Abstract

Glutamic acid, an abundant nonessential amino acid, was converted into 2‐pyrrolidone in the presence of a supported Ru catalyst under a pressurized hydrogen atmosphere. This reaction pathway proceeded through the dehydration of glutamic acid into pyroglutamic acid, subsequent hydrogenation, and the dehydrogenation–decarbonylation of pyroglutaminol into 2‐pyrrolidone. In the conversion of pyroglutaminol, Ru/Al2O3 exhibited notably higher activity than supported Pt, Pd, and Rh catalysts. IR analysis revealed that Ru can hydrogenate the formed CO through dehydrogenation–decarbonylation of hydroxymethyl groups in pyroglutaminol and can also easily desorb CH4 from the active sites on Ru. Furthermore, Ru/Al2O3 showed the highest catalytic activity among the tested catalysts in the conversion of pyroglutamic acid. Consequently, the conversion of glutamic acid produced a high yield of 2‐pyrrolidone by using the supported Ru catalyst. This is the first report of this one‐pot reaction under mild reaction conditions (433 K, 2 MPa H2)„ which avoids the degradation of unstable amino acids above 473 K.

Keywords: 2-pyrrolidone, glutamic acid, hydrogenation, pyroglutamic acid, ruthenium

Glutamic acid, an abundant nonessential amino acid, is converted into 2‐pyrrolidone through successive reactions over Ru/Al2O3 under pressurized hydrogen atmosphere. The conversion of pyroglutaminol into 2‐pyrrolidone is a key reaction in the reaction pathway, and Ru/Al2O3 exhibits high activity owing to the remarkable effect of CO activation.

Introduction

The biorefinery concept has attracted attention as an essential research subject because of the need for greener alternative renewable resources to replace finite petroleum. Various biomass compounds are promising resources to be converted into essential chemicals through catalytic processes. Oxygen‐containing chemical intermediates have been produced from carbohydrates and fatty oils. In contrast, only a few examples have been reported of the conversion of organic nitrogen‐containing compounds, the importance of which as intermediates for polymers, drugs, organic semiconductors, and dyes is well known.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Amino acids in proteins and their components are promising as feedstocks of amines, amides, and nitriles, which have conventionally been produced by insertion of nitrogen into compounds of petrochemical origin; typically, ammonia has been utilized for this purpose. The use of amino acids as feedstocks will significantly reduce the energy consumption in the production of nitrogen‐containing functional compounds.6, 7, 8, 9 Ammonia‐based or ‐derived fertilizers are used in the majority of modern agriculture, but the utilization efficiency of such fertilizers tends to be low. Thus, one can argue that the replacement of the nitrogen source is explicitly linked to energy savings.

Glutamic acid is the most abundant amino acid in plant biomass. Bioethanol production from maize or wheat forms crude proteins in 20 % dried distiller's grains, which are soluble in water and contain 20 % l‐glutamic acid.10, 11, 12, 13 The energy and resource demands for the extraction and purification of l‐glutamic acid are not necessarily trivial. In addition, the U.S. Department of Energy has identified glutamic acid as one of the “Top 12” sugar‐based chemical building blocks for biochemical or chemical conversions; the list contains only two species of nitrogen‐containing chemicals.14 Approximately 2 million tons of glutamic acid are produced by fermentation from saccharides per year. Thus, one can safely say that the nitrogen‐containing compound that is most abundantly supplied at present is glutamic acid from plant biomass.

One amine and two carboxy groups in the molecule enable glutamic acid to be converted into a wide range of compounds. An enzyme, glutamic acid α‐decarboxylase, converts glutamic acid and its analogues into γ‐aminobutylic acid, which is transformed into 2‐pyrrolidone through a lactamization.15 In addition, it was reported that succinonitrile and acrylonitrile were formed from the amino acid through multistep reactions with homogeneous catalysts.16, 17 Heating glutamic acid over 393 K immediately produces pyroglutamic acid through dehydration–cyclization. Thus, obtained pyroglutamic acid was transformed into chemical commodities in some previous reports.18 Succinimide was synthesized from pyroglutamic acid through decarboxylation and oxidation by using AgNO3 as a catalyst and S2O8 2− as an oxidant.19 Also, hydrogenation of the carboxyl group in pyroglutamic acid produces pyroglutaminol, which can be converted into prolinol in an acidic solution under high temperature and H2 pressure.20 Recently, it was found that 2‐pyrrolidone was obtained through decarboxylation of pyroglutamic acid on Pd/Al2O3 in aqueous solution at 523 K and under inert atmosphere (N2).21 In this reaction, low pH improved the yield of 2‐pyrrolidone from glutamic acid. Biobased conversion of glutamic acid with decarboxylase produced γ‐aminobutylic acid, which can be transformed into 2‐pyrrolidone by intramolecular condensation at 473–513 K.22, 23

2‐Pyrrolidone has played important roles in the chemical industry. It is a convenient solvent with a high boiling point and is miscible with water and most organic solvents. As a chemical platform compound, the ring‐opening polymerization of five‐membered lactam forms nylon 4, which is a biodegradable polymer.24 Also, polyvinylpyrrolidone, a water‐soluble polymer useful as a solubilizer and dispersant, is synthesized from N‐vinyl‐2‐pyrrolidone.25 Various pharmaceutical compounds are also 2‐pyrrolidone derivatives. Typically, 2‐pyrrolidone is produced from γ‐butyrolactone and NH3, which are available from petrochemical feedstocks. Very little research on the alternative biobased process has, to the best of our knowledge, been reported.21, 22, 23

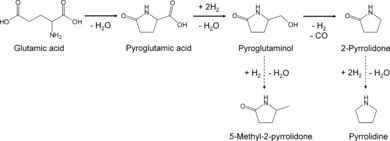

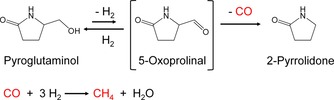

Herein, we describe an approach for producing 2‐pyrrolidone from glutamic acid through hydrogenation of pyroglutamic acid into pyroglutaminol under high pressure of H2 (Scheme 1). Supported noble metals such as Pt/Al2O3 and Pd/Al2O3 are typically used as the catalysts for hydrogenation/dehydrogenation reactions. In fact, Pd/Al2O3 has been reported to be an active catalyst for the decarboxylation of glutamic acid under inert atmosphere.21 Therefore, Pt/Al2O3 and Pd/Al2O3 can be considered as the benchmarks, and the catalytic activities of other supported metals are compared with them. Our working hypothesis was that pyroglutaminol could be converted into 2‐pyrrolidone by eliminating the hydroxymethyl group. In this study, Ru/Al2O3 showed a remarkably high yield of 2‐pyrrolidone in pyroglutaminol conversion. IR analysis revealed the reason for the higher activity of Ru/Al2O3 than Pt‐, Pd‐, or Rh‐loaded catalysts. More importantly, the formation of 2‐pyrrolidone from glutamic acid or pyroglutamic acid achieved a high yield under milder reaction conditions in H2 atmosphere than the other transformations of glutamic acid, in which unstable amino acids are decomposed above 473 K.

Scheme 1.

Reaction pathway for the formation of 2‐pyrrolidone from glutamic acid and side reactions.

Results and Discussion

Structure of the catalyst

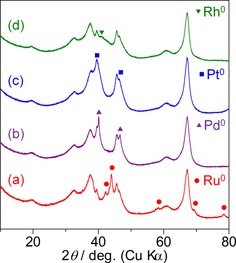

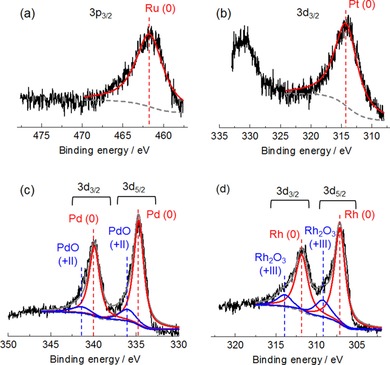

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of prepared noble‐metal catalysts. Intact peaks observed for all catalysts indicate γ‐Al2O3 as a support. The marked peaks show metal species of the elements with a diameter of <10 nm. The valence state of the surface of the catalysts was investigated by using X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Figure 2). The Ru 3p3/2 spectrum (a) of Ru/Al2O3 shows only one peak at 461.7 eV, assigned to Ru (oxidation state: 0, as metal).26 Similarly, the peak at 314.5 eV in the Pt 3d3/2 spectrum (c) of Pt/Al2O3 was attributed to Pt metal.27 The surface Ru and Pt on the catalysts were completely reduced into metal. The spectrum of Pd in the region of 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 for Pd/Al2O3 (b) is composed of an intense doublet of peaks at 334.3 and 339.5 eV and a weak doublet of peaks at 335.6 and 341.0 eV, which were assigned to Pd metal and Pd2+ in PdO, respectively.28 In the spectrum of Rh in the similar energy level to Pd, two types of doublet peaks were attributed to Rh metal (307.1 and 311.8 eV) and Rh3+ in Rh2O3 (309.2 and 313.9 eV).29 Pd and Rh metals existed with small amount of oxides.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns for (a) Ru/Al2O3, (b) Pd/Al2O3, (c) Pt/Al2O3, and (d) Rh/Al2O3.

Figure 2.

XPS spectra of (a) Ru 3p3/2 region in the Ru catalyst, (b) Pt 3d5/2 region in the Pt catalyst, (c) Pd 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 regions in the Pd catalyst, and (d) Rh 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 regions in the Rh catalyst.

The TEM images (Figure 3) indicated that the particle size of all noble metals had a narrow distribution, but a slightly wider distribution was observed for Pd. The average particle diameters were 2.8–3.5 nm, and the order was Rh<Pt<Pd<Ru. The noble metals were uniformly dispersed on the support, which is consistent with the XRD results. The amount of CO chemisorbed on Rh was more than three times that on the other catalysts (Table 1). The average particle diameters of the metals were also calculated from the CO chemisorption. The order was Rh<Pt<Ru<Pd, indicating dissimilar dimensions to those observed by TEM owing to the inclusion of coarse particles on Pd/Al2O3.

Figure 3.

TEM images and particle size distributions of Al2O3‐supported noble‐metal catalysts. * indicates the average particle diameter.

Table 1.

CO chemisorption results on the noble‐metal catalysts.

|

Metal |

Chemisorbed amount [mmol g−1] |

Metal dispersion [%] |

Average particle diameter [nm] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pt |

0.058 |

22.8[a] |

5.0[a] |

|

Rh |

0.208 |

42.9[a] |

2.6[a] |

|

Pd |

0.072 |

15.2[a] |

7.4[a] |

|

Ru |

0.068 |

23.1[b] |

5.7[b] |

[a] The stoichiometry was assumed as CO/metal=1. [b] The stoichiometry was assumed as CO/Ru=0.6.

Conversion of pyroglutaminol and pyroglutamic acid over noble‐metal catalysts

Conversion of pyroglutaminol into 2‐pyrrolidone

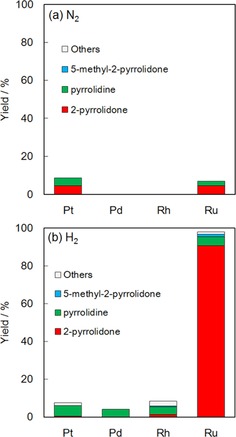

Figure 4 compares the yield of products over the supported noble‐metal catalysts at 433 K for 1 h in 1 MPa of two different atmospheres, that is, (a) N2 and (b) H2. In N2, all employed catalysts showed negligible yields of products including the desired one, that is, 2‐pyrrolidone, and the potential byproduct from the assumed sequential reaction (Scheme 1), that is, pyrrolidine. In H2, Ru/Al2O3 exhibited extremely high activity for the formation of 2‐pyrrolidone whereas all other catalysts showed little activity. Time courses of Ru/Al2O3 (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information) revealed that pyroglutaminol was virtually fully converted into 2‐pyrrolidone in 10 min, and the intermediate was not detected. Not only was the apparent activity high as described above, but the turnover frequency (TOF) was also high for Ru/Al2O3 in 1 MPa H2, as shown in Table 2. It is noteworthy that the TOF for Ru/Al2O3 in H2 was more than 200 times higher than those for the other noble‐metal catalysts. Over Ru/Al2O3, byproducts such as pyrrolidine and 5‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone, predicted in Scheme 1, were not significantly observed in the liquid products. As shown in Figure S2 (in the Supporting Information), the analysis of gaseous compounds in the reactor after the reaction over Ru/Al2O3 in 1 MPa H2 at 433 K for 1 h detected H2 and CH4 with air components (O2 and N2) as contaminants during the gas sampling, whereas CO (retention time: 0.49 and 7.75 min) and CO2 (1.23 min) were not detected at all.

Figure 4.

Yield of products in the conversion of pyroglutaminol over supported metal catalysts in an atmosphere of (a) N2 and (b) H2. Reaction conditions: pyroglutaminol (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), catalyst (0.2 g), initial pressure 1 MPa, 433 K, 1 h.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of the noble‐metal catalysts.

|

Metal |

Reaction rate[a] [mmol gcat −1 h−1] |

TOF[b] [h−1] |

|---|---|---|

|

Pt |

0.03 |

0.4 |

|

Rh |

0.08 |

0.4 |

|

Pd |

0 |

0 |

|

Ru |

5.89 |

86.6 |

[a] Rate for 2‐pyrrolidone formation. [b] TOF values were calculated by dividing the rate for 2‐pyrrolidone formation by the amount of chemisorbed CO on the catalysts as shown in Table 1.

The elimination of hydroxymethyl groups from pyroglutaminol yielding 2‐pyrrolidone was found to proceed in pressurized H2 over Ru/Al2O3, but not in N2 nor over the other noble‐metal catalysts. Although the reaction formula (−CH2OH→H+CH2O) indicates the formation of CO and H2 or some oxygen‐containing compounds, CH4 was mainly found in the gaseous products.

IR measurements of species on the catalysts formed from pyroglutaminol

After the adsorption of pyroglutaminol at low temperature, the thermal behavior of the adsorbed species in Ar or H2 (6 %)/Ar flow was investigated with in situ IR, as shown in Figure S3 (in the Supporting Information). On all employed noble‐metal catalysts in both atmospheres, the bands resulting from stretching of O−H in hydroxymethyl groups (≈3500 cm−1), stretching of N−H in amide groups (≈3050 cm−1), stretching of C=O in amide groups (1570 cm−1), and bending of CH2 in intact and transformed pyroglutaminol molecules (1460 cm−1) were observed; it is possible that these bands overlap the bending bands of N−H (1490–1580 cm−1).30 In addition, weak bands owing to plane bending of O−H coupled with wagging of adjacent CH2 in intact pyroglutaminol molecules (1420 and 1330 cm−1) and stretching of C=O in aldehyde groups formed from hydroxymethyl groups (1670 cm−1) were observed.

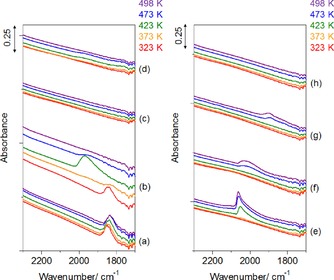

Besides the above bands commonly observed, a characteristic absorption was found at 1800–2300 cm−1, as enlarged in Figure 5, and assignments were made according to the literature (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information).31, 32, 33, 34, 35 The adsorbed species itself, and its change in absorbance by varying the temperature/atmosphere were dependent on the noble metal, as follows.

Figure 5.

Enlarged IR spectra of adsorbed species, formed from pyroglutaminol, on the catalysts during the ramping process in the flow of Ar (a, c, e, g) or H2 (6 vol. %)/Ar (b, d, f, h). (a, b) Ru/Al2O3, (c, d) Rh/Al2O3, (e, f) Pt/Al2O3, and (g, h) Pd/Al2O3.

On Ru/Al2O3 in Ar (Figure 5 a), bridge‐type CO adsorbed on Ru31 was found at 1850 cm−1. However, it was observed that this species desorbed above 373 K in H2/Ar (Figure 5 b); in addition, CO linearly adsorbed on isolated Ru31, 32 was found at 1973 cm−1 at 423 K but desorbed above 473 K. On Rh/Al2O3 in Ar (Figure 5 c) and H2/Ar (Figure 5 d), no band was observed in the enlarged spectra. On Pt/Al2O3 in Ar (Figure 5 e), CO linearly adsorbed on Pt0 was observed at 2055 cm−1,33 and this band increased with temperature. In H2/Ar (Figure 5 f), CO linearly adsorbed on Pt carbonyl hydride was found at 1990–2020 cm−1.34, 35 On Pd/Al2O3 in Ar (Figure 5 g), bridge‐type CO adsorbed on Pd34 was found at 1896 cm−1 above 473 K. However, this weak band was not observed in H2/Ar (Figure 5 h).

Conversion of pyroglutamic acid to 2‐pyrrolidone

The reaction of pyroglutamic acid was performed at 433 K for 2 h in 2 MPa H2 (Figure 6). A high yield of 2‐pyrrolidone was found over Ru/Al2O3. Pyroglutaminol, an intermediate in the pathway from pyroglutamic acid to 2‐pyrrolidone as demonstrated in the following section, was also observed, but the yields of byproducts such as 5‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone and pyrrolidine were small. In contrast, Pt, Pd, and Rh loaded on Al2O3 formed pyroglutaminol as the main product. This is in agreement with a literature report stating that the decarboxylation of pyroglutamic acid into 2‐pyrrolidone and carbon dioxide over Pd/Al2O3 in N2 did not proceed below 448 K, although it was observed at 523 K.21 In fact, in the present reaction conditions (433 K), the decarboxylation did not occur, but only hydrogenation of pyroglutamic acid proceeded. Rh/Al2O3 showed a higher yield of 2‐pyrrolidone than Pt‐ and Pd‐loaded catalysts, but yields of 2‐pyrrolidone over all these catalysts were clearly lower than over Ru/Al2O3.

Figure 6.

Yields of products in the conversion of pyroglutamic acid over metal catalysts under pressurized H2. Reaction conditions: pyroglutamic acid (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), catalyst (0.2 g), initial pressure 2 MPa, 433 K, 2 h.

Effect of reaction conditions on the conversion of pyroglutamic acid over Ru catalyst

Hereafter, the influence of the reaction conditions on the catalytic activity in this section was evaluated by using Ru/Al2O3. Figure 7 shows the conversion and selectivity of the products over Ru/Al2O3 as functions of reaction time in the transformation of pyroglutamic acid. Pyroglutaminol was mainly formed for the first 0.5 h, and then its selectivity decreased whereas 2‐pyrrolidone selectivity increased up to 2 h, indicating that pyroglutaminol was an intermediate between pyroglutamic acid and 2‐pyrrolidone, as postulated in Scheme 1. At >2 h, pyrrolidine selectivity was found to increase with a decrease of 2‐pyrrolidone selectivity, suggesting that pyrrolidine was formed from 2‐pyrrolidone by subsequent reaction (as drawn in Scheme 1) although the yield of parallel products such as 5‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone remained low.

Figure 7.

Time courses of the conversion and selectivities of the products in the transformation of pyroglutamic acid. Reaction conditions: pyroglutamic acid (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), Ru/Al2O3 (0.2 g), initial pressure 2 MPa H2, 433 K.

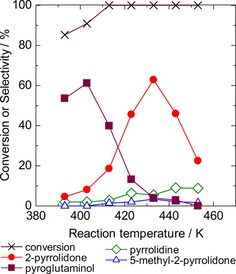

Figure 8 shows the influence of reaction temperature. At 393 K, the conversion was moderate, pyroglutaminol was the main product, and a small amount of 2‐pyrrolidone was formed. Raising the temperature to 433 K increased the selectivity of 2‐pyrrolidone with a decrease of the pyroglutaminol selectivity, supporting the idea that pyroglutaminol was the intermediate, and 2‐pyrrolidone was formed via pyroglutaminol. Other products, such as 5‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone and pyrrolidine, were hardly formed. Too high temperatures (>433 K) thoroughly decreased the 2‐pyrrolidone yield and increased the selectivity of pyrrolidine and other products.

Figure 8.

Influence of reaction temperature on the conversion and selectivities of the products in the transformation of pyroglutamic acid. Reaction conditions: pyroglutamic acid (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), Ru/Al2O3 (0.2 g), initial pressure 2 MPa H2, 2 h.

Figure 9 shows the influence of H2 pressure on the catalytic activities at 433 K for 2 h. As stated before, the reaction did not proceed without H2. Introduction of H2 up to 2 MPa generated reactivity. Pyroglutaminol was the main product at 0.5 MPa. It is noteworthy that the mass balance was low in these conditions, and it is presumed that the materials were adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst. The pressure of H2 increased the 2‐pyrrolidone selectivity. However, excess high pressure resulted in a low selectivity of 2‐pyrrolidone and high selectivity of pyrrolidine. Similar to the increase of reaction time and temperature, elevation of the H2 pressure was thus observed to enhance the extent of reaction.

Figure 9.

Influence of initial H2 pressure on the conversion and selectivities of the products in the transformation of pyroglutamic acid. Reaction conditions: pyroglutamic acid (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), Ru/Al2O3 (0.2 g), 433 K, 2 h.

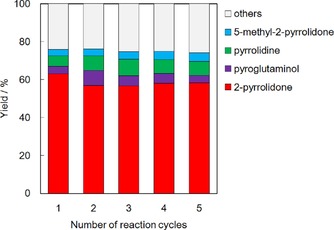

The reusability of Ru/Al2O3 was tested as shown in Figure 10. After each reaction run, the catalyst was washed thoroughly with water to remove the organic compounds from the surface and it was reused for the subsequent reaction run. No decrease in activity was displayed when the reaction was continued for five runs, showing the stability of Ru/Al2O3.

Figure 10.

Reusability tests of Ru/Al2O3. Reaction conditions: pyroglutamic acid (aq., 26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), catalyst (0.2 g), initial pressure 2 MPa H2, 433 K, 2 h.

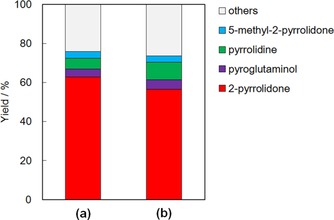

Conversion of glutamic acid over Ru/Al2O3

The catalytic activity for the conversion of glutamic acid is shown in Figure 11. The 2‐pyrrolidone yield was still high in this reaction, which was comparable with that in the conversion of pyroglutamic acid. No significant influence owing to the difference of reactants between glutamic acid and pyroglutamic acid was observed.

Figure 11.

Yield of products in the conversion of (a) pyroglutamic acid and (b) glutamic acid. Reaction conditions: reactant solution (26 mmol L−1, 50 mL), Ru/Al2O3 (0.2 g), initial pressure 2 MPa H2, 433 K, 2 h.

Discussion

In the above‐mentioned experiments, it was shown that the conversion of pyroglutamic acid into pyroglutaminol proceeded over various noble metals; more exactly, the activity of Pt and Rh for this step appeared higher than that of Pd. However, the next step from pyroglutaminol into 2‐pyrrolidone seems a difficult reaction and hence did not proceed over most catalysts for either pyroglutamic acid or pyroglutaminol as the reactant. Only Ru/Al2O3 smoothly catalyzed the elimination of the hydroxymethyl group from pyroglutaminol to form 2‐pyrrolidone without distinct side reactions. It is important to note that the reaction eliminated CO and H2 from the chemical formula, but the introduction of H2 generated and enhanced the activity on Ru/Al2O3. Probably, an undetectable other product in the reaction of pyroglutamic acid was formed by intermolecularly linking pyroglutamic acid and products and adsorbed on Ru/Al2O3.

After contact of pyroglutaminol with the catalyst, the in situ IR analysis indicated that linear CO was adsorbed on Pt. CO adsorption experiments indicated the larger chemisorption capacity of CO on Rh/Al2O3 than Pt/Al2O3, but in the in situ IR demonstrated that the formation of CO was more significant over Pt/Al2O3. In addition, Pd/Al2O3, which was not found to be active for the reaction of pyroglutaminol, showed slight adsorption of CO in the in situ IR spectrum. It is suggested that the decarbonylation of pyroglutaminol to form CO proceeded over Pt, but the formed CO was strongly adsorbed on the metal to prevent successive reaction; the adsorption of CO on such noble metals as Pt is often too strong to enable further catalytic activities of these metals.31, 36, 37 It is reasonable that the intensity of adsorbed CO in the IR spectrum was much larger on Pt than Rh, converse to the order of CO adsorption capacity, because the ability of Pt for decarbonylation of pyroglutaminol was higher than that of Rh. In addition, Pd has no activity in the pyroglutaminol conversion, meaning hardly any CO is formed.

However, bridge‐type CO was formed on Ru/Al2O3 in an inert atmosphere. Introduction of H2 diminished the bridge‐type CO and increased the linear‐type CO formation, which then desorbed. In addition, formation of CH4 was found in the H2 atmosphere. The introduction of H2 simultaneously generated the catalytic activity for pyroglutaminol conversion into 2‐pyrrolidone on Ru. It is known that the bridge‐type CO is more active than the linear‐type CO,31 and Ru had higher catalytic activity than Rh, Pt, and Pd for the CO–H2 reaction.36, 37, 38 Therefore, the reason for the high activity of Ru/Al2O3 in H2 for the desired reaction should be that the dehydrogenation and decarbonylation from pyroglutaminol formed the bridge‐type CO on Ru, and the Ru species catalyzed the hydrogenation of CO into CH4, which was readily desorbed from the surface to regenerate the active site. Similar mechanisms have been reported in reactions such as tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol to tetrahydrofuran, l‐valine to isobutylamine, and levulinic acid to 2‐butanol.39, 40, 41, 42 These reactions were reported to form CH4 from CO, just like the reaction in our study.

According to the IR measurements and pyroglutaminol conversion tests, a possible reaction pathway is hypothesized in Scheme 2. Pyroglutaminol was converted into 5‐oxoprolinal through dehydrogenation. 5‐Oxoprolinal, however, was reactive for decarbonylation and has a short lifetime, making it impossible to detect in the analysis of the reaction solution. Then, 2‐pyrrolidone and CO were formed. CO on Ru was then rapidly hydrogenated into CH4. In the conversion of pyroglutaminol, Ru/Al2O3 adsorbed the bridge‐type CO molecules, catalyzed the hydrogenation of CO into CH4, and recovered the active sites after desorption of CH4. In contrast, Pt adsorbed linear‐type CO, and Pd and Rh did not catalyze even the decarbonylation. It was previously reported that the adsorption energy of CO on metals is stronger than that of H2,43, 44 and CO hydrogenation requires the dissociation of CO.45 Therefore, the linear‐type CO adsorbed on Pt was less active for the hydrogenation into CH4 than the bridge‐type CO adsorbed on Ru. Consequently, the CO adsorbed on Pt remained, poisoning the active sites for pyroglutaminol conversion. Consequently, Ru/Al2O3 smoothly catalyzed the carbonylation of 5‐oxoprolinal, and the adsorbed CO on Ru was much more active in the hydrogenation than that on the other catalysts. Therefore, the Ru catalyst without poisoning exhibited higher activity in pyroglutaminol conversion.

Scheme 2.

Reaction pathway for pyroglutaminol conversion.

Also, Ru/Al2O3 exhibited a far higher yield of 2‐pyrrolidone in the conversion of pyroglutamic acid than the other catalysts. Probably, Pt, Pd, and Rh were less suitable to catalyze the hydrogenation of pyroglutamic acid and/or poisoned by the formed CO in the step of pyroglutaminol conversion into 2‐pyrrolidone. CO and the carbonyl groups in 5‐oxoprolinal and pyroglutamic acid are considered to be less reactive over Pt, Pd, and Rh. Therefore, the catalysts were inactive. XPS profiles of Rh and Pd indicated the oxides remain in these catalysts, and the possibility that the oxides deactivated the active sites of these catalysts cannot be ruled out. In contrast, the hydrogenation of pyroglutamic acid over Ru/Al2O3 proceeded smoothly, and the active sites were not poisoned by CO. Therefore, the 2‐pyrrolidone productivity over Ru in the conversion of pyroglutamic acid was superior to those of Pt‐, Pd‐, and Rh‐loaded catalysts, as found in the direct reaction of pyroglutaminol. The proposed reaction pathway is highly related to decarbonylation and CO hydrogenation, compared with hydrogenation and dehydrogenation.

Ru/Al2O3 exhibited 60 % 2‐pyrrolidone yield under appropriate reaction conditions of 2 h at 433 K in 2 MPa of H2, and stable activity after five runs. Also, glutamic acid was converted into 2‐pyrrolidone over Ru/Al2O3, just like pyroglutamic acid. The results suggested that the dehydration of glutamic acid into pyroglutamic acid occurred at a high reaction rate, and thus the difference between the reactants did not influence the yield of 2‐pyrrolidone.

Up to this stage, the maximum yield of 2‐pyrrolidone was approximately 60 % in the conversion of glutamic acid. Therefore, the yield should be improved. We have briefly investigated the influence of the support of the Ru catalyst on the activity. In some cases, the activity was enhanced, but the reason has not been clarified. It is speculated that the support influenced the electronic state of Ru or the adsorbed state of the reactants on the surface. In future work, the effects of the supports and Ru loading will be studied to improve 2‐pyrrolidone productivity.

Conclusions

Efficient one‐pot conversion of glutamic acid, which is an abundant nitrogen‐containing compound, into 2‐pyrrolidone was realized by a supported Ru catalyst under pressurized H2. We studied the reactions by using pyroglutaminol, pyroglutamic acid, and glutamic acid as reactants. In the conversion of pyroglutaminol, Ru/Al2O3 exhibited an extremely high activity compared with supported Pt, Pd, and Rh catalysts. IR measurements of the adsorbed species formed from pyroglutaminol on the catalysts with heating revealed that CO was formed from pyroglutaminol, and Ru rapidly converted it into CH4. As a result, the active sites on Ru were available in the conversion of pyroglutaminol. The conversion of pyroglutamic acid was also effectively catalyzed by the Ru catalyst compared with other tested catalysts. The durability of the Ru catalyst after five runs was demonstrated. In the conversion of glutamic acid, Ru/Al2O3 showed a high yield of 2‐pyrrolidone comparable to the conversion of pyroglutamic acid. The characteristics of Ru/Al2O3 are beneficial to the conversion of various amino acids into valuable nitrogen‐containing chemicals through one‐pot conversion under mild reaction conditions, which avoid the degradation of unstable amino acids above 473 K.

Experimental Section

Preparation of supported noble‐metal catalysts

Noble‐metal catalysts loaded on Al2O3 (metal loading: 5 wt %) were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. The catalysts were treated at 673 K for 3 h in H2 flow to obtain Ru/Al2O3, Pt/Al2O3, Rh/Al2O3, and Pd/Al2O3; this step is essential to stabilize the noble metals before reactions under high‐pressure hydrogen atmosphere.

Physicochemical characterization

The crystalline phases of the catalysts were analyzed by XRD (Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer) with CuKα radiation in the 2θ range from 10 to 80°. XPS (ULVAC‐PHI PHI5000 VersaProbe II) was operated with AlKα radiation (1486.6 eV). Charging effects on the Ru, Pd, and Rh catalysts were corrected by using the Al 2p peak (74.6 eV) of the Al2O3 support, whereas that on the Pt catalyst was corrected by using the Al 2s peak (119.5 eV).46 TEM (JEOL JEM1400 Plus) was conducted at an acceleration voltage of 80.0 kV. Samples were dispersed on copper grids by using ethanol after ultrasonic pretreatment. The amounts of CO chemisorbed on the catalysts were recorded at 323 K from 0.01 to 50 kPa by using a volumetric adsorption apparatus (MicrotracBel BELSORP‐max). Prior to gas adsorption, the samples were heated at 573 K in O2 and then H2 flow, and evacuated with cooling to 323 K.

Catalytic reactions

Catalytic activities for the reaction of pyroglutaminol [(S)‐5‐(hydroxymethyl)‐2‐pyrrolidinone, Tokyo Chemical Industry], l‐pyroglutamic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry), and l‐glutamic acid (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) were measured by using the reactants as received. In a typical reaction run, an aqueous solution of a reactant (0.026 mol L−1, 50 mL) and a catalyst (0.2 g) was charged into a batch autoclave reactor (120 mL, Taiatsu Techno). After sealing, the interior atmosphere was purged and pressurized to the desired pressure by using H2 or N2. The solution was stirred at 500 rpm and heated at the desired reaction temperature. After the reaction, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature. The catalyst was separated from the solution by centrifugation. The resulting solution, mixed with tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (Tokyo Chemical Industry) as an internal standard, was analyzed by using a gas chromatograph (GC‐2014, Shimadzu) with a capillary column (HP‐INNOWax) and a flame ionization detector (FID). The interior gas in the autoclave reactor was collected in a sampling bag made from aluminum and analyzed by GC (GC‐2014, Shimadzu) equipped with parallel branched columns of activated carbon and molecular sieves (WG‐100) and thermal conductivity detectors (TCD).

Conversion was calculated according to Equation (1):

| (1) |

Yields of products were calculated according to Equation (2):

| (2) |

“Others” indicates products undetected by GC, and the yield of others was calculated according to Equation (3):

| (3) |

The initial reaction rates for 2‐pyrrolidone formation over the catalysts were calculated through the amount of formed 2‐pyrrolidone for the first 1 h divided by the weight of catalyst. The TOF was calculated by normalizing the initial rate for 2‐pyrrolidone formation with the number of accessible metal atoms, which was determined by CO adsorption.

The durability of the Ru/Al2O3 catalyst was examined in five consecutive batch runs for the catalytic conversion of pyroglutamic acid at 433 K in 2 MPa H2 for 2 h. After a reaction run, the used catalyst was centrifuged and washed with deionized water (50 mL) three times. The thus recovered catalyst was dried at 383 K for 12 h and put into a new reactant mixture for the next run.

IR measurements of species formed from pyroglutaminol on catalysts

A metal‐loaded catalyst (0.2 g) was immersed in an aqueous solution of pyroglutaminol (0.026 mol L−1, 50 mL) and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. After this step for the adsorption of pyroglutaminol, the solid was separated from the resulting solution by filtration and washed with deionized water three times before it was finally dried at 383 K overnight. The IR analysis of species adsorbed on the catalyst samples was performed by using an IR spectrometer (FT/IR‐4200, JASCO). The catalyst powder was compressed at 20 MPa into a self‐supporting disk with a diameter of 1 cm and then set in the in situ IR cell (MicrotracBel IRMS‐TPD). The spectra were recorded in Ar or H2 (6 %)/Ar flow (50 mL min−1) with heating the sample at a ramp rate of 2 K min−1 up to 498 K at 4.1 kPa.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K14261.

S. Suganuma, A. Otani, S. Joka, H. Asako, R. Takagi, E. Tsuji, N. Katada, ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1381.

References

- 1. Davis S. E., Ide M. S., Davis R. J., Green Chem. 2013, 15, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kobayashi H., Fukuoka A., Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1740–1763. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Besson M., Gallezot P., Pinel C., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1827–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gilkey M. J., Xu B., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1420–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li X., Jia P., Wang T., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7621–7640. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanders J., Scott E., Weusthuis R., Mooibroek H., Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott E., Peter F., Sanders J., Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 751–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Claes L., Matthessen R., Rombouts I., Stassen I., Baerdemaeker T. D., Depla D., Delcour J. A., Lagrain B., De Vos D. E., ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamura M., Tamura R., Takeda Y., Nakagawa Y., Tomishige K., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3097–3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spiehs M. J., Whitney M. H., Shurson G. C., J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 2639–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belyea R. L., Rausch K. D., Tumbleson M. E., Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 94, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim Y., Mosier N. S., Hendrickson R., Ezeji T., Blaschek H., Dien B., Cotta M., Dale B., Ladisch M. R., Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5165–5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lammens T. M., Franssen M. C. R., Scott E. L., Sanders J. P. M., Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 44, 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sustainability in the Chemical Industry: Grand Challenges and Research Needs, 1st ed., National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2006, pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lammens T. M., Biase D. D., Franssen M. C. R., Scott E. L., Sanders J. P. M., Green Chem. 2009, 11, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lammens T. M., Le Nôtre J., Franssen M. C. R., Scott E. L., Sanders J. P. M., ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Le Nôtre J., Scott E. L., Franssen M. C. R., Sanders J. P. M., Green Chem. 2011, 13, 807–809. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teng Y., Scott E. L., Sanders J. P. M., J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deng J., Zhang Q.-G., Pan T., Xu Q., Guo Q.-X., Fu Y., RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 27541–27544. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holladay J. E., Werpy T. A., Muzatko D. S., Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2004, 115, 0857–0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Schouwer F., Claes L., Claes N., Bals S., Degrève J., De Vos D. E., Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamano N., Kawasaki N., Takeda S., Nakayama A., J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 528–533. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park S. J., Kim E. Y., Noh W., Oh Y. H., Kim H. Y., Song B. K., Cho K. M., Hong S. H., Lee S. H., Jegal J., Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hashimoto K., Hamano T., Okada M., J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 54, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lammens T. M., Franssen M. C. R., Scott E. L., Sanders J. P. M., Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morgan D. J., Surf. Interface Anal. 2015, 47, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schön G., J. Electron Spectrosc. 1972. –1973, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tura J. M., Regull P., Victori L., De Castellar M. D., Surf. Interface Anal. 1988, 11, 447–449. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fierro J. L. G., Palacios J. M., Tomas F., Surf. Interface Anal. 1988, 13, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meng M., Stievano L., Lambert J.-F., Langmuir 2004, 20, 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fujimoto K., Kameyama M., Kunugi T., J. Catal. 1980, 61, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scirè S., Crisafulli C., Maggiore R., Minicò S., Galvagno S., Catal. Lett. 1998, 51, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim M., Sim W-.S., King D. A., J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1996, 92, 4781–4785. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoshida H., Narisawa S., Fujita S., Ruixia L., Arai M., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 4724–4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Henderson M. A., Worley S. D., Surf. Sci. 1985, 149, L1–L6. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McKee D. W., J. Catal. 1967, 8, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vannice M. A., J. Catal. 1975, 37, 462–473. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vannice M. A., J. Catal. 1975, 37, 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lukes R. M., Wilson C. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 4790–4794. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bagnall W. H., Goodings E. P., Wilson C. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 4794–4798. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verduyckt J., Coeck R., De Vos D. E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3290–3295. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mizugaki T., Togo K., Maeno Z., Mitsudome T., Jitsukawa K., Kaneda K., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bond G. C., Catalysis by Metals, Academic Press, London, 1962, pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guerrero-Ruiz A., React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 1993, 49, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kellner C. S., Bell A. T., J. Catal. 1981, 70, 418–432. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hess A., Kemnitz E., Lippitz A., Unger W. E. S., Mentz D.-H., J. Catal. 1994, 148, 270–280. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary