Summary

Herein we demonstrate the successful application of reductive strategy in the asymmetric domino ring opening/cross-coupling reaction of prochiral cyclobutanones. Under the catalysis of a chiral nickel complex, various aryl iodide-tethered cyclobutanones were reacted with alkyl bromides as the electrophilic coupling partner, providing a variety of chiral indanones bearing a quaternary stereogenic center in highly enantioselective manner, which can be further converted to diverse benzene-fused cyclic compounds including indane, indene, dihydrocoumarin, and dihydroquinolinone. The preliminary mechanistic investigations support a mechanism involving Ni(I)-mediated enantiotopic C−C σ-bond activation of cyclobutanones as key elementary step in the catalytic cycle.

Subject Areas: Catalysis, Organic Synthesis, Organic Reaction

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Asymmetric ring opening of prochiralcyclobutanones via reductive Nickel-catalysis

-

•

Merger of electrophilic ring opening and cross-electrophile coupling

-

•

Chiral indanones were synthesized in highly enantioselective manner

Catalysis; Organic Synthesis; Organic Reaction

Introduction

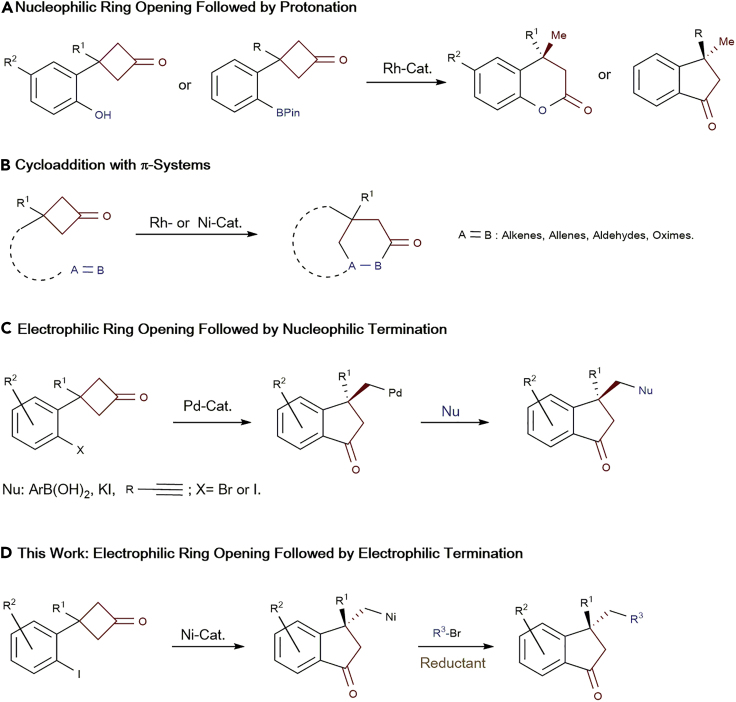

Enantioselective ring opening of small strained molecules is one of the cornerstone reactions in organic synthesis, providing a convenient access to diverse chiral compounds. However, the main progresses in this domain are limited to small heterocyles, eg, epoxides and aziridines (Jacobsen, 2000, Meninno and Lattanzi, 2016, Pastor and Yus, 2005, Schneider, 2006, Wang et al., 2016a, Wang et al., 2016b). Furthermore, significant advances have been made in the Ti-mediated radical-type regiodivergent ring opening of epoxides in recent years (Funken et al., 2016, Funken et al., 2017, Mühlhaus et al., 2019). In contrast, the development of asymmetric ring opening of small carbocycles (Schneider et al., 2014, Grover et al., 2015, Fumagalli et al., 2017) lags behind due to the challenging C-C σ-bond cleavage (Dong, 2014, Marek et al., 2015, Souillart and Cramer, 2015, Nairoukh et al., 2017). Cyclobutanones have proved to be versatile precursors for ring opening or ring expansion reaction involving C-C σ-bond activation (Murakami et al., 1994, Murakami et al., 2002, Murakami et al., 2005a, Murakami et al., 2005b, Matsuda et al., 2008, Xu and Dong, 2012, Ishida et al., 2012, Ishida et al., 2014, Ko and Dong, 2014, Chen et al., 2014, Zhou and Dong, 2015, Juliá-Hernández et al., 2015), but only a few transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric variants were reported in the last two decades, which are constrained to the following three strategies (Sietmann and Wiest, 2019): (1) In the pioneering work of Murakami, a method with an Rh-promoted enantioselectivenucleophilic ring opening of prochiralcyclobutanones as key step followed by protonation was accomplished, in which a tethered aryl boronate or phenol can serve as the nucleophile (Scheme 1A) (Matsuda et al., 2006, Matsuda et al., 2007); (2) Dong, Cramer, and Murakami developed a variety of Rh- or Ni-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular cycloadditions of cyclobutanones with various pendant unsaturated units, such as alkenes (Liu et al., 2012, Xu et al., 2012, Souillart et al., 2014, Deng et al., 2019), allenes (Zhou and Dong, 2016), aldehydes (Souillart and Cramer, 2014, Parker and Cramer, 2014), and oximes (Deng et al., 2016), affording an array of bridged bicyclic compounds with high enantiocontrol (Scheme 1B); (3) Cao, Xu, and coworkers achieved Pd-catalyzed enantioselective electrophilic ring opening of cyclobutanones with the appended aryl halide, and the resultant chiral alkyl Pd(II) species containing an indanone scaffold can be successfully trapped by different nucleophiles including aryl boronic acids, iodide, and alkynes (Scheme 1C) (Cao et al., 2019, Sun et al., 2019a, Sun et al., 2019b). Moreover, metallic Lewis-acid- or organo-catalyzed asymmetric Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of prochiral cyclobutanones has also been established by Bolm (Bolm and Beckmann, 2000), Imada (Murahashi et al., 2002), Feng (Zhou et al., 2012), and Miller (Featherston et al., 2019). To expand the scope of asymmetric ring opening of cyclobutanones, a conceptionally new reaction pathway is still highly desired.

Scheme 1.

Strategies for Enantioselective Ring Opening of Cyclobutanones

(A) Nucleophilic Ring Opening Followed by Protonation.

(B) Cycloaddition with π-Systems.

(C) Electrophilic Ring Opening Followed by Nucleophilic Termination.

(D) Electrophilic Ring Opening Followed by Electrophilic Termination.

On the other side, Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-electrophile coupling has emerged as a powerful tool for step-economical C-C bond formation with high functionality tolerance through bypassing the use of organometallics as the coupling partner (Everson and Weix, 2014, Gu et al., 2015, Moragas et al., 2014, Richmond and Moran, 2018, Wang et al., 2016a, Wang et al., 2016b, Weix, 2015). Herein we envisaged a Ni-catalyzed cascade consisting of enantioselective electrophilic ring opening of aryl-iodide-tethered cyclobutanones and the following termination of the generated alkyl Ni intermediate using electrophilic alkyl bromides via reductive strategy, providing a new entry to chiral indanones in asymmetric fashion, which is featured as a characteristic motif in numerous compounds of pharmaceutical interest (DeSolms et al., 1978, Li et al., 1995, Inoue et al., 1996, Ito et al., 2004, Huang et al., 2012, Peauger et al., 2017) (Scheme 1D).

Results and Discussion

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions

For optimization of the reaction conditions, we chose the prochiral cyclobutanone1a incorporating an aryl iodide unit and n-octyl bromide (2a) as model substrates (Table 1). Initially, various types of chiral ligands including BOX, Pyrox, PHOX, BINAP, DIOP, DuPhos, phosphoamidates etc. were investigated in this Ni-catalyzed reaction. However, all these reactions failed to deliver the desired product. To our delight, the reaction employing the Trost ligand L1 with chiral 1,2-cyclohexanediamine scaffold provided a promising result in terms of both efficiency and enantioselectivity (entry 1). Encouraged by this result, two additional Trost ligands with different backbones (L2 and L3) were tested for our reaction, giving only inferior results (entries 2 and 3). Moreover, the Trost ligand with naphthyl as linker (L4) turned out to be unsuitable for the studied reaction (entry 4). Tuning the substitution on the phenyl ring of L1 revealed that introduction of the bulky and electron-donating tert-butyl could improve the performance of the ligand (L5) concerning both reactivity and selectivity (entry 5). In sharp contrast, the desired reaction was completely shut down when the electron-withdrawing CF3 was installed on the phenyl substituent of the phosphine ligand (L6, entry 6). Next, a brief solvent screening was undertaken (entries 7–11). In general, moderate to good results were obtained in polar solvents (entries 7–9) wherein the best outcome was achieved in the case of 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI, entry 9). In less polar solvents such as THF and MeCN, the formation of the product 3a was not observed (entries 10 and 11). Subsequently, a series of Ni-precatalysts were examined for this reaction (entries 12–16). Gratifyingly, both efficiency and asymmetric induction could be elevated to a high level when NiCl2⋅glyme was utilized (entry 16). Replacing Mn by Zn as the reducing agent gave rise to a diminished yield and enantiocontrol (entry 17). In addition, we also employed the bromo analogue of 1a as precursor in this domino ring opening/cross-coupling reaction, but the conversion of 1a was not observed in this case (entry 18).

Table 1.

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligands | Ni-Salts | Solvent | Yield (%)a | ee (%)b |

| 1 | L1 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 66 | 54 |

| 2 | L2 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 15 | 13 |

| 3 | L3 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 21 | 19 |

| 4 | L4 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 0 | – |

| 5 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 69 | 76 |

| 6 | L6 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMA | 0 | – |

| 7 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMSO | 81 | 34 |

| 8 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMF | 53 | 73 |

| 9 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | DMI | 76 | 87 |

| 10 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | THF | 0 | – |

| 11 | L5 | NiBr2⋅glyme | MeCN | 0 | – |

| 12 | L5 | NiBr2 | DMI | trace | NDc |

| 13 | L5 | NiI2 | DMI | 56 | 85 |

| 14 | L5 | Ni(acac)2 | DMI | 0 | – |

| 15 | L5 | Ni(COD)2 | DMI | 73 | 89 |

| 16 | L5 | NiCl2⋅glyme | DMI | 83 | 94 |

| 17d | L5 | NiCl2⋅glyme | DMI | 23 | 70 |

| 18e | L5 | NiCl2⋅glyme | DMI | 0 | – |

Unless otherwise specified, reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale of the cyclobutanone1a using 2.0 equiv of n-octyl bromide (2a), 10 mol % Ni-precatalyst, 12 mol% ligand and 2 equiv of Mn in 1.0 mL solvent at 40 °C for 12 h.

Yields of the isolated product after column chromatography.

Determined by HPLC-analysis on chiral stationary phase.

Not determined.

Zn was used as reductant instead of Mn.

The bromo analogue of 1a was used instead of 1a.

Substrate Scope

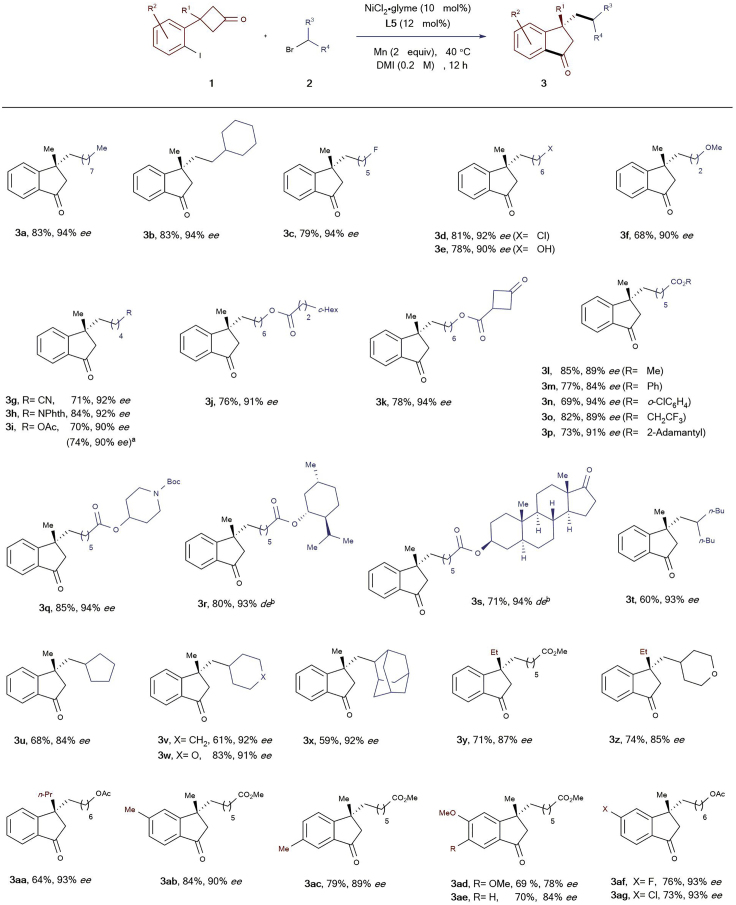

After establishing the optimal reaction conditions, we started to evaluate the substrate spectrum of this Ni-catalyzed reaction (Scheme 2). First, an array of primary alkyl bromides reacted with the cyclobutanone1a. All these reactions proceeded smoothly under the standard conditions, furnishing the product 3a-q in moderate to good yields and good to excellent enantioselectivities. It is noteworthy that a wide range of functional moieties including chloride (3d), alcohol (3e), nitrile (3g), imide (3h), ester (3i-q), ketone (3k), and carbamate (3q) were well tolerated. Furthermore, the alkyl bromides containing a menthol or epiandrosterone subunit posed no problem, providing the products 3r and 3s in good efficiency and high diastereomeric excesses. Moreover, sterically more demanding secondary alkyl bromides also turned out to be competitive substrates for this reaction, and the corresponding products 3t-x were obtained in moderate to good yields and good to high enantiocontrol. Unfortunately, no desired product was formed when tertiary alkyl and benzyl halides were employed as precursors. Next, the impact of geminal substitution on the β-position of the prochiralcyclobutanones was examined. In the case of ethyl and n-propyl substituent comparable results were achieved (3y-aa), whereas no desired reaction occurred in the case of phenyl substitution. The use of mono-substituted cyclobutanone (R1= H) as a precursor also failed to deliver the cross-coupling product. Subsequently, we continued to study the scope of this reaction through introduction of either electron-donating or withdrawing groups to the tethered phenyl ring (3ab-ag), and in all these cases the products were afforded in good yields and good to high enantiomeric excesses. Notably, a 10-mmol-scale reaction for synthesis of 3i was carried out providing a similar result.

Scheme 2.

Evaluation of the Substrate Scope

Unless otherwise specified, reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale of the cyclobutanones 1 using 2.0 equiv of alkyl bromides 2, 10 mol% NiCl2·glyme, 12 mol% ligand L5, and 2 equiv of Mn in 1.0 mL DMI at 40 ° C for 12 h. Yields of the isolated products after column chromatography. The ee or de were determined by HPLC-analysis on chiral stationary phase. dThe reaction was performed on a 10 mmol scale. eEnantiopure precursors were employed.

Derivatization of the Products

In order to demonstrate synthetic value of this method, some derivatizations of the cross-coupling product 3i were conducted (Scheme 3). First, Clemmensen reduction of the keto-moiety afforded a chiral indane 4 in an excellent yield. Compound 3i was also successfully subjected to Wittig olefination, providing a geminal disubstituted alkene 5 in a moderate yield. Moreover, the conversion of the indanone 3i into the corresponding oxime using hydroxyl amine followed by PCl5-mediated Beckmann rearrangement delivered a dihydroquinolinone 6 in 56% yield over two steps. In addition, the framework of dihydrocoumarin (7) or 3-aryl indene (8) can be constructed starting from the indanone 3i according to the known procedure in the literature (Jin and Wang, 2017).

Scheme 3.

Derivatizations of the Cross-Coupling Product

(A) Zn-Hg, 6 M HCl, toluene/H2O, RT, overnight.

(B) Ph3P+CH2Br− (1.1 equiv), t-BuOK (1.5 equiv), MeOH, 0°C to RT, overnight.

(C) NH2OH⋅HCl (1.1 equiv), NaOAc (2.0 equiv), MeOH, 60°C, 2 h.

(D) PCl5 (1.0 equiv), THF, 60°C, 1.5 h.

Mechanistic Studies

A series of control experiments were designed to uncover the mechanism of this Ni-catalyzed reaction (Scheme 4). First, we performed the stoichiometric reaction between the cyclobutanone1a and Ni(COD)2 in the presence of the ligand L5. After quenching with water, the formation of the indanone 9 was not observed, whereas the deiodinated product 10 was obtained in 89% yield (Scheme 4A). Considering that MnI2 is present in the catalytic reaction and can serve as Lewis acid to activate the carbonyl group, we performed this stoichiometric reaction with 1 equiv of MnI2. Again, only the deiodinated product 10 was generated (83% yield). This result confirms the feasibility of oxidative addition of the incorporated aryl iodide to the Ni(0) species, but the generated Ni(II) complex 11 is not able to further react with the Cyclobutanone to approach the indanone motif. When the reductant Mn (2 equiv) was added to the stoichiometric reaction mentioned earlier, the indanone 9 was furnished in 84% yield (Scheme 4B). In this case, the aryl Ni(II) intermediate 11 is probably reduced to the corresponding Ni(I) species 12, which can subsequently undergo two possible reaction pathways: (1) oxidative addition with the cyclobutanone moiety followed by facile reductive elimination from the bridged bicyclic Ni(III) species 13; (2) migratory insertion into the carbonyl moiety followed by β-carbon-elimination from the Ni(I) complex 14. In both cases, the Ni(I) intermediate 15 with the indanone scaffold could be approached, which upon protonation leads to the compound 9. Moreover, the stoichiometric reaction employing the aryl iodide 16 tethering a linear ketone failed to deliver the addition product 17, arguing against the mechanism involving a Ni(I)-mediated migratory insertion step (Scheme 4C). Next, the sequential stoichiometric reaction with the addition of n-octyl bromide (2a) in the second stage provided the coupling product 3a in 88% ee, which is similar to one of the catalytic reactions (Scheme 4D). This result suggests that the enantiotopic C-C bond activation is probably the enantiodeterming step with generation of the Ni-complex 15, which can further react with n-octyl bromide to reach the product 3a. Moreover, an alkyl bromide with a pendant olefinic unit (2z) was employed as a precursor in the Ni-catalyzed reaction with cyclobutanone1a under the standard conditions, which resulted in cyclization of the alkyl bromide prior to the cross-coupling reaction (Scheme 4E). The corresponding product 3ah was yielded in a diastereomeric ratio of 1:1, which indicates a free-radical-mediated ring closure for the formation of the cyclopentane ring.

Scheme 4.

Control Experiments

(A) Stoichiometric Reaction of 1a with Ni(COD)2.

(B) Stoichiometric Reaction of 1a with Ni(COD)2 in the Presence of Mn.

(C) Stoichiometric Reaction of 16 with Ni(COD)2.

(D) Sequential Stoichiometric Reaction.

(E) Radical Clock Experiment.

Proposed Catalytic Cycle

On the basis of the results of the control experiments, we proposed a plausible reaction mechanism for this Ni-catalyzed ring opening/cross-coupling reaction (Scheme 5). Initially, a Ni(0) species is generated under the reductive condition, which undergoes oxidative addition with the tethered aryl iodide 1. Next, the resultant Ni(II) complex I is reduced by Mn to the Ni(I) intermediate II, which in turn performs enantioselective insertion into one of the two C(sp2)-C(sp3) σ-bonds of the cyclobutanone to give the bicyclic Ni(III) complex III. The subsequent C(sp2)-C(sp2) reductive elimination affords the alkyl Ni(I) species IV with the indanone scaffold. In the next step, alkyl bromides 3 conduct oxidative addition to the complex IV via the formation of a cage V consisting of an alkyl radical and a Ni(II) species. Upon reductive elimination from the intermediate VI, the indanone products 3 are furnished. Finally, the Ni(0) species is regenerated for the next catalytic cycle via the Mn-mediated reduction of Ni(I)Br.

Scheme 5.

Proposed Reaction Mechanism

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a reductive strategy for ring opening of prochiral cyclobutanones via sequential C−C bond cleavage and electrophilic trapping. Under the catalysis of a chiral Ni-complex in assistance of Mn as reducing agent, various cyclobutanones tethering an aryl iodide were reacted with both primary and secondary alkyl bromides, furnishing a variety of chiral indanones containing a quaternary stereogenic center in good to high enantioselectivities. According to the preliminary mechanistic studies, this tandem reaction proceeds with selective insertion of Ni(I) into the C−C σ-bond of cyclobutaonones as the enantiodetermining step, and the subsequent cage-bound oxidative addition with alkyl bromides and reductive elimination can afford the ring opening/cross-coupling products.

Limitation of the Study

Tertiary alkyl and benzyl bromides are not applicable in this methodology.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21772183), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WK2060190086), “1000-Youth Talents Plan” start-up funding as well as University of Science and Technology of China.

Author Contributions

C.W. and D.D. conceived and designed the experiments. D.D. and H.D. performed experiments and prepared the Supplementary Information. C.W. directed the project and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Published: April 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101017.

Data and Code Availability

All data and methods can be found in the Supplemental Information.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bolm C., Beckmann O. Zirconium-mediated asymmetric baeyer-villiger oxidation. Chirality. 2000;12:523–525. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(2000)12:5/6<523::AID-CHIR39>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Chen L., Sun F.-N., Sun Y.-L., Jiang K.-Z., Yang K.-F., Xu Z., Xu L.-W. Pd-catalyzed enantioselective ring opening/cross-coupling and cyclopropanation of cyclobutanones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:897–901. doi: 10.1002/anie.201813071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.-h., Xu T., Dong G. Divergent syntheses of fused β-naphthol and indene scaffolds by rhodium-catalyzed direct and decarbonylative alkyne-benzocyclobutenone couplings. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:1674–1678. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Xu T., Li H., Dong G. Enantioselective Rh-catalyzed carboacylationof C=N bonds via C–C activation of benzocyclobutenones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:369–374. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Fu Y., Lee S.Y., Wang C., Liu P., Dong G. Kinetic resolution via Rh-catalyzed C–C activation of cyclobutanones at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:16260–16265. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSolms S.J., Woltersdorf O.W., Jr., Cragoe E.J., Jr., Watson L.S., Fanelli G.M., Jr. (Acylaryloxy)acetic acid diuretics. 2. (2-Alkyl-2-aryl-1-oxo-5-indanyloxy)acetic acids. J. Med. Chem. 1978;21:437–443. doi: 10.1021/jm00203a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G., editor. Top.Curr. Chem. Springer-Verlag; 2014. p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Everson D.A., Weix D.J. Cross-electrophile coupling: Principles of reactivity and selectivity. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:4793–4798. doi: 10.1021/jo500507s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherston A.L., Shugrue C.R., Mercado B.Q., Miller S.J. Asymmetric Baeyer–Villigerreaction with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by a novel planar-chiral bisflavin. ACS Catal. 2019;9:242–252. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b04132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli G., Stanton S., Bower J.-F. Recent methodologies that exploit C–C single-bond cleavage of strained ring systems by transition metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:9404–9432. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funken N., Mühlhaus F., Gansäuer A. General, highly selective synthesis of 1,3- and 1,4-difunctionalized building blocks by regiodivergent epoxide opening. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:12030–12034. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funken N., Zhang Y.-Q., Gansäuer A. Regiodivergentcatalysis: a powerful tool for selective catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:19–32. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover H.K., Emmett M.R., Kerr M.A. Carbocycles from donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:655–671. doi: 10.1039/c4ob02117g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Wang X., Xue W., Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkyl halides with other electrophiles: concept and mechanistic considerations. Org. Chem. Front. 2015;2:1411–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Lu C., Sun Y., Mao F., Luo Z., Su T., Jiang H., Shan W., Li X. Multitarget-directed benzylideneindanone derivatives: anti-β-amyloid (Aβ) aggregation, antioxidant, metal chelation, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition properties against Alzheimer’s disease. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:8483–8492. doi: 10.1021/jm300978h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A., Kawai T., Wakita M., Iimura Y., Sugimoto H., Kawakami Y. The simulated binding of (±)-2,3-dihydro-5,6-dimethoxy-2-[[1-(phenylmethyl)-4-piperidinyl]methyl]-1H-inden-1-one hydrochloride (E2020) and related inhibitors to free and acylatedacetylcholinesterases and corresponding structure-activity analyses. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4460–4470. doi: 10.1021/jm950596e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida N., Ikemoto W., Murakami M. Intramolecularσ-bond metathesis between carbon–carbon and silicon–silicon bonds. Org. Lett. 2012;14:3230–3232. doi: 10.1021/ol301280u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida N., Ikemoto W., Mukarami M. Cleavage of C–C and C–Si σ-bonds and their intramolecular exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5912–5915. doi: 10.1021/ja502601g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Tanaka T., Iinuma M., Nakaya K.-i., Takahashi Y., Sawa R., Murata J., Darnaedi D. Three new resveratrol oligomers from the stem bark of vaticapauciflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:932–937. doi: 10.1021/np030236r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen E.N. Asymmetric catalysis of epoxide ring-opening reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:421–431. doi: 10.1021/ar960061v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Wang C. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive arylalkylation of unactivated alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;58:6722–6726. doi: 10.1002/anie.201901067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliá-Hernández F., Ziadi A., Nishimura A., Martin R. Nickel-catalyzed chemo-, regio- and diastereoselective bond formation through proximal C−C cleavage of benzocyclobutenones. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:9537–9541. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H.M., Dong G. Cooperative activation of cyclobutanones and olefins leads to bridged ring systems by a catalytic [4 + 2] coupling. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.S., Black W.C., Chan C.-C., Ford-Hutchinson A.W., Gauthier J.Y., Gordon R., Guay D., Kargman S., Lau C.K., Mancini J. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.synthesis and pharmacological activities of 5-methanesulfonamido-1-indanone derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:4897–4905. doi: 10.1021/jm00025a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Ishida N., Murakami M. Atom- and step-economical pathway to chiral benzobicyclo[2.2.2]octenones through carbon-carbon bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:2485–2488. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek I., Masarwa A., Delaye P.-O., Leibeling M. Selective carbon–carbon bond cleavage for the stereoselective synthesis of acyclic systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:414–429. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., Shigeno M., Murakami M. Enantioselective C−C bond cleavage creating chiral quaternary carbon centers. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3379–3381. doi: 10.1021/ol061359g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., Shigeno M., Murakami M. Asymmetric synthesis of 3,4-dihydrocoumarins by rhodium-catalyzed reaction of 3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)cyclobutanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12086–12087. doi: 10.1021/ja075141g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., Shigeno M., Murakami M. Palladium-catalyzed sequential carbon−carbon bond cleavage/formation producing arylatedbenzolactones. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5219–5222. doi: 10.1021/ol802218a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meninno S., Lattanzi A. Organocatalyticasymmetric reactions of epoxides: recent progress. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22:3632–3642. doi: 10.1002/chem.201504226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moragas T., Correa A., Martin R. Metal-catalyzed reductive coupling reactions of organic halides with carbonyl-type compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:8242–8258. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlhaus F., Weiβbarth H., Dahmen T., Schnakenburg G., Gansäuer A. Merging regiodivergent catalysis with atom-economical radical arylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:14208–14212. doi: 10.1002/anie.201908860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murahashi S.-I., Ono S., Imada Y. Asymmetric baeyer–villigerreaction with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by a novel planar-chiral bisflavin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2366–2368. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020703)41:13<2366::AID-ANIE2366>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Amii H., Ito Y. Selective activation of carbon-carbon bonds next to a carbonylgroup. Nature. 1994;370:540–541. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Itahashi T., Ito Y. Catalyzed intramolecular olefin insertion into a carbon−carbon single bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13976–13977. doi: 10.1021/ja021062n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Kadowaki S., Fujimoto A., Ishibashi M., Matsuda T. Acids direct 2-styrylcyclobutanone into two distinctly different reaction pathways. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2059–2061. doi: 10.1021/ol0506922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Ashida S., Matsuda T. Nickel-catalyzed intermolecular alkyne insertion into cyclobutanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6932–6933. doi: 10.1021/ja050674f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairoukh Z., Cormier M., Marek I. Merging C–H and C–C bond cleavage in organic synthesis. Nat. Chem. Rev. 2017;1:35. [Google Scholar]

- Parker E., Cramer N. Asymmetric rhodium(I)-catalyzed C–C activations with zwitterionicbis-phospholane ligands. Organometallics. 2014;33:780–787. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M.I., Yus M. Asymmetric ring opening of epoxides. Curr.Org. Chem. 2005;9:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Peauger L., Azzouz R., Gembus V., Ţînţaş M.-L., Santos J.S.O., Bohn P., Papamicaël C., Levacher V. Donepezil-based central acetylcholinesterase inhibitors by means of a “bio-oxidizable”prodrug strategy: design, synthesis, and in vitro biological evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:5909–5926. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond E., Moran J. Recent advances in nickel catalysis enabled by stoichiometric metallic reducing agents. Synthesis. 2018;50:499–513. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. Synthesis of 1,2-difunctionalized fine chemicals through catalytic, enantioselective ring-opening reactions of epoxides. Synthesis. 2006;38:3919–3944. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T.F., Kaschel J., Werz D.B. A new golden age for donor–acceptor cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:5504–5523. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sietmann J., Wiest J.M. Enantioselectivedesymmetrization of cyclobutanones: a speedway to molecular complexity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58 doi: 10.1002/anie.201910767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souillart L., Cramer N. Highly enantioselectiverhodium(I)-catalyzed carbonyl carboacylations initiated by C−C bond activation. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9640–9644. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souillart L., Cramer N. Catalytic C–C bond activations via oxidative addition to transition metals. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:9410–9464. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souillart L., Parker E., Cramer N. Highly enantioselectiverhodium(I)-catalyzed activation of enantiotopiccyclobutanoneC−C bonds. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3001–3005. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-L., Wang X.-B., Sun F.-N., Chen Q.-Q., Cao J., Xu Z., Xu L.-W. Enantioselectivecross-exchange between C−I and C−C σ bonds. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:6747–6751. doi: 10.1002/anie.201902029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F.-N., Yang W.-C., Chen X.-B., Sun Y.-L., Cao J., Xu Z., Xu L.-W. Enantioselectivepalladium/copper-catalyzed C–C σ-bond activation synergized with sonogashira-type C(sp3)–C(sp) cross-coupling alkynylation. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:7579–7583. doi: 10.1039/c9sc02431j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Luo L., Yamamoto H. Metal-catalyzed directed regio- and enantioselective ring-opening of epoxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:193–204. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Dai Y., Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive couplings. Top.Curr. Chem. 2016;374:43. doi: 10.1007/s41061-016-0042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weix D.J. Methods and mechanisms for cross-electrophile coupling of Csp2 halides with alkyl electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1767–1775. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Dong G. Rhodium-catalyzed regioselectivecarboacylation of olefins: a C−C bond activation approach for accessing fused-ring systems. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7567–7571. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Ko H.M., Savage N.A., Dong G. Highly enantioselectiverh-catalyzed carboacylation of olefins: efficient syntheses of chiral poly-fused rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:20005–20008. doi: 10.1021/ja309978c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Dong G. (4+1) vs (4+2): catalytic intramolecular coupling between cyclobutanones and trisubstitutedallenesvia C–C activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:13715–13721. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Dong G. Nickel-catalyzed chemo- and enantioselective coupling between cyclobutanones and allenes: rapid synthesis of [3.2.2] bicycles. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:15091–15095. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Liu X., Li J., Zhang Y., Hu X., Lin L., Feng X. Kinetic resolution via Rh-catalyzed C–C activation of cyclobutanones at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17023–17026. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and methods can be found in the Supplemental Information.