Summary

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of gender on outcomes among adult burn patients. A retrospective study was conducted on 5061 adult burn patients (16 - 64 years old) admitted to the Vietnam National Burn Hospital over a three-year period (2016 - 2018). Demographic data, burn features and outcome including complications, length of hospital stay and mortality of male and female groups were compared. Results indicated that male patients were predominant (72.8%), younger (35.5 vs. 37.2 years old; p < .001) and admitted sooner to hospital. A greater number of males suffered electrical and flame/heat direct contact injuries, whereas more females suffered scald injury (34.7% vs. 12.2%; p < .001). Burn extent was larger among males (14.9% vs. 12.1%; p < .001). In addition, a higher proportion of deep burn injuries (44.8% vs. 41.2%; p < .05) and number of surgeries (1.2 vs. 1; p < .05), and longer hospital stay (17.8 vs. 15.8 days; p < .001) was recorded among the male group. Post burn complication and overall mortality rate did not differ between the two groups. However, death rate was remarkably higher in the female group when burn extent was ≥ 50% TBSA (72.4% vs. 57.3%; p < .05). In conclusion, burn features and outcomes were not similar between the male and female group. Male patients appear to suffer more severe injury requiring more surgeries and longer hospital stay. However, more attention should be paid to the significantly higher mortality rate among females with extensive burn.

Keywords: burn, gender, outcomes

Abstract

Le but de ce travail était d’étudier l’impact du sexe sur le devenir d’adultes brûlés. Cette étude rétrospective a été conduite sur 5 601 patients âgés de 16 à 64 ans admis dans le CTB national du Vietnam entre 2016 et 2018 inclus. Les données démographiques, celles concernant la brûlure, les complications, la durée d’hospitalisation et la mortalité ont été comparées selon le sexe des patients. Les hommes prédominent (72,8%), sont plus jeunes (35,5 VS 37,2 ans - p<0,001) et sont hospitalisés plus rapidement. Les ébouillantements sont plus fréquents chez les femmes (34,7 VS 12,2% - p <0,001), les autres causes (électriques, flammes, contact) étant donc plus habituelles chez les hommes. Les brûlures des hommes sont plus étendues (14,9 VS 12,1% SCB - p< 0,001), plus profondes (44,8% de profond VS 41,2% - p< 0,05 ; 1,2 séances chirurgicales VS 1 - p< 0,05) et leur durée de séjour est plus longue (17,8 VS 15,8 j - p< 0,001). Le nombre de complications et la mortalité sont comparables. Toutefois, la mortalité des femmes brûlées sur ≥ 50% SCT était nettement plus élevée que celle des hommes (72,4% VS 57,3% - p< 0,05). En conclusion, les hommes ont des brûlures plus sévères nécessitant plus d’interventions chirurgicales et une hospitalisation plus longue. Il faut cependant être attentifs à la mortalité élevée des femmes extensivement brûlées.

Introduction

The impact of gender difference on outcomes of hospitalized patients has been a recent topic of interest. Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated a lower mortality rate for female patients compared to males. This pattern has been observed for most causes of death, from chronic disease, sepsis and hemorrhage.1,2,3,4 However, there is still signifi cant controversy over gender differences and outcomes of trauma patients, including burn patients.5,6,7 Despite advances in resuscitation, early enteral nutrition, hypermetabolic modulation and surgical management, burn patient mortality is still high, especially in developing countries.8,9 To date, age, burn extent and inhalation injury have been considered to be independent predictive factors affecting the survival rate of burn patients.10,11,12 The features and infl uence of gender on burn outcomes have also received attention recently. To date, few studies have reported about the impact of gender in adult patients in developing countries. The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine characteristics and the association between gender and outcomes in adult burn patients treated at the National Burn Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Materials and methods

We conducted a retrospective study of all adult patients (16 to 64 years old) admitted to the National Burn Hospital over a period of three years (1/1/2016 - 31/12/2018). Patients were classifi ed into a female and male group. Demographic parameters including age, gender, pre-existing medical conditions, time of admission after burn accident, season and casual agents were collected. Burn features including burn extent, deep burn injury, deep burn area and inhalation injury were also recorded. Outcome measures included complication, length of stay in hospital, number of surgeries and mortality rate. Data were analyzed and compared using Intercooled Stata version 11.0 software, and p < .05 was considered a signifi cant level. The study was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee.

Results

Of the 5061 adult patients admitted to our hospital over the three years, 3683 were male, accounting for 72.8%. Male patients were younger compared to female patients (35.5 vs. 37.2 years old; p < .001). A signifi cantly higher proportion of female patients lived in an urban area (37.2% vs. 31.8%; p < .001) compared to males. It is noteworthy that 42.7% of female patients were admitted to hospital 24h after burn injury compared to 34% in the male group (p < .001). In addition, more males suffered electrical and fl ame/heat surface contact injuries than females (p < .001), whereas more females suffered scald injury (34.7% vs. 12.2%; p < .001). There were no signifi cant differences between the two groups regarding season of burn injury and pre-existing medical conditions (Table I).

Table I. Patient characteristics (n=5061).

Distribution of gender and burn parameters is indicated in Table II. Burn extent was signifi cantly larger in the male group (14.9% vs. 12.1%; p < .001). A total of 568 (41.2%) female patients suffered full thickness burn injury compared to 1648 (44.8%) male patients (p = .024). Average deep burn area and incidence of inhalation injury were similar between the two groups (p > .05).

Table II. Distribution of burn features by gender.

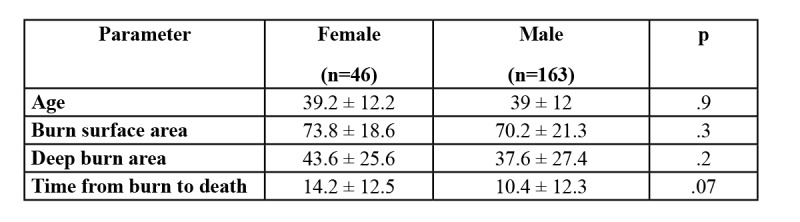

Bivariate analysis of gender and outcomes indicated a signifi cantly higher number of surgeries (1.2 vs. 1; p < .01) and longer hospital stay (17.8 vs. 15.8 days; p < .001) in the male group. Post burn complication and overall mortality rate were not remarkably different between the two groups. In addition, death rate was not signifi cantly different between the two groups where deep burn area was ≥ 20% TBSA, inhalation injury was present or patient age was ≥ 50 years old. However, death rate was remarkably higher in female patients with a burn extent ≥ 50% TBSA (72.4% vs. 57.3%; p < .05) (Table III). Data in Table IV indicate that the age of patients who died was similar for both groups (around 39 years old). In addition, average burn extent and deep burn area were higher in the female group: time from burn occurrence to death was also longer in the female group but none of the differences reached signifi cant level (p > .05).

Table III. Relationship between gender and outcomes.

Table IV. Distribution of parameters by gender among patients who died.

Discussion

The impact of gender on health outcomes is currently a focus of attention. Around the world, life expectancy is reported to be lower for males. In addition, men seem to suffer more cardiovascular diseases and hypertension, and less inflammatory or metabolic-related diseases.1 Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated a higher mortality rate among males following trauma compared to females.13,14,15,16 In China, a retrospective data analysis of 1789 blunt trauma patients demonstrated that females were more likely to survive and to have less complications than men.2 In a multi-centre study, Wohltmann and colleagues found increased mortality in male patients aged 50 years or younger compared to females. 6 The same result was reported by Morris et al. for male patients with an Injury Severity Score of 9 to 15 and age over 40 years, compared to women.7 However, other studies have reported conflicting results. In 2002, Gannon et al. conducted a prospective analysis of the data of 22,332 trauma patients treated in 26 trauma centers, and concluded that there was no association between females and lower mortality (OR 0.83, CI 0.67 to 1.03, p = 0.093).17 In 2019 Tounsi et al. analyzed injury features and outcomes in terms of surgery and mortality in Afghanistan. They showed that females accounted for 23.6% of patients, arrived later, had different injury patterns, required fewer surgeries than men and had lower unadjusted odds for mortality, although this was not significant in the adjusted analysis (OR 0.81, CI 0.446–1.453), compared to males.18 Conflicting clinical reports regarding the impact of gender on survival after trauma, sepsis and critical illness may in part be due to different study designs, sample size, or failure to adequately control for additional factors contributing to the development of sepsis and mortality.19,20,21 In addition, animal studies demonstrate that the sex hormones influence inflammatory response to injury. These results may highlight the importance of sex hormones in traumatic injury outcomes. Various experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of estrogen for the central nervous system, the cardiopulmonary system, the liver, the kidneys, the immune system, and for the overall survival of the host.22,23,24 Therefore use of hormone replacement therapy should be encountered in studies on gender differences.

Some retrospective clinical studies have focused on gender differences and the influence of gender on outcome following burn injuries. All reports indicated a lower proportion of injuries, smaller burn extent and higher incidence of scald burn in women compared to men. For example, a study by Karimi et al. on 334 adult patients with >20% TBSA indicated that female patients accounted for 18%, with smaller burn size.25 McGwin and colleagues showed that female burn patients were more likely to be older and more likely to suffer flame and scald burns.26 In the report by Kobayashi et al., 37% of the patients were female.27 In our study, women accounted for 27.2% of cases, were younger, and had a higher rate of scald burns and smaller burn extent compared to men. Regarding hospitalization, Mohammadi et al. reported that length of hospital stay was significantly higher for the female group than for the male group.28 In our study, longer stay in hospital (17.8 vs. 15.8 days; p < .001) was recorded among the males as a result of a higher rate of deep burn, larger burn extent and a greater number of surgeries required.

It is interesting to note that, unlike in the case of non-thermal patients, the mortality rate for female burn patients was mostly higher than that for men of the same age. A report by McGwin et al. indicated that among burn patients up to the age of 60, female mortality rate was more than double that of males (OR = 2.3) with similar causes and timing of death.26 O’Keefe et al. reviewed the data of 4927 patients admitted to the Parkland Memorial Hospital Burn Unit and found that the risk of death was about two-fold higher in women aged 30 to 59 years than in men of the same age.29 Kerby et al. reported that female burn patients had a 30% increased risk of dying compared to men.30 The same result has been reported by other authors.31,32 Regarding time to death, our results showed that male patients seem to die sooner than females (10.4 vs. 14.2 days after burn) although this result was not significant. This is opposed to a report by Karimi et al. (day 4 vs. day 10 post injury).25

It is noted that, as in the case of non-thermal patients, conflicting results have been reported among burn patients. For example, Kobayashi et al. reported that gender was not a risk factor for high mortality in any age group.27 In our study, death rate was remarkably higher in the female group only in cases of burn extent ≥ 50% TBSA (72.4% vs. 57.3%; p < .05). The difference in results could be explained by different sample size, time of study, criteria for selecting patients and/or other confounding factors. In this study, we did not find a significant association of age (≥ 50 years) and mortality rate between the two groups. A limitation that characterizes other previous retrospective studies is that we did not have any information on the use of hormone replacement therapy among female patients. In the future, a prospective study including information on hormone replacement therapy should be conducted to find a true association between gender difference and burn outcome.

Conclusion

We have shown that burn features and outcomes are not similar for male and female groups. Compared to males, females represent a lower proportion of burn patients, have less severe injuries, undergo fewer surgeries and have a shorter stay in hospital. However, mortality rate for females with extensive burn was significantly higher.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement.We are grateful to staff at the National Burns Hospital for helping us to collect the data.

References

- 1.Crimmins EM, Shim H, Zhang YS, Kim JK. Differences between men and women in mortality and the health dimensions of the morbidity process. Clin Chem. 2019;65(1):135–145. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.288332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Z, Shang X, Qi P, Ma S. Sex-based differences in outcomes after severe injury: an analysis of blunt trauma patients in China. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0389-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietropaoli AP, Glance LG, Oakes D, Fisher SG. Gender differences in mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Gend Med. 2010;7(5):422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder J, Kahlke V, Staubach KH, Zabel P, Stuber F. Gender differences in human sepsis. Arch Surg. 1998;133(11):1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bösch F, Angele MK, Chaudry IH. Gender differences in trauma, shock and sepsis. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40779-018-0182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohltmann CD, Franklin GA, Boaz PW. A multicenter evaluation of whether gender dimorphism affects survival after trauma. Am J Surg. 2001;181:297–300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JA Jr, MacKenzie EJ, Damiano AM, Bass SM. Mortality in trauma patients: the interaction between host factors and severity. J Trauma. 1990;30:1476–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: Distribution and risk factors. Burns. 2011;37(7):1087–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokes MAR, Johnson WD. Burns in the Third World: an unmet need. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2017;30(4):243–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tobiasen J, Hiebert JH, Edlich RF. Prediction of burn mortality. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;154(5):711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DL, Cairns BA, Ramadan F, Dalston JS. Effect of inhalation injury, burn size, and age on mortality: a study of 1447 consecutive burn patients. J Trauma. 1994;37(4):655–659. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199410000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, Sheridan RL. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998;38(6):362–366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George RL, McGwin Jr G, Metzger J, Chaudry IH, Rue LW. The association between gender and mortality among trauma patients as modified by age. J Trauma. 2003;54(3):464–471. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000051939.95039.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George RL, McGwin Jr G, Windham ST, Melton SM. Age-related gender differential in outcome after blunt or penetrating trauma. Shock. 2003;19(1):28–32. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croce MA, Fabian TC, Miller PR, Bee TK. Impact of gender on outcome in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2001;50:183. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Napolitano LM, Greco ME, Rodriguez A, Kufera JA. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:274–280. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200102000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gannon CJ, Napolitano LM, Pasquale M, Tracy JK, McCarter JR. A statewide population-based study of gender differences in trauma: validation of a prior single-institution study. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tounsi LL, Daebes HL, Gerdin Wamberg M, Nerlander M. Association between gender, surgery and mortality for patients treated at Médecins Sans Frontières Trauma Centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan. World J Surg. 2019;43(9):2123–2130. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05015-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knudson MM, Lieberman J, Morris JA Jr, Cushing BM, Stubbs HA. Mortality factors in geriatric blunt trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1994;129:448–453. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420280126017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottochian M, Salim A, Berry C, Chan LS. Severe traumatic brain injury: is there a gender difference in mortality? Am J Surg. 2009;197(2):155–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Offner PJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL. Male gender is a risk factor for major infections after surgery. Arch Surg. 1999;134(9):935–938. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory MS, Duffner LA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Estrogen mediates the sex difference in post-burn immunosuppression. J Endocrinol. 2000;164(2):129–138. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1640129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zellweger R, Wichmann MW, Ayala A, Stein S. Females in proestrus state maintain splenic immune functions and tolerate sepsis better than males. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(1):106–110. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horton JW, White DJ, Maass DL. Gender-related differences in myocardial inflammatory and contractile responses to major burn trauma. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(1):H202–H213. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00706.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karimi K, Faraklas I, Lewis G, Ha D. Increased mortality in women: sex differences in burn outcomes. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:18. doi: 10.1186/s41038-017-0083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGwin Jr G, George RL, Cross JM, Reiff DA. Gender differences in mortality following burn injury. Shock. 2002;18(4):311–315. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi K, Ikeda H, Higuchi R, Nozaki M. Epidemiological and outcome characteristics of major burns in Tokyo. Burns. 2005;31 Suppl 1:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi AA, Pakyari MR, Jafari SMS, Tavakkolian AR. Effect of burn sites (upper and lower body parts) and gender on extensive burns’ mortality. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;40(2):166–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Keefe GE, Hunt JL, Purdue GF. An evaluation of risk factors for mortality after burn trauma and the identification of gender-dependent differences in outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;192(2):153–160. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerby JD, McGwin Jr G, George RL, Cross JA. Sex differences in mortality after burn injury: results of analysis of the National Burn Repository of the American Burn Association. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27(4)X:452–456. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000225957.01854.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bedri H, Romanowski KS, Liao J, Al-Ramahi G. A national study of the effect of race, socioeconomic status, and gender on burn outcomes. J Burn Care Res. 2007;38(3):161–168. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George RL, McGwin G Jr, Schwacha MG, Metzger J. The association between sex and mortality among burn patients as modified by age. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26(5):416–421. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000176888.44949.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]