Abstract

Spermatogonial development is a vital prerequisite for spermatogenesis and male fertility. However, the exact mechanisms underlying the behavior of spermatogonia, including spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) self-renewal and spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation, are not fully understood. Recent studies demonstrated that the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway plays a crucial role in spermatogonial development, but whether MTOR itself was also involved in any specific process of spermatogonial development remained undetermined. In this study, we specifically deleted Mtor in male germ cells of mice using Stra8-Cre and assessed its effect on the function of spermatogonia. The Mtor knockout (KO) mice exhibited an age-dependent perturbation of testicular development and progressively lost germ cells and fertility with age. These age-related phenotypes were likely caused by a delayed initiation of Mtor deletion driven by Stra8-Cre. Further examination revealed a reduction of differentiating spermatogonia in Mtor KO mice, suggesting that spermatogonial differentiation was inhibited. Spermatogonial proliferation was also impaired in Mtor KO mice, leading to a diminished spermatogonial pool and total germ cell population. Our results show that MTOR plays a pivotal role in male fertility and is required for spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation.

Keywords: male fertility, mice, Mtor, spermatogenesis, spermatogonia, testis

INTRODUCTION

Spermatogenesis is a highly intricate and coordinated process that allows continuous daily production of millions of spermatozoa throughout the reproductive lifespan of male mammals.1 This sustained production of spermatozoa depends on the development of spermatogonia, which was classified into two subpopulations, undifferentiated spermatogonia and differentiating spermatogonia.2,3 In mice and other rodents, undifferentiated spermatogonia include spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) and progenitor spermatogonia, which can be subdivided into Asingle (As), Apaired (Apr), and Aaligned (Aal) spermatogonia according to the number of cells connected by intercellular cytoplasmic bridges. Differentiating spermatogonia are derived from undifferentiated spermatogonia and consist of A1, A2, A3, A4, intermediate (In), and Type B spermatogonia.3,4,5,6,7 SSC self-renewal, spermatogonial proliferation, and spermatogonial differentiation are vital prerequisites for spermatogenesis. Self-renewal of SSC provides the foundation for the continuity of spermatogenesis. The initiation of spermatogenesis occurs when SSCs leave the self-renewal pathway and undergo several mitotic cell divisions to produce Apr and Aal spermatogonia, which then differentiate without mitotic division into A1 spermatogonia. The A1 spermatogonia undergo another series of mitotic divisions that lead to the successive formation of A2, A3, A4, In, and Type B spermatogonia. Thereafter, Type B spermatogonia divide to form preleptotene spermatocytes that enter meiosis to yield haploid spermatids, which then undergo spermiogenesis, leading to the production of spermatozoa.1

As a classical signaling molecule and a master regulatory protein kinase, MTOR can regulate a diverse array of cellular processes, such as growth, proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism, by forming two structurally and functionally distinct protein complexes termed mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2).8,9,10,11,12,13 In the clinical setting, MTORC1 plays a pivotal role in maintaining male reproductive health, and disrupted MTORC1 function impairs spermatogenesis, resulting in oligozoospermia or azoospermia and male sterility.14,15,16,17 By studying distinct mouse models, several groups showed that mTORC1 can affect spermatogenesis and male fertility by regulating spermatogonial development.18,19,20 For example, Busada et al.18 reported that in vivo inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin blocks spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation. Two other groups found that germ cell-specific deletion of tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) and tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2), two upstream inhibitors of mTORC1, both cause excessive differentiation of spermatogonia at the expense of their self-renewal.19,20 These findings indirectly suggested that, as a core component of mTORC1, MTOR itself may be involved in specific processes of spermatogonial development. In this study, we used stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8)-Cre to generate a germ cell-specific Mtor knockout (KO) mouse model to investigate the role of MTOR in spermatogonial development and male fertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animals used in our study were housed under a controlled lighting regime (14 h light; 10 h darkness) at 21°C–22°C with freely available food and water. Animal procedures were all approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). To generate germ cell-specific Mtor KO mice, male Stra8-Cre mice (No. 008208, The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with female Mtor-floxed mice (Mtorfl, No. 011009, The Jackson Laboratory) to generate Mtorfl/+; Stra8-Cre male mice. Then, Mtorfl/+; Stra8-Cre male mice were crossed with female Mtorfl/fl mice to produce Mtorfl/Δ; Stra8- Cre male mice, which we designated as Mtor KO mice. The Mtorfl/+; Stra8-Cre male littermates were used as controls. Genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated from tail biopsies was used for PCR-based genotyping and primers for identifying Cre and floxed Mtor alleles were designed as described previously.21,22,23,24 Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J female mice were purchased from the Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China).

Testicular morphological analysis and sperm counts

Testes were collected immediately after the animals were killed. Whole body weights and testicular weights were measured on a chemical balance. Images of testes were recorded with a stereoscopic microscope (MVX10, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Mature spermatozoa were collected from the cauda epididymidis and counted in a computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) machine (HTM-TOX IVOS sperm motility analyzer, Animal Motility, version 12.3A, Hamilton Thorne Research, Beverly, MA, USA) as described previously.25

Fertility test

To evaluate the fertility of male mice, five Mtor KO mice and their littermate controls were mated with WT C57 female mice at a ratio of 1:2, starting at 8 weeks of age. The duration of the fertility test was 4 months and the C57 female mice were replaced each month. Successful conception was defined by the presence of a vaginal plug and a subsequent visibly growing abdomen. Cages were monitored daily and litter sizes were recorded at delivery.20

BrdU labeling

The BrdU labeling was done as described previously.26 Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (50 μg g−1 body weight, B5002, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then killed 2 h later. Testes were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS solution.

Histology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF)

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses were performed as previously described with slight modifications.26 Briefly, for histological analysis, mouse testes were fixed overnight in Bouin's fixative, dehydrated with graded ethanol, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. The sections were then deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunohistochemical analysis, mouse testes were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% PFA, dehydrated with graded ethanol, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. The sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling in 0.01 mol l−1 sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 for 30 min, and cooled to room temperature. The sections were blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS for 60 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and added to the sections for overnight incubation at 4°C. For colorimetric detection, the samples were washed three times with PBS, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies, and developed using a DAB substrate kit (GK500705, Gene Tech Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). The samples were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with neutral balsam. For fluorescence detection, corresponding fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies were added to the washed sections and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with DAPI (2 μg ml−1) for 5 min, washed three times with PBS, and mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (S3023, Dako North America Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA). Primary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The sections were examined with an Olympus BX-51 microscope.

Supplementary Table 1.

Antibodies for immunohistochemistry and indirect immunofluorescence

| Protein | Vendor (catalog number) | Clonality | Host species | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTOR | Cell signaling technology (#2983T) | Monoclonal | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| DDX4 | Abcam (ab13840) | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 1:500 |

| GATA4 | Santa Cruz (sc-25310) | Monoclonal | Mouse | 1:500 |

| GFRA1 | R and D systems (AF560-SP) | Polyclonal | Goat | 1:200 |

| PLZF | Santa Cruz (sc-28319) | Monoclonal | Mouse | 1:200 |

| PLZF | Santa Cruz (sc-22839) | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| KIT | Cell signaling technology (#3074S) | Monoclonal | Rabbit | 1:50 |

| KI67 | Abcam (ab15580) | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| BrdU | Millipore (05-633) | Monoclonal | Mouse | 1:200 |

Cell quantification of IIF

For cell quantification, we counted the total number of germ cells positive for each marker in approximately 70 seminiferous tubules across distinct microscopic fields of the testicular sections. Total germ cell numbers were then divided by the numbers of seminiferous tubules to evaluate the relative population size of each subset of germ cells.

Statistics

For all statistical analyses, at least three biological replicates were taken. Data were analyzed by Prism Version 7.0a (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Assessment of statistical significance was performed with the unpaired t-test. P values are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; not significant (NS) as P > 0.05.

RESULTS

Generation of germ cell-specific Mtor KO mice

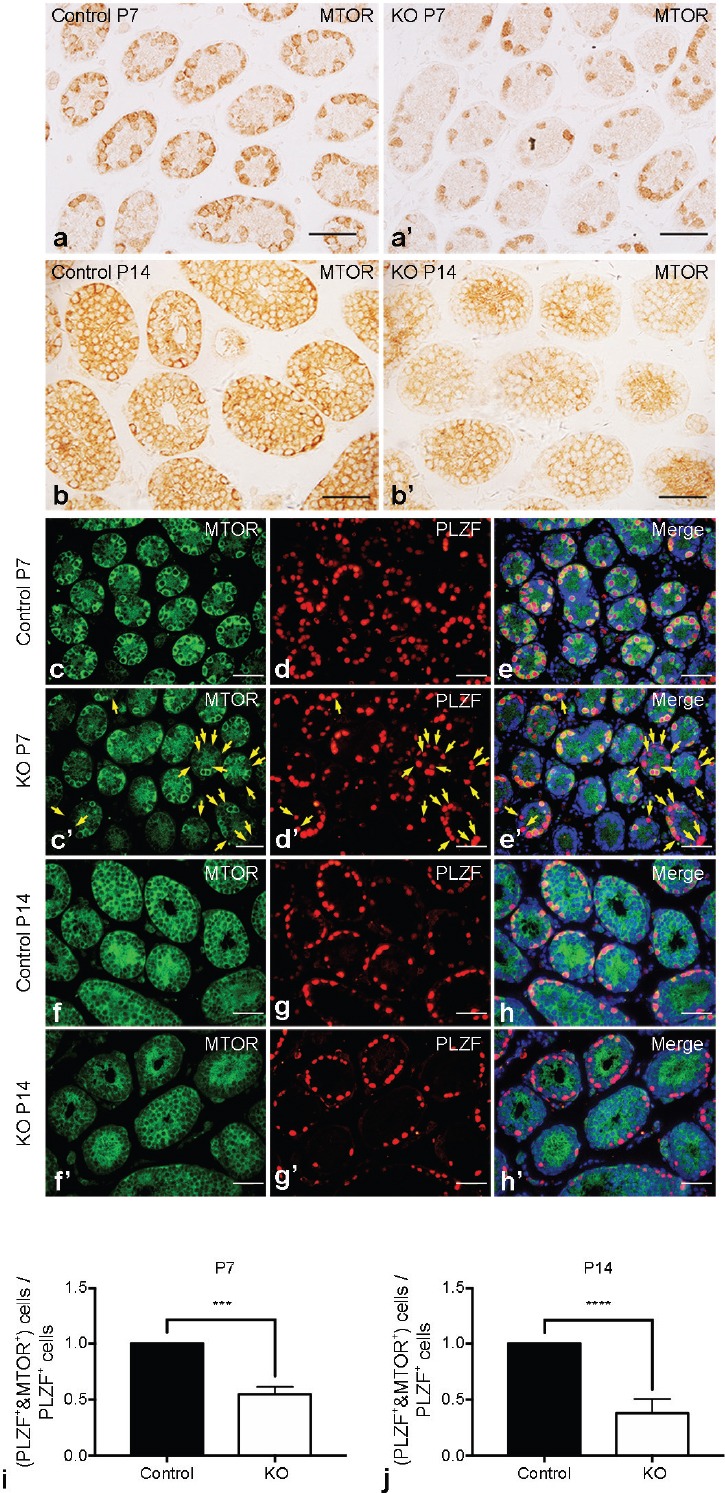

We generated germ cell-specific Mtor KO mice by utilizing Stra8-Cre-mediated gene deletion. Stra8-Cre is initially expressed at postnatal day 3 (P3) in a subset of undifferentiated spermatogonia and is detected through to preleptotene stage spermatocytes,24 so it is expected to direct floxed gene deletion in a substantial fraction of undifferentiated spermatogonia as well as differentiating spermatogonia and early meiotic spermatocytes.19 To assess the efficacy of Stra8-Cre-driven Mtor deletion, we first crossed MtorF/+; Stra8-Cre male mice with WT female mice and analyzed the genotypes of their offspring (Supplementary Figure 1 (909.9KB, tif) ). Our results indicated that the recombination and excision efficiency of the floxed Mtor allele was up to 98% (Table 1). Then, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) on testicular sections with an antibody against MTOR. A marked decrease in MTOR-positive (MTOR+) germ cells was found in the testes of Mtor KO mice (Figure 1a, 1a', 1b, 1b' and Supplementary Figure 2 (501.9KB, tif) ). Thereafter, we costained MTOR with promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF, also known as zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16, ZBTB16), a widely used marker for undifferentiated spermatogonia.27,28,29,30 Costaining found that while essentially all the PLZF-expressing cells were also positive for MTOR in the testes of control mice at postnatal day 7 (P7) and postnatal day 14 (P14), a large proportion (approximately 50% at P7 and approximately 60% at P14) of PLZF-positive (PLZF+) cells were devoid of MTOR expression in the testes of Mtor KO mice at the same ages (Figure 1c–1h, 1c'–1h' and 1i–1j). In addition, costaining of MTOR with GFRA1, a more restricted marker for undifferentiated spermatogonia,19,31,32,33 showed that the proportion of GFRA1+/MTOR+ germ cells were also significantly reduced (approximately 15% reduction at P7 and approximately 30% reduction at P14) in Mtor KO testes (Supplementary Figure 3 (1.2MB, tif) ). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Stra8-Cre successfully deleted Mtor in our KO mouse model and this germ cell-specific deletion was initiated in a subset of undifferentiated spermatogonia.

Table 1.

Quantitative data of genotyping and calculation of Mtor deletion efficiency

| Number of all pups | Number of Mtorfl/+ pups (number fl) | Number of MtorΔ/+ pups (number Δ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male 1 | 39 | 1 | 21 |

| Male 2 | 33 | 0 | 16 |

| Male 3 | 34 | 1 | 16 |

| Male 4 | 32 | 0 | 16 |

| Male 5 | 39 | 0 | 19 |

| Male 6 | 43 | 1 | 18 |

| Male 7 | 29 | 0 | 14 |

| Total | 249 | 3 | 120 |

| Efficiency of Mtor deletion (number Δ/[number fl+number Δ] × 100%) | 98% |

+: WT allele; fl: floxed allele; Δ: truncated allele

Figure 1.

Verification of MTOR deletion in Mtor KO testes. Representative images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of postnatal day 7 (P7) (a) control and (a') Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of postnatal day 14 (P14) (b) control and (b') Mtor KO mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. Representative images of indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) for (c) MTOR and (d) PLZF, and (e) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (c') MTOR and (d') PLZF, and (e') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Golden arrows indicate PLZF-positive cells with no MTOR expression. Representative images of IIF for (f) MTOR and (g) PLZF, and (h) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P14 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (f') MTOR and (g') PLZF, and (h') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P14 Mtor KO mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. Quantification of the proportion of PLZF+/MTOR+ germ cells in the testes of (i) P7 and (j) P14 control and Mtor KO mice. IHC: immunohistochemistry. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

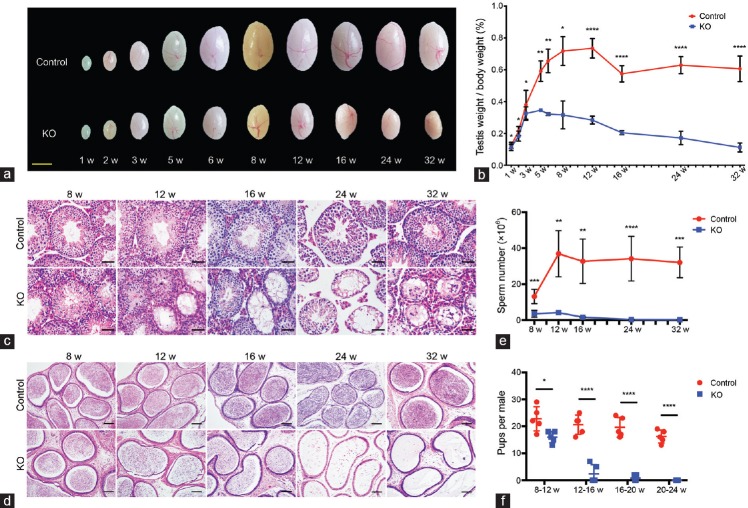

Mtor KO mice progressively lose their germ cells and fertility with age

With Stra8-Cre-driven Mtor deletion confirmed, we then examined its influence on testicular development. Gross morphological observation showed that the testicular size of Mtor KO mice was only slightly reduced compared with control mice within the first 3 weeks after birth, but ceased to increase at about 5 weeks of age, and then progressively declined with age compared with the testicular size of control mice (Figure 2a). Detailed statistical analysis of the relative testis weight (testis weight to body weight ratio) further supported this finding (Figure 2b). We speculate that the age-related reduction in testicular size and weight was caused by a continual loss of germ cells and thus conducted histological analyses on testicular sections from Mtor KO and control mice at different ages. H and E staining revealed an apparent decrease of germ cells in the testes of Mtor KO mice as early as 2 weeks of age and a reduction in the lumen of seminiferous tubules (Figure 2c and Supplementary Figure 4 (858.6KB, tif) ). Moreover, some of the seminiferous tubules of Mtor KO mice eventually became vacuolated, which started at about 8–12 weeks of age and gradually spread throughout the whole testis with age (Figure 2c). Consistent with findings in the testis, H and E staining of epididymal sections showed vacuolation. Although a considerable number of mature spermatozoa were present in the cauda epididymidis of Mtor KO mice at 8–12 weeks of age, they were fewer than those of control mice and were lost quickly with age. We found no spermatozoa in the cauda epididymidis of Mtor KO mice starting from 24 weeks of age (Figure 2d). Our computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA)-based data also supported this result (Figure 2e). To evaluate the effect of this age-dependent loss of germ cells on fertility, each male at 8 weeks of age was housed with two WT females for a period of 4 months, during which the WT females were replaced by two new ones each month. The control males bred normally throughout the test period; however, Mtor KO males exhibited a progressive loss of fertility, displaying a similar trend to the loss of mature spermatozoa (Figure 2f). Altogether, these results indicate that Mtor deletion disrupts testicular development and causes a progressive loss of germ cells in and fertility of male mice.

Figure 2.

Mtor KO mice progressively lose their germ cells and fertility with age. (a) Representative images of testes from control and Mtor KO mice aged from 1 to 32 weeks old. Scale bar = 3mm. (b) Quantification of testis weight to body weight ratios of control and Mtor KO mice at different ages. (c) Representative images of H and E-stained testicular sections of control and Mtor KO mice aged from 8 weeks to 32 weeks old. Scale bars = 50 μm. (d) Representative images of H and E-stained cauda epididymal sections of control and Mtor KO mice at different ages. Scale bars = 100 μm. (e) Quantification of spermatozoa collected from the cauda epididymidis of control and Mtor KO mice at different ages. (f) Statistical analysis of the fertility of control and Mtor KO male mice at distinct age intervals. H and E: hematoxylin and eosin. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

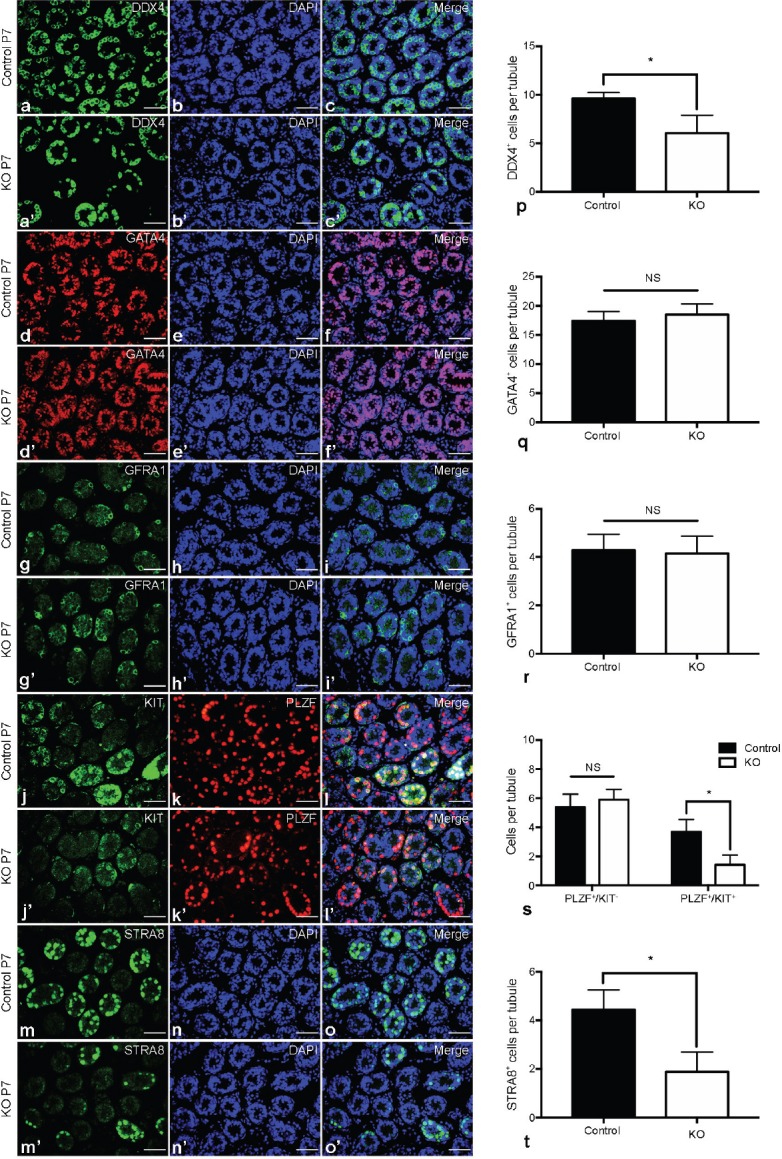

Spermatogonial differentiation in P7 Mtor KO testes

As mentioned above, Mtor deletion mediated by Stra8-Cre started in a subset of undifferentiated spermatogonia, so it was very likely to exert some influence on the biological functions of spermatogonia. To confirm this presumption, we assessed the cellular composition of testes from Mtor KO and control mice at P7, a time when the germ cells are mostly spermatogonia at different developmental stages.34 We performed immunofluorescence analysis with the germ cell marker DDX4 and the Sertoli cell marker GATA4 and found fewer DDX4-positive (DDX4+) germ cells in Mtor KO testes compared with control testes (Figure 3a–3c, 3a'–3c' and 3p), but no significant alteration in the number of GATA4-positive (GATA4+) Sertoli cells (Figure 3d–3f, 3d'–3f' and 3q). To determine the identity of the germ cells that were affected by Mtor deletion, we continued immunostaining with several molecular markers differentially expressed in distinct germ cell subpopulations to assess the population size of each subset of germ cells. We stained testicular sections with an antibody against glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 1 (GFRA1), which is abundantly and selectively expressed in a restricted population of undifferentiated spermatogonia.19,31,32,33 We found that the Mtor KO mice had an equal number of GFRA1-positive (GFRA1+) germ cells to that of control mice (Figure 3g–3i, 3g'–3i' and 3r). Then, costaining of PLZF with KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT), a bona fide marker for differentiating spermatogonia,35,36,37 revealed that the number of germ cells positive for PLZF but negative for KIT (PLZF+/KIT−) was not changed, but germ cells positive for both PLZF and KIT (PLZF+/KIT+) were markedly reduced in the testes of P7 Mtor KO compared with control mice (Figure 3j–3l, 3j'–3l' and 3s). Similarly, we also detected a reduced number of germ cells expressing STRA8 (Figure 3m–3o, 3m'–3o' and 3t), a differentiation marker mainly expressed in differentiating spermatogonia as well as preleptotene spermatocytes.26,38,39,40

Figure 3.

Spermatogonial differentiation in P7 Mtor KO testes. Representative images of indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) for (a) DDX4 and (b) DAPI, and (c) their merged images in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (a') DDX4 and (b') DAPI, and (c') their merged images in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (d) GATA4 and (e) DAPI, and (f) their merged images in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (d') GATA4 and (e') DAPI, and (f') their merged images in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (g) GFRA1 and (h) DAPI, and (i) their merged images in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (g') GFRA1 and (h') DAPI, and (i') their merged images in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (j) KIT and (k) PLZF, and (l) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (j') KIT and (k') PLZF, and (l') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (m) STRA8 and (n) DAPI, and (o) their merged images in the testes of P7 control mice. Representative images of IIF for (m') STRA8 and (n') DAPI, and (o') their merged images in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. Quantification of (p) DDX4+, (q) GATA4+, (r) GFRA1+, (s) PLZF+/KIT-, PLZF+/KIT+ and (t) STRA8+ germ cells in the testes of P7 control and Mtor KO mice. *P < 0.05.

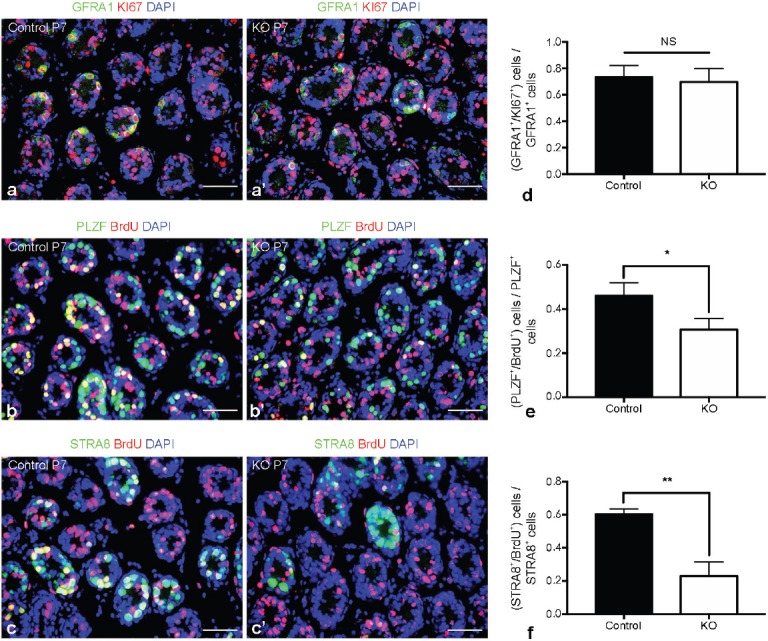

Spermatogonial proliferation in P7 Mtor KO testes

As an apparent defect in spermatogonial differentiation was detected, we investigated whether spermatogonial proliferation was also affected by Mtor deletion. We costained GFRA1, PLZF, and STRA8 with the proliferation marker KI67 or BrdU to assess the proliferation status of distinct subsets of spermatogonia. We found that the proliferation rate of GFRA1+ spermatogonia was not changed (Figure 4a, 4a' and 4d); however, the proportion of PLZF+/BrdU+ (Figure 4b, 4b' and 4e) and STRA8+/BrdU+ (Figure 4c, 4c' and 4f) germ cells were both decreased in P7 Mtor KO mice.

Figure 4.

Spermatogonial proliferation in P7 Mtor KO testes. Representative images of costained GFRA1 (green), KI67 (red) and DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 (a) control and (a') Mtor KO mice. Representative images of costained PLZF (green), BrdU (red) and DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 (b) control and (b') Mtor KO mice. Representative images of costained STRA8 (green), BrdU (red) and DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 (c) control and (c') Mtor KO mice. Scale bars = 50 μm. Quantification of the proportion of (d) GFRA1+/KI67+, (e) PLZF+/BrdU+ and (f) STRA8+/BrdU+ germ cells in the testes of P7 control and Mtor KO mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

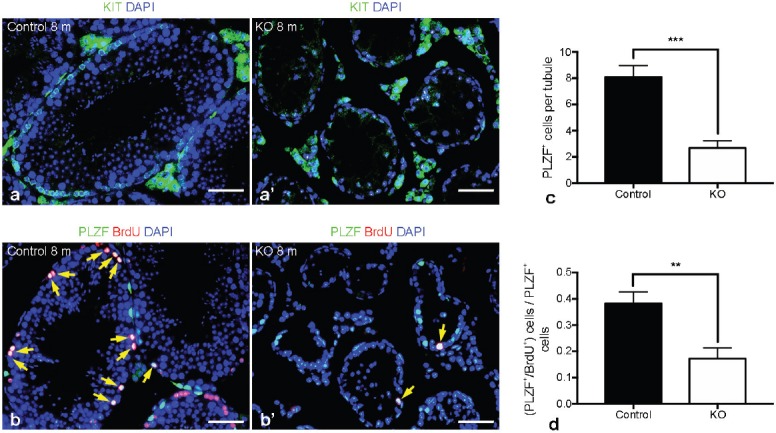

Spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation in adult Mtor KO mice at 8 months of age

To evaluate the long-term impact of Mtor deletion on the normal function of spermatogonia, we assessed the population size of different subsets of spermatogonia in the testes of adult Mtor KO mice at 8 months of age, an age when the seminiferous tubules all became vacuolated. We detected no KIT+ differentiating spermatogonia in the testes of 8-month-old Mtor KO mice (Figure 5a and 5a'), but PLZF+ undifferentiated spermatogonia were easily found (Figure 5b and 5b'). In addition, quantitative analysis revealed that the number of PLZF+ germ cells was markedly decreased (Figure 5c). Costaining of PLZF with BrdU showed that the proportion of PLZF+/BrdU+ germ cells also declined in Mtor KO mice (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation in adult Mtor KO mice at 8 months of age. Representative images of costained KIT (green) and DAPI (blue) in the testes of 8-month-old (a) control and (a') Mtor KO mice. Representative images of costained PLZF (green), BrdU (red) and DAPI (blue) in the testes of 8-month-old (b) control and (b') Mtor KO mice. Golden arrows indicate PLZF+/BrdU+ germ cells. Scale bars = 50 μm. (c) Quantification of PLZF+ germ cells in the testes of 8-month-old control and Mtor KO mice. (d) Quantification of the proportion of PLZF+/BrdU+ germ cells in the testes of 8-month-old control and Mtor KO mice. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Spermatogonial development is a vital prerequisite for spermatogenesis, and considerable research has been devoted to unraveling the details and exact mechanisms underlying the development of spermatogonia, including SSC self-renewal, spermatogonial proliferation, and spermatogonial differentiation. In the current study, we used Stra8-Cre to generate a germ cell-specific Mtor KO mouse model to investigate the role of MTOR in spermatogonial development. Our results indicate that MTOR is required for spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation. When MTOR was deleted, the transition from undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia was greatly inhibited, leading to a marked reduction of differentiating spermatogonia. Moreover, MTOR deficiency also impeded the proliferation of spermatogonia, which further diminished the spermatogonia pool as well as the whole germ cell population. These outcomes are consistent with several previous studies. For instance, previous studies reported that mTORC1 is involved in RA-induced translation of several genes required for spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation, and inhibition of mTORC1 activity by rapamycin severely suppresses spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation.18,41 Toward the end of our study, these researchers published work in which they ablated Mtor more thoroughly in male germ cells using Ddx4-Cre to explore its role in spermatogonial development.42 According to their recent data, Mtor deletion greatly impeded the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia without disturbing their survival and self-renewal.42 Another two groups created mouse KO models with male germ cell-specific deletion of two upstream inhibitors of mTORC1, TSC1 and TSC2. They found that the ablation of TSC1 and TSC2 caused hyperactivation of MTORC1 signaling and excessive differentiation of undifferentiated spermatogonia, an effect opposite to that caused by MTOR deletion or mTORC1 inhibition.19,20 These results, together with our own findings, reveal that MTOR is indispensable for the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia, and mTORC1 activity seems to be positively correlated with the differentiation of spermatogonia.

Our current study found that all the phenotypes caused by Stra8-Cre-mediated Mtor deletion seemed to occur in an age-dependent manner. For instance, although our Mtor KO mice became sterile at about 6 months old, their fertility was only partially lost when they were young. Interestingly, the incomplete phenotype of young adults observed in our study was also found in the studies of TSC1 and TSC2 mentioned above.19,20 In both studies, a mixture of normal-appearing seminiferous tubules were found adjacent to degenerating tubules in the testes of 8–9-week-old KO mice, even when TSC1 and TSC2 were more extensively ablated using Ddx4-Cre.19,20 The deletion of TSC1 driven by Ddx4-Cre resulted in an approximately 60% decline in epididymal sperm number as well as a partial loss of fertility.20 We had speculated that it might be an intrinsic property of MTOR (mTORC1) to affect spermatogonial development in a mild and progressive manner when its activity is either removed or excessively activated. However, our assumption was negated by recent work from the Geyer group, in which they abolished MTOR function earlier and more thoroughly using Ddx4-Cre and then detected a more complete phenotype.42 Specifically, all seminiferous tubules in Ddx4-Cre-mediated Mtor KO mice contained vacuoles as early as P18 and not a single spermatozoon was found in the cauda epididymidis throughout the whole reproductive lifespan.42 This research, combined with our results, indicates that either the timing or efficiency of Mtor deletion mediated by different Cre lines causes the variation of phenotypes between the two distinct Mtor KO mouse models. From our results, the recombination and excision efficiency of floxed Mtor allele was up to 98%, demonstrating that Stra8-Cre drove a nearly complete Mtor deletion within the male germline. As the possibility for inefficient Mtor deletion was excluded, it seems that the incomplete phenotype found in our study was caused by a delayed initiation of Mtor deletion driven by Stra8-Cre. Stra8-Cre is active in a particular subset of undifferentiated spermatogonia that have already obtained a high propensity for differentiation, but is inefficient in those still possessing high self-renewal potential,19 so the Stra8-Cre-induced Mtor deletion within undifferentiated spermatogonia may start at a relatively late stage when a considerable amount of MTOR proteins were already expressed. As it takes time to degrade all residual MTOR proteins, some undifferentiated spermatogonia may escape the differentiation arrest caused by MTOR deficiency and maintain a few rounds of spermatogenesis for a limited period of time. We detected weak expression of MTOR proteins in the residual germ cells of Mtor KO mice at different ages, providing supportive evidence for this hypothesis. However, more comprehensive examinations are still needed to fully confirm this proposal.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JC participated in the design of the study, carried out the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. ZBL helped perform the animal experiments. YLZ and MHT contributed to the design of the study, helped interpret the data, and revised the manuscript. YCZ and YPL supervised the study, participated in its design and coordination, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declared no competing interests.

Mating scheme for Mtor deletion efficiency assessment.

Weak expression of MTOR proteins remained in the residual germ cells of Mtor KO mice. Representative ×40 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of control mice at (a) 8 weeks, (b) 16 weeks, (c) 24 weeks and (d) 32 weeks of age. Representative ×40 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes Mtor KO mice at (a') 8 weeks, (b') 16 weeks, (c') 24 weeks and (d') 32 weeks of age. Bar = 50 µm. Representative ×100 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of control mice at (e) 8 weeks, (f) 16 weeks, (g) 24 weeks and (h) 32 weeks of age. Representative ×100 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes Mtor KO mice at (e') 8 weeks, (f') 16 weeks, (g') 24 weeks and (h') 32 weeks of age. Bar = 20 µm. IHC: immunohistochemistry.

Quantification of the efficiency of MTOR deletion in GFRA1+ germ cells. Representative images of indirect IIF for (a) GFRA1 and (b) MTOR, and (c) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of postnatal day 7 (P7) control mice. Representative images of IIF for (a') GFRA1 and (') MTOR, and (c') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (d) GFRA1 and (e) MTOR, and (f) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of postnatal day 14 (P14) control mice. Representative images of IIF for (d') GFRA1 and (e') MTOR, and (f') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P14 Mtor KO mice. Bar = 50 µm. Golden arrows indicate GFRA1-positive cells with no MTOR expression. Quantification of the proportion of GFRA1+/MTOR+ germ cells in the testes of (g) P7 and (h) P14 control and Mtor KO mice. IIF: immunofluorescence. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

An apparent loss of germ cells in the testes of Mtor KO mice found as early as 2 weeks of age. Representative images of H&E-stained testicular sections of control mice at (a) 1 week, (b) 2 weeks, (c) 3 weeks, (d) 4 weeks and (e) 5 weeks of age. Representative images of H&E-stained testicular sections of Mtor KO mice at (a') 1 week, (b') 2 weeks, (c') 3 weeks, (d') 4 weeks and (e') 5 weeks of age. Bar = 50 µm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Qiang Liu, Dr. Yanfei Ru, and Dr. Guangxin Yao for critical reading of this manuscript. We also want to thank Zimei Ni for mouse handling and Aihua Liu for technical assistance in immunohistochemical analysis. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (NO. 2014CB943103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31671203 and NO. 31471104), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (NO. 17JC1420100).

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Asian Journal of Andrology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oatley JA, Brinster RL. Regulation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi. 2008;24:263–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rooij DG, Russell LD. All you wanted to know about spermatogonia but were afraid to ask. J Androl. 2000;21:776–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mecklenburg JM, Hermann BP. Mechanisms regulating spermatogonial differentiation. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2016;58:253–87. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-31973-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Rooij DG. The nature and dynamics of spermatogonial stem cells. Development. 2017;144:3022–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.146571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Shinohara T. Spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:163–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord T, Oatley JM. A revised Asingle model to explain stem cell dynamics in the mouse male germline. Reproduction. 2017;154:R55–64. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida S. Elucidating the identity and behavior of spermatogenic stem cells in the mouse testis. Reproduction. 2012;144:293–302. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–94. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bererhi L, Flamant M, Martinez F, Karras A, Thervet E, et al. Rapamycin-induced oligospermia. Transplantation. 2003;76:885–6. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000079830.03841.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skrzypek J, Krause W. Azoospermia in a renal transplant recipient during sirolimus (rapamycin) treatment. Andrologia. 2007;39:198–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutsch MA, Kaczmarek I, Huber S, Schmauss D, Beiras-Fernandez A, et al. Sirolimus-associated infertility: case report and literature review of possible mechanisms (vol 7, pg 2414, 2007) Am J Transplant. 2008;8:472–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuber J, Anglicheau D, Elie C, Bererhi L, Timsit MO, et al. Sirolimus may reduce fertility in male renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1471–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busada JT, Niedenberger BA, Velte EK, Keiper BD, Geyer CB. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) is required for mouse spermatogonial differentiation in vivo. Dev Biol. 2015;407:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs RM, La HM, Makela JA, Kobayashi T, Noda T, et al. Distinct germline progenitor subsets defined through Tsc2-mTORC1 signaling. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:467–80. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CX, Wang ZL, Xiong Z, Dai HQ, Zou ZP, et al. mTORC1 activation promotes spermatogonial differentiation and causes subfertility in mice. Biol Reprod. 2016;95:97. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.140947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gangloff YG, Mueller M, Dann SG, Svoboda P, Sticker M, et al. Disruption of the mouse mTOR gene leads to early postimplantation lethality and prohibits embryonic stem cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9508–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9508-9516.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risson V, Mazelin L, Roceri M, Sanchez H, Moncollin V, et al. Muscle inactivation of mTOR causes metabolic and dystrophin defects leading to severe myopathy. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:859–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao JQ, Ma HY, Schuster A, Lin YM, Yan W. Incomplete cre-mediated excision leads to phenotypic differences between Stra8-iCre; Mov10l1(lox/lox) and Stra8-iCre; Mov10l1(lox/) mice. Genesis. 2013;51:481–90. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadate-Ngatchou PI, Payne CJ, Dearth AT, Braun RE. Cre recombinase activity specific to postnatal, premeiotic male germ cells in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2008;46:738–42. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou YC, Ru YF, Wang CM, Wang SL, Zhou ZM, et al. Tripeptidyl peptidase II regulates sperm function by modulating intracellular Ca2+ stores via the ryanodine receptor. PLos One. 2013;8:e66634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Ma L, Hogarth C, Wei G, Griswold MD, et al. Retinoid signaling controls spermatogonial differentiation by regulating expression of replication-dependent core histone genes. Development. 2016;143:1502–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.135939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buaas FW, Kirsh AL, Sharma M, McLean DJ, Morris JL, et al. Plzf is required in adult male germ cells for stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2004;36:647–52. doi: 10.1038/ng1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti G, Manova K, et al. Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:653–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbs RM, Seandel M, Falciatori I, Rafii S, Pandolfi PP. Plzf regulates germline progenitor self-renewal by opposing mTORC1. Cell. 2010;142:468–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobbs RM, Fagoonee S, Papa A, Webster K, Altruda F, et al. Functional antagonism between Sall4 and Plzf defines germline progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:284–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naughton CK, Jain S, Strickland AM, Gupta A, Milbrandt J. Glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor-mediated RET signaling regulates spermatogonial stem cell fate.(vol 74, pg 314, 2006) Biol Reprod. 2006;75:660. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.047365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa T, Sharma M, Nabeshima Y, Braun RE, Yoshida S. Functional hierarchy and reversibility within the murine spermatogenic stem cell compartment. Science. 2010;328:62–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1182868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grasso M, Fuso A, Dovere L, De Rooij DG, Stefanini M, et al. Distribution of GFRA1-expressing spermatogonia in adult mouse testis. Reproduction. 2012;143:325–32. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellve AR, Cavicchia JC, Millette CF, O’Brien DA, Bhatnagar YM, et al. Spermatogenic cells of the prepuberal mouse. Isolation and morphological characterization. J Cell Biol. 1977;74:68–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mithraprabhu S, Loveland KL. Control of KIT signalling in male germ cells: what can we learn from other systems? Reproduction. 2009;138:743–57. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niedenberger BA, Busada JT, Geyer CB. Marker expression reveals heterogeneity of spermatogonia in the neonatal mouse testis. Reproduction. 2015;149:329–38. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrans-Stassen BH, Van de Kant HJ, De Rooij DG, Van Pelt AM. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5894–900. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.OuladAbdelghani M, Bouillet P, Decimo D, Gansmuller A, Heyberger S, et al. Characterization of a premeiotic germ cell-specific cytoplasmic protein encoded by Stra8, a novel retinoic acid-responsive gene. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:469–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Q, Nie R, Li Y, Friel P, Mitchell D, et al. Expression of stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8) in spermatogenic cells induced by retinoic acid: an in vivo study in Vitamin A-sufficient postnatal murine testes. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:35–42. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endo T, Romer KA, Anderson EL, Baltus AE, de Rooij DG, et al. Periodic retinoic acid-STRA8 signaling intersects with periodic germ-cell competencies to regulate spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2347–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505683112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busada JT, Chappell VA, Niedenberger BA, Kaye EP, Keiper BD, et al. Retinoic acid regulates Kit translation during spermatogonial differentiation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2015;397:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serra ND, Velte EK, Niedenberger BA, Kirsanov O, Geyer CB. Cell-autonomous requirement for mammalian target of rapamycin (Mtor) in spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2017;96:816–28. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mating scheme for Mtor deletion efficiency assessment.

Weak expression of MTOR proteins remained in the residual germ cells of Mtor KO mice. Representative ×40 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of control mice at (a) 8 weeks, (b) 16 weeks, (c) 24 weeks and (d) 32 weeks of age. Representative ×40 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes Mtor KO mice at (a') 8 weeks, (b') 16 weeks, (c') 24 weeks and (d') 32 weeks of age. Bar = 50 µm. Representative ×100 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes of control mice at (e) 8 weeks, (f) 16 weeks, (g) 24 weeks and (h) 32 weeks of age. Representative ×100 images of IHC for MTOR in the testes Mtor KO mice at (e') 8 weeks, (f') 16 weeks, (g') 24 weeks and (h') 32 weeks of age. Bar = 20 µm. IHC: immunohistochemistry.

Quantification of the efficiency of MTOR deletion in GFRA1+ germ cells. Representative images of indirect IIF for (a) GFRA1 and (b) MTOR, and (c) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of postnatal day 7 (P7) control mice. Representative images of IIF for (a') GFRA1 and (') MTOR, and (c') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P7 Mtor KO mice. Representative images of IIF for (d) GFRA1 and (e) MTOR, and (f) their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of postnatal day 14 (P14) control mice. Representative images of IIF for (d') GFRA1 and (e') MTOR, and (f') their merged images with DAPI (blue) in the testes of P14 Mtor KO mice. Bar = 50 µm. Golden arrows indicate GFRA1-positive cells with no MTOR expression. Quantification of the proportion of GFRA1+/MTOR+ germ cells in the testes of (g) P7 and (h) P14 control and Mtor KO mice. IIF: immunofluorescence. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

An apparent loss of germ cells in the testes of Mtor KO mice found as early as 2 weeks of age. Representative images of H&E-stained testicular sections of control mice at (a) 1 week, (b) 2 weeks, (c) 3 weeks, (d) 4 weeks and (e) 5 weeks of age. Representative images of H&E-stained testicular sections of Mtor KO mice at (a') 1 week, (b') 2 weeks, (c') 3 weeks, (d') 4 weeks and (e') 5 weeks of age. Bar = 50 µm.