Key Points

Question

Is either nurse-led telephone or short message service support effective in improving infant feeding practices and tummy time and reducing screen time?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial found that telephone support increased rates of appropriate timing of introducing solid foods, early-start tummy time, and cup use, while telephone and short message service support increased rates of having no screen time and having no bottle at bedtime.

Meaning

Both telephone and short message service interventions can be effective in reducing screen time, preventing a bottle at bedtime, and improving some infant feeding practices and tummy time.

Abstract

Importance

There is limited information as to whether telephone or short message service (SMS) support is effective in improving infant feeding practices and tummy time and reducing screen time.

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of either nurse-led telephone or SMS support in improving infant feeding practices and tummy time and reducing screen time.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was part of a 2-year, 3-group parallel, randomized clinical trial conducted from February 23, 2017, to November 30, 2018, among 1155 women in the third trimester of pregnancy in New South Wales, Australia. It reports the main outcomes at 6 and 12 months of child age. All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat principle.

Interventions

The intervention consisted of staged information booklets mailed to the intervention groups, each followed by either a nurse-led telephone support session or SMS intervention, antenatally and at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 months after birth.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were infant feeding practices at both 6 and 12 months and tummy time at 6 months. The secondary outcome was screen time at 12 months.

Results

Of 1155 mothers, 947 (82%; mean [SD] age, 32.5 [5.0] years) completed follow-up surveys at 6 months; 920 mothers (80%) completed follow-up surveys at 12 months. Compared with the control group, telephone support led to higher odds of appropriate timing of introducing solid foods (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.68 [95% CI, 1.22-2.32]), cup use (AOR, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.12-2.13]), and early-start tummy time (AOR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.18-2.25]) at 6 months and higher odds of having no screen time (AOR, 1.80 [95% CI, 1.28-2.53]) and no bottle at bedtime (AOR, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.23-2.42]) at 12 months. Use of SMS also led to higher odds than the control group of having no screen time (AOR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.08-1.52]) and having no bottle at bedtime (AOR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.10-1.51]) at 12 months. No significant differences were found in breastfeeding rates between the telephone support, SMS support, and control groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Both the nurse-led telephone support and SMS interventions were effective in reducing screen time and bottle use at bedtime. Telephone support was also effective in promoting the appropriate timing of the introduction of solid foods, early-start tummy time, and cup use.

Trial Registration

http://anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12616001470482

This randomized clinical trial examines the effectiveness of either nurse-led telephone or short message service support in improving infant feeding practices and tummy time and reducing screen time.

Introduction

Promoting healthy infant feeding practices, such as breastfeeding, timing of introduction of solid foods, and cup use, has been recommended as an important strategy to prevent obesity in the early years.1,2 The World Health Organization’s Commission report on Ending Childhood Obesity highlights that the first years of life are critical in establishing good nutrition, physical activity, and reduced screen time behaviors that reduce the risk of developing obesity.3 “Tummy time,” or time awake in the prone position, is a form of early movement or physical activity recommended for infants younger than 6 months.4 Recent research has linked tummy time to early infant motor movement and weight status.5

Research evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) suggests that interventions communicating health information to mothers in the first years of their child’s life improves infant feeding practices and tummy time. For example, the Healthy Beginnings Trial (HBT) delivered through staged home visits by community nurses led to longer duration of breastfeeding, appropriate timing of introduction of solid foods, and earlier daily practice of tummy time.6 Other early intervention trials implementing education sessions for groups of mothers also resulted in improved feeding practices.7,8,9 More important, the HBT also shows that improved infant feeding practices reduced the mean body mass index of children at 2 years of age.10 The commonality among these RCTs is the use of face-to-face educational sessions with mothers either at home or in group sessions, which potentially limits the reach of the intervention.

There is emerging evidence that telephone-based counseling interventions and short message service (SMS)–delivered interventions may promote a change in behavior and improve behaviors relevant to obesity prevention and weight management based on a number of meta-analyses and systematic reviews.11,12,13 However, to our knowledge, few RCTs have tested the efficacy of using telephone or SMS support for the purpose of promoting healthy infant feeding practices to reduce the early onset of childhood obesity. To our knowledge, no research trial has reported using telephone or SMS support to prevent infant screen time exposure. Findings from a handful of RCTs that used telephone support14,15,16,17 and SMS support18,19,20 were promising but inconclusive. The lengths of intervention in these studies (predominantly focused on breastfeeding) were relatively short, ranging from 2 weeks to 6 months after birth. To our knowledge, the literature on telephone or SMS support for the appropriate timing of the introduction of solid foods and cup use is scarce.

Thus, a 3-group RCT21 was conducted to determine the effectiveness of nurse-led telephone or SMS support in communicating Healthy Beginnings advice6,10 to mothers for the promotion of healthy infant feeding practices and for the prevention of early-onset childhood obesity. The aim of this particular study was to report on the findings from the trial at 6 and 12 months of child age.

Methods

Study Design

This study was part of a 2-year, 3-group, parallel RCT conducted from February 23, 2017, to November 30, 2018. The trial was approved by the Sydney Local Health District Ethics Review Committee. Participating mothers provided written consent. A detailed description of the methods was published prior to the commencement of the study.21 The trial protocol was implemented without changes (Supplement 1). This study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Setting

The study was conducted in metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The recruitment of study participants took place at the antenatal clinics in 7 hospitals of 4 local health districts.

Participants and Recruitment

Pregnant women were approached for their eligibility by 4 research assistants at the clinics with a letter of invitation and information about the study. Women were eligible to participate if they were aged 16 years or older, between weeks 24 and 34 of pregnancy, able to communicate in English, had a mobile telephone, and lived in the recruitment areas. Once written consent was obtained, women were required to fill in a registration form with their contact information to allow the research assistant to make further arrangements for baseline data collection and study group randomization. The full recruitment process has been reported elsewhere.22

Randomization

A web-based randomization plan was generated using randomly permuted blocks (n = 6) (http://www.randomization.com/). The randomization was stratified by local health districts. The study participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups (ie, telephone support, SMS support, or control group) after they completed a baseline survey.

Intervention

The process of developing the intervention was informed by the Health Belief Model.23 The 6 staged interventions from the third trimester to 12 months of the child’s age were developed based on the HBT,6,10,21 which corresponded to key stages of child feeding and movement, including 1 intervention at the third trimester and 5 interventions postnatally at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 months of age. The staged intervention booklets were developed and mailed to the intervention groups matching the delivery timing of the telephone support and SMS support.

Intervention Group 1 (Telephone Support)

One week after the mailing of the intervention booklet, a child and family health nurse called the participants to provide support. Each call was approximately 30 to 60 minutes long, and the nurse and mother talked about the intervention information provided in the booklets and discussed issues raised by the mother. Guided by the HBT checklists,6 6 telephone support scripts were developed to assist the nurses providing telephone support (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 2).

Intervention Group 2 (SMS Support)

One week after the mailing of the intervention booklet, a set of SMS messages were sent to the participant twice a week for 4 weeks via a 2-way automated SMS system at a predetermined time (10 am to 1 pm). A full list of SMS messages can be found in eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2. These messages were used to reinforce the intervention information and key messages in the booklets.

Control Group

Mothers in the control group received usual care from child and family health nurses in the local health districts. Home safety promotion materials and a newsletter on “Kids’ Safety” were sent to the control group at the third trimester and at 3, 6, and 9 months of child age as one of the retention strategies.

Main Measures and Outcomes

As stated in the published study protocol,21 at 6 months of age the main outcomes included infant feeding practices (ie, breastfeeding status, timing of introduction of solid foods, and cup feeding) and tummy time (ie, time of initiating tummy time and frequency of tummy time). At 12 months of age, the main outcomes included breastfeeding status, having family meals together, the use of food as a reward, having a bottle at bedtime, and cup use, as well as play time and screen time. The questionnaires used for the outcome assessment were the same as those in the previous HBT6,24,25,26 and can be found in eAppendix 3 in Supplement 2. Sociodemographic data were also collected using standard New South Wales Health Survey questions27 (Table 1). Data on the reach of the intervention, including the numbers of participants who received telephone support sessions or SMS messages, were monitored and recorded.

Table 1. Mothers’ Characteristics at Baseline by Group Allocation.

| Variable | Mothers, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1155) | Telephone support (n = 386) | SMS support (n = 384) | Control (n = 385) | |

| Mother’s age, y | ||||

| 16-24 | 97 (8) | 33 (9) | 33 (9) | 31 (8) |

| 25-29 | 272 (24) | 92 (24) | 81 (21) | 99 (26) |

| 30-34 | 442 (38) | 135 (35) | 162 (42) | 145 (38) |

| 35-39 | 270 (23) | 102 (26) | 87 (23) | 81 (21) |

| 40-49 | 74 (7) | 24 (6) | 21 (5) | 29 (8) |

| Country of birth | ||||

| Australia | 425 (37) | 143 (37) | 145 (38) | 137 (36) |

| Other | 730 (63) | 243 (63) | 239 (62) | 248 (64) |

| Language spoken at home | ||||

| English | 622 (54) | 207 (54) | 204 (53) | 211 (55) |

| Other | 533 (46) | 179 (46) | 180 (47) | 174 (45) |

| Annual household income, A$a | ||||

| <40 000 | 136 (12) | 47 (12) | 44 (12) | 45 (12) |

| 40 000-79 999 | 252 (22) | 82 (21) | 80 (21) | 90 (23) |

| ≥80 000 | 639 (55) | 213 (55) | 224 (58) | 202 (53) |

| Did not know or refused to answer | 128 (11) | 44 (12) | 36 (9) | 48 (12) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed (employed or paid or unpaid maternity leave) | 711 (62) | 244 (63) | 247 (64) | 220 (57) |

| Other | 443 (38) | 142 (37) | 137 (36) | 164 (43) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or de facto partner | 1075 (93) | 353 (91) | 360 (94) | 362 (94) |

| Other | 79 (6.9) | 32 (8) | 24 (6) | 23 (6) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Up to HSC to TAFE or diploma | 392 (34) | 126 (33) | 125 (33) | 141 (37) |

| University | 761 (66) | 260 (67) | 258 (67) | 243 (63) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Father’s employment status | ||||

| Employed | 1028 (89) | 336 (87) | 346 (90) | 346 (90) |

| Other | 100 (9) | 36 (9) | 31 (8) | 33 (8) |

| Unknown | 27 (2) | 14 (4) | 7 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Father’s educational level | ||||

| Up to HSC to TAFE or diploma | 451 (39) | 150 (39) | 144 (37) | 157 (41) |

| University | 653 (57) | 211 (55) | 229 (60) | 213 (55) |

| Unknown | 51 (4) | 25 (6) | 11 (3) | 15 (4) |

| First-time mother | ||||

| No | 531 (46) | 177 (46) | 170 (44) | 184 (48) |

| Yes | 624 (54) | 209 (54) | 214 (56) | 201 (52) |

Abbreviations: HSC, higher school certificate (year 12); SMS, short message service; TAFE, technical and further education.

To convert Australian dollars to US dollars, multiply by 0.61826.

Sample Size

Because this study was part of a 2-year, 3-group RCT, the sample size was based only on the outcome at 24 months of child age (ie, body mass index z score). In the published study protocol,21 a sample size of 1056 was required at baseline. This size was based on detecting a difference in the mean body mass index z score of 0.29 units between each intervention group and the control group at 2 years of age with 80% power and a 5% level of significance, allowing for a 25% loss to follow-up.

Blinding

Outcome data at 6 and 12 months were collected by a market survey company using a computer-assisted telephone interview. The interviewers were unaware of the research hypotheses and were blinded to treatment allocation. In addition, participating mothers were blinded to the specific details of the research hypotheses and were asked not to disclose treatment allocation during the assessment interviews.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata, version 13 (StataCorp LLC). The intention-to-treat principle was applied for all data analyses (ie, we compared the outcomes based on participants’ initial group allocations at baseline regardless of whether they received the interventions [telephone or SMS support] or not).

To address potential bias due to missing data and loss to follow-up, 3 steps were taken in comparing the outcomes. First, in complete-case analysis, we conducted comparisons of the outcomes between 1 of the intervention groups and the control group (ie, telephone support vs control and SMS support vs control) using Pearson χ2 tests. Second, we used multiple logistic regression models to adjust for recruitment sites to determine the intervention effects. Third, multiple logistic regression models with multiple imputation were used to confirm the intervention effects. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was calculated with the 95% CI and P value. All P values were 2 sided, significance was set at P < .05, and the P values were further adjusted using Bonferroni correction to account for multiple testing.

Multiple imputation was conducted using chained equations to impute missing values. We imputed all missing outcome values at 6 and 12 months of child age for a full intention-to-treat analysis of all 1155 participants. The imputation model predicting missing outcome values was based on all plausible observed values of outcomes and covariates at baseline and the 6-month and 12-month follow-up periods. We used 20 imputations that have a relative efficiency of more than 99% and a power falloff of less than 1%.28 We then calculated the proportions for binary outcomes using Stata’s “mi estimate” command and AORs of each of the binary outcomes for those in the telephone support and SMS support groups compared with the control group after adjustments for recruitment sites, as we did for the complete-case analysis models.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Follow-up

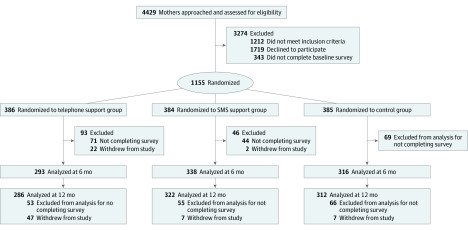

Of the 4429 pregnant women initially approached to participate, 3217 were eligible, and 1498 consented to participate in the study. Of those who gave consent, 1155 (77%) were randomized after completion of the baseline survey, and 343 (23%) were excluded owing to noncompletion of the baseline survey. As shown in the Figure, 1155 women were randomized into either the telephone support group (n = 386), SMS support group (n = 384), or control group (n = 385). Of 1155 mothers, 947 (82%) completed telephone surveys at 6 months (mean [SD] age, 32.5 [5.0] years), and 920 (80%) completed telephone surveys at 12 months, with 864 (75%) completing both surveys. At 6 months, there were 293 mothers (76%) in the telephone support group, 338 mothers (88%) in the SMS support group, and 316 (82%) mothers in the control group. At 12 months, there were 286 mothers (74%) in the telephone support group, 322 mothers (84%) in the SMS support group, and 312 mothers (81%) in the control group. At 6 months, 208 mothers either did not complete the telephone survey or withdrew from the study; at 12 months, 235 mothers either did not complete the telephone survey or withdrew from the study. More mothers from the telephone support group (n = 47) withdrew from the study than the mothers from either the SMS support group (n = 7) or the control group (n = 7) (Figure).

Figure. CONSORT Diagram.

SMS indicates short message service.

Table 1 shows that there were no significant differences in maternal characteristics between any of the 3 groups at baseline. eTable 1 in Supplement 2 also shows comparisons of the characteristics between the mothers who did and the mothers who did not complete the follow-up surveys at 6 and 12 months of child age.

Main Outcomes Using Multiple Imputation With Adjustments

Table 2 shows the comparisons of main outcomes between the telephone support, SMS support, and control groups at 6 and 12 months.29 At 6 months, compared with the control group, the telephone support group had greater odds of appropriate timing (ie, 6 months) of introducing solid foods (AOR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.22-2.32]), practicing tummy time within 4 weeks after birth (AOR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.18-2.25]), and drinking from a cup (AOR, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.12-2.13]). These findings were confirmed by multiple logistic regression models. The SMS group had a higher rate of appropriate timing of introducing solid foods than the control group, but it was no longer statistically significant after Bonferroni correction.

Table 2. Comparisons of Main Outcomes Between Each of the Intervention Groups and Control Group at 6 and 12 Months of Agea.

| Outcomeb | Participants, No. (%) | aOR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone support (n = 386) | Control (n = 385) | SMS support (n = 384) | Telephone support vs control | SMS support vs control | |

| At 6 mo | |||||

| Breastfeeding | |||||

| Exclusive | 26 (7) | 15 (4) | 23 (6) | 1.80 (0.83-1.13) | 1.27 (0.88-1.82) |

| Current | 271 (70) | 260 (68) | 271 (71) | 1.14 (0.80-1.64) | 1.08 (0.91-1.27) |

| Introduction of solid foods at 6 mo | 184 (48) | 135 (35) | 165 (43) | 1.68 (1.22-2.32)c | 1.19 (1.01-1.39) |

| Age of starting tummy time, <4 wk | 229 (59) | 182 (47) | 176 (46) | 1.63 (1.18-2.25)c | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) |

| Tummy time frequency, every day | 348 (90) | 343 (89) | 350 (91) | 1.11 (0.64-1.93) | 1.13 (0.87-1.47) |

| Drinking from cup | 167 (43) | 127 (33) | 154 (40) | 1.54 (1.12-2.13)c | 1.15 (0.98-1.35) |

| At 12 mo | |||||

| Current breastfeeding | 190 (49) | 169 (44) | 188 (49) | 1.25 (0.91-1.72) | 1.11 (0.95-1.30) |

| Drinking from cup | 321 (83) | 294 (76) | 311 (81) | 1.53 (1.02-2.29) | 1.13 (0.92-1.39) |

| No bottle at bedtime | 229 (59) | 177 (46) | 226 (59) | 1.73 (1.23-2.42)c | 1.29 (1.10-1.51)c |

| Having a meal togetherd | 283 (73) | 302 (78) | 277 (72) | 0.75 (0.50-1.13) | 0.84 (0.70-1.01) |

| Having a family meald | 239 (62) | 187 (49) | 211 (55) | 1.71 (1.23-2.39)c | 1.13 (0.97-1.32) |

| No use of food for reward | 291 (75) | 266 (69) | 276 (72) | 1.37 (0.96-1.97) | 1.08 (0.90-1.28) |

| Child active time, >2 h/d | 346 (90) | 322 (84) | 330 (86) | 1.68 (1.07-2.66) | 1.09 (0.88-1.35) |

| Never having screen time | 143 (37) | 95 (25) | 134 (35) | 1.80 (1.28-2.53)c | 1.28 (1.08-1.52)c |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for recruitment sites); SMS, short message service.

Intention-to-treat analysis with multiple imputations.

Based on the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Infant Feeding Guidelines.29

P < .05 with Bonferroni correction.

“Having a meal together” refers to the parents and child sitting and eating a meal together. “Having a family meal” refers to a child eating the same meal as their parents.

At 12 months, compared with the control group, the telephone support group had greater odds of children having no bottle at bedtime (AOR, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.23-2.42]), having a family meal (AOR, 1.71 [95% CI, 1.23-2.39]), and having no screen time (AOR, 1.80 [95% CI, 1.28-2.53]) (Table 2).29 These findings were still statistically significant after multiple logistic regression models with AORs greater than 1 and P < .05 after Bonferroni correction. The telephone support group showed higher rates of children drinking from a cup and having active time for more than 2 hours per day, but these rates were not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction. The SMS support group also had greater odds of children having no bottle at bedtime (AOR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.10-1.51]) and having no screen time (AOR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.08-1.52]). Rates of breastfeeding at 12 months were higher in the telephone support group (190 of 386 [49%]) and the SMS support group (188 of 384 [49%]) than in the control group (169 of 385 [44%]), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Main Outcomes in Complete-Case Analysis With Adjustments

eTable 2 in Supplement 2 shows comparisons of main outcomes between the telephone support, SMS support, and control groups using complete-case analysis. The results were very similar to those in Table 2 based on multiple imputation.29

Process Indicators

Table 3 shows the numbers and percentages of participating mothers who received telephone support sessions or SMS messages. Not all mothers were able to participate in the telephone support sessions. Only 234 mothers (61%) received the first telephone session, only 337 mothers (87%) received the second telephone session, only 283 mothers (73%) received the third telephone session, only 245 mothers (63%) received the fourth telephone session, only 270 mothers (70%) received the fifth telephone session, and only 264 mothers (68%) received the sixth telephone session. A total of 15 participants opted out from SMS intervention by the end of 12 months. The scheduling SMS system does not allow us to identify at what time point the participants decided to opt out. Overall, the SMS intervention reached 369 participants (96%) in the SMS group.

Table 3. Process Indicators of Telephone and SMS Support.

| Support session | Participants, No./total No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Telephone support | |

| 1 | 234/386 (61) |

| 2 | 337/386 (87) |

| 3 | 283/386 (73) |

| 4 | 245/386 (63) |

| 5 | 270/386 (70) |

| 6 | 264/386 (68) |

| SMS supporta | 370/384 (96) |

Abbreviation: SMS, short message service.

Data show only overall number of participants who remained in SMS support group by end of intervention because the time point when participants decided to opt out could not be determined by the scheduling SMS system.

Discussion

Principal Findings of the Study

This 3-group RCT found that telephone support may increase desired health behaviors (such as introducing solid foods at the recommended age, cup use, and practicing tummy time at an earlier age) and may also increase rates of having no bottle at bedtime and no screen time, as well as having a family meal at 12 months. The study also found that SMS support may lead to increased rates of having no bottle at bedtime and no screen time. However, neither intervention showed an effect on breastfeeding rate. Furthermore, the findings suggest that telephone support might be more effective than SMS support in promoting other healthy feeding practices, such as cup use and appropriate timing of introducing solid foods.

Meaning of the Study

Consistent with previous empirical evidence,14,15,16,17 this study suggests that the nurse-led telephone support interventions may improve some healthy infant feeding practices, particularly the appropriate timing of introducing solid foods and cup use. The results also demonstrate that both telephone and SMS interventions can reduce early exposure to screen time. With current recommendations detailing that children younger than 2 years of age should not be exposed to screen time,30 this research presents potential intervention approaches for targeting these guidelines. The study’s findings are particularly important in informing the development of future telephone or SMS support programs for mothers as part of an early obesity prevention strategy.

Unlike the previous HBT,6 which found significant improvement in breastfeeding through home visits, neither the telephone nor SMS support significantly increased breastfeeding rates. Several trials that have used telephone support to enhance breastfeeding outcomes have found only short-term (<6 months) effects of the intervention. For instance, a lactation counseling intervention delivered by telephone was effective in increasing breastfeeding rates at 1 month after birth but not at 4 and 6 months.17 Similarly, another telephone intervention led by a lactation consultant found no significant effect on breastfeeding duration at 3 months after birth despite a significant effect at 1 month.31 Another 2 telephone interventions found no significant differences in breastfeeding outcomes between the intervention and control groups, even in the short term.14,15

However, our study observed that mothers in both intervention groups could be more likely to breastfeed at 12 months than mothers in the control group, although the difference was not statistically significant. This lack of significance could be owing to the sample size that was not powered to detect smaller differences. One-year postpartum breastfeeding is an important milestone because every additional breastfeeding week is associated with less illness among infants.32

What the Study Adds

The study findings support those of the previous HBT using a home visiting model that showed that a nurse-led staged intervention improved infant feeding practices and tummy time.6 The unique features of these studies provide timely, needed health information for mothers according to child development stages of feeding and movement. Our findings support that it is feasible and effective to improve infant feeding practices and tummy time using telephone support.

In this study, telephone support seemed more effective, but it might be less sustainable as more mothers in this group withdrew from the study compared with the SMS support group and the control group. The higher withdrawal rate could reflect mothers’ lack of availability to participate in the telephone support sessions, which would require 30 to 60 minutes of their time. In addition, approximately 88% of the population in Australia in 2017 owned a smartphone,33 and it can be anticipated that the number of current cell phone users would be higher. Thus, there is potential for the use of SMS to deliver health intervention messages.

Unanswered Questions and Future Research

This study detected a potential effect of the telephone or SMS support on breastfeeding outcomes at 12 months. Another RCT found that mothers who received more telephone support were more likely to breastfeed than women who received less telephone support, although no significant difference was found in the overall breastfeeding rate between the intervention and control groups.14 The effect of a greater frequency of telephone calls or SMS messages as a method of support for infant feeding outcomes is worth investigating.

Our findings suggest that telephone support might be more effective than SMS messages in improving infants’ feeding practice and tummy time. This finding may be attributed to the interactive component of the telephone support. One RCT showed that an SMS intervention was effective in improving breastfeeding duration using automated 2-way SMS messaging.19 Some studies suggest that a multifaceted intervention may intensify outcomes.16,18 An intervention that combines telephone support and SMS support, which could be universally delivered and remains cost-effective, has the potential to produce greater effects. This potential, however, warrants further investigation.34 In addition, with the limited studies available on the relative costs of different types of interventions in this area, it is important for future research to examine the costs and cost-effectiveness of various intervention approaches (eg, face-to-face vs telephone or SMS support).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has some strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale RCT that examines the effects of either telephone or SMS support on a range of infants’ health behaviors. Our intervention commenced in the antenatal period; early contact allowed us the opportunity to discuss and improve mothers’ feeding knowledge and intention and to address their concerns in a timely manner. Our nurse-led intervention also shows potential for making a difference in healthy infant feeding practices and tummy time. Child and family health nurses delivered telephone support sessions. In addition to their base professional training, they were trained in motivational interviewing and how to address additional psychosocial issues associated to infants’ health and behavioral issues. The research protocol was published prior to study commencement. The participation rate was high, with a mean of 81% at follow-up periods.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, we were not able to fully address the many social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors that are likely to be associated with infant feeding practices. Second, the design of the telephone intervention required 6 contacts between the nurses and the participants; however, approximately 30% of participants did not receive all of the telephone support sessions, which may have reduced the effect of the telephone support. Third, the sample size estimate was not based on the main outcomes assessed, nor was it powered enough for comparing effects between the interventions. Fourth, this study was also limited by the use of self-reported outcome measures.

Conclusions

Both the telephone and SMS interventions were effective in reducing screen time and bottle use at bedtime, with telephone support offering greater effects on improving some infant feeding practices and tummy time. A combination of both delivery modes may intensify the health outcomes. There is a need for future research to explore this potential.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparisons of the Participants’ Characteristics Between Those Who Did and Did Not Complete the Follow-up Surveys at 6 and 12 Months of Child Age

eTable 2. Comparisons of Main Outcomes Between Each of the Intervention Groups and Control Group at 6 and 12 Months of Age (Complete-Case Analysis)

eAppendix 1. Sample of Telephone Transcript (Stage One)

eAppendix 2. Time Points and SMS Messages

eAppendix 3. Main Outcomes and Assessment Questions

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Grummer-Strawn LM, Li R, Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, Fein SB. Infant feeding and long-term outcomes: results from the year 6 follow-up of children in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II. Pediatrics. 2014;134(suppl 1):S1-S3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perrine CG, Galuska DA, Thompson FE, Scanlon KS. Breastfeeding duration is associated with child diet at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134(suppl 1):S50-S55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646I [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Accessed October 12, 2018. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/end-childhood-obesity/en/

- 4.World Health Organization Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age. World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koren A, Kahn-D’angelo L, Reece SM, Gore R. Examining childhood obesity from infancy: the relationship between tummy time, infant BMI-z, weight gain, and motor development—an exploratory study. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(1):80-91. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Flood VM. Effectiveness of an early intervention on infant feeding practices and “tummy time”: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):701-707. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell KJ, Lioret S, McNaughton SA, et al. A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity risk behaviors: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):652-660. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D, Magarey A. Outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e109-e118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Gross MB, Scheinmann R, Messito MJ. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care–based child obesity prevention intervention on infant feeding practices. J Pediatr. 2016;174:171-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle K, Flood VM. Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children’s BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):81-88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):419-434. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:393-415. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunik M, Shobe P, O’Connor ME, et al. Are 2 weeks of daily breastfeeding support insufficient to overcome the influences of formula? Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(1):21-28. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoddinott P, Craig L, Maclennan G, Boyers D, Vale L; NHS Grampian and the University of Aberdeen FEST Project Team . The FEeding Support Team (FEST) randomised, controlled feasibility trial of proactive and reactive telephone support for breastfeeding women living in disadvantaged areas. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000652. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugh LC, Serwint JR, Frick KD, et al. A randomized controlled community-based trial to improve breastfeeding rates among urban low-income mothers. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(1):14-20. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tahir NM, Al-Sadat N. Does telephone lactation counselling improve breastfeeding practices? a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):16-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flax VL, Negerie M, Ibrahim AU, Leatherman S, Daza EJ, Bentley ME. Integrating group counseling, cell phone messaging, and participant-generated songs and dramas into a microcredit program increases Nigerian women’s adherence to international breastfeeding recommendations. J Nutr. 2014;144(7):1120-1124. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.190124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallegos D, Russell-Bennett R, Previte J, Parkinson J. Can a text message a week improve breastfeeding? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:374. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0374-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Li M, Wen LM, et al. Effect of short message service on infant feeding practice: findings from a community-based study in Shanghai, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(5):471-478. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen LM, Rissel C, Baur LA, et al. A 3-arm randomised controlled trial of Communicating Healthy Beginnings Advice by Telephone (CHAT) to mothers with infants to prevent childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-4005-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekambareshwar M, Mihrshahi S, Wen LM, et al. Facilitators and challenges in recruiting pregnant women to an infant obesity prevention programme delivered via telephone calls or text messages. Trials. 2018;19(1):494. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2871-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, Alperstein G, Simpson JM. Intention to breastfeed and awareness of health recommendations: findings from first-time mothers in southwest Sydney, Australia. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen LM, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Baur LA. Awareness of breastfeeding recommendations and duration of breastfeeding: findings from the Healthy Beginnings Trial. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(4):223-229. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, Xu H, Simpson JM. Correlates of body mass index and overweight and obesity of children aged 2 years: findings from the Healthy Beginnings Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(7):1723-1730. doi: 10.1002/oby.20700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centre for Epidemiology and Research 2006 Report on Adult Health From the New South Wales Population Health Survey. New South Wales Department of Health, Australia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):206-213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health and Medical Research Council Infant Feeding Guidelines. National Health and Medical Research Council; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Government Department of Health Inactivity and screen time. Updated 2012. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/gug-indig-hb~inactivitiy

- 31.Fallon AB, Hegney D, O’Brien M, Brodribb W, Crepinsek M, Doolan J. An evaluation of a telephone-based postnatal support intervention for infant feeding in a regional Australian city. Birth. 2005;32(4):291-298. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieterich CM, Felice JP, O’Sullivan E, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding and health outcomes for the mother-infant dyad. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):31-48. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deloitte Mobile consumer survey 2019. Accessed November 10, 2019. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/mobile-consumer-survey

- 34.Wen LM, Rissel C, Xu H, et al. Linking two randomised controlled trials for Healthy Beginnings: optimising early obesity prevention programs for children under 3 years. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):739. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7058-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Comparisons of the Participants’ Characteristics Between Those Who Did and Did Not Complete the Follow-up Surveys at 6 and 12 Months of Child Age

eTable 2. Comparisons of Main Outcomes Between Each of the Intervention Groups and Control Group at 6 and 12 Months of Age (Complete-Case Analysis)

eAppendix 1. Sample of Telephone Transcript (Stage One)

eAppendix 2. Time Points and SMS Messages

eAppendix 3. Main Outcomes and Assessment Questions

Data Sharing Statement