Abstract

Suicide ideation is an inherently dynamic construct. Previous research implicates different temporal patterns in suicide ideation among individuals who have made multiple suicide attempts as compared to individuals who have not. Temporal patterns among first-time attempters might therefore distinguish those who eventually make a second suicide attempt. To test this possibility, the present study used a dynamical systems approach to model change patterns in suicide ideation over the course of brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (12 sessions total) among 33 treatment-seeking active duty Soldiers with one prior suicide attempt. Variable-centered models were constructed to determine if change patterns differed between those with and without a follow-up suicide whereas person-centered models were constructed to determine if within-person change patterns were associated with eventual suicide attempts. Severity of suicide ideation was not associated with the occurrence of suicide attempts during follow-up, but person-centered temporal patterns were. Among those who made an attempt during follow-up, suicide ideation demonstrated greater within-person variability across treatment. Results suggest certain change processes in suicide ideation may characterize vulnerability to recurrent suicide attempt among first-time attempters receiving outpatient behavioral treatment. Nonlinear dynamic models may provide advantages for suicide risk assessment and treatment monitoring in clinical settings.

Keywords: suicide, risk assessment, military, nonlinear models, dynamical systems theory, fluid vulnerability theory

The fluid vulnerability theory of suicide (Rudd, 2006) posits that suicide risk is best characterized as a temporal process that possesses both stable and dynamic properties, such that certain aspects of suicide risk persist over time whereas other aspects fluctuate or change. Considering both stability and dynamism is therefore important for understanding the conditions under which suicidal behaviors are more likely to occur (i.e., high risk states) and the conditions under which suicidal behaviors are less likely to occur (i.e., low risk states). One temporal process often assumed to be associated with the shift from a low risk state to a high risk state is an increase in the severity of suicide ideation. Most suicide risk screening and assessment approaches used in clinical settings are based on this assumption, but research suggests this assumption has only limited utility (Franklin et al., 2017).

A likely contributor to this limitation is the inherently dynamic nature of suicide ideation itself. Accumulating research using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods shows that suicide ideation tends to vary significantly within individuals over time (Kleiman & Nock, 2018). In one study using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods, for instance, over 90% of individuals experienced a change in suicide ideation severity that exceeded one standard deviation in magnitude during periods of time as brief as only a few hours (Kleiman et al., 2017). The temporal process of suicide ideation is therefore nonlinear in nature, consistent with the fluid vulnerability theory’s assertion that suicide risk possesses dynamic properties. Given the inherently nonlinear nature of suicide ideation in general, it stands to reason that the transition from a low risk state (in which suicidal behavior in unlikely) to a high risk state (in which suicidal behavior is more likely to emerge) is also nonlinear in nature. This possibility is implied by the fluid vulnerability theory, which hypothesizes that suicidal behaviors emerge within the context of high risk states as a result of complex interactions among environmental, affective, cognitive, and physiological variables. The interactions manifest as fluctuations in suicide risk.

Low risk states also involve interactions among environmental, affective, cognitive, and physiological variables, but these interactions are expected to be qualitatively distinct from the interactions that characterize high risk states. Indeed, a central property of emergent phenomena like suicidal behavior is the existence of different change patterns across different states (cf. Jaeger & Monk, 2014). Fluctuations in suicide risk that characterize low risk states are therefore expected to differ from the fluctuations in suicide risk that characterize high risk states. Several lines of evidence support this possibility.

Among patients who have attempted suicide, marked increases in the variability of suicide ideation in the days and hours immediately preceding their suicide attempts has been reported (Bagge, Littlefield, Conner, Schumacher, & Lee, 2014; Millner et al., 2017). These data converge with the subjective reports of patients who have attempted suicide, the majority of whom describe their suicide ideation during the time leading up to the attempt as a fluctuating process rather than a linear process of intensification (Wyder & DeLeo, 2007). A handful of studies have also found that fluctuations in suicide ideation are significantly larger and more rapid among those with a history of multiple suicide attempts as compared to those who have never attempted suicide or made only a single suicide attempt (Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Witte et al., 2005). A history of multiple suicide attempts has also been associated with more frequent and longer lasting high risk states (Bryan, Clemans, Leeson, & Rudd, 2015; Joiner, Rudd, Rouleau, & Wagner, 2000; Joiner & Rudd, 2000) as well as larger fluctuations in suicide ideation (Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Witte et al., 2015). Taken together, these studies suggest the emergence of suicidal behavior may be characterized by unique temporal patterns in suicide ideation. If confirmed, such research could implicate new strategies for improving suicide risk screening and assessment.

An important limitation of many of these studies is the use of retrospective assessement methods that could be vulnerable to memory distortion and/or responder bias. A second limitation of existing reseach is the examination of change processes across individuals who have already engaged in suicidal behaviors. Research utilizing prospective designs is needed to determine whether or not certain nonlinear change processes can distinguish those who will eventually engage in suicidal behaviors from those who will not. This issue holds considerable relevance for clinical settings. If clinicians were better able to identify which patients are most vulnerable to engaging in recurrent suicidal behavior, treatment plans could potentially be adjusted to better target and mitigate this risk. Although EMA research holds considerable promise for addressing these limitations, these assessment methods are not routinely used by clinicians and practitioners. EMA research further suggests that fluctuations in suicide ideation occur during windows of time as narrow as a few hours (Kleiman & Nock, 2018), but in clinical settings, repeated assessment of suicide ideation and other psychological phenomena is typically spaced across wider intervals of time (e.g., once per week). Examining patterns of change in suicide ideation using methods commonly used in clinical practice are therefore needed to determine if nonlinear change processes observed under these conditions have the potential to provide meaningful and useful information for identifying which patients are most likely to engage in suicidal behavior.

Consistent with this objective, the aim of the present study was to determine if temporal patterns in suicide ideation, assessed at each psychotherapy appointment, could distinguish patients who made a suicide attempt within two years of initiating outpatient mental health treatment for elevated suicide risk. To achieve this aim, we used data from a recently completed clinical trial testing the efficacy of brief cognitive behavivoral therapy for suicide prevention (BCBT) among active duty military personnel (Rudd et al., 2017). As noted previously, existing research suggests that certain properties of nonlinear change processes characterize individuals who are already known to have a history of multiple suicide attempts (Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Witte et al., 2005), but these studies have not examined if change processes distinguish first-time suicide attempters who will eventually make a second suicide attempt from those who will not. In the present study, we therefore sought to determine if temporal patterns in suicide ideation were significantly associated with the recurrence of suicide attempts among patients who, at the time of intake, had a history of only one suicide attempt (i.e., first-time attempters).

Methods

Participants

Participants for the present study included a subgroup of active duty U.S. Army personnel referred for a randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of BCBT as compared to treatment as usual (TAU) for the prevention of suicide attempts (Rudd et al., 2015). Eligibility criteria for the parent study included being an active duty U.S. Soldier, 18 years of age or older, and reporting suicide ideation within the past week and/or a suicide attempt within the past month. As noted in Rudd et al., a total of 176 Soldiers provided informed consent to enroll in the study, at which point they completed a baseline assessment including structured clinical interviews and self-report measures. Of these, 152 met eligibility criteria and were randomized to either BCBT (n=76) or treatment as usual (n=76).

The subgroup selected for this study entailed 33 Soldiers who were assigned to receive BCBT and had a history of one previous suicide attempt at baseline. This subgroup was specifically selected for several reasons. First, the BCBT condition included an assessment of suicide ideation at the beginning of each therapy session. Second, previous research indicates that treatment-seeking military personnel with a history of multiple suicide attempts are an especially high risk subgroup of patients (Bryan, Clemans, Leeson, & Rudd, 2015; Bryan & Rudd, 2015; Joiner & Rudd, 2000; Rudd, Joiner, & Rajab, 1996); preventing the recurrence of suicide attempts among first-time attempters therefore has important implications for suicide prevention. Third, research indicates that patients who begin treatment with a history of multiple suicide attempts display unique change patterns in suicide ideation (Bryan & Rudd, 2017). We therefore sought to determine if change patterns among patients who begin treatment with a history of only one suicide attempt would differ between those who eventually make a second suicide attempt (i.e., becoming a multiple attempter) from those who do not.

The 33 participants included in the present study included 29 (87.9%) men and 4 (12.1%) women ranging in age from 19 to 44 years (M=26.2, SD=6.0). All participants were either junior enlisted (n=27, 81.8%) or noncommissioned officer (n=6, 18.2%) in rank. Self-reported racial identity was predominantly white (n=26, 78.8%), followed by black (n=3, 9.1%), Native American (n=2, 6.1%), Asian (n=1, 3.0%), Pacific Islander (n=1, 3.0%), and other (n=1, 3.0%). Five (n=15.2%) participants additionally self-identified as Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.

Procedures

Upon signing the informed consent document, Soldiers underwent an evaluation for eligibility that included a battery of self-report scales and clinician-administered interviews. Soldiers meeting eligibility criteria were then randomized to either the BCBT or TAU condition using a computerized randomization algorithm. Follow-up assessments were conducted at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postbaseline, and included structured clinical interviews and self-report measures. Additional details about the parent trial’s methodology, including a CONSORT chart, are published elsewhere (Rudd et al., 2015). Relevant to the present study, participants randomized to the BCBT condition were administered a brief self-report symptom scale prior to the start of each therapy session. This scale included the suicide ideation item of the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), described below in the Instruments section.

Instruments

Suicide attempts were assessed using the Suicide Attempt Self Injury Interview (SASII; Linehan et al., 2006), a structured clinician-administered interview that assesses a range of factors associated with self-directed violent behavior (e.g., intent, method, and medical severity). The SASII has demonstrated high interrater reliability and validity as compared to other methods of assessing and tracking the occurrence of suicide attempts, to include high concordance (>80% agreement) between weekly reports of self-directed violent behaviors and retrospective recall of these behaviors. As noted above, the SASII was administered at baseline and 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postbaseline.

Suicide ideation was assessed at the beginning of every therapy session using item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). This item assesses the severity of suicide ideation on a 4-point scale: I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself (0); I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out (1); I would like to kill myself (2); and I would kill myself if I had the chance (3). Higher scores therefore indicate more severe suicidal intent. Higher scores are significantly associated with higher rates of later suicide death and repeat suicide attempts (Green et al., 2015). Research further suggests the use of this single item for assessing severity of suicide ideation is valid and comparable to the results of much longer suicide ideation scales (Desseilles et al., 2012). This item was assessed at each BCBT session.

Data Analytic Approach

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 24. Because BCBT was designed to be a 12-session treatment protocol, suicide ideation scores from the first 12 sessions only were used for analyses. Data from the first eleven sessions were available from most (>70%) participants and were available from 52% of participants for the twelfth session. Missing data quickly increased thereafter due to the small proportion of participants attending more than 12 treatment sessions. Sensitivity analyses were conducted comparing the results of analyses using all data points and the results of analyses using data from only the first 12 sessions. Differences were minimal and did not alter interpretations or conclusions. We therefore reported findings based on the first 12 sessions of BCBT only.

Analyses were conducted using two approaches. First, we used multilevel growth models with suicide ideation scores nested within participants. Second, we used a dynamical systems approach with change in suicide ideation scores nested within participants. For both approaches, we constructed variable-centered models and person-centered models to consider both between-person and within-person effects. The variable-centered models enabled us to compare differences in mean suicide ideation across patients who made a second suicide attempt and those who did not (i.e., between-person effects) whereas the person-centered models enabled us to examine how change in suicide ideation within individuals was associated with the emergence of a second suicide attempt (i.e., within-person effects).

In the linear growth models, BDI9 scores were selected as the outcome variable and predictors included suicide attempt group and time, which was measured using session number. Session number was used as our time variable because it is a commonly-used and practical method for clinicians to gauge the passage of time during treatment. The two-way interaction of suicide attempt group and session number was also calculated and added to the model to test between-group differences in slopes. Second, we used a dynamical systems approach in which change in BDI9 from one session to the next session (i.e., ΔBDI9 = BDI9t+1 – BDI9t) served as the outcome variable. This method enabled us to compare differences in change patterns across patients who made a second suicide attempt and those who did not. In these models, fixed effects included (a) suicide attempt group, (b) session number, and (c) suicide ideation score from the current session (i.e., BDI9t). The use of suicide ideation at the current session as a predictor of change in suicide ideation from the current session to the next session enabled us to examine the degree to which suicide ideation tended to resist change or maintain homeostatic equilibrium over time. Because we modeled change in suicide ideation as our outcome, increasingly positive coefficient values for the model’s fixed effects would reflect, respectively, (a) greater variability in suicide ideation among those who made a suicide attempt, (b) increasing variability in suicide ideation over the course of treatment, and (c) less resistance to change. Increasingly negative coefficient values, by contrast, would reflect (a) less variability in suicide ideation among those who made a suicide attempt, (b) decreasing variability in suicide ideation over the course of treatment, and (c) greater resistence to change. To determine if temporal patterns differed among patients who did and did not make a suicide attempt during follow-up, the three-way interaction of suicide attempt group, BDI9t, and session number was calculated and added to the model along with all lower-order interaction terms.

In all models, an unstructured covariance matrix was selected based on comparison of fit statistics relative to models using other covariance matrices. Random effects were specified for the intercept and session number. In the dynamical systems model, a random effect was also specified for BDIt. Time was centered at baseline (i.e., session=0), thereby enabling interpretations to be made relative to the pretreatment baseline assessment. Statistically significant interactions were decomposed by attempt group to clarify how the temporal dynamics of suicide ideation differed across those made a suicide attempt and those who did not. Missing data were handled using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

With respect to statistical power for a two-tailed α<0.05, 33 participants provided 80% power to detect a small effect (f=0.15) when assuming a moderate correlation among repeated measurements (r=0.50) and 12 repeated measurements. When the correlation among repeated measurements was assumed to be smaller (i.e., r=0.20), power remained sufficient to detect an effect size of f=0.19.

Results

At baseline, suicide ideation severity score ranged from 0 to 3 (M=1.0, SD=0.8). Nine participants (27.3%) endorsed “I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself,” 15 (45.5%) endorsed “I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out,” 8 (24.2%) endorsed “I would like to kill myself,” and one (3.0%) endorsed “I would kill myself if I had the chance.” Six participants (18%) subsequently made a suicide attempt during or after treatment, thereby transitioning from first-time attempters to “multiple attempters.” Three suicide attempts occurred during treatment (i.e., within the first three months postbaseline) and three occurred within 13 months of treatment completion (range=20 to 500 days postbaseline, median=151 days [interquartile range=405], mean=239.1 days [SD=198.6]).

Results of linear growth models

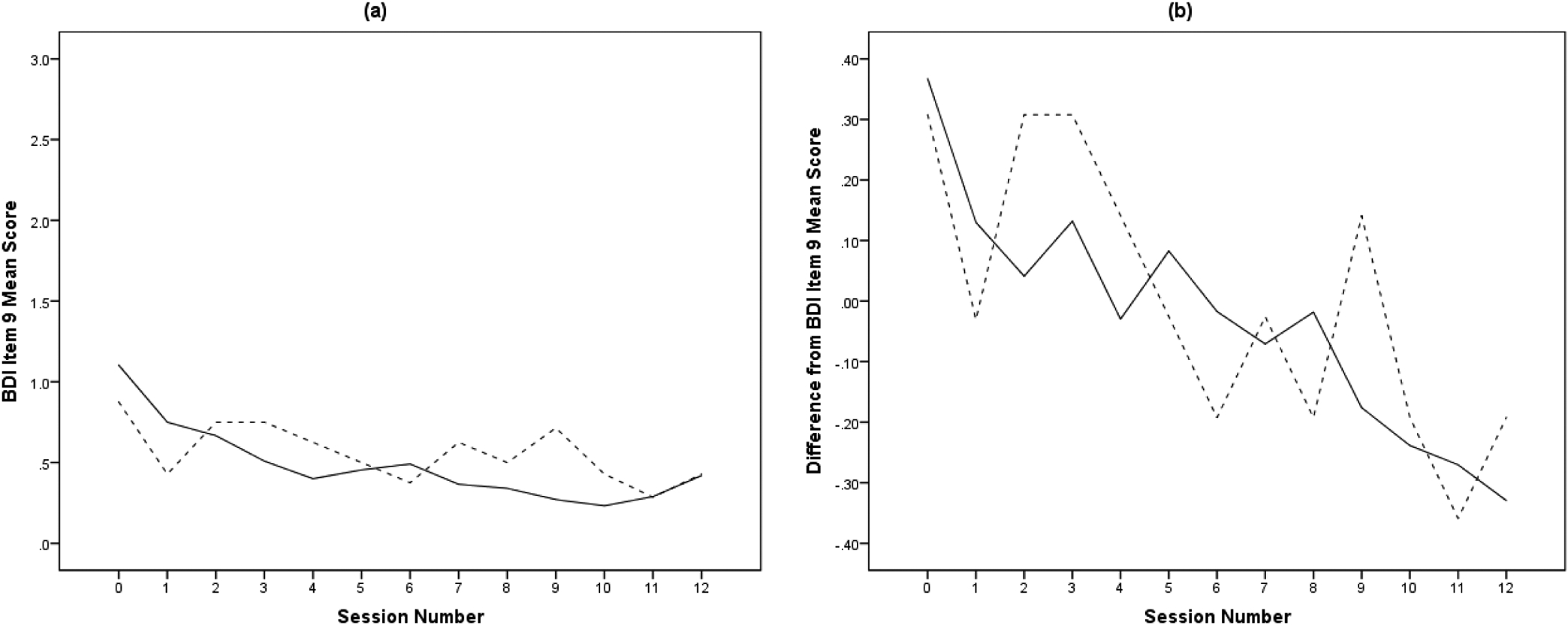

Mean BDI9 scores and person-centered BDI9 scores across treatment sessions are plotted in Figure 1. From baseline to the twelfth session, results of the unconditional growth model indicated mean severity of suicide ideation significantly decreased across treatment (B=−0.05, SE=0.01, p<.001). At the group level, mean suicide ideation severity was slightly higher at most time points among those who attempted suicide (Figure 1a). At the individual level, however, mean suicide ideation among those who attempted suicide was just as likely to be more severe as it was to be less severe as compared to the no attempt group (Figure 1b). Consistent with these observations, mean suicide ideation severity did not differentiate suicide attempt groups (F(1,23)=0.91, p=.351). In addition, change slopes did not differ between suicide attempt groups at either the group (F(1,56)=2.01, p=.162) or individual (F(1,322)=0.03, p=.857) level. These results indicate that neither severity of suicide ideation nor rate of decline in suicide ideation differentiated participants who attempted suicide from those who did not.

Figure 1.

Session-to-session change in mean suicide ideation severity (a) and mean person-centered suicide ideation severity (b) during the course of brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (BCBT) among 33 active duty U.S. Soldiers with one prior suicide attempt who either made a suicide attempt during follow-up (dashed line) or did not attempt suicide during follow-up (solid line).

Results of dynamical systems models

Results of the dynamical systems models are summarized in Table 1. In both models, BDI9t was statistically significant and negative in value. This indicates that, at both the group and individual levels, suicide ideation was attracted towards a stable set point, such that when suicide ideation during the current session was more severe (i.e., higher) than this set point, it tended to decrease at the next session. Conversely, when suicide ideation during the current session was less severe (i.e., lower) than this set point, it tended to increase at the next session. Suicide ideation therefore demonstrated stability over the course of treatment at both the group and the individual levels. In the variable-centered model, the three-way interaction was not statistically significant but the two-way interaction of BDI9t and session number was statistically significant, which indicated the suicide ideation became more resistant to change over the course of treatment. In the person-centered model, the three-way interaction was statistically significant, indicating that suicide ideation’s resistence to change over the course of treatment differed between those who subsequently attempted suicide and those who did not.

Table 1.

Results of variable-centered (i.e., between person) and person-centered (i.e., within person) dynamical systems growth models predicting session-to-session change in suicide ideation severity among 33 active duty U.S. soldiers with a previous history of suicide attempt

| Predictor of Change in BDI9 | Variable-Centered | Person-Centered |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | 0.36 (0.07)*** | 0.07 (0.04) |

| Session No. | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.01) |

| BDI9t | −0.71 (0.07)*** | −0.84 (0.07)*** |

| Attempt | 0.19 (0.21) | 0.02 (0.11) |

| Attempt × Session No. | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| BDI9t × Session No. | −0.02 (0.01)* | −0.02 (0.01)* |

| BDI9t × Attempt | −0.07 (0.21) | −0.21 (0.23) |

| BDI9t × Attempt × Session No. | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.03)* |

| Random Effects | ||

| Residual | 0.14 (0.01)*** | 0.14 (0.01)*** |

| Intercept | 0.18 (0.06)** | 0.04 (0.02)** |

| BDI9t | 0.09 (0.03)** | 0.10 (0.04)** |

| Session No. | 0.002 (0.001)** | -- |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001;

BDI9=Beck Depression Inventory Item 9 score.

To facilitate the interpretation of person-centered effects, we decomposed the interaction term by suicide attempt group (see Table 2). These results indicate several important differences. First, the person-centered BDI9t coefficient was significantly larger in magnitude in the suicide attempt group. Second, the two-way interaction of person-centered BDI9t and session number was statistically significant in the suicide attempt group but not in the no attempt group. In combination, these findings indicate that, among participants who subsequently made a suicide attempt, suicide ideation was more resistant to change at the outset of treatment and remained resistant to change over the course of treatment. In addition, variability in suicide ideation remained relatively constant. Among participants who did not make a suicide attempt, however, suicide ideation was less resistant to change at the outset of treatment but became increasingly resistant to change as treatment progressed, and variability in suicide ideation reduced in magnitude. As can be seen in Figure 1b, participants who made a suicide attempt during follow-up showed larger fluctuations in suicide ideation than participants who did not.

Table 2.

Differences in within-person regression coefficients among participants, by occurrence of suicide attempt during follow-up

| Predictor of Change in Suicide Ideation | Attempt | No Attempt |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.04) |

| Session No. | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.01)*** |

| BDI9t | −1.05 (0.22)*** | −0.84 (0.07)*** |

| BDI9t × Session No. | 0.04 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.01)* |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001;

BDI9=Beck Depression Inventory Item 9 score.

Discussion

Among treatment-seeking military personnel who started treatment with one prior suicide attempt, neither between-person nor within-person severity of suicide ideation differentiated those who eventually made a second suicide attempt and those who did not. Between-person change patterns likewise failed to distinguish the recurrence of suicidal behavior. In contrast, several within-person change patterns were significantly associated with the recurrence of suicidal behavior. Among participants who attempted suicide, within-person suicide ideation demonstrated greater resistance to change and larger within-person fluctuations over the entire course of treatment. Among participants who did not attempt suicide, however, within-person suicide ideation was less resistant to change at the start of treatment, became increasingly resistant to change over time, and showed much smaller fluctuations. Taken together, these findings suggest that change processes in suicide ideation did not differ between patients who made a second suicide attempt and those who did not, but certain change processes within patients were associated with the recurrence of suicidal behavior.

This pattern converges with an accumulation of research suggesting that within-person variability explains a larger amount of change in suicide ideation than between-person variability (Bagge, Littlefield, Conner, Schumacher, & Lee, 2014; Kleiman et al., 2017; Millner et al., 2017). A history of multiple suicide attempts has also been found to be associated with significantly increased variability in suicide ideation (Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Witte et al., 2005). Relatedly, EMA research suggests that variability in suicide ideation among individuals with recurrent suicidal behavior tends to be most pronounced among individuals who report a greater number of lifetime suicide attempts (Kleinman et al., 2018). Finally, frequency of suicidal thoughts has been shown to have a stronger prospective association with increased risk of a suicide attempt than the severity and duration of suicidal thoughts (Miranda, Ortin, Scott, & Shaffer, 2014). The present study builds upon these findings in several ways. First, our use of repeated assessments over multiple time points in study provides a more nuanced understanding of the association between fluctuations in suicide and later suicidal behaviors than previous studies. Miranda and colleagues, for example, retrospectively assessed frequency, severity, and duration of suicide ideation at a single time point only. Second, we used both variable-centered and person-centered analyses to consider both between- and within-person associations with recurrent suicidal behavior. Previous studies have used only one of the two modeling approaches: either variable-centered (Bryan & Rudd, 2016; Witte et al., 2005) or person-centered (Kleinman et al., 2018).

From a more practical perspective, the present results suggest that recurrent suicidal behavior may be associated with suicide ideation that is highly variable. Of note, the observed coefficient value for BDI9t as a predictor of change in suicide ideation was −1.05 (see Table 2). In dynamical systems models, coefficient values that exceed −1 characterize systems that “overcorrect” or “overshoot its mark” when attempting to reestablish homeostatic balance. The result of this change process is marked vacillations between competing states. Participants who eventually made a second suicide attempt therefore showed a reduction in mean suicide ideation severity, but this trend was characterized by marked fluctuations suggesting a rapid switching back and forth beween high risk and low risk states (see Figure 1b). Vulnerability for switching to a high risk state therefore persisted in this subgroup of patients despite an overall reduction in suicide ideation over the course of treatment. This switching back and forth between high risk speaks to the stable or “chronic” aspects of suicide risk articulated by the fluid vulnerability theory (Rudd, 2006), and aligns with previous findings that individuals with a history of multiple suicide attempts show switch back and forth suddenly between low risk states and a high risk states (Bryan & Rudd, 2017).

In contrast to this change process among participants who made a second suicide attempt, the change process associated with the absence of follow-up suicide attempts was smoother and more gradual. This process was facilitated by the fact that suicide ideation was less resitent to change at the beginning of treatment, such that initial declines in suicide ideation severity were not counteracted by a competing force seeking to preserve or maintain a high risk state. As participants shifted to lower risk states, suicide ideation’s resistence to change increased, effectively decreasing the likelihood that a patient would switch back to a high risk state.

From a clinical perspective, our results therefore suggest that the severity of suicide ideation at any given time point may have only limited clinical utility for determining which patients are most likely to engage in recurrent suicidal behavior. This is likely due in part to the nonlinear and dynamic nature of suicide risk combined with the emergent nature of suicidal behaviors, both of which are primarily characterized by within-person versus between-person change processes. Considering session-to-session change processes within patients over the course of treatment may therefore provide a better alternative. Further research is needed to further understand how temporal change processes might signal the emergence of recurrent suicidal behavior and how such change processes might be used practically within clinical settings.

The present results also hold a number of implications for research. Specifically, traditional methods for determining treatment effectiveness, which typically compare mean suicide ideation scores between treatment groups and assume linear change processes may not accurately capture a treatment’s effect. This might explain why empirically-supported treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention and dialectical behavior therapy, both of which outperform comparison treatments with respect to reducing suicidal behaviors, generally demonstrate equivalence with respect to mean suicide ideation scores (e.g., Brown et al., 2005; Linehan et al., 2006; Rudd et al., 2015). Person-centered nonlinear dynamic models may provide better information than variable-centered linear models for understanding treatment effectiveness.

Overall, our results suggest that increased variability in suicide ideation may serve as a vulnerability for recurrent suicidal behavior, and support the fluid vulnerability theory’s conceptualization of suicidal behavior as an emergent phenomenon associated with nonlinear dynamic change processes within individuals over time (Rudd, 2006; Bryan & Rudd, 2016). To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine how patterns of change in suicide ideation, repeatedly assessed over the course of multiple weeks, is associated with the emergence of recurrent suicidal behaviors among first-time suicide attempters. As such, additional research with larger samples and a sufficient number of measurements both before and after the occurrence of a repeat suicide attempt is needed to further test this possibility.

Conclusions based on the present study should also be made with consideration for several limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small, being comprised of only 33 patients, of whom only six made a suicide attempt during follow-up. Although the high volume of repeated assessments provided sufficient power to detect meaningful differences in temporal patterns, our results should be considered preliminary until replicated in larger samples. Second, our sample was comprised of active duty U.S. Soldiers only, which may limit generalizability to other populations and settings. Third, data were collected from patients engaged in outpatient brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention, with appointments occurring approximately once per week. Different patterns may exist among patients receiving other types of treatment and/or receiving care in other clinical settings (e.g., inpatient units). Relatedly, different patterns may be evident when using different assessment schedules. Assessing suicide ideation during briefer timeframes akin to those used in daily diary studies and EMA studies (e.g., every few hours), for example, may reveal different change processes. Fourth, our limited sample size restricted our ability to consider how change processes before and after the suicide attempt might differ (or not). Some evidence suggests, for example, that change processes associated with the emergence of suicidal behavior become more pronounced in the time leading up to the behavior (Bryan et al., 2017).

Finally, our method for assessing suicide ideation used only a single item and focused only on severity of suicide ideation and suicidal intent; other dimensions of suicidal thinking such as planning and perceived controllability of one’s thoughts were not considered. Although this approach is limited with respect to potential measurement error and problems of misclassification (Millner et al., 2017), single-item assessment methods are common in clinical practice owing to its efficiency and validity relative to longer scales (Desseilles et al., 2012). The approach is therefore recommended for standard care of suicidal patients (NAASP, 2018), and generalizability to clinical settings is high. Future research should nonetheless consider how multiple aspects of suicidal thinking might be associated with the emergence of recurrent suicidal behaviors. Despite these limitations, the present study suggests that consideration of nonlinear dynamics in suicide ideation may lead to improved identification of patients who are vulnerable to making repeat suicide attempts, and could provide valuable information regarding treatment response among high risk patients.

Funding Sources

This study was supported in part by research funding by the Department of Defense (Award No. W81XWH-09-1-0569; PI: Rudd), the National Institute of Mental Health (Award No. 1R01MH117600-01; PI: Bryan), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Award No. UL1TR002538 and KL2TR002539; PI: Rozek). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the position, policy, or official views of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, the Department of the Army, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

C. J. Bryan reports grant funding from the Department of Defense, the Department of the Air Force, the Bob Woodruff Foundation, and the Boeing Company, and consulting fees from Neurostat Analytical Solutions, Northrop Grumman Technical Services, and Oui Therapeutics. M. D. Rudd, D. C. Rozek, and J. Butner report grant funding from the Department of Defense. M. D. Rudd also reports consulting fees from Oui Therapeutics.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2003). Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias SA, Miller I, Camargo CA Jr, Sullivan AF, Goldstein AB, Allen MH, … & Boudreaux ED (2015). Factors associated with suicide outcomes 12 months after screening positive for suicide risk in the emergency department. Psychiatric Services, 67, 206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Littlefield AK, Conner KR, Schumacher JA, & Lee HJ (2014). Near-term predictors of the intensity of suicidal ideation: An examination of the 24 h prior to a recent suicide attempt. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bänziger T, Patel S, & Scherer KR (2014). The role of perceived voice and speech characteristics in vocal emotion communication. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 38, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, & Rothstein HR (2011). Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rozek DC (2018). Suicide prevention in the military: a mechanistic perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2006). Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 185–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2015). Demographic and diagnostic differences among suicide ideators, single attempters, and multiple attempters among military personnel and veterans receiving outpatient mental health care. Military Behavioral Health, 3, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2016). The importance of temporal dynamics in the transition from suicidal thought to behavior. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Butner JE, Sinclair S, Bryan ABO, Hesse CM, & Rose AE (2017). Predictors of emerging suicide death among military personnel on social media networks. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 413–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Leeson B, & Rudd MD (2015). Acute vs. chronic stressors, multiple suicide attempts, and persistent suicide ideation in US soldiers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203, 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Johnson LG, David Rudd M, & Joiner TE (2008). Hypomanic symptoms among first‐time suicide attempters predict future multiple attempt status. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, & Rudd MD (2017). Nonlinear change processes during psychotherapy characterize patients who have made multiple suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. Available online at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sltb.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner JE, Gagnon KT, Geuss MN, Lessard DA, & Story TN (2015). Utilizing topology to generate and test theories of change. Psychological Methods, 20, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SM, Ram N, Boker SM, Fujita F, & Clore G (2005). Emotion as a thermostat: representing emotion regulation using a damped oscillator model. Emotion, 5, 208–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense (2015). VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Desseilles M, Perroud N, Guillaume S, Jaussent I, Genty C, Malafosse A, & Courtet P (2012). Is it valid to measure suicidal ideation by depression rating scales? Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, … & Nock MK (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KL, Brown GK, Jager-Hyman S, Cha J, Steer RA, & Beck AT (2015). The Predictive Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory Suicide Item. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76, 1683–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, & King CA (2015). Predicting future suicide attempts among adolescent and emerging adult psychiatric emergency patients. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr, & Rudd MD (2000). Intensity and duration of suicidal crises vary as a function of previous suicide attempts and negative life events. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, & Nock MK (2018). Real-time assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Turner BJ, Fedor S, Beale EE, Huffman JC, & Nock MK (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 726–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, & Wagner A (2006). Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment, 18, 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, & Nock MK (2017). Describing and measuring the pathway to suicide attempts: A preliminary study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47, 353–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Ortin A, Scott M, & Shaffer D (2014). Characteristics of suicidal ideation that predict the transition to future suicide attempts in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1288–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara BL (1996). A dynamic developmental model of suicide. Human Development, 39, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (2018). Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe. Washington, DC: Education Development Center, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Millner AJ, Joiner TE, Gutierrez PM, Han G, Hwang I, …, & Kessler RC (2018). Risk factors for the transition from suicide ideation to suicide attempt: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Joural of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, … & Mann JJ (2011). The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JR (2003). The anatomy of suicidology: A psychological science perspective on the status of suicide research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD (2006). Fluid vulnerability theory: a cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic suicide risk In Ellis TE (Ed.), Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy (pp. 355–368). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Bryan CJ, Wertenberger EG, Peterson AL, Young-McCaughan S, Mintz J, … & Wilkinson E (2015). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Joiner T, & Rajad MH (1996). Relationships among suicide ideators, attempters, and multiple attempters in a young-adult sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiepek G, Fartacek C, Sturm J, Kralovec K, Fartacek R, & Plöderl M (2011). Nonlinear dynamics: theoretical perspectives and application to suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41, 661–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, & Ludman EJ (2013). Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatric Services, 64, 1195–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission (2016). Sentinel Event Alert 56: Detecting and Treating Suicide Ideation in All Settings. Available online at https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_56_Suicide.pdf [PubMed]

- Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Joiner TE, & Schmidt NB (2005). Variability in suicidal ideation: a better predictor of suicide attempts than intensity or duration of ideation? Journal of Affective Disorders, 88, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Holm-Denoma JM, Zuromski KL, Gauthier JM, & Ruscio J (2017). Individuals at high risk for suicide are categorically distinct from those at low risk. Psychological Assessment, 29, 382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyder M, & De Leo D (2007). Behind impulsive suicide attempts: Indications from a community study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 104, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]