Abstract

We report the first FeII‐catalyzed biomimetic aerobic oxidation of alcohols. The principle of this oxidation, which involves several electron‐transfer steps, is reminiscent of biological oxidation in the respiratory chain. The electron transfer from the alcohol to molecular oxygen occurs with the aid of three coupled catalytic redox systems, leading to a low‐energy pathway. An iron transfer‐hydrogenation complex was utilized as a substrate‐selective dehydrogenation catalyst, along with an electron‐rich quinone and an oxygen‐activating Co(salen)‐type complex as electron‐transfer mediators. Various primary and secondary alcohols were oxidized in air to the corresponding aldehydes or ketones with this method in good to excellent yields.

Keywords: aerobic oxidation, biomimetic reactions, electron transfer, homogeneous catalysis, iron

Round round get around: An FeII‐catalyzed biomimetic aerobic oxidation of alcohols was developed based on the biological oxidation of alcohols in the respiratory chain. Electron transfer from the alcohol to molecular oxygen occurs via three coupled catalytic redox cycles, leading to a low‐energy pathway. An Fe complex was utilized as a substrate‐selective catalyst, along with a quinone and an oxygen‐activating Co complex as electron‐transfer mediators.

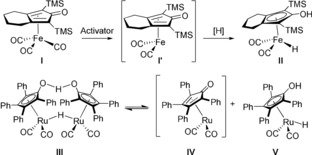

Oxidations constitute a fundamental class of reactions in organic chemistry, and many important chemical transformations involve oxidation steps. Although a large number of oxidation reactions have been developed, there is an increasing demand for more selective, mild, efficient, and scalable oxidation methods.1 Of particular interest are methods inspired by biological pathways,2 in which oxidants such as molecular oxygen (O2) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are employed. These oxidants are ideal to use in industrial oxidations because they are inexpensive and environmentally friendly. However, the direct oxidation of an organic substrate by H2O2 or O2 is challenging owing to the large energy barrier and low selectivity associated with such reactions. The use of a substrate‐selective redox catalyst (SSRC) in combination with direct re‐oxidation of the reduced form of the SSRC (i.e., SSRCred) by H2O2 or O2 is also often associated with a high energy barrier. Nature's elegant way of circumventing this problem is through the orchestration of a variety of enzymes and co‐enzymes that can act as electron‐transfer mediators (ETMs), which lower the overall barrier for electron transfer from SSRCred to H2O2 or O2 (Scheme 1). These ETMs are part of what is called the electron transport chain (ETC), where O2 is typically used as the terminal oxidant.3 This bypasses the high kinetic barrier associated with direct oxidation by O2 and leads to a lower overall energy barrier through stepwise electron transfer.

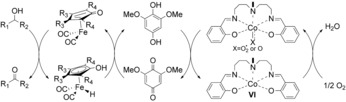

Scheme 1.

Principle for oxidation with O2 or H2O2 through the use of ETMs. ETM=electron transfer mediator, SSRC=substrate selective redox catalyst.

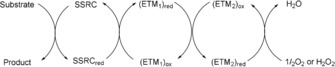

Iron catalysis has gained significant attention in the past few years and has found applications in many different transformations, including cross‐coupling reactions and transfer‐hydrogenation reactions.4, 5, 6 (Cyclopentadienone)iron tricarbonyl complexes, first synthesized by Reppe and Vetter in 1953,7 constitute a prominent class of catalysts for hydrogen‐transfer reactions, and the first catalytic reaction with these types of complexes was reported by the group of Casey in 2007.8 One of these complexes is I, which can be activated in situ to generate dicarbonyl intermediate I′, which can in turn be reduced to iron hydride II (Scheme 2). The activation of I can be done in different ways, one of which being oxidative decarbonylation by trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMANO).9 Iron hydride II was first isolated by the group of Knölker.10, 11, 12 Complex I and related iron tricarbonyl complexes have found extensive use in transfer‐hydrogenation reactions,8, 13 and our group has applied I in both the dynamic kinetic resolution of sec‐alcohols14 and the cycloisomerization of α‐functionalized allenes.15

Scheme 2.

Activation of iron tricarbonyl complex (I) and Shvo's catalyst (III).

The cyclopentadienone(iron) and cyclopentadienyl(iron) catalysts (I, I′, and II) are related to the Shvo catalyst III and its monomers IV and V (Scheme 2). In fact, I′ and II are isoelectronic to IV and V, respectively. Intermediates I′ and IV are proposed to be the active dehydrogenation catalysts in the racemization of alcohols.14, 16 We therefore envisioned that cyclopentadienone(iron) complex A could be used as an efficient dehydrogenation catalyst for alcohols and that the cyclopentadienyl(iron) hydride B could be recycled to A through oxidation by a benzoquinone (Scheme 3). Reoxidation of the hydroquinone could be achieved by using a combined system consisting of O2 and an oxygen‐activating metal macrocycle (e.g., VI) to give biomimetic aerobic oxidation of the alcohol. The biomimetic approach depicted in Scheme 3 was previously successfully applied by our group using the Shvo catalyst III.17 Related biomimetic oxidations through similar electron‐transfer chains have also been reported by our group using palladium18 or osmium19 as substrate‐selective redox catalysts.20

Scheme 3.

The biomimetic oxidation approach using an iron catalyst as SSRC.

Other groups have reported the use of FeIII porphyrin complexes in biomimetic oxidation of alcohols.21 However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no examples on the use of FeII complexes in biomimetic aerobic oxidation of alcohols.

Our initial attempts began by investigating various 1,4‐benzoquinones as stoichiometric oxidants in the iron‐catalyzed oxidation of 1‐phenylethanol (1 a) using I as catalyst. Of the quinones tested, 2,6‐dimethoxy‐1,4‐benzoquinone (DMBQ) was found to be the best, giving acetophenone (2 a) in a yield of 9 % after 60 min (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information).

We next studied the oxidation using DMBQ as the stoichiometric oxidant. Since the oxidation of the alcohol can be done at a lower oxidation potential if the alcohol is more electron‐rich, the substrate was changed to 1‐(p‐methoxyphenyl)ethanol (1 b). The catalyst loading of I was also increased to 10 mol %. Under these reaction conditions, a yield of 26 % of 2 b was obtained after 60 min (Table 1, entry 1). With the ultimate goal of developing an aerobic oxidation reaction, it was of interest to determine the sensitivity of the system towards O2. We therefore studied the oxidation with DMBQ (1.2 equiv) under air as well as under pure O2, with and without cobalt complex VI (for the structure of VI, see Scheme 3). In both cases (O2 or air), the expected oxidative deactivation of the catalyst was observed (entries 2,3). Next, several solvents were screened (entries 4–7) in the presence of air, with anisole giving the best result (entry 7). To demonstrate the necessity of iron catalyst I for the reaction, a blank reaction without I was performed, which as expected gave negligible yield of ketone product 2 b (entry 8).

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions using DMBQ as oxidant.

|

Entry[a] |

Solvent |

Additive |

Atmosphere |

GC yield 10 min [%][b] |

GC yield 30 min [%][b] |

GC yield 60 min [%][b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Toluene |

– |

Ar |

15 |

21 |

26 |

|

2 |

Toluene |

– |

O2 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

|

3 |

Toluene |

VI [c] |

Air |

9 |

12 |

14 |

|

4 |

CPME |

VI [c] |

Air |

11 |

11 |

11 |

|

5[d] |

THF |

VI [c] |

Air |

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

6[d] |

2‐Me THF |

VI [c] |

Air |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

7 |

Anisole |

VI [c] |

Air |

40 |

44 |

47 |

|

8[e] |

Anisole |

VI [c] |

Air |

3 |

3 |

3 |

[a] General reaction conditions: The reaction was conducted at 100 °C with 0.5 mmol of 1 b, 0.6 mmol of DMBQ, 0.24 mmol of VI, 0.05 mmol of I, 0.05 mmol of TMANO, and 3 mL of solvent. [b] Yields were determined by GC analysis. [c] 40 mol % of VI. [d] Run at 70 °C. [e] Blank reaction without I.

We next studied the use of cyclopentadienone(iron) catalyst VII, which was previously reported by the group of Funk to be more active than I in both the oxidation of alcohols and in the reduction of ketones and aldehydes (Figure 1).13a Changing the catalyst from I to VII led to a significant improvement of the oxidation of 1 b by DMBQ (1.2 equiv) under air, most likely due to the increased stability of complex VII in the presence of air (Table 2, entry 1).

Figure 1.

Iron tricarbonyl complex VII (DMPh=3,5‐dimethylphenyl).

Table 2.

Optimization of the amounts of VI, VII, and DMBQ.

|

Entry[a] |

VII [mol %] |

VI [mol %] |

DMBQ [mol %] |

GC yield 10 min [%][b] |

GC yield 60 min [%][b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

10 |

40 |

120 |

81 |

81 |

|

2 |

10 |

2 |

20 |

50 |

54 |

|

3 |

10 |

2 |

40 |

67 |

74 |

|

4 |

20 |

2 |

20 |

65 |

76 |

|

5 |

20 |

4 |

40 |

70 |

80 |

|

6 |

10 |

4 |

40 |

68 |

75 |

|

7[c] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

18 |

41 |

|

8[d] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

59 |

69 |

|

9[e] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

58 |

64 |

|

10[f] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

67 |

71 |

|

11[g] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

81 |

>95 |

|

12[g,h] |

10 |

4 |

40 |

80 |

>95 |

[a] General reaction conditions: The reaction was conducted under air at 100 °C with 0.5 mmol of 1 b, and 3 mL of anisole. [b] Yields were determined by GC analysis. [c] 80 °C. [d] 2 % O2 atmosphere. [e] Addition of 2 equiv of water. [f] Addition of 4 Å molecular sieves. [g] Higher concentration (0.33 m of 1 b, 1.5 mL of anisole). [h] Addition of 1 equiv of K2CO3.

At this point, we set out to make the reaction catalytic with respect to VI, VII, and DMBQ. When the amounts of DMBQ and cobalt complex VI were reduced to the amounts used in our previous work on ruthenium‐catalyzed oxidation of alcohols,17a the conversion dropped significantly (Table 2, entry 2). Doubling the amounts of either VII or DMBQ led to an increase in yield to 74–76 % (entries 3–4). However, when both VII and DMBQ were increased, only a marginal further increase was observed (entry 5). Varying the amount of VI was found not to affect the reaction rate significantly (cf. entries 3 and 6). Reducing the temperature to 80 °C significantly lowered the yield of ketone 2 b (entry 7), and reducing the O2 amount to 2 % did not significantly affect the yield (entry 8). To examine the effect of water on the reaction, 2 equiv of water were added to the reaction mixture, which led to a decrease in yield from 75 to 64 %. (cf. entries 6 and 9). The addition of 4 Å molecular sieves to the reaction mixture did not lead to any observed improvement and in fact proved slightly detrimental (entry 10). Increasing the concentration two‐fold (from 0.17 m to 0.33 m) led to essentially full conversion after 1 h (entry 11). The addition of 1 equiv of K2CO3 was found not to affect the yield, but led to a more robust and easily reproducible procedure (entry 12).

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we turned our attention to the substrate scope, starting with substitutions on the aromatic ring. Benzylic sec‐alcohols with neutral or electron‐donating groups on the aromatic ring performed very well and gave the corresponding ketones in high yields (Scheme 4, 2 a–2 c). Electron‐withdrawing groups, however, gave slightly lower yields in the range of 60–80 % and required a higher catalyst loading (2 d–2 f). These results can be explained by the fact that electron‐deficient benzylic alcohols are not as easily oxidized as their electron‐rich counterparts. With the lower reaction rate of the electron‐deficient alcohols, competing deactivation of the catalyst by O2 becomes more severe and, as a result, a lower yield is obtained. Interestingly, the nitrile‐substituted ketone 2 f could be isolated in a yield of 60 % even though the nitrile group typically acts as a strong coordinating ligand to iron. The use of 1‐phenylpropanol (1 g) afforded ketone 2 g in 70 % yield of isolated product. Alkyl‐substituted alcohols could also be oxidized and 2 i was isolated in 80 % yield.

Scheme 4.

Substrate scope. General reaction conditions: The reaction was conducted under air at 100 °C with 0.5 mmol of 1, 0.05 mmol of VII, 0.05 mmol of TMANO, 0.2 mmol DMBQ, 0.02 mmol of VI, 0.5 mmol of K2CO3, and 1.5 mL of anisole. [a] Yield of isolated product. [b] NMR yield determined by using 1,3,5‐trimethoxybenzene as internal standard. [c] 0.1 mmol (20 mol %) of VII used.

Primary alcohols also worked well and could be oxidized to their corresponding aldehydes 2 j–2 m. With benzylic primary alcohols, good to excellent yields of aldehydes 2 j–2 l were obtained. However, cyclohexylmethanol gave a moderate yield of aldehyde 2 m. The ability of iron catalyst VII to promote the oxidation of primary alcohols is in contrast to our previous work on the corresponding biomimetic aerobic ruthenium‐catalyzed oxidation of alcohols using the Shvo catalyst. In our previous work, aldehydes could not be obtained from primary alcohols due to disproportionation of the aldehydes caused by the Shvo catalyst.17a

In conclusion, we have developed the first example of an iron(II)‐catalyzed biomimetic aerobic oxidation of alcohols, where electron‐transfer mediators are used to lower the energy barrier for the electron transfer from substrate to molecular oxygen. The electron‐transfer system used is reminiscent of the respiratory chain. Through the use of this biologically inspired method, various aldehydes and ketones could be efficiently prepared from their corresponding primary or secondary alcohols in good to excellent yields.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (2016‐03897), the Olle Engkvist Foundation, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW 2016.0072) is gratefully acknowledged.

A. Guðmundsson, K. E. Schlipköter, J.-E. Bäckvall, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5403.

References

- 1. Modern Oxidation Methods, 2 nd ed. (Ed.: J.-E. Bäckvall), Wiley-VCH, Weinham, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Piera J., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3506–3523; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 3558–3576; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Murahashi S.-I., Zhang D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1490–1501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Chen B., Wang L., Gao S., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5851–5876. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin D. R., Mayushov D. V., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross-coupling reactions:

- 4a. Nakamura M., Matsuo K., Ito S., Nakamura E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3686–3687; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Cahiez G., Moyeux A., Buendia J., Duplais C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13788–13789; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Fürstner A., De Souza D., Parra-Rapado L., Jensen J. T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5358–5360; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2003, 115, 5516–5518; [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Kessler S. N., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3734–3738; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 3798–3802; [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Kessler S. N., Hundemer F., Bäckvall J.-E., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7448–7451; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Piontek A., Bisz E., Szostak M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11116–11128; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 11284–11297; [Google Scholar]

- 4g. Parchomyk T., Koszinowski K., Synthesis 2017, 49, 3269–3280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Transfer-hydrogenation reactions:

- 5a. Shaikh N. S., Enthaler S., Junge K., Beller M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2497–2501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 2531–2535; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Langlotz B. K., Wadepohl H., Gade L. H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4670–4674; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 4748–4752; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Sui-Seng C., Freutel F., Lough A. J., Morris R. H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 940–943; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 954–957; [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Zuo W., Lough A. J., Li Y. F., Morris R. H., Science 2013, 342, 1080–1083; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Farrar-Tobar R. A., Wozniak B., Savini A., Hinze S., Tin S., de Vries J. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1129–1133; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 1141–1145; [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Espinal-Viguri M., Neale S. E., Coles N. T., Macgregor S. A., Webster R. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 572–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Books and reviews: “Iron Catalysis: Historic Overview and Current Trends”:

- 6a. Bauer E. B. in Topics in Organometallic Chemistry: Iron Catalysis II (Ed.: E. B. Bauer), Springer International, Cham, 2015, pp. 1–18; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Bauer I., Knölker H.-J., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3170–3387; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Bolm C., Legros J., Le Paih J., Zani L., Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6217–6254; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Sherry B. D., Fürstner A., Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1500–1511; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Wei D., Darcel C., Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2550–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reppe W., Vetter H., Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1953, 582, 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Casey C. P., Guan H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5816–5817; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Casey C. P., Guan H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2499–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knölker H.-J., Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2941–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Knölker H.-J., Heber J., Mahler C. H., Synlett 1992, 1002–1004; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Knölker H.-J., Heber J., Synlett 1993, 924–926. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knölker H.-J., Goesmann H., Klauss R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2064–2066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1999, 111, 2196–2199. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reviews on Knölker-type iron catalysts and non-innocent ligands:

- 12a. Quintard A., Rodriguez J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4044–4055; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 4124–4136; [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Khusnutdinova R., Milstein D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12236–12273; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 12406–12445. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Funk T. W., Mahoney A. R., Sponenburg R. A., Kathryn P. Z., Kim D. K., Harrison E. E., Organometallics 2018, 37, 1133–1140; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Roudier M., Constantieux T., Quintard A., Chimia 2016, 70, 97–101; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Brown T. J., Cumbes M., Diorazio L. J., Clarkson G. J., Wills M., J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 10489–10503; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Yan T., Feringa B. L., Barta K., Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5602; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13e. Facchini S. V., Cettolin M., Bai X., Casamassima G., Pignataro L., Gennari C., Piarulli U., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1054–1059; [Google Scholar]

- 13f. Polidano K., Allen B. D. W., Williams J. M. J., Morill L. C., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6440–6445. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Gustafson K., Guðmundsson A., Lewis K., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 1048–1051; For related work on the DKR of sec-alcohols see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. El-Sepelgy O., Alandini N., Rueping M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13602–13605; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 13800–13803; [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Yang Q., Zhang N., Liu M., Zhou S., Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 2487–2489. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a.see Ref. [14a];

- 15b. Guðmundsson A., Gustafson K. P. J., Mai B. K., Yang B., Himo F., Bäckvall J.-E., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 12–16; [Google Scholar]

- 15c. Guðmundsson A., Gustafson K. P. J., Mai B. K., Hobiger V., Himo F., Bäckvall J.-E., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1733–1737. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Warner M. C., Casey C. P., Bäckvall J.-E., Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 37, 85–125; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Warner M. C., Bäckvall J.-E., Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2545–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Csjernyik G., Éll A. H., Fadini L., Pugin B., Bäckvall J.-E., J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 1657–1662; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Samec J. S. M., Éll A. H., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2005, 11, 2327–2334; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Babu B. P., Endo Y., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11524–11527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Bäckvall J.-E., Awasthi A. K., Renko Z. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 4750–4752; [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Bäckvall J.-E., Hopkins R. B., Grennberg H., Mader M., Awasthi A. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 5160–5166; [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Gigant N., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 10799–10803; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Babu B. P., Meng X., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4140–4145; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18e. Volla C. M. R., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 14209–14213; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 14459–14463; [Google Scholar]

- 18f. Liu J., Ricke A., Yang B., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16842–16846; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 17084–17088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Jonsson S. Y., Färnegårdh K., Bäckvall J.-E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1365–1371; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Closson A., Johansson M., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Commun. 2004, 1494–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recent work by others on related biomimetic electron transfer systems: Pd-catalysis:

- 20a. Morandi B., Wickens Z. K., Grubbs R. H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2944–2948; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 3016–3020; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Pattillo C. C., Strambeanu I. I., Calleja P., Vermeulen N. A., Mizuno T., White M. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1265–1272; Organocatalysis: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Ta L., Axelsson A., Sunden H., Green Chem. 2016, 18, 686–690. [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Chauhan S. M. S., Kandadai A. S., Jain N., Kumar A., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 1345–1347; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Han J. H., Yoo S.-K., Seo J. S., Hong S. J., Kim S. K., Kim C., Dalton Trans. 2005, 402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary