.

Description of the condition

The main indicators for hip or knee replacement are persistent pain or limitation of function (or both) that cannot be managed by conservative treatment alone (Brady 2000). The leading cause of such pain is osteoarthritis but may also include rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, congenital abnormalities, dysplasia and osteochondritic disease. In the absence of treatments that provide a cure for conditions such as osteoarthritis, management is directed primarily towards relieving pain and reducing functional limitation. Joint replacement is one surgical option when medical treatment provides inadequate symptom relief (Creamer 1998).

Description of the intervention

Preoperative education refers to any educational intervention delivered before surgery that aims to improve patients' knowledge, perspectives, health behaviours and health outcomes (Hathaway 1986; Oshodi 2007a; Oshodi 2007b; Shuldham 1999). The content of preoperative education varies across settings, but often comprises discussion of presurgical procedures, the surgical procedure, postoperative care, potential stressful scenarios associated with surgery, potential complications, pain management and movements to avoid post‐surgery (Louw 2013). Education is often provided by physiotherapists, nurses or members of multidisciplinary teams, including psychologists (Johansson 2005; Louw 2013). The format of education ranges from one‐to‐one verbal communication, group sessions, or video or booklet with no verbal communication (Hathaway 1986; Louw 2013; Shuldham 1999).

How the intervention might work

Hip or knee replacement is a major surgical procedure that requires inpatient physiotherapy and outpatient rehabilitation following a stay in hospital (Palmer 1999). These surgical procedures can be stressful, affecting the person both physically and psychologically (Gammon 1996b). Perception of pain and anxiety is often heightened when people feel a lack of control over their situation, and is very common around surgery (Bastian 2002). If a person is unduly anxious, physical recovery and well‐being may be affected, prolonging hospital stay and increasing the cost of care. By ensuring full understanding of the operation and postoperative routines, and promoting physical recovery and psychological well‐being through preparatory information, it is hypothesised that people will be less anxious, have a shorter hospital stay and be better able to cope with postoperative pain (biopsychosocial approach) (Louw 2013; Shuldham 1999). In addition, educating people about postoperative care routines may reduce the incidence of postoperative complications, the most serious of which is pulmonary embolism resulting from deep vein thrombosis (Brady 2000). A key component of preoperative education is to provide the person with a greater understanding of potential complications, such as dislocation in hip replacement, and recognition of complications, such as deep vein thrombosis. It is also important to emphasise the most common post‐surgical side effects (e.g. swelling after knee replacement around the knee and in the ankle).

Why it is important to do this review

Following the publication of the original version of this review (McDonald 2004), plus another systematic review published shortly afterwards (Johansson 2005), the evidence base for preoperative education has grown. The most recent systematic review of preoperative education for hip or knee replacement by Louw 2013 included trials published up to February 2011. The review authors chose not to synthesise the results in a meta‐analysis, though reported that of the 13 included trials, only one had a positive effect on postoperative pain while the remaining trials identified no significant difference between groups on this outcome. Postoperative pain was the only outcome of interest in the Louw 2013 systematic review. Therefore, an up‐to‐date systematic review of the efficacy and safety of preoperative education on other outcomes (e.g. function, health‐related quality of life, adverse events) is necessary.

Objectives

To determine whether preoperative education in people undergoing total hip replacement or total knee replacement improves postoperative outcomes with respect to pain, function, health‐related quality of life, anxiety, length of hospital stay and the incidence of adverse events (e.g. deep vein thrombosis).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCT) or quasi‐randomised trials comparing educational interventions given preoperatively to people undergoing total hip or total knee replacement surgery.

Types of participants

People undergoing planned total hip or total knee replacement. We originally planned to include only trials of people undergoing surgery for osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (or where such people accounted for at least 90% of the entire trial population) to avoid clinical heterogeneity. However, few trials reported these data so we included all trials of people undergoing planned hip or knee replacement surgery.

Types of interventions

Any preoperative education regarding the surgery and its postoperative course delivered by a health professional within six weeks of surgery. Education could be given verbally or in any written or audiovisual form, and could include preoperative instruction of postoperative exercise routines.

All comparators were considered, although we excluded trials comparing various methods of delivery of preoperative education in the absence of a control group receiving standard or routine care. We also excluded trials that incorporated some form of postoperative intervention (e.g. use of reminder systems to perform exercises).

Types of outcome measures

Major outcomes

The major outcomes were:

pain measured by visual analogue scales (VAS), numerical or categorical rating scales; and

function. Where trialists reported outcome data for more than one function scale, we extracted data on the scale that was highest on the following list: 1. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) function; 2. Harris Hip Score; 3. Oxford Hip/Knee Score; 4. 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) Physical Component Score; 5. Health Assessment Questionnaire; 6. any other function scale;

health‐related quality of life measured using the SF‐36 or Nottingham Health Profile;

global assessment of treatment success as defined by the trialists (e.g. proportion of participants with significant overall improvement);

postoperative anxiety measured using the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale;

number of participants experiencing any serious adverse events (e.g. infection, deep vein thrombosis, other serious adverse events);

re‐operation rate.

Minor outcomes

Other outcomes were:

preoperative anxiety measured using the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory or Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale;

length of hospital stay;

mobility (number of days to stand or walk);

range of motion.

Time points

For this update of the review, we did not pre‐specify a primary time point. We extracted data from all time points and performed separate analyses (forest plots not shown) to include all available studies per outcome per time point. There did not appear to be an effect of time on any outcome, so we chose to include only the latest time point available per outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases, unrestricted by date or language, up to 31 May 2013:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 5, 2013);

MEDLINE (Ovid);

EMBASE (Ovid);

CINAHL (EBSCO);

PsycINFO (Ovid).

We also searched the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) in July 2010.

We used specific subject headings and additional text words describing the intervention and participants to identify relevant trials. The complete search strategy for the MEDLINE database is provided in Appendix 1. This strategy was adapted for the other electronic databases as appropriate (Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5).

We searched for ongoing randomised trials and protocols of published trials in the clinical trials register maintained by the US National Institute of Health (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (www.who.int/ictrp/en/).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the Australian Journal of Physiotherapy (1954 to 2009) and screened the reference lists of retrieved review articles and reports of trials to identify potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

The description below relates to the methods for data collection and analysis applied during the update of this review in 2013. The previous version of this review (published in 2003) followed methods recommended at that time.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SM, KB) independently selected the trials to be included in the review. We retrieved all articles selected by at least one of the review authors for closer examination. We resolved disagreements through discussion or by consulting a third review author (JW).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SM, KB) independently extracted the following data from the included trials and entered the data in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012). The third and fourth review authors (JW, MP) checked the data.

Design, size and location of the trial.

Characteristics of the trial population including age, gender, reason for undergoing surgery and any reported exclusion criteria.

Description of the intervention including the content and format of the preoperative education, the timing and duration of its delivery, and the type of personnel involved.

Methodological characteristics as outlined below in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Outcome measures ‐ number of events for dichotomous outcomes, and means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes.

Multiplicity of outcome data is common in RCTs (Page 2013). We used the following a priori decision rules to select which data to extract:

where trialists reported both final values and change from baseline values for the same outcome, we extracted final values;

where trialists reported both unadjusted and adjusted values for the same outcome, we extracted unadjusted values; and

where trialists reported data analysed based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) sample and another sample (e.g. per‐protocol, as‐treated), we extracted ITT‐analysed data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The same two review authors (SM, KB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included trial and resolved any disagreement through discussion or consultation with the third and fourth review authors (JW, MP). We assessed the following methodological domains, as recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011):

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other potential threats to validity.

Each of these criteria were explicitly judged as: low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias (either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). As part of the updating process, we completed the risk of bias assessment for the nine original included trials.

Measures of treatment effect

As far as possible, the analyses were based on ITT data (outcome data provided for every randomised participant) from the individual trials. For each trial, we present continuous outcome data as point estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We presented the results for continuous outcomes as mean differences (MD) if outcomes included in a meta‐analysis were measured using the same scale. If outcomes were measured using different scales, we pooled data using standardised mean differences (SMD). We presented the results of dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RR).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant. None of the trials were cluster trials and we did not identify any trials in which participants underwent double knee or double hip replacements.

Dealing with missing data

We requested additional trial details and data from trial authors when the data reported were incomplete.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by determining whether participants, interventions, comparators, outcome measures and timing of outcome assessment were similar across the included trials. We quantified statistical heterogeneity across trials using the I2 statistic. We interpreted the I2 statistic using the following as an approximate guide: 0% to 40% might not be important heterogeneity; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess publication bias, we would have generated funnel plots if at least 10 trials examining the same treatment comparison were included in a meta‐analysis (Sterne 2011); however, we identified too few trials to undertake this analysis. To assess outcome reporting bias, we planned to compare the outcomes specified in trial protocols with the outcomes reported in the corresponding trial publications. If trial protocols were unavailable, we compared the outcomes reported in the methods and results sections of the trial publications (Dwan 2011). We generated an Outcome Reporting Bias In Trials (ORBIT) Matrix (ctrc.liv.ac.uk/orbit/) using the ORBIT classification system (Kirkham 2010).

Data synthesis

We anticipated substantial clinical heterogeneity between trials, so we used a random‐effects model for all meta‐analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

We collated the main results of the review into 'Summary of findings' tables, which provide key information concerning the quality of evidence and the magnitude and precision of the effect of the interventions (Schünemann 2011a). We included the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables: pain, function, health‐related quality of life, global assessment of treatment success, postoperative anxiety, total adverse events (infection, thrombosis, other serious adverse events) and re‐operation rate. For all outcomes, data for the latest time point available were included. Outcomes pooled using SMDs were re‐expressed as MDs by multiplying the SMD by a representative control group baseline standard deviation from a trial, using a familiar instrument. The 'Summary of findings' table includes an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes, using the GRADE approach (considers study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence for each outcome (Schünemann 2011b).

In addition to the absolute and relative magnitude of effect provided in the 'Summary of findings' table, we have reported the absolute per cent difference, the relative per cent change from baseline, and the number needed‐to‐treat (NNT) for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (the NNT was only provided for outcomes that shows a statistically significant difference).

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the absolute risk difference using the risk difference statistic in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012) and the result expressed as a percentage; the relative percentage change was calculated as the RR ‐ 1 and was expressed as a percentage; and the NNT from the control group event rate and the RR were determined using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2008).

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the absolute risk difference as the MD between intervention and control groups in the original measurement units (divided by the scale), expressed as a percentage; the relative difference was calculated as the absolute change (or MD) divided by the baseline mean of the control group from a representative trial. We used the Wells calculator to obtain the NNTB for continuous measures (available at the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group (CMSG) Editorial office; musculoskeletal.cochrane.org/). The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for each outcome was determined for input into the calculator. We assumed an MCID of 1.5 points on a 10‐point pain scale (15 points on 100‐point scale), and 10 points on a 100‐point scale for function or disability (Gummesson 2003) for input into the calculator.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan or undertake any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate the robustness of the treatment effect for postoperative pain and postoperative function to allocation concealment by removing the trials that reported inadequate or unclear allocation concealment from the meta‐analysis to see if this changed the overall treatment effect.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

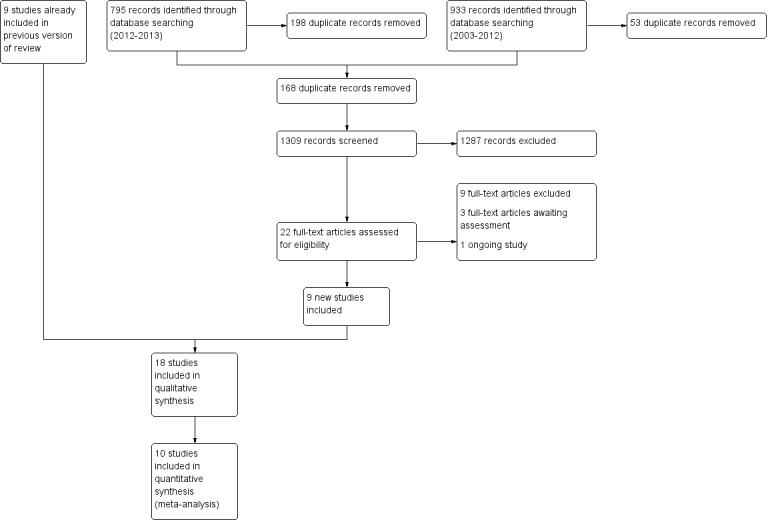

The database searches were revised and re‐run in both June 2012 and May 2013 to cover the period from 2003 to 2013. Following the process of automatic deduplication, the updated search identified 1309 records. From screening the titles and abstracts of the 1309 records, we excluded 1287 records that were clearly not relevant. Of the 22 potentially eligible full‐text reports assessed, we identified nine trials that met our inclusion criteria (see flow chart in Figure 1). Nine excluded trials are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Three trials are awaiting assessment (Eschalier 2012; Huang 2012; Wilson 2012), and one trial is ongoing (Riddle 2012). The nine new included trials (Beaupre 2004; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Johansson 2007; McDonald 2004; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Sjöling 2003; Vukomanović 2008) were added to the existing nine trials from the previous version (Butler 1996; Clode‐Baker 1997; Cooil 1997; Crowe 2003; Daltroy 1998; Doering 2000; Lilja 1998; Santavirta 1994; Wijgman 1994). The earliest trials were published in 1994 and the most recent in 2008. All trials were published in English with the exception of Wijgman 1994, which was published in Dutch.

1.

Trial flow diagram for the review update (literature searches from 2003 to 2013).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

Seventeen of the included trials were randomised and one was quasi‐randomised (Sjöling 2003). Sixteen were two‐arm trials, one was a three‐arm trial (McDonald 2004), and one was a four‐arm trial (Daltroy 1998). One trial used stratification to produce balanced groups according to age (Daltroy 1998), and another used gender, age and socioeconomic status (Cooil 1997).

Setting

Trials were set in hospitals and were conducted in North America or Europe; five each in Scandinavia and continental Europe, three each in Canada and the UK, and two in the USA. With the exception of Siggeirsdottir 2005, trials were conducted at a single site.

Participants

Thirteen trials involved people undergoing hip replacement (Butler 1996; Clode‐Baker 1997; Cooil 1997; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Johansson 2007; Lilja 1998; McGregor 2004; Santavirta 1994; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994); three involved people undergoing knee replacement (Beaupre 2004; McDonald 2004; Sjöling 2003); and two included people with both hip and knee replacements (Crowe 2003; Daltroy 1998). Overall, the 18 included trials involved 1463 participants (range 26 to 222). The number of people undergoing hip replacement was 1074 (73% of the total). Most participants were women (59%) and the mean age of participants was within the range of 58 to 73 years, with the exception of Gocen 2004.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria varied considerably between the trials. Half of the trials reported age as an inclusion criterion, with none of these explicitly excluding older people. The most commonly stated exclusion criteria were previous hip or knee replacement surgery and difficulties in communicating (reading, writing and language). The patient profile differed most markedly in Crowe 2003 since the inclusion criteria deliberately targeted people with poor functioning, limited social support and existing co‐morbidities.

Interventions

The nature, content and timing of the preoperative education varied considerably between trials. In four trials, participants received written information in addition to one or more education sessions before admission to hospital (Giraudet 2003; Johansson 2007; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005). Written information alone was provided before admission in one trial (Butler 1996). Santavirta 1994 combined the provision of pre‐admission written information with a teaching session on admission that was planned according to the needs of each participant. Sjöling 2003 also provided a teaching session on admission, though in this trial the written information was distributed at the time of the education session rather than before.

Five trials included an audiovisual component. Clode‐Baker 1997 sent written information, a video and plastic model bones to participants before admission; Crowe 2003 combined a video presentation with an individually tailored programme of education before admission; McDonald 2004 showed either one of two films to participants in two of the intervention groups after the standard preoperative class; Daltroy 1998 and Doering 2000 showed participants a video after admission in the presence of the investigator. In six trials, information was provided in teaching sessions delivered by physiotherapists or nurses; three of these took place before admission (Beaupre 2004; Gocen 2004; Vukomanović 2008), and three after admission (Cooil 1997; Lilja 1998; Wijgman 1994).

All trials provided some form of standardised information for participants, consisting mainly of printed materials, thus ensuring all participants (including people in the control group) received some information before surgery. Detailed descriptions of the content and methods used to deliver the education interventions are given in Table 3.

1. Description of the education intervention.

| Trial ID | Content |

| Beaupre 2004 | Participants in the treatment group underwent a 4‐week exercise/education programme before surgery. The education programme consisted of instruction regarding crutch walking, bed mobility and the postoperative range of motion routine. The exercise programme was designed to improve knee mobility and strength using simple exercises with progressive resistance. The subjects were asked to attend the treatment programme three times a week for four weeks. |

| Butler 1996 | An 18‐page teaching booklet 'Total hip replacement: a patient guide' was sent to participants at home. The booklet was developed by a multidisciplinary team and contained: information on the anatomy of a normal and diseased hip; total hip prosthesis; exercises to practice before admission; what to expect in hospital; precautions following surgery and planning for discharge. The booklet had a readability age of Grade 6 to 7 with 22 drawings and photographs. |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | A 20‐minute video, booklet and set of plastic models were sent to participants at home. The video followed the progress of a person undergoing hip replacement surgery, from difficulties encountered at home through to the hospital stay, postoperative recovery and exercises. The booklet addressed similar issues and included advice from previous participants. The booklet described arthritis and backed up information presented in the video. The life‐size plastic model bones demonstrated changes of the total hip replacement by comparison with a normal hip joint, osteoarthritis and an implanted total hip replacement prosthesis. |

| Cooil 1997 | An information sheet that was already in clinical use was made available at the participants' bedside. The sheet contained instructions on the postoperative protocol, exercises and advice on beneficial and harmful postoperative activities. In addition, a verbal explanation of the sheet's contents was given, and the exercises and activities were taught through demonstration and practiced under supervision. |

| Crowe 2003 | A preoperative education package consisting of a 50‐minute video and a booklet giving information on length of hospital stay, discharge criteria, respite care and diet was provided to participants the first time they visited the clinic following randomisation. The video focused on the participant's responsibility during the postoperative phase and use of equipment. Some participants were given a tour of the hospital unit, demonstration of equipment, dietician counselling and social work input. All participants received extensive individualised counselling from an occupational therapist on all aspects of optimising function and independence postoperatively, including home assessments, and were provided with a telephone contact for additional information. A physical conditioning programme was available to participants to improve strength and endurance and facilitate postoperative mobility. Participants also received the same standard preoperative clinic visit as the control participants. |

| Daltroy 1998 | A 12‐minute audiotape slide programme was presented by a research assistant at the bedside the day before surgery. The audiotape oriented the participant to the hospital, staff, surgery and rehabilitation. Participants were told of various stressful aspects of their hospital stay, and reassured that these were normal. The tape complemented the standard preoperative information. The comparison group received relaxation training consisting of oral and written instructions and an 18‐minute audiotape. |

| Doering 2000 | A 12‐minute video shown in hospital preoperatively in the presence of the investigator. The video followed a person with osteoarthritis undergoing hip replacement. Filmed from the person's perspective, the video showed what to expect from hospital, the procedure, the recovery and rehabilitation. It included original dialogue, a narrator giving procedural information and interviews with the person. |

| Giraudet 2003 | Participants in the multidisciplinary collective information group (trial group) received verbal information and a standard information leaflet. They also attended an education session 2 to 6 weeks before surgery, where a multidisciplinary team including a surgeon and an anaesthetist presented a standardised education programme. The team discussed the intervention and answered the questions of patients and their significant others. The control group received only the usual verbal information from the surgeon and the anaesthetist and the standard information leaflet. |

| Gocen 2004 | Participants in the trial group received preoperative physiotherapy to strengthen and improve range of motion of the hip, beginning from eight weeks before the operation. These participants also received an educational programme that included advice on movements that should be avoided, use of assistance devices, posture, lifting and carrying, washing and bathing. The control group received no preoperative physiotherapy or educational programme. |

| Johansson 2007 | Standard written education materials plus education using the concept map method. The education was delivered by two specially trained nurses two weeks before admission and lasted approximately 30 to 60 minutes. The concept map method involved counselling in relation to biophysiological, functional, experiential, ethical, social and financial issues about pre and postoperative care. |

| Lilja 1998 | In addition to being informed by ward nurses about preoperative routines and what to expect before and after the operation, participants spent 30 minutes with an anaesthetic nurse. The information provided by the nurse covered the importance of preoperative preparation and patient participation in recovery, the operating theatre and mobilisation following surgery. |

| McDonald 2004 | Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups. In the preoperative period, the communication group (treatment group) viewed a 4‐minute pain communication film as well as a 10‐minute pain management film. Comparison group 1 viewed only the pain management film, and comparison group 2 received standard care only. Handouts reinforcing the main content of both films were distributed to the communication group. Comparison group 1 received only the pain management handout. |

| McGregor 2004 | Participants in the treatment group received a preoperative hip class 2 to 4 weeks before surgery and an information booklet. The information booklet documented information on the surgery, rehabilitation stages including exercise regimens, and answers to commonly asked questions. The preoperative class enforced the booklet and ensured that all participants could do the exercises, understood how to use walking aids postoperatively, and could adapt their homes for the recovery period. The control group received the standard preoperative treatment, which included a description of the surgery and its risks and approximations on length of hospital stay. |

| Santavirta 1994 | Before admission, participants received an 18‐page guide on hip replacement surgery and postoperative rehabilitation. They also received a 20‐ to 60‐minute teaching session by the investigator, which was planned according to each participant's situation. Elements covered included safe walking, active exercises, wound care, temperature taking, rehabilitation and discharge planning. |

| Siggeirsdottir 2005 | Participants in the trial group participated in a preoperative education and training programme, given by a physiotherapist or an occupational therapist (or both), about one month before the planned operation. The programme covered postoperative rehabilitation, exercises and postoperative assistive devices. Participants also received an illustrated brochure containing information on how to move and exercise postoperatively. When a trial group participant was discharged, a physiotherapist or occupational therapist could accompany the person home and return for follow‐up home visits if this was considered necessary. Control group participants were treated according to the clinical procedures already in use and were discharged when rehabilitated, or could be transferred to another rehabilitation facility. |

| Sjöling 2003 | Participants received specific information (verbally and in a leaflet) which emphasised the person's own role in pain management by trying to improve knowledge in areas important for their well‐being. The specific information covered issues such as people taking an active role in their treatment; postoperative pain and pain management; and the importance of physiotherapy. |

| Vukomanović 2008 | Participants received short‐term intensive preoperative preparation consisting of education and elements of physiotherapy. They were informed about the operation, caution measures and rehabilitation following the operation through conversation with the clinician and a brochure. They were instructed by a physiotherapist to perform exercises and basic activities. |

| Wijgman 1994 | Participants received preoperative instructions for 30 minutes in groups of 4 to 6 delivered by two physiotherapists. They also received preoperative exercise therapy including muscle setting exercises. |

The nature of the intervention and the patient profile differed most markedly in Crowe 2003. In this trial, various interventions tailored to individual needs were offered to participants in addition to educational material. In contrast to all other trials, the inclusion criteria deliberately targeted people with poor functioning, limited social support and existing co‐morbidities. Only one other trial incorporated tailoring the intervention (a teaching session) to each participant's specific situation (Santavirta 1994).

Outcomes

The outcomes measured varied considerably (see Table 4), though many trials only partially reported results (e.g. reported the difference between groups as being non‐significant, though did not report the summary statistics required for meta‐analysis). Of the primary outcomes, 11 trials reported measuring pain, but only five trials reported data in a format suitable for analysis (Beaupre 2004; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; McDonald 2004; McGregor 2004), whereas five trials measured and fully reported data for function (Beaupre 2004; Gocen 2004; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008), and five trials measured adverse events, of which three fully reported outcome data (Beaupre 2004; Giraudet 2003; Siggeirsdottir 2005). The most common fully reported outcomes were length of hospital stay (eight trials: Beaupre 2004; Butler 1996; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994), and mobility (days to stand or walk) (six trials: Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994).

2. Outcome Reporting Bias In Trials (ORBIT) outcome matrix.

| Study ID | Major outcomes | Minor outcomes | Other outcomes | |||||||||

| Pain | Function | HRQoL | Global assessment | Postop anxiety | Adverse events | Re‐operation rate | Preop anxiety | LOS | Mobility | ROM | Knowledge (recall) | |

| Beaupre 2004 | Full | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Full | Unclear |

| Butler 1996 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Partial | Unclear | Unclear |

| Cooil 1997 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial |

| Crowe 2003 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear |

| Daltroy 1998 | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Doering 2000 | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear |

| Giraudet 2003 | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Unclear | Full | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear |

| Gocen 2004 | Partial | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Full | Full | Unclear |

| Johansson 2007 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Partial |

| Lilja 1998 | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| McDonald 2004 | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| McGregor 2004 | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Santavirta 1994 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial |

| Siggeirsdottir 2005 | Unclear | Full | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Sjöling 2003 | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Vukomanović 2008 | Partial | Full | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Full | Unclear |

| Wijgman 1994 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Full | Full | Unclear | Unclear |

HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; LOS: length of hospital stay; preop: preoperative; postop: postoperative; ROM: range of motion.

'Full' = sufficient data for inclusion in a meta‐analysis were reported (e.g. mean, standard deviation, and sample size per group for continuous outcomes).

'Partial' = insufficient data for inclusion in a meta‐analysis were reported (e.g. means only, with no measures of variation).

'Unclear' = unclear whether the outcome was measured or not (as a trial protocol was unavailable).

Excluded studies

We excluded trials for the following reasons: information was not specific to hip or knee surgery (Bondy 1999; Mikulaninec 1987); trial was not randomised (Hough 1991; Roach 1995); participants received a combined pre‐ and postoperative intervention (Gammon 1996a; Pour 2007; Ródenas‐Martínez 2008; Wong 1985); trial investigated the effect of preoperative depression on postoperative recovery and was not a randomised trial of preoperative education (Brull 2002); and the trial did not investigate postoperative outcomes (Haslam 2001) (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

Risk of bias in included studies

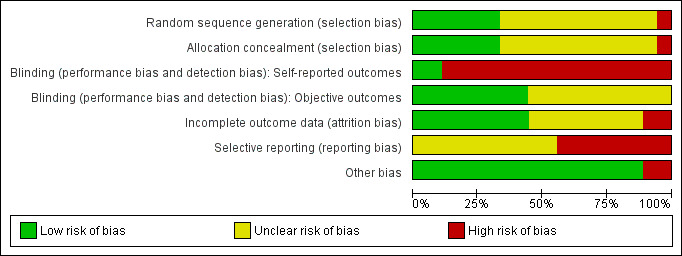

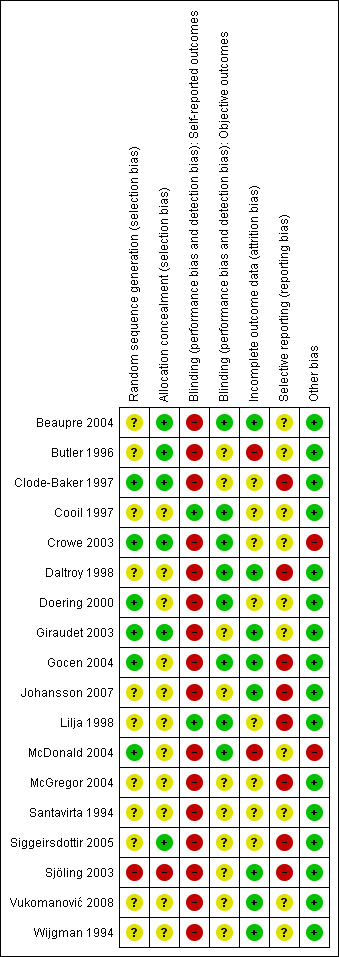

See Characteristics of included studies table. The results of the risk of bias assessment are also presented graphically in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

3.

Allocation

We assessed three trials as low risk of selection bias having both adequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment (Clode‐Baker 1997; Crowe 2003; Giraudet 2003). We assessed three other trials as low risk of selection bias on the basis of adequate allocation concealment even though the method of random sequence generation was not specified (Beaupre 2004; Butler 1996; Siggeirsdottir 2005). We assessed risk of selection bias as unclear in eight trials reported to be randomised since neither the methods of random sequence generation nor treatment allocation were specified (Cooil 1997; Daltroy 1998; Johansson 2007; Lilja 1998; McGregor 2004; Santavirta 1994; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994). We assessed a further three trials as unclear risk of selection bias despite reporting an adequate method for the random sequence generation because the method of treatment allocation was either not specified (Doering 2000; McDonald 2004), or unclear (Gocen 2004). We assessed one trial as high risk of selection bias as participants were allocated to groups on an alternate basis (Sjöling 2003).

Blinding

Blinding was considered by type of outcome (self reported and objective). For self reported outcomes, two trials attempted to blind participants by not informing them of the aim and design of the trial (Lilja 1998), and by obscuring the purpose of the trial during the explanation to participants (Cooil 1997). We rated the remaining 16 trials at high risk of bias because blinding of participants was either not attempted or not described (but since blinding is difficult to achieve with an educational intervention, it was likely not to have been attempted).

Blinding of outcome assessors for the objective outcomes was attempted in eight trials (Beaupre 2004; Cooil 1997; Crowe 2003; Daltroy 1998; Doering 2000; Gocen 2004; Lilja 1998; McDonald 2004), though measures of success of blinding were not provided. It is feasible that participants may have accidentally unblinded assessors by describing a facet of their preoperative care. The remaining 10 trials did not provide any details about the blinding of objective outcomes so we rated them as having unclear risk of bias on this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data were not particularly well accounted for. We assessed eight trials as low risk of bias (Beaupre 2004; Daltroy 1998; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Johansson 2007; Sjöling 2003; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994). Of these, Beaupre 2004 explained the distribution of, and reasons for, incomplete data and used statistical strategies to compensate for missing values. The remaining seven trials described drop‐outs adequately without correcting statistically for missing values. However, we considered the drop‐outs were unlikely to have affected the results because the missing values were small and the outcomes were continuous. We rated eight trials as unclear in their reporting of incomplete data either because the amount or reasons for missing data were not explained (Clode‐Baker 1997; Cooil 1997; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Lilja 1998; McGregor 2004; Santavirta 1994; Siggeirsdottir 2005). We assessed two trials as high risk of bias: Butler 1996 had unexplained missing values in all data (ranging from 2 to 12 participants missing); and McDonald 2004 removed some data post‐hoc due to author interpretation.

Selective reporting

We rated eight trials at high risk of selective reporting bias because the data necessary to include the trial in a meta‐analysis of at least one outcome (e.g. standard deviations) were not reported (Clode‐Baker 1997; Daltroy 1998; Gocen 2004; Johansson 2007; Lilja 1998; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Sjöling 2003). We rated all remaining trials as unclear risk of bias because trial protocols were unavailable, making it impossible to determine whether additional outcomes were measured but not reported based on the results.

Other potential sources of bias

We rated two trials at high risk of other bias. The control group in Crowe 2003 had worse function at baseline, and this baseline imbalance may have biased the results to favour the intervention group. McDonald 2004 reported changing the protocol in order to minimise confounding, but this was done after the initial data analysis (i.e. result‐driven modification).

Effects of interventions

Eleven trials presented data in a format suitable for analysis (i.e. number of participants with events or means and standard deviations) (Beaupre 2004; Butler 1996; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; McDonald 2004; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994). The data from three other trials were reported as medians and ranges and are reported in an additional table (Clode‐Baker 1997; Johansson 2007; Sjöling 2003) (Table 5). The remaining four trials either did not measure any outcomes of interest to the review or partially reported outcome data (Cooil 1997; Daltroy 1998; Lilja 1998; Santavirta 1994). Despite attempts to contact all authors, we were only able to secure additional data for three trials (Butler 1996; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000). Although the trials differed somewhat in the participant characteristics and intervention components, we judged that there was sufficient clinical homogeneity to pool the results using random‐effects meta‐analyses.

3. Results of included studies with data not appropriate for meta‐analysis.

| Trial ID | Outcome | Results |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Preoperative anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 0 to 21) | Intervention: median 6 (range 1 to 17). Control: median 8 (range 2 to 21). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Postoperative anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 0 to 21) | Intervention: median 5 (range 1 to 15). Control: median 5 (range 1 to 15). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Nottingham Health Profile (postoperative) (0 to 38) | Intervention: median 10 (range 1 to 29). Control: median 9 (range 0 to 19). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Days to mobilisation | Intervention: median 2 (range 1 to 6). Control: median 2 (range 2 to 3). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Clode‐Baker 1997 | Length of hospital stay | Intervention: median 12 (range 7 to 21). Control: median 12 (range 7 to 23). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Johansson 2007 | Length of hospital stay | Intervention: mean 6.78. Control: mean 8.18. Not statistically significant. |

| Sjöling 2003 | VAS pain postoperative day 1 | Intervention: median 4 (IQR 3.3 to 5.7; range 2 to 9.3). Control: median 4.3 (IQR 2.2 to 6; range 0 to 8.3). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Sjöling 2003 | VAS pain postoperative day 2 | Intervention: median 3.8 (IQR 2.6 to 5.1; range 1 to 9.3). Control: median 4.0 (IQR 3.3 to 5; range 0 to 7.3). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Sjöling 2003 | VAS pain postoperative day 3 | Intervention: median 3.0 (IQR 1.7 to 3.7; range 0 to 7.7). Control: median 2.3 (IQR 1.7 to 4.2; range 0 to 8.3). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

| Vukomanović 2008 | VAS pain at discharge | Intervention: mean 3.95, SD 13.08, median 0 (range 0 to 58). Control: mean 6.2, SD 14.95, median 0 (range 0 to 50). No statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. |

IQR: interquartile range; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care

See Table 1.

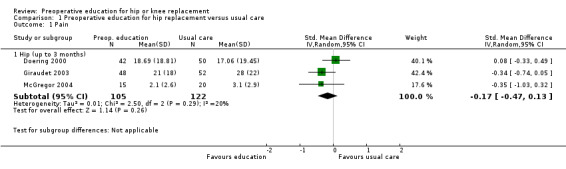

Pain

See Analysis 1.1. Three trials measured useable outcome data for postoperative pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS) at at least one time point (Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; McGregor 2004). At up to three months postoperatively, pain was lower in participants receiving preoperative education, though the difference was not statistically significant (3 trials, 227 participants, SMD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.47 to 0.13; I2 = 20%; this is equivalent to a MD of ‐0.34 points (95% CI ‐0.94 to 0.26) on a 10‐point scale). Clode‐Baker 1997 measured pain using a 6‐point ordinal scale and only reported that there was no statistically significant difference between groups on this outcome at the end of the first postoperative week. Daltroy 1998 only reported that pain measured on a 1 to 5 scale was not statistically significantly different between groups four days postoperatively. Gocen 2004 reported measuring pain but reported no results in the publication. Lilja 1998 only reported mean scores for VAS pain and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on day one, two and three postoperatively. Sjöling 2003 reported median (interquartile range (IQR)) data for VAS pain and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on postoperative day one, two and three (see Table 5). Vukomanović 2008 reported skewed data for VAS pain and identified no statistically significant difference between groups at hospital discharge (see Table 5).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 1 Pain.

Function

See Analysis 1.2. Four trials measured postoperative function using either the WOMAC function, Oxford Hip Score, or Harris Hip Score (Gocen 2004; McGregor 2004; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008). Participants receiving preoperative education had better function scores compared with people receiving usual care at 3 to 24 months postoperatively (4 trials, 177 participants, SMD ‐0.44; 95% CI ‐0.93 to 0.06; I2 = 61%; this is equivalent to a MD of ‐4.84 points (95% CI ‐10.23 to 0.66) on the WOMAC Likert (0 to 68) scale). However, participants were not blind to treatment in any of these trials, so self reported function may have been overestimated by participants receiving preoperative education. No other hip replacement trials reported measuring function.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 2 Function.

Health‐related quality of life

Two trials reported measuring health‐related quality of life (Clode‐Baker 1997; Siggeirsdottir 2005), but neither presented outcome data in a format suitable for inclusion in a meta‐analysis. Clode‐Baker 1997 reported median (IQR) data for the Nottingham Health Profile and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on this outcome (see Table 5). Siggeirsdottir 2005 also used the Nottingham Health Profile and reported that the usual care group had lower scores on this outcome, but did not report the statistical significance of the difference.

Global assessment of treatment success

Global assessment of treatment success was not assessed in any of the trials included in the review.

Postoperative anxiety

See Analysis 1.3. Three trials measured postoperative anxiety using the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Index at different time periods (Butler 1996; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003). Anxiety was 2.28 points lower (on the 60‐point scale) at up to six weeks postoperatively in participants receiving preoperative education, though this difference was not statistically significant (3 trials, 264 participants, MD ‐2.28; 95% CI ‐5.68 to 1.12; I2 = 22%). Clode‐Baker 1997 reported median (IQR) data for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale postoperatively and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on this outcome (see Table 5). Daltroy 1998 only reported that anxiety measured on a 1 to 4 scale was not statistically significantly different between groups four days postoperatively. Lilja 1998 only reported mean scores for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on day one, two and three postoperatively.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 3 Postoperative anxiety (Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Index).

Adverse events

See Analysis 1.4. Four trials reported measuring adverse events (Giraudet 2003; McGregor 2004; Santavirta 1994; Siggeirsdottir 2005), but only two reported sufficient data to include in a meta‐analysis (Giraudet 2003; Siggeirsdottir 2005). The risk of experiencing any serious postoperative complication was reduced by 21% in participants receiving preoperative education, though this effect was not statistically significant (2 trials, 31 participants, RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.19 to 3.21; I2 = 78%). McGregor 2004 reported that some participants reported minor postoperative complications and that these were similar in number between groups, and Santavirta 1994 reported that there was no statistical difference in the number of early complications. No trial referred specifically to incidence of infection or deep vein thrombosis.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 4 Total number of serious adverse events.

Re‐operation rate

Re‐operation rate was not assessed in any of the trials included in the review.

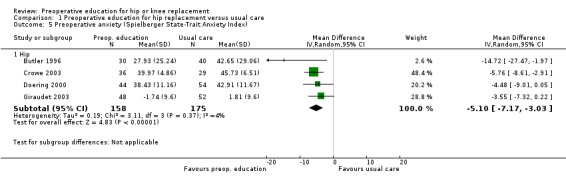

Preoperative anxiety

See Analysis 1.5. Four trials measured preoperative anxiety using the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Index (range of scores 20 to 80) (Butler 1996; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003). Preoperative education resulted in preoperative anxiety that was 5.1 points lower (on the 60‐point scale) compared with usual care (4 trials, 333 participants, MD ‐5.10; 95% CI ‐7.17 to ‐3.03; I2 = 4%). However, participants were not blind to treatment in any of these trials, so self reported anxiety may have been overestimated by participants receiving preoperative education. Clode‐Baker 1997 reported median (IQR) data for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale preoperatively and identified no statistically significant difference between groups on this outcome (see Table 5). Lilja 1998 only reported mean scores for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and identified no statistically significant difference between groups preoperatively. Sjöling 2003 only reported that there was no statistically significant difference between groups in state or trait anxiety preoperatively.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 5 Preoperative anxiety (Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Index).

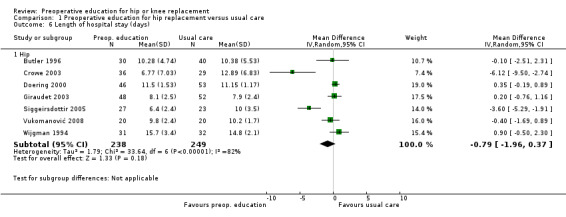

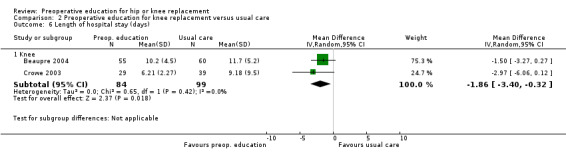

Length of hospital stay

See Analysis 1.6. Seven trials measured length of hospital stay (days) (Butler 1996; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Siggeirsdottir 2005; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994). Preoperative education resulted in a non‐statistically significant reduction in length of hospital stay by less than one day (7 trials, 487 participants, MD ‐0.79; 95% CI ‐1.96 to 0.37; I2 = 82%). Note that the high statistical heterogeneity suggests that this result should be interpreted with caution. Clode‐Baker 1997 reported median (IQR) data and Johansson 2007 reported mean values only, and both identified no statistically significant difference between groups on this outcome (see Table 5). Daltroy 1998; Gocen 2004; and Sjöling 2003 only reported that there were no statistically significant differences between groups in length of hospital stay.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 6 Length of hospital stay (days).

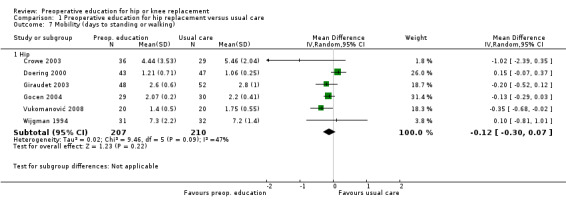

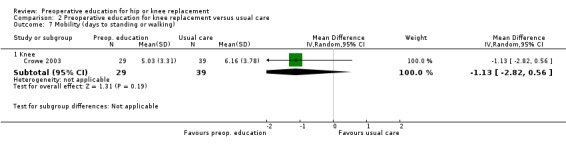

Mobility

See Analysis 1.7. Six trials reported data on mobility (Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Vukomanović 2008; Wijgman 1994). Preoperative education did not result in a statistically significant reduction in days to stand or walk (6 trials, 417 participants, MD ‐0.12; 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.07; I2 = 47%). Clode‐Baker 1997 reported median (IQR) data and identified no difference between groups on this outcome (see Table 5).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 7 Mobility (days to standing or walking).

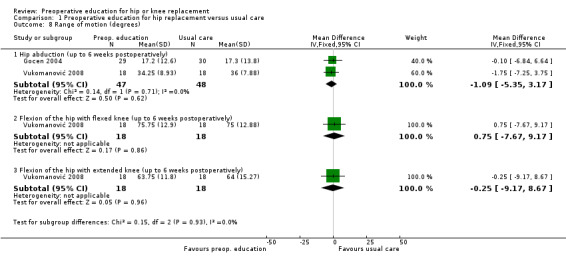

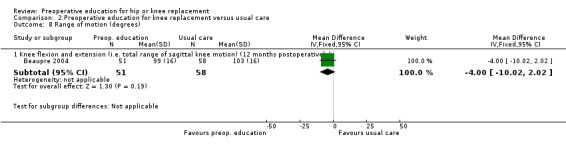

Range of motion

See Analysis 1.8. Two trials assessed various measures of hip range of motion (degrees) at up to six weeks postoperatively (Gocen 2004; Vukomanović 2008). None of the differences between groups on any measure of range of motion were clinically or statistically significant (hip abduction: 2 trials, 95 participants, MD ‐1.09; 95% CI ‐5.35 to 3.17; I2 = 0%; flexion of the hip with flexed knee: 1 trial, 36 participants, MD 0.75; 95% CI ‐7.67 to 9.17; flexion of the hip with extended knee: 1 trial, 36 participants, MD ‐0.25; 95% CI ‐9.17 to 8.67).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 8 Range of motion (degrees).

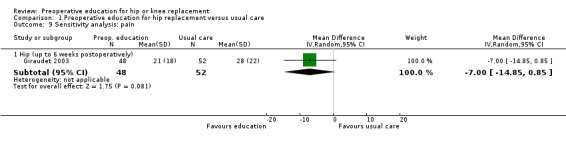

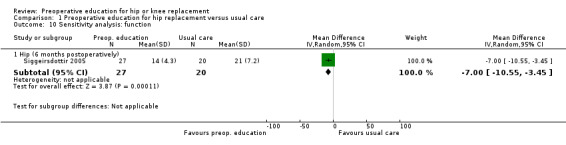

Sensitivity analyses

See Analysis 1.9 and Analysis 1.10. For the outcome of pain, after removing trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment, only one of the trials remained (Giraudet 2003). Similar to the main analysis, there were no statistically significant differences in pain at up to six weeks postoperatively (1 trial, 100 participants, MD ‐7.00; 95% CI ‐14.85 to 0.85). For the outcome of function, one of four trials with adequate allocation concealment remained (Siggeirsdottir 2005). This trial found that function was 7 points lower on the Oxford Hip Scale (0‐60 scale) in the group receiving preoperative education at six months postoperatively (1 trial, 47 participants, MD ‐7.00; 95% CI ‐10.55 to ‐3.45); however, non‐blinded participants receiving preoperative education may have overestimated their self reported function.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 9 Sensitivity analysis: pain.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative education for hip replacement versus usual care, Outcome 10 Sensitivity analysis: function.

Preoperative education for knee replacement versus usual care

See Table 2.

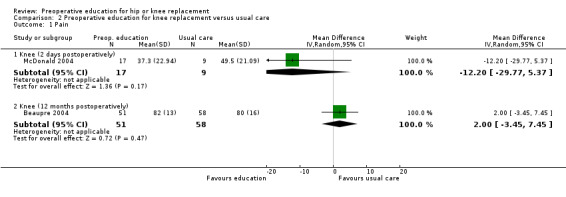

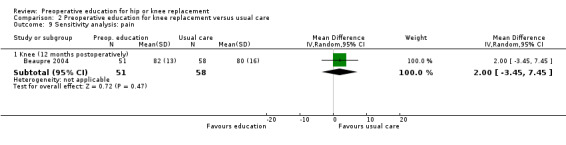

Pain

See Analysis 2.1. Two trials measured postoperative pain using a VAS at at least one time point (Beaupre 2004; McDonald 2004). Differences between groups on a 100‐point scale were small and not statistically significant at two days postoperatively (1 trial, 26 participants, MD ‐12.20; 95% CI ‐29.77 to 5.37) or 12 months postoperatively (1 trial, 109 participants, MD 2.00; 95% CI ‐3.45 to 7.45). We chose not to combine these RCTs in a meta‐analysis given the considerable heterogeneity in time points.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Preoperative education for knee replacement versus usual care, Outcome 1 Pain.

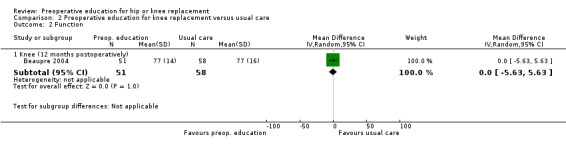

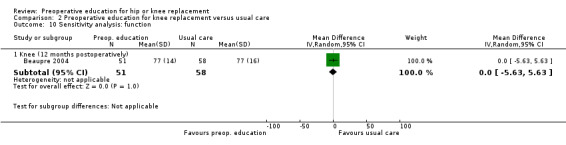

Function

See Analysis 2.2. One trial measured postoperative function using the WOMAC function (Beaupre 2004). Participants receiving preoperative education had function scores that were not statistically significantly different from people receiving usual care at 12 months postoperatively on a 100‐point scale (1 trial, 109 participants, MD 0; 95% CI ‐5.63 to 5.63).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Preoperative education for knee replacement versus usual care, Outcome 2 Function.

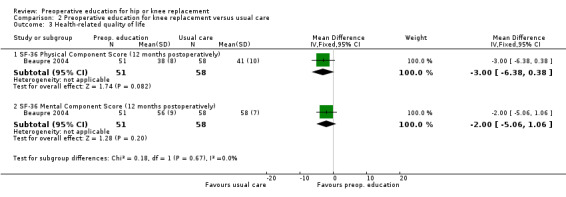

Health‐related quality of life

See Analysis 2.3. One trial measured health‐related quality of life using the SF‐36 (Beaupre 2004). At 12 months postoperatively, scores were lower (worse) for the preoperative education group on the Physical Component Score (1 trial, 109 participants, MD ‐3.00; 95% CI ‐6.38 to 0.38) and Mental Component Score (1 trial, 109 participants, MD ‐2.00; 95% CI ‐5.06 to 1.06), but these differences were not statistically significant.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Preoperative education for knee replacement versus usual care, Outcome 3 Health‐related quality of life.

Global assessment of treatment success

Global assessment of treatment success was not assessed in any of the trials included in the review.

Postoperative anxiety

Postoperative anxiety was not assessed in any of the trials included in the review.

Adverse events

See Analysis 2.4. One trial measured adverse events (Beaupre 2004). The risk of experiencing any serious postoperative complication was reduced by 31% in participants receiving preoperative education, though this effect was not statistically significant (1 trial, 115 participants, RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.66). Risk ratios for each type of postoperative complication were as follows: deep vein thrombosis (1 trial, 115 participants, RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.14 to 2.08); pulmonary emboli (1 trial, 115 participants, RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.16 to 7.48); and infection (1 trial, 115 participants, RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.13 to 4.19).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Preoperative education for knee replacement versus usual care, Outcome 4 Total number of serious adverse events.