Abstract

Background

All major guidelines for antihypertensive therapy recommend weight loss. Thus dietary interventions that aim to reduce body weight might be a useful intervention to reduce blood pressure and adverse cardiovascular events associated with hypertension.

Objectives

Primary objectives

To assess the long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets in people with hypertension on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, and adverse events (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events).

Secondary objectives

To assess the long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets in people with hypertension on change from baseline in systolic blood pressure, change from baseline in diastolic blood pressure, and body weight reduction.

Search methods

We obtained studies from computerised searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, Ovid MEDLINE, and Ovid EMBASE, and from searches in reference lists, systematic reviews, and the clinical trials registry ClinicalTrials.gov (status as of 2 February 2015).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of at least 24 weeks' duration that compared weight‐reducing dietary interventions to no dietary intervention in adults with primary hypertension.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias and extracted data. We pooled studies using fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. In case of moderate or larger heterogeneity as measured by Higgins I2, we used a random‐effects model.

Main results

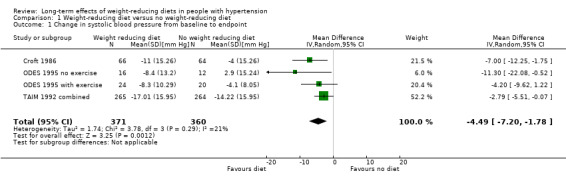

This review update did not reveal any new studies, so the number of included studies remained the same: 8 studies involving a total of 2100 participants with high blood pressure and a mean age of 45 to 66 years. Mean treatment duration was 6 to 36 months. We judged the risk of bias as unclear or high for all but two trials. No study included mortality as a predefined outcome. One RCT evaluated the effects of dietary weight loss on a combined endpoint consisting of the necessity of reinstating antihypertensive therapy and severe cardiovascular complications. In this RCT, weight‐reducing diet lowered the endpoint compared to no diet: hazard ratio 0.70 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.57 to 0.87). None of the studies evaluated adverse events as designated in our protocol. There was low‐quality evidence for a blood pressure reduction in participants assigned to weight loss diets as compared to controls: systolic blood pressure: mean difference (MD) ‐4.5 mm Hg (95% CI ‐7.2 to ‐1.8 mm Hg) (3 of 8 studies included in analysis), and diastolic blood pressure: MD ‐3.2 mm Hg (95% CI ‐4.8 to ‐1.5 mm Hg) (3 of 8 studies included in analysis). There was moderate‐quality evidence for weight reduction in dietary weight loss groups as compared to controls: MD ‐4.0 kg (95% CI ‐4.8 to ‐3.2) (5 of 8 studies included in analysis). Two studies used withdrawal of antihypertensive medication as their primary outcome. Even though we did not consider this a relevant outcome for our review, the results of these studies strengthen the finding of reduction of blood pressure by dietary weight loss interventions.

Authors' conclusions

In this update, the conclusions remain the same, as we found no new trials. In people with primary hypertension, weight loss diets reduced body weight and blood pressure, however the magnitude of the effects are uncertain due to the small number of participants and studies included in the analyses. Whether weight loss reduces mortality and morbidity is unknown. No useful information on adverse effects was reported in the relevant trials.

Plain language summary

Weight‐reducing diets for people with elevated blood pressure

Compared to the general population, people with high blood pressure have a higher risk of death and complications such as heart attack or stroke. Dietary interventions to lower body weight are commonly recommended as a first therapeutic step for overweight people with high blood pressure, based on the association of increased weight and increased blood pressure. However, whether weight loss has a long‐term effect on blood pressure and reduces the adverse effects of elevated blood pressure remains unclear.

As only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing groups with and without a weight‐reducing diet can answer these issues, we only included RCTs in our systematic review. Thirty articles reporting on eight studies met the inclusion criteria. The 8 included studies involved a total of 2100 participants with high blood pressure and a mean age of 45 to 66 years. Mean treatment duration was 6 to 36 months, and there was little or no information about deaths or other long‐term complications. Three of eight studies provided effects on systolic and diastolic blood pressure, suggesting that weight loss interventions reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 4.5 mm Hg and 3.2 mm Hg, respectively. Five out of eight studies reported body weight; weight loss interventions reduced weight by 4.0 kg as compared to controls. No useful information on adverse effects was reported in the included trials.

In conclusion, we found no evidence for effects of weight loss diets on death or long‐term complications and adverse events. Results on blood pressure and body weight should be considered uncertain, because not all studies were included in the analyses.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Weight‐reducing diets compared to no weight‐reducing diets for adults with essential hypertension | ||||

|

Patient or population: Men and non‐pregnant women ≥ 18 years old with essential hypertension Intervention: Weight‐reducing diets Comparison: No weight‐reducing diets | ||||

| Outcomes | Effect estimate (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Changes in systolic blood pressure [mm Hg] from baseline to end of study |

MD ‐4.49 (‐7.20 to ‐1.78) |

731 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Changes in diastolic blood pressure [mm Hg] from baseline to end of study |

MD ‐3.19 (‐4.83 to ‐1.54) |

731 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

|

Changes in body weight [kg] from baseline to end of study |

MD ‐3.98 (‐4.79 to ‐3.17) |

880 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Cardiovascular morbidity combined endpoint: necessity of reinstating antihypertensive therapy and severe cardiovascular complications Follow‐up: 30 months |

HR 0.70 (0.57 to 0.87) |

294 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Combined outcome includes events of much different severity |

| CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1High risk of bias in available randomised controlled trials.

2Wide confidence intervals.

3Only 1 randomised controlled trial.

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension is a chronic condition associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. It is estimated that high blood pressure leads to over 9 million deaths each year (WHO 2013). Lowering blood pressure levels in people with hypertension has been shown to be an effective means of reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Staessen 2005; Turnbull 2003).

Epidemiological investigations have consistently found an association between high blood pressure and different lifestyle factors, excess body weight among them (Kenchaiah 2002; Wannamethee 1996; Wilson 2002; Woodward 2005; Yusuf 2004). Some recently published systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) also supported this assumption, showing that weight loss intervention resulted in lower blood pressure (Aucott 2005; Dickinson 2006; Horvath 2008). High body weight is also associated with increased cardiovascular complications (Kenchaiah 2002; Wilson 2002). However, the observation that certain variables (for example excess body weight, high blood pressure) are quantitatively related to more cardiovascular events does not necessarily mean that lowering these variables will automatically reduce the number of cardiovascular events. This may be due to the fact that the variable in question (for example overweight) has no impact on aetiological pathways or that the damage to the cardiovascular system is already established and is only poorly or no longer reversible. It could also be the case that the treatment is effective and does lower cardiovascular events by reducing the risk factor, but at the same time increases cardiovascular or other risks through a different mechanism. To prove the effectiveness of an intervention, an RCT is required, for which, ideally, a protocol was published prospectively. Numerous interventions that have been recommended on the basis of associations found in epidemiological studies eventually failed to show any beneficial effect, and sometimes even did harm in subsequent RCTs, for example a large dietary‐intervention study of 8.1 years duration in 48,835 obese postmenopausal women (40% having hypertension) resulted in only a modest reduction in diastolic blood pressure and no significant reduction of any cardiovascular outcomes (Howard 2006).

Nevertheless, weight reduction is recommended in major guidelines as a first‐step intervention in the therapy of people with hypertension (CHEP 2014; ESH‐ESC 2013; JNC 2014; NICE 2011; WHO 2005). Body weight may be reduced by non‐pharmacological, pharmacological, or invasive interventions. A recently published Cochrane review of pharmacological interventions for weight reduction showed that orlistat reduced blood pressure and sibutramine increased blood pressure (Siebenhofer 2013). As of 2013, there were no RCTs testing the effect of invasive interventions in people with elevated blood pressure (Wilhelm 2014).

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the potential beneficial and harmful long‐term effects for people with hypertension who intend to reduce their body weight with non‐pharmacological dietary interventions.

Description of the intervention

This review covers dietary interventions (duration of at least 24 weeks) that aim to reduce body weight (for example dietary counselling, caloric restrictions, reduction in fat intake). We did not include other interventions such as exercise or other non‐drug approaches such as stress reduction techniques.

How the intervention might work

Observational studies of non‐pharmacological dietary measures in people with hypertension have suggested a positive association between body weight and blood pressure. One might therefore hypothesise that dietary intervention with the aim of reducing body weight would reduce blood pressure and adverse cardiovascular events in people with hypertension.

Why it is important to do this review

For overweight people with established hypertension, it is commonly recommended that blood pressure should first be managed by non‐pharmacological interventions, including weight reduction (CHEP 2014; ESH‐ESC 2013; JNC 2014; NICE 2011; WHO 2005). Since dietary interventions might support the efforts of patients to reduce body weight, it is important for the physician to be informed about the efficacy and potential harms of diets before recommending them.

Other reviews and meta‐analyses have shown that non‐pharmacological weight‐reducing interventions lead to reduction in blood pressure (Horvath 2008;IQWiG 2006). None of these reviews provided data to establish whether long‐term weight loss dietary interventions can lower the risk of mortality or cardiovascular morbidity.

This systematic review is an update of the previously published Cochrane review Siebenhofer 2011.

Objectives

Primary objectives

To assess the long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets in people with hypertension on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, and adverse events (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events).

Secondary objectives

To assess the long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets in people with hypertension on change from baseline in systolic blood pressure, change from baseline in diastolic blood pressure, and body weight reduction.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs of at least 24 weeks’ duration that compared weight‐reducing dietary interventions to no dietary intervention in adults with primary hypertension. Any additional pharmacological or non‐pharmacological co‐intervention must have been administered to all randomised participants and must not have been significantly different for the treatment and control groups at baseline or during the duration of the trial.

For example, we did not include a randomised trial with exercise plus diet versus no treatment. A trial in which all randomised participants exercised, and the only difference was weight‐reducing diet versus no treatment or placebo would have met the inclusion criteria.

Types of participants

We included men and non‐pregnant women 18 years of age or older with essential hypertension (defined as baseline systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg and/or baseline diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg or people on antihypertensive treatment).

Types of interventions

Dietary intervention with the intention to reduce body weight in comparison with no dietary intervention to reduce body weight.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

total mortality

cardiovascular morbidity

adverse events (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events)

Secondary outcomes

change from baseline in systolic blood pressure

change from baseline in diastolic blood pressure

change in body weight

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) for related reviews up to March 2015.

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) , the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (up to March 2015), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (up to March 2015), Ovid MEDLINE (1966 to February 2015), and Ovid EMBASE (1988 to February 2015) to identify relevant randomised controlled trials.

We searched the following databases for primary studies: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register (all years to February 2015), CENTRAL via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (2015, Issue 2), Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to February 2015), Ovid EMBASE (1980 to February 2015) and ClinicalTrials.gov (all years to February 2015).

We translated the MEDLINE search strategy into the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, CENTRAL, and EMBASE, using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable (Appendix 1). The search strategy used in the original review is documented in Appendix 2. The Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register includes searches of the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of all papers and relevant reviews identified.

Authors of relevant papers were contacted regarding any further published or unpublished work.

Authors of trials reporting incomplete information were contacted to provide the missing information.

Clinical trials registry: ClinicalTrials.gov.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the title and abstract of each reference identified by the search and applied the inclusion criteria. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and again two review authors independently decided, whether these studies met the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, we also obtained the full article and the two review authors inspected it independently. A third review author resolved disagreements. If a resolution of the disagreement was not possible, we added the article to those 'awaiting assessment' and contacted the authors of the study for clarification. We re‐assessed the articles after receiving the authors' replies.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from each included study using a standardised data extraction form. Differences in data extraction were resolved by consensus, referring back to the original article. If necessary, we sought information from the authors of the primary studies. We extracted, checked, and recorded the following data.

General information including the sponsor of the trial (specified, known, or unknown) and country of publication.

All characteristics of the trial, participants, interventions, and outcome measures were summarised as reported in the publication.

Characteristics of the trial comprised the study design, duration of the trial, method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, people administering treatment, outcome assessors) and testing of blinding. We reported the characteristics of randomised participants at baseline and checked the similarity of groups at baseline.

Characteristics of participants are summarised in the Characteristics of included studies table and comprise the number of participants in each group, how the participants were selected (random), exclusion criteria used, and general characteristics (e.g. age, gender, nationality, ethnicity).

Relevant information regarding duration of the intervention, length of follow‐up (in months), and types of dietary weight‐reducing interventions.

Data of outcome measures concerning total mortality, cardiovascular morbidity (including stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, etc.), total serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, total non‐serious adverse events, mean change from baseline in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as change in body weight.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed trials meeting the inclusion criteria to evaluate methodological quality. Any differences in opinion were resolved by discussion with a third review author. We assessed all trials meeting the inclusion criteria using the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool under the categories adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases (Higgins 2011).

We carefully evaluated important numerical data such as screened, eligible, and randomised patients, as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT) and per‐protocol (PP) population. We investigated attrition rates, for example dropouts, losses to follow‐up, and withdrawals. Issues of missing data, ITT, and PP were critically appraised and compared to specifications for primary outcome parameters and power calculation.

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratio with 95% confidence interval for dichotomous variables such as total mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, total withdrawals, and withdrawals due to adverse events. We calculated mean difference for the mean change in systolic as well as diastolic blood pressure and body weight between the groups. If the standard deviation of the mean change was not explicitly given in the study, it was calculated from confidence intervals and standard error of the mean or estimated from P values.

The position of the patient during blood pressure measurement may affect the blood pressure‐lowering effect. When measurements were reported for more than one position, the order of preference was: 1) sitting; 2) standing; and 3) supine (Musini 2009).

Dealing with missing data

If necessary, we contacted authors of trials reporting incomplete information to provide the missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using Higgins I2. In the case of substantial heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we had planned to perform sensitivity and subgroup analyses for the following items: study quality, PP versus ITT analyses, sex, age, body mass index, concomitant diseases, ethnicity, blood pressure at baseline, blood pressure goals, concomitant antihypertensive therapy, and socioeconomic status.

Assessment of reporting biases

We tested publication bias and small‐study effects in general using the funnel plot or other corrective analytical methods depending on the number of clinical trials included in the systematic review.

Data synthesis

We summarised data statistically if they were available, sufficiently similar, and of adequate quality. We performed data synthesis and analyses using the Cochrane Review Manager software, Review Manager 5. We performed statistical analysis according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We used fixed‐effects model for the meta‐analyses. In case of moderate or larger heterogeneity as measured by Higgins I2, random‐effects model was used and presented.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses where appropriate. Heterogenity among participants could be related to, for example, sex, age, body mass index, concomitant diseases, ethnicity, blood pressure at baseline, blood pressure goals, concomitant antihypertensive therapy, and socioeconomic status.

Sensitivity analysis

We tested robustness of results where appropriate using several sensitivity analyses (for example study quality or PP versus ITT analyses, studies with large drop‐out rates and losses to follow‐up).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

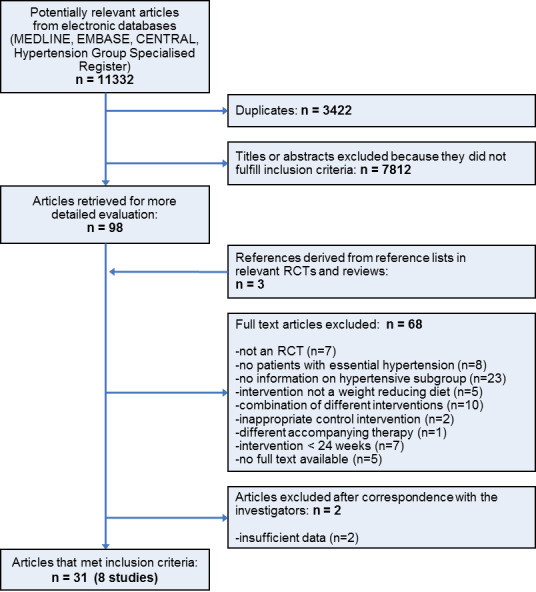

Our search of the electronic databases yielded 11,332 records, of which 3422 could be excluded as duplicates. Of the remaining 7910 publications, we excluded 7812 by consensus as not relevant to the question under study on the basis of their abstracts. In addition, we identified one study among the references of a report of the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG 2006), and found two further articles in the reference lists of included trials and relevant reviews, resulting in 101 articles for further examination. After screening the full texts of these publications, we found 31 articles on 8 studies that met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for details of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) statement (PRISMA 2009)).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We have provided details of the characteristics of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table. The following gives a brief overview of the comparisons between dietary interventions with an intention to reduce body weight and no dietary interventions to reduce body weight.

All eight included studies had a parallel and open design (Cohen 1991; Croft 1986; DISH 1985; Jalkanen 1991; ODES 1995; Ruvolo 1994; TAIM 1992; TONE 1998), and three of them had a factorial design (ODES 1995; TAIM 1992; TONE 1998). Four studies were performed as single‐centre trials (Cohen 1991; Croft 1986; ODES 1995; Ruvolo 1994), and three did not mention any industry sponsoring (Cohen 1991; Jalkanen 1991; Ruvolo 1994).

Participants and duration

The included studies involved a total of 2100 hypertensive participants with a mean age of 45 to 66 years, a baseline systolic blood pressure of 128 to 178 mm Hg, and a baseline diastolic blood pressure of 72 to 107 mm Hg. Mean treatment duration was 6 to 36 months.

Interventions

In all studies, participants received either a dietary intervention with the aim of reducing body weight or no dietary intervention to reduce body weight.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Only one study included the occurrence of clinical cardiovascular disease complications during follow‐up as a predefined outcome (TONE 1998). Two studies reported adverse events (DISH 1985; TONE 1998).

Secondary outcomes

Except for three studies (Cohen 1991; DISH 1985; TONE 1998), all included studies described the mean change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. All but one study, TONE 1998, described mean change in body weight.

Excluded studies

The main reason for exclusion was a lack of sufficient results for the hypertensive subgroup in studies including normotensive as well as hypertensive participants. We excluded some studies because they were not randomised controlled trials, did not include participants with essential hypertension, did not aim for weight reduction or examined a combined intervention, provided an inappropriate control intervention or different accompanying therapies, had a duration of intervention less than 24 weeks, or full text was not available. We excluded two studies after personal communication (Curzio 1989; Haynes 1984). Both studies were performed in the 1980s, and electronic records and/or hard copies were no longer available to further clarify whether the studies were suitable for inclusion in our review. We have provided reasons for excluding each trial in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

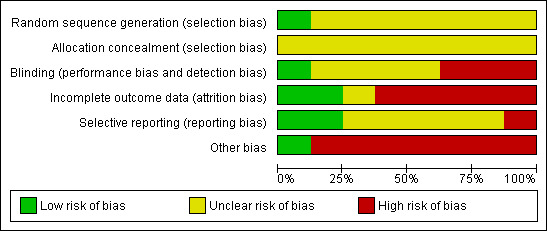

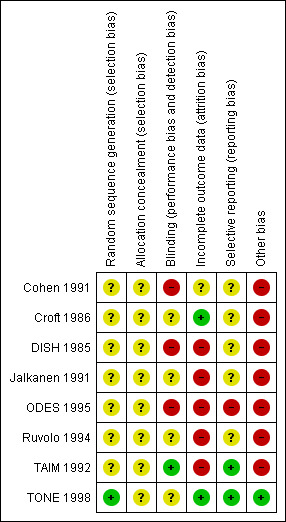

Risk of bias in included studies

Our judgements of the risk of bias for all included studies are shown in the 'Risk of bias' summary figures (Figure 2; Figure 3). For details, see the 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies. The following gives a brief overview.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Only two studies reported the method of randomisation (TAIM 1992; TONE 1998), and both of them had a factorial design. Only one study described the method of concealment (TAIM 1992). One study performed a cluster randomised trial in family practices (Cohen 1991), but without providing any information on allocation.

Blinding

All included trials had an open design in terms of participants and study personnel. In one study (TONE 1998), an independent committee masked to intervention assignment evaluated the endpoints. In another study (TAIM 1992), blood pressure endpoint assessment was blinded in only one out of three clinical centres due to logistical and budgetary considerations.

Incomplete outcome data

In one study (Cohen 1991), the description of the outcome data was complete because there were no losses to follow‐up. In DISH 1985, no withdrawals were reported for the endpoint success of withdrawal from antihypertensive medication, but between 13% and 23% of values were missing for body weight at follow‐up. In Jalkanen 1991 and Ruvolo 1994, only one to two participants were missing, but no reason for withdrawal was given. In TAIM 1992 and ODES 1995, study withdrawals were only reported for the whole study population, and no intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. In TONE 1998, numbers of and reasons for withdrawals were missing, but 96% to 99% of participants were included in the follow‐up analysis.

Selective reporting

There was a risk of selective reporting bias in one study in which post‐hoc analyses of blood pressure were calculated, and results were not reported for all predefined outcomes (ODES 1995).

Other potential sources of bias

We could identify other potential sources of bias in all except one study (TONE 1998). One study featured stratified randomisation of investigators instead of participants, with very small cluster size (Cohen 1991). In another study (DISH 1985), participants were randomised before consent was obtained, and in two studies (Cohen 1991; TAIM 1992), treatment in the intervention group seemed to be more intensive. For further details, please see the 'Risk of bias' table and Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Mortality

None of the included studies was designed to evaluate the effects of weight loss diet versus no diet on mortality.

Cardiovascular morbidity

Only one study evaluated the effects of dietary weight loss intervention versus no dietary intervention, on a combined endpoint including cardiovascular complications (TONE 1998). After 30 months, the hazard ratio for participants in the dietary group to reach the combined endpoint, consisting of the necessity of reinstating antihypertensive therapy and severe cardiovascular complications, was 0.70 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57 to 0.87) compared with participants in the usual‐care group.

Adverse events

None of the included studies evaluated the endpoint adverse event as designed in our protocol (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events).

TONE 1998 classified adverse events by type (primary cardiovascular events) and time of occurrence (before, during, or after attempted antihypertensive drug withdrawals). However, no usable results were reported for the obese subgroups with and without dietary interventions. DISH 1985 reported adverse events as withdrawals due to the need to resume antihypertensive medication; this was the case in 40.5% of participants in the intervention group and 64.7% of participants in the control group (P = 0.0015).

Secondary outcomes

For details on secondary outcome data, see Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5. Due to between‐study variability, we have presented results from random‐effects models in the following analyses.

1. Body weight.

| Study | Body weight [kg]a | ||||

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | > 12 months | Change (baseline to endpoint) | |

| Cohen 1991 IG CG |

92b 92b |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c |

‐0.9 (4.0) vs +1.3 (3.0); P < 0.1 |

| Croft 1986 IG CG |

87 (4) 82 (3) |

80 (4) 82 (3) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐6.5b vs ‐0.2b; P < 0.001 |

| Jalkanen 1991 IG CG |

86 (14) 80 (11) |

n. r. n. r. |

82 (13) 80 (11) |

‐c ‐c |

‐4.0d vs 0.0d; P < 0.05 |

| DISH 1984 to 1985 IG CG |

86 (17) 90 (18) |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c |

‐4.0 (5.0) vs ‐0.5 (3.6); P < 0.05e |

| ODES 1993 to 2001f | n. r. | n. r. | n. r. | n. r. | n. r. |

| Ruvolo 1994 IG CG |

98 (8) 97 (8) |

84 (9) 95 (8) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐14b,g vs ‐2b,g; n. r. |

| TAIM 1989 to 1994 IG‐P CG‐P IG‐A CG‐A IG‐C CG‐C |

90b 86b 86b 89b 87b 89b |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h |

‐4.4 (0.7)j vs ‐0.7 (0.4)j; n. r. ‐3.0 (0.4)j vs +0.5 (0.3)j; n. r. ‐6.9 (0.5)j vs ‐1.5 (0.4)j; n. r. |

| TONE 1995 to 2002 IG‐S‐ CG‐S‐ IG‐S+ CG‐S+ |

87 (10) 86 (10) 86 (10) 88 (11) |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r.k n. r.k n. r.k n. r.k |

aMean (standard deviation), unless otherwise indicated.

bData on variance missing.

cObservation period ≤ 12 months.

dNumbers calculated from the tables of publications. A mean weight reduction of 5 kg is stated in the text section.

eInformation on body weight was available for 77% of participants in the intervention group and 87% of participants in the control group.

fNot mentioned for the hypertensive subgroup.

gCalculated from table 1 in Ruvolo 1994.

hOnly change in body weight reported for 24 months; since no other outcomes were reported for this time, and change in body weight is not a primary endpoint of this report, data were not extracted.

jStandard error.

kWeight reduction of 3.9 vs 0.9 kg (P < 0.001) in overweight participants of both intervention groups together (with and without salt restriction) vs control group.

[CG]: control group. [CG‐A]: control group + atenolol. [CG‐C]: control group + chlortalidone. [CG‐P]: control group + placebo. [CG‐S+]: control group + salt restriction. [CG‐S‐]: control group without salt restriction. [IG]: intervention group. [IG‐A]: intervention group + atenolol. [IG‐C]: intervention group + chlortalidone. [IG‐P]: intervention group + placebo. [IG‐S+]: intervention group + salt restriction. [IG‐S‐]: intervention group without salt restriction. [n. r.]: not reported.

2. Systolic blood pressure.

| Study | Systolic blood pressure [mm Hg]a | ||||

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | > 12 months | Change (baseline to endpoint) | |

| Cohen 1991 IG CG |

n. r.b n. r.b |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c |

n. r.b n. r.b |

| Croft 1986 IG CG |

161 (4) 161 (4) |

150 (4) 157 (4) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐11.0d vs ‐4.0d; P < 0.01 |

| Jalkanen 1991 IG CG |

152 (17) 155 (14) |

n. r. n. r. |

144 (20) 140 (16) |

‐c ‐c |

‐8.0d vs ‐15.0d; n. r. |

| DISH 1984 to 1985 | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e |

| ODES 1993 to 2001 IG CG IG‐KA+ CG‐KA+ |

145 (5)f 138 (3)f 143 (2)f 140 (2)f |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c ‐c ‐c |

‐8.4 (3.3)f vs 2.9 (4.4)f; P < 0.05 ‐8.3 (2.1)f vs ‐4.1 (1.8)f; n. r. |

| Ruvolo 1994 IG CG |

178 (8) 176 (8) |

145 (6) 144 (6) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐33d,g vs ‐32d,g; n. r. |

| TAIM 1989 to 1994 IG‐P CG‐P IG‐A CG‐A IG‐C CG‐C |

143d 145d 143d 143d 141d 142d |

n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h n. r.h |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

‐11.5d vs ‐10.3d; n. r. ‐18.1d vs ‐15.1d; n. r. ‐21.7d vs ‐17.4d; n. r. |

| TONE 1995 to 2002 | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e |

aMean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

bOnly the mean arterial blood pressure is reported (at baseline: IG and CG 106 mm Hg each; change from baseline to endpoint: IG +3.0 (SD 14.2) mm Hg and CG ‐0.7 (SD 11.3) mm Hg).

cObservation period ≤ 12 months.

dData on variance missing.

ePurpose of the study was not the change in blood pressure, but the number of participants without any antihypertensive drug requirements at the end of the study after successful withdrawal of antihypertensives.

fStandard error.

gCalculated from table 1 in Ruvolo 1994.

hOnly changes from baseline are reported, no absolute values.

[CG]: control group. [CG‐A]: control group + atenolol. [CG‐C]: control group + chlortalidone. [CG‐P]: control group + placebo. [CG‐PA+]: control group + physical activity. [IG]: intervention group. [IG‐A]: intervention group + atenolol. [IG‐C]: intervention group + chlortalidone. [IG‐P]: intervention group + placebo. [IG‐PA+]: intervention group + physical activity. [n. r.]: not reported. [SD]: standard deviation.

3. Diastolic blood pressure.

| Study | Diastolic blood pressure [mm Hg]a | ||||

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | > 12 months | Change (baseline to endpoint) | |

| Cohen 1991 IG CG |

n. r.b n. r.b |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c |

n. r.b n. r.b |

| Croft 1986 IG CG |

98 (2) 96 (2) |

91 (2) 95 (2) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐7.0d vs ‐1.0d; P < 0.001 |

| Jalkanen 1991 IG CG |

101 (8) 102 (7) |

n. r. n. r. |

90 (10) 91 (7) |

‐c ‐c |

‐11.0d vs ‐11.0d; n. r. |

| DISH 1984 to 1985 | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e |

| ODES 1993 to 2001 IG CG IG‐ KA+ CG‐ KA+ |

97 (1)f 96 (1)f 97 (1)f 96 (1)f |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. n. r. n. r. |

‐c ‐c ‐c ‐c |

‐7.1 (1.8)f vs ‐0.4 (3.6)f; ns ‐7.1 (1.3)f vs ‐5.5 (1.7)f; n. r. |

| Ruvolo 1994 IG CG |

107 (5) 106 (5) |

84 (4) 85 (5) |

‐c ‐c |

‐c ‐c |

‐23d,g vs ‐21d,g; n. r. |

| TAIM 1989 to 1994 IG CG |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r.h n. r.h |

n. r. n. r. |

n. r. n. r. |

‐12.8 (10.0) vs ‐10.4 (7.8); P = 0.001i |

| TONE 1995 to 2002 | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e | ‐e |

aMean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

bOnly the mean arterial blood pressure is reported (at baseline: IG and CG 106 mm Hg each; change from baseline to endpoint: IG +3.0 (SD 14.2) mm Hg and CG ‐0.7 (SD 11.3) mm Hg).

cObservation period ≤ 12 months.

dData on variance missing.

ePurpose of the study was not the change in blood pressure, but the number of participants without any antihypertensive drug requirements at the end of the study after successful withdrawal of antihypertensives.

fStandard error.

gCalculated from table 1 in Ruvolo 1994.

hOnly changes from baseline are reported, no absolute values.

iP = 0.002 reported in another publication.

[CG]: control group. [CG‐A]: control group + atenolol. [CG‐C]: control group + chlortalidone. [CG‐P]: control group + placebo. [CG‐PA+]: control group + physical activity. [IG]: intervention group. [IG‐A]: intervention group + atenolol. [IG‐C]: intervention group + chlortalidone. [IG‐P]: intervention group + placebo. [IG‐PA+]: intervention group + physical activity. [n. r.]: not reported. [ns]: not significant. [SD]: standard deviation.

Changes in systolic blood pressure

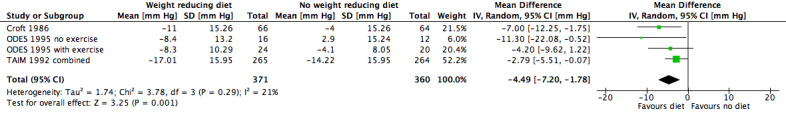

Five studies investigating the effects of dietary versus no dietary intervention could not be included in the meta‐analysis for systolic blood pressure. In two studies (DISH 1985; TONE 1998), successful withdrawal from antihypertensives was the primary outcome. In another study (Cohen 1991), only the mean blood pressure change was reported, and in the studies of Ruvolo and Jalkanen (Jalkanen 1991; Ruvolo 1994), estimators for variance and P values for the change in systolic blood pressure were missing. Therefore, only three studies remained for analysis; in the case of the TAIM study (TAIM 1992), the overall standard deviation (SD) presented for the combined analyses could be used for the meta‐analysis. There was a significant reduction of systolic blood pressure with a mean difference (MD) of ‐4.5 mm Hg (95% CI ‐7.2 to ‐1.8) in favour of dietary intervention. The test of heterogeneity gave a P value of 0.3, and Higgins I2 indicated only low heterogeneity between studies (I2= 21%) (see Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). Differences in study quality could not explain heterogeneity. We could deduce no plausible explanation for heterogeneity from differences in study design, study duration, sample sizes, interventions, or characteristics of included participants.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, Outcome 1 Change in systolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, outcome: 1.1 Change in systolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint [mm Hg].

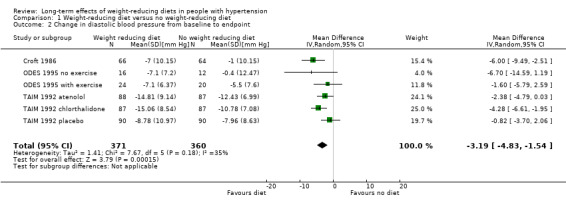

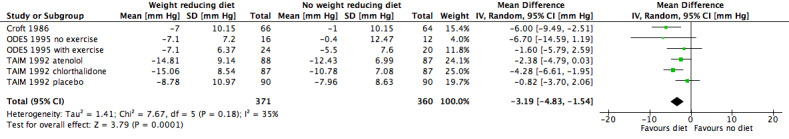

Changes in diastolic blood pressure

Five studies investigating the effects of dietary versus no dietary intervention could not be included in the meta‐analysis for diastolic blood pressure. In two studies (DISH 1985; TONE 1998), successful withdrawal from antihypertensives was the primary outcome. In another study (Cohen 1991), only the mean blood pressure change was reported, and Jalkanen 1991 and Ruvolo 1994 do not include an estimator for variance and P values for the change in diastolic blood pressure. Therefore, only three studies remained for analysis; in the case of the TAIM study (TAIM 1992), the SDs presented for the subgroup (atenolol, chlorthalidone, placebo) analyses could be used for the meta‐analysis. There was a significant reduction of diastolic blood pressure with a MD of ‐3.2 mm Hg (95% CI ‐4.8 to ‐1.5) in favour of dietary intervention. The test of heterogeneity gave a P value of 0.2 (I2 = 35%) (see Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). Differences in study quality could not explain heterogeneity. We could deduce no plausible explanation for heterogeneity from differences in study design, study duration, sample sizes, interventions, or characteristics of included participants.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, Outcome 2 Change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, outcome: 1.2 Change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint [mm Hg].

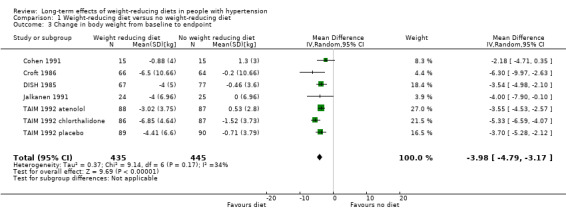

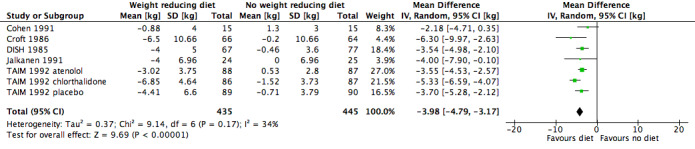

Body weight

Only three studies investigating the effects of dietary versus no dietary intervention could not be included in the meta‐analysis for body weight. In two studies (ODES 1995; TONE 1998), no values for changes in body weight were presented, and in the study of Ruvolo (Ruvolo 1994), an estimator for variance and P values for the change in body weight was missing. Therefore, five studies remained for analysis. In the TAIM study (TAIM 1992), we could use the SDs presented for the subgroup (atenolol, chlorthalidone, and placebo) analyses. Dietary intervention was found to lower body weight significantly more effectively with a MD of ‐4.0 kg (95% CI ‐4.8 to ‐3.2) in favour of dietary intervention. The test of heterogeneity gave a P value of 0.2 (I2 = 34%) (see Analysis 1.3; Figure 6). Differences in study quality could not explain heterogeneity. We could deduce no plausible explanation for heterogeneity from differences in study design, study duration, sample sizes, interventions, or characteristics of included participants.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, Outcome 3 Change in body weight from baseline to endpoint.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet, outcome: 1.3 Change in body weight from baseline to endpoint [kg].

Subgroup analyses

Not performed due to lack of data.

Sensitivity analyses

Not performed due to lack of data.

Publication and small‐study bias

A clear interpretation of the funnel plot was not possible, which we mainly attributed to the relatively small number of included studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This updated systematic review attempted to determine the long‐term effects of weight loss through dietary interventions on patient‐relevant endpoints, namely death, cardiovascular complications, and adverse events, in the antihypertensive therapy of people with essential hypertension. However, we found no currently available randomised controlled trials designed to answer this question. We identified no new studies as a result of the update and eight relevant trials that intended to reduce body weight (for example dietary counselling, caloric restrictions, reduction in fat intake) versus no dietary interventions. Of the eight included studies, only two were judged as having minor deficiencies of study quality (TAIM 1992; TONE 1998), while the other six studies have major deficiencies. Only one study reported on cardiovascular complications, as part of a combined primary outcome consisting of the necessity of reinstating antihypertensive therapy and severe cardiovascular complications, and was in favour of the dietary‐intervention group (TONE 1998). No valuable information on adverse effects was reported in any publications on the relevant trials. The meta‐analyses showed that participants under dietary therapy could reduce their systolic and diastolic blood pressure and body weight levels statistically significantly more than participants in the control groups.

Two studies did not aim for blood pressure reduction, but used successful withdrawal of antihypertensive medication as primary outcomes (DISH 1985; TONE 1998). In DISH 1985, about 35% of the participants in the control group and about 60% in the intervention group remained without antihypertensive medication after 56 weeks. In TONE 1998, 93% of the participants in the weight loss group and 87% in the control group could stop antihypertensive treatment. In the salt‐lowered groups, 93% of both the dietary weight loss intervention and the usual‐care group could successfully be taken off medication. Even though successful withdrawal of antihypertensive treatment was not included as a chosen outcome in our review, it further underscores the success of dietary weight loss interventions for reducing blood pressure.

In conclusion, in people with essential hypertension, therapy with dietary interventions to reduce body weight resulted in reductions in blood pressure and body weight. A reduction in body weight of approximately 4 kg was necessary to achieve a reduction of approximately 4.5 mm Hg systolic blood pressure and approximately 3.2 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure. However, the fact that only some of the studies could be included in the analyses weakens our conclusion. None of the studies provided data to answer the question of whether weight reduction can lower the risk of mortality or other patient‐relevant endpoints.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We searched four electronic databases and the clinical trials registry ClinicalTrials.gov until 2 February 2015. We also searched the reference lists of included trials and relevant systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. We assessed the quality of each study and summarised the results. The results of this review can therefore be taken to be complete and applicable. For full information, please see details in the relevant sections.

While the results of this review show that dietary interventions may be helpful in the antihypertensive therapy of overweight hypertensive patients, major questions still remain. One point raised by Brian Haynes, a co‐author we contacted for further clarification on whether his paper was relevant for inclusion in the review, was whether any effect on blood pressure lowering persists when the patient's period of active weight loss ends. His clinical impression is that when weight loss stops (even if the weight loss is maintained?), the blood pressure goes back up (Haynes 2010 [pers comm]). However, as we could identify no long‐term follow‐up trials for our review, the long‐term effects of weight loss on blood pressure are uncertain. Indirect evidence from this assumption can be derived from the Swedish Obese Subject Study (Sjostrom 2004), where participants successfully reduced their body weight by means of bariatric surgery. This study showed that the postsurgical blood pressure reduction was still present 2 years after surgery, but increased again to baseline values after 10 years, despite continued weight loss. Secondly, it can be asked whether people with higher or lower blood pressure or higher or lower body weight at baseline might benefit in a different way from dietary intervention aiming to reduce body weight. It can, however, be assumed that the potential benefit on blood pressure might be greater in people with moderate to severe hypertension than in people with mild hypertension; in any case, no correlation could be identified from the included studies.

Quality of the evidence

Of the eight studies included in our analyses, we judged only two as having minor deficiencies of quality (TAIM 1992; TONE 1998). All other studies have to be judged as having major deficiencies. Therefore, the beneficial effects shown reflect some degree of uncertainty. We have provided full details in the 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies.

Potential biases in the review process

A major limitation of this review is that due to the lack of information in the included studies, we could draw no conclusions on the effects of the different dietary weight loss interventions on patient‐relevant long‐term outcomes.

The results for the change in blood pressure outcomes could also be considered uncertain as data from only three studies were included in the analyses. These results were mainly based on the TAIM 1992 study, which we judged to have a low risk of bias and contributed more than 70% of all participants to the meta‐analyses. In addition, two of the trials that did not report results on blood pressure showed a reduction of antihypertensive medication as an indirect measure of blood pressure, which supports the findings of our meta‐analyses. Furthermore, inclusion of the remaining studies from which data on blood pressure were available but were insufficient would probably not have changed the results because these studies were all small and rated as at high risk of bias.

The findings on body weight may also be regarded as uncertain as results from only five studies were available for the analysis. Again, the TAIM 1992 study had the highest weight in the analysis. These results are supported by results from the ODES 1995 study, which did not report on body weight, but found body mass index to be reduced to a greater extent among participants in the intervention groups.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are only a few published systematic reviews on long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets in people with hypertension. One systematic review, 'Effects of Weight Loss in Overweight/Obese Individuals and Long‐Term Hypertension Outcomes', published by Aucott (Aucott 2005), reached the same conclusion, that is that only short‐term trials were available. The authors also warned "that extrapolation of short‐term blood pressure changes with weight loss to the longer term is potentially misleading. The weight/hypertension relationship is complex and needs well‐conducted studies with long‐term follow‐up to examine the effects of weight loss on hypertension outcomes". In addition, we were involved in the preparation of the scientific report on the evaluation of the benefits and harms of non‐drug treatment strategies in people with essential hypertension (IQWiG 2006), and published a paper on this topic in 2008 (Horvath 2008). Since our last search for dietary interventions performed on 22 November 2010 (Siebenhofer 2011), we could identify no new trials addressing our research question. We can therefore say with confidence that our findings are in agreement with other published reviews and studies in this field.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although trials on dietary interventions in people with elevated blood pressure demonstrated statistically significant decreases in weight loss and blood pressure, these findings are subject to a high risk of selective reporting bias. Furthermore, the available randomised controlled trial evidence provided no data on the effect of dietary interventions on mortality and morbidity, and none of the included trials reported valuable information on adverse events.

Implications for research.

Long‐term trials assessing the effect of dietary interventions to reduce body weight on mortality, morbidity, and adverse events in people with elevated blood pressure are needed. Long‐term follow‐up data are also needed to determine the long‐term effects of weight‐reducing diets on blood pressure.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 February 2016 | New search has been performed | We updated the search for new studies in February 2015. We identified no new studies that met the inclusion criteria of this review. We have added a 'Summary of findings' table. |

| 2 February 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Update published with changed authors, updated search, conclusions not changed. |

Acknowledgements

The review authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Jutta Meschik in reviewing the data and Douglas Salzwedel for assisting in updating the literature search for the 2015 update of this review.

The review authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Eva Matyas, Nicole Pignitter, and Anika Maas in reviewing the data and the contribution of Eugenia Lamont in the final editing of the manuscript for the 2011 version of this review.

The review authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Andreas Waltering, Lars Hemkens, Christoph Pachler, and Reinhard Strametz in the selection of studies, quality assessment of trials, data extraction, and development of the final 2011 version of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search Date: 2 February 2015 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 (adipos$ or antiadipos$ or antiobes$ or bodyweight or obes$ or overweight or weight$).mp. (1095649) 2 (aliment$ or diet$ or eat$ or fare or feed$ or food$ or nourishment$ or nutrit$).mp. (1184712) 3 hypertension/ (193098) 4 (antihypertens$ or hypertens$).ti,ab,ot. (316377) 5 exp blood pressure/ (247959) 6 (blood pressure$ or bloodpressure$).ti,ab,ot. (216221) 7 or/3‐6 (592086) 8 randomized controlled trial.pt. (382126) 9 pragmatic clinical trial.pt. (94) 10 controlled clinical trial.pt. (88433) 11 randomized.ab. (280881) 12 placebo.ab. (147976) 13 clinical trials as topic/ (170476) 14 randomly.ab. (199395) 15 trial.ti. (120826) 16 or/8‐15 (875513) 17 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) (3883708) 18 16 not 17 (803039) 19 1 and 2 and 7 and 18 (2713) 20 remove duplicates from 19 (2688) *************************** Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2015, Issue 1 via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online Search Date: 4 February 2015 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1(adipos* or antiadipos* or antiobes* or bodyweight or obes* or overweight or weight*)56301 #2(aliment* or diet* or eat* or food* or nourishment* or nutrit*)65236 #3antihypertens* or hypertens*35510 #4(elevat* OR lower* OR high OR raised) AND (blood pressure OR bloodpressure or bp) 20239 #5#3 OR #446939 #6#1 AND #2 AND #52015 ***************************

Database: Embase <1974 to 2015 February 03> Search Date: 4 February 2015 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 (adipos$ or antiadipos$ or antiobes$ or bodyweight or obes$ or overweight or weight$).mp. (1468599) 2 (aliment$ or diet$ or eat$ or fare or feed$ or food$ or nourishment$ or nutrit$).mp. (1685480) 3 exp hypertension/ (514055) 4 (antihypertens$ or hypertens$).ti,ab,ot. (466888) 5 exp blood pressure/ (415262) 6 (blood pressure$ or bloodpressure$).ti,ab,ot. (302279) 7 or/3‐6 (973509) 8 randomized controlled trial/ (360388) 9 crossover procedure/ (41301) 10 double‐blind procedure/ (119849) 11 (randomi?ed or randomly).tw. (755175) 12 (crossover$ or cross‐over$).tw. (73881) 13 placebo.ab. (204813) 14 (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. (153334) 15 assign$.ab. (247698) 16 allocat$.ab. (87318) 17 or/8‐16 (1153398) 18 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) (5532735) 19 17 not 18 (1002841) 20 1 and 2 and 7 and 19 (5427) 21 remove duplicates from 20 (5364) *************************** Database: Hypertension Group Specialised Register Search Date: 4 February 2015 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ #1 (adipos* or antiadipos* or antiobes* or bodyweight or obes* or overweight or weight*)8310 #2 (aliment* or diet* or eat* or food* or nourishment* or nutrit*)7456 #3 antihypertens* or hypertens*32571 #4 (elevat* OR lower* OR high OR raised) AND (blood pressure OR bloodpressure or bp) 16739 #5 #3 OR #4 38956 #6 (RCT OR Review OR Meta‐Analysis):DE 22333 #7 #1 AND #2 AND #5 AND #6 1361 *************************** Database: ClinicalTrials.gov (via Cochrane Register of Studies) Search Date: 4 February 2015 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Search terms: randomized AND (bodyweight OR overweight OR weight) Study type: Interventional Studies Conditions: hypertension Intervention: dietary (113) ***************************

Appendix 2. Search strategies used in original review

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1966 to Present with Daily Update

Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp hypertension/ or exp blood pressure/ 2 (hypertens$ or antihypertens$ or anti hypertens$).ti,ab,ot. 3 ((systolic or diastolic or arterial) adj pressur$).ti,ab,ot. 4 (blood pressur$ or bloodpressur$).ti,ab,ot. 5 or/1‐4 6 (weigh$ or overweight or bodyweight or obes$ or adipos$ or antiobes$ or antiadipos$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 7 (diet$ or nutriti$ or food$ or feed$ or fare or eat$ or nourishment$ or aliment$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 8 exp nutrition therapy/ 9 or/7‐8 10 and/5‐6,9 11 controlled clinical trial.pt. 12 exp Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic/ 13 randomized controlled trial.pt. 14 Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/ 15 random allocation/ 16 cross‐over studies/ 17 Double‐Blind Method/ 18 Single‐Blind Method/ 19 or/11‐18 20 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj6 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab,ot. 21 ((random$ or cross‐over or crossover) adj25 (trial$ or study or studies or intervention$ or investigat$ or experiment$ or design$ or method$ or group$ or evaluation$ or evidenc$ or data or test$ or condition$)).ti,ab,ot. 22 (random$ adj25 (cross over or crossover)).ti,ab,ot. 23 (RCT or placebo$).ti,ab,ot. 24 or/20‐23 25 19 or 24 26 Animals/ 27 Humans/ 28 26 not 27 29 25 not 28 30 10 and 29

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Database: EMBASE (Ovid) <1988 to 2010> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 exp hypertension/ or exp blood pressure/ 2 (hypertens$ or antihypertens$ or anti hypertens$).ti,ab,ot. 3 ((systolic or diastolic or arterial) adj pressur$).ti,ab,ot. 4 (blood pressur$ or bloodpressur$).ti,ab,ot. 5 or/1‐4 6 (weigh$ or overweight or bodyweight or obes$ or adipos$ or antiobes$ or antiadipos$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 7 (diet$ or nutriti$ or food$ or feed$ or fare or eat$ or nourishment$ or aliment$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 8 exp nutrition/ 9 or/7‐8 10 and/5‐6,9 11 controlled clinical trial/ 12 randomized controlled trial/ 13 randomization/ 14 crossover procedure/ 15 double blind procedure/ 16 single blind procedure/ 17 or/11‐16 18 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj6 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab,ot. 19 ((random$ or cross‐over or crossover) adj25 (trial$ or study or studies or intervention$ or investigat$ or experiment$ or design$ or method$ or group$ or evaluation$ or evidenc$ or data or test$ or condition$)).ti,ab,ot. 20 (random$ adj25 (cross over or crossover)).ti,ab,ot. 21 (RCT or placebo$).ti,ab,ot. 22 or/18‐21 23 17 or 22 24 animal/ not human/ 25 23 not 24 26 10 and 25

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Database: EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid) <4th Quarter 2010> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp hypertension/ or exp blood pressure/ 2 (hypertens$ or antihypertens$ or anti hypertens$).ti,ab,ot. 3 ((systolic or diastolic or arterial) adj pressur$).ti,ab,ot. 4 (blood pressur$ or bloodpressur$).ti,ab,ot. 5 or/1‐4 6 (weigh$ or overweight or bodyweight or obes$ or adipos$ or antiobes$ or antiadipos$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 7 (diet$ or nutriti$ or food$ or feed$ or fare or eat$ or nourishment$ or aliment$).ti,ab,ot,hw,kf. 8 exp nutrition therapy/ 9 or/7‐8 10 and/5‐6,9

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Weight‐reducing diet versus no weight‐reducing diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in systolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint | 4 | 731 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.49 [‐7.20, ‐1.78] |

| 2 Change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to endpoint | 6 | 731 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.19 [‐4.83, ‐1.54] |

| 3 Change in body weight from baseline to endpoint | 7 | 880 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.98 [‐4.79, ‐3.17] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cohen 1991.

| Methods | DESIGN: parallel, cluster randomised, no information on blinding DURATION: 12 months NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 1 COUNTRY OF PUBLICATION: USA SPONSOR: ‐ | |

| Participants | WHO PARTICIPATED: hypertensive and obese patients stratified by residents (residents not patients were randomised to intervention or control group)

SETTING: model family practice unit (Pittsburgh) MAIN INCLUSION CRITERIA: age 20 to 75 years; BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (men); ≥ 27 kg/m2 (women); SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg, DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg in 2 or more readings MAIN EXCLUSION CRITERIA: not described in detail NUMBER (educationally oriented intervention vs standard consultation): 15 vs 15 patients were randomised (10 vs 8 physicians); 15 vs 15 were analysed GENERAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): MEAN AGE [YEARS]: 59 vs 60 GENDER [% MALE]: 27 vs 27 NATIONALITY: ‐ ETHNICITY: ‐ WEIGHT [kg]: 92 vs 92 BODY MASS INDEX [kg/m2]: 34 vs 34 SITTING SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ SITTING DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ MEAN ARTERIAL BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 106 vs 106 COMORBID CONDITIONS: obesity ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT: (number of medications 1.6 vs 1.2) DURATION OF HYPERTENSION: ‐ SUBGROUP ANALYSES: weight losers vs weight gainer |

|

| Interventions | LENGTH OF FOLLOW‐UP: 12 months DIETARY INTERVENTION: physicians (n = 10) were taught by a behavioural psychologist; the goal of the dietary advice was to reduce the caloric content of the diet without radically changing the patient's lifestyle; monthly patient consultations and reviewing diet history sheet; the suggested diets were not specifically intended to be salt reducing NO DIETARY INTERVENTION: physicians (n = 8) received no special instructions or materials; the patients continued to be treated with their usual care |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOMES: 1. MORTALITY: ‐ 2. CARDIOVASCULAR MORBIDITY: ‐ 3. ADVERSE EVENTS: ‐ SECONDARY OUTCOMES: 1. CHANGES IN SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ 2. CHANGES IN DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ 3. BODY WEIGHT [kg]: Definition: body weight change from baseline to 6 months, from baseline to 12 months, and from 6 months to 12 months ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES MEASURED IN THE STUDY: 1. Mean arterial blood pressure change in mm Hg 2. Change in number of antihypertensive medications 3. Number of visits |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No details on generation sequence are provided Quote: "The residents were stratified by residency year and randomly assigned to either control or experimental groups. ... The experimental or control status of a patient was determined by the status of the physician, and great care was taken to avoid contamination." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Method of concealment is not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comments: No description of randomisation; since the physicians assigned to the experimental group were taught about the weight‐reducing programme, knowledge of the allocation intervention was not prevented during study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | WITHDRAWALS: none REASONS/DESCRIPTIONS: ‐ |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No primary and secondary outcomes were defined |

| Other bias | High risk | Comments: 1. Lack of information of randomisation 2. Stratified randomisation of investigators instead of patients with very small cluster size |

Croft 1986.

| Methods | DESIGN: parallel, randomised, no information on blinding DURATION: 6 months NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 1 COUNTRY OF PUBLICATION: UK SPONSOR: West Midlands Regional Research Committee; UK | |

| Participants | WHO PARTICIPATED: newly diagnosed hypertensive and obese patients

SETTING: outpatient clinic (1 urban group practice) MAIN INCLUSION CRITERIA: age between 35 and 60 years; BMI > 25 kg/m2; SBP > 140 mm Hg or DBP > 90 mm Hg, or both, in 3 measurements MAIN EXCLUSION CRITERIA: SBP > 200 mm Hg; DBP > 114 mm Hg; previous antihypertensive medication; myocardial infarction or stroke within the previous 3 months; concurrent serious disease, conditions requiring diets, or medication likely to influence weight or blood pressure NUMBER: 66 vs 64 were randomised, 66 vs 64 (last observation carried forward analysis)/47 vs 50 were analysed per protocol (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention) GENERAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): AGE [YEARS]: range 35 to 60 GENDER [% MALE]: 44 vs 61 NATIONALITY: ‐ ETHNICITY: ‐ WEIGHT [kg]: 87 vs 82 BODY MASS INDEX [kg/m2]: ‐ SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 161 vs 161 DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 98 vs 96 COMORBID CONDITIONS: obesity ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT: ‐ DURATION OF HYPERTENSION: newly diagnosed patients SUBGROUP ANALYSES: ‐ |

|

| Interventions | LENGTH OF FOLLOW‐UP: 6 months DIETARY INTERVENTION: active dietary advice for weight reduction by 2 experienced dietitians emphasising the importance of weight reduction for blood pressure control NO DIETARY INTERVENTION: visits at general practitioners, no active dietary advice; if participants indicated that they intended to lose weight, they were not discouraged but were given no specific advice or diet sheets ADDITIONAL TREATMENT: advice about modest restriction of salt use and reduction of excessive alcohol intake |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOMES:

1. MORTALITY: ‐

2. CARDIOVASCULAR MORBIDITY: ‐

3. ADVERSE EVENTS: ‐ SECONDARY OUTCOMES: 1. CHANGES IN SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: Definition: SBP change from baseline to endpoint visit 2. CHANGES IN DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: Definition: DBP change from baseline to endpoint visit 3. BODY WEIGHT [kg]: Definition: body weight change from baseline to endpoint visit ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES MEASURED IN THE STUDY: 1. Start of antihypertensive medication |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No details on generation sequence are provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Method of concealment is not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "... (using random number tables) ..." Comment: as described for normotensive participants only; no information on blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "... The data was submitted to an 'intention to treat' analysis which included all entrants and assumed that no further change in weight or blood pressure occurred for drop‐outs after the last occasion on which they attended."

In addition an "outcome of continued attendance" analysis was used, which compared only those participants still attending after 6 months WITHDRAWALS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): 17 vs 3 REASONS/DESCRIPTIONS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): ‐ |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No primary and secondary outcomes were defined |

| Other bias | High risk | Comments: 1. Lack of information on randomisation and concealment of allocation increases risk of bias even using the LOCF analysis 2. There was no information on reasons for and description of dropouts |

DISH 1985.

| Methods | DESIGN: parallel, randomised, open DURATION: 13 months (56 weeks) NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 4 COUNTRY OF PUBLICATION: USA SPONSOR: grant from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; drugs were supplied by the following companies: Ayerst Laboratories, New York; Merck Sharp & Dohme, West Point, PA; Ciba‐Geigy Corp, Summit, NJ; Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd., Ridgefield, CT; USV Pharmaceutical Corp, Tuckahoe, NY; G.D. Searle & Co, Chicago | |

| Participants | WHO PARTICIPATED: people who were previously enrolled in the HDFP treated with antihypertensive drugs and who had sufficiently controlled hypertension. The dietary change on the return of hypertension after withdrawal of prolonged antihypertensive therapy (DISH) included 7 treatment arms; the results of 2 of those arms met the inclusion criteria for this review (hypertensive and obese patients with either dietary intervention or not)

SETTING: outpatient clinic MAIN INCLUSION CRITERIA: HDFP participants; DBP ≥ 95 mm Hg on first screening, confirmed by second screening with DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg; patients had received antihypertensive medication for at least 5 years; eligible participants had to be "controlled"; hypertensive persons defined by:

MAIN EXCLUSION CRITERIA: history of congestive heart failure; myocardial infarction; stroke or transient ischaemic attacks; creatinine level ≥ 2.5 mg/dl; ß‐blocker therapy for angina; glucocorticoid therapy for indefinite period NUMBER (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): 87 vs 89 participants were randomised GENERAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): MEAN AGE [YEARS]: 56 vs 57 GENDER [% MALE]: 32 vs 36 NATIONALITY: USA ETHNICITY: black: 62% to 70%, no further information WEIGHT [kg]: 86 vs 90 BODY MASS INDEX [kg/m2]: ‐ SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 127.6 vs 127.6 DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 80.9 vs 79.6 COMORBID CONDITIONS: obesity ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT [%]: 100 vs 100 DURATION OF HYPERTENSION: at least 5 years in both groups SUBGROUP ANALYSES: results from participants with mild and severe hypertension (not clear whether subgroups were predefined or post‐hoc) |

|

| Interventions | LENGTH OF FOLLOW‐UP: 13 months (56 weeks ) DIETARY INTERVENTION: according to revised "Metropolitan Life Insurance" standards; intervention consisted of 8 initial weekly group sessions followed by monthly sessions plus individual consultation as needed NO DIETARY INTERVENTION: no recommendations ADDITIONAL TREATMENT: discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment using a step‐down withdrawal program; biweekly consultations for BP measurement for 16 weeks followed by monthly consultations; no change in salt uptake |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOMES:

1. MORTALITY: ‐

2. CARDIOVASCULAR MORBIDITY: ‐

3. ADVERSE EVENTS:

Definition: withdrawal due to the need to restart antihypertensive medication SECONDARY OUTCOMES: 1. CHANGES IN SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ 2. CHANGES IN DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: ‐ 3. BODY WEIGHT [kg]: Definition: body weight change from baseline to endpoint visit ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES MEASURED IN THE STUDY: 1. Number of participants without antihypertensive medication 2. Change in sodium excretion |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No details on generation sequence are provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Method of concealment is not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comment: Open design, no blinding described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | WITHDRAWALS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): 0 vs 0 concerning the endpoint success of withdrawal from antihypertensive medication; 20 vs 12 concerning body weight at week 56; although there were no losses to follow‐up in the relevant subgroups concerning success of discontinuing antihypertensive treatment, for 13% respectively 23% participants weight at week 56 is not reported REASONS/DESCRIPTIONS: No reasons for incomplete data are mentioned |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No primary and secondary outcomes were defined |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: 1. Randomisation before consent of participants (possible selection bias) 2. Different body weight at baseline 3. Participants participated in previous trial for 5 years (selected population may not be representative) |

Jalkanen 1991.

| Methods | DESIGN: parallel, randomised, no information on blinding DURATION: 12 months NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: 2 COUNTRY OF PUBLICATION: ‐ SPONSOR: ‐ | |

| Participants | WHO PARTICIPATED: overweight hypertensive patients (selected from files)

SETTING: outpatient clinic (2 hypertension clinics in Finland) MAIN INCLUSION CRITERIA: age 35 to 59 years; BMI 27 to 34 kg/m2; DBP ≥ 95 mm Hg MAIN EXCLUSION CRITERIA: ‐ NUMBER: 25 vs 25 were randomised; 24 vs 25 were analysed (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention) GENERAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): MEAN AGE [YEARS]: 49 GENDER [% MALE]: ‐ (" ... as many men as women ... ") NATIONALITY: ‐ ETHNICITY: ‐ WEIGHT [kg]: 86 vs 80 BODY MASS INDEX [kg/m2]: ‐ SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 152 vs 155 DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: 101 vs 102 COMORBID CONDITIONS: ‐ ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT: ‐ (25 of 50 enrolled participants antihypertensive treatment with diuretics or ß‐blocker) DURATION OF HYPERTENSION: ‐ SUBGROUP ANALYSES: ‐ |

|

| Interventions | LENGTH OF FOLLOW‐UP: 12 months DIETARY INTERVENTION: individually planned energy‐restricted diet of 1000 to 1500 kcal per day, weekly (after 6 months every 3 weeks); sessions including discussions and lessons on behavioural modification, choice of food, physical exercise, and medical aspects of overweight and weight reduction; 1.5 hour duration; total number of lectures about 40 hours; the participants received leaflets on the reduction of salt and fat consumption and on the increase of physical activity; lectures by different medical experts; nutritionists interview; laboratory tests NO DIETARY INTERVENTION: visits every 3 months; no personal counselling; nutritionists interview; laboratory tests ADDITIONAL TREATMENT: participants' doctors were asked to keep the dosage of antihypertensive drugs at the initial level |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOMES:

1. MORTALITY: ‐

2. CARDIOVASCULAR MORBIDITY: ‐

3. ADVERSE EVENTS: ‐ SECONDARY OUTCOMES: 1. CHANGES IN SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: Definition: SBP change from baseline to endpoint visit 2. CHANGES IN DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE [mm Hg]: Definition: DBP change from baseline to endpoint visit 3. BODY WEIGHT [kg]: Definition: body weight change from baseline to endpoint visit ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES MEASURED IN THE STUDY: 1. Change in lipid parameters 2. Change in potassium and sodium excretions 3. Change in dietary factors (fats and protein) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No details on generation sequence are provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Method of concealment is not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comments: No description of randomisation; no information on blinding for investigators |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | WITHDRAWALS (dietary intervention vs no dietary intervention): 1 vs 0 REASONS/DESCRIPTIONS: ‐ |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No primary and secondary outcomes were defined |

| Other bias | High risk | Comments: 1. Lack of information on randomisation and concealment of allocation and blinding increases risk of bias 2. No information provided on the reason for and description of the dropout in the intervention group 3. The effect of weight reduction is not clearly identified; advice about behavioural modification, physical exercise, and salt reduction were also part of the intervention |

ODES 1995.

| Methods | DESIGN: parallel, 2x2 factorial, randomised, open design DURATION: 12 months NUMBER OF STUDY CENTRES: unclear (probably 1, because all eligible participants were screened at the Ullevaal Hospital, Oslo) COUNTRY OF PUBLICATION: Norway SPONSOR: supported by grant from the Research Council of Norway, the Norwegian Council of Cardiovascular Diseases, and the insurance company Vital Friskvern | |

| Participants | WHO PARTICIPATED: men and women ≥ 40 years old from screening programme for cardiovascular risk factors in Oslo (Norway) since 1981;

participants were post‐hoc divided in tertiles according to DBP (tertile 1 DBP > 91 mm Hg, tertile 2 DBP 84 to 91 mm Hg, tertile 3 DBP < 84 mm Hg); only subgroups of tertile 1 (DBP > 91 mm Hg) will be reported here