Abstract

This study assesses the availability of statistical code from research articles using Medicare data published in leading general medical journals.

Limited access to statistical code (ie, computer programming instructions used to perform analyses from research data) following publication of an article may be a barrier to open science, methodologic rigor, and the reproducibility of research.1,2 Unlike clinical research data that may raise privacy concerns, sharing statistical code should be straightforward.3 We assessed the availability of statistical code from research articles published in leading general medical journals, focusing on studies using Medicare data.4

Methods

We searched for all studies that cited use of national Medicare data sets (Part A and/or B) published in 6 general medical journals between January 2017 and December 2018 (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). We sent an email outlining our project to the corresponding authors of identified articles (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement) up to 3 times over 6 weeks at 2-week intervals. We requested statistical code; when code was available, one of us (J.L.) assessed if it was complete or partial, consulting with a second author (B.K.N.) when needed. We defined code as complete if it could fully reproduce the study from cohort construction to final results. We also asked the corresponding authors to complete an anonymous survey (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board exempted the study from human subjects review and waived consent.

Results

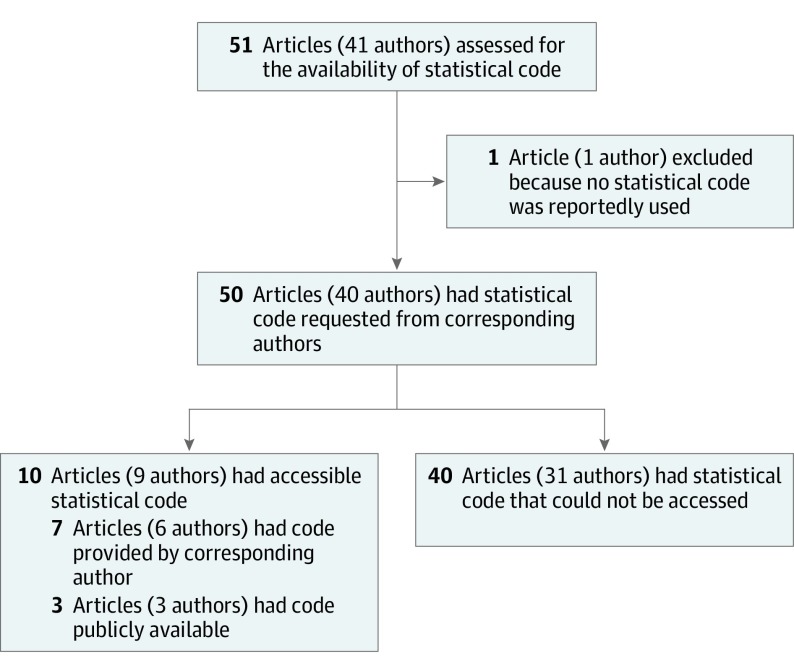

We identified 51 articles with 41 unique corresponding authors (Figure). One article reported no use of statistical code. From the remaining 50 articles, we were able to obtain code from 10; for 3, statistical code was publicly available online, and for 7, the corresponding authors provided it (Table). For the 8 articles that stated in the publication that code was available on request, code was only provided for 3. Of the 41 corresponding authors contacted, 22 did not respond; of the 19 who responded, 16 completed the survey. Primary concerns included code was not clean enough to share (n = 2), uncertainty as to how code would be used (n = 3), and time and effort involved in sharing code (n = 3). When asked if they would support an online public repository of code, 12 of 16 authors who completed the survey indicated support.

Figure. Flowchart of Articles and Authors From Which Statistical Code Was Accessible and Not Accessible.

Table. Features of Articles Using National Medicare Data Sets Published in 6 General Medical Journals Between January 2017 and December 2018.

| Feature | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total articles, No. | 51 (100) |

| Statistical code accessed | 10 (20) |

| Online | 3 (6) |

| Complete | 1 (2) |

| Partial | 2 (4) |

| Provided by corresponding author | 7 (14) |

| Complete | 6 (12) |

| Partial | 1 (2) |

| Statistical code not accessed | 41 (80) |

| No statistical code reportedly used | 1 (2) |

| Email undeliverable | 1 (2) |

| No response to delivered emails | 30 (59) |

| Responded but unable to share code | 9 (18) |

| Responded but analyst had left | 1 (2) |

| Responded but failed to follow up | 3 (6) |

| Responded but delays required owing to sponsor permission | 4 (8) |

| Responded but lacked authority and referred to sponsor | 1 (2) |

| Journal | |

| Annals of Internal Medicine | 9 (18) |

| The BMJ | 10 (20) |

| JAMA | 8 (16) |

| JAMA Internal Medicine | 20 (39) |

| Lancet | 0 |

| New England Journal of Medicine | 4 (8) |

Discussion

Our study found limited availability of statistical code for research articles using Medicare data in general medical journals. Several explanations are possible. Our request may have been perceived as vague or not serious, leading some corresponding authors to be deterred because of the effort required to prepare statistical code for distribution. Others may have been hesitant to share code because of concerns about the intent of our study or to protect intellectual property. In another case (that involved multiple articles), a corresponding author reported possible barriers owing to requirements for sponsor permission. Finally, some email accounts may have become inactive or blocked, leading to some nonresponses. As our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of a simple approach for accessing statistical code, we did not contact coauthors when we received no response from the corresponding author, nor did we use informal contact channels.

The limitations of our study notwithstanding, these findings indicate that the restricted availability of statistical code after publication of research articles using Medicare data can be a barrier to the reproducibility of research. Our findings also suggest that the traditional custom of contacting corresponding authors after publication may be insufficient for obtaining statistical code. One solution would be that medical journals encourage or require submission of statistical code before an article is published. This approach would be similar to that in other fields, such as in the basic sciences5 or economics (eg, where statistical code for Medicare studies is posted on the American Economic Association website6). Journals could also build on data sharing policies for clinical trials endorsed by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, under which authors are required to state in the article whether individual data will be shared, what will be shared, and by what access criteria, including the mechanism.

eAppendix 1. Articles included in the analysis that used national Medicare datasets and were published in 6 general medical journals between 2017 and 2018.

eAppendix 2. Email template.

eAppendix 3. Survey.

References

- 1.Brown AW, Kaiser KA, Allison DB. Issues with data and analyses: errors, underlying themes, and potential solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(11):2563-2570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708279115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM, Ross JS, Gross CP, et al. A historic moment for open science: the Yale University Open Data Access Project and Medtronic. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):910-911. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-12-201306180-00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nallamothu BK. Trust, but verify. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(7):e005942. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mues KE, Liede A, Liu J, et al. Use of the Medicare database in epidemiologic and health services research: a valuable source of real-world evidence on the older and disabled populations in the US. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:267-277. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S105613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nature Research . Reporting standards and availability of data, materials, code and protocols. Accessed January 28, 2020. https://www.nature.com/nature-research/editorial-policies/reporting-standards

- 6.American Economic Association . Data and code availability policy. Accessed November 4, 2019. https://www.aeaweb.org/journals/policies/data-code

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Articles included in the analysis that used national Medicare datasets and were published in 6 general medical journals between 2017 and 2018.

eAppendix 2. Email template.

eAppendix 3. Survey.